Castration of calves

Learn the reasons for castration and proper processes.

ISSN 1198-712X, Published June 2007

Castration defined

Castration of a bull (male) calf is the process of removal or destruction of the testicles. A steer is a castrated male calf raised for beef.

Reasons for castration

Reasons given for castrating beef calves include to:

- stop the production of male hormones and semen

- historically, tame oxen for draught purposes

- prevent mating and reproduction after the age of puberty

- produce docile cattle that are easier to handle compared to bulls

- decrease aggressiveness, mounting activity, injuries, frequency of dark-cutting carcasses

- enhance on-farm safety for animals, producers and employees

- decrease costs associated with fencing and handling facilities compared to bulls

- avoid discounted price that packers pay for bull carcasses

- provide meat products of the quality consumers demand

Managing male calves

Owners may choose to manage male calves as intact bulls, castrate early, castrate late, or castrate plus implant with a growth stimulant implant. Which is selected will depend on the available handling facilities, the producer's ability, the awareness of castration effects and the market available for the calves. Owners with guaranteed buyers willing to purchase green calves (horns and testicles in place), at the same price as processed calves (castrated and dehorned), might be advised to avoid these procedures. However, this buyer is very rare. Most purchasers of green calves are well aware of the risks associated with processing older calves and routinely bid less at auction. Recently, preconditioned (castrated, dehorned, vaccinated, bunk-adjusted) calves have brought a premium price at auctions.

Beef from intact bulls

There is a niche market for meat from young, intact bulls. The meat appeals to consumers who oppose castration for welfare reasons, desire meat produced without hormonal implants and prefer lean meat. Intact animals could be marketed one to two months earlier than castrates, which saves feed. Generally, consumers cannot detect differences in taste or tenderness between meat from steers and young bulls.

Immunization as an alternative to castration

Researchers have shown immunization/vaccination techniques will suppress male hormone production, reduce testicular development and result in steer-like carcasses. Growth and carcass characteristics of the immunized animals are similar to steers. Researchers also have found that castration by immunization reduces aggressive behavior and is an effective alternative to surgical castration to manage bulls. However, there is no commercial product available for use. The need for repeated injections likely would discourage its adoption.

Castration age

Castration at a young age minimizes hazards to the calf, the cow-calf producer and the feedlot owner. Hazards for calves and owners include:

- sickness or death of calves following castration at an older age

- decreased liveweight gains (productivity) in the weeks following castration of older calves

Many producers choose to castrate new-born calves because:

- techniques are easier for the operator

- castration is less stressful on newborn calves

- concerns for animal welfare related to castrating older calves

Although there is no evidence that pain differs between young and older calves, there is less risk with castration of young calves.

Testosterone effect

Some producers delay castration to take advantage of the growth effects of the male hormone testosterone. Testosterone secretion commences between 3.5 and 5.5 months. The differences in liveweight gain of castrates and bulls are first apparent at four to five months.

Liveweight gains

Studies of the effects of castration on liveweight gains have been reported from many countries. In general, there are no differences in liveweight gains for bulls and steers in the 21 days following castration at one month of age. However, there are significant differences with castration at older ages. During the 1980s and early 1990s, research focused on methods to recover weight lost by use of hormonal implants. In the past decade or so, research seems to focus on alleviation of pain and animal welfare issues associated with castration.

Choice of castration methods

Castration may be accomplished by physical, chemical or hormonal techniques. Physical methods are most common. Testicles may be removed surgically or killed by obstructing the blood supply. Young calves may be castrated with rubber rings, Burdizzo or by surgery. Surgical castration may be more appropriate for calves that are not handled until weaning.

Elastic band castration

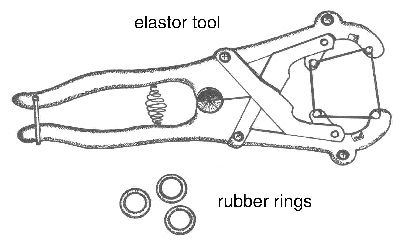

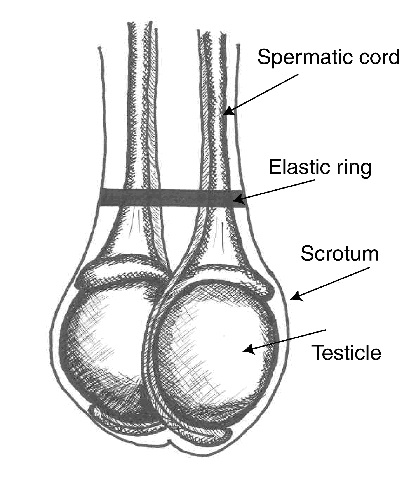

Elastic band castration cuts off blood supply to the testicles. A lack of blood supply kills the testicles. The equipment for banding calves less than three weeks of age is called an elastrator. An elastrator (Figure 1) is the tool used to apply an elastic band to the neck of the scrotum. The elastic band obstructs blood flow to the testicles and the scrotum. In time, the scrotum and testicles fall from the body. The elastrator band is most reliable for calves less than three weeks of age. EZE and Callicrate are tools used to band older, larger calves with latex bands. Vaccination to protect against tetanus and blackleg is recommended. These infections may be more common when older calves are banded. Vaccines must be given weeks in advance of banding. Researchers from Saskatchewan provide strong evidence against using elastic band or surgical castration of mature bulls based on pain response, time to heal and post-castration weight loss. Researchers from Alberta found no advantage in average daily gain with late castration with latex bands vs. surgical castration.

Faulty application of elastic bands results in retention of a testicle and calves with a bull-like appearance (stags). To successfully use elastic bands, the operator must understand the anatomy and restrain the calf properly. Some European countries have banned elastic band castration because officials consider it inhumane.

Technique

- Use the elastrator technique for calves from birth to three weeks of age.

- Use elastic rings purchased within the last 12 months to avoid breakage and assure a tight fit. The rings must be strong enough to cut off blood flow in the arteries as well as the veins. If not, the scrotum will swell.

- Pull both testicles into the scrotum. A muscle attached to each testicle will be pulling against you.

- Place the rubber band on the elastrator. Hold the elastrator with the prongs facing up. Close the handles to open the band.

- With the calf standing and both testicles in the scrotum, stretch the ring open and slip the open band up over the scrotum. Release the band just above the top of the testicles (~0.5 cm), not at the base of the scrotum.

- Check to be sure both testicles are still in the tip of the scrotum and that the ring is placed properly (Figure 2). If not, cut the ring with scissors and start again.

- Remove the elastrator from under the band.

- EZE or Callicrate bands are applied in a similar location. See the manufacturer's literature for detailed instructions.

Pain:

- local anaesthesia virtually eliminates the acute pain caused by rubber-ring or latex-band castration

- acute pain caused by banding is greater than that caused by

- Burdizzo clamps

Advantages and disadvantages:

- bloodless, easy to perform

- large lesions may form above the band site and persist for long times, making latex bands inappropriate for yearling cattle

- wounds heal more slowly than those from surgical castration

- newest versions of banders for older calves adjust the latex bands to correct tension

- potential for missed testicles

- band may break or band may not disrupt all circulation to the testicles

- preferred for castrating at a wet, muddy feedlot

- infections, including tetanus and blackleg, may warrant vaccination prior to banding

- public concern about pain and animal welfare associated with banding older calves

- lower weight gains following latex-band castration compared to surgical castration

- EZE and Callicrate methods without anaesthesia for older bulls deemed inhumane and unethical

Burdizzo clamps for castration

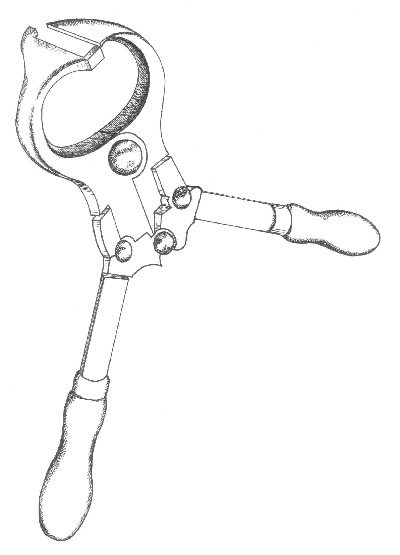

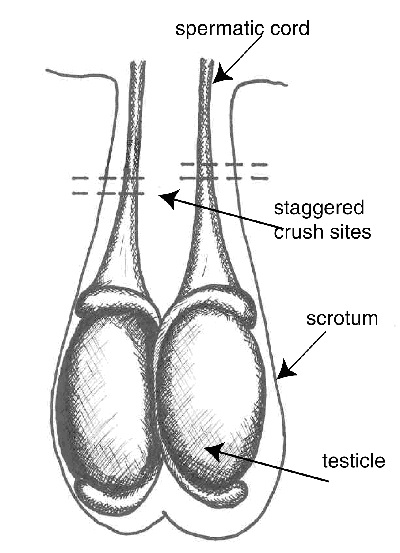

The Burdizzo method crushes the blood vessels, interrupts the blood supply to the testicle and thus kills the testicle. Good restraint is essential because the Burdizzo must be in place about 10 seconds to crush the artery.

The Burdizzo (Figure 3) must be in good condition. The jaws must be parallel and close uniformly across their width so pressure will be evenly distributed across their length. Leave the Burdizzo slightly open when not in use.

Technique

- Use this technique when the spermatic cord can be palpated — one month and older.

- Choose and use the proper sized forceps for the size of animal. With undersized forceps, there will be too much tissue between the jaws and there will not be enough force to properly crush the arteries.

- Find the spermatic cord on one side of the scrotum. Reach between the hind legs and grasp the scrotum above the testicles. The spermatic cord runs from the testicle into the calf's body. It is about the size of a pencil and moves easily from side to side in its half of the scrotum. Pinch the cord to the outside edge of the scrotum between your thumb and forefinger. If right handed, use your left hand to hold the cord and your right to operate the Burdizzo.

- Position the Burdizzo correctly for crushing. One jaw of the Burdizzo has projections at each end to keep the spermatic cord from slipping out of the Burdizzo. Place the jaw with the projections on the front side of the scrotum. Point the projections toward you.

- Include only the part of the scrotum that contains the spermatic cord between the jaws of the Burdizzo. Do not crush more of the scrotum than necessary. The jaws should be placed just above (1-1.5 cm) the top of the testicle.

- Close the Burdizzo, count out 10 seconds and check to be sure the spermatic cord has been held between the jaws of the Burdizzo. You can also rock the spermatic cord back and forth in the jaws.

- Release the Burdizzo, move it to a new site 1 cm below your first site, and repeat steps four and five. Choose a site below the first crush to minimize acute pain from a second crush.

- Repeat the procedure on the opposite side. Stagger the pinched areas on the left and right side of the scrotum. Do not pinch a part of the scrotum that lines up with a pinch on the opposite side. The crush lines must not overlap the centre-line of the scrotum (Figure 4).

- Check calves four to six weeks later to be sure the testicles have shriveled. The testicles swell initially and then degenerate and shrink in size.

Pain:

- local anaesthesia plus a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug are needed to eliminate acute pain caused by Burdizzo castration

- acute pain caused by Burdizzo clamps is less than that caused by surgical, rubber-ring or latex-band castration

Advantages and disadvantages:

- bloodless

- slow to perform and requires expertise

- unreliable when done incorrectly, leads to stags

- equipment becomes ineffective after long-term use and must be replaced

- less reduction in weight gain after castration compared to surgical or latex-band

Surgical castration

Surgical castration is the most certain method of castration because the testicles are removed completely. It is best performed before or after fly season and when calves can be turned into a dry area after the surgery. Surgical castration can be performed on any age calf. It is easier to learn on calves with larger testicles. However, larger and older calves experience more stress and usually bleed more than younger calves.

Good restraint is essential to minimize the risk to calves and operators.

Instruments for surgical castration include the Newberry knife, scalpel (Figure 5) and emasculator.

Technique

- Wash and clean your hands and surgical equipment using an antiseptic solution. Position yourself at the side or rear of the calf and reach forward between the hind legs.

- Make sure the scrotum is clean. You may use a mild surface disinfectant (such as iodine) to prepare the incision sites.

- Make an incision to open the skin of the scrotum using Method A or B.

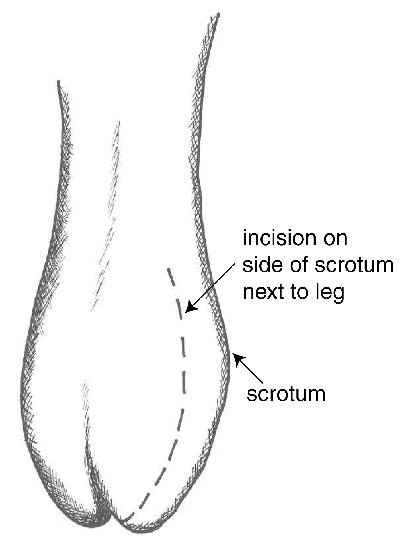

Incision method A

- Make the incisions on the outside of the lower half of each side of the scrotum (Figure 6).

- If you are right handed, use your left hand to force one testicle to the bottom outside of the scrotum. Once the testicle is in the proper site, hold it there and use a scalpel to make a generous incision over the testicle. The incision may extend into the testicle itself.

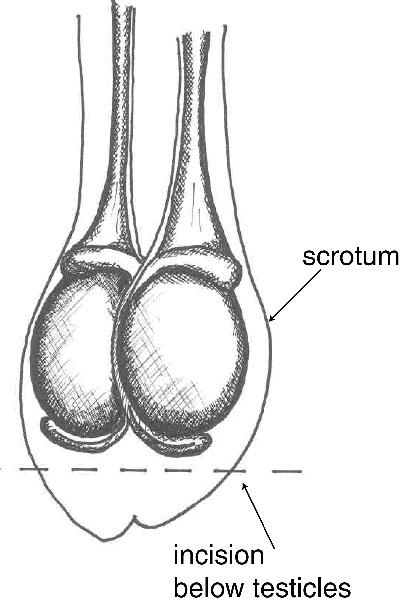

Incision method B

- Use one incision to remove the bottom third of the scrotum. To do this, first push the testicles up toward the body so the lower third of the scrotum is empty.

- Grasp the tip of the scrotum between your thumb and forefinger. Use a sharp scalpel to cut across the scrotum just above your thumb and finger. This cut will completely remove the tip of the scrotum and the testicles will fall down or can be pulled down by reaching up into the open scrotum (Figure 7).

- After making the incision, the remainder of the castration is similar.

- Pull the testicle through the incision. It will be covered with a thin, but tough, white membrane. Separate this from the testicle by pulling it away near the tip of the testicle.

- The remaining tough cord contains the artery, veins and spermatic cord.

- In older calves, use an emasculator (Figure 8) to crush and cut both blood vessels and spermatic cord at the same time. An emasculator lessens the risk of bleeding. (The emasculator must be placed on the cord correctly in order to crush the cord properly).

- In younger calves (<3 months), it is common to separate the blood vessels from the vas deferens. Shave through the vas with the scalpel. Gently pull the vessels until the strand breaks.

- Repeat on the other side.

There should not be any tissue hanging from the scrotum once the castration is complete.

If using incision Method B, the castration is complete. If using Method A, once both testicles have been removed, make an incision completely through the bottom half of the median septum to ensure good drainage.

Pain:

- local anaesthesia plus a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug eliminate acute pain caused by surgical castration

- acute pain caused by surgical castration is greater than that caused by Burdizzo clamps

Advantages and disadvantages:

- not bloodless, bleeding is a risk

- sure castration because the testicles are removed

- more time to perform than banding

- risk of infections because of open wounds

- not recommended for castrating bull calves at a feedlot with wet, muddy conditions

- greater reduction in weight gain after castration compared to Burdizzo

- surgical wounds heal more quickly than those from rubber ring

- risk of injury to the surgeon

Aftercare

- Provide a clean, dry environment for calves after castration.

- Inspect the cattle closely for two weeks after castration. With latex bands, the scrotum should drop off within seven weeks after castration.

- Look for swelling, signs of infection, tetanus and abnormal gait.

- Treat wounds as needed.

- Get professional help when calves show swelling, severe pain or infection.

Welfare significance

- Physical castration causes pain and side effects.

- Young calves recover quicker and have fewer complications than older calves.

- Acute pain caused by Burdizzo methods is less than that caused by surgical, rubber-ring or latex-band castration.

- There is no evidence to show young calves experience less pain than older calves.

- Local anaesthesia eliminates acute pain caused by rubber-ring or latex-band castration.

- Local anaesthesia combined with a systemic analgesic, such as the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug ketoprofen, eliminates pain caused by Burdizzo or surgical castration.

- Ketoprofen alone may not eliminate pain-induced behaviour seen during the castration process.

- Castration of older males without anaesthesia is deemed inhumane and unethical.

- Use of pain relief is an additional cost for producers. Pain relief may be limited by the availability of drugs for farmers to use and the scarcity of veterinarians in farm animal practice.

- In Ontario, auxiliaries employed by veterinarians may administer local nerve blocks and castrate cattle less than two months of age while under immediate, direct or indirect supervision of a veterinarian. They may castrate cattle greater than two months of age when under immediate or direct supervision.

Anaesthesia and pain Relief

Choices in anaethesia and pain relief include:

- short-acting, local anaesthetic (e.g. lidocaine) with an effect for about 45-90 minutes

- an epidural injection designed to block pain in the hind quarters and testicular region

- local injections into the testicles, incision site or spermatic cord

- alpha-2 agonist (xylazine) given alone or in conjunction with a local anaesthetic will provide analgesia for a few hours

- non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) such as ketoprofen used alone, with local anaesthetics or with xylazine

Acknowledgement

Gerrit Rietveld, Animal Care Specialist, OMAFRA, drew the diagrams for this publication.

References

- Adams TE, Adams BM. Feedlot performance of steers and bulls actively immunized against gonadotropin-releasing hormone. J Anim Sci. 1992;70(6):1691-1698.

- Bagu ET, Madgwick S, Duggavathi R, et al. Effects of treatment with LH or FSH from 4 to 8 weeks of age on the attainment of puberty in bull calves. Theriogenology. 2004;62(5):861-73.

- Baker JF, Strickland JE, Vann RC. Effect of castration on weight gain of beef calves. Bovine Practitioner. 2000;34(2):124-6.

- Berry BA, Choat WT, Gill DR, Krehbiel CR, Smith RA, Ball RL. Effect of Castration on Health and Performance of Newly Received Stressed Feedlot Calves. Oklahoma Agricultural Experiment Station Report 2001.

- Bonneau M, Enright WJ. Immunocastration in cattle and pigs. Livestock Production Sci. 1995;42(2-3):193-200.

- Brannang E. The effect of castration and age of castration on the growth rate, feed conversion and carcass traits of Swedish Red and White Cattle. Part I. Studies on monozygous cattle twins XVIII. Lantbrukshogskolans Annaler. 1966;32:1-90.

- Burciaga-Robles, LO, Step, DL, Holland, BP, McCurdy, MP, Krehbiel, CR. Effect of castration upon arrival on health and performance of high risk calves during a 44 day receiving period. The AABP Proceedings. 2006;39:234-235.

- Capucille DJ, Poore MH, Rogers GM. Castration in cattle: techniques and animal welfare issues. Compend Cont Educ Pract Veterinarian. 2002;24(9):66-73.

- Cohen RDH, Hunter PSW, Janzen ED, et al. The effect of time and method of castration and Ralgro implants on male calves. Termuende Research Station: Management, Production and Research. 1985:1-42.

- D'Occhio MJ, Aspden WJ, Trigg TE. Sustained testicular atrophy in bulls actively immunized against GnRH: potential to control carcass characteristics. Anim Reprod Sci. 2001;66(1-2):47-58.

- Earley B, Crowe MA. Effects of ketoprofen alone or in combination with local anesthesia during the castration of bull calves on plasma cortisol, immunological, and inflammatory responses. J Anim Sci. 2002;80(4):1044-1052.

- Fisher AD, Crowe MA, delaVarga MEA, Enright WJ. Effect of castration method and the provision of local anesthesia on plasma cortisol, scrotal circumference, growth, and feed intake of bull calves. J Anim Sci. 1996;74(10):2336-2343.

- Fisher AD, Knight TW, Cosgrove GP, et al. Effects of surgical or banding castration on stress responses and behaviour of bulls. Aust Vet J. 2001;79(4):279-84.

- Heaton K, Zobell DR. A successful collaborative research project: Determining the effects of delayed castration on beef cattle production and carcass traits and consumer acceptability. J of Extension. 2006;44 (2).

- Knight TW, Cosgrove GP, Death AF, Anderson CB. Effect of age of pre- and post-pubertal castration of bulls on growth rates and carcass quality. N.Z. J Agric Res. 2000;43:585-8.

- Knight TW, Cosgrove GP, Death AF, Anderson CB. Effect of method of castrating bulls on their growth rate and liveweight. N.Z. J Agric Res . 2000;43(2):187-192.

- Lindner HR, Mann T. Relationship between the content of androgenic steroids in the testes and the secretory activity of the seminal vesicles in the bull. J Endocrinol. 1960;21:341-360.

- Madgwick S, Bagu ET, Duggavathi R, et al. Effects of treatment with GnRH from 4 to 8 weeks of age on the attainment of sexual maturity in bull calves. Anim Reprod Sci. 2007;in press.

Molony V, Kent JE, Robertson IS. Assessment of acute and chronic pain after different methods of castration of calves. Appl Anim Behaviour Sci. 1995;46(1):33-48. - O'Connor B, Leavitt S, Parker K. Tetanus in feeder calves associated with elastic castration. Can Vet J. 1993;34:311-312.

- Petherick JC. Animal welfare provision for land-based livestock industries in Australia. Aust Vet J. 2006;84:379-383.

- Price E O, Adams TE, Huxsoll CC, Borgwardt RE. Aggressive behavior is reduced in bulls actively immunized against gonadotropin-releasing hormone. J Anim Sci. 2003;81:411-415.

- Rollin BE. An ethicist's commentary on the elastrator for older bulls. Can Vet J. 2003;44(8):624.

- Stafford KJ, Mellor DJ. The welfare significance of the castration of cattle: a review. N.Z. Vet J. 2005;53(5):271-8.

- Stafford KJ, Mellor DJ, Dooley AE, Smeaton D, McDermott A. The cost of alleviating the pain caused by the castration of beef calves. Proc N.Z. Soc Anim Prod. 2005;65.

- Stookey, J. M. 2001. Castration and dehorning: We have done the science, when will we use the results? Conference Animal Agriculture 2001. Saskatoon, SK Jan. 12.

- Thuer S, Mellema S, Doherr MG, Wechsler B, Nuss K, Steiner A. Effect of local anaesthesia on short- and long-term pain induced by two bloodless castration methods in calves. Vet J. 2007;173(2):333-42.

- Ting STL, Earley B, Hughes JML, Crowe MA. Effect of ketoprofen, lidocaine local anesthesia, and combined xylazine and lidocaine caudal epidural anesthesia during castration of beef cattle on stress responses, immunity, growth, and behavior. J Anim Sci. 2003;81:1281-1293.

- Ting STL, Earley B, Crowe MA. Effect of repeated ketoprofen administration during surgical castration of bulls on cortisol, immunological function, feed intake, growth, and behavior. J Anim Sci. 2003;81:1253-1264.

- Ting STL, Earley B, Veissier I, Gupta S , Crowe MA. Effects of age of Holstein-Friesian calves on plasma cortisol, acute-phase proteins, immunological function, scrotal measurements and growth in response to Burdizzo castration. J Anim Sci. 2005;80(3):377-86.

- Watson M.J. The effects of castration on the growth and meat quality of grazing cattle. Aust J Exp Agr Anim Husb. 1969:164-171.

- Wildman BK, Pollock CM, Schunicht OC, et al. Evaluation of castration technique, pain management, and castration timing in young feedlot bulls in Alberta. The AABP Proceedings. September 2006;39:47-49.

- Zulauf M, Gutzwiller A, Steiner A, Hirsbrunner G. The effect of a pain medication in bloodless castration of male calves on the concentrated feed intake, weight gain and serum cortisol level. Schweiz Arch Tierheilkd. 2003;145(6):283-90