Dairy cow comfort: free-stall dimensions

Learn about the requirements to design comfortable dairy cattle free-stalls. This technical information is for Ontario dairy producers.

Introduction

Cow measurements and their space requirements are important to designing cattle stalls. Cattle require stall dimensions that are appropriate for standing, lying, rising and resting without injury, pain or fear. Stalls must meet the needs of the cow for comfort and the caregiver for cleanliness and ease of cleaning. This document describes cow dimensions, space requirements and stall dimensions for mature Canadian Holstein cows. The concepts shown in Tables 1 and 2 are used to design stalls for Holstein heifers or other dairy breeds.

Choices: stall maintenance/manure system

Choice of manure system and commitment to stall maintenance play an important role in determining stall design. For example, a once-per-day stall cleaning protocol may not be compatible with stall dimensions that focus on comfort of the cow. University of British Columbia (UBC)

Cow dimensions

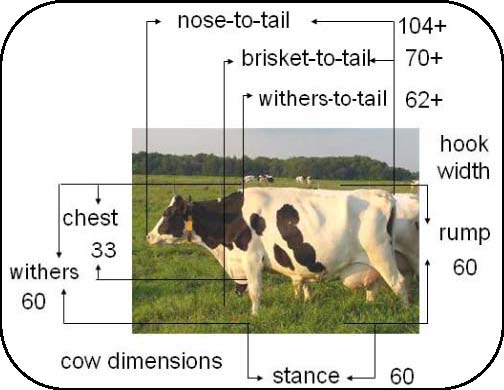

Cows vary in size between and within herds (Figure 1). A barn with one stall size poses several challenges to both management and cows. Stall and cow cleanliness, labor, mastitis, foot diseases and cow comfort are issues to consider in one-group barns. Stalls can be built in three sizes (sized for Lactation 1 heifers, milking cows and dry or special-needs cows) depending on the variation in cow size and their needs within a herd.

The first step in planning stall size is the measurement of Lactation 1 and mature cows in the herd. Rump heights and hook-bone widths are useful measures to estimate several other body dimensions. Since several body dimensions are proportional, ratios provide reasonable estimates of dimensions for calves, heifers or other dairy breeds.

Table 1 shows measurements of mature Canadian Holsteins and some calculated proportions. For example, the cows had a rump height of 152 cm (60 in.), a nose-to-tail length of 2.6 m (8.5 ft) and a hook-bone width of 64 cm (25 in.).

| Body dimension | Measurement cm (in.) | Proportions |

|---|---|---|

|

Nose-to-tail |

Length 259 cm (102 in.) Range 244–279 cm (96–110 in.) |

1.6 x rump height |

|

Imprint length: resting |

183 cm (72 in.) 173–193 cm (68-76 in.) |

1.2 x rump height |

|

Imprint width |

132 cm (52 in.) 122–137 cm (48-54 in.) |

2 x hook-bone width |

|

Forward lunge space |

61 cm (24 in.) |

0.4 x rump height |

|

Stride length when rising |

46 cm (18 in.) |

0.3 x rump height |

|

Rump height: mature |

Median 152 cm (60 in.) Range 147–163 cm (58-64 in.) |

n/a |

|

Rump height: Lactation 1 |

Median 147 cm (58 in.) Top 25% - 150 cm (59 in.) |

n/a |

|

Stance: front-to-rear feet |

152 cm (60 in.) Range 147-163 cm (58-64 in.) |

1.0 x rump height |

|

Withers (shoulder) height |

152 cm (60 in.) Range 147-163 cm (58-64 in.) |

1.0 x rump height |

|

Hook-bone width |

66 cm (26 in.) Range 61-69 cm (24-27 in.) |

n/a |

Space requirements

University of British Columbia research

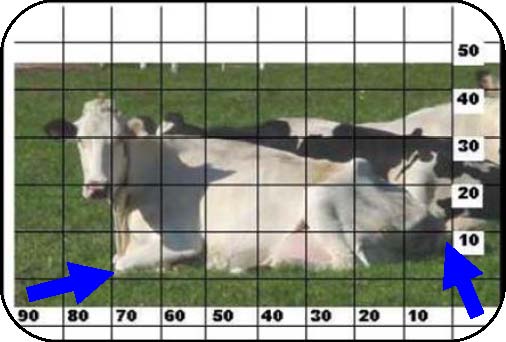

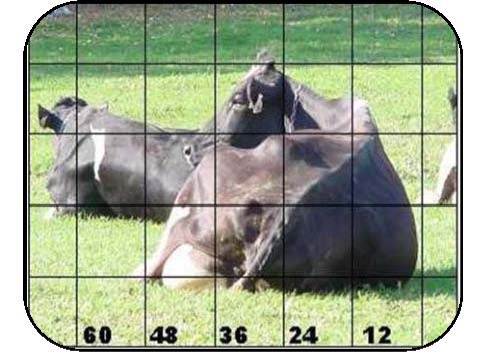

Observations of cows freely lying and rising reveal that a mature Canadian Holstein cow uses 2.6 x 1.32 m (102 x 52 in.) of living space and another 51 cm (20 in.) (41–61 cm (16– 24 in.)) of open forward space for lunging motions. Figures 2 and 3 show several cow dimensions that define this living space.

Nose-to-tail length describes the measurement from the tail to the nose of a cow standing with her head forward. A cow has a normal crook in her neck when lying and her nose-to-tail length is less than while standing.

Imprint length describes the length from folded fore-knee to tail while lying in the narrow position. It defines the bed length needed for resting with all body parts on the stall. Imprint length is greater when the cow extends her front legs forward in normal (long) resting positions (Figure 3).

Imprint width is the lateral distance from the point of the hock on the upper hind leg and the extension of the abdomen on the opposite side when resting in the narrow position (Figure 4). This width is the minimum stall width for a resting cow. For improved comfort, most new free-stall barns are being built with stalls wider than the imprint width of a cow in the narrow resting position.

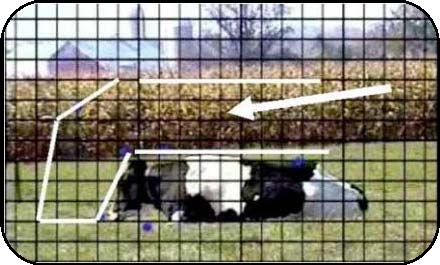

Lunging space is the room needed for lying and rising motions and it extends forward, downward and upward for head lunge and bob, vertically and forward for standing and laterally for hindquarter movements.

Knowledge of the lunging space is essential for properly positioning neck, deterrent straps or bars, solid stall fronts or provision for social space in open-front, head-to-head stalls. A cow's nose uses the space 10–30 cm (4–12 in.) above the surface when lying or rising (Figure 5).

Stall dimensions as ratios of body dimensions

Hook-bone width and rump height are easy to measure and since many body dimensions are proportional these two dimensions are useful references for sizing stalls.

Table 2 shows stall dimensions estimated relationships to body dimensions and example calculations for mature Holsteins in a study herd.

| Stall dimension | Ratio and reference body dimension | Example: a median cow |

|---|---|---|

|

Stall length from curb to solid front |

2.0 x rump height |

2.0 x 152 = 304 cm |

|

Stall length for open front head-to-head |

1.8 x rump height |

1.8 x 152 = 274 cm |

|

Bed length = imprint length |

1.2 x rump height |

1.2 x 152 = 182 cm |

|

Neck-rail height above cow's feet |

0.83 x rump height |

0,83 x 152 = 127 cm |

|

Neck-rail forward location = bed length-2 |

(1.2 x rump height)-2 |

(1.2 x 152) – 5 = 177 cm |

|

Deterrent strap in open-front stalls = 18 ft. |

0.6 x rump height |

0.6 x 152 = 91 cm 0.6 x 60 = 36 in. |

|

Deterrent strap in open-front stalls = 16 ft. |

0.7 x rump height |

0,7 x 152 = 106 cm 0.7 x 60 = 42 in. |

|

Stall width: loops on centres |

2.0 x hook-bone width |

2.0 x 63 = 127 cm 2.0 x 25 = 50 in. |

|

Space between brisket locator and loop |

foot-width |

12 cm (5 in.) |

Neck rail

The neck rail (sometimes called a head rail) is the restraint (often a pipe) mounted to the top or underside of the top pipe of a loop. A neck rail controls the forward location of a cow while standing in the stall. It affects stall standing, perching and stall cleanliness, but not lying. The reference for vertical placement of the neck rail is the standing surface (for example, mattress, mat and bedding) for the cow's feet.

Measure from the concrete platform (or other surface) during construction and allow for the bed. The vertical location above the bed is about 0.8 x rump height. It may be 122 cm (48 in.) for Lactation 1 heifers or 127 cm (50 in.) for mature cows.

The neck rail forward location is a horizontal measurement from the alley curb. It may be 173 cm (68 in.) for Lactation 1 heifers or 178 cm (70 in.) for mature cows.

Considerations for using a neck rail:

- The top pipe of a loop becomes the neck rail when cows lunge through the loop opening.

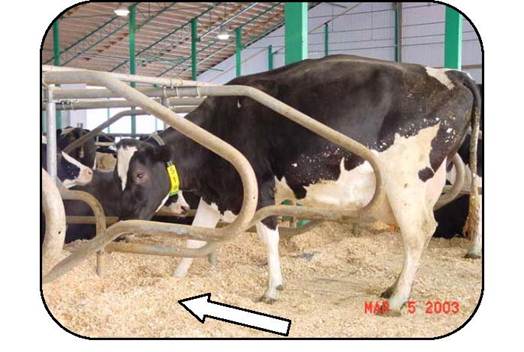

- Proper location of the neck rail lets a cow stand straight with all four feet in the stall and rise without contacting the rail and contributes to stall cleanliness (Figure 6).

- The location is lower and forward of the withers.

- The neck rail is usually directly above or an inch or two to the cow side of the brisket locator.

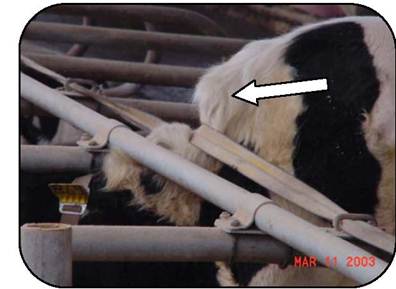

- Perching, diagonal standing or neck injuries may indicate incorrect placement of the neck rail.

- Sole ulcers and lameness occur when neck rails force cows to stand with their front feet on the bed and back feet in the alley (perching in the stall).

- Contact with the neck rail while rising causes injury, pain, fear, frustration and stress and alters stall usage.

- A nylon strap located aft of a neck rail (Figure 7) increases the frequency of perching.

- The distance between neck rails in head-to-head open-front stalls should be equal to or greater than the length from tail to withers of a cow. That is, a cow should be able to stand in the open space. This is possible in 5.5 m (18 ft) head-to-head stalls but not with 4.9–5.2 m (16–17 ft) platforms.

- A neck strap has been used in combination with a brisket rail. Upward flexibility of the nylon strap spares cows from injury. A brisket rail prevents cows from crawling forward (Figure 8).

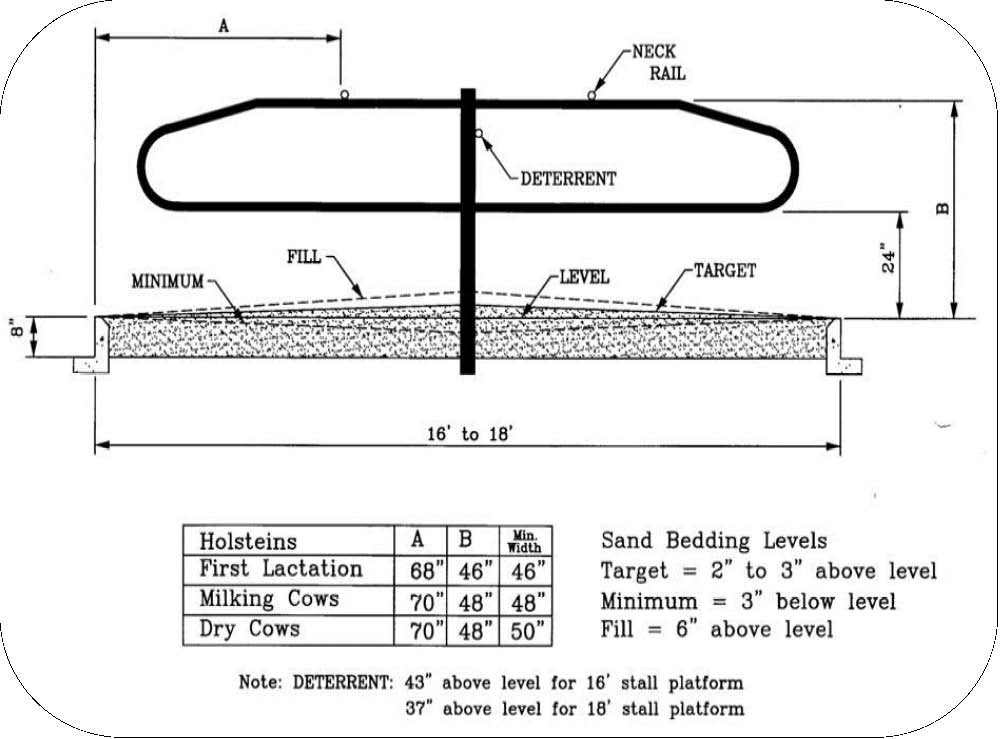

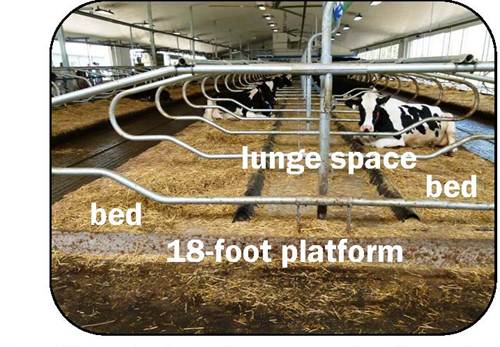

Forward or diagonal lunge

A mature Holstein uses about 3 m (10 ft) of space measured from her tail to the most forward lunge distance when rising or lying normally. Obstructions in the lunging space (for example, a facing cow in short stalls, wall, heap of bedding, concrete curb, post, gate, transverse mounting pipe) lead to diagonal (corner-to-corner) standing, lying and rising.

Considerations for a safe forward or diagonal lunge:

- Provide unobstructed forward space for frontward lunging and bobbing of the head.

- Stalls facing a wall or forward obstruction should be 3 m (10 ft) from alley curb to the wall.

- Platforms for head-to-head stalls should be 5.5 m (18 ft). A cow can use space on the opposite side of centre. Resting nose-to-tail length is 2.4–2.6 m (8–8.5 ft).

- For side lunging, choose a divider with an opening wide enough to permit easy lunging for rising or lying.

- The bottom pipe of the loop must not inhibit the ability to lunge over it (about 30 cm (12 in.) from the top of the mattress).

Loops and stall width

Loops define the width of the stall space for each cow. With 10 resting and 10 rising motions per day, cows benefit from greater ease when getting in and out of their stalls. Choose the right loop is critical in cow comfort and cow health.

Considerations for using loops:

- Obstructions to forward-lunging force cows to side-lunge through the loops.

- Loops designed for side-lunging have a wider opening between the top and bottom pipe (Figures 9 and 10). The top pipe becomes the neck rail and the bottom pipe must not obstruct lunging.

- Loops and narrow stalls designed to force cows to lay straight in the beds may contribute to injuries.

- Use imprint width to determine minimum stall width (about two times hook-bone width).

- Minimum width prevents wide resting positions.

- Wider stalls compensate for challenges in short stalls.

- Mount dividers on 127 cm (50 in.) centres for average-sized mature Holstein cows (for example, gives 122 cm (48 in.) of space).

- In practice, loops are being mounted on 127–137 cm (50–54 in.) centres to provide 122–132 cm (48–52 in.) of space, depending upon cow size or special needs.

- A loop that restricts the space at the back of the platform to 30–36 cm (12–14 in.) discourages cows from walking along the back of the stall.

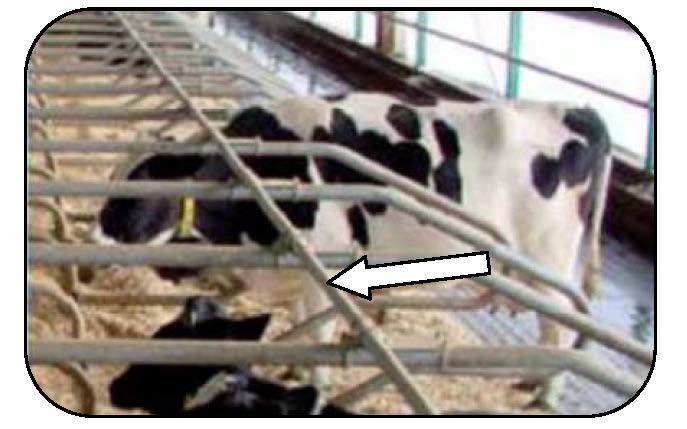

- A loop with the bottom pipe high enough above the bed will entrap hips and cows (Figure 11).

- The height of the bottom attachment pipe above the bed should be about 30 cm (12 in.) for easier side-lunging.

- Mount each loop or pair of loops to a support post or floor mount.

- Transverse mounting pipes for the lower ends of a loop may interfere with lunging and be a hazard.

- Transverse mounting pipes for the upper ends of loops may be a hazard in some but not all installations.

- Side-lunging loops are useful for renovating older barns with short stalls.

- The loop shown in Figure 24 has the lower pipe extended further to the rear of the stall before the pipe bends upward. The loops are supposed to force cows to lie straight in the stall. However, they are very shiny from cow contact and cows may get bruises from this style of loop.

- For a contrast, the loops shown in Figure 9 are bent differently. The lower pipe extends less to the rear of the stall before bending upward. This design provides ample space for the hips (61–69 cm or 24–27 in.) but prevents her from rolling under the loop.

- The downward slope of the top pipe of loops shown in Figure 9 allows cows to swing their heads over easily when exiting the stalls. They can do this with their front feet still on the bed. However, the loops shown in Figure 20 do not have that feature and cows must back out of the stall before turning.

End stalls

An end stall must provide space for backing around with the rump, swinging the head for turning out of the stall and resting postures. Otherwise, it becomes a one-way stall that cows do not like. Concrete curbs or walls in end stalls are hazards for injuries to hook bones.

Considerations for using end stalls:

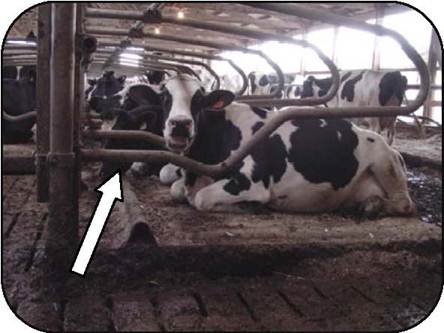

- Concrete curbs restrict normal leg posture and some cows avoid these stalls.

- Place water troughs on the outside wall or centre of a crossover rather than against the end stall (for example, to ease cow traffic flow through the crossover and to avoid wet beds).

- Use a stall divider (loop) for the end partition.

- Use a section of brisket locator or plastic pipe as an end curb.

Bed length and slope

Considerations for determining bed length and slope:

- Bed length in mattress stalls is the distance from the alley curb to the brisket locator.

- Use imprint length of the resting cow as a guide for determining bed length (1.2 times rump height).

- Bed length should allow cows to rest parallel to the dividers in the short position with tail and legs on the bed.

- Consider a 178 cm (70 in.) bed for Lactation 1 heifers that have a rump height of 147–150 cm (58–59 in.).

- Consider a 183 cm (72 in.) bed for mature Holstein cows measuring 152 cm (60 in.) at the rump.

- Bed length ranges from 173–183 cm (68–72 in.).

- The minimum bed length allows cows to lie straight with their forelegs extended over a 10 cm (4 in.) high brisket locator.

- High brisket locators or short beds force cows to lie diagonally or with their rumps over the gutter to attain the fore-legs forward resting posture.

- Stalls are seldom built with longer beds because they pose challenges with stall and cow cleanliness and the risk of mastitis.

- Build a slope of two to three percent into the concrete platform (higher at the front) (about 38–51 mm (1.5–2.0 in.) in a 183 cm (72 in.) stall)

- Too much slope may contribute to claw disease.

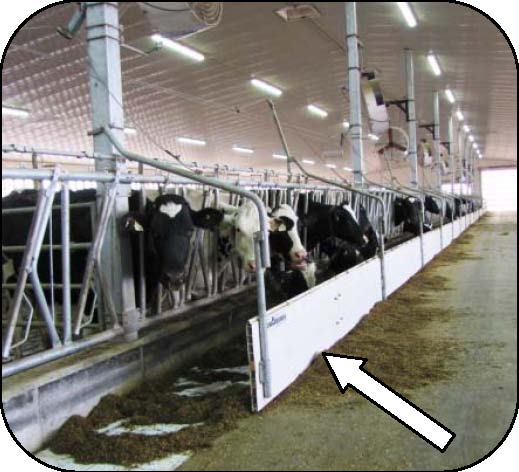

Stall length and height

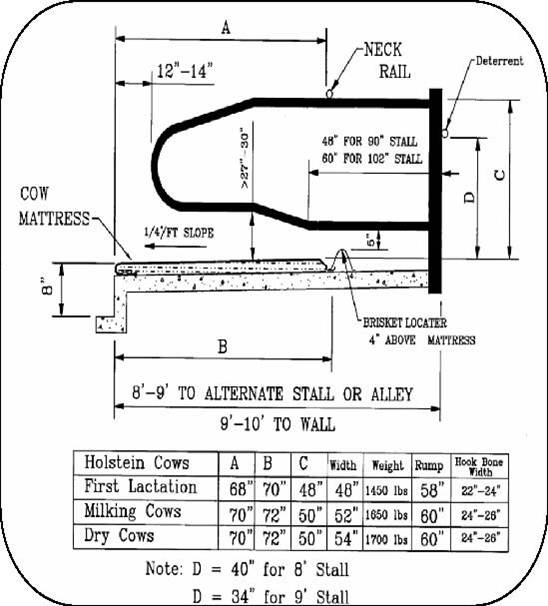

Stall length determines the comfort and cleanliness of the stall. Properly sized stalls keep the cows clean and improves lying time. Figures 12, 13 and 14 show typical stall dimensions to consider in designing a stall.

Considerations for designing stall length and height:

- Stall length from alley curb to a solid front is 3 m (10 ft) for normal rising and resting motions (Figure 15).

- Stall length for open front head-to-head stalls is 5.5 m (18 ft) for normal rising and resting motions (Figure 16).

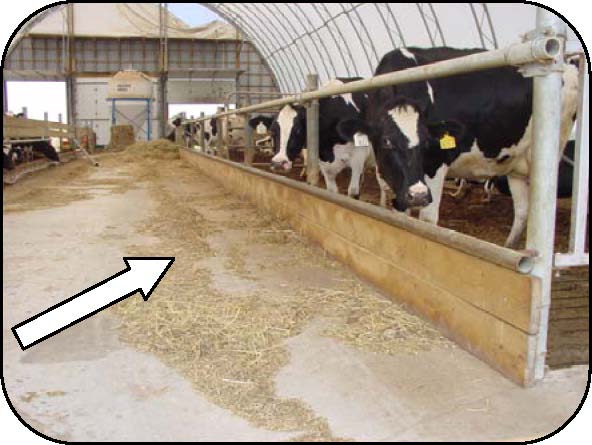

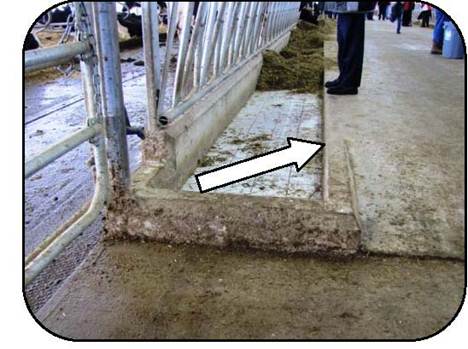

- Stall height is the difference in elevation between the alley and the stall platform.

- Stall height affects cow safety or comfort.

- Build the stall platform about 15 cm (6 in.) higher than the alley for barns with alley scrapers.

- Consider difficulty of entry or exit with high 25–30 cm (10–12 in.) platforms.

- Consider ease of doing reproductive examinations and artificial insemination - ergonomics for technicians and veterinarians.

- Tractor scraping and once-a-day cleaning often lead to building the stall platform higher than what is comfortable for a cow.

- The width of the alley, stocking density and frequency of scraping affect the depth of slurry in the alley.

- Adequate stall dimensions are important for fresh cow health and milk production.

Brisket locator

A brisket locator restricts the forward location of a cow lying in the stall. It defines the length of the bed measured from the rear curb to brisket locator. Brisket locators contribute to cleaner beds and cows and reduced risk to mastitis. Several design features may be useful for selecting a brisket locator (Figure 17).

Brisket locators should:

- permit the normal behaviours (stride when rising, legs extended when resting), greater hours of resting and restfulness and not restlessness in the stalls (figure 18)

- assure a safe resting place, free of hazards that entrap legs or challenge rising motions

- enhance stall cleanliness by positioning the cow's forward location relative to the alley curb

- be strong and durable to provide years of service

- be about 10 cm (4 in.) taller and wider than the mat or mattress

- A cow's foot will clear about 10 cm (4 in.) when taking the normal rising stride (forward step).

- Brisket locators higher and wider than 10 cm (4 in.) (for mature Holsteins) interfere with the stride, contribute to cows stumbling or falling forward and interfere with the forward resting position of front legs.

- Cows rest diagonally in the stall when high brisket boards interfere with normal resting postures.

Unwanted outcomes include diagonal resting, manure and urine on the beds, pressure sores on spines, restlessness and hock sores or reduced hours of resting.

Other design principles of brisket locators:

- Locators mounted to the platform allow cows to stretch their forelegs under the loop.

- Brackets on the loop restrict resting postures.

- Space between the brisket locator and bottom pipe of the loop should be no less than 13 cm (5 in.) to allow for the legs forward resting posture and prevent entrapment of a leg.

- Forward location may be, for Holsteins, 173 cm, 178 cm or 183 cm) (68, 70 or 72 in.).

- measure from the alley curb to the cow-side face of the brisket locator

- allows all body parts (including the tail) to rest on the bed

- provides the bed length needed to rest parallel to the loops

- Shape should be contoured and have a smooth surface.

- provides comfort or safety when cows extend and retract their legs over the locator

- Area in front of the locator is important for resting or rising.

- height similar to the stall platform

- provides a safe and comfortable surface for the foot during the rising stride

- provides a comfortable space for legs when extended while resting

- provides excellent traction (not slippery)

- assures ease of rising

- minimizes risks of stumbling or falling

- Consider merits or challenges of wooden boards, concrete curbs, nylon straps, metal or poly pipes or plastic curbs as safe and comfortable brisket locators.

- Some are excellent choices while others provide hazards and challenges (Figure 19).

- A 15 cm (6 in.) sewer pipe may not be a suitable brisket locator.

- A 8–10 cm (3–4 in.) sewer pipe may be a suitable brisket locator when mounted to the platform.

- Choose a smaller size for heifer stalls

Area forward of the brisket locator

Objects in the space forward of the brisket locator are obstructions to the head lunge and bob, the stride and resting positions for the front legs. This area may contain some bedding and be slightly higher than the stall bed (Figure 20).

The use of one support structure (for example, post or floor mount) for the loop in single stalls or pairs of loops in head-to-head stalls keeps the area unobstructed. Roof-support posts located between loops may force cows to stand and lie diagonally in the stalls.

Deterrent strap or pipe: open-front stalls

Open-front stalls provide cows with a convenient route for escaping a dominant cow, a cow in heat, equipment used to bed stalls or an aversive handler.

A deterrent bar or rope discourages cows from exiting through the front of stalls.

The deterrent must not interfere with the upward bob of the head (Figure 21).

Deterrent height above the bed (for example, 86-102 cm (34-42 in.)) varies with stall length and location of the mounting post.

A temporary installation and observation will help you to determine the best location.

The usual mounting point is the support post for the loops.

Deterrents may be wood, metal or poly rope (Figures 22 and 23).

In general, avoid using tie-down straps like those used in the trucking industry as they are a hazard. When ratcheted tight, the straps can cut a cow's hide if she becomes trapped by them.

Several management practices reduce the risk of cows trying to escape through stall fronts:

- Moving cows in estrus to a 'play pen' and choosing AI rather than 'running a bull' protects cows from pestering.

- Gentle handling must be the standard of care.

- Veterinarians and farmers successfully conduct reproductive examinations in open-front stalls without deterrent bars. A credit to gentle stockmanship.

- A brisket rail may act as a deterrent to prevent cows from crawling forward prior to rising (Figure 8).

Bedding

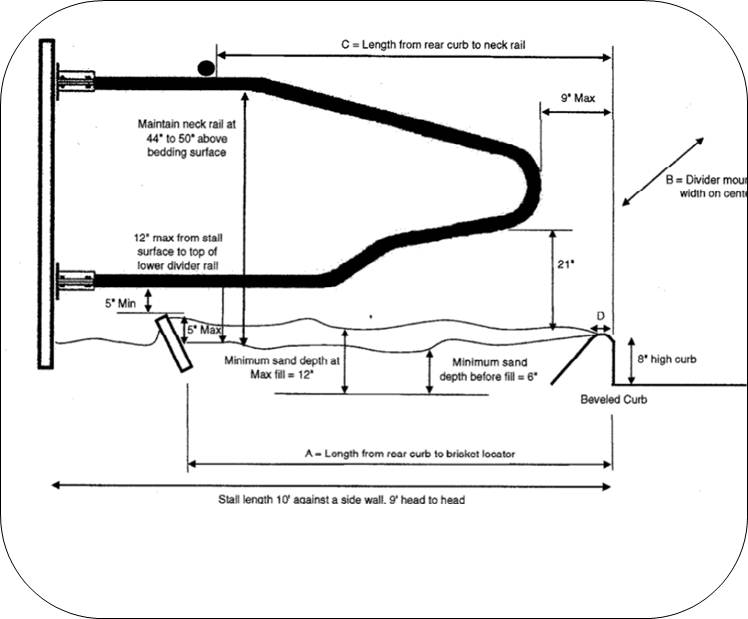

Sand-bedded stalls

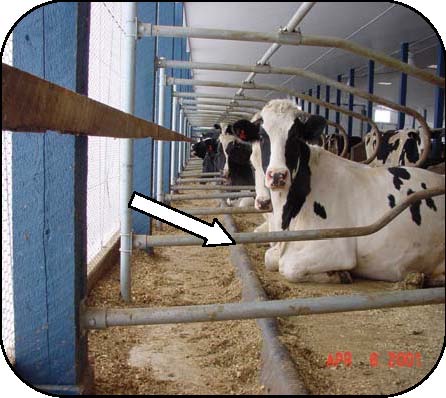

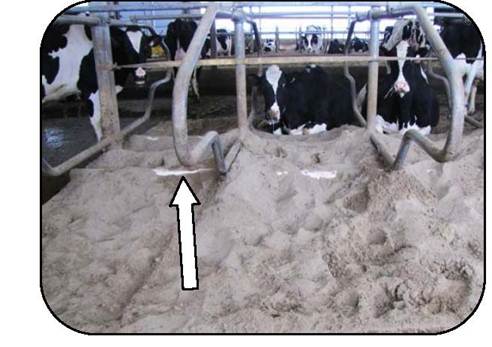

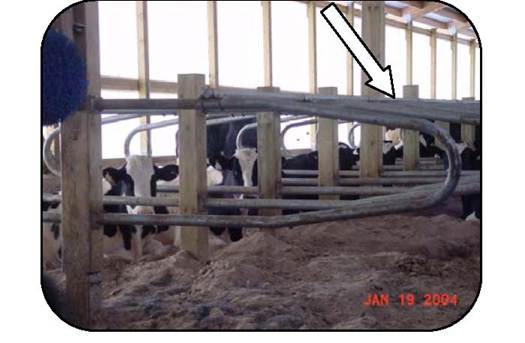

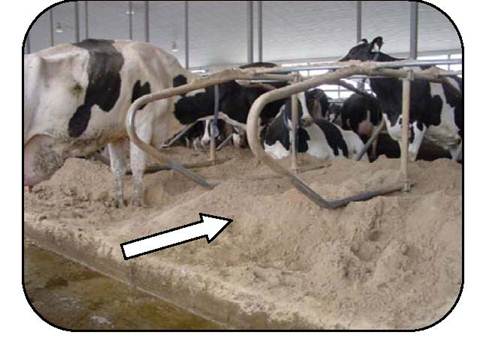

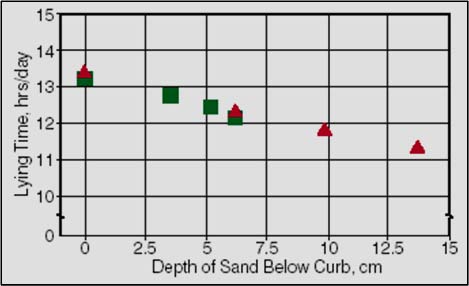

Sand bedding provides unique challenges for maintaining stall dimensions (Figures 24–27). Ideally, a sand bed should be slightly sloped and filled to curb height. Neck-rail height changes with the height of sand stored at the front of the stall. The effective bed length for sand-bedded stalls is the distance from the inside of the rear curb to the brisket locator when the sand is below the level of the curb.

Lame cows rise and go down easily in sand-bedded stalls but have difficulty in stalls with firmer beds.

A brisket locator can be mounted in a sand-bedded free stall.

The neck rail in most sand stalls is placed the width of the rear curb closer to the back of the stall than it is for mattress stalls. This neck rail location forces cows to perch in the stall rather than stand with their rear feet in the sand bed or on the concrete curb. This neck rail location aims to prevent cows from urinating or defecating in the sand bed.

The loop controls cow position and generally forces forward lunging. The bottom pipe is high enough to discourage cows from lunging through it, yet low enough to discourage cows from lunging under it.

Stall base and bedding

Concrete platforms require a cushion for a resting surface. An optimal stall surface provides thermal insulation, softness, traction, low risk of abrasion and ease of cleaning.

Common stall bases include rubber-filled or gel-filled mattresses, foam mats with rubber top covers, mats of various compositions, water beds, combination of rubber-filled mattress and sand, sand, compost, deep-bedded organic materials (for example, straw, sawdust, peat moss or manure solids). Mattresses or mats have a limited life expectancy for softness and require replacement after a few years in service.

Ample bedding is a best management practice in the Code of Practice for Dairy Cattle.

Benefits of ample bedding:

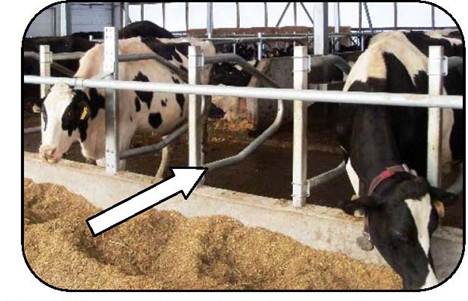

- Bedding provides cushioning and absorbency and reduces friction (Figure 28).

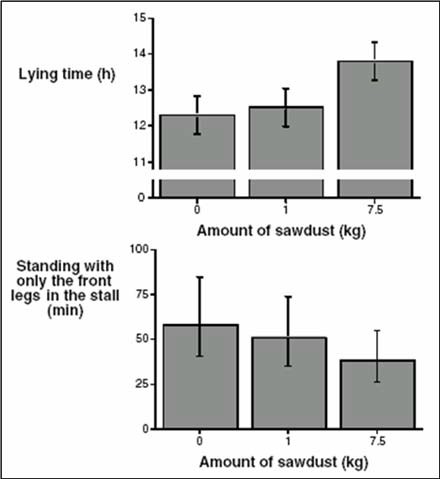

- Chopped straw, kiln-dried sawdust, kiln-dried softwood shavings, compost (manure solids) and peat moss are common bedding materials. Figure 29 shows laying and standing time with varying amount of sawdust bedding in stalls

- Absorbency (dryness) and traction are important.

- Hardwood shavings or wood chips are unacceptable bedding materials.

- Solid rubber mats require a very generous (for example, > 7.5 cm (3 in.) cover with bedding.

- Some 'soft' mats allow a 'basin' to form that collects urine and milk. This results in wet teats, udders and flanks and a hazard for mastitis. More slope on the platform may not succeed in getting better drainage from these beds.

- Some mats or top covers are slippery and become more slippery with straw and moisture.

Bedding: manure system and lame cows

The choice of manure system, commitment to stall maintenance and the ready availability of inexpensive bedding determine choices in stall design.

A once-per-day stall cleaning protocol may not be compatible with generous stall dimensions.

British Columbia research

University of Wisconsin

Stocking density and social turmoil

Stocking density refers to the proportion of cows to the number of stalls, the number of cows per square foot of bedded pack area, the inches of feed bunk space per cow, or the proportion of cows to the number of self-locks at a feed bunk.

Stall stocking densities >100% alter cow behaviour:

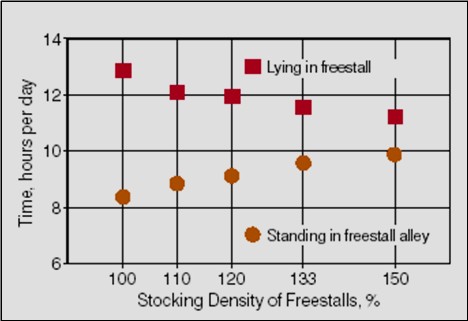

- Overstocking stalls increases standing time in alleys, reduces lying time and increases the risk of claw lesions (Figure 30).

- Overstocking a feed bunk (less than 76 cm (30 in.) per cow) increases the risk for ketosis and low early lactation production.

- Overstocking a pen or barn challenges cows, ventilation systems, manure handling and management.

proAction in Ontario requires stocking density to not exceed 1.2 mature cows per usable stall.

Social turmoil refers to distress amongst cows as they establish dominance patterns. Turmoil may last for 2 to 4 days after introduction of a cow or cows into an established group of cows. Weekly introductions (for example, on Thursday) into a dry cow pen may produce two days of turmoil and five days of calm. Daily introductions into a calving pen may result in constant turmoil in the group. Social turmoil has an adverse effect on cow behaviour and performance.

Bunk and manger feeding

Bunk Space

Bunk space describes the linear space of feed bunk space per cow in a pen.

Provide 76 cm (30 in.) of bunk space per cow including fresh cow and close-up cow pens to avoid cow displacements at the bunk space. Lack of bunk space increases the risk for fresh cow ketosis.

Feeding time decreases as stocking density increases. Dry matter intake decreases when all cows cannot eat at the same time. Overstocking at the feed bunk has an adverse effect on milk production in early lactation.

Avoid overstocking at the feed bunk to increase feeding activity and reduce competition.

Conventional building techniques result in 61 cm (24 in.) of bunk space per cow in 2-row barns and about 46 cm (18 in.) in 3-row barns.

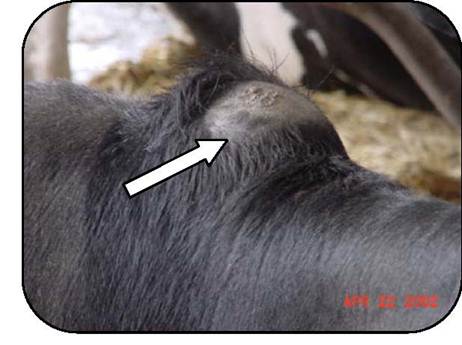

Feed bunk restraint

Feed bunk restraints prevent cows from escaping from their pens into the feed alley. Post-and-rail (pipe), cable, slant bar and headlocks are common restraints. Improperly designed restraints pose risk for neck injuries when the skin, the nuchal ligament and its bursae and the supraspinous processes of the first few thoracic vertebrae at the withers experience repetitive trauma (Figure 31). The injuries may be hair loss, gall, callus, hygroma or bursitis. Similar injuries occur when the top rail is too low on slant bar or headlock restraints.

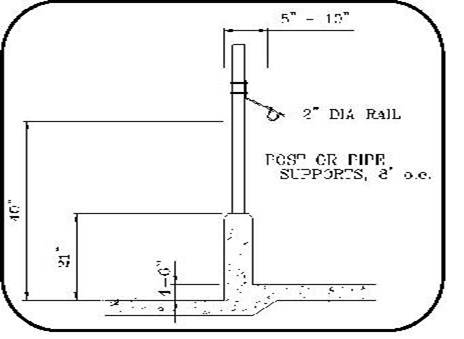

Post-and-rail restraints have a rail (pipe) attached either directly to a post or on a mount to locate the rail forward of the post and over the manger. (Figures 32, 35 and 36).

Pipes mounted on a pivot are a variant of the post-and-rail restraint. With this device, the larger cows in the group raise the restraint and spare smaller cows the burden. Cost may be greater than a single rail and there may be no cow comfort or practical advantage.

Considerations for feed bunk restraints:

- Rail height may be adjustable and should be raised or lowered to suit cow size in various pens.

- A mount may offset the rail about 15, 20 or 25 cm (6, 8 or 10 in.) over the feed bunk.

- Regardless of height, a rail or cable may blemish or injure necks (Figure 32).

- Feed rail height and the frequency of pushing feed up contribute to freedom from neck injuries.

- In barns where feed is not pushed up often, cows sustain injuries to the supraspinous processes, especially with a higher rail.

- Elevated feed alleys keep feed close to cows, reduce the risk of neck injuries or decrease labour.

- Displacements by boss cows are more common with post-and-rail or cable restraints.

- The feed alley must be wide enough to permit passage of feed wagons without damage to the rail. Measure the TMR wagon to be sure.

- Slant bar and headlock restraints are alternatives to consider.

- For most Holsteins, the manger wall should be 46–51 cm (18–20 in.) higher than the walk alley (cow's feet) to avoid injury to briskets. This height also permits the addition of self-locks later.

- Cows may be tipped into or fall into a manger. Therefore, mangers should not have a front or barrier in barns with post-and-rail restraints.

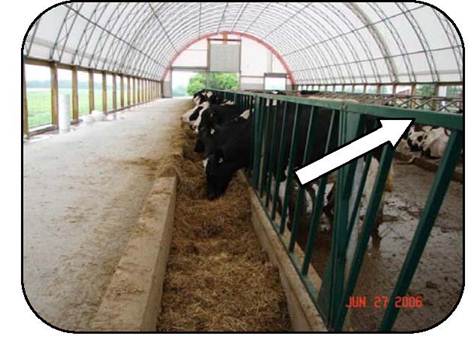

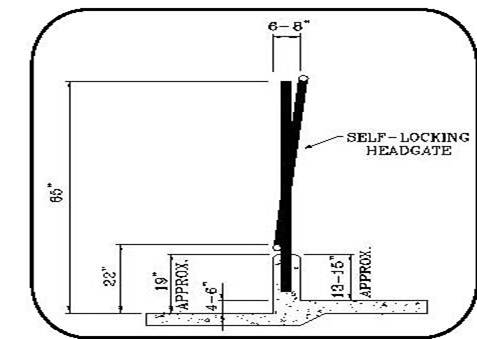

Self-locking headlocks prevent cows from escaping their pens into the feed alley and restrain groups of cows on days when examinations are necessary. Figure 34 shows typical self-locking headlocks at a feed bunk.

For headlocks and slant bar restraints:

- the top bar must be located higher than the withers height of the tallest cow to avoid neck injuries

- the restraints are built in panels, rest on the top of the manger curb, and are fixed to mounting posts

- the top of the panel may be offset over the manger by 15–20 cm (6–8 in.); (15-20 degrees) and

- the height of the concrete curb plus the bottom bar of the panel should be 51 cm (20 in.). Allow for the thickness of the bottom bar when building the concrete curb.

- headlocks and slant bar restraints minimize bullying, displacements at the bunk, wastage of feed or injuries to necks

- headlocks are handling facilities for those who do not build palpation rails

- since most headlocks are built on 61 cm (24 in.) centres, they do not provide the recommended 76 cm (30 in.) of bunk space per cow

Feed stalls have loops that separate each cow's feeding space. The stall may have an elevated platform that will require manual cleaning. The loops discourage displacement by boss cows. (Figure 35)

Manger (feed table) and feed trough

Manger is a critical component of dairy barn because improperly designed manger impacts the feed intake of cows. Cows should be comfortable in Manger while feeding and should be risk free for neck injuries.

Design considerations for mangers and feed troughs (Figure 36):

- Measure the curb height from the floor in the cow alley. Manger curb height should be less than the floor to brisket height of the smallest cow in the pen to reduce the chance of brisket injuries.

- Build the curb height 51 cm (20 in.) for post-and-rail restraints or 46 cm (18 in.) for slant bars or headlocks.

- Curb height will be 36–41 cm (14–16 in.) on the feed table side.

- The width of the feed table or bottom of a trough should be about 71 cm (28 in.) to keep feed within reach.

- The feed table or trough is 10–15 cm (4–6 in.) higher than the cow's feet.

- Build a concrete curb 15 cm (6 in.) wide to support posts.

- Bevel, smooth or round the curb edges on the cow and manger sides.

- Feed table height is chosen to minimize pressure on the soles of claws, maximize foot health and make eating more comfortable for cows.

- Choose an acid-resistant and relatively smooth surface.

- Ceramic tile, plastic or special concrete are common surfaces.

Sweep-in mangers allow simplicity of construction and ease of cleaning. Sweep-in mangers have the same elevation as the drive alley for delivering feed.

With sweep-in mangers, cows push feed out of their reach while sorting and eating requiring pushing up feed (Figure 37).

The intensity of the labour for pushing up feed varies with the technology (for example, brooms, snow shovels, ATVs or garden tractors with blades or brushes, skid steers or tractors) and the intensity of management.

Automated (robotic) feed pushers are available.

A feed trough may keep feed closer to cows, lessen stresses related to reaching for feed, minimize injuries to necks or reduce labour for pushing up feed (Figure 38).

The height of the front of a feed trough may be determined by the clearance needed for the discharge chute for the feeding wagon (TMR mixer).

An elevated feed alley acts as a feed barrier. A feed front may be constructed of concrete, plastic or wood for retrofitting sweep-in mangers. A recent innovation from an Ontario producer is a barrier that may be raised to clean the feed table and lowered to keep feed close to cows (Figure 39).

Steps and elevations

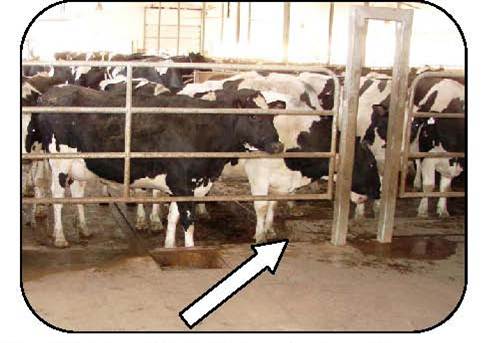

Steps are hazards for claw-horn disruption. Connective tissue that fixes the pedal bone to the claw relaxes at calving time and retightens within a few weeks. The pedal bone has greater mobility within the claw and there is greater opportunity for bruising of the sole and formation of sole ulcers.

The ideal barn would have only one step from the walk alley into the bed (Figure 40).

Considerations for steps and barn elevations:

- Tractor-scraped or slatted floor barns may have no steps at crossover alleys.

- Alley scrapers require a curb to run along.

- Crossover alleys may be lower in elevation (for example, 8 cm (3 in.)) than the stall platform (for example, 15 cm (6 in.)) relative to the floor.

- Sharp turns in return alleys or parlor exits are hazards for claw-horn disruption in fresh cows.

- Provide enough space for cows to turn in an arc while taking steps. Avoid narrow spaces where they must pivot on a back foot.

- Eliminate unnecessary steps into and out of pens, at crossovers or into milking parlors when designing or building free-stall barns.

- Barn drawings should show elevations, and these should be considered carefully for cow comfort and health.

Biosecurity

Biosecurity is about ways to prevent the spread of diseases within the barn or on the farm. Diseases of concern are spread in manure.

Consider the movement of air, manure, feed, cattle, equipment and people outside and within the barn. Design the barn to segregate manure from feed. Manure storage should be distant and down wind from the barn.

Consider traffic routes for people and cows, for feeding and bedding equipment, for moving manure, for delivering feed and for service providers and visitors.

Calving pens should not be adjacent to the parlor holding pen.

Outside the barn, lanes for moving feed should not cross routes used for hauling manure.

Inside the barn, consider designs without intersections for both cows and equipment:

- In the design of 2- and 3-row barns, tractors and TMR mixers or feed pushers do not have to cross cow alleys and cows do not have to cross the feed alley.

- A feed bunk filled by an overhead conveyor has no cow traffic through it.

- A feed-wall with outside feeding keeps feeding equipment outside the barn. With this design, there is no cow traffic across the feeding table (Figure 41).

- Perimeter feed alleys for 4- or 6-row barns keep feeding equipment out of cow alleys and cows out of feed alleys.

- A barrier on the feed table keeps feeding equipment out of the feed.

- Many barn designs have traffic intersections where workers' mucky boots or cows cross feed alleys.

Sanitation strategies help to prevent manure contamination of boots, tires and feed:

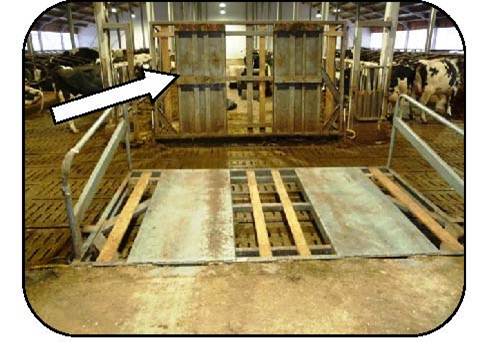

- A lift bridge allows cows to cross a feed alley without contaminating it with manure and urine.

- A lift bridge allows feeding equipment to cross a cow alley without getting manure on tires (Figure 42).

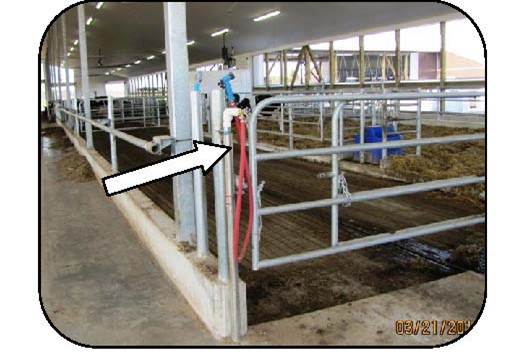

- A foot bridge allows people to cross cow alleys without contaminating their boots (Figure 43).

- Water outlets and hoses at strategic locations allow workers to wash their boots when exiting cow alleys and before entering feed alleys (Figure 44).

- Slopes and washing equipment allow cleaning of intersections at feed alleys.

- A curb on the end of the feed table keeps feed out of the feed-alley intersection.

- Guide visitors along clean routes, not cow alleys.

Summary

Free-stall is a popular housing option for milking cows. It provides comfortable living area and allows cows to move around freely exhibiting natural behaviours. It is important to properly design and size different components of free-stall to provide comfortable living area. Well-designed free-stall improves cow comfort, cow health and welfare issues. It helps to improve productivity.

Footnotes

- footnote[1] Back to paragraph Drissler M, Gaworski M, Tucker CB, Weary DM. Freestall maintenance: effects on lying behavior of dairy cattle. J Dairy Sci 2005; 88(7):2381-2387.

- footnote[2] Back to paragraph Tucker CB, Weary DM, Fraser D. Free-stall dimensions: effects on preference and stall usage. J Dairy Sci 2004.

- footnote[3] Back to paragraph Drissler M, Gaworski M, Tucker CB, Weary DM. Freestall maintenance: effects on lying behavior of dairy cattle. J Dairy Sci 2005; 88(7):2381-2387.

- footnote[4] Back to paragraph Tucker CB, Weary DM, Fraser D. Free-stall dimensions: effects on preference and stall usage. J Dairy Sci 2004;

- footnote[5] Back to paragraph Cook NB, Bennett TB, Nordlund KV. Effect of free stall surface on daily activity patterns in dairy cows with relevance to lameness prevalence. J Dairy Sci 2004; 87(9):2912-2922.

- footnote[6] Back to paragraph Tucker CB, Weary DM. Bedding on geotextile mattresses: how much is needed to improve cow comfort? J Dairy Sci 2004; 87(9):2889-2895.

- footnote[7] Back to paragraph Fregonesi JA, Tucker CB, Weary DM. Overstocking reduces lying Time in dairy cows. J Dairy Sci 2007;