Faba beans as protein in livestock feed

Learn about the nutritional value of faba beans, why they are a good source of protein and how to plant and easily process them on-farm. This technical information is for Ontario livestock producers.

ISSN 1198-712X, Published October 2016

Introduction

With many feed ingredients available to producers, protein is still a sought after nutrient, not necessarily due to a lack of availability, but the fluctuating, yet increasing costs associated with protein.

One potential solution may be the botanically named Vicia faba, common name "faba bean". This bean is also known to have various other common names such as "horse bean", "field bean" and "broad bean" which is an Italian translation of the word 'fava' and probably the closest sounding to the name faba bean.

Nutrition

The common reason for livestock producers to plant faba beans is to obtain a protein source that is homegrown and that can easily be processed on-farm, as they contain little oil. They also do not contain anti-nutritional enzymes and therefore do not need roasting.

Faba beans are related to lima beans and contain approximately 30% protein. They provide a good source of energy from starch. Figure 1 shows a sample of a 2015 faba beans nutritional analysis report, which had average results for that harvest season with a crude protein ranging from 28%–33% and soluble protein values between 11.5%–17%.

| Test: protein | Dry basis | As is |

|---|---|---|

| Protein % (N × 6.25) | 30.83 | 26.66 |

| Soluble protein (%) | 16.5 | 14.27 |

| SP % of CP | 53.52 | Not reported |

| ADF-CP % (ADP) | 0.31 | 0.27 |

| ADP as % of CP | 1.01 | Not reported |

| NDF-CP % (NDP) | 3.1 | 2.68 |

| NDP as % of CP | 10.06 | Not reported |

| UIP Bypass Est. % of CP | 28.34 | Not reported |

| Test: fibres | Dry basis | As is |

|---|---|---|

| Acid detergent fibre (ADF) (%) | 10 | 8.65 |

| Neutral detergent fibre (NDF) (%) | 13.57 | 11.73 |

| Lignin % NDF | 0.07 | 0.06 |

| Test: non-fibres | Dry basis | As is |

|---|---|---|

| Fat (%) | 0.25 | 0.22 |

| Water Soluble CHO (%) | 8.87 | 7.67 |

| Starch (%) | 32.8 | 28.36 |

| Starch as % of NFC | 62.3 | Not reported |

| Non fibre carbohydrate (%) | 52.65 | 45.53 |

| Test: minerals | Dry basis | As is |

|---|---|---|

| Ash (%) | 5.8 | Not reported |

| Calcium (%) | 0.37 | Not reported |

| Phosphorus (%) | 0.78 | Not reported |

| Potassium (%) | 1.32 | Not reported |

| Magnesium (%) | 0.29 | Not reported |

| Sodium (%) | 0.03 | Not reported |

| Copper (ppm) | 19.68 | Not reported |

| Iron (ppm) | 130.68 | Not reported |

| Manganese (ppm) | 16.69 | Not reported |

| Zinc (ppm) | 50.41 | Not reported |

| Test: energy | Dry basis | As is |

|---|---|---|

| TDN (%) (ADF based) | 86.77 | Not reported |

| Net Energy (lac) Mcal/kg (ADF based) | 1.74 | Not reported |

| Net Energy (gain) Mcal/kg (ADF based) | 1.66 | Not reported |

| Net Energy (maint) Mcal/kg (ADF based) | 2.37 | Not reported |

| WTDN (OARDC) | 81.19 | Not reported |

| WNEL (OARDC) | 2 | Not reported |

| WNEG (OARDC) | 1.47 | Not reported |

| WNEM (OARDC) | 2.15 | Not reported |

Canadian research has shown no significant difference in milk production when feed rations contained either soybean meal or faba beans as the protein source. The energy provided by faba beans by comparison is greater than soybean meal, but lower than barley. They are similar to peas in that they are a good source of lysine at a comparable 2:1 ratio of lysine:methionine. Faba beans are also rich in thiamin and phosphorous.

| Ingredient | Crude protein % | Starch % | NEL (Mcal/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Faba bean | 30–35 | 30–40 | 1.9 |

| Soybean meal | 46 | 5 | 1.65 |

| Canola/rapeseed | 36 | 6 | 1.5 |

Source: Dairy Vision Consulting

Most varieties available within Canada are produced in Germany and the Netherlands. Early varieties were known to have an undesirable level of tannin, found mainly in the hull which reduces protein digestibility. Although the tannins give the bean more flavour and ruminants can digest the tannins, monogastrics cannot. Over time, varieties have changed to reduce tannins significantly. At the flowering stage, it is possible to see whether the variety contains tannins, if the plant has a purple or pink flower. These are generally used for the food industry. Those without or extremely low amounts of tannins will have a white flower and include varieties such as Imposa, Snowbird and Tabasco.

Planting

Faba beans should be inoculated to aid in a more even distribution and quicker nodule formation for maximum nitrogen fixation. Like other pulses, they are a practical crop for their remarkable nitrogen fixing ability, limiting the need for additional nitrogen for the subsequent crop. Faba bean plants use a fairly high amount of phosphorous to promote the development of the root system and seedling growth. Depending on the available phosphorous in the soil, phosphate can be banded with the seed, if required. Studies have shown that phosphorous aids in nitrogen fixation and improves drought tolerance.

Faba beans can be planted with corn or soy planters, air flow drill, seed drill, or if needed, an alternative seeding mechanism for larger beans as they may cause flow problems in distribution systems with smaller hose sizes. Row widths have varied, depending on preference, from 19–76 cm (7.5–30 in.) widths. The most common width is 38 cm (15 in.) The suggested plant population is 180,000 seeds per acre at a depth of 3.8–5 cm (1.5–2 in.). Some values in this fact sheet are in imperial measurements, reflecting common usage in the feed industry.

Generally, it is recommended that planting is done by the end of the first week of May, with some producers setting May 7th as the cut-off date. Faba beans are frost tolerant and can be put into the ground when the soil temperature is around 3°C. Delayed planting has been shown to reduce yield due to late maturation and drought stress when high temperatures are experienced at the time of flowering. A difference in planting time of 2 weeks can decrease yields by as much as 32%.

Growing season

Faba beans have a reasonably long growing season. Being relatively frost tolerant at the seed stage, they can be planted early without fear of frost kill. However, they do not survive fall frosts. They thrive under cool growing conditions, adapting well to moisture variations, but do not grow well in hot, dry climates.

Seeds should be sown in a weed-free field. They are poor competitors to weeds, especially at the seedling stage, since emergence and early development is slower than many other crops. Upon crop emergence, the field should be inspected for frequency and distribution of weeds as pre-emergent glyphosphates may provide effective treatment. Herbicides can also be used, but are thought to be less effective than pre-emergence treatments.

In general, the plants grow to a height of 0.9–1.5 m (3–5 ft), depending on growing season and variety. Once the flowering starts, it continues to grow and flower up the plant, while the bottom flowers become pods, see Figure 2. A flower cluster can produce up to six pods each up to 10 cm long and up to 1.5 cm wide with 4–6 beans per pod.

Production and yield

Western Canada started the commercial production of faba beans in 1972, as a substitute for soybean meal, primarily in livestock rations. In recent years it has also replaced canola in diets. In 2013, it was estimated that Alberta grew close to 6,475 ha (16,000 acres) of faba beans. In Ontario however, the acreage has been much less, but it is increasing. Southern Ontario planted around 162 ha (400 acres) of faba beans in 2015. In 2016 that number increased to around 405 ha (1,000 acres) in southern Ontario. Northern Ontario reached over 810 ha (2,000 acres). Due to their yield, less acreage is needed to grow the same bushel weight on a hectare/acre when compared to soybeans. In 2014, the average soybean yield for southern Ontario was 45.5 bu/acre where faba beans yielded approximately 85 bu/acre. That same year, canola averaged 43.1 bu/acre.

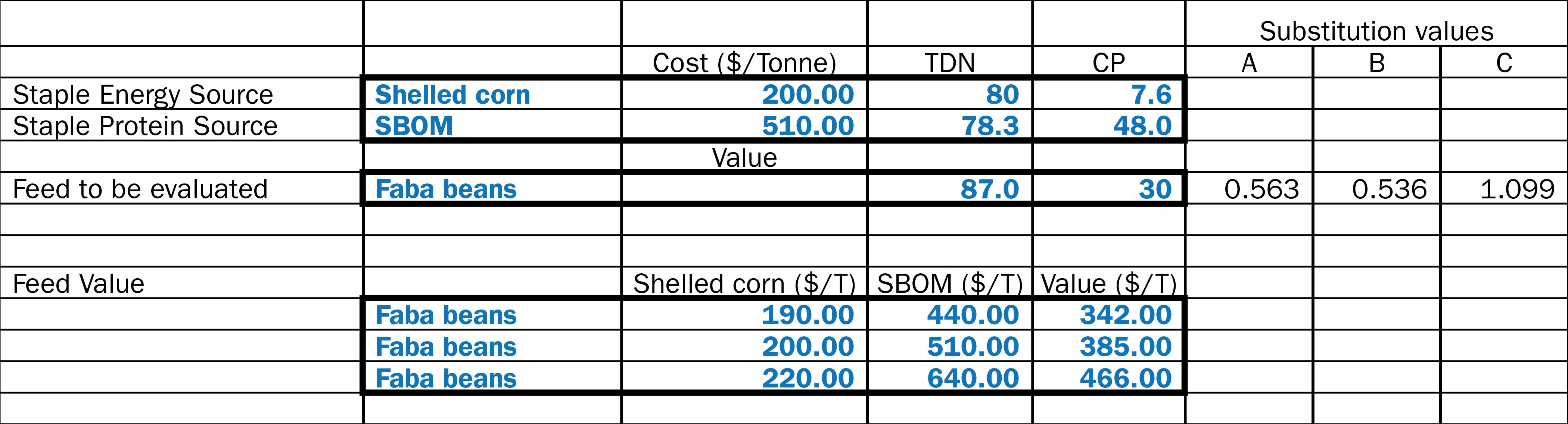

In terms of the value of faba beans per tonne (36.7 bushels/tonne), Figure 3 demonstrates how the Petersen's equation can be used to calculate the value of alternative feeds, in this case faba beans. Values based on their protein and energy contents are used in comparison to the nutritive value and cost of corn and soybean meal.

In addition, corn and soybean meal total digestible nutrients (TDN), and crude protein (CP) values are used to obtain substitution values A, B and C.

The substitution values are an indication of the rate at which the test feed must be fed to supply the same nutrients as the staple sources it replaces. One tonne of feed to be evaluated replaces 'A' tonnes of energy source plus 'B' tonnes of protein source in the ration. If 'C' is greater than 1, nutrient density increases and feed required per animal will be lower. If 'C' is less than 1, the use of the feed being evaluated decreases nutrient density and will require greater feed intake. Figure 3 shows the feed value of faba beans using three different costs, per tonne, for the soybean meal and corn since these values change consistently. In Figure 3, the value of faba beans ranges between $342–$446, as the value of corn and soybean meal ranges between $190–$220 and $440–$640 per tonne, respectively.

Petersen's equations were developed to provide a fast and easy cost comparison for alternative feeds.

Disease pressure and control

There are a few diseases that could potentially affect the faba bean during its growing season. Depending on the growing conditions, gray mold (Botrytis), white mold (Sclerotinia), seedling blight and foot rot can negatively affect the faba bean. Foot rot and seedling blight are caused by warm temperatures, whereas both mould strains are caused by cool temperatures. Wet soil conditions favour all three diseases. In narrower row spacing, mould may be more prominent than in wider spacing, due to trapped moisture in wet conditions.

Treatment and prevention methods are disease specific. For example, while fungicide is effective on white and gray molds, it has no effect on foot rot because it will be too late once the symptoms appear, and the product used is not carried down to the roots. In the case of foot rot, using treated high quality seeds would be the best prevention method. Like many other crops, the faba bean is affected by pests such as aphids, leaf hoppers, pea leaf weevils, grasshoppers and the most common, the lygus bug. Scouting at the pod development stage will help monitor lygus bug populations, and if needed, can be controlled with an insecticide.

Harvest

Faba beans take about 110–130 days to mature, depending on the variety and growing conditions. As the faba beans mature, the lower leaves darken and fall off. Subsequently, the pods turn black and dry progressively up the stem. At the time of maturation, focus should be given to the bottom pods. Generally, around the last week of August, the plant will be mature and 80%–85% of the bottom pods will have darkened at which time they are ready to be dried down with a spray, also called desiccation.

Desiccation is essential since not all the pods will dry at the same time, like the head of wheat does. Approximately 8–10 days after desiccation, the beans are ready for harvest. There is some variation between provinces as to when to desiccate, but all fall within 80%–90% blackened pods. As the plants are left standing and fully mature the chances of shattering increases. As drying continues to 12%–14% moisture, caution is needed as the plants are dry enough for the pods to fall off with a simple touch.

Preferably, pods can be combined between 16%–18% moisture and aerated to 14% moisture for storage. If the moisture at harvest is higher, a two-stage drying method is recommended, separated by a day to allow for the moisture to move towards the surface of the seed. If heat is required for drying, it should not exceed 32°C to prevent hardening of the seed coat.

Drop distances must be minimized to reduce cracking. As a quick rule of thumb for testing their moisture content, faba beans can be bitten through and if the texture is cheesy, they are over 15% moisture. If they are hard and remain intact when biting them, they are under 15% moisture. On farm processing for faba beans can be done with a roller mill or a 10 mm (0.38 in.) screen on a hammer mill or hay buster.

Swathing is another method by which faba beans can be harvested. The optimum time to swath a faba bean plant is when 25% of the plants in the field are starting to show black up to the third pod from the bottom. They are then left to dry and combined when the moisture content of the bean is at 18%–20%, preferably in the morning as dry-down may continue during the day and prevent shatter losses if moisture content decreases. Harvested beans can then be dried down further to 14% moisture content for storage.

In addition to harvesting the beans to dry-down, other options like high moisture faba bean and harvesting the whole plant for use as forage are options that are being pursued as well. Faba bean silage is palatable and can be harvested as a direct cut or wilted down to 30%–35% dry matter with an end result of approximately 17%–18% crude protein.

Faba beans are similar to many other pulses, such as dried peas and beans; they can be fed in various ways. Likewise, they are a protein source that can be fed to monogastrics and ruminants. Consequently, the faba bean has certainly proven to be an excellent feed source around the world for decades and continues to do so.

Acknowledgement

This fact sheet was written by Anita Heeg, feed ingredients and by products specialist, OMAFRA, Woodstock.

The author would like to acknowledge Dairy Vision Consulting, distributor of the Faba Bean Seed, for their contribution of information to this fact sheet.