Feeding dairy cattle to reduce excess nitrogen output

Learn proactive approaches to reduce excess nitrogen output by modifying dairy cattle diets.

ISSN 1198-712X, Published July 2003

Introduction

Nitrogen is an essential part of many different aspects of operating a sustainable dairy farm. Dietary protein contains nitrogen (N) that provides amino acids for growth, maintenance and milk production. At the other end of the farming spectrum, N is essential for maintaining soil composition for sustainable and economical crop production.

When manure N is applied in excess to crop requirements, the excess has the potential to pollute surface and well water resources. Nitrogen, as nitrate, can be harmful to human health when it is present in drinking water. Another consideration with manure N that is growing in importance is the loss of volatile N (as ammonia) into the atmosphere. Ammonia reduces air quality because of odour, and nitrous oxide is a potent greenhouse gas that contributes to global warming.

Dairy farmers are taking steps to manage excess N. However, a way to reduce excess N that can get overlooked is nutritional management. This is a proactive approach to reducing the possibility of excess N excretion before it becomes harmful to the environment.

There is a direct link between N in feed and N in feces and urine. An effective approach to reduce N excretion is to feed animals more accurately on dairy farms. Using nutrition to reduce excess N excretion is 4 times more efficient than adjusting manure storage facilities and application rates.

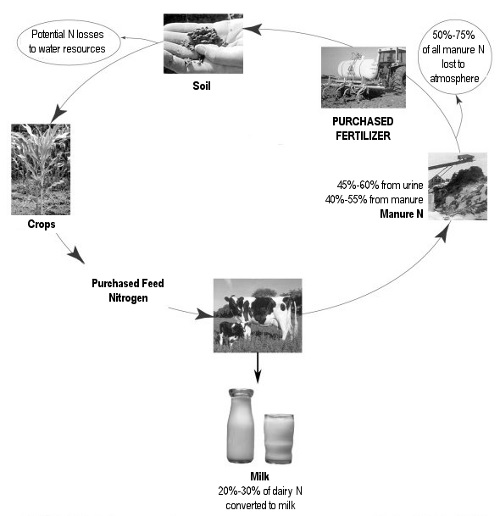

Research in North America indicates that on a typical dairy farm the amount of N imported onto the farm in the form of feed, fertilizer and through N fixation by legumes exceeds exports of N as milk or meat by 62%-79%. The importation of N in the form of purchased feeds represents 62%-87% of the excess N on dairy farms. The potential to reduce excess N through better nutrition is, therefore, an area where significant improvements to N management can be made. A typical cycle for N on a dairy farm is shown in Figure 1.

Nutritional Opportunities

Dietary crude protein (CP) is the overall indicator of N content in feeds. Crude protein for dairy cattle is classified into categories depending on how it is digested. Protein categories include ruminally degradable and ruminally undegradable (also known as by-pass) protein. As well, degradable protein is divided into rumen-soluble and insoluble categories. Nutritionists use chemical composition for ingredients to formulate rations that meet milk production requirements in an efficient and cost-effective way.

An expression often heard is 'feeding the rumen'. This means that ruminants are efficient when they make a lot of microbial protein and volatile fatty acids (VFA) used for making milk. To ensure that rumen fermentation is efficient there have to be adequate quantities of ruminally available protein together with necessary readily fermentable carbohydrates to maximize the production of microbial protein. A greater supply of microbial protein lessens the need for dietary inclusion of purchased protein, which would reduce N input and, therefore, N excretion.

An imbalance in protein or energy reduces ruminal digestive efficiency. For example, excessive ammonia absorption from the rumen leads to urea being produced in the liver that is excreted in urine. Excess dietary protein primarily results in higher urinary excretion of urea, which is the biggest source of ammonia that is lost into the environment from dairy cattle.

Ration balancing, as its name implies, avoids nutritional imbalances and inefficient nutrient use. Imbalances that create inefficient use of protein can be caused by inadequate or excessive supply of dietary protein fractions or fermentable carbohydrate. In Ontario, a common cause of inefficient protein use is excess supply of rumen degradable protein from alfalfa silage in the diet.

The requirement for protein to support high milk production can make the idea of reducing it in the diet seems unwise. However, the goal is to avoid inefficient protein utilization, not to reduce dietary protein below animal requirements.

The opportunities to better manage N in the diet are easier to spot when you start to look at the whole nutritional program. The following is a list of things that contribute to dietary protein overfeeding:

- Rations balanced infrequently

- the dietary supply of nutrients should evenly match the cows' needs, or inefficient nutrient use can result.

- One-group feeding programs

- this strategy over-feeds protein to those cows with milk production less than the quantity targeted for the whole group.

- Rumen-degradable protein (RDP) too high

- Ontario dairy rations often have a tendency to include too much RDP in the ration from alfalfa silage.

- Feeding refusals to heifers

- strategy that usually results in excessive N intake and excretion from the replacement group.

- Lack of regular forage analysis

- forage chemical composition varies widely. Feeding protein more precisely depends on having accurate knowledge of the ration ingredients.

Potential Impact

The opportunity to reduce N through nutritional changes will depend on what is feasible on a particular farm. For example, a one-group total mixed ration (TMR) overfeeds protein to all cows that are producing milk below the level balanced for by the ration. Switching from a one-group TMR to a two-group TMR system will reduce protein feeding by 15%-20% on a yearly basis and will reduce annual manure N output by a similar proportion. However, weighing this saving against the extra time required for feeding and mixing is an individual decision that depends on herd size, available labour and equipment.

Using Milk Urea Nitrogen (MUN) Data

Monitoring milk urea nitrogen values provides a practical way to monitor the dietary protein efficiency of dairy cows. A study of Ontario dairy farms reported that the average MUN value was 13.9 mg/dL. About 15% of herds have MUN values above 15 mg/dL, which is considered relatively high.

MUN values vary considerably from cow to cow, so MUN facts are best used to gauge the efficiency of groups of animals. MUN concentrations also vary with the time of year, with highest levels measured in the summer. Monitor MUN regularly over time to provide an accurate picture of the efficiency of use of dietary protein on individual farms.

As expected, higher MUN concentrations are linked to high levels of crude protein, rumen undegradable protein and rumen degradable protein in the diet. Lower MUN concentrations are associated with greater amounts of dietary energy, non-structural carbohydrates and lower protein to energy ratios. This reflects the importance of evaluating both the energy and protein in diets when trouble-shooting unusual MUN results.

A project at the University of Maryland on the use of MUN testing to improve dairy cow nutrition showed benefits for reducing N excretion. Monthly MUN results and management guidelines that were given to participating farmers resulted in 44% of producers reformulating their rations. Project participants achieved lower MUN values (by 0.52 mg/dl) compared to other farms in the area. The researchers calculated that the 472 farms in the study would save 126 tonnes of excess N per year from entering water resources.

Seven Ways to Feed Less Nitrogen

- Adopt a "do more with less" attitude. The "more is better approach" isn't true when it comes to efficient use of dietary N. A good measure of efficient milk production is a measure of your return over feed costs.

- Routinely sample your forages for nutrient content. The latest computer software used to balance dairy rations will not provide accurate results if book values or out of date forage analysis are used.

- Monitor and evaluate milk urea nitrogen (MUN) concentrations. Reformulate rations if necessary.

- Feed high quality forages. Higher quality forages are more digestible than poorer quality ones. Improved digestibility can improve the feed efficiency of cows. A forage strategy should be based on protein and carbohydrate quality, not just yield.

- Balance rations regularly and whenever ingredient or forage changes occur.

- Use processing techniques for grains or corn silage to improve nutrient digestibility.

- Have rations balanced for heifers. Heifers contribute to manure N output and are often overlooked in nutritional programs.

Benefits of Reduced N Output Through Nutrition

- Efficient way to manage manure N

- Improved air quality

- Reduced odour from ammonia

- Maintain or improve productivity while controlling or lowering feed costs

- Reducing N output reduces potential risk to water resources

Figure 1. Cycle of nitrogen on a dairy farm (diagram courtesy of Carolynn Gilchrist, OMAF).