Fungal disease of cruciferous crops

Learn about identification and disease control options for fungal diseases of cruciferous crops.

Introduction

Disease management is important for producing acceptable yield and quality of cruciferous crops such as cabbage, cauliflower, canola, rutabaga, grown for the fresh market, the processor, and for storage. Diseases caused by viruses, bacteria, and fungi, as well as physiological disorders, are all found in cruciferous crops in Ontario. This fact sheet discusses the biology, recognition, and management of diseases of crucifers caused by fungi.

Damping-off and wire-stem

Damping-off disease affects crucifer seedlings grown in flats and seedbeds, or in the field. Damping-off is normally caused by soil fungi such as Pythium and Rhizoctonia. Seed and young seedlings are attacked and may rot before they emerge or topple over a few days afterwards. When older seedlings are attacked by Rhizoctonia, the lower stem becomes constricted and dark-brown near the soil surface, a symptom called wire-stem (Figure 1). Such plants may die when stressed, break over in strong winds, or produce a stunted, unmarketable crop.

Disease management

- Avoiding damping-off begins with the use of vigorous, treated seed, pasteurized soil in new or disinfested flats and disinfested equipment and greenhouses.

- Avoid overcrowding of the seedlings to improve ventilation and drying-off of the crop and soil. Damping-off fungi thrive under moist conditions.

- Plant seed at the proper depth in well-prepared, moist, warm soil. Retarded seed germination and emergence make seedlings more susceptible to damping-off fungi. Seeding outdoors should be no deeper than 4.0 cm at a soil temperature of at least 10°C.

- Soil amendments such as composted tree bark, when added to the potting mix, have been shown to suppress damping-off.

- In greenhouses and cold frames, water seedlings only as necessary, with pre-warmed water, ensuring adequate drainage. Waterlogged soils promote damping-off.

- Maintain optimum growing conditions. Plants which are "leggy" from insufficient light are weak and prone to attack by pathogenic fungi. Avoid excessive fertility which promotes succulent growth or salt accumulation, both of which favor disease. Banding fertilizer close to the seed may delay emergence. Additional management practices are suggested in OMAFRA Publication 363, Vegetable Production Recommendations or damping-off and wire-stem.

Black-leg

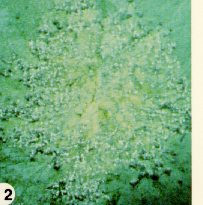

Black-leg, caused by Phoma lingam (Leptosphaeria macutans), is of major concern in crucifer production. Sources of the fungus include infested seeds, cruciferous weeds, and residues of cruciferous crops remaining in or on the soil. The fungus often kills seedlings or produces sunken, black cankers at the stem base which stunt the growth of surviving plants (Figure 2). Yellow to brown, circular spots with grey centres appear on the leaves. The presence of tiny, black bodies (pycnidia) on these cankers or leaf spots is characteristic of black-leg (Figure 3). The black bodies contain millions of spores of the black-leg fungus which ooze out and spread during wet weather.

Control measures for black-leg are similar to those for bacterial black rot and include treatment of seeds with hot-water or fungicide, and avoiding work in an infected field when foliage is wet. However, rotation with non-cruciferous crops and complete control of susceptible cruciferous weed hosts for four years are recommended if black-leg has been severe. Because disease progresses rapidly in wet conditions, crucifers should be planted in well-drained fields which dry out quickly.

Club-root

Club-root, caused by Plasmodiophora brassicae, is a destructive soil-borne disease which affects nearly all cultivated, as well as many wild and weed members of the cabbage family. The fungus enters root hairs and wounded roots, and multiplies rapidly, causing abnormal enlargement of the underground stem, taproot, or secondary roots (Figure 4 and Figure 5). These roots often decay before the crop has matured, releasing many resting spores which can survive for a decade in the absence of a susceptible host plant.

Infection and disease development are promoted by acidic or neutral, cool, wet soil, and are spread in contaminated soil, water, manure, or on equipment. However, club-root can occur in alkaline soils when inoculum levels are high, soil moisture is greater than 70% of field capacity, and temperatures are favorable (17-23°C).

Because there are several races or strains of the club-root fungus, cruciferous crops bred for resistance often give inconsistent results when grown in different locations. Due to its long persistence (10 years or more) in soil, the fungus is not readily avoided by crop rotation. Growing crucifers in well-drained, warm soil, eradication of related weed hosts, fungicidal soil drenches, and lime application to maintain pH above 7.2 are, when combined, the most successful methods of control. The addition of limestone to bring soil pH over 7.2 is the best means of control. Agricultural limestone takes a minimum of one year to effectively change the pH. For faster activity a minimum of 1700 kg/ha hydrated lime can be added (regardless of soil pH) at least six weeks prior to field transplanting. Hydrated lime changes soil pH only temporarily. Agricultural limestone is effective for several years.

It is important, however, to use clubroot-free locations for outdoor seed beds. Do not add hydrated lime in seedbeds, as it may mask the presence of the fungus, and allow it to move with the transplants to the field, where subsequent infection may occur if soil pH is favorable.

When transplanting, discard all plants in a lot if clubroot is found on any seedling. Others may be infected and not yet show symptoms. If transplanted, they will infest that field with the fungus.

Fusarium yellows

Symptoms of Fusarium yellows or wilt, a soil-borne fungus, caused by Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. conglutinans, resemble those of black rot. Affected plants are stunted, lopsided, yellowed, lose most of their lower leaves, and have a brown to black discoloration in the veins (Figure 6 and Figure 7). However, yellows may be distinguished from black rot because leaf dieback progresses from the petiole or midrib outwards, affected leaves are usually curved laterally, leaf margins may have reddish-purple discoloration, and pockets of dark discoloration are not associated with the vascular system when crucifers are infected with the yellows fungus. Fusarium yellows is a "hot weather" disease, and thus is rarely seen in early cole crops.

Due to its persistence in soil without host plants, this fungus is very difficult to control by crop rotation and other methods. Monogenic dominant resistance has been incorporated into many varieties of cabbage and some radish and Brussels sprouts, but none is currently available in cauliflower and broccoli. This resistance is noted in many cultivars listed in OMAFRA Publication 363, Vegetable Production Recommendations.

Sclerotinia blight

This disease, also known as white mold or white rot, is caused by the fungus Scierotinia sclerotiorum. This fungus attacks not only crucifers but also a wide variety of other crop plants in field and storage. Plants are infected from seedling to maturity by wind-blown spores, or directly by fungal strands arising from hard, black fungal bodies called sclerotia. Water-soaked spots appear anywhere on the plant, usually on leaves nearest the ground, or on the head. Affected tissue often turns grey, giving rise in wet weather to fluffy white mold which eventually is dotted with black sclerotia in the field or storage (Figure 8 and Figure 9). Pale grey-bleached spots, stem-rot, stunting and premature death may occur in fields of canola, beginning during flowering, especially in dense plantings.

Because the sclerotia persist in soil and the choice of resistant crops is limited, short-term crop rotation is not an effective control measure. At least three years of non-host crops (cereals, corn, grasses, onions) are required to reduce the probability of problems due to the fungus. Do not plant canola near or in fields of canola, beans, peas, soybeans, sunflowers, or other crops which had a history of white mold. Use only seed free of small sclerotia - only spiral cleaners can remove such sclerotia.

Downy mildew

Downy mildew, caused by Peronospora parasitica, may be a serious foliar disease of all cruciferous crops. Susceptible hosts include canola, cabbage, broccoli, Brussels sprouts, kale, cauliflower, rutabaga, radish, horseradish, Chinese cabbage and mustards, ornamentals such as stock, wallflower, and aubretia, and many cruciferous weeds. However, there are several pathogenic varieties (physiologic races) of the fungus which attack different groups of, but not all the aforementioned, cruciferous hosts.

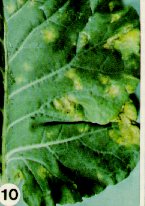

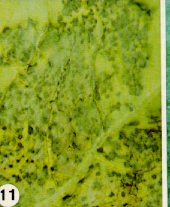

Overwintering mainly in crop debris, on cruciferous weeds, and occasionally on crop seed, downy mildew fungus becomes a problem in early spring, late summer, and fall during damp, cool weather. Beginning with lower leaves, small yellow-brown spots appear (Figure 10) which eventually expand and develop greyishblack lace-like markings (Figure 11). In moist weather, bluish-white downy mold is apparent on the underside of these leaf spots (Figure 12). Abundant sporulation and rapid disease development occur at greater than 98% relative humidity, when leaves are wet, and at 8-16°C. Downy mildew becomes severe in several days under these conditions especially when plants remain wet until mid-morning. In cauliflower and broccoli, symptoms may occur as pale brown or greyish discoloration on the curd (flower), or grey to black spots and streaks on the stems below the curd. Cabbage heads in storage also may be penetrated by greyish-black discoloration, as well as becoming susceptible to secondary rot pathogens.

Some resistant varieties of broccoli and canola are available. Accurately timed fungicide sprays on vegetable crops, seed treatment, crop rotation and mustard-weed eradication are recommended control practices. Furthermore, unless all diseased crop refuse is plowed under promptly after harvest, downy mildew (and other diseases) will continue to spread into nearby crucifer plantings by wind-blown spores. Volunteer plants such as rutabagas should be destroyed, since they may harbour downy mildew as well as other diseases from year to year.

Alternaria leaf spot

In contrast to downy mildew, Alternaria leaf spots, caused by Alternaria brassicae and other related species, usually occur during warm, moist weather. Yellow-brown spots with target-like concentric rings appear on leaves (Figure 13), as well as dark brown sunken spots on heads of Brussels sprouts (Figure 14), broccoli, and cauliflower (Figure 15). These spots contain many spores which are spread by wind, rain, or on equipment and people. Spores require at least 9 hrs. of moisture to germinate and infect the plant. Older, senescing plant parts are more susceptible to infection.

Avoid overhead irrigation during head development, eradicate cruciferous weeds and practice long rotations with non-cruciferous crops. The fungus persists on crop debris and wild crucifers and on or in seed. Hot-water seed treatment will eliminate both internal infection and external infestation of seed, while fungicide seed treatment will only control spores on the seed. Provide adequate coverage with fungicides, especially in wet weather from summer until harvest.

Controlling crucifer diseases

A generalized disease control program for cruciferous crops is as follows:

A) For producing transplants or direct seeding:

- Be sure to use resistant cultivars as much as possible.

- Consult your seed catalogues, seed company representatives, and crop specialists for further information on available resistant cultivars.

- Use only new vigorous seed with high percent germination. Old, improperly stored seeds germinate more slowly, producing weak plants which are more susceptible to disease.

- Use seed which is certified free from black-rot bacteria and Phoma, and has been treated with hot water and fungicides to control seed-borne diseases. Even though hot-water seed treatment may reduce germination, simply conduct your own germination test. Calculate the percentage germination after seed treatment, and sow extra seed to supply enough plants for your needs. Canola seed treatments are listed in OMAFRA Publication 296, Field Crop Recommendations.

- Sow seed in soil which has been fumigated (seedbeds) or sterilized (greenhouse). If fumigation is uneconomical, sow seedbeds in land which has grown no crucifers for at least 2 years.

- Use only new or sterilized transplant flats and greenhouse equipment.

- Be sure seeds are not too dense, and provide optimum conditions of ventilation, watering, fertility, temperature, and light for growth (see previous section on damping-off).

- Locate field-growth seedbeels away from existing crucifer crops to avoid introduction of disease.

- Maintain weed-free seedbeds, cold frames, and greenhouses.

- Use well-timed applications of insecticides and fungicides, according to recommendations in OMAFRA Publications 363 and 296.

- Avoid run-off from land currently or previously growing a cruciferous crop, either directly, or indirectly in irrigation water.

- Inspect the seedlings regularly, removing and destroying localized infections ("hot spots") early.

- Avoid dipping plants in water or trimming them before transplanting in the field, as this can easily spread bacteria and fungi.

B) In addition, transplant or direct seed into fields which have:

- Warm, well-drained soil, with pH greater than 7.2 if club-root has been a problem.

- Adequate, balanced fertility.

- Adequate weed control in field and headlands, especially of volunteer cruciferous crops, and cruciferous weeds, such as wild mustards, shepherd's purse, pepper-grasses, wild radish (see OMAFRA Publication 505, Ontario Weeds for identification of weeds in the Mustard (Cruciferae) family).

- Not grown crucifers for at least three crops, and which does not have evidence of former cruciferous crop residue on or in the soil.

- Continued use of pesticides as necessary for insect and disease control.

- Adequate sanitation practices, such as removing infected plants if practical, incorporating diseased crop refuse promptly, burying cull piles of rutabagas or other crucifers remotely from growing areas, working in the field only when the foliage is dry, avoiding sprinkler irrigation of the diseased fields.

C) When buying transplants, insist on the following precautions in the contract:

- Written verification of seed lot # and source; dates of pulling, shipping and receipt; pest-control schedule used in the crop, and the transit conditions.

- Certification of disease-free transplants from area where transplants are inspected by regulatory authorities prior to and at pulling time, for example, transplants from southern USA should have certification.

- Written statement that transplants were not "topped" with mowing machinery which could spread disease, and that only new packaging material was used.

By using the above management tools appropriately, disease problems in cruciferous crops can be minimized. For further information, consult the book, Diseases and Pests of Vegetable Crops in Canada, ISBN 0-9691627-3-1, the OMAFRA publication, Integrated Pest Management for Crucifers in Ontario, Order No. 701, or an OMAFRA Vegetable Specialist.