Fusarium stem and fruit rot of greenhouse pepper

Learn the symptoms, disease cycle, control, cultural practices and prevention for fusarium stem and fruit rot of greenhouse peppers.

Introduction

This disease was reported from pepper in commercial greenhouses in Ontario and British Columbia, Canada in 1991. Losses in fruit yield and plants were approximately 5%. Fusarium solani can attack a wide variety of plants including most greenhouse vegetables. Many physiologic races adapted to specific hosts have been recognized.

Symptoms

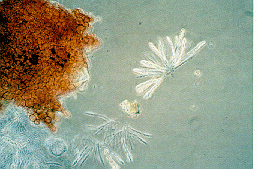

Soft, dark brown or black cankers are formed on the stem, usually at nodes or wound sites (Figure 1). These may girdle the stem in later stages of disease development. There is a dark brown discolouration of the internal portion of the stem that may extend a considerable distance (Figure 2). The lesions may eventually develop cinnamon or light orange-coloured, very small (<1 mm diameter), flask-shaped fruiting structures known as perithecia, which are the fruiting bodies of the fungus (Figure 3).

Salmon-white cottony-like growth representing the imperfect stage of the fungus and known as fungus mycelium may also be present on the surface of stem cankers in late stages of disease development (Figure 4). Stem cankers restrict the upward flow of water resulting in wilting (Figure 5) and death of the plant. Pepper fruits may also develop black, water-soaked lesions beginning around the calyx (Figure 6). The lesions grow, coalesce and spread down the sides of the fruit. Copious mycelial growth of the pathogen occurs under humid conditions particularly when temperatures exceed 25°C. The leaves of affected plants may appear mottled, similar to magnesium deficiency. Early stem symptoms of this disease are very similar to symptoms incited by Erwinia carotovora subspecies carotovora which causes bacterial stem and peduncle canker in pepper (Figures 7, 8).

Disease cycle and environmental conditions

There are 2 stages in the growth cycle of the fungus and both of these occur concurrently on pepper stem/crown tissues. The perfect stage (Nectria haematococca) is where sexual recombination occurs and fungus spores, called ascospores, are produced in the cinnamon-coloured perithecium (Figure 9). This flask-shaped fruiting structure will arise during later stages of disease development on the stem under conditions of high humidity. Research from British Columbia found that the spores are forcibly ejected about 1-2 m from the perithecium at night. This is the primary means of natural dissemination in British Columbia greenhouses. Spore release at night is more favourable for disease development since periods of high relative humidity and even dew occur during this time. The other spores, called conidia, are produced asexually and in large numbers during the imperfect stage (Fusarium solani) They are not ejected but transmitted passively, and therefore are not as important in the natural dissemination in the greenhouse. These spores may be dispersed by water splash, on pruning knives and other tools, on clothing or on workers' hands.

The ascospore germination occurs during prolonged periods of high humidity (ie. greater than 95%). Greenhouse experiments indicate that periods with relative humidity greater than 90% in the greenhouse are actually higher at the leaf surface and therefore favour Nectria haematococca ascospore germination. Rapid or late (after the sunrise) temperature increase in the morning can result in dew formation and good conditions for ascospore germination because the dew point temperature exceeds the fruit and stem temperature. A slow temperature increase early in the morning of 1°C per hour ensures that fruit and stem temperatures reach daytime targets before sunrise. Also, if the greenhouse has restricted ventilation and poor drainage, this may create a "wet" climate that N. haematococca can exploit for ascospore germination. Perithecia present on rockwool blocks and on fruit lesions provide further aerial inoculum which, when accompanied by a "wet" greenhouse climate, result in numerous fruit and stem infections. Other factors, such as over-watering of the rockwool blocks, can stress the plants through oxygen depletion, resulting in a high incidence of crown lesions. Therefore, aggressive greenhouse climate management which avoids extended periods of high relative humidity, and precisely adjusted drip irrigation that avoids excessive wetness of the rockwool blocks, may reduce disease incidence even if the fungus is present on the blocks from the beginning of the growing season.

Ascospores on plant surfaces may survive several days under unfavourable climate conditions until free moisture or a nearly saturated environment is available for infection. However, the spores will not survive a crop-free period of 3-6 weeks. Hot days with fluctuating relative humidity are detrimental for ascospore survival.

Fusarium solani is extremely common in soils of Canada and is a saprohytic fungus, which means it can colonize dead or dying plant tissues. It can produce certain overwintering spores called chlamydospores that may remain viable for years. The fungus can invade pepper stems at the nodes or at the soil line, taking advantage of wounds created by pruning or salt damage. Rapidly growing, succulent crops are the most susceptible, as are ripening fruit compared to green fruit. Fruit that is damaged, especially around the calyx, is very susceptible to infection and rotting can continue in storage. Healthy, undamaged fruit is not usually attacked. The fungus may colonize fallen or aborted fruit and senescent flowers.

Growers in British Columbia have noted the occurrence of fruiting bodies of the fungus on rockwool blocks that are introduced into the greenhouse after the propagation process and during the early part of the growth stage of the plant. The rockwool blocks may allow the fungus to survive periods of unfavourable climate in the greenhouse throughout the growing season. When conditions are favourable for spore release and infection of the pepper plants then the ascospores could be released from the fruiting structures on the rockwool blocks. Since the rockwool blocks are constantly moist, this creates ideal conditions for release of spores even if the greenhouse climate may not be as favourable.

The pathogen can also be introduced accidentally via tools and equipment carrying diseased debris from adjacent greenhouses. Workers can transfer spores via their shoes and clothes when moving from a diseased area to an area free of disease symptoms or to another greenhouse.

Infection without symptom development (latent infection) may occur on crown tissue with symptom development evident as much as 2 to 3 months later or at the end of the season. Symptom development will be triggered by plant stress arising from a heavy fruit load, adverse environmental conditions, or senescence.

Control

Include cultural practices, prevention, sanitation, environmental, and biological control measures in an integrated disease management program in the greenhouse for this problem.

Cultural practices

- Do not allow rockwool blocks to dry out at the top because damaging levels of evaporated fertilizer salts may accumulate around the stem base and thus favour infection.

- Avoid dripping fertilizer solution at the stem base by positioning the dripper away from the stem base.

- Avoid excessively high fertilizer concentrations that contribute to salt damage.

- Avoid overlap of crop production since the airborne spores of Nectria haematococca could be spread from the old crop to the early seeded peppers.

Prevention

- Carefully check rockwool blocks for presence of fungus mycelium or fungal fruiting bodies to ensure that fungus inoculum is not introduced into the greenhouse. Early detection of the disease increases the chances of eradication.

- Check transplants carefully for symptoms such as wilting or stem lesions.

- Use only plants that appear to be healthy as transplants.

- Bring suspect plants to an expert or plant disease clinic for diagnosis since early stem symptoms often resemble those caused by Erwinia carotovora subspecies carotovora, a bacterial disease of pepper.

- Ensure all workers are aware of the disease symptoms and that they are instructed to alert the management at the first sign of these symptoms.

- Identify diseased plants with coloured tape to alert workers.

- Make sure workers are aware of the spread of spores if they touch the affected stems or growing media of affected plants with their hands or clothing.

- Work in the affected areas of a greenhouse last, after working in the areas where the disease has not been observed.

- Do not move carts and crates from infected to non-infected areas. Keep visitors out of affected areas.

Sanitation

Media

- Discard slabs, bags, cubes or other media that had infected plants growing in them previously.

- Do not replant into the same material unless it has been steam-sterilized.

- Remove and discard strings that may harbour spores from affected plants.

- If the crop was grown in soil, disinfect the beds.

- Discard soilless growing media far away from the greenhouse or bury it.

Plants/plant debris

Good crop hygiene and pruning by clean cutting will help to control this disease. Because the fungus has a saprophytic stage, it may easily colonize dead fruit, flowers or leaves and later form fruiting bodies that sporulate on this colonized tissue. Therefore, it is very important to remove pepper debris from greenhouse alleyways if the disease has been observed in the particular greenhouse.

- Avoid handling diseased plants and fruit.

- Remove them from the greenhouse carefully, taking care not to allow contact of affected portions of plants with adjacent plants, and place them in a plastic bag.

- Discard the diseased material at a location away from the greenhouses to ensure that this fungus inoculum or subsequent overwintering spore inoculum is not carried back into the greenhouses by workers, wind, on tires, and by insects such as shore flies and fungus gnats. Additionally, remove about 1-2 plants on either side of the plant(s) exhibiting symptoms and place in garbage bags.

- If the material is disposed of in a cull pile then ensure that the cull pile is located away from the greenhouse as far as possible.

- Cover the cull pile to prevent insects such as shore flies and fungus gnats from carrying the fungus spores back into the greenhouses.

- Alternatively, infected plant debris may be burnt or taken to a landfill.

- Do not leave it in an open field or incorporate it into the soil in fields where other susceptible crops may be grown. The fungus has a wide host range and can produce overwintering spores that remain viable for years.

- If the disease is severe, pick the fruit at the green stage.

General disinfection

- At the end of the growing season, thoroughly clean and disinfect greenhouses.

- Maintain foot baths with adequate fresh disinfectant at every entrance to the greenhouse.

- Sanitize pruning tools used to handle infected plants by dipping in the disinfectant after each contact with the affected plant.

- After leaving the affected areas, workers, particularly those who come in contact with diseased plant material should discard disposable gloves and boots in a proper manner, leave shoes/boots for disinfection, and leave coveralls for laundering and disinfection.

- Either replace, or clean drip lines and drip stakes of affected plants by dipping in a commercial disinfectant and rinsing with water afterwards.

Environmental measures

- Avoid periods of high relative humidity (>90%), particularly at night when spore release is more favourable, by slowly increasing the temperature every hour so that fruit and stem temperatures reach daytime targets before sunrise.

- Maintain good ventilation and drainage to avoid conditions of high relative humidity that are favourable for germination of ascospores.

- Adjust drip irrigation to avoid excessive wetness of rockwool blocks to minimize conditions for ascospore release from fruiting bodies (perithecia) that may be resident on the blocks. Excessive wetness or dryness of rockwool blocks favour Fusarium stem canker for different reasons as noted earlier.

Biological

Refer to OMAFRA Publication 836: Growing Greenhouse Vegetables for biological control recommendations.