Highly vulnerable water sources

Learn about the different types of highly vulnerable water sources found on farms or rural properties. This technical information is for Ontario farmers and rural residents.

ISSN 1198-712X, Published June 2021

Introduction

All Ontarians can play a role in protecting groundwater quality and quantity. This is the fifth fact sheet of seven in a series that will help Ontario’s farmers and rural residents learn more about groundwater. This fact sheet discusses the different types of highly vulnerable water sources that may be found on a rural property or farm.

The OMAFRA fact sheets in the Groundwater series are:

- Understanding groundwater

- Managing the quantity of groundwater supplies

- Protecting the quality of groundwater supplies

- Private Rural Water Supplies

- Highly vulnerable water sources

- Disinfecting private water wells

- Testing and treating private water wells

Groundwater is a valuable resource for farm and rural families, farming (livestock watering, irrigation, wash water, etc.) and rural businesses, in some situations it may be the only water source. When living in a rural area, it is important to understand the different types of highly vulnerable water sources, groundwater and others, that may be found on a rural property or farm.

The terms “highly vulnerable” and “surface water” are used in a generic sense, rather than as defined under the Clean Water Act, 2006. Regardless of the source, surface water can contaminate a well.

Some groundwater sources are more vulnerable than others. These include shallow groundwater aquifers that have an inadequate depth (for example, less than 3 m (10 ft)) of protective overlying soil (Figure 1) and aquifers that are under the direct influence (direct and/or rapid movement) of surface water. Wells can also be vulnerable, including those where a defective casing allows direct entry of surface water, those located in a low area prone to ponding and/or flooding and those near or downslope of a potential contaminant source. An indicator that a well may be vulnerable to contamination is if the water quality changes seasonally or during storm events.

In Ontario, Regulation 903 (the Wells Regulation) prescribes requirements for the construction, maintenance and abandonment of private water wells. The Wells Regulation requires that the well owner must maintain the well in a way that prevents the entry of surface water and other foreign materials into the well. Proper construction and maintenance of a well will help prevent it from becoming a pathway for surface water and contaminants to reach the groundwater. If a well is no longer used, it must be properly abandoned (plugged and sealed). The requirements for construction change periodically, and it is recommended that well owners refer to the current requirements under the Wells Regulation.

Surface water sources

Consider surface water sources (such as lakes, ponds, rivers, streams and wetlands) as highly vulnerable to contamination and having questionable water quality. They have no natural protective layer to filter out microorganisms, such as bacteria, parasites and viruses, that make it unsuitable for human consumption without treatment.

Other sources that are influenced by surface water directly or indirectly, include:

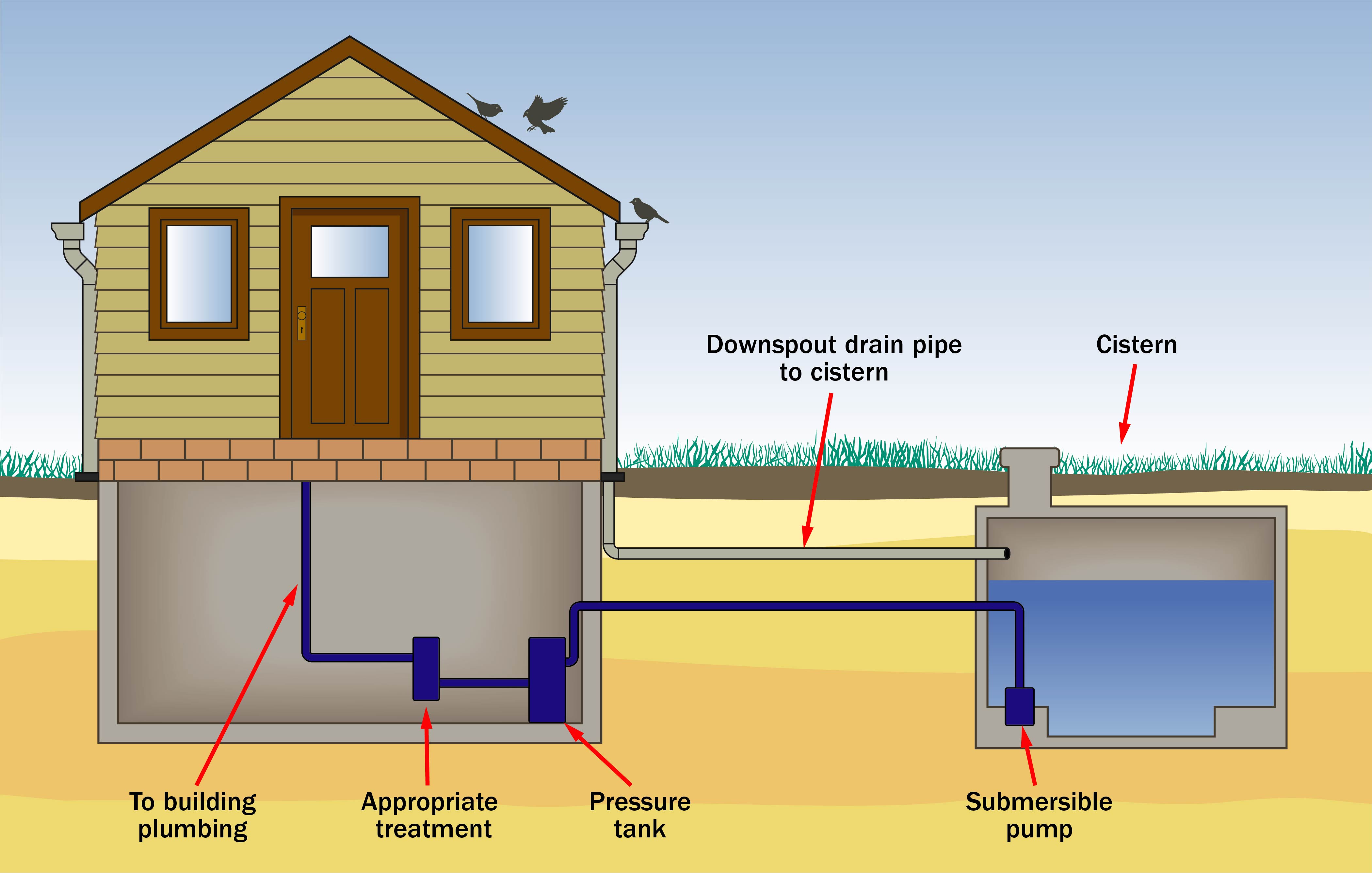

Cisterns (reservoirs used to collect and store water) are often used in areas where wells have difficulty providing an adequate quality or quantity of water. Cisterns can be contaminated with collected rainwater, by surface water seeping through cracks or when flooded (Figure 2).

Storage tanks constructed of different materials (for example, steel, plastic) are often used to meet temporary water use needs. The degree of vulnerability to contamination varies with the specific circumstances (water source, state of repair, above ground vs below ground, etc.). Use caution regarding the water quality that is available from temporary storages. Contact your local public health unit for more information.

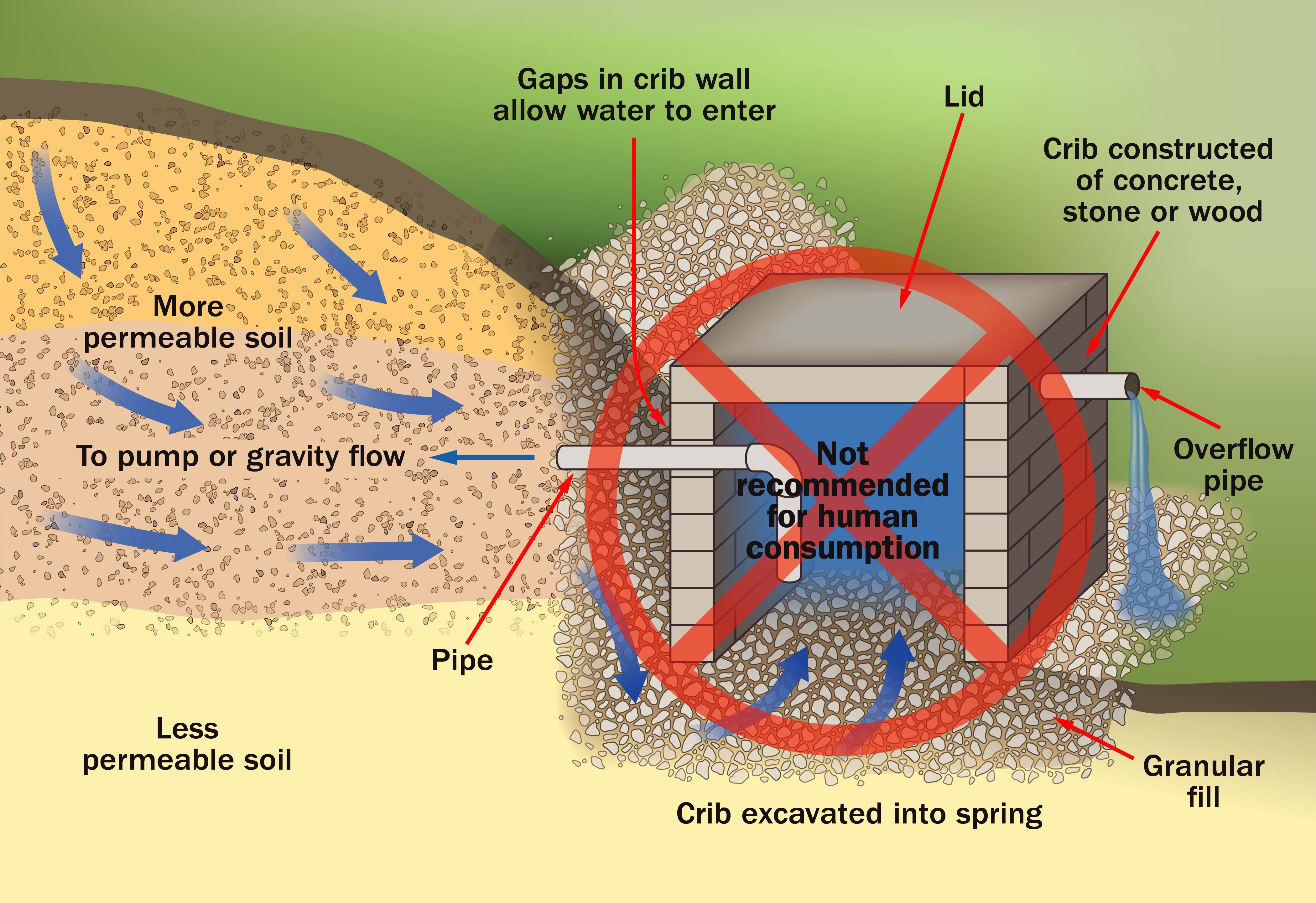

Spring boxes are constructed around a spring to collect water for more efficient pumping (Figure 3). Springs occur where groundwater flows on or near the ground surface. The source of spring water is unknown, and it is highly vulnerable to contamination from natural and human sources once it reaches the surface because the spring usually has a thin or no protective soil layer. Springs sometimes flow year-round, but many do not. A spring is not considered a well.

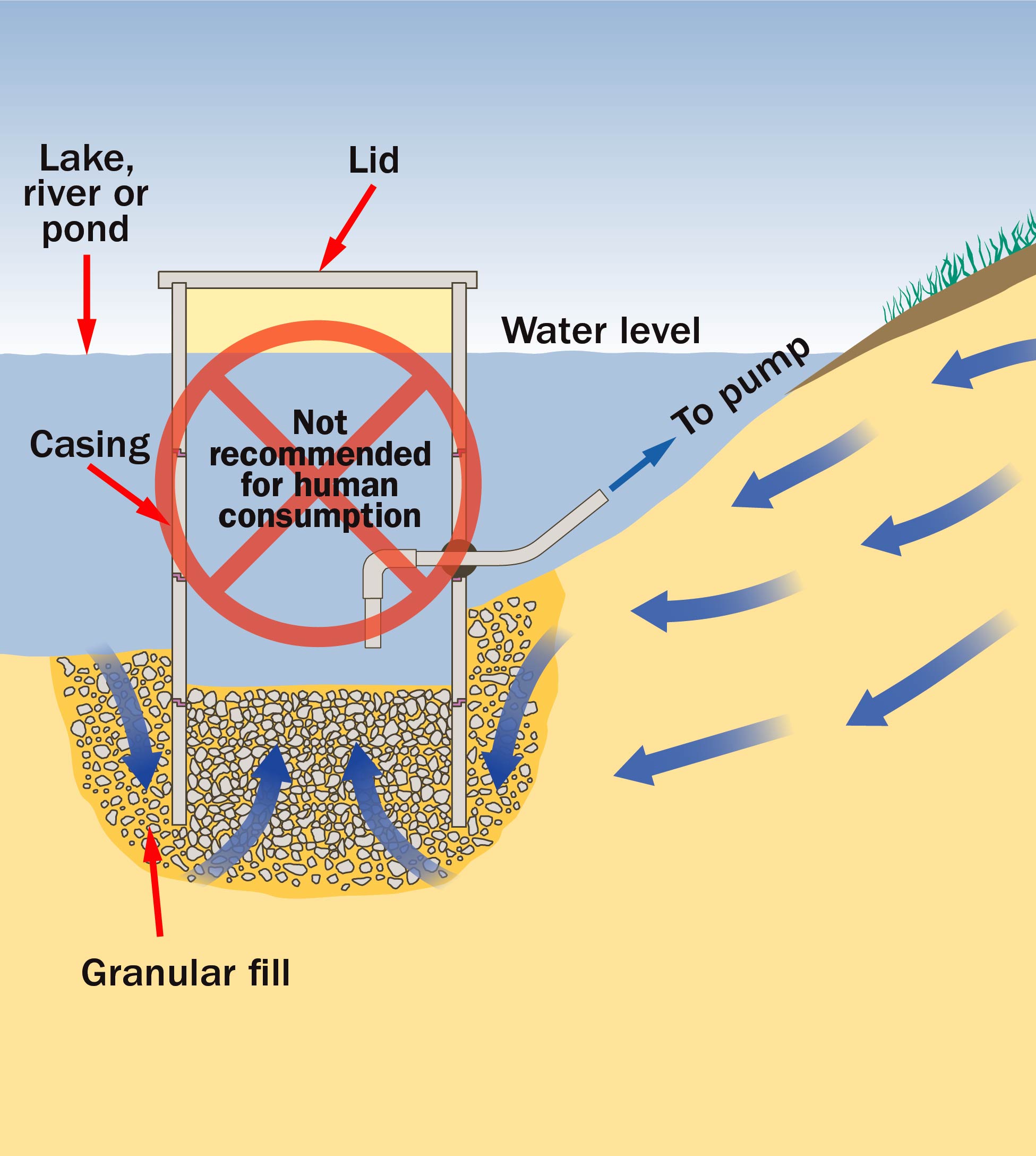

Shore wells, also known as a “surface-water trench systems” or “infiltration galleries,” are either shallow infiltration trenches filled with granular material installed near the shore of a surface water feature (for example lake, pond or stream) or structures located directly in the surface water feature near the shore. Shore wells are directly connected to and draw in surface water (Figure 4). Shore wells have a thin or no protective soil layer and are not true wells.

Groundwater sources

The risk of water quality problems with a groundwater source is directly related to the depth of soil overlying the aquifer, type of well, state of repair of the well, depth of the well and how close the well is to potential sources of contamination. The general rule is the deeper the well, the longer it will take for surface water to filter down through the overlying soil before entering the well, which increases the potential for microorganism filtering and reduces the risk of contamination. The risk of contamination also decreases as the distance between the well and potential contamination sources increases.

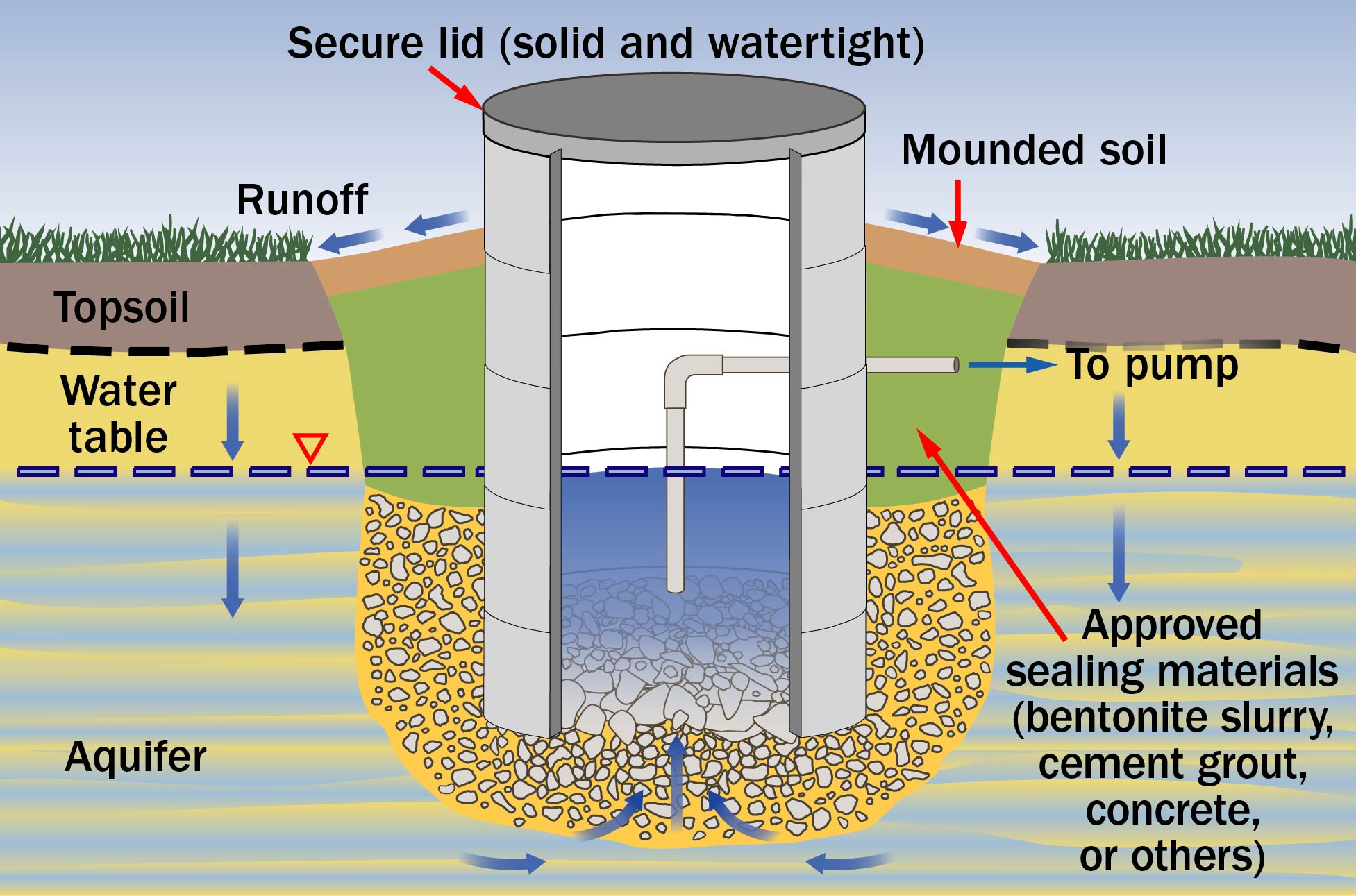

A well is designed to draw water while also keeping contaminants and surface water out. Proper well construction ensures that surface water cannot directly enter the well and will instead infiltrate and pass downward through the soil before it enters the well through the bottom (Figure 5). A well casing with proper height and a secure lid prevents direct entry of surface water, dust, debris and vermin. Mounded-up soil around the wellhead prevents ponding and directs water away from the well casing. The watertight grout (sealing material) in the space around the well casing prevents surface water from easily moving down along the side of the well casing and into the groundwater or directly into the well.

A visual above-ground inspection of a well casing can provide an indication of the state of repair below ground. If there are any concerns, contact a licensed well professional for assistance. Minimum separation distances between new wells and sources of contaminants are requirements of the Wells Regulation and the Ontario Building Code.

Vulnerable wells

Most vulnerable wells include:

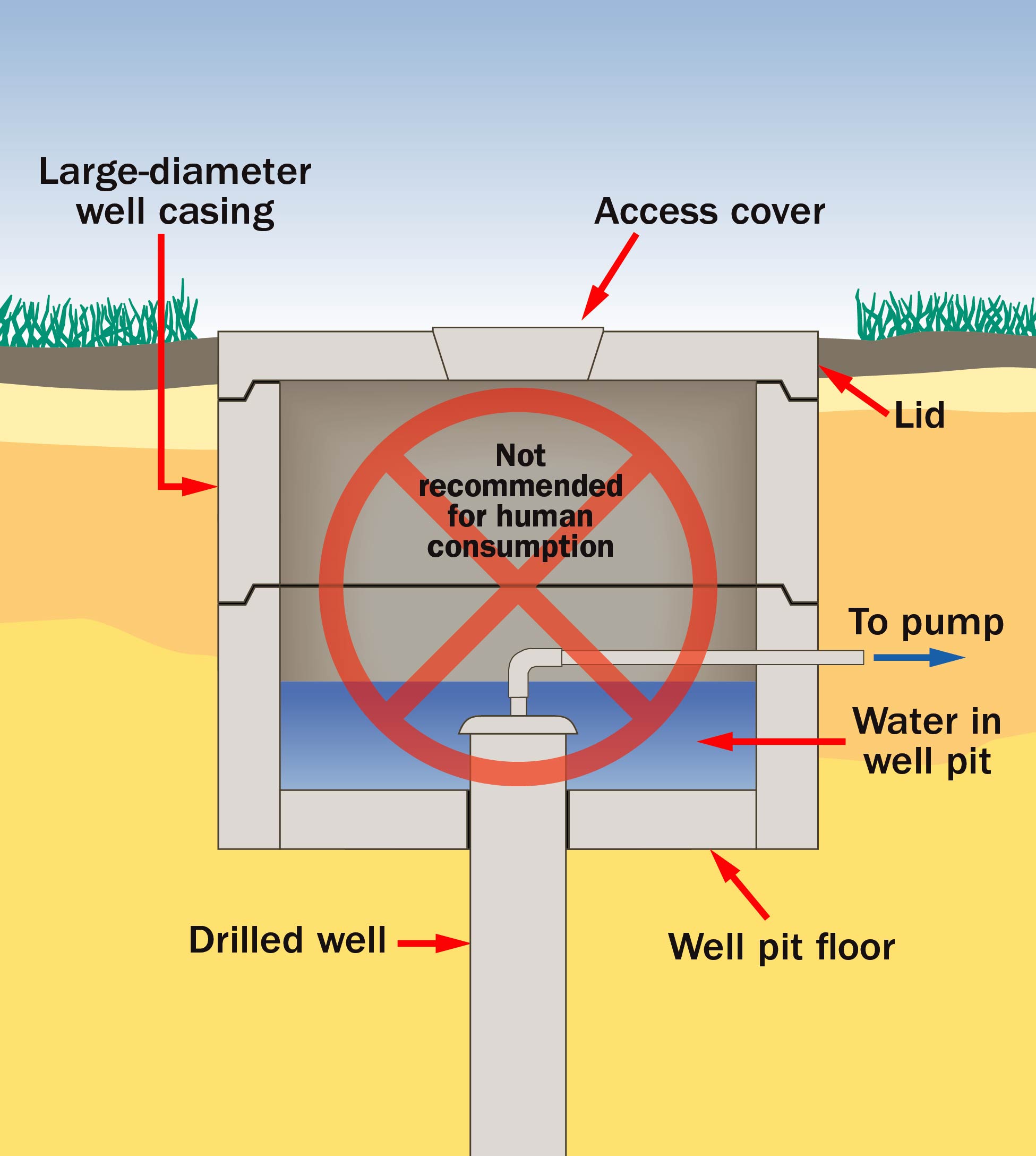

- extremely shallow or large-diameter wells (such as less than 3 m (10 ft) below ground surface)

- below-grade wells, including well pits, that are constructed where the top of the well casing is below ground level such as:

- buried wells (including those constructed beneath a structure)

- well pits (drilled wells constructed in excavations below the frost line) that are prone to flooding and not properly protected

- drilled wells constructed in old large-diameter wells (Figures 6 and 7)

The construction of well pits is no longer an acceptable practice for new wells under the Wells Regulation requirements, and existing wells with this construction should be inspected regularly and properly maintained. Table 1 shows the visual characteristics of different diameter well types.

| Well type | Description | Casing size |

|---|---|---|

| Very small-diameter | Sand-point well (if located in a shallow, sandy area) Note: Natural gas wells use similar-type casing | 2.5–5 cm (1–2 in.) |

| Small-diameter | Drilled well (most locations) Note: Natural gas wells use similar-type casing | 10–20 cm (4–8 in.) |

| Large-diameter | Often called a bored or dug well | 60–120 cm (24–48 in.) |

Do not use a highly vulnerable groundwater source unless it is the only water supply available and attempts to develop an alternative water supply have not been successful. If an alternate water supply cannot be found, the well should be:

- upgraded to meeting the requirements of the Ontario Wells Regulation

- tested regularly and found to be safe for direct consumption

- treated for potable use where it is not safe for direct consumption

When a well produces water that is not potable (such as where water tests indicate evidence of bacterial contamination), the well owner should seek advice and take steps as directed by the local public health unit as an alternative to immediately abandoning the well.

Water testing

Bacterial testing results do not give any information on the chemical or viral quality of the water supply. If you suspect there are problems with your water that are chemical or viral in nature (for example, nitrate, sulphur solvents or viruses), send a water sample to a private laboratory for testing. More information on water quality testing is provided in the OMAFRA fact sheets, Protecting the quality of groundwater supplies and Testing and treating private water wells.

The Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks provides a list of accredited laboratories that test water for specific contaminants.

More information about ways to test the water quality and options for treating the water from these ground water sources is found in the OMAFRA fact sheet, Testing and treating private water wells.

Groundwater sources can also become contaminated when the well is:

- improperly sited, designed, constructed, maintained or plugged

- constructed in a shallow fractured bedrock aquifer

- constructed in a shallow, coarse-grained overburden aquifer

- constructed in a fractured bedrock aquifer too close to an onsite sewage disposal system

- constructed using a deep bedrock borehole with a shallow casing overlain with porous soil

- contaminated by water drawn into the plumbing system through a cross-connection or by back syphoning

Plumbing cross-connections

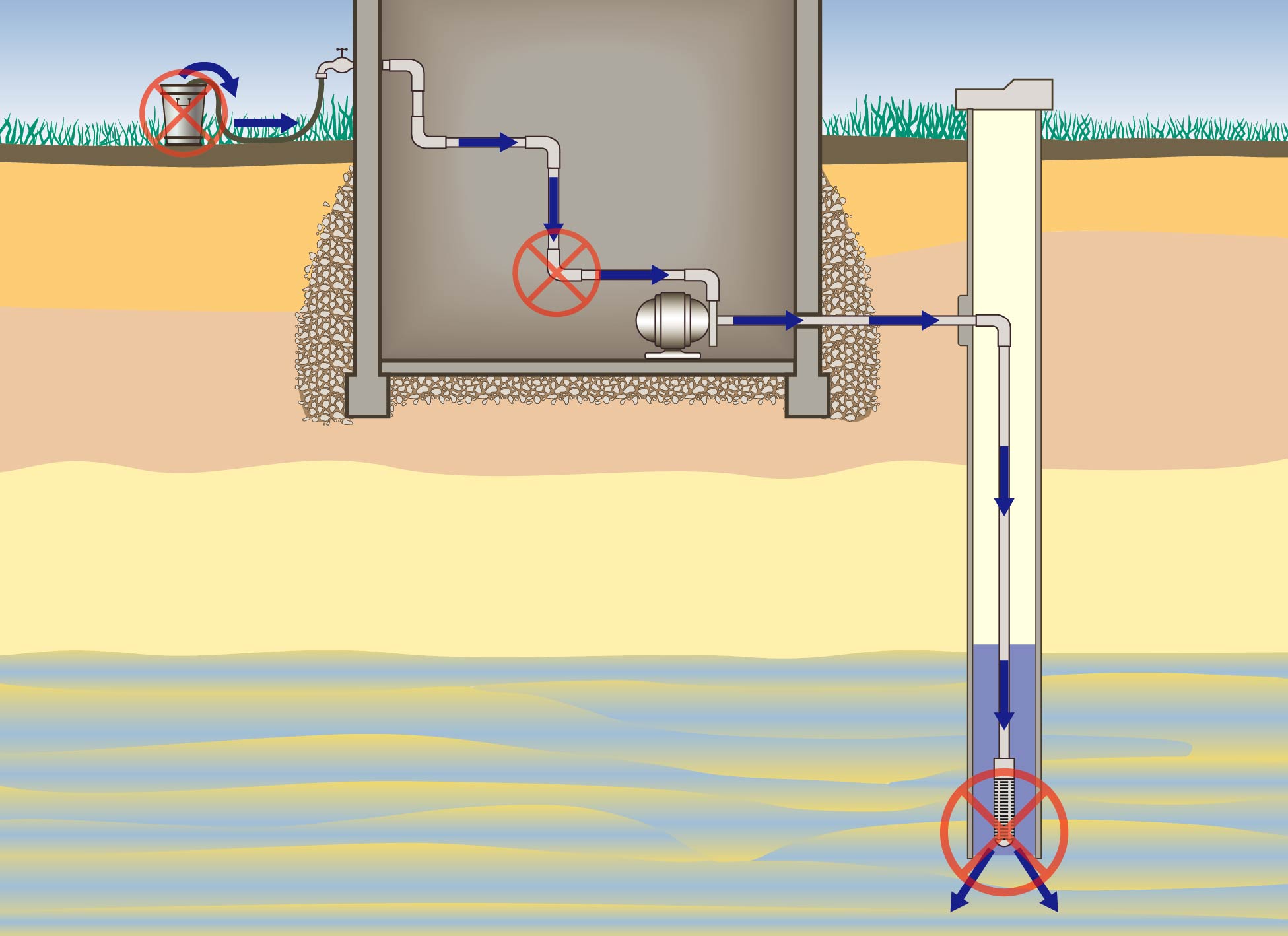

Do you know if there are any cross-connections in your plumbing system or one that may allow backflow siphoning? Plumbing cross-connections link two separate supplies of water. It’s important to know they can bring untreated, non-potable water and contaminants into the drinking water system. These cross-connections can contaminate both the well and the aquifer.

Cross-connections are not permitted under the Ontario Building Code. Make sure the drinking water system is not cross-connected with untreated, non-potable water systems. Figure 8 shows how a cross-connection between the home water system and the non-potable system can draw contaminated water into the home. From there it can drain into and contaminate both the well and aquifer.

Install a “hose bib” (external anti-backflow device or backflow preventer) on all outside taps to prevent cross-connection. If using two water wells or water sources, make sure the systems are properly separated with appropriate one-way valving to prevent water moving from one well to the other.

This fact sheet is consistent with, but does not reflect the full detail, of the Wells Regulation. For assistance with the Regulation, seek advice from the Ontario Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks (MECP) through the Wells Help Desk. Call 1-888-396-9355 or e-mail wellshelpdesk@ontario.ca.

Resources

- if you have suspected problems with your well that involve surface water, human or animal waste

- for a water sample bottle for indicator bacteria testing

- for help interpreting your water quality sample results

Public Health Ontario Laboratories:

- for a water sample bottle for indicator bacteria testing or interpretation of water sample test results

- to perform water testing in Ontario

- if you have concerns about chemicals in the well such as sulphur or nitrates

- if you are concerned that your well is improperly constructed, or requires upgrading or maintenance

- ensure they are licensed to provide this service

Ontario Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks:

Ontario Soil and Crop Association:

- Information on different actions that can be taken to protect the quality of groundwater and your drinking water supply is provided in the Canada-Ontario Environmental Farm Plan workbook and associated Infosheets.

This fact sheet was written by Dr. Hugh Simpson, program analyst (retired), OMAFRA; Jim Myslik, JPM consulting and Brewster Conant, Jr. It was reviewed by Dr. John Minnery, senior environmental science specialist, Public Health Ontario; John Warbick, engineer, crop systems & environment, OMAFRA.

Footnotes

- footnote[1] Back to paragraph Natural gas wells have used narrow casings similar to very small-diameter private water wells. More information on gas wells is found in the OMAFRA fact sheet, Locating Existing Water, Gas or Oil Wells.