Low labour feeding systems and bunk design for sheep

Learn about winter feeding set-up for the sheep flock and why a feeding set-up with flexibility is important. This technical information is for Ontario sheep producers.

ISSN 1198-712X, Published July 2014

Introduction

Flexible + low labour = profitable

This fact sheet discusses winter feeding set-up for the sheep flock and why a feeding set-up with flexibility is important.

- Feed is the single largest cost centre in the lamb production operation. Managing this cost requires that the system has flexibility in accommodating various ingredients for cost-effective rations.

- Infrastructure is a major long-term expenditure that is often larger than livestock investment and may approach land costs. Infrastructure that serves as an investment or asset should be adaptable to multiple uses, otherwise it becomes an expense that requires further investment (renovation expenses) to remain current.

- Labour is another major cost on sheep operations. The need for labour varies by animal group, time of year and rations used on farm. The feed delivery system must be flexible enough to match the available labour. When farm operators spend too much time feeding their sheep or regularly declare themselves "too busy," labour cost is too high, whether the farmers pay themselves or not. Unpaid labour has an important time cost (opportunity or personal cost), if not a cash cost.

Building a flexible feeding system

Choose a feeding system flexible enough to allow for changing the rations you use. In the OMAFRA fact sheet Feeding systems for sheep, the comparison between different feed presentations is made by animal class in Table 2, Sheep rations commonly fed over a production year and their commodity components. This table and the associated Table 3, Commodity options by concentrate feeding systems, demonstrate the nutritional "fork in the road" on how choices in the feeding system have consequences on what feed ingredients can be used.

Total mixed rations and pasture rations

The most flexible system for feed ingredient inclusion and forage type is the total mixed ration (TMR). This highly flexible and ration-optimizing technology can be used in sheep operations, as has been done successfully in dairy and beef operations. Other than pasture, no ration strategy can reduce feed costs on a per-unit dry matter basis as well as TMR.

TMRallows farm operators to target almost all classes of livestock and tweak the ingredient list used. Many bridging technologies can be used in the transition years towards TMR, if it is ever implemented. These include using large bales, bulk forages, commodity grain and byproducts and delivery by unrolling or smaller vehicles/systems - all steps that can be implemented well before investing in a mobile TMR mixer. But the fact remains that each of these bridging strategies requires good bunk design.

Reducing labour – bunk design

No amount of planning ingredients, ration presentation or forage type can succeed if delivery of the ideal feed cannot be achieved. Simple feeding systems succeed! Many feeder designs that are standard in the Ontario "lifestyle" sheep sector are inappropriate for commercial production due to either the cost per ewe per space, labour needed, inability to scale up, impacts on wool quality or poor durability. Therefore, before a sheep farm operator decides on a feeding system or an expansion of a barn or yard facility, one of the most crucial factors that must be addressed is bunk design.

Infrastructure that offers the most flexibility will allow hand feeding, mechanized feeding, loader tractors or TMR mixers access to the feed bunk and deliver simple or sophisticated rations to sheep.

The drive-by or drive-through principle is the fundamental feeding concept in barns and yards that increases the rate at which forage, in particular, can be delivered. Whether these are centre alleys, as commonly seen in new sheep barns, or fence-line feeders at yards, they have the advantage that sheep and equipment or people do not come into conflict. That is, machines don't run over sheep, and sheep don't run over people. Allowing marginally more alley width for either the "drivers" or "walkers" allows the rate of feed dispensing to be accelerated.

Generally, drive-through enabled feeders are recommended for feed ingredient flexibility, labour efficiency and ease of construction. Figure 1 shows a drive-through alley in the transition period still using dry hay and pail-feeding grain (component feeding).

One of the complaints against feed alleys that can accommodate any equipment is that they are a waste of space, based on the fact that a finished barn costs $100-$160/m2 ($10-$15/ft2) to erect. One solution to this is the H-bunk, which is available commercially as an automated bunk or can be built in place as shown in Figure 2. The name "H-bunk" comes from the shape of the cross-sectional view.

Feed alley location

Once the relationship between animal production class (for example, pregnant, lactating), bunk management, the resulting pen size and related building cost is fully appreciated, it is possible to better design a barn that meets budgetary, performance and labour needs.

For ease of feeding and labour costs, all alleys should connect in free-flowing junctions. The proven concept in other industries is to use clean H-, T- and L-shaped connections. There should be no gates or changes in level to impede feed or machinery movement or pose a safety hazard to the operator or sheep.

Manger vs. table

One of the design questions that has not been adequately addressed in the sheep industry is the concept of bunk profile. The dairy industry has moved towards feed tables in their alleys. That is, a flat, level surface continuous with the surface where feed delivery vehicles drive. The beef (feedlot) industry has moved almost exclusively to manger-type feeder designs (J-bunks). Table and manger designs are pictured in Figures 3 and 4.

Either concept can work well for specific applications but the decision to use one over the other in a ewe operation should be made considering the following points:

- bunk management style - slick bunk or ad lib

- labour - pushing up feed, cleaning, etc.

- volume fed - bulk in a ewe vs. feedlot ration

Use mangers for dry ewes fed once a day. For high-producing animals on ad-lib systems, a table would be advised. The manger approach would be best when managing fence-line-fed feedlot lambs on a limit-fed style (slick-bunk management). Of particular note is that where a manger is used, there is no cost associated with preparing a uniform alley/table floor, so overall capital cost may be reduced as well, as with the H-bunk. In this case, it is because the vehicle area can be road gravel rather than concrete.

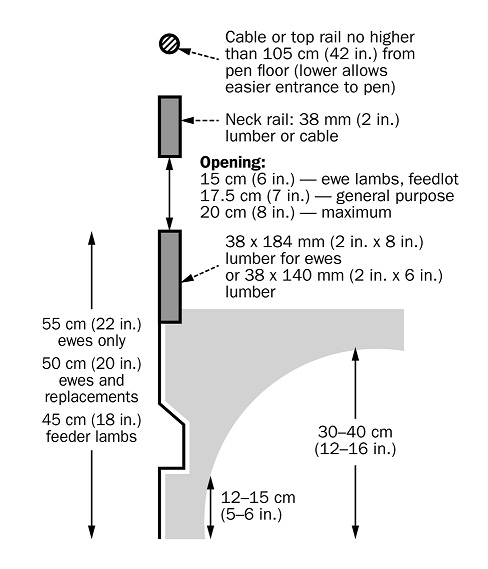

Throat height

One of the clear deficiencies in other available plans for ewe-feeding equipment is the lack of discussion on throat height - the distance from the pen floor (animals' feet) to the point over which the animal must reach in. In the design shown in Figures 5 and 6, this height is 45-50 cm (18-20 in.). The Canada Plan Service (CPS) and the Midwest Plan Service (MWPS) suggest maximum throat heights of 38 and 41 cm (15 and 16 in.), respectively, for mature ewes, but this number has been demonstrated as far too low in Ontario conditions.

When determining throat height, consider:

- manure or snow build-up in pens

- ewe size and neck length (appear larger in Ontario)

- other uses of facility (for example, lamb finishing)

Since 2010, OMAFRA's recommendation for throat height is a minimum of 45-50 cm (18-20 in.) (Figures 5 and 6), or higher with a step, which exceeds both CPS and MWPS recommendations. This recommendation still factors in 20- and 15-cm (8- and 6-in.) drops, respectively, from the throat height back down to the bunk floor.

The Quebec system has been to employ a notch in the concrete (created at pouring by adding a ridge or lumber on the form) that acts as a step to create an effective throat height that allows significant manure build-up. This has also been used effectively in Ontario for snow and manure build-up in wintering yards. The notch may also be used to accommodate young stock, such as ewe lambs or feeder lambs in a barn that can also handle ewes. This entire configuration is shown and diagrammed in Figures 5 and 6.

Preventing lamb escape

A great source of frustration in accelerated or winter lambing barns is lamb entering the feed bunk. This happens regardless of design or type. Although many approaches to this problem show success, four particular details of bunk and head-rail design appear to be helpful in prevention:

- throat height at the recommended height (not too low)

- reduced feed opening: 20 cm (8 in.) maximum, 17.5 cm (7 in.) general purpose, 15 cm (6 in.) in challenge cases

- double throat board (Quebec system) (Figure 7)

- sleeve over neck rail: 15-20 cm (6-8 in.) diameter field drainage tile over the neck rail that closes the gap when the ewe is not feeding. The tile is cut in 30-cm (12-in.) sections and slid on the rail at construction.

Putting it all together: a system

Having a profitable feeding system in tough times means that the feed ingredient options, ration specifications and delivery methodology must each have some level of affordable (labour + capital cost) flexibility. A number of design challenges have been presented in this document that interrelate with ration type, capital costs, production systems, bunk management and engineering aspects. It is strongly recommended that a sheep farm considering equipment purchases, barn renovation or expansion identify critical success (failure) factors such as those described earlier, and then let the design flow from there. This integrated set of decisions must be based on systems thinking for varying market, mechanical, capital and personal circumstances. This is what makes a flexible feeding system profitable!

This fact sheet was authored by Christoph Wand, beef cattle, sheep and goat nutritionist, OMAFRA, Guelph.