Managing Toxoplasma gondii in swine

Learn why Toxoplasma gondii is a potential food safety hazard and how to prevent infection and transmission. This technical information is for commercial swine producers in Ontario.

ISSN 1198-712X, Published June 2004

Introduction

Food safety has become a focal issue in food production and marketing worldwide. Consumers demand not only high quality foods, but also safe foods. One of the most important zoonotic (infectious to both animals and humans) parasites associated with meat is Toxoplasma gondii (T. gondii). The Canadian Quality Assurance (CQA) program has recognized T. gondii as a potential food safety hazard associated with pork. An infection caused by T. gondii is called toxoplasmosis. Traditionally, pork has been considered a major source of T. gondii for humans. However, improved housing, management and production practices have dramatically decreased the prevalence of T. gondii in Ontario's pig population, resulting in safer pork than ever before.

The spread of T. gondii

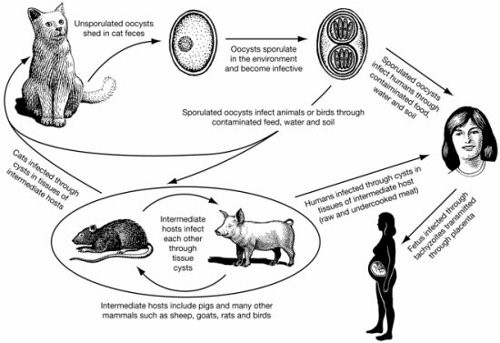

T. gondii is a tiny, single-celled (protozoan) parasite that is infectious to most warm-blooded animals, birds and humans. The organism has a complicated life cycle including two stages that are significant to the spread of the parasite: the cyst stage and the oocyst (egg) stage. Cats are the definitive hosts, meaning that the parasite is unable to complete its entire life cycle without these animals. Other animals and birds are intermediate hosts, or the carriers, of T. gondii. Newly infected cats, especially kittens, may shed millions of oocysts in their feces for a period of 3-10 days.

Once in the environment, oocysts start to sporulate (mature) and become infectious to new hosts. Infected animals will develop cysts in their muscles and organs of the body (brain, liver, heart), but do not develop or shed oocysts as cats do. Infection occurs when animals ingest either sporulated oocysts in soil, feed, water, cat feces or any other materials or cysts contained in the tissues of rodents, wildlife or other animals. For example, pigs can become infected by consuming feed or water contaminated by cat feces containing the oocysts, or by eating animal tissues such as rats or wild birds that carry the cysts.

The life cycle of T. gondii is illustrated in Figure 1.

T. gondii infection in humans

T. gondii infection is widespread in humans worldwide and reported infection rates range from 3%-70%, depending on the populations or geographic areas studied. There is limited information and very little existing data available on human T. gondii infection in Canada. However, one study involving 124 children from 38 infant-toddler daycare centres in Toronto showed approximately 13% were seropositive (antibody found in blood), indicating infection had occurred at some point. Of those serum providers born in Canada, 8.2% were seropositive. Of those born outside of Canada, 19.6% were seropositive.

Most infections of T. gondii go unnoticed. However, under certain circumstances serious illness may occur. The US Centre for Disease Control reported that T. gondii is the third leading zoonotic pathogen that can cause death after Salmonella and Listeria monocytogenes.

In infected humans, the parasite multiplies in various tissues until the body mounts immunity, then the parasite hides in tissue as cysts. The organism remains alive and if the immune system is severely impaired, the organism can break out causing further infections. Brain damage and blindness are major consequences. People with compromised immune systems due to AIDS or cancer, the elderly, very young children and fetuses are all at high risk.

The greatest concern for humans is transmission of T. gondii from mother to fetus. Women who have already been exposed to T. gondii are immune to the disease. However, in mothers who first acquire a T. gondii infection during pregnancy, about 1/3 to 1/2 of their infants are also infected. The infection could cause deformities, abortion or even stillbirth.

Infection in humans primarily occurs in four ways.

- ingestion of tissue cysts by consumption of undercooked or raw meat from infected animals

- accidental ingestion of sporulated oocysts excreted by cats through feces (touching hands to mouth after gardening, cleaning a cat's litter box, or ingesting anything contaminated with cat feces)

- transmission of T. gondii from mother to fetus (if the mother is pregnant when T. gondii infection first occurs)

- transmission of T. gondii through organ transplants or blood transfusions, although these modes are very rare

T. gondii infection in pigs

Transmission of T. gondii to pigs on the farm can occur. Ingesting anything that contains infective stages of the parasite can infect animals. It is known that a single oocyst is capable of causing an infection in pigs.

In a study of 47 farms in the U.S. state of Illinois, with typical rates of T. gondii infection (15% in sows and 2.3% in finishers), a variety of reservoir hosts were found, including: cats (68.3%), raccoons (67%), skunks (38.9%), opossums (22.7%), rats (6.7%) and mice (2.2%). In the same study, oocysts were found in samples of feed, soil and cat feces. A first-time infected cat can shed millions of oocysts each day for up to one week, and the oocysts can survive in most climates for several weeks or even years.

Infection in the Ontario pig population

Blood tests in several studies show that non-clinical (no apparent signs or symptoms) infections of T.gondii occur in Canadian pigs. Infection rates are higher in sows than market hogs, indicating that the length of exposure is a factor in acquiring T.gondii infection.

A recent serological study conducted through the province's Sentinel Herds Project showed only 35 out of the 2,520 samples tested were positive, indicating that currently the prevalence of T. gondii in Ontario's pig population appears very low (1.5%). However, the same study also found a very high prevalence on a small number of farms; almost half of the pigs tested on two farms were positive.

Toxoplasmosis in swine is a food safety issue - as opposed to an animal health issue - because T. gondii generally does not make pigs ill. Most T. gondii infections in swine are sub-clinical (no signs of infection) although the disease can cause clinical signs in pigs of all ages, especially in nursing pigs. Laboured breathing is the most common clinical sign of toxoplasmosis. Other signs include fever, general weakness, diarrhea, nervous signs, abortion and rarely, loss of vision. In some severe cases infected pigs are born dead, sick or become sick within 3 weeks of birth.

Preventing transmission of T. gondii from pork to humans

The connection between pork and human T. gondii infection has been established and documented. Control measures must be taken at the farm level and all the way through the pork chain. The consumer must also play a role in prevention of the infection by ensuring that meat is properly cooked.

Pre-slaughter (on-farm)

On-farm control is the first key step in toxoplasmosis prevention. Epidemiological data suggest that most pigs become infected after birth, either from ingesting oocysts in feed and water contaminated with infected cat feces, or by eating tissue cysts from rodents, wild animals and birds. Table 1 lists the major risk factors associated with T. gondii infection in pigs. Raising pigs that are free from T. gondii is possible if the following good production practices are followed:

- Keep cats out of the swine facilities and ensure cat feces do not contaminate feed and water. If cats are kept on the farm, a stable, mature population might be safe. Currently, vaccines for T. gondii control are not commonly available.

- Adopt an effective rodent control program to minimize mouse and rat populations.

- Tighten biosecurity programs to keep wildlife, such as birds, skunks and raccoons, from accessing pigs and facilities. Pigs raised in hoop structures or outdoors are at high risk of infection due to the easy access to barns by wild animals and birds.

- Never feed edible residual material (ERM) containing meat products. The feeding of this class of ERM to pigs is prohibited (illegal) in Canada.

- Remove dead pigs immediately to prevent cannibalism.

- Change or thoroughly wash boots before entering barns to avoid tracking in oocysts that have been shed by feral cats in the environment surrounding the barns.

Ensure proper procedures for any on-farm composting of dead pigs to ensure the activity does not attract cats or rodents. See the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA) factsheet On-farm bin composting of deadstock.

| Risk factor | Example |

|---|---|

| cats (feed, water and environment contaminated with cat feces) | access of cats to barns, feed storage, water sources and bedding |

| dead pigs | consumption of infected dead pigs |

| rodents and other wildlife | consumption of infected dead mice and rats |

| raw or under-cooked meat scraps | household scraps and restaurant wastes fed to pigs. (it is illegal to feed these materials to pigs) |

Post-slaughter

Proper cooking and freezing can easily kill T. gondii in meat. Pork should be cooked to 71°C. Freezing meat at temperatures of -18°C or lower inactivates cysts present in pork. Freezing meat in domestic freezers for 24 hours generally renders meat safe.

Summary

Infections of pigs with T. gondii have continued to drop in the last 2-3 decades due to changes made in pig production and management systems. Prevalence of T. gondii is very low in both Ontario and the rest of Canada. However, toxoplasmosis does still exist in both pigs and humans. To further reduce the risk of pork-related infection of toxoplasmosis in humans, livestock producers, meat packers and processors, and consumers have to take appropriate measures to control this organism. For pork producers, keeping cats out of the swine facilities and strictly following biosecurity and rodent control programs are key measures to take for effective control of T. gondii .

Sources

Dubey J.P., Weigel R. M., Siegel A.M., Thulliez P., Kitron U.D., Mitchell M. A., Mannelli A, Mateus-Pinilla N.E., Shen S. K., Kwok O. C. H. and Todd K. S. 1995. Sources and reservoirs of Toxoplasma gondii infection on 47 swine farms in Illinois. J. Parasitol 81: 723-729.

Ford-Jones E., I. Kitai, M. Corey, R. Notenboom, N. Hollander, E. Kelly, H. Akoury , G. Ryan, I. Kyle, R. Gold. 1996. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma antibody in a Toronto population. Can J Infect Dis. 7(5):326-328.

Friendship, B., J. Wu, Z. Poljak and D. Ojkic. 2003. Toxoplasmosis. 22nd Centralia Swine Research Update. PI-9

Gamble, H. R., S. Patton and L. E. Miller. 2000. Facts: Toxoplasma. National Pork Producers Council, U.S.A.

Lake, R., Hudson A. and Cressey P. 2002. Risk Profile: Toxoplasma gondii in red meat and meat products. Institute of Environmental Science & Research Limited. Christchurch Science Centre. New Zealand.

The U.S.A. Centre for Disease Control (CDC). Food-related illness and death in the United States. 1999. Emerg. Infect. Dis., 5(5) Sept.-Oct. CDC. U.S.A.

This factsheet was originally written by Wayne Du - Pork Quality Assurance Program Lead, OMAFRA.