Ontario’s Great Lakes Strategy 2016 progress report

This progress report outlines some of the key accomplishments and new scientific findings established during the first three years of Ontario’s Great Lakes Strategy. It represents the actions across 14 different Great Lakes ministries and numerous partners, including First Nation and Métis communities, municipalities, conservation authorities, environmental organizations, the science community, and the industrial, agricultural, recreational and tourism sectors.

Message from the Minister

On behalf of all of Ontario’s Great Lakes ministers, I am pleased to present this first Great Lakes Strategy progress report.

The Great Lakes are vitally important to the people of Ontario for our drinking water, quality of life and prosperity.

The Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River watersheds hold nearly one-fifth of all the fresh surface water on the planet. For Ontario, this global ecosystem is both a tremendous gift, and a great responsibility.

We rely on this remarkable system of lakes for the water we drink, for the energy that powers our communities, for industry and for moving goods to market. With over 98% of Ontarians now living in the watersheds of the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River, these watersheds also give most of us our beaches, our waterfronts, our nature experiences and the places we call home.

When we released Ontario’s Great Lakes Strategy in 2012, we set out priority actions that the Government of Ontario, working with partners, would take to help keep the Great Lakes drinkable, swimmable and fishable for generations to come. Ontario’s Great Lakes Strategy included a commitment to reporting on progress after three years.

This progress report outlines some of the key accomplishments and new scientific findings during the first three years of Ontario’s Great Lakes Strategy. It represents the efforts across 14 different ministries and numerous partners.

Together, with our many Great Lakes partners, we are working to protect water, restore nature and focus efforts on priority geographic areas such as wetlands. We have been able to learn from and work with First Nations in implementing Ontario’s Great Lakes Strategy. We are helping Ontarians connect with and benefit from these majestic lakes. But there is still more work to be done. We need to continue to invest in science and monitoring of our Great Lakes waters to better inform us of threats to the lakes. We will use this science to ensure we are making informed decisions to better protect and improve the quality of the lakes.

New scientific research over the past few years also underscores the vulnerability of our Great Lakes. For example, in the summer of 2015 Lake Erie experienced its biggest harmful algal bloom ever recorded. This report shares some recent science on the causes of Lake Erie’s water quality issues and on other pressing issues such as the impacts of climate change in the Great Lakes.

In October of 2015, the Ontario Legislature passed a new law, the Great Lakes Protection Act. This act recognizes the diverse issues facing the Great Lakes, from invasive species to pollution to climate change. It provides new tools to better tackle these challenges.

The act enshrines Ontario’s Great Lakes Strategy as a living document and ensures that Great Lakes progress reports will be released every three years.

Healthy Great Lakes are essential to the success of our province. We need to work with all our partners to increase our efforts to protect and restore the Great Lakes. Only by working together can we ensure that our children will inherit a legacy of a healthy and resilient Great Lakes ecosystem.

I encourage all Ontarians to read this report and to get involved in protecting our Great Lakes.

Glen Murray

Minister of the Environment and Climate Change

Introduction

Lake Superior, Lake Huron, Lake Erie, Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River — nearly everyone who lives, works or travels in Ontario, knows at least one of these magnificent bodies of water, their watersheds and connecting rivers. In fact, whenever you catch a fish, bike along a trail, visit a provincial park, turn on the faucet to get a drink of water or enjoy a glass of wine from an Ontario vineyard, chances are you are enjoying the benefits of the Great Lakes. We have the world’s longest freshwater coastline − and more of the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River’s water and coastline than all of the U.S. Great Lakes States combined.

The Province developed Ontario’s Great Lakes Strategy in response to new pressures that were putting the Great Lakes in jeopardy. Scientists who study the Great Lakes were warning us that the lakes were at “a tipping point” of irreversible decline. Our commitments in Ontario’s Great Lakes Strategy included a promise to report back to Ontarians in three years on our success in carrying out the Strategy as part of our shared responsibility to protect the Great Lakes.

In this report you will find highlights of Ontario’s Great Lakes achievements organized around the six goals of the Strategy:

- Goal 1: Engaging and empowering communities

- Goal 2: Protecting water for human and ecological health

- Goal 3: Improving wetlands, beaches and coastal areas

- Goal 4: Protecting habitats and species

- Goal 5: Enhancing understanding and adaptation

- Goal 6: Ensuring environmentally sustainable economic opportunities and innovation

The report spotlights developments in Great Lakes science, as well as some measures we are using to track our progress. Throughout the report you will find links to comprehensive resources about the Great Lakes, including detailed Ontario and binational technical reports on the health of the Great Lakes, their water quality and biodiversity.

This first progress report represents actions and efforts across the 14 Great Lakes ministries led by the Ministries of: Environment and Climate Change; Natural Resources and Forestry; Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs; Municipal Affairs and Housing; Economic Development, Employment and Infrastructure; Aboriginal Affairs; Tourism, Culture and Sport; Health and Long-Term Care; Transportation; and Intergovernmental Affairs. Input has been provided by the Ministries of Education, Energy, Research and Innovation, and Northern Development and Mines. The report also represents some key actions of First Nations and Métis communities, municipalities, conservation authorities and watershed groups, environmental organizations, the scientific community and academia, the industrial, agricultural, recreational and tourism sectors and the general public.

We recognise that the Great Lakes are a shared system. Ontario’s partnerships with Canada and neighbouring jurisdictions are essential to achieving resilience for the Great Lakes. Ontario also recognises that with so much of the Great Lakes system within our province, we have a responsibility to take action to protect these shared waters. Although this report describes many positive developments since the release of the 2012 Strategy, it also contains recent scientific findings that remind us of the stress these lakes are under. More needs to be done to restore and protect the Great Lakes ecosystem.

We thank all of the organizations and individuals who have contributed to the progress and successes that this report describes.

The Great Lakes – the foundation of Ontario’s economy and quality of life

The Great Lakes are a source of enormous economic benefit to Ontario and the foundation of Ontario’s growth and development. They are vital to our well-being and provide invaluable amenities and services. The Great Lakes and their watersheds:

- generate 80% of Ontario power (hydro and cooling)

- provide recreational fishing opportunities to about 385,000 anglers whose total direct expenditures and investments wholly attributable to recreational fishing in the Great lakes are about $432 million annually

- are home to over 95% of Ontario’s agriculture and food production

- provide a navigable seaway to support base industries that depend on marine transport including the steel, construction, agriculture, energy and chemical industries

- provide sources of drinking water for a majority of Ontarians

Ontario’s new Great Lakes Protection Act, 2015

On November 3, 2015, Ontario’s Great Lakes Protection Act, 2015, received Royal Assent. This new law reflects the goals and principles of Ontario’s Great Lakes Strategy and enshrines it in law, setting out detailed requirements for Strategy contents, reporting and periodic review.

The act is designed to help address the significant environmental challenges facing the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River Basin, including the changing climate. It identifies some initial priorities for immediate action, such as reducing harmful algal blooms. At the same time, this legislation enables public bodies to identify and target actions on priority issues and geographic areas. It provides new tools, including:

- establishing a Great Lakes Guardians' Council, a forum to help improve collaboration among Ontario’s Great Lakes partners

- the authority to set Great Lakes targets along with action plans

- enabling communities and governments to focus actions on local or regional problems through plans known as “geographically-focused initiatives”

- establishing or maintaining monitoring programs on key ecological conditions

This document fulfills the commitment in Ontario’s Great Lakes Strategy to report back after three years of the release of the Strategy. Our next progress report will deliver on Section 8 of the act’s detailed reporting requirements. In addition to reporting our progress we will provide details about a suite of environmental monitoring programs and include information on targets set. Under the act we have also committed to launching a review of Ontario’s Great Lakes Strategy by December 2018 and every six years thereafter.

Great Lakes Protection Act, 2015.

Goal 1: Engaging and empowering communities

Measuring progress on local community action

Since 2012, the Great Lakes Guardian Community Fund (GLGCF) has awarded $4.5 million to 221 projects, while partners have contributed over $15.8 million in support. It is our target to see continued increases in these figures as more individuals and communities become involved in the protection and restoration of the Great Lakes.

GLGCF project achievements include:

- engaging over 11,000 volunteers

- planting 85,125 trees (trees, shrubs and plants)

- releasing 2,133 fish

- collecting 586 bags of garbage

The high level of participation in GLGCF projects shows Ontarians are connecting with their Great Lakes and taking action to make a difference.

Local community action programs

Through hands-on activities, communities are taking action to protect the Great Lakes. In 2012 the Great Lakes Guardian Community Fund (GLGCF) was established, providing grants to not-for-profit organizations and First Nations and Métis communities to support projects with benefits to the Great Lakes and their connecting rivers and watersheds. For example:

- the Ontario Federation of Anglers and Hunters are helping to eradicate the water soldier - an aquatic invasive plant species - from the Trent Severn Waterway (the waterway which connects Lake Ontario and Lake Huron). Using a mechanical harvester approximately 192 cubic yards of water soldier was removed from the waters.

- Environmental Defence is a non-profit organization working with the community to create "The Living Beach," a rain garden project at Woodbine Beach in Toronto on Lake Ontario. Beach visitors will experience a rich and diverse natural habitat in an urban centre. The project also includes workshops to teach the benefits of creating home rain gardens (gardens that take advantage of rainfall and reduce stormwater runoff).

Building awareness

Ontario Parks and its partners offer programs that help people of all ages connect with the natural and cultural history of the Great Lakes. Each summer over half a million park visitors take part in over 9,000 staff-led natural heritage education programs. Millions more learn about Ontario’s natural and cultural heritage through museums, educational signage, publications and social media. Ontario offers a Learn to Camp and a Learn to Fish program at dozens of provincial parks and outdoor areas in Ontario. These programs introduce thousands of Canadians (often new Canadians) to camping and fishing experiences in a safe, fun and encouraging environment. The programs are consistent with the vision and principles of the Ontario Children’s Outdoor Charter. The Charter aims to get children outside to discover nature’s wonders.

Since the release of the Strategy, Ontario has been working with elementary and high school teachers to provide opportunities to use the Great Lakes and their watersheds as context for teaching and learning. In 2015, Ontario supported the Children’s Water Education Council in creating a new Great Lakes Activity Centre for the Children’s Water Festival. Twenty-eight festivals were held across Ontario with 60,000 student participants.

Ontario has supported new Great Lakes content for a one-of-a-kind program called EcoSchools. EcoSchools is an environmental education and certification program for students in kindergarten to Grade 12.

Ontario worked with local conservation authorities and other environmental partners to support teachers and school boards in creating Great Lakes learning opportunities. The result was a series of conferences for Grade 11–12 Specialist High Skills Major teachers and students across the Great Lakes Basin. More than 500 students met with Great Lakes professionals and took part in lakeside hands-on activities. More conferences are scheduled for 2016 due to the enthusiastic response from teachers, students and Great Lakes professionals. Ontario’s work has supported school boards, conservation authorities and other Great Lakes partners in forging relationships that will help build greater Great Lakes awareness and provide students with community-connected experiential learning opportunities.

Ontario’s conservation authorities: Protecting the Great Lakes watershed

In 2013, Conservation Ontario developed an interactive online Great Lakes watershed map that lets users identify their watershed and its connection to its Great Lake. The map showcases Great Lakes watershed features and functions, the water cycle, benefits of the Great Lakes, stressors on the lakes, and actions and activities taking place to help the lakes.

Measuring progress on building awareness

To support our efforts to build Ontarians’ Great Lakes awareness, Ontario assesses the number of participants in Ontario Parks natural heritage programs and the number of teachers engaged through Ontario’s Great Lakes initiatives. Each summer, 2.8 million park visitors take part in Ontario Parks education programs. Since the launch of the Strategy, approximately 2000 teachers have been engaged by Ontario’s Great Lakes initiatives.

Collaboration and partnerships

Ontario’s cultural institutions attract millions of visitors each year. They help to educate and engage visitors through experiences that deepen their connection to the Great Lakes. For example:

- The Toronto Zoo established the Toronto Zoo Great Lakes program in 2014 which provides students and teachers across seven school boards with resources that incorporate the Great Lakes into lesson plans and learning activities.

- The Ontario Science Centre is exploring a plan to redevelop the Great Lakes exhibit to make it more interactive and accessible to a wide range of visitors.

- The Royal Ontario Museum is a member of the Ontario Biodiversity Council and the Biodiversity Education and Awareness Network, helping to achieve the goals of Ontario’s Biodiversity Strategy. The museum supports biodiversity education and awareness including the development and distribution of curriculum-based lesson plans and other resources about the diversity of living things.

Investing in the Great Lakes

In addition to the base funding for core programs across all ministries, Ontario invests an additional $15 million annually toward projects that directly benefit the Great Lakes. Since 2007, Ontario has invested more than $140 million into 1,000 local Great Lakes protection projects that have reduced harmful pollutants, restored some of the most contaminated areas and engaged hundreds of partners and community groups to protect and restore the health of the Great Lakes. Since 2007, Ontario has also invested more than $660 million in upgrades to municipal wastewater and stormwater infrastructure in the Great Lakes Basin.

Engaging social scientists on the future of the Great Lakes

In 2015, the Great Lakes Futures Project was completed and featured in a special issue of the Journal of Great Lakes Research. The project engaged Great Lakes experts across many sectors, and 21 Ontario and U.S. research organizations and universities. The project identified driving forces that influence the air, watershed and water bodies of the Great Lakes region. Researchers examined these drivers of change and generated four potential future scenarios for the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Basin. Based on a structured scenario analysis and extensive stakeholder engagement, researchers proposed areas of governance and policy improvement to achieve a thriving and prosperous future for the region. The project also contributed to broadening and strengthening a network of Great Lakes experts across many sectors and regions.

Strengthening and building relationships with First Nations communities

"The Great Lakes are the heart of our Nation" Rhonda Gagnon, Anishinabek Nation

Ontario’s Great Lakes Strategy and the Great Lakes Protection Act, 2015 recognize First Nations’ relationship with the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Basin. For millennia, First Nations peoples have lived in the Great Lakes Basin – fishing, hunting, farming and trading, while maintaining a spiritual and cultural relationship with the Great Lakes.

In implementing the Strategy, we have engaged with and continued to strengthen and build relationships with First Nations communities and organizations. The act recognizes that First Nations maintain a relationship with water. The act re-affirms that it does not abrogate or derogate from the protection provided for existing Aboriginal and treaty rights. The act recognizes that First Nation may offer their traditional ecological knowledge to help carry out anything done under the act such as reviewing or amending the Strategy, establishing targets, preparing plans, deciding whether to approve a proposal for an initiative, and deciding to seek Cabinet approval of a geographically-focused initiative The act requires the Minister of the Environment and Climate Change to consider traditional ecological knowledge if offered.

Traditional ecological knowledge is already offered and considered in some provincial decisions. For example, Walpole Island First Nation was consulted on traditional ecological knowledge about species at risk affected by a new highway in the Windsor area. This knowledge has been valuable in mitigating the impacts of development on those species. Walpole Island First Nation collaborated on protection initiatives through various ecological circles (public gatherings on Walpole Island) to learn more about species at risk and their significance to the First Nation and Windsor communities. Walpole Island First Nation’s business, Danshab Enterprises, became a valuable partner with the Province in transplanting species at risk.

In early 2016, Ontario worked in partnership with Canada and the Chiefs of Ontario to host the first annual meeting with First Nations communities under the Canada-Ontario Agreement on Great Lakes Water Quality and Ecosystem Health, 2014.

Following in the footsteps of our ancestors - elders and youth gathering

Building on the success of an initial gathering in 2014, in March 2015 over 70 First Nation youth and Elders gathered in Sault Ste. Marie on the St. Marys River between Lake Huron and Lake Superior, to participate in a three-day traditional ecological knowledge gathering, “Following in the Footsteps of our Ancestors.”

The event connected youth and Elders in order to foster discussion on Great Lakes and water issues. The purpose was to provide youth with practical traditional ecological knowledge for addressing environmental concerns, empower youth with skills to get involved in their community and provide opportunities for Elders to share their knowledge with youth. The gathering opened with a traditional ceremony. A main highlight of the event was a four-kilometre water walk led by youth where they discussed hands-on, experiential learning opportunities on how to care for water.

Over the course of the three days, youth, Elders and other participants gave presentations on water and the environment. There was a strong desire to share and experience knowledge with others, as well as discuss topics such as water spills clean-up, student research, vulnerable areas and renewable energy. There were suggestions for identifying potential partnerships, networking, collaborating, sharing knowledge and empowering youth.

In early 2016, Ontario worked in partnership with Canada and the Chiefs of Ontario to host the first annual meeting with First Nation communities under the Canada-Ontario Agreement on Great Lakes Water Quality and Ecosystem Health, 2014.

Engaging Métis communities

The Great Lakes Protection Act, 2015, recognizes that the Great Lakes Basin is a historic location where Métis identity emerged in Ontario. In implementing the Strategy, we have engaged with and continued to build relationships with Métis communities and organizations in efforts to protect these waters together. Activities are underway with Métis people on the development of a pilot project to support the use of Métis traditional knowledge in contributing to understanding and addressing key Great Lakes issues.

A Great Lakes meeting with Métis people was held in early 2016 to discuss Ontario’s various Great Lakes initiatives, including the Great Lakes Protection Act, 2015 and Ontario’s Great Lakes Strategy. Ontario also partnered with Canada and the Métis Nation of Ontario to host the first annual meeting with Métis people under the Canada-Ontario Agreement on Great Lakes Water Quality and Ecosystem Health, 2014.

Renewing the Canada-Ontario commitment to the Great Lakes

In 2014, Canada and Ontario renewed their commitment to the Great Lakes by signing a new Canada-Ontario Agreement on Great Lakes Water Quality and Ecosystem Health, 2014 (COA), the eighth COA since 1971. The Ministries of the Environment and Climate Change, Natural Resources and Forestry and Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs have signed this five-year agreement, along with seven federal departments.

The new COA has provisions to strengthen governance and accountability measures. It also includes new annexes on Engaging First Nations, Engaging Métis, Engaging Communities and Climate Change Impacts.

During the term of the 2014 COA, the governments hope to complete all actions toward delisting five Areas of Concern and make significant progress in the remaining Areas of Concern; take targeted action in priority nearshore areas; increase investment in nutrients reduction research and monitoring, and climate change science; undertake more focused invasive species work; and provide a more strategic approach to influencing future water infrastructure investments.

The COA supports Canada’s commitments under the Canada-U.S. Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement. Ontario also continues to support other related binational efforts on Great Lakes protection. For example, senior Ontario staff serve as members of the International Joint Commission’s Water Quality Board and Science Advisory Board.

Focus for future action

Building on the accomplishments of Goal 1, future directions to enhance community engagement and empowerment on Great Lakes over the next few years will include:

- supporting Great Lakes workshops and the creation of Great Lakes learning guides to help educators deliver the EcoSchools program. Students will have the opportunity to engage in Great Lakes projects that affect their whole community. We will also work with school boards and conservation authorities to bring Great Lakes workshops to more high school students in Ontario.

- continuing to strengthen and build Great Lakes relationships with First Nations communities and with Métis communities. The Minister of the Environment and Climate Change will consider traditional ecological knowledge, if offered, when implementing the new Great Lakes Protection Act, 2015.

- working closely with federal agencies and other partners as we deliver Ontario’s commitments under the Canada-Ontario Agreement on Great Lakes Water Quality and Ecosystem Health, 2014.

Goal 2: Protecting water for human and ecological health

Protecting drinking water

Source protection involves protecting the surface or groundwater that supplies municipal drinking water systems. Protecting water at its source is a crucial first step in Ontario’s approach to delivering safe drinking water.

Ontario has 19 source protection regions. Fifteen of these rely on the Great Lakes and their connecting channels as a source of municipal drinking water. Each region has a local source protection committee made up of multiple stakeholders. These committees have developed science-based plans to identify and address existing and potential risks to municipal drinking water in their communities. Ontario has approved all plans across the 19 regions. Small and rural municipalities have received funding to assist in the implementation of these plans.

With all source protection plans now approved, implementation is well underway. Ontario will be working with the conservation authorities, municipalities and other stakeholders to ensure future source protection plan updates consider other potential risks facing the Great Lakes nearshore waters.

Supporting drinking water source protection within First Nations communities

Ontario has collaborated through voluntary partnerships with First Nations who choose to participate in Ontario’s drinking water source protection program.

Of the 19 Source Protection Committees, 12 have seats dedicated to First Nations representatives. Six First Nations communities have appointed members to sit on source protection committees in an observer capacity. Three First Nations communities passed band council resolutions under the Clean Water Act, 2006 to include their drinking water systems in source protection planning.

Ontario has provided support to these First Nations communities to help them implement their plans and to others who are exploring the best approach to protect on-reserve sources of drinking water. Examples include funding for:

- technical studies that have supported the inclusion of three First Nations drinking water systems – Chippewas of Rama, Six Nations of the Grand River and Chippewas of Kettle and Stony Point – in local source protection plans to help ensure actions were taken off-reserve to protect the First Nations’ drinking water sources.

- capacity-building in First Nations communities, which help them review local source protection plans and provide input.

- Chiefs of Ontario to develop guidance on how First Nations traditional ecological knowledge could be integrated into local source protection plans.

- the Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte to develop and deliver education and outreach addressing community drinking water source issues.

Making Ontario’s drinking water standards even stronger

In late 2014 and early 2015, Ontario consulted with the public on proposed amendments to Ontario’s Drinking Water Quality Standards in consideration of the advice of the Advisory Council on Drinking Water Quality and Testing Standards (Ontario Drinking Water Advisory Council), specifically:

- adding four new substances (chlorite, chlorate, MCPA and haloacetic acids)

- stronger standards for four existing substances (arsenic, carbon tetrachloride, benzene and vinyl chloride)

In December 2015 Ontario posted a decision notice on the Environmental Registry outlining the implementation of testing and reporting requirements regarding these standards. These standards and the requirements for sampling and testing for each will come into effect over the next four years.

Measuring progress on protecting drinking water

Ontario has an award-winning drinking water safety net. This is why drinking water meets high performance benchmarks: since 2012-13, 99.9% of drinking water tests from municipal residential drinking water systems that draw surface water from the Great Lakes Basin have met Ontario’s drinking water quality standards. We are committed to continuing to work with our partners to protect our drinking water.

Protecting water quality and reducing toxic chemicals

Canada and Ontario have developed an assessment report on the status of Tier I (of immediate concern) and Tier II (of potential concern) Substances in the Great Lakes Basin. Planned for release in 2016, the report is expected to present findings on toxic substances that have been a focus for joint Canada-Ontario reductions in the Great Lakes. It is also expected to contain information on the use and release of each substance into the environment, on monitoring data and environmental trends in the Great Lakes Basin and on government actions to reduce the substances in the environment.

In 2014, Ontario ended coal-fired electricity generation across the province. By promoting renewable energy sources through the Feed-In Tariff program, the Province not only reduced greenhouse gas emissions, it also reduced pollutants such as mercury. This is contributing to cleaner air and to making Great Lakes fish safer to eat. To learn more about how Ontario is encouraging greater use of renewable energy sources, visit the Power Authority website.

Through the Canada–Ontario Agreement on Great Lakes Water Quality and Ecosystem Health, 2014, the governments are committed to identifying a renewed set of Chemicals of Concern for which priority actions will be taken to reduce their presence in the Great Lakes Basin. Canada and Ontario are currently developing the first list of Chemicals of Concern which will include any substances identified as Chemicals of Mutual Concern through the Canada-U.S. Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement.

Measuring progress on reducing toxic chemicals

Two measures we are using to gauge the reduction of toxic chemicals in the Great Lakes are the concentration of contaminants such as PCBs in Great Lakes fish, and the related restrictions on fish consumption. Since the 1970s there has been a dramatic reduction in contaminants in Great Lakes. Harmful pollutants have been phased out or banned resulting in over 90% reduction levels for some contaminants. As the ecosystem recovers, contaminant levels continue to decline at most locations, with some exceptions. For example, a slight upward trend in contaminant levels in some Lake Erie fish is occurring. As we learn more about the toxicity of contaminants, our standards for fish consumption have become stricter over time. Fish consumption advisories continue to be restrictive for many locations, species and size classes of fish. Ontario targets continued action toward long-term reductions in contaminants and fish consumption advisories.

Protecting Ontario’s rivers and streams from salt contamination

Road salt is used to clear ice and snow from roads, parking lots and sidewalks. However adding road salt to the environment risks contaminating drinking water sources. It can also harm the health of plants, animals and aquatic ecosystems. Several public- and private-sector programs encourage the responsible use of road salt. For example the Smart About Salt Council (affiliated with Landscape Ontario) has education and certification programs for landowners and private contractors. Ontario monitors salt levels in the environment and supports research to identify salt-vulnerable areas where added protections may be needed.

Road salt and snow storage best management practices have been developed by government and industry, primarily through the Transportation Association of Canada’s Syntheses of Best Practices: Road Salt Management framework, and Environment and Climate Change Canada’s Code of Practice for the Environmental Management of Road Salts. The best management practices typically included in a Road Salt Management Plan are proven and science-based.

Ontario continually reviews standards, new technology, equipment and materials to optimize winter maintenance practices. Maintenance operations have evolved significantly over time. New technology such as the Road and Weather Information Stations are used to predict winter storms and to assist with planning and deploying maintenance equipment and materials. New products such as pre-wetted salt and equipment innovations like automatic spreader controllers enhance the effectiveness of operations and decrease environmental impacts

Spotlight on science: road salt and our environment

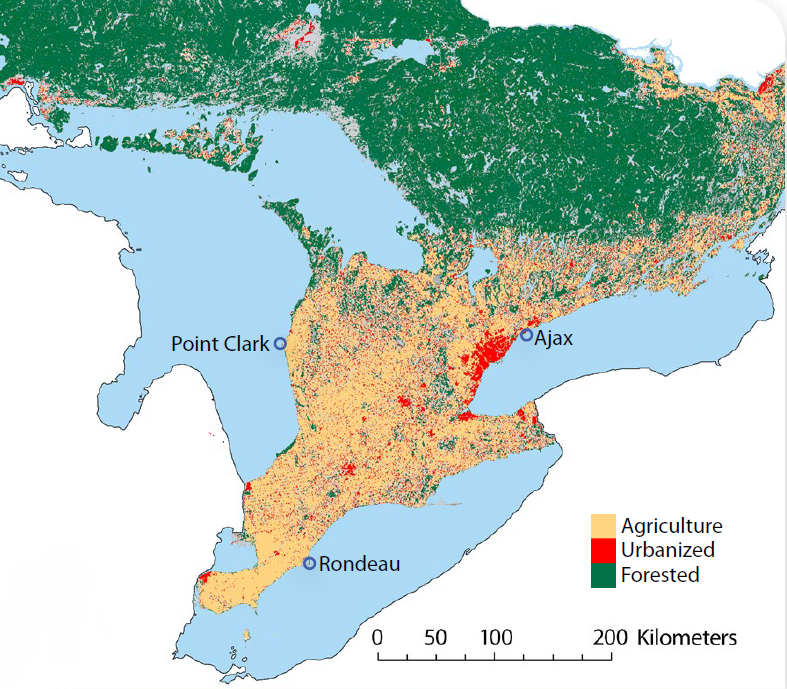

Freshwater mussels are particularly sensitive to chloride (a component of road salt) exposure compared to other aquatic life, especially during their early life stages. As part of the Provincial Water Quality Monitoring Network, Ontario has been monitoring concentrations of chloride in streams for decades. Chloride concentrations in many of our rivers and streams have been increasing.

Our studies have found that the application of road salt resulted in significant increases in chloride in mussel habitats. The rates of increase in chloride concentrations were highest at urbanized sites and lowest at forested sites. While scientists weren’t expecting it, they found that chloride concentrations at some sites peaked in the summer several months after the last application of road salt. This suggests that a portion of applied road salt stays in the environment and moves slowly. This has implications for freshwater mussels and other aquatic species in the Great Lakes. High levels of chloride concentrations in the summer can overlap with sensitive early life stages. It also suggests that there may be a time lag before reductions in the use of road salt are reflected in the environment.

You can learn more about the effects of salt contamination in the Water Quality in Ontario, 2014 Report.

Reducing stormwater and wastewater impacts

Better stormwater management helps communities adapt to climate change impacts, reduces sewage overflows and bypasses, and enhances protection of Ontario’s streams, lakes and aquatic life.

With input from a number of stakeholders and experts, Ontario is developing guidance on low impact development to add to its Stormwater Management Planning and Design Guidelines. This document is expected to outline how low impact development can be integrated into the stormwater management framework. It will provide guidance on targets for runoff volume control, climate change adaptation considerations and avoidance of negative effects on groundwater. It will also address the operation, inspection and maintenance of low impact development stormwater management systems. This guidance is targeted for release by the end of 2016.

In 2014, the updated Provincial Policy Statement (PPS) came into effect following review involving extensive public consultation. The PPS directs municipalities to consider the impacts of climate change in infrastructure planning and take proactive measures to promote stormwater management best practices in their infrastructure plans, including green infrastructure, low impact development and stormwater attenuation and re-use.

Showcasing solutions to enhance stormwater and wastewater management

Ontario’s Showcasing Water Innovation (SWI) program supported leading edge, innovative and cost-effective solutions for managing drinking water, stormwater and wastewater systems in Ontario communities. With 263 partnerships formed, the SWI program leveraged $35 million in partnership investments from a $17 million provincial investment. SWI has fostered innovation, created opportunities for economic development and protected water resources.

SWI funded 32 projects, of which 19 were linked to improving the Great Lakes and 16 directly involving the development and/or implementation of novel technologies and approaches for stormwater management. Six projects involved innovative wastewater treatment technologies. Examples include:

- the Upper Thames River Conservation Authority conducted pilot projects to determine the effectiveness of several best management practices for reducing phosphorus loading and erosion associated with rural drainage, ultimately reducing the potential impact of rural drainage on Lake St. Clair water quality. As a result of their work, better data and information is available on the performance of best management practices, so that better decisions can be made about best value solutions for reducing phosphorous loading and erosion in agricultural settings.

- the City of Guelph installed a novel process at its wastewater treatment facility to convert ammonia to nitrogen gas using significantly less energy than standard processes. Outcomes include a reduction of approximately 25% of the ammonia load to the facility; saving 650 kilowatt hours [kWh] of electricity per day ($17,000 per year); an improvement of effluent water quality discharged from the wastewater plant into the Grand River watershed which flows into Lake Erie; and lower greenhouse gas emissions.

- Credit Valley Conservation Authority advanced low impact development practices in Ontario by demonstrating their effectiveness and creating a series of guides to facilitate their implementation on public and private land. These practices resulted in cost-effective stormwater control even during large storms, reducing stress on aging municipal infrastructure and reducing pollutant loading to Lake Ontario. Guidance documents were created to help practitioners implement low impact development in their communities.

Reducing excessive nutrients

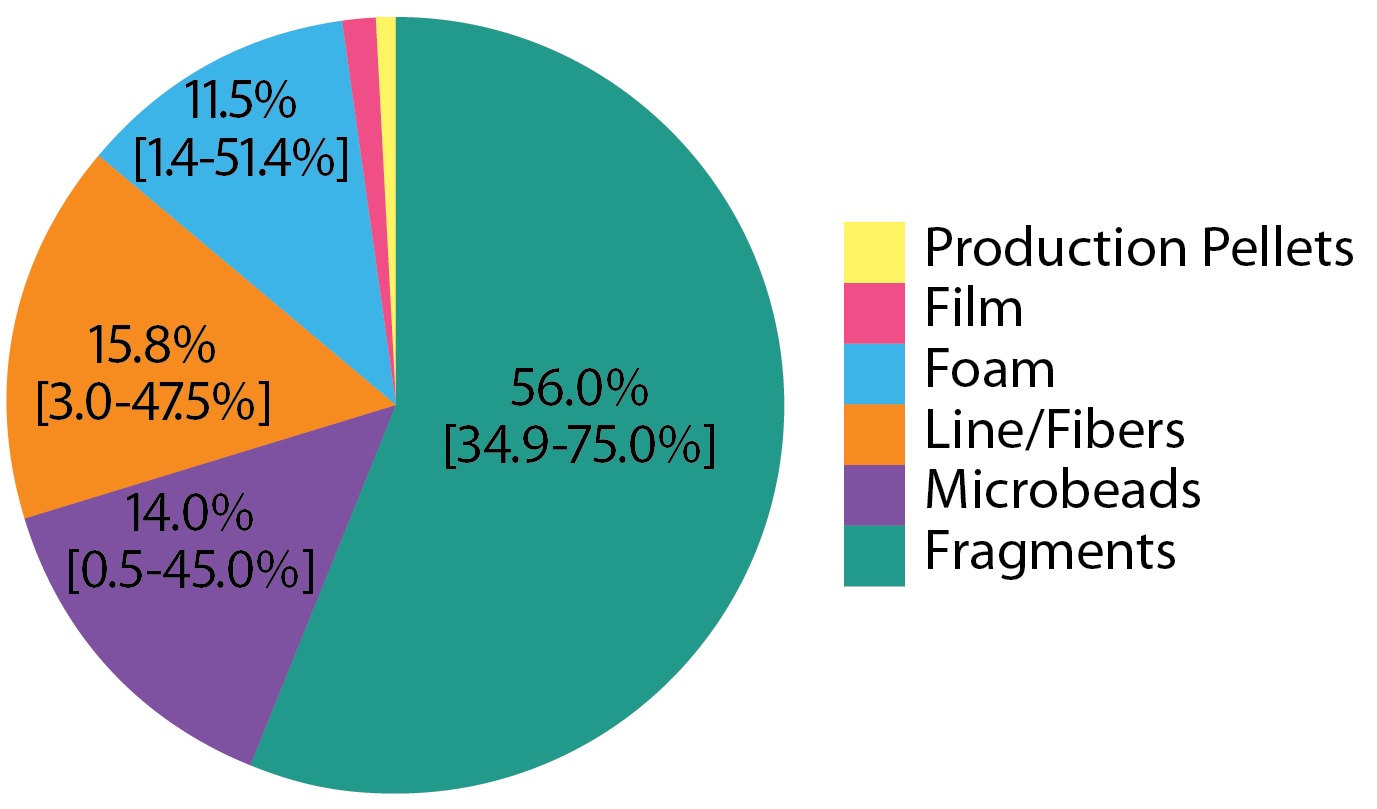

Phosphorus is the primary nutrient responsible for Great Lakes algal blooms. Following extensive phosphorus reduction efforts in the 1970s, algal blooms that had been threatening Lake Erie were largely absent. However, harmful blue-green and nuisance algal blooms began to reappear in the mid-1990s. The 2015 harmful algal bloom in western Lake Erie was the largest on record. Other locations within the Great Lakes such as the Bay of Quinte, Hamilton Harbour, the mouth of the Thames River, and the nearshore area in Leamington are also experiencing this type of algal bloom. These blooms can affect drinking water quality and be toxic to fish, wildlife and people. The die-off of these blooms is causing oxygen depletion in the central basin of Lake Erie and contributing to massive fish kills.

In addition, scientists have observed increases in the extent of nuisance algae (such as Cladophora) growing on the lakebed, particularly in eastern Lake Erie and western Lake Ontario. When these algae detach and accumulate along the coast they decompose and foul beaches and shorelines. Cladophora has also been linked to the occurrence of botulism (bacterial food poisoning) in wildlife.

Scientists are continuing to examine the causes of recent algae problems in Lake Erie. The amounts of phosphorus entering the lake had been decreasing into the 1990s but have since levelled off. A contributing factor has been colonization of the lakes by zebra and quagga mussels since the late 1980s. These invasive species have changed the bio-availability and increased light penetration in the lakes. Scientists are concerned that as the climate changes, earlier winter thaws, increased spring stream flows, and more intense rainfall events may wash more nutrients into the Great Lakes. These, combined with longer warm water periods, have the potential to increase the amount of unwanted algae.

The International Joint Commission (IJC) issued “A Balanced Diet for Lake Erie: Reducing Phosphorus Loadings and Harmful Algal Blooms” in 2014. This document made 16 recommendations relating to setting phosphorus reduction targets, reducing phosphorus loadings from agriculture, urban sources and septic systems, and strengthening monitoring and research. The IJC also released “Economic Benefits of Reducing Harmful Algal Blooms in Lake Erie” in 2015, which estimates nearly $71 million (U.S.) in lost economic benefits from the 2011 harmful algal bloom in the western basin of Lake Erie, and an additional $65 million from the 2014 bloom (Canadian and U.S. sides).

Phosphorus targets and actions

Phosphorus sources to Lake Erie include point sources (e.g., municipal sewage and industrial wastewater discharges) and non-point sources (e.g., runoff from agricultural lands, drainage from rural land, and urban stormwater). Given the number of sources, multi-jurisdictional and multi-stakeholder collaboration is essential for reducing nutrient loads to Lake Erie.

To help drive action in the near term, Ontario signed the Western Basin of Lake Erie Collaborative Agreement with Ohio and Michigan in June 2015, collectively committing, through an adaptive management process, to a 40% reduction in phosphorus entering Lake Erie’s western basin by the year 2025 with an aspirational interim goal of a 20% reduction by 2020 (from a 2008 base year). Ontario has also worked with the U.S. Lake Erie states of Ohio, Michigan, New York, and Pennsylvania through the Great Lakes Commission to develop a Joint Action Plan for reducing nutrient loadings to Lake Erie, which was released on September 29, 2015. Commitments arising from these initiatives will be incorporated into and implemented under the Domestic Action Plan for Lake Erie being developed by Ontario and Canada. Ontario actively worked with Canada and the U.S. to establish binational nutrient targets for Lake Erie, which were formally adopted in February 2016. Ontario is currently working with Canada to develop a Domestic Action Plan for Lake Erie, and plans to engage the Great Lakes community in 2016 to identify actions to address excessive nutrients and algal blooms.

Binational targets have been established to address harmful algal blooms in the western basin of Lake Erie (by addressing the Maumee River in Ohio), localized harmful algal blooms observed in the vicinity of several river mouths (the Maumee River in Ohio, five other watersheds in the U.S. and the Thames River and Leamington tributaries in Ontario), and oxygen depletion in the central basin of Lake Erie. In general, the targets call for a 40% reduction in phosphorus loads using 2008 as a base year. While scientists agree that the majority of the loadings to Lake Erie’s central basin are from U.S. sources, Ontario must do its fair share of reducing phosphorus loads by 40%, which translates to approximately 212 tonnes.

Ontario is taking action at home to complement these efforts. The Great Lakes Protection Act, 2015, requires the Minister of the Environment and Climate Change to set at least one target to support the reduction of algal blooms within two years, and Ontario will be consulting on a target.

Ontario’s 12-Point Plan on blue-green algal blooms outlines how we are working with our many partners to prevent and respond to algal blooms in the Great Lakes and other lakes and rivers, and protect drinking water supplies.

While current efforts are focussed on Lake Erie, future efforts will next be directed to establishing targets for Lake Ontario.

Measuring progress on Lake Erie nutrients

Ontario and its partners will work to achieve our binational phosphorous load reduction targets, and improved ecosystem outcomes for Lake Erie. We will continue to evaluate our progress on Lake Erie nutrients by ensuring that phosphorus loads into western and central Lake Erie from Ontario sources are measured. Ontario and its partners are working to determine how to best measure phosphorus at the mouths of key tributaries to track progress. We will also track the frequency and magnitude of Lake Erie western basin algal blooms and central basin hypoxia (oxygen depletion). Western basin algal blooms are increasing in frequency and severity. Phosphorus concentrations measured at drinking water intakes in the western basin have significantly decreased in comparison to the 1960s, but have been on the rise since the 1990s.

Spotlight on science: algal blooms

Ontario researchers are adding to our understanding of harmful algal blooms and nuisance algae. We are monitoring nearshore water quality at 17 drinking water intake sites in the Great Lakes, including five locations in Lake Erie. We also monitor 70 sites in the nearshore of the lakes to track long-term trends in Great Lakes water quality. These long-term data sets, together with special studies in the lakes and their tributaries, are helping us measure and understand nearshore responses to climate change and other stressors, including changes in nutrient loading. This is part of Ontario’s science contribution to the work on phosphorus reduction targets and actions.

Several recommendations for action have been made as a result of Ontario’s scientific studies. For example, science undertaken on Lake Erie’s central basin indicated that oxygen depletion (anoxia) caused the significant fish kills observed in 2012. This research helped to clarify the need for phosphorus reductions to protect Lake Erie’s central basin from oxygen depletion events.

Findings from stream monitoring and nearshore water quality research in the Leamington area indicated that high nutrient levels in coastal waters were primarily due to high phosphorus in the local water courses and water runoff along the shoreline, rather than being caused by the Leamington Water Pollution Control Plant. The study showed that while the phosphorus loads to this shoreline are minor compared to the total loads to the western Lake Erie basin, the chronic high levels of phosphorus in this area are stimulating unwanted algae growth. This area has now been identified as a binational priority for phosphorus reduction.

Scientific studies have also been assessing the distribution and persistence of excessive Cladophora and other attached algae in the Great Lakes, to help tackle algal fouling along beaches and waterfronts.

A satellite image of a Lake Erie algal bloom, taken on September 6, 2015 (NASA Worldview)

Agricultural best management practices

To develop and validate best management practices, Ontario’s technical specialists work with university scientists, the farming and agri-business community, federal counterparts and conservation authorities. Projects focus on nutrient management and water quality, as well as other Ontario agri-environmental needs such as natural heritage stewardship, soil health, energy efficiency and climate change.

The Best Management Practice Verification and Demonstration Program is designed to ensure best management practices are continually adapting to remain relevant with respect to modern agricultural production methods, evolving environmental issues and best available science. Program priorities are updated on a yearly basis to ensure research efforts are focused in the areas of primary concern. The program presently funds applied research to develop, validate and improve practices for water quality, soil health, climate change and nutrient management. Ontario provided six sites across Southern Ontario with farmland runoff monitoring equipment, automated water samplers and meteorological stations. This equipment supports year-round, high-frequency data collection for developing and verifying innovative best management practices that are good for the Great Lakes and effective for farmers. Positive actions are supported through applied on-farm research projects which develop and test the economic and environmental benefits of agriculture and food technology across the province.

For example, the best management practice for streamside grazing helps farmers properly plan and manage streamside grazing through improved buffers, alternative water access, stream crossings and pasture layout to benefit the environment. Other research examined the use of cover crops in field production systems and confirmed that keeping the soil surface covered during the late fall and early spring can reduce phosphorus and nitrogen loss into waterways.

Great Lakes agricultural stewardship

Agricultural land and nutrient management practices affect the health of soils. Good soil health prevents soil erosion, thereby reducing nutrient loss.

In February 2015, Ontario announced the Great Lakes Agricultural Stewardship Initiative. The program commits $16 million over four years to improve soil health and reduce nutrient loss from agricultural sources. Funding is provided through Growing Forward 2, a Canada-Ontario initiative, and targets the Lake Erie basin and the southeast shores of Lake Huron. This initiative supports private- and public-sector partnerships with cost-share funding to:

- identify ways producers can improve soil health, reduce runoff and improve pollinator habitat

- modify equipment to address risks related to manure application and pollinator health

- adopt best management practices, including soil erosion control structures, cover crops, residue management, buffer strips and field windbreaks/windstrips

The Great Lakes Agricultural Stewardship Initiative also offers technical training for service providers and education and outreach activities including local workshops

In 2015, with the support of Ontario, Fertilizer Canada and the Ontario Agri-Business Association launched a 4Rs Nutrient Stewardship program: “right fertilizer, right rate, right time, right place.” The adoption of this program was one of the recommendations of the Great Lakes Commission’s Joint Action Plan for reducing nutrient loads to Lake Erie. Under the 4Rs program, crop advisors use best management practices to make the most efficient use of fertilizers and can receive formal certification. The goal is matching nutrient supply with crop requirements and minimizing nutrient losses from fields.

Ontario is working collaboratively with federal departments, agricultural organizations and conservation authorities in the Lake Erie basin. This work focuses on finding better ways to understand and identify the Ontario agricultural areas that are most at risk of soil and nutrient loss. This work will help us meet phosphorus reduction targets to reduce harmful algal blooms and restore conditions in Lake Erie.

Early findings suggest that geographical features such as soil type and slope are important factors in how much nutrients are lost to streams from agricultural landscapes. Also, it appears that the largest amount of nutrient loss from agricultural landscapes occurs in winter and early spring. These early findings are helping us rethink our approaches to reducing algal fouling in the Great Lakes and set priorities.

Studying nutrients in Great Lakes agricultural watersheds

In 2013, Ontario launched the Multi-Watershed Nutrient Study. The seven-year study will examine the management of agricultural land and the extent of nutrient runoff in 11 agricultural watersheds in the basins of Lakes Erie, Ontario and Huron. This will be an ongoing study to determine the role agriculture can play in resolving a very complex issue.

This is the first broad-scale assessment of the extent of Ontario’s agricultural non-point source nutrient pollution to the Great Lakes in over 40 years. Comparative data from previous studies will be used to track changing climate conditions, to develop a “then-and-now” analysis and to model future scenarios.

Safeguarding water quantity

Ontario has worked with our Great Lakes neighbours to better protect and conserve the shared waters of the Great Lakes Basin, including improving our understanding of how water takings and climate change affect water availability. As part of this work, new rules were implemented in January 2015 for managing large water withdrawals and transfers within the Great Lakes Basin in ways that align with the Great Lakes- St. Lawrence River Basin Sustainable Water Resources Agreement signed by Ontario, Québec and the eight states that border the Great Lakes. The new rules enhanced Ontario’s existing Permit to Take Water program to ensure withdrawals in Ontario are managed to the standards of the agreement.

These new rules and Ontario’s ongoing work with our Great Lakes neighbours to support the agreement, aim to protect the waters of the Great Lakes and to allow us to better understand the impacts of water takings and climate change on the lakes.

The International Joint Commission (IJC) is a Canadian and U.S. organization established to manage shared waters such as the Great Lakes. The countries work together to investigate issues and recommend solutions.

Ontario undertakes work that contributes to activities of the IJC, helping us better understand the effects of regulated water levels in the Great Lakes. Regulating water levels can influence coastal wetlands through alterations to natural water levels and flow patterns in the Great Lakes. Ontario participates in IJC efforts in lake-level adaptive management planning to monitor the performance over the long-term of regulation plans in the Great Lakes system.

Focus for future action

Building on the accomplishments of Goal 2, future areas for action over the next few years to protect our Great Lakes waters will include:

- continuing to partner with First Nations communities to improve the quality and safety of drinking water

- taking action on harmful pollutants identified as priorities through the Canada-Ontario Chemicals of Concern process

- investigating the use of tools such as roadside ditch liners to reduce salt concentrations in surface and groundwater from highway runoff in localized salt sensitive areas

- issuing guidance on low impact development as part of Ontario’s stormwater management framework

- working with all affected partners on both sides of the border to reduce phosphorus loads to Lake Erie, to help reduce algal blooms and restore the health of the lake. Ontario will also continue to work on potential phosphorus reduction targets to help improve water quality in western Lake Ontario

- continuing to work with Québec and the eight Great Lakes States to protect and conserve Great Lakes Basin waters through the Great Lakes – St. Lawrence River Basin Sustainable Water Resources Agreement. Ontario will participate in reviewing significant water proposals, annually review Ontario’s water conservation programs and submit water use data to a regional database aimed at improving decisions and assessing water use impacts

Goal 3: Improving wetlands, beaches and coastal areas

Protecting Great Lakes coastal wetlands

Ontario’s Great Lakes coastal wetlands are among the region’s most ecologically valuable and productive habitats. Wetlands serve a variety of critical functions. They filter pollutants, store nutrients, regulate water flow to reduce flooding and erosion and are grounds for spawning, reproduction, food and shelter for many species.

Considerable work is underway to conserve and protect these threatened Great Lakes treasures. The Great Lakes Wetlands Conservation Action Plan, now in its fourth phase, is a cooperative effort by Canada, the Province, Conservation Ontario, Ducks Unlimited Canada, Ontario Nature, Nature Conservancy of Canada and other partners to more effectively protect and rehabilitate our remaining Great Lakes coastal wetlands. In 2014, the partners hosted the Great Lakes Wetlands Day with a focus on wetlands research and monitoring, policy and environmental conservation and management.

Building on over 30 years of wetland policy and partnership, Ontario is currently working across government to develop a Strategic Plan for Ontario’s Wetlands. The plan will provide a coordinating framework to guide wetland conservation. It will include a vision, goals and desired outcomes for wetlands and will set out a series of actions the Ontario government will undertake over the next 15 years to improve wetland conservation. This includes increasing our knowledge and understanding of wetland ecosystems and raising awareness about the importance of wetlands. It also includes ensuring our wetland polices are strong and effective, encouraging cooperation at all levels of government and supporting strategic partnerships for shared action on wetland conservation.

Measuring progress on conserving wetlands

Between 2006 and 2014, Ontario Eastern Habitat Joint Venture partners invested over $58.3 million to conserve wetlands and associated habitat across Ontario; this resulted in the securement of 37,379 hectares, the restoration of 12,217 hectares and the management of 46,023 hectares of wetland habitat.

Conserving migratory bird habitats in the Great Lakes

The Ontario Eastern Habitat Joint Venture (EHJV) is a collaborative partnership of government and non-government organizations in Ontario, working together to conserve wetlands and habitats that are important to waterfowl and other migratory birds. Since 1986, the Ontario EHJV and similar partnerships in other provinces have helped to implement habitat conservation programs that support continental waterfowl objectives identified under the North American Waterfowl Management Plan.

Ontario EHJV partners include: the Government of Canada, the Government of Ontario, Ducks Unlimited Canada, the Nature Conservancy of Canada, Bird Studies Canada, and Long Point Waterfowl. Partners work across Ontario, however, the focus is often in areas of southern Ontario where loss of wetland habitat has been highest.

Developing land-use planning policies that protect our wetlands

Ontario’s Provincial Policy Statement provides policy direction on land-use planning decisions across the province including the Great Lakes Basin, such as direction on the need to consider cumulative impacts of development in a watershed and improved protection for shoreline areas. Policies updated in 2014 prohibit development and site alteration in significant coastal wetlands and increase protection for all coastal wetlands in southern Ontario including the Lake Huron, Lake Erie and Lake Ontario watersheds. Currently Ontario is reviewing the Greenbelt Plan, Oak Ridges Moraine Conservation Plan, Niagara Escarpment Plan and Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe to ensure improved direction on watershed planning and protection of wetlands during land-use planning decisions.

Protecting Lake Erie’s wetlands

The Thames River flows southwest, passing through several communities, including Chatham and four First Nations reserves, before it empties into Lake St. Clair at Lighthouse Cove. This water then flows downstream to Lake Erie. In a project on the Lower Thames River watershed, multi-agency efforts are improving water quality and increasing biodiversity through restoration of critical coastal wetland habitat. Achievements from 2012 to 2015 include restoring 35 hectares of wetland and 25 hectares of provincially significant wetland, with another 291 hectares in four sites targeted for restoration, and many community events to raise awareness and encourage participation in restoring the coastline. These efforts work towards goals of the multi-agency Thames River Watershed Clearwater Revival Initiative.

On the north shore of Lake Erie, the Rondeau Bay Watershed is home to one of Lake Erie’s few remaining intact coastal wetland systems. It is an important refuge for many species at risk and is the site of a provincially significant wetland recognized as a Ramsar wetland of international importance. This watershed is also under a great deal of pressure from rural land uses, which ultimately affect the ecosystem health of Rondeau Bay. Following the recommendations of an ecological assessment led by Ontario, federal and community partners have been working collaboratively towards goals to enhance water quality and increase habitat quantity. Actions include creating wetlands, establishing shoreline vegetation buffers and incorporating green infrastructure into municipal drain design to reduce the inflow of nutrients from agricultural activities in the watershed.

The Long Point Coastal Wetland Complex, also on the north shore of Lake Erie, is another internationally-recognized Ramsar site. It is a critical stopover for migratory birds, located at the convergence of the Atlantic and Mississippi Flyways. The complex is an Important Bird Area and identified as a priority area for restoration under the EHJV and North American Waterfowl Management Plan. With over 5,000 hectares of provincially significant wetlands, most of the lands within the Long Point Wetland Complex are protected by government ownership or conservation easement, ensuring that wetland restoration activities undertaken will remain protected for generations to come. Ontario’s federal, municipal and community partners are working collaboratively to protect and restore aquatic habitat and improve water quality in the Long Point inner bay. Achievements include acquiring wetland habitat to ensure its protection, restoring degraded wetland habitat, decommissioning a sewage lagoon and restoring it to natural wetlands, monitoring the use of reconnected aquatic habitats by fish and wildlife, and controlling invasive Phragmites (common reed, a non-native plant).

Protecting Great Lakes beaches

The Healthy Lake Huron – Clean Water, Clean Beaches initiative

Ontario is chairing the Healthy Lake Huron- Clean Water Clean Beaches Initiative. Ministries are working collaboratively with a broad range of public- and private-sector partners to take a coordinated, community approach to improve overall water quality along Lake Huron’s southeast shores. The focus is addressing nuisance algae concerns and promoting safe and clean beaches and shorelines. Farmers are using a series of best management practices to improve soil health and keep valuable topsoil in their fields and away from Lake Huron. Working in collaboration with landowners, this initiative has completed over 200 on-the-ground actions aimed at improving water quality.

Monitoring the health of Great Lakes beaches

The quality of our Great Lakes beaches can be measured by the percentage of days that they meet bacterial standards and are therefore considered safe for swimming. In the Canada-U.S. reporting framework, a beach is given a Good rating if 80% or more of its beach days meet bacterial standards; a Fair rating at or above 70%; and a Poor rating if beach days meet bacterial standards less than 70% of the time. Between 2011-2014, Lake Superior and Lake Huron monitored beaches were assessed as Good (an unchanging trend from the previous reporting cycle, 2008-2010). Lake Ontario’s monitored beaches were assessed as Fair, relatively consistent with the previous reporting cycle. Lake Erie’s monitored beach status changed most significantly, from a Fair to Poor rating. The indicator information will be published as part of the next binational State of the Great Lakes report in 2017. To see previous State of the Great Lakes reports, visit binational.net/category/a10/sogl-edgl/.

To find out real time water quality information for swimming conditions at many beaches, visit the Lake Ontario Waterkeeper website to download the free Swim Guide smartphone app.

“Blue Flag” beach certification

The Blue Flag is a certification that a community’s beach or marina meets the stringent standards of the Foundation for Environmental Education. This Blue Flag designation can support the growth of the community’s tourism and economy.

There is strong support for using the Blue Flag beach program as the standard for healthy beaches. For example, Toronto has eight Blue Flag beaches. Surveys of aesthetics clearly indicate that Toronto’s beaches are clean, monitored and well-maintained.

Many of Ontario’s RTOs focus on beaches as a key attraction for their region. For example, the Southwest Ontario Tourism Corporation which borders Lakes Erie, Huron and St. Clair has been supporting the Blue Flag program and hosting workshops to introduce a variety of stakeholders to the program. The goal of the workshops is to increase awareness of the Blue Flag designation and encourage its adoption in southwest Ontario. There are currently three Blue Flag certified beaches in the region (Canatara Park, Grand Bend and Port Stanley), and two are currently applying for their certification (Erieau Beach and Port Glasgow Beach). In 2015, the Southwest Ontario Tourism Corporation also partnered with Blue Flag and Ryerson University to collect beach visitor data.

Cleaning and restoring Great Lakes beaches

Ontario has supported communities and groups that have taken action to restore and protect Great Lakes beaches. For example:

- The Bert Miller Nature Club planted beachgrass at five public beaches to repair and enhance the natural beach topography and sand dune ecosystems on the Niagara Peninsula of Lake Erie. The Club also built and installed three boardwalks to protect globally rare ecosystems by keeping foot traffic off sensitive dune habitats; educated visitors by installing interpretive signage; and created a pamphlet to raise awareness of this unique coastal environment.

- On the north shore of Lake Superior, the Sault North Waste Management Council and 40 volunteers held a cleanup of over five kilometres of shoreline. The program involved creating an educational presentation on the dangers of illegal dumping. The presentation was delivered at two local schools and an illegal dumping web page was added to the Sault North Waste Management Council’s website.

- The Garden River First Nation community has started the Ojibway Park shoreline restoration project, which includes a beach cleanup along Lake George in the Lake Huron watershed. Over the years the beach had become degraded due to lack of maintenance. Beach cleanup will improve the aesthetics and safety of the beach area and an environmental awareness campaign will help teach beach visitors about permitted and non-permitted beach activities. Various community groups are working together to develop a monitoring and ongoing maintenance plan to sustain the improved beach conditions.

Promoting beach stewardship

Ontario’s Great Lakes Strategy recognizes the ecological, social and economic importance of our Great Lakes beaches.

To promote good beach stewardship, Ontario released a new Recreational Water Protocol and a Beach Management Guidance Document in 2014. These documents provide updated guidance for public health units on assessing environmental conditions at public beaches, tracking water quality and communicating results to the public.

Ontario Parks, communities and partners along Lakes Erie and Huron and southern Georgian Bay are sponsoring a variety of activities to promote good beach stewardship, such as beach cleanups and vegetation planting. A beach stewardship video highlights the importance of sand beaches and coastal dunes for healthy, resilient coastal communities.

Achievements in restoring Areas of Concern

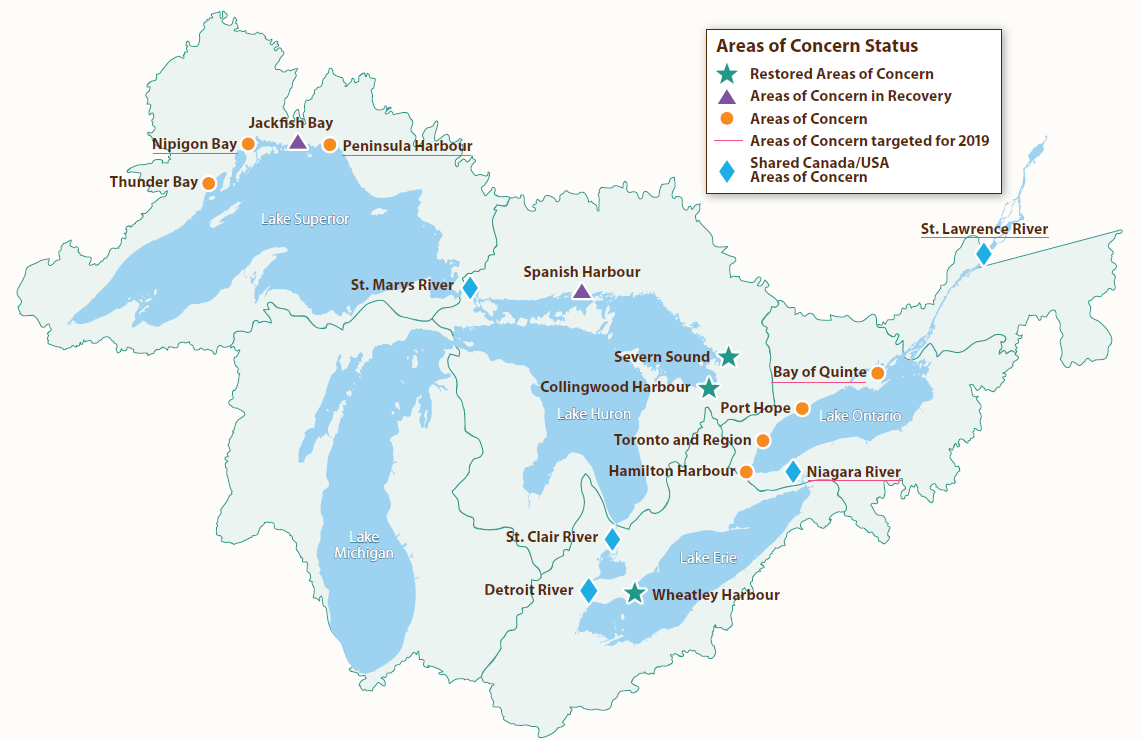

For more than 40 years, local residents, community groups, First Nations and Métis communities and industries have been working in partnership with Canada, Ontario and municipal governments to restore environmental quality in the Great Lakes. Since 1987, attention has been focused on cleaning up 17 sites known as Areas of Concern (AOCs), spots along the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River where water quality and ecosystem health had been severely degraded by human activity.

Considerable progress has been made to restore the 17 Canadian AOCs. Three AOCs in Ontario (Wheatley Harbour, Severn Sound and Collingwood Harbour) have completed all restoration actions and are no longer considered areas of concern. All restoration actions have been completed at two additional AOCs (Spanish Harbour and Jackfish Bay) and require time for the environment to recovery naturally. These two AOCs have been recognized as Areas of Concern in recovery.

Continued progress to restore environmental quality in the remaining AOCs has also been made, which is reflected in the number of beneficial uses that are no longer considered impaired (e.g. fish and wildlife deformities, loss of habitat and nuisance algal blooms). In the past three years Ontario has made substantive investments in the cleanup of contaminated sediments. Contaminated sediment management projects have been completed in the St. Lawrence River (Cornwall); Niagara River; Detroit River; Bay of Quinte; and the Peninsula Harbour AOCs. Initiatives are also underway to address environmental problems in Randle Reef in the Hamilton Harbour AOC.

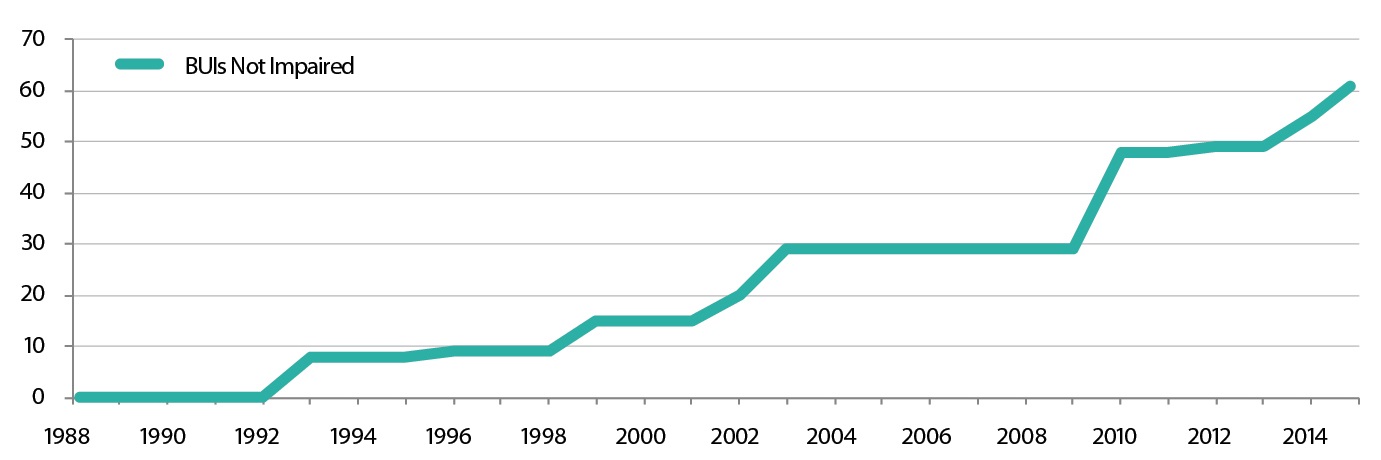

Number of beneficial uses no longer impaired in Canadian AOCs

Measuring progress on Great Lakes Areas of Concern

Progress on restoring Areas of Concern (AOCs) can be measured by the number of AOCs where all priority actions have been completed. So far, this milestone has been achieved at 5 of the 17 Areas of Concern that are located wholly or partially in Ontario. We have committed to completing priority restoration actions in five additional areas by 2019 – Nipigon Bay, Peninsula Harbour, Niagara River, Bay of Quinte and St. Lawrence River (Cornwall) – while continuing to advance restoration of the remaining AOCs.

Another important measure of progress is the number of “beneficial uses” no longer impaired (i.e., valued aspects of the environment that have been restored to health). To date, 61 beneficial uses across the 17 AOCs are no longer impaired, with more than half this progress occurring in the past five years.

Cleaning up contaminated sediment at Hamilton Harbour Area of Concern

All the Great Lakes drain through Lake Ontario. It has been most impacted by the accumulation of harmful pollutants. In addition the Lake Ontario basin is home to over 56% of Ontario’s population. This puts a great deal of pressure on its environment, infrastructure and transportation corridors. Despite these challenges Ontario and its partners have made significant progress in cleaning up the Areas of Concern along Lake Ontario’s shorelines. For example Randle Reef is an area of contaminated sediment located in the Hamilton Harbour AOC. A project is currently underway to safely address approximately 695,000 cubic metres of sediment contaminated with coal tar and heavy metals. The cost of the cleanup project is estimated at $138.9 million, with funding commitments from the Government of Canada, the Ontario government, the City of Hamilton, the City of Burlington, Halton Region, Hamilton Port Authority and U.S. Steel Canada. Ontario committed $46.3 million to this sediment cleanup.

Focus for future action

Building on the Goal 3 accomplishments, over the next few years we will help to protect and restore Great Lakes wetlands, watersheds, beaches, shorelines and coastal areas through a range of actions including:

- establishing and implementing a strategic plan for Ontario’s wetlands and supporting enhanced requirements for watershed planning and Great Lakes wetland protection through land use planning policies and guidance as well as stewardship programs

- completing all priority restoration actions in Nipigon Bay, Peninsula Harbour, Niagara River, Bay of Quinte and St. Lawrence River (Cornwall) by 2019 while also making progress on the restoration of other identified Areas of Concern

- working with local partners to advance the protection and restoration of other priority areas, using new tools in the Great Lakes Protection Act, 2015

Goal 4: Protecting habitats and species

Protecting Great Lakes habitat and species

Conserving biodiversity

The Ontario Biodiversity Council, which represents conservation and environmental groups, Aboriginal organizations, industry, academia and government, renewed Ontario’s Biodiversity Strategy (OBS) in 2011. OBS guides biodiversity conservation in the province and includes actions to engage all segments of Ontario society in valuing and conserving biodiversity.

In response to OBS, Ontario developed Biodiversity: It’s in Our Nature, Ontario Government Plan to Conserve Biodiversity, 2012-2020 (BIION). This document outlines key actions across 16 Ontario ministries to help achieve the vision and goals identified in OBS. These include activities to: increase biodiversity awareness and understanding; reduce threats to biodiversity including habitat loss, invasive species, pollution, population growth, unsustainable use and climate change; enhance the resilience of ecosystems including the Great Lakes; and support science, research and information management to inform biodiversity conservation. Ontario’s Great Lakes Strategy advances actions in BIION for both engaging people and enhancing resilience.

OBS includes a commitment to report on the state of Ontario’s biodiversity every five years. The State of Ontario’s Biodiversity 2015 report, released in May 2015, assesses the status of and trends for 45 indicators and evaluates progress against Ontario’s biodiversity targets. Several indicators are related to Great Lakes stressors, including the status of aquatic alien species in the Great Lakes (see “Combating invasive species,” below).

In May 2015, over 300 people attended the first ever Ontario Biodiversity Summit, which was hosted by the Ontario Biodiversity Council and Ontario. Summit participants learned and shared information about the state of biodiversity in the province, what Ontario is doing to protect it and where to focus future conservation efforts. The Summit included a Young Leaders for Biodiversity component where college and university students and young professionals had the opportunity to learn about emerging biodiversity issues and share ideas and experiences.

"We have been in the biodiversity business for a long time, long before the term biodiversity was even coined. Many of our long-term data sets are proving to be invaluable in how they support our resource management decisions, our understanding of trends over time, and their contribution to state of the resource reporting at all levels." Marty Blake, Director, Fish and Wildlife Services Branch, Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry

Protecting species at risk

The Great Lakes Basin is home to over 4,000 species of plants, fish and wildlife, some of which are not found anywhere else in the world. Sadly, many of our native plants and animals are at risk. The Endangered Species Act, 2007 identifies species at risk based on the best available scientific information and provides protection by requiring the development of recovery strategies or management plans for endangered and threatened species and their habitat.

Measuring progress on habitat restoration and recovering species at risk

The Province is implementing Ontario’s Land Stewardship and Habitat Restoration Program. Since its 2013 launch, the program’s $300,000 annual fund has helped improve, restore or create more than 4,662 acres of habitat including plantings of over 105,000 trees and shrubs, supporting the hiring of 182 people and leveraging over $2.3 million in project-partner funding.

To further promote recovery of species at risk in Ontario, the Province provides funding under the Species at Risk Stewardship Program. Ontario invests up to $5 million annually to encourage people to get involved in protecting and recovering species at risk through stewardship activities.

Funded projects under the Species at Risk Stewardship Program address key protection, recovery and research actions to support species at risk recovery strategies. Projects also support identified priority species (such as bats), ecosystems (such as wetlands) and issues (such as threats to pollinators). Entering its tenth year, this fund has supported over 820 projects. These projects have helped restore over 30,000 hectares of important habitat and protect many vulnerable Great Lakes Basin species, including the lake sturgeon, the American eel, the eastern hog-nosed snake and the piping plover. In 2015, the program funded over 100 new or ongoing multi-year projects.

Restoring native fish

Ontario has been collaborating with Canada and U.S. partners towards the rehabilitation of spawning habitats for several fish species, with a focus on Lake Sturgeon in the Detroit and St. Clair Rivers.

Ontario’s Understanding Constraints to Healthy Great Lakes Food Webs (“what eats what”) project focuses on Lake Ontario. This project is using advanced technologies to learn more about the habits of predatory and prey fish and invertebrates and the food-web linkages among them. Ecosystem research helps to inform restoration efforts underway on Lake Ontario for native fish species such as Atlantic salmon, bloater and lake trout.

Lake trout used to be Lake Huron’s dominant deep-water predator. The Province is continuing to work with the U.S. Geological Survey on the Lake Trout Rehabilitation Plan for Ontario Waters of Lake Huron. Parry Sound, Iroquois Bay and Fraser Bay in Northern Ontario are high-priority areas in the rehabilitation plan. Ontario is measuring progress in rehabilitating the lake trout, based on stocking success and the effectiveness of harvest restrictions.

Combating invasive species

As of 2014, over 180 non-native species have been reported to have reproducing populations in the Great Lakes Basin. No new invasive species have been discovered as established in the Great Lakes since 2006 and Ontario continues to work to prevent the establishment of new invasive species.

On November 3, 2015, Ontario was the first jurisdiction in Canada to pass an act to prevent, detect, respond to and, where feasible, eradicate invasive species. Our new Invasive Species Act, 2015 makes Ontario a national leader in invasive species prevention and management. The act gives the province new authority and tools to deal with invasive species in the Great Lakes.