Raven predation on sheep and beef farms in Ontario

Learn about raven predation on sheep and beef farms, including data and management tips.

ISSN 1198-712X, Published June 2023

Introduction

Predation by ravens on lambs, sheep and calves is something sheep and beef producers should be aware of and monitoring for. Ravens are extremely smart birds and can learn that lambs, sheep and calves are an easy food source. The majority of raven predation occurs during pasture lambing and calving. However, ravens will come into barnyards or barns and predate livestock in a confinement situation as well.

Injury or killing methods observed include:

- pecking eyeballs

- pecking skulls

- pecking tongues

- pecking rectums

- pecking noses

- pecking navels

- peck or pull at the hide

- puncture wounds throughout the body

- picking at abdomen

- tearing udders on ewes or cows

It should be noted that when bird predation occurs on live animals, blood will be present where the bird attacked the animal, for example, blood around the eyeballs, tongue, rectum, nose and navel (Figure 1). In the case of a stillborn animal, a scavenger such as a turkey vulture may come along and peck out the eyeballs, but no blood will be present since the animal was already dead. There may be exceptions to this based on weather conditions or carcass decomposition, which the producer should discuss with the Ontario Wildlife Damage Compensation Program (OWDCP) Investigator.

Data from the Ontario Wildlife Damage Compensation Program

Data from the OWDCP was compiled to observe trends in avian or bird predation for 2017–2022. Table 1 shows the number of approved OWDCP avian predation claims by county and by year for both lambs and sheep. Table 2 shows the number of approved OWDCP avian predation claims by county and by year for both calves and cows.

Both tables include injuries and kills. The data for all avian predators was combined, as often avian kills are hard to distinguish between species. The majority of reported kills or injuries were caused by ravens. There were a few claims reported as crows, eagles or vultures.

Table 1 shows that the highest avian predation claims on lambs and sheep occurred in 2022, followed by 2018. The year with the least number of bird claims was 2021. There are many different reasons why the numbers increase and decrease dramatically per year. For instance, some producers with raven predation problems had a livestock guardian dog that chased ravens away from the lambs and sheep or out of the pasture. In some cases, these dogs were older dogs that had to be replaced by younger dogs that did not chase birds. In other cases, the offending bird may have been lethally removed. Ravens are protected under Ontario’s Fish and Wildlife Conservation Act, 1997 (FWCA), however there are certain exemptions. Please consult the Act for current regulations.

In another example, one farm experienced a high number of losses from ravens killing lambs on pasture. The following year, the farm lambed ewes in barns, resulting in a lower rate of predation. This practice is not practical for most large pasture flocks and has other implications to consider. There are also some confinement sheep operations that have experienced problems with ravens coming into the barns and killing 41–50-kg (90–110-lb) lambs. Therefore, confinement is not a total solution, as the ravens continue to learn and adapt.

| County | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 6-year total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bruce County | 2 | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 3 |

| Dufferin County | N/A | 2 | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 3 |

| Durham Region | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 | 2 |

| Grey County | 3 | 6 | N/A | N/A | 3 | N/A | 12 |

| Huron County | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | 1 |

| Kawartha Lakes | N/A | 1 | N/A | N/A | 1 | N/A | 2 |

| Leeds and Grenville County | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | N/A | 1 | 9 |

| Lennox and Addington County | 1 | N/A | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 10 |

| Manitoulin District | N/A | 3 | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 4 |

| Nipissing District | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | N/A | 1 | 2 |

| Northumberland County | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | 8 | 9 |

| Ottawa Region | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | N/A | N/A | 1 |

| Parry Sound District | 13 | 4 | 15 | 17 | 3 | 52 | 104 |

| Peterborough County | N/A | 26 | 1 | 5 | N/A | N/A | 32 |

| Simcoe County | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 5 | 6 |

| Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry County | N/A | N/A | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 |

| Thunder Bay District | N/A | 5 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 5 |

| Timiskaming District | 4 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Wellington County | N/A | N/A | N/A | 6 | N/A | N/A | 6 |

| Total | 26 | 50 | 23 | 32 | 11 | 76 | 218 |

Table 2 shows that the number of bird predation claims on calves and cows remained fairly consistent year over year.

| County | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 6-year total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brant County | N/A | N/A | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 |

| Bruce County | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Cochrane District | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 | N/A | 3 |

| Durham Region | 1 | N/A | 1 | N/A | N/A | 2 | 4 |

| Frontenac County | N/A | N/A | 1 | N/A | 3 | N/A | 4 |

| Grey County | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | N/A | 1 | 10 |

| Haldimand County | N/A | N/A | 3 | N/A | N/A | 2 | 5 |

| Huron County | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | N/A | N/A | 1 |

| Kawartha Lakes | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | N/A | N/A | 8 |

| Lanark County | 1 | N/A | 2 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 3 |

| Leeds and Grenville County | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Manitoulin District | 1 | 4 | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 6 |

| Northumberland County | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 |

| Nipissing District | N/A | 4 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 14 |

| Ottawa Region | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | 2 |

| Parry Sound District | N/A | N/A | 1 | 1 | 1 | N/A | 3 |

| Peterborough County | N/A | N/A | N/A | 2 | 1 | N/A | 3 |

| Rainy River District | 3 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 18 |

| Renfrew County | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | N/A | 11 |

| Simcoe County | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | N/A | 8 |

| Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry County | N/A | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 |

| Sudbury Region | 1 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 17 |

| Thunder Bay District | N/A | 1 | 1 | N/A | 1 | N/A | 3 |

| Timiskaming District | 1 | N/A | N/A | 2 | N/A | 4 | 7 |

| York Region | N/A | N/A | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 |

| Total | 21 | 25 | 25 | 28 | 17 | 22 | 138 |

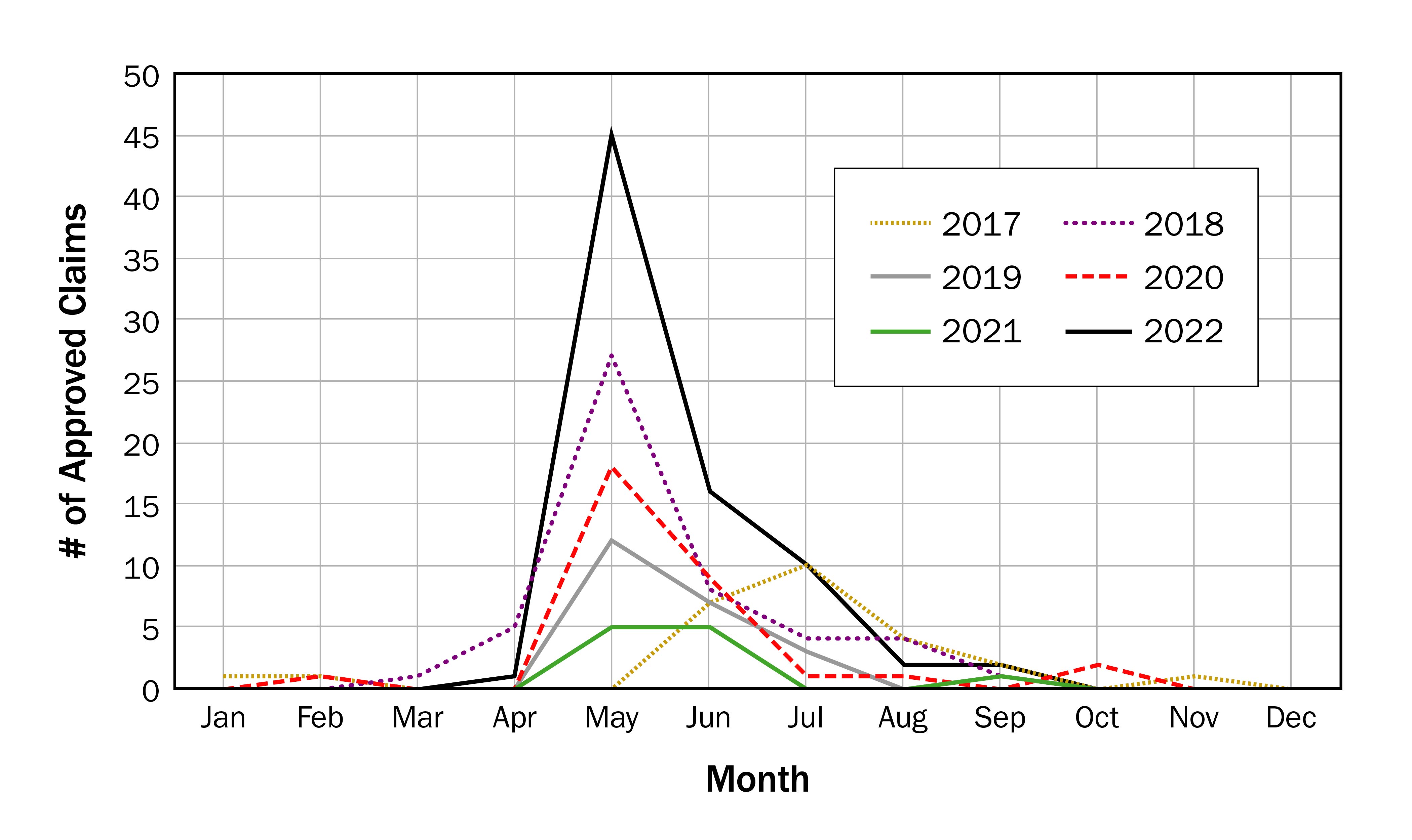

In Figure 2, the number of approved lamb and sheep OWDCP kills or injuries from birds can be seen by month over a 6-year period. The graph shows that most of the kills or injuries occurred in the month of May followed by June. This corresponds to pasture lambing.

In 2017, the spike in predation happened in July. This could have been simply because the ravens in the area had not yet developed kill behaviour on lambs or sheep and may have learned the killing behaviour later in the season.

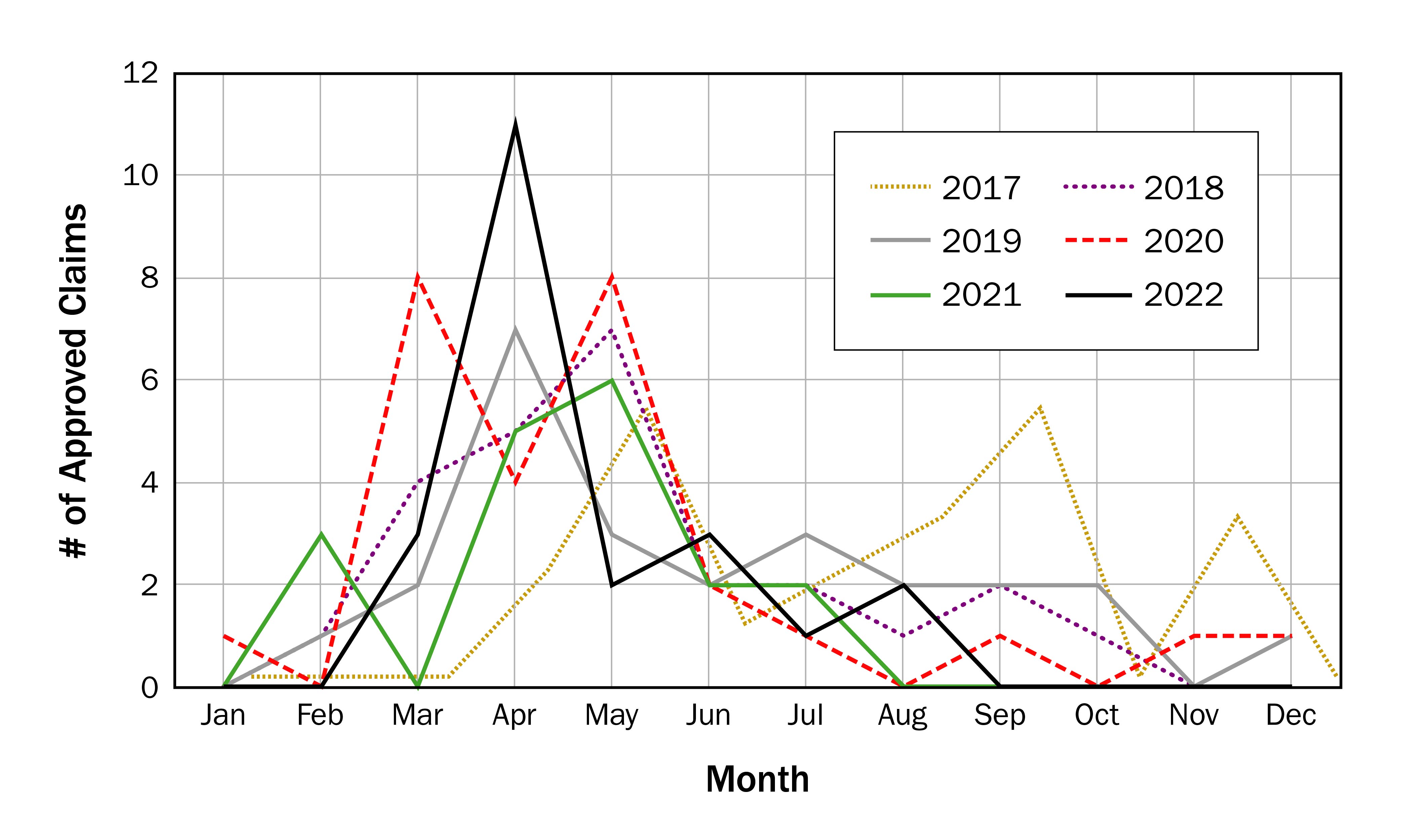

In Figure 3, the number of approved calf and cow OWDCP kills or injuries from birds can be seen by month over a 6-year period. The graph shows there are no evident trends in a certain month when predation occurs on beef. The spikes in bird predation are likely due to when farms were calving. From March to May, claims tend to be higher, which would correspond to spring calving. Other spikes in the fall could correspond to producers who had fall calving groups.

Summary

If a farm has not experienced raven predation and observes ravens frequently around the farm, trying to prevent the learned kill behaviour is ideal. Best management practices include cutting down dead trees in or around the pasture or removing unused silo platforms to eliminate easy roosting spots, picking up afterbirths and disposing of deadstock in a timely manner.

If the farm has experienced raven predation, there are limited reasonable care measures that can be used. Some options include livestock guardian dogs (although many will not chase ravens), non‑lethal deterrents, lethal removal of the offending bird or applying for a nest removal permit from the Ministry of Natural Resources (MNR). Additional information can be obtained from the local MNR district office. Search for MNR regional and district offices or by consulting Ontario’s FWCA.

If non-lethal deterrents are used on-farm, they should be set up only when the farm is experiencing active raven predation for short time periods. Ravens are very intelligent birds and will quickly become accustomed to the limited deterrents available (for example, scare-eye balloons, raven decoys, bird kites).

If a farm is experiencing active raven predation during pasture lambing or calving, set up deterrents directly prior to lambing or calving and remove them after the season is complete.

This fact sheet was written by Jillian Craig, small ruminant specialist, Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs.