Sampling soil and roots for plant parasitic nematodes

Learn about nematodes, their life cycle, symptoms, and how to sample for nematodes.

Overview

Nematodes are microscopic eel-like organisms that live in soil and water. They are the most abundant multicellular organisms on earth.

Most soil dwelling nematodes are beneficial organisms that play a role in the break down and release of nutrients from organic matter. Some beneficial nematodes prey on other nematodes as well as soil-borne insect, fungal and bacteria pests.

Unfortunately, there are several species of nematodes that feed on or in roots, stems or bulbs resulting in significant yield reduction in both field and horticulture crops grown in Ontario (Figure 1). They may cause direct damage to plant health or indirectly by opening the path to plant body for other plant pathogens.

Plant parasitic nematodes possess a hollow stylet - a mouth part resembling a hypodermic syringe (Figure 2). The stylet is forced into plant cells and enzymes are injected to decompose the cell content. The nematode withdraws the partially digested cell contents through the stylet.

Endoparasitic nematodes, such as root knot and cyst nematodes, feed inside the root tissue and spend a part of their life cycle attached to the root. While ectoparasites, such as root lesion or ring nematodes, burrow into the root, feeding and causing damage from outside of the root.

Source: Singh and Phulera (2015).

Plant parasitic nematodes in Ontario

Several different types of plant parasitic nematodes inhabit different regions of Ontario.

These include the:

- soybean cyst nematode (Heterodera glycines), which is spreading throughout parts of Southwestern Ontario

- oat cyst nematode (H. avenae)

- sugar beet cyst nematode (H. schachtii)

- northern rootknot nematode (Meloidogyne hapla)

- bulb and stem nematode (Ditylenchus dipsaci)

- dagger nematode (Xyphinema sp.)

- root lesion nematode (Pratylenchus penetrans)

- ring nematode (Mesocriconema xenoplax)

Most cyst nematodes tend to have limited host range, except for the sugar beet cyst nematode that can infect over 220 hosts including most cole crops.

The bulb and stem nematode has a wide host range and several races. In Ontario, it tends to only cause significant damage to onions and garlic.

The Northern root knot nematode also has a wide host range and is particularly damaging to carrots.

The root lesion nematode is considered the most economically important plant parasitic nematode in Ontario fruit and vegetable production. Root lesion nematodes have a wide host range including many native weeds.

Both dagger and ring are found to be present in most of the southern Ontario tree fruit orchards, including small berry orchards such as blueberry and strawberry.

Nematode life cycle

Most plant parasitic nematodes lay eggs in the soil or roots of host plants or are retained within the female body or cyst. After the eggs hatch, the juvenile nematodes swim to other nearby plant roots and feed on them.

Damage caused by nematodes in many crops can also provide an infection site for other disease-causing organisms, which further reduces yields.

Nematodes complete their life cycle within 3 to 6 weeks during the growing season depending upon available moisture and temperature. Extreme moisture and temperatures will kill some species of nematodes.

Symptoms of nematode damage

Symptoms caused by nematode infestation differ depending on the crop and the type of nematode pest.

Nematode damaged plants usually occur in patches or along a row. Infested plants may appear stunted, wilted and unthrifty. Nematode feeding also causes symptoms such as:

- yellowing

- stem twisting

- crown and bulb bloating

- root galls

- root forking and distortion

High soil population levels of plant parasitic nematodes can cause death of young plants. Frequently, the damage caused by nematodes goes undetected because of the difficulty of diagnosing nematode damage and infestation, resulting in the loss of millions of dollars in crop production annually.

Taking soil and/or root samples at the proper time of year for analysis of nematode populations can help growers avoid or reduce the potential of nematode problems in their crops. This should be done by a qualified laboratory accredited to identify and enumerate nematodes.

Root lesion nematodes cause small scratch-like lesions on feeder roots providing an avenue for other root rotting organism to infect (Figure 3). In fact, root lesion nematodes have frequently been associated with disease complexes involving other soil-borne pathogens resulting in significantly greater disease and reduced yields compared to either the fungal pathogen or nematode infection alone. Some parasitic nematodes such as the dagger nematode are vectors for plant viruses.

Roots that have small pearl-like structures along feeder roots may be an indication of cyst nematode. The small cysts may be white, yellow or brown in appearance depending on the species of the cyst nematode. Northern root knot nematodes cause roots to appear stubby or swollen and often result in excessive secondary root branching giving the root a hairy appearance (Figure 4).

Growers who notice patches of plants with unusual root symptoms, severe root rot or a patch that appears to decline quicker than the rest of the field may suspect a nematode problem and should consider sampling roots and soil for nematode analysis.

When to take root samples

Root and soil samples containing roots can be taken at any time as long as the soil is not frozen. However, samples collected in fall will be ideal for nematode identification. During the active growing season nematodes live and feed inside or along roots particularly during hot dry seasons.

If nematodes are suspected of contributing to the decline of a particular area of a young crop during the growing season, collect entire root systems with surrounding soil separately from plants with symptoms and plants without symptoms. If the decline is noticed in a fruit tree orchard, vineyard or other perennial crop, carefully dig and sample from the feeder root zone approximately 10-20 g fresh weight of roots from the infected plants and submit for analysis.

Do not sample the roots from dead plants because the nematodes will have already died or moved away from dead roots into the soil. Place samples in a plastic bag out of direct sunlight and in a cool place during transportation to the diagnostic lab.

When to take soil samples

The best time to sample soil for nematode population assessment is in the spring after the soil has warmed up or during the fall, soon after harvest. Do not take nematode samples when fields are very wet. The best day for nematode soil collection should be within temperatures of 25 to 28°C (not too dry and not right after a heavy rain).

Fields with a history of nematode problems may be sampled routinely to determine if the nematode population is approaching or has exceeded an economic threshold.

Soil populations of most plant parasitic nematodes tend to be highest in September and October after crops have senesced and died. This is the best time of year to sample for nematodes.

Sampling in the early fall allows growers time to make decisions on whether to fumigate during the fall or spring or what crop should be planted the following spring. It also allows time to implement an integrated management strategy prior to growing a susceptible crop in that field. Sampling in the spring prior to planting a crop may also be reliable.

Where to sample soil

The best place to sample soil for nematode assessment depends on:

- the purpose of taking the soil sample

- the type of crop in the field

- the type of nematodes being sampled

If the purpose of sampling soil for nematodes is to diagnose a problem during the growing season in a row crop, take 8 to 10 soil cores from areas where plants are unhealthy or near plants along the margin of a severely affected area. Sample another 8 to 10 soil cores separately from areas of healthy growing plants for comparison (Figure 5).

When sampling soil from row crops during the growing season, or from trees or perennial crops, it is very important to get the feeder roots of the crop in the soil sample, since this is where many nematodes live.

For individual fruit trees or ornamental shrubs suspected of being infested with nematodes, it is best to take soil samples from just below the drip line and in the area between the outer branch tips and the tree trunk (Figure 6).

If the purpose of sampling a field is to determine whether the nematode population has reached an economic threshold in a row crop, take soil cores within the row of actively growing plants to obtain samples that contain feeder roots (Figure 7).

When sampling from fallow fields, in the autumn after the crop has senesced or in the spring prior to planting, it is best to walk in a Z, W or M pattern across the field (Figure 8). The soil sample should represent no more than 2.5 ha.

How to sample soil

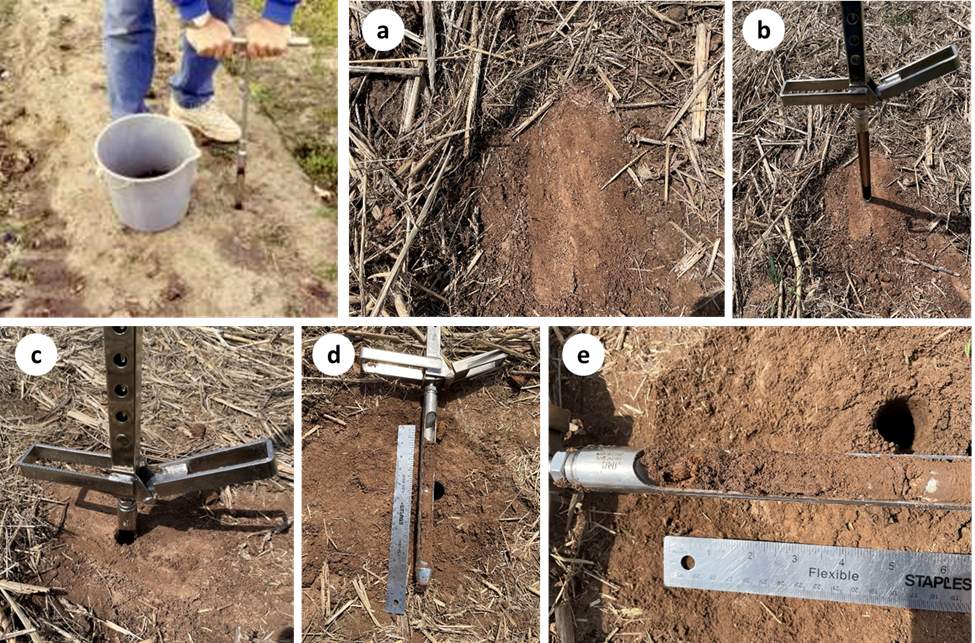

Nematodes are rarely distributed evenly throughout a field and nematode populations fluctuate throughout the growing season. Clean the sample area to increase the chance of sampling soil only by removing covers. Soil should be sampled approximately 25 to 30 cm deep using a 2.5-cm (1-in.)-diameter soil core probe (Figure 9).

- Clean the top area.

- Set a 2.5 cm probe for soil sampling.

- Deep the probe into soil for 30 cm.

- Take out the probe.

- Remove top 3 cm to 5 cm of soil and collect the rest into a sampling bag.

Alternatively, soil can be sampled with a narrow-bladed shovel or trowel. However, this method is less reliable than using a soil core probe. Extremely wet, dry, hot or cool seasons can influence the population levels particularly in the top 2.5 to 5 cm (1-2 in.) of soil. Discard the top 2.5 to 5 cm (1-2 in.) of soil where nematodes would not usually live due to extreme environmental conditions.

Collect soil cores in a clean bucket, mix the soil thoroughly but gently and place it in a labelled plastic bag or container. Never allow soil samples to heat up or dry out. Place soil samples in a cooler with ice until they can be stored in a fridge or analyzed for nematode populations.

Number of soil cores/area

The number of soil core samples required to estimate nematode soil population levels, depends on the size of the area under investigation (Table 1).

| Area | Number of soil cores/sample |

|---|---|

| < 500 m2 | 8 to 10 |

| 500 m2 to 0.5 ha | 25 to 35 |

| 0.5 ha - 2.5 ha | 50 to 60 |

The sample submitted to the laboratory should not represent more than 2.5 ha. Enough soil to give a good representation of the soil population is all that is necessary.

Table 1 is a guide of how many cores are necessary to make up a representative sample. If soil type changes within the field, take separate samples from each soil type. Send the soil samples to a pest diagnostic clinic or laboratory that is qualified to isolate, identify and enumerate nematodes.

Confirm that the diagnosis lab can identify all plant parasitic nematodes present in soil samples. Depending on nematode extraction protocol, the sample may not retain all sizes of nematodes, meaning important information will likely be missed. For example, bigger nematodes such as ring or dagger may be underrepresented in the sample if regular pan extraction method is used for nematode isolation.

Economic thresholds

Economic thresholds are based on initial soil population levels that will multiply over the growing season and cause economic damage to the crop. The economic threshold is expressed as the number of nematodes in a kilogram of soil and is often different for each crop and each nematode species (Table 2).

| Nematode | Economic threshold: soil (nematodes/kg soil) | Economic threshold: root (nematodes/50 g dry root) | Crops |

|---|---|---|---|

| Root lesion | 500 | N/A | Strawberry |

| Root lesion | 2,000 | N/A | Vigorous growing processing tomato varieties |

| Root lesion | 1,000 | 50 | Most other crops |

| Root knot | 0 | 0 | Carrot, parsnip, tomato |

| Root knot | 500 | N/A | Onions, potatoes |

| Root knot | 1,000 | N/A | Most other crops |

| Pin | 5,000 | N/A | Most crops |

| Dagger | 100 | N/A | Most crops |

| Bulb and stem | 100 | N/A | Most crops |

| Sugarbeet cyst | 2,000 larva or eggs (> 250 cysts) | N/A | Sugar beets, cruciferous crops |

| Soybean cyst | 2,000 larva or eggs (> 250 cysts) | N/A | Soybeans |

Threshold levels from as high as 1,000 root lesion nematodes/kg of soil for most vegetables to as few as 500/kg of soil in strawberry can significantly reduce yields. If the nematode soil analysis report indicates populations higher than the threshold, an integrated nematode management strategy should be implemented.