The Kindergarten Program 2016

The Kindergarten Program 20162019 Addendum

PDF, The 2019 Addendum to The Kindergarten Program – Revised Specific Expectations 6.4 and 24.1, 84 KB

Preface

This document supersedes The Full-Day Early Learning–Kindergarten Program (Draft Version, 2010‑11). Beginning in September 2016, all Kindergarten programs will be based on the expectations and pedagogical approaches outlined in this document.

Elementary schools for the twenty-first century

Ontario elementary schools strive to support high-quality learning while giving every child the opportunity to learn in the way that is best suited to the child's individual strengths and needs. The Kindergarten program is designed to help every child reach his or her full potential through a program of learning that is coherent, relevant, and age appropriate. It recognizes that, today and in the future, children need to be critically literate in order to synthesize information, make informed decisions, communicate effectively, and thrive in an ever-changing global community. It is important for children to be connected to the curriculum, and to see themselves in what is taught, how it is taught, and how it applies to the world at large. The curriculum recognizes that the needs of learners are diverse and helps all learners develop the knowledge, skills, and perspectives they need to become informed, productive, caring, responsible, and active citizens in their own communities and in the world.

The introduction of a full day of learning for four- and five-year-olds in Ontario called for transformational changes in the pedagogical approaches used in Kindergarten, moving from a traditional pedagogy to one centred on the child and informed by evidence from research and practice about how young children learn. The insights of educators in the field, along with knowledge gained from national and international research on early learning, have informed the development of the present document.

Background

The Ontario government introduced Kindergarten ‑ a two-year program for four- and five-year-olds ‑ as part of its initiative to create a cohesive, coordinated system for early years programs and services across the province. Milestones in the creation of that system include the following:

- In 2007, the government published Early Learning for Every Child Today: A Framework for Ontario Early Childhood Settings, commonly referred to as ELECT, which set out six principles to guide practice in early years settings:

- Positive experiences in early childhood set the foundation for lifelong learning, behaviour, health, and well-being.

- Partnerships with families and communities are essential.

- Respect for diversity, equity, and inclusion is vital.

- An intentional, planned program supports learning.

- Play and inquiry are learning approaches that capitalize on children's natural curiosity and exuberance.

- Knowledgeable, responsive, and reflective educators are essential.

ELECT is recognized as a foundational document in the early years sector. It provided a shared language and common understanding of children's learning and development for early years professionals as they work together in various early childhood settings. The principles of ELECT informed provincial child care policy as well as pan-Canadian early learning initiatives such as the Statement on Play of the Council of Ministers of Education, Canada. ELECT principles were embedded in the innovative Kindergarten program outlined in The Full-Day Early Learning–Kindergarten Program (Draft Version, 2010–11).

- The Ontario Early Years Policy Framework, released in 2013 and also based on ELECT, set the stage for the creation of the new early years system, providing a vision to ensure that children, from birth to age six, would have the best possible start in life. The policy framework guides Ontario's approach to the development and delivery of early years programs and services for children and families.

- How Does Learning Happen? Ontario's Pedagogy for the Early Years, released in 2014, built on this policy framework. It sets out a fundamental understanding of children, families, and educators that is shared by educators across child care and education settings, and a pedagogical framework that supports children's transition from child care to Kindergarten and the elementary grades.

- The present document – The Kindergarten Program (2016) – sets out principles, expectations for learning, and pedagogical approaches that are developmentally appropriate for four- and five-year-old children and that align with and extend the approaches outlined in How Does Learning Happen?

Supporting Children's Well-Being and Ability to Learn

Promoting the healthy development of all children and students, as well as enabling all children and students to reach their full potential, is a priority for educators across Ontario. Children's health and well-being contribute to their ability to learn, and that learning in turn contributes to their overall well-being.

Educators play an important role in promoting the well-being of children and youth by creating, fostering, and sustaining a learning environment that is healthy, caring, safe, inclusive, and accepting. A learning environment of this kind will support not only children's cognitive, emotional, social, and physical development but also their mental health, their resilience, and their overall state of well-being. All this will help them achieve their full potential in school and in life.

A focus on well-being in the early stages of a child's development is of critical importance. The Kindergarten Program integrates learning about well-being into the program expectations and pedagogy related to "Self-Regulation and Well-Being", one of the four "frames", or broad areas of learning, in Kindergarten. Educators take children's well-being into account in all aspects of the Kindergarten program. A full discussion of what educators need to know to promote children's well-being in all developmental domains, and to support children's learning about their own and others' well-being, is provided in Chapter 2.2, "Thinking about Self-Regulation and Well-Being".

Foundations for a Healthy School

Ontario schools provide all children in Kindergarten and all students in Grades 1 to 12 with a safe and healthy environment for learning. Children's learning in Kindergarten helps them make informed decisions about their health and well-being and encourages them to lead healthy, active lives. This learning is most authentic and effective when it occurs within the context of a "healthy" school – one in which children's learning about health and well-being is reinforced through policies, programs, and initiatives that promote health and well-being.

The Ministry of Education's Foundations for a Healthy School: Promoting Well-Being as Part of Ontario's Achieving Excellence Vision identifies how schools and school boards, in partnership with parents

- Curriculum, Teaching, and Learning

- School and Classroom Leadership

- Student Engagement

- Social and Physical Environments

- Home, School, and Community Partnerships

Collectively, the strategies, policies, and initiatives that schools undertake within these areas contribute to a positive school climate, in which all members of the school community feel safe, included, and accepted and which promotes positive, respectful interactions and healthy relationships.

The principles and pedagogical approaches that define the Kindergarten program promote healthy-school principles and practices in all five of the areas noted above. Children's learning in the frames "Belonging and Contributing" and "Self-Regulation and Well-Being" is focused on knowledge and skills related to health and well-being. More detailed information about the ways in which the Kindergarten program promotes children's health and well-being in all five areas may be found in the following sections and chapters:

- "Well-Being: What Are We Learning from Research?", in Chapter 2.2, "Thinking about Self-Regulation and Well-Being"

- Chapter 1.3, "The Learning Environment"

- "Play-Based Learning: The Connections to Self-Regulation", in Chapter 1.2, "Play-Based Learning in a Culture of Inquiry"

- Chapter 3.2, "Building Partnerships: Learning and Working Together"

- "Health and Safety in Kindergarten", in Chapter 3.1, "Considerations for Program Planning"

Is your child about to enter kindergarten? This document sets out what four- and five-year-olds across the province will learn in Ontario’s two-year kindergarten program and how educators will help your child learn through play and inquiry.

We're moving content over from an older government website. We'll align this page with the ontario.ca style guide in future updates.

Part 1: A program to support learning and teaching in Kindergarten

Part 1: A program to support learning and teaching in Kindergarten robertallisonPart 1 outlines the philosophy and key elements of the Kindergarten program, focusing on the following: learning through relationships; play-based learning in a culture of inquiry; the role of the learning environment; and assessment for, as, and of learning through the use of pedagogical documentation, which makes children's thinking and learning visible to the child, the other children, and the family.

1.1 Introduction

- Vision, Purpose, and Goals

- The Importance of Early Learning

- A Shared Understanding of Children, Families, and Educators

- Pedagogy and Programs Based on a View of Children as Competent and Capable

- Pedagogical Approaches

- Fundamental Principles of Play-Based Learning

- The Four Frames of the Kindergarten Program

- Supporting a Continuum of Learning

- The Organization and Features of This Document

1.2 Play-Based Learning in a Culture of Inquiry

- Play as the Optimal Context for Learning: Evidence from Research

- How Do Children Learn through Play?

- Play-Based Learning: The Connections to Self-Regulation

- The Inquiry Approach: Evidence from Research

- Play-Based Learning in an Inquiry Stance

- The Critical Role of the Educator Team: Co-constructing Inquiry and Learning

- How Does the Inquiry Approach Differ from Theme-Based or Unit Planning?

- Communicating with Parents and Families about Play-Based Learning

1.3 The Learning Environment

- Rethinking the Learning Environment

- Thinking about Time and Space

- Thinking about Materials and Resources

- Co-constructing the Learning Environment

- The Learning Environment and Beliefs about Children

- Learning in the Outdoors

1.4 Assessment and Learning in Kindergarten: Making Children’s Thinking and Learning Visible

- Pedagogical Documentation: What Are We Learning from Research?

- Using Pedagogical Documentation to Best Effect

- From Traditional Note Taking to Pedagogical Documentation

- The Importance of Educator Self-Awareness in Pedagogical Documentation

- Co-constructing Learning with the Children: Assessment for Learning and Assessment as Learning

- Assessment for Learning

- Sustained Shared Thinking

- Assessment as Learning

- Assessment for Learning

- Noticing and Naming the Learning: The Link to Learning Goals and Success Criteria

- Considerations in Assessment of Learning: Children’s Demonstration of Learning

- Collaborating with Parents to Make Thinking and Learning Visible

1.1 Introduction

1.1 Introduction robertallisonVision, purpose, and goals

The Kindergarten program is a child-centred, developmentally appropriate, integrated program of learning for four- and five-year-old children. The purpose of the program is to establish a strong foundation for learning in the early years, and to do so in a safe and caring, play-based environment that promotes the physical, social, emotional, and cognitive development of all children.

The primary goals of the Kindergarten program are:

- to establish a strong foundation for learning in the early years;

- to help children make a smooth transition from home, child care, or preschool settings to school settings;

- to allow children to reap the many proven benefits of learning through relationships, and through play and inquiry;

- to set children on a path of lifelong learning and nurture competencies that they will need to thrive in the world of today and tomorrow.

The Kindergarten program reflects the belief that four- and five-year-olds are capable and competent learners, full of potential and ready to take ownership of their learning. It approaches children as unique individuals who live and learn within families and communities. Based on these beliefs, and with knowledge gained from research and proven in practice, the Kindergarten program:

- supports the creation of a learning environment that allows all children to feel comfortable in applying their unique ways of thinking and learning;

- is built around expectations that are challenging but attainable;

- is flexible enough to respond to individual differences;

- provides every child with the kind of support he or she needs in order to develop:

- self-regulation;

- health, well-being, and a sense of security;

- emotional and social competence;

- curiosity, creativity, and confidence in learning;

- respect for diversity;

- supports engagement and ongoing dialogue with families about their children's learning and development.

The vision and goals of the Kindergarten program align with and support the goals for education set out in Achieving Excellence: A Renewed Vision for Education in Ontario (2014) – achieving excellence, ensuring equity, promoting well-being, and enhancing public confidence.

The importance of early learning

[Early childhood is] a period of momentous significance … By the time this period is over, children will have formed conceptions of themselves as social beings, as thinkers, and as language users, and they will have reached certain important decisions about their own abilities and their own worth. (Donaldson, Grieve, & Pratt, 1983, p. 1)

Evidence from diverse fields of study tells us that children grow in programs where adults are caring and responsive. Children succeed in programs that focus on active learning through exploration, play, and inquiry. Children thrive in programs where they and their families are valued as active participants and contributors.From How Does Learning Happen? (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2014c, p. 4)

Early childhood is a critical period in children's learning and development. Early experiences, particularly to the age of five, are known to "affect the quality of [brain] architecture by establishing either a sturdy or a fragile foundation for all of the learning, health and behavior that follow" (Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University, 2007).

Children arrive in Kindergarten as unique individuals shaped by their particular cultural and social background, socio-economic status, personal capabilities, and day-to-day experiences, and at different stages of development. All of these factors influence their ability to reach their full potential. Experiences during the early years strongly influence their future physical, mental, and emotional health, and their ability to learn.

For these reasons, children's early experiences at school are of paramount importance. Quality early-learning experiences have the potential to improve children's overall health and well-being for a lifetime. By creating, fostering, and sustaining learning environments that are caring, safe, inclusive, and accepting, educators can promote the resilience and overall well-being of children. The cognitive abilities, skills, and habits of mind that characterize lifelong learners have their foundation in the critical early years.

In addition, it is essential for programs to provide a variety of learning opportunities and experiences based on assessment information that reveals what the children know, what they think and wonder about, where they are in their learning, and where they need to go next. Assessment that informs a pedagogical approach suited to each child's particular strengths, interests, and needs will promote the child's learning and overall development.

The importance of early experiences for a child's growth and development is recognized in the design of The Kindergarten Program, which starts with the understanding that all children's learning and development occur in the context of relationships – with other children, parents and other family members, educators, and the broader environment.

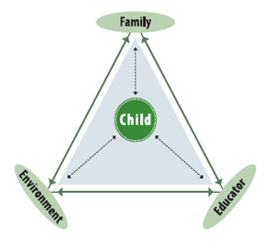

Figure 1. Learning and development happen within the context of relationships among children, families, educators, and their environments.

A shared understanding of children, families, and educators

The understanding that children, families, and educators share about themselves and each other, and about the roles they play in children's learning, has a profound impact on what happens in the Kindergarten classroom.

All children are competent, capable of complex thinking, curious, and rich in potential and experience. They grow up in families with diverse social, cultural, and linguistic perspectives. Every child should feel that he or she belongs, is a valuable contributor to his or her surroundings, and deserves the opportunity to succeed. When we recognize children as competent, capable, and curious, we are more likely to deliver programs that value and build on their strengths and abilities.

Families are composed of individuals who are competent and capable, curious, and rich in experience. Families love their children and want the best for them. Families are experts on their children. They are the first and most powerful influence on children's learning, development, health, and well-being. Families bring diverse social, cultural, and linguistic perspectives. Families should feel that they belong, are valuable contributors to their children's learning, and deserve to be engaged in a meaningful way.

Educators are competent and capable, curious, and rich in experience. They are knowledgeable, caring, reflective, and resourceful professionals. They bring diverse social, cultural, and linguistic perspectives. They collaborate with others to create engaging environments and experiences to foster children's learning and development. Educators are lifelong learners. They take responsibility for their own learning and make decisions about ways to integrate knowledge from theory, research, their own experience, and their understanding of the individual children and families they work with. Every educator should feel he or she belongs, is a valuable contributor, and deserves the opportunity to engage in meaningful work.

The Kindergarten Program flows from these perspectives, outlining a pedagogy that expands on what we know about child development and invites educators to consider a more complex view of children and the contexts in which they learn and make sense of the world around them. This approach may require, for some, a shift in mindset and habits. It may prompt a rethinking of theories and practices – a change in what we pay attention to; in the conversations that we have with children, families, and colleagues; and in how we plan and prepare.

The manner in which we interact with children is influenced by the beliefs we hold. To move into the role of co-learner, educators must acknowledge the reciprocal relationship they are entering: the child has something to teach us, and we are engaged in a learning journey together, taking turns to lead and question and grow as we encounter new and interesting ideas and experiences. The view of the child presented above recognizes the experiences, curiosities, capabilities, competencies, and interests of all learners.

Pedagogy and programs based on a view of children as competent and capable

Pedagogy is defined as the understanding of how learning happens and the philosophy and practice that support that understanding of learning. (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2007, p. 90)

When educators view children as competent and capable, the learning program becomes a place of wonder, excitement, and joy for both the child and the educator. (Saskatchewan Ministry of Education, 2008, p. 9)

Educators' beliefs about children are foundational to sound pedagogy and a high-quality learning program. Over the years, the image of children has evolved, and the cultural view – the one that is "shaped by the values and beliefs about what childhood should be at the time and place in which we live" (Fraser, 2012, p. 20) – has shifted. When educators believed that children were "empty vessels to be filled", programs could be too didactic, centred on the educator and reliant on rote learning, or they involved minimal interaction between children and educators; in either case, they risked restricting rather than promoting learning.

When programs are founded on the image of the child presented above and when educators apply knowledge and learning gained through external and classroom research, early learning programs in Ontario, including Kindergarten programs, can establish a strong foundation for learning and create a learning environment that allows all children to grow and to learn in their unique, individual ways.

Pedagogical approaches

The pedagogical approaches that work best for young children are similar to strategies that work for learners of all ages, from infancy to adulthood. Evidence from research and practice shows that these approaches are the most effective ways to nurture and support learning and development among both children and adult learners.

- Responsive relationships – Evidence from research and practice shows that positive interactions between teacher and student are the most important factor in improving learning (Hattie, 2008). An awareness of being valued and respected – of being seen as competent and capable – by the educator builds children's sense of self and belonging and contributes to their well-being, enabling them to be more engaged in learning and to feel more comfortable in expressing their thoughts and ideas.

- Learning through exploration, play, and inquiry – As children learn through play and inquiry, they develop – and have the opportunity to practise every day – many of the skills and competencies that they will need in order to thrive in the future, including the ability to engage in innovative and complex problem-solving and critical and creative thinking; to work collaboratively with others; and to take what is learned and apply it in new situations in a constantly changing world. (See the "Fundamental Principles of Play-Based Learning" in the following section, and Chapter 1.2, "Play-Based Learning in a Culture of Inquiry". )

- Educators as co-learners – Educators today are moving from the role of "lead knower" to that of "lead learner" (Katz & Dack, 2012, p. 46). In this role, educators are able to learn more about the children as they learn with them and from them.

- Environment as third teacher – The learning environment comprises not only the physical space and materials but also the social environment, the way in which time, space, and materials are used, and the ways in which elements such as sound and lighting influence the senses. (See Chapter 1.3, "The Learning Environment".)

- Pedagogical documentation – The process of gathering and analysing evidence of learning to "make thinking and learning visible" provides the foundation for assessment for, as, and of learning. (See Chapter 1.4, "Assessment and Learning in Kindergarten: Making Children's Thinking and Learning Visible".)

- Reflective practice and collaborative inquiry – Educators develop and expand their practice by reflecting independently and with other educators, children, and children's families about the children's growth and learning.

These pedagogical approaches, outlined in How Does Learning Happen?, are central to the discussion in Part 1 of this document. Throughout the document, they are understood to be foundational to teaching that supports learning in Kindergarten and beyond.

Fundamental principles of play-based learning

Global conversations and perspectives on learning from various fields – neuroscience, developmental and social psychology, economics, medical research, education, and early childhood studies – confirm that, among the pedagogical approaches described above, play-based learning emerges as a focal point, with proven benefits for learning among children of all ages, and indeed among adolescent and adult learners. The following fundamental principles have been developed to capture the recurring themes in the research on beneficial pedagogical approaches, from the perspective of play-based learning.

Fundamental principles of play-based learning

- Play is recognized as a child's right, and it is essential to the child's optimal development.

- The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child recognizes "the right of the child … to engage in play … appropriate to the age of the child" and "to participate freely in cultural life and the arts".

United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, Article 31,“Convention on the Rights of the Child” (Entry into force 2 September 1990). - Play is essential to the development of children's cognitive, physical, social, and emotional well-being. The Association for Childhood Education International (ACEI) recognizes play as necessary for all children and critical to children's optimal growth, learning, and development from infancy to adolescence.

J.P. Isenberg and N. Quisenberry, “A Position Paper of the Association for Childhood Education International – Play: Essential for All Children”. Childhood Education (2002), 79(1), p. 33. - Educators recognize the benefits of play for learning and engage in children's play with respect for the children's ideas and thoughtful attention to their choices.

- The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child recognizes "the right of the child … to engage in play … appropriate to the age of the child" and "to participate freely in cultural life and the arts".

- All children are viewed as competent, curious, capable of complex thinking, and rich in potential and experience.

- In play-based learning, educators honour every child's views, ideas, and theories; imagination and creativity; and interests and experiences, including the experience of assuming new identities in the course of learning (e.g., "I am a writer!"; "I am a dancer!").

- The child is seen as an active collaborator and contributor in the process of learning. Together, educators and learners plan, negotiate, reflect on, and construct the learning experience.

- Educators honour the diversity of social, cultural, and linguistic backgrounds represented among the children in the classroom, and take each child's background and experiences into account when interpreting and responding to the child's ideas and choices in play.

- A natural curiosity and a desire to explore, play, and inquire are the primary drivers of learning among young children.

- Play and inquiry engage, challenge, and energize children, promoting an active, alert, and focused state of mind that is conducive to learning.

- Children's choices in play are the best starting points for the co-construction of learning with the child.

- Educators respond to, challenge, and extend children's learning in play and inquiry by:

- observing;

- listening;

- questioning;

- provoking;

In education, the term “provoking” refers to provoking interest, thought, ideas, or curiosity by various means – for example, by posing a question or challenge; introducing a material, object, or tool; creating a new situation or event; or revisiting documentation. “Provocations” spark interest, and may create wonder, confusion, or even tension. They inspire reflection, deeper thinking, conversations, and inquiries, to satisfy curiosity and resolve questions. In this way, they extend learning. - providing descriptive feedback;

- engaging in reciprocal communication and sustained conversations;

- providing explicit instruction at the moments and in the contexts when it is most likely to move a child or group of children forward in their learning.

- The learning environment plays a key role in what and how a child learns.

- A learning environment that is safe and welcoming supports children's well-being and ability to learn by promoting the development of individual identity and by ensuring equity

Ensuring equity is one of the four goals outlined in the Ministry of Education’s Achieving Excellence: A Renewed Vision for Education in Ontario (2014a, p. 8), which states: “The fundamental principle driving this [vision] is that every student has the opportunity to succeed, regardless of ancestry, culture, ethnicity, gender, gender identity, language, physical and intellectual ability, race, religion, sex, sexual orientation, socio- economic status or other factors.” and a sense of belonging for all. - Both in the classroom and out of doors, the learning environment allows for the flexible and creative use of time, space, and materials in order to respond to children's interests and needs, provide for choice and challenge, and support differentiated and personalized instruction and assessment.

- The learning environment is constructed collaboratively and through negotiation by children and educators, with contributions from family and community members. It evolves over time in response to children's developing strengths, interests, and abilities.

- A learning environment that inspires joy, awe, and wonder promotes learning.

- A learning environment that is safe and welcoming supports children's well-being and ability to learn by promoting the development of individual identity and by ensuring equity

- In play-based learning programs, assessment supports the child's learning and autonomy as a learner.

- In play-based learning, educators, children, and family members collaborate in ongoing assessment for and as learning to support children's learning and their cognitive, physical, social, and emotional development.

- Assessment in play-based learning involves "making thinking and learning visible" by documenting and reflecting on what the child says, does, and represents in play and inquiry.

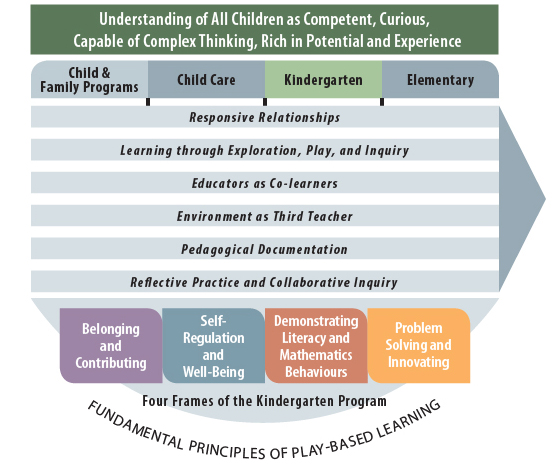

The four frames of the Kindergarten program

In the Kindergarten program, four "frames", or broad areas of learning, are used to structure thinking about learning and assessment.

The four frames align with the four foundational conditions needed for children to grow and flourish – Belonging, Well-Being, Expression, and Engagement. These foundations, or ways of being, are central to the pedagogy outlined in the early learning resource How Does Learning Happen? They are conditions that children naturally seek for themselves, and they apply regardless of age, ability, culture, language, geography, or setting.

Figure 2. The four frames of Kindergarten (outer circle) grow out of the four foundations for learning and development set out in the early learning curriculum framework (inner circle). The foundations are essential to children's learning in Kindergarten and beyond. The frames encompass areas of learning for which four- and five-year-olds are developmentally ready.

The four Kindergarten frames grow out of the four foundations for learning and development. The Kindergarten frames are defined more specifically to reflect the developmental and learning needs of children in Kindergarten and beyond.

The overall expectations (OEs) of the Kindergarten program are connected with the four frames (see The Overall Expectations, by Frame). An expectation is associated with the frame that encompasses the aspects of learning and development to which that expectation most closely relates. An expectation that addresses more than one aspect of learning may be connected with more than one frame

The four frames may be described as follows:

Belonging and contributing

This frame encompasses children's learning and development with respect to:

- their sense of connectedness to others;

- their relationships with others, and their contributions as part of a group, a community, and the natural world;

- their understanding of relationships and community, and of the ways in which people contribute to the world around them.

The learning encompassed by this frame also relates to children's early development of the attributes and attitudes that inform citizenship, through their sense of personal connectedness to various communities.

Self-regulation and well-being

This frame encompasses children's learning and development with respect to:

- their own thinking and feelings, and their recognition of and respect for differences in the thinking and feelings of others;

- regulating their emotions, adapting to distractions, and assessing consequences of actions in a way that enables them to engage in learning;

- their physical and mental health and wellness.

In connection with this frame, it is important for educators to consider:

- the interrelatedness of children's self-awareness, sense of self, and ability to self-regulate;

- the role of the learning environment in helping children to be calm, focused, and alert so they are better able to learn.

What children learn in connection with this frame allows them to focus, to learn, to respect themselves and others, and to promote well-being in themselves and others.

Demonstrating literacy and mathematics behaviours

This frame encompasses children's learning and development with respect to:

- communicating thoughts and feelings – through gestures, physical movements, words, symbols, and representations, as well as through the use of a variety of materials;

- literacy behaviours, evident in the various ways they use language, images, and materials to express and think critically about ideas and emotions, as they listen and speak, view and represent, and begin to read and write;

- mathematics behaviours, evident in the various ways they use concepts of number and pattern during play and inquiry; access, manage, create, and evaluate information; and experience an emergent understanding of mathematical relationships, concepts, skills, and processes;

- an active engagement in learning and a developing love of learning, which can instil the habit of learning for life.

What children learn in connection with this frame develops their capacity to think critically, to understand and respect many different perspectives, and to process various kinds of information.

Problem solving and innovating

This frame encompasses children's learning and development with respect to:

- exploring the world through natural curiosity, in ways that engage the mind, the senses, and the body;

- making meaning of their world by asking questions, testing theories, solving problems, and engaging in creative and analytical thinking;

- the innovative ways of thinking about and doing things that arise naturally with an active curiosity, and applying those ideas in relationships with others, with materials, and with the environment.

The learning encompassed by this frame supports collaborative problem solving and bringing innovative ideas to relationships with others.

In connection with this frame, it is important for educators to consider the importance of problem solving in all contexts – not only in the context of mathematics – so that children will develop the habit of applying creative, analytical, and critical thinking skills in all aspects of their lives.

What children learn in connection with all four frames lays the foundation for developing traits and attitudes they will need to become active, contributing, responsible citizens and healthy, engaged individuals who take responsibility for their own and others' well-being.

Supporting a continuum of learning

The Ontario Early Years Policy Framework envisages early years curriculum development that helps children make smooth transitions from early childhood programs to Kindergarten, the primary grades, and beyond. All of the elements discussed above – a common view of children as competent and capable; coherence across pedagogical approaches; a shared understanding of the foundations for learning and development, leading into the four frames of the Kindergarten program; and the fundamental principles of play-based learning – contribute to creating more seamless programs for children, families, and all learners, along a continuum of learning and development.

The vision of the continuum is illustrated in How Does Learning Happen? (p. 14). That graphic is adapted here to depict the continuum from the perspective of Kindergarten.

Figure 3. Pedagogical approaches that support learning are shared across settings to create a continuum of learning for children from infancy to age six, and beyond.

The organization and features of this document

This document is organized in four parts:

- Part 1 outlines the philosophy and key elements of the Kindergarten program, focusing on the following: learning through relationships; play-based learning in a culture of inquiry; the role of the learning environment; and assessment for, as, and of learning through the use of pedagogical documentation, which makes children's thinking and learning visible to the child, the other children, and the family.

- Part 2 comprises four chapters, each focused on "thinking about" one of the four Kindergarten frames. Each chapter explores the research that supports the learning focus of the frame for children in Kindergarten, outlines effective pedagogical approaches relevant to the frame, and provides tools for reflection to help educators develop a deeper understanding of learning and teaching in the frame.

- Part 3 focuses on important considerations that educators in Kindergarten take into account as they build their programs, and on the connections and relationships that are necessary to ensure a successful Kindergarten program that benefits all children.

- Part 4 sets out the learning expectations for the Kindergarten program and provides tools for supporting educators' professional learning and reflection. The list of the overall expectations, indicating the frame or frames to which each expectation is connected, is presented in Chapter 4.2. Chapters 4.3 through 4.6 set out the overall expectations and conceptual understandings by frame, along with "expectation charts" for each frame. The expectation charts provide information and examples to illustrate how educators and children interact to make thinking and learning visible in connection with the specific expectations that are relevant to the particular frame.

- The appendix is a chart that lists all of the overall expectations, with their related specific expectations, and indicates the frame(s) with which each expectation is associated.

The document is designed to guide educators as they adopt the pedagogical approaches that will help the children in their classrooms learn and grow. It recognizes the transformational nature of these approaches, as well as the benefits of collaborative reflection and inquiry in making the transition from more traditional pedagogies and program planning approaches. To support and inspire educators as they reflect on and rethink traditional beliefs and practices and apply new ideas from research and proven practice, this document offers a variety of special features:

- Educator Team Reflections and Inside the Classroom: Reflections on Practice – Reflections and scenarios provided by educators from across Ontario, reflecting situations that arose in their own classrooms during the implementation of Kindergarten.

- Professional Learning Conversations – Interspersed throughout the expectation charts in Part 4 and focused on learning in relation to the overall and specific expectations, these conversations illustrate pedagogical insights gained through collaborative professional learning among educators across Ontario.

- Questions for Reflection – Questions designed to stimulate reflection and conversation about key elements and considerations related to the Kindergarten program.

- Misconceptions – Lists of the common misconceptions that abound about children's learning through play and inquiry and that are addressed throughout the chapters of this document.

- Links to Resources – Active links to electronic resources, including videos and web postings, that illustrate pedagogical approaches discussed in the text.

- Internal Links – Active links to related sections or items within The Kindergarten Program.

We're moving content over from an older government website. We'll align this page with the ontario.ca style guide in future updates.

1.2 Play-based learning in a culture of inquiry

1.2 Play-based learning in a culture of inquiry robertallisonChildren are constantly engaged in making meaning of their world and in sharing their perceptions. Play is an optimal context for enabling children to work out their ideas and theories and use what they already know to deepen their understanding and further their learning. Innately curious, children explore, manipulate, build, create, wonder, and ask questions naturally, moving through the world in what might be called an "inquiry stance". Educators observe and document the children's thinking, ideas, and learning; interpret and analyse what they have noticed; and express their own thinking and wondering as they interact with the children. In a Kindergarten classroom, the educators adopt an inquiry stance along with the children, and a culture of inquiry characterizes the learning environment.

Inquiry is an integral part of certain disciplines. For example, inquiry processes and skills are central to science and technology. However, in the Kindergarten program, inquiry is not a set of processes and skills but a pervasive approach or "stance", a habit of mind that permeates all thinking and learning throughout the day. It is not limited to a subject area or topic, a project, or a particular time of day. It is not an occasional classroom event, and it is not an approach appropriate for only some children. As noted in the curriculum policy document for each discipline in the Ontario curriculum, inquiry is "at the heart of learning in all subject areas". Educators use their professional knowledge and skills to co-construct inquiry with the children – that is, to support children's learning through play, using an inquiry approach.

Play as the optimal context for learning: Evidence from research

Play nourishes every aspect of children's development. … Play develops the foundation of intellectual, social, physical, and emotional skills necessary for success in school and in life. It "paves the way for learning". (Canadian Council on Learning, 2006, p. 2)

Play is a vehicle for learning and rests at the core of innovation and creativity. It provides opportunities for learning in a context in which children are at their most receptive. Play and academic work are not distinct categories for young children, and learning and doing are also inextricably linked for them. It has long been acknowledged that there is a strong link between play and learning for young children, especially in the areas of problem solving, language acquisition, literacy, and mathematics, as well as the development of social, physical, and emotional skills (NAEYC, 2009; Fullan, 2013; Ontario Ministry of Education, 2014c).

Young children actively explore their environment and the world around them through play. When children are exploring ideas and language, manipulating objects, acting out roles, or experimenting with various materials, they are engaged in learning through play. Play, therefore, has an important role in learning and can be used to further children's learning in all areas of the Kindergarten program.

How do children learn through play?

In its "Statement on Play-Based Learning", the Council of Ministers of Education, Canada (CMEC), recognizes the educational value of play as follows:

The benefits of play are recognized by the scientific community. There is now evidence that neural pathways in children's brains are influenced by and advanced in their development through the exploration, thinking skills, problem solving, and language expression that occur during play.

Research also demonstrates that play-based learning leads to greater social, emotional, and academic success. Based on such evidence, ministers of education endorse a sustainable pedagogy for the future that does not separate play from learning but brings them together to promote creativity in future generations. In fact, play is considered so essential to healthy development that the United Nations has recognized it as a specific right for all children. …

Given the evidence, the CMEC believes in the intrinsic value and importance of play and its relationship to learning. Educators should intentionally plan and create challenging, dynamic, play-based learning opportunities. Intentional teaching is the opposite of teaching by rote or continuing with traditions simply because things have always been done that way. Intentional teaching involves educators' being deliberate and purposeful in creating play-based learning environments – because when children are playing, children are learning.

(CMEC, 2012)

Read:

The process through which learning happens in play is complex. Educators continually develop and deepen their understanding of that process through professional learning and classroom observation, interpretation, and analysis. To be effective, educators depend on their nuanced understanding of the many ways in which children learn and develop and how children's grasp of concepts is revealed during play (Trawick-Smith & Dziurgot, 2010). Educators also realize how critical their role is in helping to consolidate and further children's learning in play by making their learning visible to the children, as well as to their families.

Educator team reflections

It was important for our educator teams to understand and express our beliefs and have courageous conversations about play-based learning. Even though we all believed that play was important, there was a range of opinion as to what it meant. Some of us had training that said: When children are at play, adults should be "hands off". Others had experienced play as what the children do while the teacher is busy working with ("teaching") a small group. We studied the description that was offered at a professional learning session on the Kindergarten program and began to rethink play as a critical context for learning. We all agreed to study our role in play.

We had to rethink what was meant by "play". We believed the activities we used to plan were play. Every child had to complete a "cookie-cutter" craft – but the activity never really met the children's needs. They would either rush through it, or we would end up coaxing them to complete the craft – otherwise, we would have to explain to their parents why they hadn't completed it! At first, we worried about removing these activities, but when we began to offer the children materials so they could choose how to represent their thinking, we realized that they were much more capable as artists than we had thought. We are amazed every day at the complex pieces they are creating.

Kindergarten classrooms make use of play and embed opportunities for learning through play in the physical environment (ELECT, 2007, p. 15; see also Chapter 1.3, "The Learning Environment"). The learning experiences are designed by the educators to encourage the children to think creatively, to explore and investigate, to solve problems, self-regulate, and engage in the inquiry process, and to share their learning with others.

Educator team reflection

I was uncertain of my role in the children's play – I thought it was my role to set up play activities and then supervise and react, but I worried that I might take over the play if I interacted with the children. Now, we are learning about documentation and figuring out our role. We find time in the day – and have made it a priority – to study our documentation together. We have a deeper understanding of the children's learning, and we are really thinking together about how we might respond, extend, and challenge the children's thinking … and our own!

Play-based learning: The connections to self-regulation

When children are fully engaged in their play, their activity and learning … [are] integrated across developmental domains. They seek out challenges that can be accomplished … Through play, children learn trust, empathy, and social skills. (Pascal, 2009a, pp. 8‑9)

Vygotsky (1978) connects socio-dramatic play ("pretend" play) to children's developing self-regulation. During socio-dramatic play, children naturally engage in learning that is in their "zone of proximal development" – in other words, learning that is at the "edge" of their capacities. Evidence may be seen in various play contexts in the classroom – children may be noticing for the first time that they can influence how water moves through a tube, that their shadow moves when they move, or how it feels to move a paintbrush over a canvas. As they notice and build on their insights, they are regulating their own learning.

In socio-dramatic play, language becomes a self-regulatory tool. Children's private speech, or self-talk, is a mode through which they shift from external regulation (e.g., by a family member or educator) to self-regulation. Children begin to assimilate adult prompts, descriptions, explanations, and strategies by incorporating them into their self-talk. As they integrate the language they have heard into their own private speech, they are activating complex cognitive processes such as attention, memory, planning, and self-direction (Shanker, 2013b). Participants in socio-dramatic play communicate with each other using language and symbolic gestures to describe and extrapolate from familiar experiences, and to imagine and create new stories. Socio-dramatic play supports children's self-regulation and increases their potential to learn as they engage with the people and resources in their environment (Pascal, 2009a).

View: Video clips

- "A play-based approach to learning is important in developing children's self-regulation"

- "Play-based learning creates a passion for learning"

- "Rethinking and repeating supporting self-regulation – one educator team's reflection"

The inquiry approach: Evidence from research

Research suggests that students are more likely to develop as engaged, self-directed learners in inquiry-based classrooms (Jang, Reeve, & Deci, 2010).

Inquiry allows students to make decisions about their learning and to take responsibility for it. [Educators] create learning contexts that allow children to make decisions about their learning processes and about how they will demonstrate their learning. They encourage collaborative learning and create intellectual spaces for students to engage in rich talk about their thinking and learning. They create a classroom ethos that fosters respect for others' ideas and opinions and encourages risk-taking. ... Collectively, these actions lead to a strong sense of student self-efficacy. (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2011, p. 4)

Asking questions and making sense of information to expand understanding are at the core of all inquiry. Through its focus on an inquiry approach, the Kindergarten program promotes the development of higher-order thinking skills by capitalizing on children's natural curiosity, their innate sense of wonder and awe, and their desire to make sense of their environment. An inquiry approach nurtures children's natural inquisitiveness. As educators give children opportunities to seek answers to questions that are interesting, important, and relevant to them, they are enabling them to address curriculum content in integrated, "real world" ways and to develop – and practise – the higher-order thinking skills and habits of mind that lead to deep learning.

Read:

- "Getting Started with Student Inquiry", Capacity Building Series (October 2011)

- "What Educators Are Learning about Learning in an Inquiry Stance", K to 2 Connections (August 2013)

View: Video clips

- "What does inquiry-based learning look like and sound like? How are educator teams repeating, removing, and rethinking their theme-based planning and moving to inquiry?"

- "Reflections from another FDELK team on moving from themes to inquiry. What did they notice?"

- "How are educator teams repeating, removing and rethinking their inquiry-based planning?"

Play-based learning in an inquiry stance

As noted above, educators in a Kindergarten classroom adopt an inquiry stance – a mindset of questioning and wondering – alongside the children, to support their learning as they exercise their natural curiosity. In addition to joining the children in inquiry, educators, as "classroom researchers", wonder and ask questions about the children and the children's learning (e.g., "Why this learning for this child at this time and in this context?") and about the impact of their interventions on children's learning and growth in learning (e.g., "What will be the impact on the learning of these children if I intervene in their conversation in this way at this time?", "How might changing the way we use the tables in the classroom affect the way the children collaborate?"). Being in an inquiry stance is critical to creating the conditions required for inquiry learning.

As educators question and wonder along with the children, they bear in mind the intention for learning – which, in any given context, will involve one or more of the overall expectations (OEs) set out in this document (see Chapter 4.2). The educators do not plan lessons based on predetermined topics at predetermined times (e.g., topics based on the calendar, such as Mother's Day in May, Thanksgiving in October), and they do not develop lessons or activities around the "nouns" that the children happen to use (e.g., rocks, trains, tadpoles), as was often done in the past. Instead, inquiries evolve out of reciprocal questioning and wondering. As the children express their thinking, educators think about questions they can ask that will further provoke children's thinking and continue to stimulate their curiosity and wonder.

For example, a child might bring some tadpoles to school. As the child voices questions, ideas, facts, and opinions about them, other children who are interested in the tadpoles might join in. The educators engage the children about their questions and ideas, probing for more details and clarification from them. Rather than providing information about the tadpoles, they wonder out loud about how, together, they might find answers to some of the questions. One of the children might express the idea that tadpoles turn into frogs. Through a probing question such as "How could we find out if that's what happens?", the educators can elicit ideas, and the group might decide to observe the tadpoles over a period of time and to record what they observe (OE13). Together, the educators and the children consider the many ways in which the children could represent their observations and ideas (e.g., in a drawing or a model, or by acting them out) and the kinds of tools and equipment they will need to do this. They might also discuss the care they will need to provide for the tadpoles. At this point, other children might be invited to be part of the inquiry as well. The educators might probe to find out what bigger questions underlie the children's interest – what does it mean to develop? To transform? What is happening on the inside of the tadpole while it changes on the outside? The educators might also choose to provoke further inquiry by providing opportunities for the children to explore other similar kinds of changes or stages of life that happen – for example, in seeds, in eggs, and even in humans. Once the inquiry is under way, the observations would need to be recorded – and this would become a purpose for writing and an opportunity for the children to learn about an important element of the writing process (OE1 and OE10).

Using questions to promote inquiry and extend thinking

In response to children's questions and ideas, educators pose questions such as:

- What do you think?

- What would happen if …?

- I wonder why your measurement is different from Jasmine's?

- How are you getting water from one container to another?

- How could you show your idea? How can we find out if your idea works?

- I wonder if we could make our own marble run?

Children ask questions that lead to inquiry. For example:

- How can this car go faster down the ramp?

- Where are the biggest puddles?

Children communicate ideas and ask further questions while they are experimenting and investigating. They might describe materials they are using, indicate a problem they are having, or ask a question such as "I wonder what would happen if I ...?" They begin to listen to their peers and may offer suggestions to them. Through these interactions and as the educators extend children's thinking through their questions and observations, children also learn to make predictions and draw conclusions:

- "I think if I use a bigger block on the bottom, my tower won't break. See, it worked! I used this big block and it didn't fall over."

- "I thought it would take six footsteps, but it took ten."

The educators engage with the children in inquiries that enable the children to explore their questions and wonderings as co-learners with the educators. The educators offer provocations that build on the children's thinking or invite the children to engage in new ways of learning.

Further to the example about tadpoles above, the educators might point out to the children that scientists investigate things they are interested in, and that the children now have an opportunity to "be" scientists as well. The educators will have placed hand lenses and recording materials at a table with the tadpoles, pointing out to the children that they are using the same tools that scientists use. They might also mention that the children are using the same processes that scientists use (e.g., observing, wondering, asking questions and generating theories, communicating, working together). As the children conduct their investigation, the educators observe and document what they say and do. The educators confer about the documentation and then reflect on it with the children, negotiating what materials the children might add or take away in order to further test their theories about the tadpoles and build on their thinking.

For more information about pedagogical documentation, see Chapter 1.4, "Assessment and Learning in Kindergarten".

View: Video clips

- "What does it look like and sound like to co-construct inquiry with the children? Reflections on inquiry: Observations and making learning visible"

- "What does it look like and sound like to co-construct inquiry with the children? Listening in on a classroom inquiry"

Questions to guide video viewing

- What could the conversation be while watching the video (e.g., recalling a moment when you have rethought some aspect of your program)?

- How did the learning change when the educators trusted their judgement and rethought their intervention?

The following chart outlines the elements of the inquiry process in the Kindergarten classroom, describing the actions of both the children and the educators.

The Inquiry Process in the Kindergarten Classroom

| Elements of the child's inquiry process | When children are engaged in the inquiry process, they: | When educators are modelling or supporting the inquiry process, they: |

|---|---|---|

| Initial engagement – noticing, wondering, playing |

|

|

| Exploration – exploring, observing, questioning |

|

|

| Investigation – planning, using observations, reflecting |

|

|

| Communication – sharing findings, discussing ideas |

|

|

Questions for reflection: How well are we supporting the children's inquiry?

- How does inquiry evolve in both our indoor and outdoor classroom?

- What does inquiry in our indoor and outdoor classroom look like/sound like?

- Is there sufficient time for the children to engage deeply in play and inquiry? How do we know?

- How will we communicate our play-based inquiry process to any educator who stands in for us in the classroom (e.g., our planning-time teacher)?

- What is it about our learning environment that makes it conducive to inquiry and supports inquiry-based learning?

- Does this material lead to rich and engaging inquiries? What makes it stimulating?

Read:

The critical role of the educator team: Co-constructing inquiry and learning

[W]e must abandon our idea of a static, knowable educator and move on to a view of an educator in a state of constant change and becoming. The role of the educator shifts from a communicator of knowledge to a listener, provocateur, documenter, and negotiator of meaning. (Pacini-Ketchabaw et al., 2009, p. 103)

The examples in the previous section illustrate how educators, in their interactions with the children, constantly engage in a creative collaboration with them to co-construct thinking and learning. The process can be summarized as follows:

As educators collaborate with the children to:

- formulate questions,

- select materials,

- stimulate and support creativity,

- think aloud about various perspectives and interpretations,

- think aloud about multiple possibilities or solutions,

- solve problems, and

- document thinking and learning,

they intentionally and purposefully:

- listen,

- observe,

- document,

- analyse documentation, considering a range of possible meanings and perspectives and making connections to the overall expectations, and

- provide feedback through questions and prompts that effectively extend thinking and learning.

Educators strive to internalize the overall expectations, reviewing the conceptual understandings that accompany them to see the broader ideas, skills, and understandings that flow from them. Educators keep the overall expectations in mind as they interact with the children in play and inquiry.

The educators use their observations and documentation of the children's thinking and learning to seek multiple perspectives – including those of the children themselves, the parents and other family members, and colleagues. The information gleaned from these various perspectives can provide greater insight into the children's thinking and learning, enabling the educators to make the kinds of connections and pose the kinds of questions and prompts that will most effectively support and extend the children's learning.

As the educators interact with the children, they respond to, clarify, challenge, and expand on their thinking. They negotiate the selection of a rich variety of materials and resources for them to use, and co-construct the children's inquiry with them.

As children move naturally from noticing and wondering about the objects and occurrences around them to exploring, observing, and questioning in a more focused way, the educators document their thinking, what they are wondering about, their theories, and the ideas that pique their interest. They interpret and analyse the documentation to support their own inquiry and learning about how the children learn. Their analysis, which focuses on how the children's thinking and learning relates to the overall expectations, informs the choices educators will make about how to further challenge and extend the children's thinking and learning. It also serves as a guide to the level and type of support each child needs. The educators' documentation and analysis make children's thinking and learning visible and inform the path that educators take to support individual children's learning.

For further information, see Chapter 1.4, "Assessment and Learning in Kindergarten".

Figure 4. This graphic depicts the interdependent roles of children and educators in play-based learning. It identifies the various ways in which children and educators engage throughout the day, showing their roles in the co-construction of learning.

Questions for reflection

As we observe and document, then review and analyse our documentation to determine next steps for a particular child's or group of children's learning, we ask ourselves questions such as the following:

- How can we find out what this child might be thinking?

- Why have we chosen this learning for this child at this time in this context?

- How is this child constructing knowledge with other children? In what ways does the child participate and contribute?

- How is this child's approach to a problem different now from what it was earlier?

- How does the evidence we've gathered help us determine the next steps in learning for the child?

Literacy in an inquiry stance

- How are the children using letters in their play?

- What do they know about their names?

- How do they approach text in a book? How do they respond to text that they see in the environment?

- How do they use language when they negotiate, debate, describe, order, count, predict, make suppositions, or theorize?

- How do they use drawing and/or writing (graphic representation) to capture memory, describe experiences, represent thinking, negotiate, list, and label?

- How do they bring social narratives into their play?

- How do they bring retells and recounts into their play?

Mathematics in an inquiry stance

- How do the children reveal their knowledge and thinking about quantity relationships?

- What does the way they use materials/manipulatives reveal about their mathematical thinking?

- How do they think about measurement and about the ways we use it in various familiar contexts? How do they reveal their thinking about measurement?

- What do they think about what makes a pattern?

- What do they think about why we collect data (e.g., to inform us, to help us make decisions about something)? What are their ideas about how to collect data (e.g., taking surveys)?

- How do they reveal their thinking about shapes and spatial relationships?

View: Video clips

How does the inquiry approach differ from theme-based or unit planning?

Traditional planning models asked educators to develop "themes" or teaching units composed of several lesson plans with stated objectives, the relevant program/curriculum learning expectations, and materials lists. Kindergarten programs were traditionally structured around monthly themes related to seasonal events and celebrations, and resource books supporting such themes have provided related activities that adults believed would appeal to early learners. Such planning models and associated resources, all based on adult perceptions of children's interests and learning, have been shown to have a negative effect on children's engagement (Edwards, Gandini, & Forman, 1998; Wells, 2001).

Educator team reflection

At a recent professional learning session, I began to feel uncomfortable about how closely one of the planning models we were asked to critique aligned with the plans I had been using for several years. As our group began to reflect, we wondered if the way we had always planned made sense from the children's point of view. I reflected that I had often felt somewhat limited by plans that were based on the monthly calendar. I had always assumed that the children were interested in the monthly topics I had chosen – but had I ever asked them what they were interested in? And were they really able to think deeply and concretely about topics outside their direct experience, such as polar bears and the rainforest?

Traditional planning versus an inquiry-based approach

| Traditional planning | Inquiry-based approach |

|---|---|

|

|

Misconceptions about play-based learning

- That play-based learning that "follows the children's lead" means that the educators do not take an active role in designing children's learning experiences as they collaborate with them in play or that they do not intentionally and purposefully inject planned opportunities for challenging and extending children's thinking and learning

- That play happens after or apart from learning

- That literacy and mathematics are neglected in a play-based context

- That play does not involve group work

- That play is always hands-on and physically active

- That play is either teacher-initiated or child-initiated (rather than being a fluid, negotiated engagement)

Misconceptions about learning and teaching in an inquiry stance

- That the educators listen for every topic the children are interested in and use each one as a topic of inquiry, or that they pursue all of the fleeting and ever-changing interests of the children

- That inquiry should begin with or be limited to topics found in non-fiction texts

- That the educators' role is to pick a broad topic (e.g., forest animals) and have the children select some aspect of the topic to explore (e.g., a particular animal)

- That only the children can generate ideas for inquiry, provoke thinking, or ask questions

- That inquiry involves a project or is conducted at a particular time in the day

- That the children determine what they will learn

Communicating with parents and families about play-based learning

Play-based learning supports growth in the language and culture of children and their families. (CMEC, 2012)

Play-based learning is the foundation of the Kindergarten program in Ontario. The concept of learning through play means different things to different people, especially to the parents and families of the children. It is therefore important for educators to have a clear understanding of play-based learning in the Ontario context, in order to be able to explain it to families, colleagues, and community partners. A shared understanding of how learning takes place through play can encourage family members and community partners to support play at home, and in community settings as well, and can help expand children's opportunities for play and learning.

See "Fundamental Principles of Play-Based Learning", in Chapter 1.1, "Introduction".

Family members want to understand how their children develop and learn. They normally welcome and benefit from educators' observations and information about how to support their children's learning. When speaking informally to families, and during classroom visits, educators can make the links between play and learning by sharing their observations in the moment. For example:

Amalla is learning about symmetry as she builds with the blocks today. Let's ask her to tell us what she notices about her structure.

When he was playing a card game with some of the other children, Jerome learned about taking turns.

Families also have valuable insights into their own children. When educators foster a more reciprocal relationship with families, both educators and families will have a more complex understanding of the children.

Children communicate and represent their learning with one another and with the educators in the context of their play and inquiry. The educators also provide more formal opportunities – for example, in child-led family conferences – for children to share their learning with their families through the documentation they and the educators have created, shared, and discussed.

View: Video "One parent's reflection on how learning is made visible through documentation"

The following parent information sheets are available to support educators' conversations with families and other partners about play- and inquiry-based learning:

- "The Power of Play-Based Learning"

- "Learning through Inquiry"

These resources are intended to supplement face-to-face conversations, not to replace them.

We're moving content over from an older government website. We'll align this page with the ontario.ca style guide in future updates.

1.3 The learning environment

1.3 The learning environment robertallisonThe learning environment is often viewed as "the third teacher"

A classroom that is functioning successfully as a third teacher will be responsive to the children's interests, provide opportunities for children to make their thinking visible, and then foster further learning and engagement. (Fraser, 2012, p. 67)

In Kindergarten the classroom environment is thoughtfully designed to invite, provoke, and enhance learning, and to encourage communication, collaboration, and inquiry. The space, with all the objects in it, including the various materials and resources for learning, is created and arranged as the children's learning process unfolds – it is constantly being negotiated by and with the children. This fluid, inclusive, and dynamic social space evolves, in part, as children express their thinking and wonderings and as ideas pique their interest. The educators' anticipation and recognition of the children's learning needs throughout the day and over time, based on their observations and analysis (assessment for learning), also drive the collaborative creation of the environment. In addition, the educators' practice of discussing, displaying, and sharing the children's work as well as documenting the children's learning through photographs, transcripts, and video clips – that is, the practice of making the children's learning visible – contributes to the creation of a learning environment that reflects and helps extend the children's interests and accomplishments.

Read: Karyn Callaghan, The Environment Is a Teacher (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2013)

View: Video clips

- "A new perspective"

- "Questioning our assumptions"

- "Rethinking the space"

- "Investigating the natural world"

Rethinking the learning environment

We need to think about creating classroom environments that give children the opportunity for wonder, mystery and discovery; an environment that speaks to young children's inherent curiosity and innate yearning for exploration is a classroom where children are passionate about learning... (Heard & McDonough, 2009, p. 2)

Educators plan and begin to create the learning environment before the children arrive in the classroom, using their understanding of children, of their development, and of how they learn, and looking at the space from a child's perspective. They place materials and resources where children can see them and ensure that children have plenty of light and a view of (and if possible, access to) the outdoors. They consider how to create an environment that will support children's learning and accommodate a diversity of choices and needs in terms of space, time, and the use of materials.

Before the children arrive in the classroom: Sample strategies from educators

- Take photographs of the room before making changes to support learning.

- Set the room up for learning. Arrange the tables to accommodate small groups, in various places around the classroom, rather than in cafeteria-style rows.

- Consider the space from a child's perspective. What do the children see from their height?

- Create areas for different kinds of learning and play. Try to make them versatile, to allow for purposeful learning and conversation.

- Think about the organization of materials and the kind and quantity of materials the children can access.

- Select and arrange materials and resources in ways that invite children to explore and that provoke learning but that do not overstimulate or overwhelm.

- Take "after" photographs. The images will help you see how the children's play and learning are affected by the changes.

Questions for reflection: How can we incorporate considerations about space and time in our learning environment design?

In what ways can we:

- organize spaces to make them "dynamic" – that is, to ensure that they can be changed quickly and easily to meet children's varying needs, and their changes in focus, through the course of the day?

- organize and use the space creatively, efficiently, and flexibly to accommodate multiple purposes, such as brief large-group meetings and opportunities for small-group and individual work?

- ensure that the learning environment supports learning for all children, accommodating a range of diverse needs and learning styles?

- anticipate how the organization of the space itself – the different areas for learning, the availability of open spaces – might invite imaginative play and provoke thinking and learning among the children?

Thinking about time and space

Kindergarten educators carefully consider how the use of time and space affects the children's learning. At the beginning of the year, the educators work collaboratively to set the classroom up for learning and to plan the "flow of the day". They work around daily school schedules (e.g., times for gym, lunch, recess, and library) in order to provide as much uninterrupted time as possible for children's play and inquiry, both in and out of doors, and to minimize transitions (see "A Flexible Approach to Learning: The Flow of the Day", in Chapter 3.1, "Considerations for Program Planning"). After the plan has been devised, it is adjusted in collaboration with the children, as necessary, to meet the children's changing needs. Educators strive for fluid and flexible plans in each instance, so that opportunities to respond to the children and to co-create with them can be readily accommodated.

Thinking about materials and resources