Purpose, benefits and considerations

ISSN 1198-712X, Published March 2022

Overview

Livestock guardian dogs (LGDs) have been used to protect livestock from predators for thousands of years

This fact sheet reviews the potential economic benefits and considerations of using LGDs as part of a predation mitigation strategy.

These companion fact sheets provide further information for producers seeking to add LGDs to their operation:

In 2011, 37% of respondents to an Ontario sheep producer survey reported using LGDs

The LGDs work to reduce predation in three ways

- territorial exclusion — presence of LGDs and their scent deters predators from entering territory

footnote 5 - disruption — aggressive behaviours such as barking and posturing discourage the predator from approaching the flock

- confrontation — physically engaging the predator

Benefits and considerations

There are many potential benefits of using LGDs as part of a predation mitigation strategy, but it’s important to weigh these benefits against potential challenges. In many producer surveys in the U.S., Canada and Australia, most respondents have indicated that they view their LGDs as an asset to their operation

Livestock guardian animals are only one aspect of a predation mitigation strategy. The use of other tools including hunting, trapping, deterrents and management practices are all important as part of a comprehensive predation mitigation strategy. The OMAFRA fact sheet Tools for mitigating losses due to coyote predation provides more detail.

Potential benefits

- increases the number of marketable lambs and kids and breeding stock replacements

- proactively rather than reactively mitigates predation

footnote 1 - decreases reliance on lethal control measures (such as hunting and trapping)

footnote 8 - reduces public concern for conflicts between livestock producers and wildlife

- reduces disease transmission from predators to the herd or flock

footnote 1 - reduces non-predatory wildlife consumption of pasture grass

footnote 1 - maintains effectiveness longer than other non‑lethal measures

footnote 7 - reduces producer labour and stress

footnote 8

Considerations

- may not be cost-effective for small herds or flocks

- may not be cost-effective if predation rates are low

- requires considerable labour and time for training and care of LGDs, which not all producers and staff enjoy

- require more specialized care than other guardian animals (donkeys, llamas), which can normally be managed as part of the flock or herd

- may cause complaints (such as barking or roaming) in populated areas

- creates a public safety concern if dogs are roaming (such as motor vehicle accidents, potential for injuring humans or pets)

- may cause conflict with the public due to misunderstandings about the use of LGDs and their needs

Stocking rates

A general rule of thumb is that 1 LGD is needed per 100 ewes or does in the operation. However, the ideal stocking rate for LGDs will depend on several factors

- number of stock to be guarded

- predation pressure and species

- maximum acceptable predation rate (no predation or minimum kills)

- terrain, amount of cover and the location of the pasture (for example, flat versus hilly, level of tree cover)

- number of ewe or doe groups in the operation and the distance between them

- dog confinement versus ability to free roam between pastures

- use of other predation strategies

- strength of flocking behaviour of the sheep

- effectiveness of individual dogs (age, training)

- personalities of individual dogs and dog-to-dog conflicts

In a large study of the effectiveness of LGDs in Australia, Van Bommel and Johnson reported that if more than 100 sheep or goats were protected per dog, the stock may spread out and make it difficult for the LGD to supervise

It’s recommended that even small operations (<100 ewes or does) have two LGDs to ensure that the flock or herd is protected if one of the LGDs is removed from the job (due to injury, death, female in heat or with puppies or other). Larger operations may also be able to exceed this stock per dog rate to reduce costs. In the Australian study, the average number of LGDs was 2 dogs for 100 stock, 4 dogs for 1,000 stock and 9 dogs for 10,000 stock

Expected costs

The costs associated with an LGD can be broken into three categories: purchase, annual care and labour. The costs of purchasing an LGD will vary considerably, but purchase costs reported in literature have ranged from about $500–$1,200. Listing prices in Ontario have been somewhat higher recently, ranging anywhere from $800–$1,600+. In addition to the purchase cost, first-year care costs for puppies include 2 to 3 veterinary visits for vaccinations and possibly the cost of spaying or neutering. These additional first-year costs may range from $200–$1,000+.

Annual care costs for mature animals are about $500–$700 for mid-priced kibble and $200–$300 for routine veterinary work. This does not include any emergency veterinary care. Therefore, approximately $700 to $1,000 should be budgeted for the annual care of each LGD.

It has been reported that producers spend an average of 7.5–10 hours per month (ranging from 0–30 hours) training, feeding and working with each LGD

Economic benefits

The direct economic benefits of LGDs are typically quantified by the value of livestock they prevent from being predated, but it can be more difficult to account for their indirect benefits

LGDs have been found to reduce rates of predation by 11%–100%, and roughly 70% on average

Evaluating cost-effectiveness

To be a cost-effective predation mitigation tool, LGDs must provide benefits, both economic and otherwise (such as peace of mind), that outweigh their purchase and care costs. Coppinger and Coppinger (2014) were quoted with saying

Are guarding dogs 100% successful at protecting livestock? Of course not, but they would not have survived as flock guardians had they not been cost-effective.

Nevertheless, LGDs may not be cost-effective for all operations

- current rate of predation

- size of flock or herd

- effectiveness of LGDs (% reduction in predation)

- longevity of LGDs

- value of the livestock

- cost and feasibility of other control measures

The next sections illustrate the impact of a few of these factors on the cost-effectiveness of LGDs as part of a predation mitigation strategy. The following assumptions were made in these calculations:

- The cost of purchasing and caring for an LGD puppy for the first-year totals $2,000, and annual care costs thereafter are $700 per dog.

- On average, LGDs will be effective for 5 years of service after reaching maturity.

- The use of LGDs reduces rates of predation by an average of about 70%

footnote 9 , but initial rates of predation will vary across operations. - The fair market value (FMV) calculation used in the Ontario Wildlife Damage Compensation Program for unweaned lambs (FMV = market price of an 80-lb lamb sold in the 80–94-lb price category at 12 weeks), with corresponding deductions for younger lambs, was used to estimate the value of a lamb.

- Example annual flock has a 200% lambing percentage, with an in-season conception rate of 90%, and 1% of all lambs are born stillborn (99% born alive).

Impact of LGD longevity

The cost-effectiveness of LGDs is strongly related to their longevity on-farm. The more years an LGD is in service, the more years the purchase price and costs during the unproductive adolescent phase can be distributed over. This reduces the number of lambs that would need to be saved per year to be an economic asset.

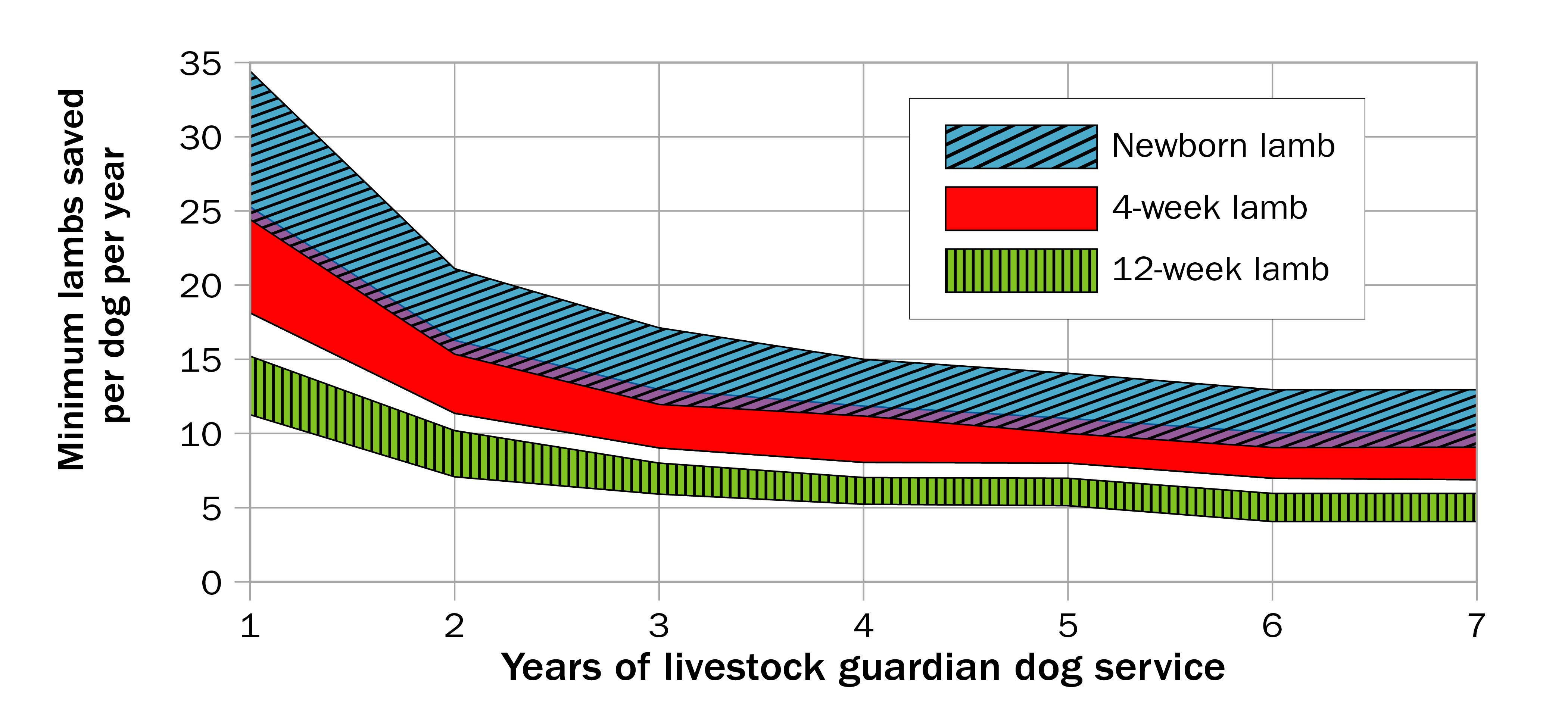

Figure 2 shows the minimum number of lambs that would have to be saved per year to be an economic asset to a sheep operation (for example, value of lambs saved is greater than total costs of LGDs), as a function of the number of years of service of the LGD. This scenario ignores the value of animals saved in the breeding flock, as rates of predation are generally low for mature animals.

The market prices assumed were approximately the range of high ($325/cwt) and low ($225/cwt) peaks of the 5-year (2016–2020) weekly average price of 80–94-lb lambs across all major auction markets in Ontario

Considering the lowest-value lambs, newborn lambs and $225/cwt, a dog providing only 1 year of service (removed from flock at about 2 years) would need to save 34 lambs per year, whereas a dog that provided 5 years of service (removed from flock at about 6 years), would need to save 14 lambs per year. Expenses for the purchase and care of LGDs will vary, so these values may not reflect the number of lambs that need to be saved to be an asset for all operations. It is recommended that an operation calculate these statistics with their own values to understand the cost-effectiveness of LGDs.

Optimum number of LGDs

How many LGDs would be cost-effective for a given flock or herd size? The answer to this question will differ for every operation because it depends on rates of predation, effectiveness of the LGD, as well as prolificacy of the flock.

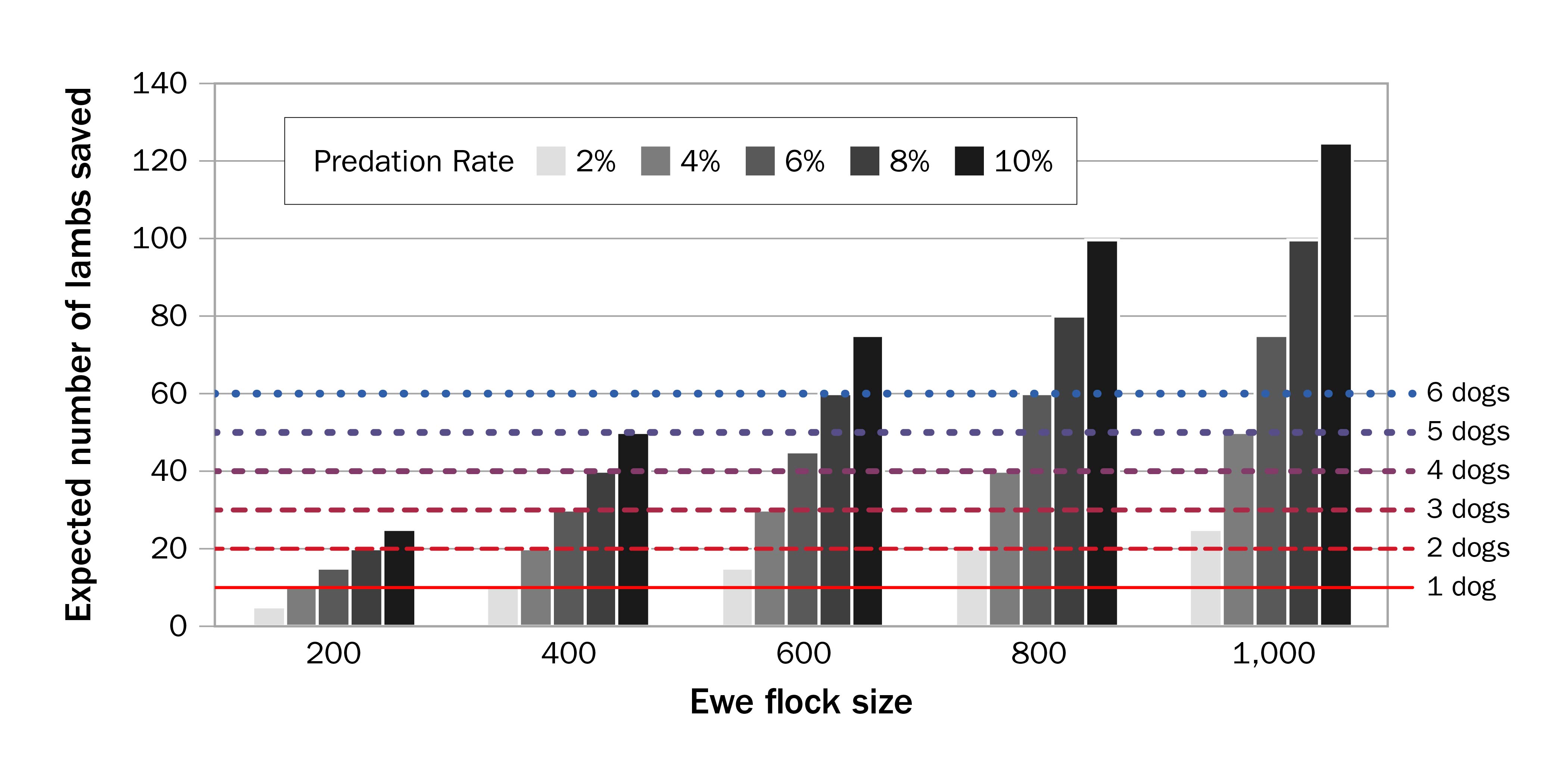

In this scenario, assume that an LGD providing service for 5 years would need to save about 10 lambs of various ages (the mid-point in Figure 2), to be an economic asset.

Under the assumptions for the sample flock presented above, a flock of 200 ewes would produce:

Lamb crop = 200 ewes bred × 90% lambing × 2 lambs per ewe × 99% born alive = 356 lambs

Lambs killed by predation, as a percentage of the total U.S. lamb crop, was estimated to be about 4% in 2014

Based on these assumptions, Figure 3 demonstrates the cost-effectiveness of various numbers of LGDs for flocks from 200–1,000 ewes. The vertical axis shows the number of lambs that would be expected to be saved, given a 70% reduction in the base predation rate, and the horizontal axis shows flock size. The horizontal lines represent the minimum number of lambs saved to be cost-effective for a given number of LGDs. Thus, when interpreting this graph, any bar that exceeds a given line would show a scenario where the number of dogs is expected to be cost-effective for a given flock size and predation rate.

For a flock of 200 ewes, if the predation rate is only 2%, a LGD may not be cost-effective. Whereas 1–2 LGDs may be effective if predation rates are higher than 2%. For a flock of 400, one LGD is cost‑effective at a 2% predation rate, and an additional dog could be effectively added for each 2% increase in predation. For flocks of 600 or more, 1–2 dogs would be expected to be cost-effective for a predation rate of 2% and 3–6+ dogs if predation rates are higher.

These suggested numbers of LGDs are based on the assumptions made, therefore, flocks with lower prolificacy, higher LGD purchase and maintenance costs, or lower effectiveness of dogs would need higher predation rates for a given number of dogs to be cost-effective. Remember that all these calculations ignore indirect economic or non-economic benefits of using LGDs, as previously described. Overall, this figure demonstrates the importance of understanding the flock’s productivity and predation rate to make decisions on the cost‑effectiveness of predation mitigation strategies.

Conclusion

LGDs can be a valuable addition to a predation mitigation strategy for some operations. Research has shown that LGDs can reduce rates of predation by 11%–100%, and most LGD owners believe that their dogs are both effective and an asset to the operation. However, it’s important for producers to have an appropriate number of LGDs for the size of the herd or flock and current rate of predation. Maintaining accurate predation records is critical to understanding predation rates on small ruminant operations and developing a cost-effective predation mitigation strategy.

This fact sheet was written by Erin Massender, small ruminant specialist, Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs.

Footnotes

- footnote[1] Back to paragraph Gehring, T.M., VerCauteren, K.C., and Landry, J-M. (2010). Livestock protection dogs in the 21st century: Is an ancient tool relevant to modern conservation challenges?. USDA National Wildlife Center – Staff Publications. 919, 299-309.

- footnote[2] Back to paragraph United States Department of Agriculture. (2015). Sheep and lamb predator and nonpredator death loss in the United States, 2015. 1–52.

- footnote[3] Back to paragraph O’Brien, A. (2014). Predation management with a focus on coyotes. Alberta Lamb Producers. 1–69.

- footnote[4] Back to paragraph Redden, R.R., Tomeček, J.M., and Walker, J.W. (2015). Livestock guardian dogs. Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service, 1-8.

- footnote[5] Back to paragraph Van Bommel, L., and Johnson, C.N. (2014). Where do livestock guardian dogs go? Movement patterns of free-ranging Maremma Sheepdogs. PloS ONE, 9(10), e111444, 1–12.

- footnote[6] Back to paragraph Green, J.S., and Woodruff, R.A. (1988). Breed comparisons and characteristics of use of livestock guarding dogs. Journal or Range Management, 41(3), 249–251.

- footnote[7] Back to paragraph Van Bommel, L., and Johnson, C.N. (2012). Good dog! Using livestock guardian dogs to protect livestock from predators in Australia’s extensive grazing systems. Wildlife Research, 39, 220–229.

- footnote[8] Back to paragraph Andelt, W.F. (1992). Effectiveness of livestock guardian dogs for reducing predation on domestic sheep. Wildlife Society Bulletin, 20(1), 55–62.

- footnote[9] Back to paragraph Coppinger, R., Coppinger, L., Langeloh, G., Gettler, L., and Lorenz, J. (1988). A decade of use of livestock guarding dogs. Proceedings of the Thirteenth Vertebrate Pest Conference (1988). 43, 209–214.

- footnote[10] Back to paragraph Coppinger, L., and Coppinger, R. (2014). Dogs for herding and guarding livestock. In T. Grandin (Ed.), Livestock Handling and Transport, 4th Ed. (pp. 245-260). CAB International.

- footnote[11] Back to paragraph Saitone, T.I., and Bruno, E.M. (2020). Cost effectiveness of livestock guardian dogs for predator control. Wildlife Society Bulletin, 44(1), 101–109.

- footnote[12] Back to paragraph Smith, M.E., Linnell, J.D.C., Odden, J., and Swenson, J.E. (2000). Review of methods to reduce livestock depredation: I. Guardian animals. Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica, 50, 279–290.

- footnote[13] Back to paragraph Ontario Sheep Farmers. (2021). Weekly market graphs.