American Columbo Recovery Strategy

This document advises the ministry on ways to ensure healthy numbers of the American Columbo, a threatened or endangered species, return to Ontario.

Photo: Nigel Finney

Recovery strategy prepared under the Endangered Species Act, 2007

2013

About the Ontario Recovery Strategy Series

This series presents the collection of recovery strategies that are prepared or adopted as advice to the Province of Ontario on the recommended approach to recover species at risk. The Province ensures the preparation of recovery strategies to meet its commitments to recover species at risk under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) and the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk in Canada.

What is recovery?

Recovery of species at risk is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened, or extirpated species is arrested or reversed, and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of a species’ persistence in the wild.

What is a recovery strategy?

Under the ESA a recovery strategy provides the best available scientific knowledge on what is required to achieve recovery of a species. A recovery strategy outlines the habitat needs and the threats to the survival and recovery of the species. It also makes recommendations on the objectives for protection and recovery, the approaches to achieve those objectives, and the area that should be considered in the development of a habitat regulation. Sections 11 to 15 of the ESA outline the required content and timelines for developing recovery strategies published in this series.

Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for endangered and threatened species within one or two years respectively of the species being added to the Species at Risk in Ontario list. There is a transition period of five years (until June 30, 2013) to develop recovery strategies for those species listed as endangered or threatened in the schedules of the ESA. Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for extirpated species only if reintroduction is considered feasible.

What’s next?

Nine months after the completion of a recovery strategy a government response statement will be published which summarizes the actions that the Government of Ontario intends to take in response to the strategy.

The implementation of recovery strategies depends on the continued cooperation and actions of government agencies, individuals, communities, land users, and conservationists.

For more information

To learn more about species at risk recovery in Ontario, please visit the Ministry of Natural Resources Species at Risk webpage at: www.ontario.ca/speciesatrisk

Recommended citation

Bickerton, H.J. 2013. Recovery Strategy for the American Columbo (Frasera caroliniensis) in Ontario. Ontario Recovery Strategy Series. Prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Peterborough, Ontario. vi + 23 pp.

Cover illustration: Photo by Nigel Finney

© Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2013

ISBN 978-1-4606-3058-7 (PDF)

Content (excluding the cover illustration) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source.

Cette publication hautement spécialisée « Recovery strategies prepared under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 », n’est disponible qu’en anglais en vertu du Règlement 411/97 qui en exempte l’application de la Loi sur les services en français. Pour obtenir de l’aide en français, veuillez communiquer avec Pamela Wesley au ministère des Richesses naturelles au

Authors

Holly J. Bickerton, Consulting Ecologist, Ottawa, Ontario.

Acknowledgments

The following people have provided information and discussion in preparation of this document: Graham Buck, Bill Crins, Ron Gould, Mike Oldham and Eric Snyder (OMNR); Lindsay Campbell (Grand River Conservation Authority); Bill Draper (Ecoplans Ltd.); Nigel Finney (Conservation Halton); Mary Gartshore (St. Williams Nursery and Ecology Centre); Natalie Iwanycki, Dr. Jim Pringle and Ben Stormes (Royal Botanical Gardens); Jarmo Jalava (Carolinian Canada); Mhairi McFarlane (Nature Conservancy of Canada); Carl Rothfels (Duke University); Mirek Sharp (North-South Environmental), and Tyler Smith (Agriculture Canada). Judith Jones (Winter-Spider Eco-consulting) provided thoughtful advice on several aspects of the strategy. Amelia Argue and Leanne Jennings (OMNR) provided critical help in obtaining documents and advice on a number of topics. Nigel Finney provided updated mapping. Many thanks to all.

Declaration

The recovery strategy for the American Columbo was developed in accordance with the requirements of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA). This recovery strategy has been prepared as advice to the Government of Ontario, other responsible jurisdictions and the many different constituencies that may be involved in recovering the species.

The recovery strategy does not necessarily represent the views of all of the individuals who provided advice or contributed to its preparation, or the official positions of the organizations with which the individuals are associated.

The goals, objectives and recovery approaches identified in the strategy are based on the best available knowledge and are subject to revision as new information becomes available. Implementation of this strategy is subject to appropriations, priorities and budgetary constraints of the participating jurisdictions and organizations.

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this strategy.

Responsible jurisdictions

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources

Environment Canada – Canadian Wildlife Service, Ontario

Executive summary

American Columbo (Frasera caroliniensis) is a distinctive perennial herb in the Gentian family (Gentianaceae). The species ranges across central and eastern North America, and although it is considered secure (G5) in North America, it is uncommon throughout its range. In Canada, American Columbo occurs only in southwestern Ontario, and it is listed as endangered under Ontario’s Endangered Species Act, 2007. There are approximately 12 known extant populations, concentrated in areas of Hamilton, Halton, Brant and Niagara. The total population is estimated at 7,633 plants, representing an approximate 80 percent increase since the 2006 COSEWIC status report. However, the apparent increase is likely due to significant search efforts since 2005. A small proportion of the total population of American Columbo occurs within protected areas such as provincial parks and conservation areas. The majority of plants in Canada are found on private land and along utility and transportation corridors.

The life history of American Columbo is unusual. Plants of this species may spend many years as a non-reproductive rosette before flowering, setting seed and dying in the same season. Many plants in a population or region may flower and die in the same year. Flowering is erratic and factors that stimulate it are not known. This reproductive strategy may limit the species’ population and distribution to some degree.

In Ontario, American Columbo grows in upland deciduous habitats, including forests, woodlands and savannas, and also in shrub thickets. It appears to prefer wooded areas with open canopies or canopy gaps but otherwise is tolerant to a wide range of physical and chemical soil conditions. Seeds are probably dispersed mainly by gravity and, to a lesser degree, by water and wind. The main threats to American Columbo in Ontario are habitat loss and fragmentation, invasive plants, utility and transportation corridor management, succession and canopy closure, habitat degradation and erosion.

The recovery goal for American Columbo is to protect all extant populations, to maintain its abundance at each site, and to ensure its long-term persistence within its current Ontario range. Protection and recovery objectives are to:

- protect and manage extant populations and their habitats;

- identify and, where necessary, manage threats to populations and habitats;

- determine population trends and changes to habitat conditions through regular monitoring;

- where feasible and necessary, facilitate recruitment, augment existing populations and consider re-establishing populations at historical sites in suitable habitat; and

- address knowledge gaps related to population status, management, life history, and severity of threats.

It is recommended that the area prescribed as habitat in a regulation for American Columbo include the contiguous Ecological Land Classification (ELC) vegetation type polygon(s) (Lee et al. 1998) within which the species is found. If plants are close to the edge of a vegetation community, a minimum distance of 50 metres from the outer limit of the population is recommended for rgulation. American Columbo occurs in some vegetation communities that are anthropogenic in origin (e.g., shrub thickets), and these may be included in a habitat regulation. Where populations occur in uniform, anthropogenically-maintained habitat along linear utility and transportation corridors, a distance of 50 metres from the outside population limit is recommended for regulation. Mapping of regulated habitat would be beneficial for this species.

1.0 Background information

1.1 Species assessment and classification

- Common name:

- American Columbo

- Scientific name:

- Frasera caroliniensis

- SARO List classification:

- Endangered

- SARO List history:

- Endangered (2008), Special Concern (2004)

- COSEWIC Assessment History:

- Endangered (2006), Special Concern (1993)

- SARA Schedule 1:

- Endangered (200

Conservation status rankings:

- GRANK: G5

- NRANK: N2

- SRANK: S2

The glossary provides definitions for technical terms, including the abbreviations above.

1.2 Species description and biology

Species description

American Columbo (Frasera caroliniensis) is a distinctive member of the Gentian family (Gentianaceae). Each season, plants produce a basal rosette of 3 to 25 oblong, light green leaves that can be up to 40 cm long (COSEWIC 2006). Plants spend most of their lives in this rosette form, persisting for many years before producing a single flowering stem. Flowering stems may grow up to two to three metres in height, with progressively shorter stem leaves growing in whorls, usually of four to five leaves. Flowers are arranged in a large pyramidal inflorescence, with flowering stems emerging from the axils of the upper leaves. Each flower is comprised of four greenish-yellow petals with purplish dots. Petals are fused at the base to form a saucer-shaped flower between two and three centimetres wide (Threadgill et al. 1981a). Seed capsules 1.5 to 2 cm in length typically contain 4 to 14 dark brown, crescent-shaped, winged seeds.

American Columbo is a very striking and robust plant in the Carolinian forest. In flower and fruit, there are no similar species in Canada with which it might easily be confused. Detailed species descriptions and taxonomic keys can be found in Gleason and Cronquist (1991) and Voss and Reznicek (2012). Technical illustrations are shown in Holmgren (1998).

Species biology

The life history of American Columbo is unusual: it is a monocarpic perennial, meaning that plants persist for several years in a non-reproductive form and then die in the season they flower and set seed. Rosettes also wither each season, although the robust flowering stalks may persist for more than a year (COSEWIC 2006).

Following germination and development into a two-leaved seedling, plants form a small rosette in the subsequent season. During this time of pre-reproductive growth, the number of leaves in the rosette increases, and overall size of the plant expands so that the largest plants in a population may have a rosette of up to a metre in diameter (Threadgill et al. 1981a; 1981b). Each July or August, following annual growth, rosettes become dormant. Leaf tissue may wither and decompose by August or September, although flowering stalks may persist. Late-season population estimates for this species are therefore not considered as accurate as those conducted earlier in the season in May and June (Crins and Sharp 1993).

Flowering in Ontario populations usually occurs in June. Factors which stimulate flowering of American Columbo remain poorly understood. The size of the rosette is believed to play a role, although after many years of study, Threadgill et al. (1981a) concluded that size alone is not the determining factor. Flowering in American Columbo is “synchronous”, with many rosettes in a population producing a flowering stalk simultaneously (Threadgill et al. 1981a). Synchronous flowering has been observed during recent fieldwork at several Ontario sites (N. Finney, pers. comm. 2012, N. Iwanycki, pers. comm. 2012). Flowering is also unpredictable: many plants may flower at a site in one year, followed by very few in a subsequent year (Threadgill et al. 1981b). In Ontario, it appears that many, but not all populations will flower in the same year (N. Finney, pers. comm. 2012, N. Iwanycki, pers. comm. 2012). McCoy (1949) suggested that the period of vegetative growth lasts for six to seven years, although this may not be consistent and has not been tested. Threadgill et al. (1979) found that plants can persist for over 30 years in this non-reproductive rosette form.

Horn (1997) observed that flowering plants were more likely to be found in forest openings and along forest margins, and suggested that increased light penetration through the canopy may stimulate flowering. Following flowering and seed set, the plant dies. Unlike long-lived perennials and plants that may reproduce vegetatively, the long-term persistence of American Columbo at a site depends on successful flowering, seed production and seedling establishment. This is due to its monocarpic nature: populations must continually renew themselves through sexual reproduction.

Pollinators are drawn to the many flowers by a large nectar-producing gland situated on each petal. Members of the family Apidae (Order Hymenoptera), including generalist pollinator species such as the European Honeybee (Apis mellifera) and several bumblebee species (Bombus spp.), are the most effective pollinators (Threadgill et al. 1981a). American Columbo is capable of self-pollination, although cross-pollination leads to a higher reproductive output (Threadgill et al. 1981b).

Little is known about seed dispersal. The seeds of American Columbo are presumably dispersed mainly by gravity, and to a lesser extent, water and wind, and are unlikely to spread across large areas of unsuitable habitat (COSEWIC 2006). Dispersal at many sites on steep slopes is most likely to be downslope, into richer areas with less suitable habitat. Most seeds are shed in the late autumn and winter, although viable seeds may remain undispersed on the dead fruiting stalks for more than a year (Baskin and Baskin 1986). Seeds that remain on plants until winter do not germinate the following season, but require an additional season before germinating (Threadgill et al. 1981c, Baskin and Baskin 1986).

Little has been documented about herbivory on American Columbo. Gastropods have been observed feeding on foliage on Ontario populations, but it is not known whether this threatens plant survival (COSEWIC 2006). Threadgill et al. (1981a) found that approximately a quarter of one season’s seed crop at one site was lost to invertebrate predators. Synchronous flowering and seed set in American Columbo may help to reduce seed predation (Threadgill et al. 1981a).

1.3 Distribution, abundance and population trends

Distribution

American Columbo is found throughout a broad area of the central-eastern United States, ranging from Michigan and New York, southward to South Carolina and northern Georgia, and westward to eastern Oklahoma and Louisiana. Although widespread, it is not common anywhere in its range, and is considered of conservation concern (S1-S3, SH) in 9 of 18 American states where it occurs.

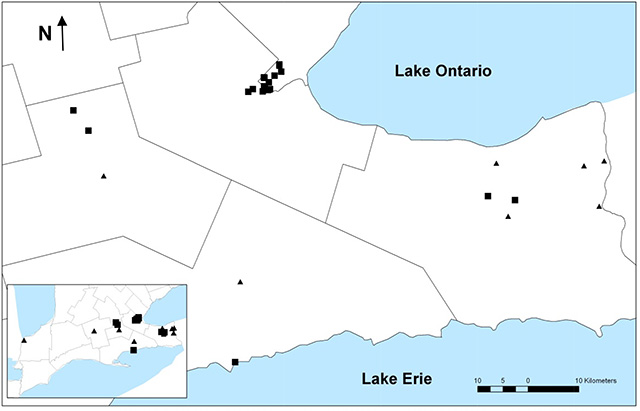

Within Canada, American Columbo is extant only in an area at the western end of Lake Ontario and the eastern end of Lake Erie (Brant County, Regional Municipality of Haldimand-Norfolk, City of Hamilton, Regional Municipality of Halton and Niagara Region; Figure 1). A single disjunct population was documented near Sarnia, Ontario in 1896, and is presumed extirpated.

Abundance and population trends

At the time of the 2006 COSEWIC status report, 22 documented populations (Element Occurrences or EOs) had been reported in Ontario. Of these, 12 were believed to be extant, 9 were considered extirpated populations, and the status of one population was uncertain. The total Canadian (i.e., Ontario) population was estimated at 4,200 plants. Of these, all but a few were in the vegetative state during fieldwork in the seasons of 2004 and 2005 (COSEWIC 2006).

Since that time, fieldwork has been undertaken by staff at Conservation Halton, the Grand River Conservation Authority and the Royal Botanical Gardens. The total Ontario population has recently been estimated at 7,633 (Finney 2012). This apparent 80 percent increase likely reflects a significant and targeted search effort rather than a population increase. Survey effort has been concentrated in Hamilton and Halton regions, where most populations have shown a stable to increasing population (Rothfels 2005, COSEWIC 2006, Finney 2012).

At least three additional populations have been documented; two of these probably represent new Element Occurrences (N. Finney, pers. comm. 2012, N. Iwanycki pers. comm. 2012). Importantly, a significant proportion of plants observed in several Hamilton and Halton populations flowered in 2005, 2009 and again in 2012 (Finney 2012). There have been few recent surveys in the Niagara Region.

Additional populations may also exist but have not been verified. In the Carolinian Woodlands Recovery Strategy (Jalava et al. 2009), American Columbo was identified as a species present at the Aamjinwnang First Nation near Sarnia, Ontario. This report could not be verified. A 2009 observation on private land in the vicinity of Short Hills Provincial Park from the Guelph District Species at Risk database may also represent a new EO; the Short Hills Conservation Action Plan also reports that new populations are being found in this area (Jalava et al. 2010a). No further information is available on these references.

Figure 1. Historical and current distribution of American Columbo in Ontario. Squares represent populations verified since 1993; triangles represent historical populations not observed since 1993. Map courtesy of N. Finney, Conservation Halton.

Enlarge Figure 1. Historical and current distribution of American Columbo in Ontario.

1.4 Habitat needs

Across its range, American Columbo is usually associated with open deciduous forest, although it has been reported from pine and cedar forest in some areas of the United States (Threadgill et al. 1979). Typically, this species occupies stable habitats, but it has been documented from successional shrub thickets as well as recently disturbed habitats. Threadgill et al. (1979) also note that it is most common in dry upland forests, but it has been documented in swampy areas.

In Ontario, most sites are found in deciduous woodlands or forests. These are often dominated by Red Oak (Quercus rubra) or White Oak (Quercus alba), sometimes in association with Hickory (Carya spp.), or less commonly, in Sugar Maple (Acer saccharum) forests, sometimes in association with White Ash (Fraxinus americana) or American Beech (Fagus grandifolia). The canopy is often quite open, or canopy gaps may be present. In Brant County, the species also occurs in oak savanna and tallgrass prairie. These are habitats that are maintained through regular disturbance, which in Ontario, was historically by fire. Some Ontario populations occur, at least in part, under dense shrub thickets dominated by Gray Dogwood (Cornus racemosa), Hawthorns (Crataegus spp.), Buckthorn (Rhamnus spp.), or Staghorn Sumac (Rhus typhina) (Geomatics International 1992). None of the Ontario sites where habitat information has been reported have been located in wetland plant communities.

American Columbo tolerates a range of soil textures and conditions. It has been collected from rocky hillsides, sandy soils, sandy loam and clay; it has been found on calcareous soils and among granite boulders (Threadgill et al. 1979). In Ontario, populations have been reported from dry mesic to mesic clay and clay-loam as well as mesic silty clay.

In Hamilton and Halton, American Columbo has been found in the following Ecological Land Classification (ELC) vegetation types (Lee et al. 1998, Finney 2012):

- Dry-Fresh White Oak Deciduous Forest (FOD1-2)

- Dry-Fresh Oak-Hickory Deciduous Forest (FOD2-2)

- Dry-Fresh Oak-Hardwood Deciduous Forest (FOD2-4)

- Dry-Fresh Sugar Maple-Oak Deciduous Forest (FOD5-3)

- Dry-Fresh Sugar Maple-White Ash Deciduous Forest (FOD 5-8)

- Dry-Fresh White Oak Woodland (WODM3-3)

- Gray Dogwood -Deciduous Shrub Thicket (CUT1-4)

This does not represent a comprehensive list of ELC vegetation communities in which American Columbo is found. No documentation could be found to describe ELC vegetation communities for sites in other areas of Ontario. For example, in Brant County, American Columbo also occurs on private land in oak savanna and tallgrass prairie, although these have not been mapped using ELC methods. In addition, habitat in some areas has been described using methods that preceded the ELC (e.g., Halton Natural Areas Inventory, Varga and Jalava 1992), and some sites still require survey.

1.5 Limiting factors

American Columbo’s reproductive strategy as a monocarpic perennial in a mature forest setting may limit its population to some degree. Individual plants spend many years in a vegetative state. In most years, very few plants flower, and it is quite common to observe no reproductive individuals at a site in a given year (N. Finney, pers. comm. 2012, M. Gartshore, pers. comm. 2012). The fact that American Columbo is not common anywhere in its range suggests that this reproductive strategy, combined with its limited dispersal ability, may limit its population.

1.6 Threats to survival and recovery

Threats are generally presented in order of importance, although the severity of some threats is unclear.

Habitat loss and fragmentation

Habitat loss has historically been a significant threat to this species, with at least 9 of the 22 documented populations presumed extirpated. At least three populations are expected to be affected by development in the future; two of these may be imminently at risk due to planned industrial expansion (COSEWIC 2006, N. Finney, pers. comm. 2012). In Halton and Hamilton, only 17% of Ontario’s American Columbo plants are within publicly owned protected areas (Finney 2012). American Columbo is also restricted to a relatively small and highly developed area of Ontario, where habitat fragmentation is high. Presuming that seeds are dispersed mainly by gravity, the opportunity for wider dispersal of this plant is limited. Habitat fragmentation, and the population isolation that may result, are considered to be threats.

Invasive plants

Fieldwork in advance of the COSEWIC status report (2006) identified that non-native, invasive plants pose a significant threat to this species at its remaining extant sites. This remains the case at many sites (N. Finney, pers. comm., 2012, N. Iwanycki, pers. comm. 2012, L. Campbell, pers. comm. 2012). Non-native, invasive plant species have the potential to outcompete native species for resources and alter habitat such that it becomes unsuitable. Species considered most aggressive at Ontario sites include Dog-strangling Vine (Cynanchum spp.), Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata), Common Buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica), Japanese Barberry (Berberis thunbergii), Multiflora Rose (Rosa multiflora), Tartarian Honeysuckle (Lonicera tatarica), Sweet White Clover (Melilotus alba) and Dame’s Rocket (Hesperis matronalis) (COSEWIC 2006, N. Finney, pers. comm. 2012). The effects of invasive species on germination, reproduction and survival of American Columbo are uncertain. For example, American Columbo continues to persist at sites where Dog-strangling Vine has become dominant in recent years, and the extent to which this affects population viability is not known.

Utility and transportation corridor management

Over 40% of American Columbo plants in Halton and Hamilton occur on lands owned or managed as a utility (hydro) or transportation corridor (Finney 2012). Without careful planning, utility and transportation corridor management has the potential to threaten American Columbo populations through physical impact (cutting, trampling, crushing by heavy equipment), habitat alteration, chemical use, and the possible introduction of invasive species. It is not known whether these impacts are occurring because these activities are currently unmonitored. However, two populations have persisted for at least three decades in thickets along maintained hydro corridors; one of these is among the largest populations in Canada. Herbicides are no longer used by Hydro One; however, in the past, tree species have been removed to encourage dense shrub cover and minimize maintenance requirements (Geomatics International 1991). The effects of these activities on American Columbo are unknown without assessment and monitoring.

Succession and canopy closure

American Columbo is a species of dry forests, woodlands and savannas. There is evidence that this species benefits from open canopies or canopy gaps. Given that natural fire is suppressed in southern Ontario, it is possible that the limited recruitment observed in some populations is a result of canopy closure that results from natural succession. Horn (1997) suggested that American Columbo shows increased flowering at forest margins and in canopy gaps. Recent brush cutting and prescribed burning in American Columbo’s oak savanna habitat in Brant County has resulted in increased recruitment (G. Buck, pers. comm. 2012). Due to a lack of study, it is not clear if canopy closure presents a threat to this species in Ontario (Finney 2012).

Logging

Logging has also been observed as a threat to this species (COSEWIC 2006). The number of populations threatened by logging is not known, but is probably low. Some methods of commercial timber harvest (e.g., clearcutting) would probably threaten American Columbo by causing direct harm to plants, introducing invasive species, or completely altering habitat so that it becomes unsuitable. However, the impact of other types of forestry, such as selective cutting and canopy thinning, may benefit American Columbo populations by creating canopy gaps that stimulate flowering. Such impacts are not known, because no studies have been undertaken to date.

Habitat degradation

Many American Columbo sites are within or near urban areas, and are subject to disturbances that may reduce habitat quality. Dumping of refuse and garden waste has been reported at three sites (COSEWIC 2006), and this could encourage the establishment and spread of invasive plants. Formal and informal trails may result in trampling and/or soil compaction. The suppression of naturally-occurring fire in urban areas, as described above, can also be considered a form of habitat degradation. Thus, although these sites, often on steep slopes, may not be entirely lost, habitat degradation may represent a significant threat.

Erosion

Several Ontario populations of American Columbo occur on steep hillsides, and soil erosion is considered a threat to some sites (COSEWIC 2006, L. Campbell, pers. comm. 2012). However, it is not clear if populations on steeper and more active slopes are necessarily more at risk. Additional study would be beneficial.

1.7 Knowledge gaps

Population and habitat status

Due to recent inventory and monitoring work, there is a wealth of new population information on this species, as well as detailed spatial population mapping. However, the current number of Element Occurrences is not clear, and this species would benefit from a reassessment of the current number and geographic extent of populations and their status. Undocumented reports of this species also exist and require confirmation. Habitat information, threats, and land ownership have been documented at most sites in Halton and Hamilton, but gaps exist for some sites, especially in the Niagara area. Recent census information is lacking for populations in the Niagara Region. The completion of Ecological Land Classification (ELC) to the level of “vegetation type” would inform a habitat regulation for this species.

Management techniques

There is little published information describing the effects of management techniques on American Columbo. Studies examining the effects of vegetation clearing (e.g., brush cutting, forest thinning) and prescribed burning on population persistence and reproduction would provide useful information in managing this population in Ontario. The feasibility of population enhancement and augmentation through propagation and transplanting is not well understood.

Life history, ecological and demographic research

The unusual life history of American Columbo raises many questions regarding the long-term future for this rare species in Ontario. The viability, particularly of small populations, is not known. The factor(s) which trigger synchronous flowering have not been identified to date. Understanding vegetative and reproductive patterns in this species would determine whether seed production and recruitment are sufficient to maintain populations over the long term. Seed dispersal patterns and distances are not known. Information on seed viability in soil and seedling recruitment will also help meet conservation and recovery goals.

Threat clarification

The effects on populations of some proposed threats, particularly of invasive species and soil erosion, are not known. Long-term, experimental invasive species control would help determine the effects of invasive species (and their control) on the long-term viability of American Columbo. Slope stability studies could indicate whether stabilization efforts, where possible, are advisable. A study of seed predation would be useful in determining the reproductive potential of populations (N. Finney, pers. comm. 2012); it is not currently understood whether this constitutes a threat to the species in Ontario (COSEWIC 2006). The extent and effects of soil compaction resulting from formal and informal trail networks is unclear.

1.8 Recovery actions completed or underway

Since 2008, staff at Conservation Halton have conducted inventory work within the City of Hamilton and Halton Region. Information has been collected on total population, reproductive status, and habitat, including ELC communities (Finney 2012). In partnership with the Hamilton Field Naturalists, a long-term monitoring project for the Cartwright Nature Sanctuary population has been initiated. Garlic Mustard control has also been undertaken in the Cartwright Nature Sanctuary (N. Finney, pers. comm. 2012). Sites within the Royal Botanical Gardens (RBG) are monitored frequently, although not on a systematic basis. Staff at the Grand River Conservation Authority (GRCA) have surveyed the Glen Morris population several times between 2007 and 2011 (L. Campbell pers. comm. 2012).

A population at a privately-owned site in Brant County occurs in open oak savanna and woodland, with many prairie species present. With a goal of maintaining oak savanna, brush cutting and three prescribed burns have been conducted between 2007 and 2009. American Columbo has responded positively, with a flush of seedling recruitment in the first years following burning (G. Buck, pers. comm. 2012).

In 1991, a monitoring program was developed for American Columbo populations along two Ontario Hydro rights-of-way (Geomatics International 1991). The program aimed to monitor the species’ status and response to management practices along the rights-of-way. Permanent plots were then established in 1992. Recommendations for future monitoring were given in a subsequent report (Geomatics International 1992). Although this work was discontinued, these two reports provide a useful starting point for further monitoring and research on the effects of management practices on American Columbo abundance, reproductive success, and germination.

Over the past decade, broader scale conservation planning has been underway within this species’ range. A National Recovery Strategy for Carolinian Woodlands and Associated Species at Risk (Jalava et al. 2009) identified recovery approaches for threatened habitats and species, including American Columbo, within the Carolinian life zone. Conservation Action Plans have also been developed for the Short Hills (Jalava et al. 2010a) and Hamilton-Burlington areas (Jalava et al. 2010b). These Conservation Action Plans have been developed collaboratively by a number of community stakeholders to identify and prioritize actions to help recover ecosystems and species-at-risk populations in their target area. Implementation is currently underway (J. Jalava, pers. comm. 2012). A similar, broad-scale, multi-agency approach to land management is being undertaken by the Cootes to Escarpment Park System Project, which incorporates all the American Columbo populations and habitat within Hamilton-Halton (Royal Botanical Gardens 2013, N. Finney, pers. comm. 2012).

2.0 Recovery

2.1 Recovery goal

The recovery goal for American Columbo is to protect all extant populations, to maintain its abundance at each site, and to ensure its long-term persistence within its current Ontario range.

2.2 Protection and recovery objectives

Recovery for this species places greatest emphasis on ensuring the protection of extant populations.

Table 1. Protection and recovery objectives for American Columbo

| No. | Protection or Recovery Objective |

|---|---|

| 1 | Protect and manage extant populations and their habitats. |

| 2 | Identify and, where necessary, manage threats to populations and habitats. |

| 3 | Determine population trends and changes to habitat conditions through regular monitoring. |

| 4 | Where feasible and necessary, facilitate recruitment, augment existing populations and consider re-establishing populations at historical sites in suitable habitat. |

| 5 | Address knowledge gaps related to population status, management, life history, and severity of threats. |

2.3 Approaches to recovery

Table 2. Approaches to recovery of the American Columbo in Ontario

1.0 Protect and manage extant populations and their habitats

| Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Short-term | Inventory and Protection | 1.1 Map the extent of each extant population and its habitat, and identify current landowners and/or land managers. |

|

| Necessary | Short-term | Inventory | 1.2 Investigate references to undocumented and new populations and undertake surveys if necessary to determine if populations are extant. |

|

| Necessary | Short-term | Protection and Communication | 1.3 Contact private landowners and, by working with them, identify opportunities for long-term protection and stewardship (e.g., conservation easements, stewardship agreements, and financial incentives such as Conservation Land Tax Incentive Program or acquisition). |

|

| Necessary | Short-term | Protection and Communication | 1.4 Identify American Columbo habitat under the ESA and work collaboratively with stakeholders, municipalities, conservation authorities, and OMNR to protect habitat. |

|

2.0 Identify and, where necessary, manage threats to populations and habitats

| Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Short-term | Management and Stewardship |

2.1 Prioritize and implement invasive species control at all sites as required.

|

|

| Necessary | Short-term | Management, Communication and Stewardship |

2.2 Manage sites to protect populations.

|

|

| Beneficial | Short-term | Stewardship and Outreach | 2.3 Develop outreach materials for landowners and land managers (e.g., Ontario Hydro, municipalities) to explain the significance and threats to American Columbo, and identify Best Management Practices. |

|

3.0 Determine population trends and changes to habitat conditions through regular monitoring

| Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Short-term | Inventory and Monitoring | 3.1 Comprehensively review all survey and monitoring data to identify and clarify the number of current element occurrences. |

|

| Critical | Short-term | Inventory | 3.2 Compile all population data into a single, current, standard (i.e., Natural Heritage Information Centre) database to ensure that current population information is available to municipalities, conservation authorities, and consultants. |

|

| Necessary | Short-term | Inventory and Monitoring | 3.3 Develop and implement a survey and monitoring protocol for American Columbo. |

|

| Necessary | Long-term | Inventory and Monitoring | 3.4 Conduct population surveys and threat assessments on a regular basis, using a standard protocol. Prioritize surveys of populations in the Niagara region and any others that have not been recently visited. Identify and survey additional sites with apparently suitable habitat within the range of American Columbo. |

|

| Necessary | Long-term | Inventory, Monitoring and Research | 3.5 Develop and implement a standard population monitoring protocol based upon current methods and expertise, to ensure that populations are regularly monitored (every 3–5 years), and results are comparable between years and populations. |

|

4.0 Where feasible and necessary, facilitate recruitment, augment existing populations and consider re-establishing populations at historical sites in suitable habitat

| Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beneficial | Long-term | Management and Restoration | 4.1 Increase the size and (presumably) the viability of extant American Columbo populations by assisting in the spread of seed produced in flowering years, or by other means of augmentation. |

|

| Beneficial | Short-term and Long-term | Management | 4.2 Working with MNR, collect local seed to ensure that local seeds are available for restoration plantings in the short-term. If possible, deposit seed in a reputable seed bank to safeguard the genetics of this species in Ontario. |

|

| Beneficial | Long-term | Restoration | 4.3 Consider habitat restoration and/or re-establishment at historical sites where suitable habitat remains or could be restored. If deemed feasible, develop and implement restoration plans. |

|

| Beneficial | Long-term | Stewardship | 4.4 Integrate management and restoration planning with property management plans (where they exist), as well as larger landscape conservation initiatives (e.g., Conservation Action Plans, the Cootes to Escarpment initiative and other programs of partner agencies) |

|

5.0 Address knowledge gaps related to population status, management, life history, and severity of threats

| Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Necessary | Long-term | Research | 5.1 Conduct detailed demographic studies and population viability analysis, including analysis of seed germination and seedling recruitment rates. |

|

| Necessary | Long-term | Research and Management |

5.2 Conduct research to improve site management.

|

|

| Necessary | Long-term | Research |

5.3 Identify aspects of the life history and ecology of American Columbo that will inform recovery; e.g.:

|

|

| Necessary | Long-term | Research |

5.4 Clarify threats to American Columbo.

|

|

Narrative to support approaches to recovery

The approaches in Table 2 focus on maintaining extant populations, through protection, management, and monitoring. Restoration of habitat and/or populations are lower priority approaches for American Columbo at this time.

Population Viability Analysis is recommended in order to better quantify population goals for recovery. It is currently assumed, although not known, that several larger populations are viable over the long-term. Population Viability Analysis involves detailed demographic analyses of populations (e.g., survivorship, growth and recruitment) over several years in order to estimate the probability of extinction (Menges 1990). Such studies would clarify the extent to which population augmentation and/or re-establishment is required to ensure the long-term persistence of this species in Ontario.

Stewardship and communication strategies are also prioritized. Several landowners have been contacted by Conservation Halton during survey work and are sympathetic to American Columbo conservation; it is recommended that these landowners be identified and contacted to explore stewardship options. Other landowners, including industrial and even municipal landowners, may be unaware of the presence of American Columbo on their properties. Communication and the availability of stewardship incentives (e.g., tax incentives and/or funding for habitat management) will be key to the success of protection of this species on private lands. The co-ordination of stewardship and recovery efforts should be undertaken in the context of regional conservation efforts such as the Carolinian Woodland Recovery Strategy (Jalava et al. 2009), Conservation Action Plans for areas within the range of American Columbo (e.g., Jalava et al. 2010a, Jalava et al. 2010b), and the Cootes to Escarpment Park System landscape planning project (Royal Botanical Gardens 2013).

The availability of current occurrence and survey data to municipalities and consultants through the commonly accepted and standard portal (i.e., Natural Heritage Information Centre database) is critical to the protection of all populations, especially to those recently discovered. Although much survey and monitoring has been completed, the documentation and implementation of standard monitoring methods (especially describing survey timing and the collection of demographic information) would be very valuable.

Based on the available information, the control of invasive species is the most urgent management priority at American Columbo sites. However, careful planning is also required at other populations where habitat is actively managed (e.g., Hydro rights-of-way, managed forests) in order to ensure that American Columbo populations are not harmed.

Re-establishment and re-introduction are considered lower priority recovery approaches at this time, until certain knowledge gaps are filled. Further information about population viability, site maintenance, and the likely success of management techniques will inform the need for such measures in the future.

Many other rare and at-risk Carolinian species occur in American Columbo habitat, including Eastern Flowering Dogwood (Cornus florida, endangered), and several rare Carolinian plants and invertebrates (Finney 2012). Habitat management actions should also consider habitat requirements of other rare and at-risk species within the area.

2.4 Performance measures

Table 3. Performance measures for the recovery of American Columbo

| Objective | Performance measures |

|---|---|

| 1. Protect and manage extant populations and their habitats. |

|

| 2. Identify and, where necessary, manage threats to populations and habitats. |

|

| 3. Monitor all populations regularly, using standard methods, to determine trends and changes to habitat conditions. |

|

| 4. Where feasible and necessary, facilitate recruitment, augment existing populations and consider re-establishing populations at historical sites in suitable habitat. |

|

| 5. Address knowledge gaps related to population status, management, life history, and severity of threats. |

|

2.5 Area for consideration in developing a habitat regulation

Under the ESA, a recovery strategy must include a recommendation to the Minister of Natural Resources on the area that should be considered in developing a habitat regulation. A habitat regulation is a legal instrument that prescribes an area that will be protected as the habitat of the species. The recommendation provided below by the author will be one of many sources considered by the Minister when developing the habitat regulation for this species.

The minimum area that should be prescribed as habitat in a habitat regulation for American Columbo should include the area occupied by all extant populations, and the surrounding extent of the vegetation community in which it occurs. The vegetation community should be described as the vegetation type, based on the ELC methods for southern Ontario (Lee et al. 1998). If plants are close to the edge of a vegetation community, a minimum distance of 50 metres from the outer limit of the population is recommended for regulation. Regulating habitat based on the vegetation community will help to preserve ecological functions required for the recovery of American Columbo, including seed dispersal and recruitment in suitable habitat. Protecting a minimum radius of 50 metres around the extent of each population represents a precautionary approach to ensure the necessary habitat conditions are maintained and that plants are protected from harm.

Recent scientific literature also supports this minimum distance for protection. Effects on both micro-environmental gradients (e.g., light, temperature, litter moisture, etc.) and changes in plant community structure and composition could be detected to 50 metres into habitat fragments (Matlack 1993, Fraver 1994). Roadside effects resulting from construction and traffic typically have the greatest impact within 30 to 50 metres (Forman and Alexander 1998, Forman et al. 2003). Studies that have used mosses or lichens to identify edge effects in forests have also shown effects up to a distance of 50 metres into remnant habitat fragments (Esseen and Renhorn 1998, Baldwin and Bradfield 2005). All of these studies support a minimum 50-metre distance for habitat regulation surrounding each population.

Some of the vegetation types occupied by American Columbo (e.g., Cultural Thicket) may be maintained by human activities (i.e., anthropogenic). These may also be included in a habitat regulation. Clearly unsuitable areas (e.g., paved or manicured areas, and structures) should be exempt from a habitat regulation.

A minority of American Columbo populations (but a large percentage of plants) occurs along linear corridors maintained as hydro rights-of-way or road allowances. In the case of linear corridors where habitat is actively managed, the vegetation type in which American Columbo is found may be contiguous (and maintained as such) over large areas. In these cases, a maximum distance of 50 metres from the outer limit of the population is recommended for protection through regulation. This is to ensure that the necessary habitat conditions are maintained and that plants are protected from harm (see above), as well as to allow natural dispersal of propagules and population expansion.

New information on the species’ habitat management needs should also be considered. There is a significant amount of apparently suitable but unoccupied habitat within the species’ Ontario range, especially considering the extent of its former range. It is therefore recommended that habitat regulation be flexible enough to accommodate newly discovered sites, and those where restoration and/or re-introduction is planned.

American Columbo is not known to be cultivated in Canada, but seeds and rootstocks are commercially available from nurseries in the United States. It is recommended that horticultural populations and those known to have originated from sources outside Canada be excluded from a habitat regulation.

Glossary

- Axil:

- The upper angle where a small stem joins a larger one, or where a leaf stalk joins the stem.

- Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC):

- The committee established under section 14 of the Species at Risk Act that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Canada.

- Committee on the Status of Species at Risk in Ontario (COSSARO):

- The committee established under section 3 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Ontario.

- Conservation status rank:

- A rank assigned to a species or ecological community that primarily conveys the degree of rarity of the species or community at the global (G), national (N) or subnational (S) level. These ranks, termed G-rank, N-rank and S-rank, are not legal designations. The conservation status of a species or ecosystem is designated by a number from 1 to 5, preceded by the letter G, N or S reflecting the appropriate geographic scale of the assessment. The numbers mean the following:

1 = critically imperilled

2 = imperilled

3 = vulnerable

4 = apparently secure

5 = secure

- Cyme:

- An arrangement of flowers in a plant inflorescence in which each axis ends in a flower.

- ELC:

- Ecological Land Classification. This refers to a standard method of vegetation community classification for southern Ontario. For more information, please see Lee et al. (1998).

- Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA):

- The provincial legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Ontario.

- Extant:

- Existing

- Extirpated:

- Locally extinct in a specific region

- Monocarpic:

- A plant that flowers, sets seeds and then dies.

- Population Viability Analysis:

- A method of risk analysis used by conservation biologists to determine the probability that a species will go extinct within a given number of years. The goal is to assess whether the species is self-sustaining over the long term.

- Rosette:

- A plant with leaves spread in a horizontal plane from a short axis (i.e., stem) at ground level.

- Species at Risk Act (SARA):

- The federal legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Canada. This act establishes Schedule 1 as the legal list of wildlife species at risk. Schedules 2 and 3 contain lists of species that at the time the Act came into force needed to be reassessed. After species on Schedule 2 and 3 are reassessed and found to be at risk, they undergo the SARA listing process to be included in Schedule 1.

- Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) List:

- The regulation made under section 7 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that provides the official status classification of species at risk in Ontario. This list was first published in 2004 as a policy and became a regulation in 2008.

- Synchronous flowering:

- Refers to the phenomenon of coincident, simultaneous flowering of a population of a given species, often over a large region. It may involve many plants, but not necessarily all plants of that species.

- Whorl:

- An arrangement in which leaves or petals all arise at the same point on an axis (e.g., stem, branch), encircling it

References

Baldwin, L.K., and G.E. Bradfield. 2005. Bryophyte community differences between edge and interior environments in temperate rain-forest fragments of coastal British Columbia. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 35(3): 580–592.

Baskin, J.M., and C.C. Baskin. 1986. Change in dormancy status of Frasera caroliniensis seeds during overwintering on parent plant. American Journal of Botany 73: 5–10.

Buck, G., pers. comm. 2012. November 2012. Species at Risk Biologist, Guelph District Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources.

Campbell, L., pers. comm. 2012. October 2012. Restoration Specialist, Grand River Conservation Authority, Ontario.

COSEWIC. 2006. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the American Columbo Frasera caroliniensis in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 21 pp.

Crins, B. and M. Sharp. 1993. Status report on the American Columbo Frasera caroliniensis in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 20 pp.

Esseen, P.A., and K.E. Renhorn. 1998. Edge effects on an epiphytic lichen in fragmented forests. Conservation Biology 12(6): 1307–1317.

Finney, N. 2012. Assessment and Status Report on the American Columbo (Frasera caroliniensis) in Halton and Hamilton, Ontario. Unpublished report by Conservation Halton, 13 pp.

Finney, N., pers. comm. 2012. October–November 2012. Watershed Planner, Conservation Halton, Ontario.

Forman, R.T.T., and L.E. Alexander. 1998. Roads and their major ecological effects. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 29: 207–231.

Fraver, S. 1994. Vegetation responses along edge-to-interior gradients in the mixed hardwood forests of the Roanoke River Basin, North Carolina. Conservation Biology 8(3): 822–832.

Forman, R.T.T., D. Sperling, J.A. Bissonette, A.P. Clevenger, C.D. Cutshall, V.H. Dale, L. Fahrig, R. France, C.R. Goldman, K. Heanue, J.A. Jones, F.J. Swanson, T. Turrentine, and T.C. Winter. 2003. Road ecology: Science and solutions. Island Press. Covelo CA. 481 pp.

Gartshore, M., pers. comm. 2012. Ecologist, St. Williams Nursery and Ecology Centre, Ontario.

Geomatics International. 1991. Monitoring program for American Columbo (Frasera caroliniensis): results of first year of monitoring. Unpublished report prepared for Ontario Hydro, December 1991. 12 pp.

Geomatics International. 1992. Monitoring program for American Columbo (Frasera caroliniensis): results of first year of monitoring. Unpublished report prepared for Ontario Hydro, October 1992. 58 pp.

Gleason, H. A. and A. Cronquist. 1991. Manual of Vascular Plants of Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada. The New York Botanical Garden. 910 pp.

Holmgren, N. 1998. The Illustrated Companion to Gleason and Cronquist’s Manual. Illustrations of the Vascular Plants of Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada. The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, New York.

Horn, C.N. 1997. An ecological study of Frixasera caroliniensis in South Carolina. Castanea 62(3): 185-193.

Iwanycki, N., pers. comm. 2012. October 2012. Herbarium Curator and Field Botanist, Royal Botanical Gardens, Burlington, Ontario.

Jalava, J.V., J.D. Ambrose and N. S. May. 2009. National Recovery Strategy for Carolinian Woodlands and Associated Species at Risk: Phase I. Draft 10 – March 31, 2009. Carolinian Canada Coalition and Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, London, Ontario. viii + 75 pp.

Jalava, J.V., J. Baker, K. Beriault, A. Boyko, A. Brant, B. Buck, C. Burant, D. Campbell, W. Cridland, S. Dobbyn, K. Frohlich, L. Goodridge, M. Ihrig, N. Kiers, D. Kirk, D. Lindblad, T. Van Oostrom, D. Pierrynowski, B. Porchuk, P. Robertson, M. L. Tanner, A. Thomson and T. Whelan. 2010a. Short Hills Conservation Action Plan. Short Hills Conservation Action Planning Team and the Carolinian Canada Coalition. x + 74 pp.

Jalava, J.V., S. O’Neal, L. Norminton, B. Axon, K. Barrett, B. Buck, G. Buck, J. Hall, S. Faulkenham, S. MacKay, K. Spence-Diermair and E. Wall. 2010b. Hamilton Burlington 7E-3 Conservation Action Plan. Hamilton – Burlington 7E-3 Conservation Action Planning Team / Carolinian Canada Coalition / Hamilton – Halton Watershed Stewardship Program / ReLeaf Hamilton. v + 79 pp.

Jalava, J., pers. comm. 2012. December 2012. Ecosystem Recovery Co-ordinator, Carolinian Canada.

Lee, H., W. Bakowsky, J. Riley, J. Bowles, M. Puddister, P. Uhlig, & S. McMurray. 1998. Ecological Land Classification for Southern Ontario: First Approximations and Its Application. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. SCSS Field Guide FG-02.

Matlack, G.R. 1993. Microenvironment variation within and among forest edge sites in the eastern United States. Biological Conservation 66(3): 185–194.

McCoy, R,W. 1949. On the embryology of Swertia caroliniensis. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 75: 430–439.

Menges, E. 1990. Population viability analysis for an endangered plant. Conservation Biology 4(1):52–62.

Rothfels, C.J. 2005. American Columbo (Frasera caroliniensis) in the Cartwright nature sanctuary. The Wood Duck 59(1):3–4.

Royal Botanical Gardens. 2013. The Cootes to Escarpment Park System Project. Website: http://archive.rbg.ca/greenbelt/index.html [link no longer active]

Threadgill, P., J.M. Baskin, and C.C. Baskin. 1979. Geographical ecology of Frasera caroliniensis. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 106: 185–188.

Threadgill, P., J.M. Baskin, and C.C. Baskin. 1981a. The floral ecology of Frasera caroliniensis. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 108: 25–33.

Threadgill, P., J.M. Baskin, and C.C. Baskin. 1981b. The ecological life cycle of Frasera caroliniensis, a long-lived monocarpic perennial. The American Midland Naturalist 105: 277–289.

Threadgill, P., J.M. Baskin, and C.C. Baskin. 1981c. Dormancy in seeds of Frasera caroliniensis (Gentianaceae). American Journal of Botany 68: 80–86.

Varga S. and J.V. Jalava. 1992. Biological Inventory and Evaluation of the Sassafras Woods Area of Natural and Scientific Interest, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Southern Region, Aurora, Ontario Open file Ecological Reports 8909. v + 76 pages + 2 folded Maps.

Voss, E.G. and A. A. Reznicek. 2012. Field Manual of Michigan Flora. The University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, Michigan. 990 pp.