Drooping Trillium Recovery Strategy

This document advises the ministry on ways to ensure healthy numbers of the Drooping Trillium, a threatened or endangered species, return to Ontario.

Recovery strategy prepared under the Endangered Species Act, 2007

About the Ontario Recovery Strategy Series

This series presents the collection of recovery strategies that are prepared or adopted as advice to the Province of Ontario on the recommended approach to recover species at risk. The Province ensures the preparation of recovery strategies to meet its commitments to recover species at risk under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) and the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk in Canada.

What is recovery?

Recovery of species at risk is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened, or extirpated species is arrested or reversed, and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of a species' persistence in the wild.

What is a recovery strategy?

Under the ESA, a recovery strategy provides the best available scientific knowledge on what is required to achieve recovery of a species. A recovery strategy outlines the habitat needs and the threats to the survival and recovery of the species. It also makes recommendations on the objectives for protection and recovery, the approaches to achieve those objectives, and the area that should be considered in the development of a habitat regulation. Sections 11 to 15 of the ESA outline the required content and timelines for developing recovery strategies published in this series.

Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for endangered and threatened species within one or two years respectively of the species being added to the Species at Risk in Ontario list. There is a transition period of five years (until June 30, 2013) to develop recovery strategies for those species listed as endangered or threatened in the schedules of the ESA. Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for extirpated species only if reintroduction is considered feasible.

What’s next?

Nine months after the completion of a recovery strategy a government response statement will be published which summarizes the actions that the Government of Ontario intends to take in response to the strategy. The implementation of recovery strategies depends on the continued cooperation and actions of government agencies, individuals, communities, land users, and conservationists.

For more information

To learn more about species at risk recovery in Ontario, please visit the Ministry of Natural Resources Species at Risk webpage at: www.ontario.ca/speciesatrisk

Recommended citation

Jalava, J.V. and J.D. Ambrose. 2012. Recovery Strategy for the Drooping Trillium (Trillium flexipes) in Ontario. Ontario Recovery Strategy Series. Prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Peterborough, Ontario. vi + 20 pp.

© Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2012

ISBN 978-1-4435-9427-1

Content (excluding the cover illustration) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source.

Cette publication hautement spécialisée Recovery strategies prepared under the Endangered Species Act, 2007, n'est disponible qu'en Anglais en vertu du Règlement 411/97 qui en exempte l'application de la Loi sur les services en français. Pour obtenir de l'aide en français, veuillez communiquer avec Pamela Wesley au ministère des Richesses naturelles au 1-705-755-5217.

Authors

Jarmo Jalava – Consulting Ecologist, Carolinian Canada Coalition

John D. Ambrose – Carolinian Woodlands Recovery Team

Acknowledgments

Earlier drafts of this recovery strategy were prepared in consultation with the Carolinian Woodlands Plants Technical Committee, consisting of Dawn Bazely (York University), Jane Bowles (University of Western Ontario), Barb Boysen (Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, OMNR), Dawn Burke (OMNR), Peter Carson (Private consultant), Ken Elliott (OMNR), Mary Gartshore (Private consultant), Karen Hartley (OMNR), Steve Hounsell (Ontario Power Generation), Donald Kirk (OMNR), Daniel Kraus (Nature Conservancy of Canada), Nikki May (Carolinian Canada), Gordon Nelson (Carolinian Canada), Michael Peppard, Bernie Solymar (Private consultant), Tara Tchir (Upper Thames Conservation Authority), Kara Vlasman (OMNR) and Allen Woodliffe (OMNR). Kate Hayes (Environment Canada / Savanta), Karen Hartley (OMNR), Chris Risley (OMNR) and Muriel Andreae (St. Clair Region Conservation Authority) were particularly helpful in providing information and advice during the preparation of this strategy in its early stages, and Michael Oldham (OMNR), Ron Gould (OMNR), Judith Jones (Winter Spider Eco-consulting) were especially helpful in the latter stages. Manon Dubé, Angela Darwin, Graham Bryan and Christina Rohe of the Canadian Wildlife Service, and Eric Snyder, Bree Walpole and Wasyl Bakowsky of the OMNR, reviewed a late draft. Allen Woodliffe (OMNR) provided essential information and guidance throughout the development of the strategy.

Declaration

The recovery strategy for the Drooping Trillium has been prepared in accordance with the requirements of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA). This recovery strategy represents advice to the Government of Ontario, other responsible jurisdictions and the many different constituencies that may be involved in recovering the species.

The recovery strategy does not necessarily represent the views of all of the individuals who provided advice or contributed to its preparation, or the official positions of the organizations with which the individuals are associated.

The goals, objectives and recovery approaches identified in the strategy are based on the best available knowledge and are subject to revision as new information becomes available. Implementation of this strategy is subject to appropriations, priorities and budgetary constraints of the participating jurisdictions and organizations.

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this strategy.

Responsible jurisdictions

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources

Environment Canada – Canadian Wildlife Service, Ontario

Executive summary

Drooping Trillium (Trillium flexipes) is a perennial herb in the lily family, with the core of its range in the eastern United States. There are only two known extant occurrences of Drooping Trillium in Canada, both in extreme southwestern Ontario. Five historic occurrences were extirpated between 1848 and 1950. Drooping Trillium was designated as endangered by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife In Canada (COSEWIC) in 1996 (reassessed in 2000 and 2009) and by the Committee on the Status of Species At Risk in Ontario (COSSARO) in 2008. These designations are due to a highly reduced number of occurrences which are limited by low seed set and lack of habitat for population expansion and which also are threatened by human activities. The species is listed as endangered under Ontario’s Endangered Species Act, 2007 and the federal Endangered Species Act, 2007.

Drooping Trillium grows in rich beech-maple, oak-hickory or mixed deciduous swamps and floodplain forests which are usually associated with watercourses. The presence of a watercourse may benefit the plant by creating and maintaining a slightly elevated floodplain terrace where soils are a well-drained combination of loam and sand favourable to the species. Forest canopy cover is important to maintain woodland ground flora and to reduce competition with invaders of forest openings, although some light penetration appears to increase plant vigour and population densities of this species.

The main threats to the Canadian populations of Drooping Trillium are considered to be habitat loss or degradation associated with incompatible forestry practices, recreational trail use, invasive species and alterations to soil hydrology. The potential threats of collecting for horticultural uses, diseases, pests, and herbivory by deer have also been noted.

The recovery goal is to establish and maintain a viable population of Drooping Trillium in its current and historic range in Ontario. This will involve population viability analyses to determine if, and the degree to which, extant populations need to be enhanced. Such analyses also will determine the number and size of additional populations that need to be established in the species' historical range in southern Ontario. The objectives to achieve this goal are to:

- protect and manage habitat to establish and maintain a viable population of Drooping Trillium in Ontario;

- determine abundance, extent, health and dynamics of Drooping Trillium populations in Ontario through inventory and regular monitoring;

- address key knowledge gaps relating to the species' biology, ecology, habitat and threats;

- promote awareness and stewardship of Drooping Trillium with land managers, private landowners, municipalities, horticultural organizations and other key stakeholders; and

- where it is ecologically and logistically feasible, reintroduce Drooping Trillium to historical or other ecologically suitable sites.

Due to the isolated nature of the extant populations, a strategic management and stewardship approach is recommended. This includes coordination and consultation with a variety of partners including private landowners and the St. Clair Region Conservation Authority.

Given that Drooping Trillium does not occupy all apparently suitable habitat at the extant sites, it is suggested that the area occupied by the plants, as well as adjacent habitat extensive enough to protect the hydrological regime allowing for potential dispersal and population expansion be prescribed as habitat in the regulation. It is recommended that the area prescribed as habitat in a regulation for Drooping Trillium be a composite area delineated by applying the following two criteria: (1) a distance of 120 m from the outer limits of the area occupied by Drooping Trillium in order to protect the hydrological regime, and (2) the full extent of the Ecological Land Classification (ELC) ecosite polygon within which a population occurs. As new information on the species' habitat requirements and site-specific characteristics (such as hydrology) become available, these attributes should be used to refine the habitat definition. It is also recommended that the habitat regulation for Drooping Trillium be flexible enough to include repatriation and/or introduction sites that are necessary or beneficial to recovery. Drooping Trillium is occasionally cultivated for horticulture. Horticultural populations should be excluded from the regulation.

1.0 background information

1.1 Species assessment and classification

Common name: drooping trillium

Scientific name: Trillium flexipes

SARO List Classification: Endangered

SARO List History: Endangered (2008), Endangered – Regulated (2004)

COSEWIC Assessment History: Endangered (2009, 2000, 1996)

SARA Schedule 1: Endangered

Conservation status rankings:

GRANK: G5

NRANK: N1

SRANK: S1

The glossary provides definitions for technical terms, including the abbreviations above.

1.2 Species description and biology

Species description

Drooping Trillium (Trillium flexipes), also known as "Bent" or "Nodding" Trillium is a herbaceous perennial with a sturdy, upright stem that stands 15 to 60 cm tall. Its three leaves found at the top of the stem in a whorl are broad, sessile and abruptly pointed and are up to 20 cm long. A single flowering stalk, emerging from the junction of three leaves, sharply curves and grows 3 to 12 cm downward. The majority of plants have their flowers below the level of the leaves. In some plants, the flower stalk can be horizontal or (very rarely) erect. The flower consists of three obtuse petals (each two to five centimetres long) and often has a stale or musty fragrance. The flower is normally white but can be reddish or maroon. Plants with coloured petals are probably hybrids.

Unlike Drooping Trillium which has very short filaments, Nodding Trillium (T. cernuum) and Red Trillium (T. erectum), two similar species found in southern Ontario, both have filaments almost as long as the anthers. Other distinguishing features of these species are provided in COSEWIC (2009).

Species biology

Drooping Trillium is a spring ephemeral that takes an average of ten years to reach a reproductive flowering state. It blooms from April to June and reproduces sexually. Although the flowers are usually self-pollinated, the long stamen and drooping peduncle suggest that some bumblebees and butterflies could be potential cross-pollinators. Vegetative reproduction through rhizomes has also been observed, but this mode of reproduction is not common (Ransom-Hodges 2006). Seeds are the primary source of new plants. Ants are effective short range dispersal agents (McLeod 1996). In Canada, both extant occurrences are thought to be reproducing successfully since both contain many young (non-flowering) plants.

Hybridization between Drooping Trillium and Red Trillium (T. erectum) is possible (Ransom-Hodges 2006). It has been shown that the red forms of Drooping Trillium are likely to be hybrids since they occur in places where the ranges of both species coincide (McLeod 1996). Hybridization is also suspected between Drooping Trillium and another related species that occurs only in the United States - Barksdale Trillium (T. sulcatum) - with morphological intermediates being produced (Patrick 1984).

Two seasons of cold are required for germination of seeds, known as double dormancy (Ransom-Hodges 2006). Drooping Trillium does not occur in high densities, with densities of 0.02 plants per square metre and 0.075 plants per square metre at the two extant locations in Ontario (Ransom-Hodges 2006). Associations between Drooping Trillium and mycorrhizal fungi have been observed (DeMars and Boerner 1995).

1.3 Distribution, abundance and population trends

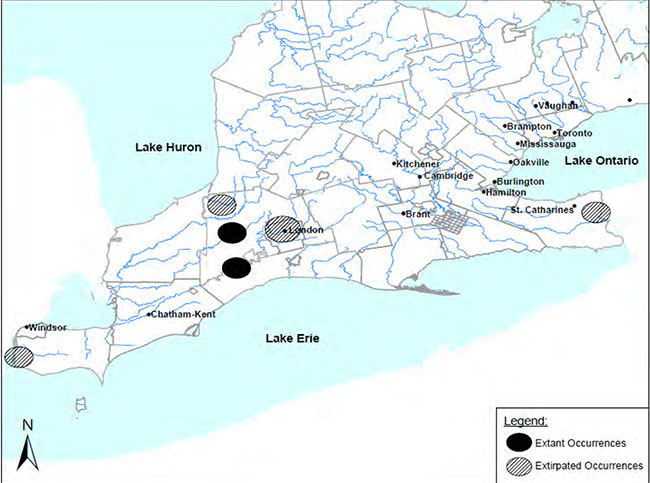

Drooping Trillium is found in central United States and adjacent southwestern Ontario, from western New York to southeastern Minnesota, south to northeastern Alabama, with disjunct populations in northern Arkansas, western North Carolina, southeastern Pennsylvania, adjacent Delaware and Maryland (Figure 1). The global rank for Drooping Trillium is G5, or secure. It is ranked S1, S2 or historic in ten states, S3 in two and not ranked in ten (NatureServe 2011). The percentage of global range in Canada is likely less than one percent. It is ranked as N1 or critically imperilled in Canada and as S1 or critically imperilled, in Ontario.

The Canadian range of Drooping Trillium is limited to extreme southwestern Ontario and includes two extant occurrences

The extant occurrence on St. Clair Region Conservation Authority land and two adjoining private properties (one of them a golf course, the other undeveloped) along the Sydenham River in Middlesex County had 1,012 flowering and 105 vegetative stems in 2007 covering an area of 7.1 ha (Harris and Foster 2008). The Dunwich occurrence in Elgin County is in the forested valley of the Thames River on a private agricultural property where 453 flowering stems were counted by Harris and Foster (2008) in an area covering 0.9 ha. Another 14 non-flowering plants (97% flowering) were also found. However the surveyors felt that additional plants were probably present but not found due to the density of other herbaceous cover at the site.

The recent counts at the Sydenham River and Thames River sites suggest apparent increases in population size at both when compared to McLeod (1996). According to Harris and Foster (2008), since 1994 the number of flowering plants has apparently more than doubled at the Sydenham site and increased by a factor of six at the Thames site. There was also an apparent increase in area of occupancy at both sites.

However, it is possible that the disparity in totals reflects differences in survey methods and extent rather than actual population growth. According to Woodliffe (pers. comm. 2009), regular monitoring of the Sydenham population has found that population numbers are quite variable from year to year, probably due to annual climatic variations.

Figure 1. Historical and current distribution of Drooping Trillium in Ontario (based on NHIC data, 2011)

Enlarge historical and current distribution of Drooping Trillium in Ontario map

1.4 Habitat needs

Drooping Trillium grows in rich beech-maple, oak-hickory or mixed deciduous swamps and floodplain forests which are usually associated with watercourses. The presence of a watercourse may benefit the plant by creating and maintaining a slightly elevated floodplain terrace where the soils are a combination of well-drained loam and sand favourable to the species. The species appears to prefer circumneutral soil types (COSEWIC 2009) occurring over calcareous bedrock (Case 2002, Gleason and Cronquist 1991).

A study of forest-floor herbaceous plants along the Susquehanna River riparian corridor in northeastern Maryland and southeastern Pennsylvania found Drooping Trillium to show a strong fidelity to the larger tracts of mature riparian forest with rich mesic soils, with the species seldom being found in smaller forest patches and stands on drier, poorer soils (Bratton et al. 1994). Forest canopy cover is important to maintain woodland ground flora and to reduce competition with aggressive light-tolerant plant species which include a number of introduced and invasive taxa.

At the two extant Ontario occurrences, relatively high population densities and greater plant vigour have been observed along a walking trail and in a selectively logged forest (McLeod 1996, Harris and Foster 2008, NHIC 2011). This suggests that light selective logging has not seriously impacted the habitat of the species and that low levels of pedestrian trail use (to a certain threshold) may in fact benefit the species by maintaining a slightly open canopy. Minimum canopy cover of 75% should be retained however. An optimum level of disturbance may be a requirement of the species.

COSEWIC (2009) and Harris and Foster (2008) provide detailed habitat descriptions for the two extant occurrences in Ontario:

At the Sydenham River occurrence, overstorey vegetation consists mainly of White Ash (Fraxinus americana), Silver Maple (Acer saccharinum), Sugar Maple (A. saccharum), Manitoba Maple (A. negundo) and Basswood (Tilia americana). Most plants are on the floodplain of the Sydenham River but occur mainly on slightly-raised, drier microhabitats than the surrounding Skunk Cabbage (Symplocarpus foetidus). A few plants occur on the banks of the ravine. The shrub layer varies from open with only a few scattered shrubs and saplings, to areas where more densely concentrated patches occur. Common woody species include Gray Dogwood (Cornus racemosa), Witch-hazel (Hamamelis virginiana), Chokecherry (Prunus virginiana) and introduced honeysuckles (Lonicera spp.). The main herbaceous species associated with Drooping Trillium at this site are Ostrich Fern (Matteuccia struthiopteris), Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata), Wild Ginger Asarum canadense) and Jack-in-the-Pulpit (Arisaema triphyllum).

At the Thames River site most plants occur on upper terraces above the floodplain. Overstorey vegetation is mainly American Beech (Fagus americanus), Hackberry (Celtis occidentalis), Black Maple (Acer nigrum), American Elm (Ulmus americana), Slippery Elm (U. rubra), White Ash and Blue Ash (Fraxinus quadrangulata). Most of the habitat was subjected to selective logging in about 2003 when most trees greater than about 25 cm diameter at breast height (1.3 m) were cut. The resultant stand has a fairly open canopy with dense regeneration of False Solomon’s-seal (Maianthemum racemosum). The most common ground cover associates were White Baneberry (Actaea pachypoda), Trout Lily (Erythronium canadensis), Jack-in-the-Pulpit, Spotted Jewelweed (Impatiens capensis), False Solomon’s-seal, May-apple (Podophyllum peltatum), Bluestem Goldenrod (Solidago caesia) and Garlic Mustard. The site was apparently also logged prior to 1970 (McLeod 1996).

1.5 Limiting factors

Drooping Trillium is at the northern limit of its range in Ontario and climate likely restricts its ability to expand its populations.

One study found that each Drooping Trillium flower produces more ovules on average than seven other pedicellate-flower species studied in North America. However its seed production was the second lowest among them, indicating a low fertilization rate due to inefficient self- and/or cross-pollination mechanisms (Ransom-Hodges 2006).

Population expansion of Drooping Trillium in Ontario may therefore be limited by low seed production rates combined with the species' restricted dispersal ability and pollinating agents.

Drooping Trillium’s requirement for closed-canopy forest and the current fragmented configuration of such habitat within its Canadian range also undoubtedly affects its ability to disperse and colonize otherwise suitable sites. Bratton et al. (1994) note that Drooping Trillium may have difficulty reestablishing populations in fragmented woodlots once they have been extirpated.

Other limiting factors may include a dependence on mycorrhizal fungi and soil moisture levels which may to some extent be interrelated (DeMars and Boerner 1995).

1.6 Threats to survival and recovery

Urban and agricultural development

The greatest historic threat to Drooping Trillium in Ontario has been from habitat loss and degradation. A study of forest-floor herbaceous plants along the Susquehanna River riparian corridor in northeastern Maryland and southeastern Pennsylvania found Drooping Trillium to be one of the most sensitive herbaceous understory plants to forest fragmentation seldom found in small forest patches (Bratton et al. 1994). An historic occurrence at London probably succumbed to habitat loss as a result of urban development. Occurrences along the Detroit River in Essex County, last reported 150 years ago, probably met the same fate as the area is now quite densely populated.

Incompatible forestry practices

Bratton et al. (1994) found that Drooping Trillium rarely occurred in younger successional stands that had undergone heavy selective logging. Habitat modification at the Thames River site may have been produced by pre-1970 selective timber harvesting (McLeod 1996). Another selective cut occurred in the early 2000s (Harris and Foster 2008). Excessive exposure to solar radiation along with direct damage to the plants by logging equipment may have been detrimental to this population but the actual impacts cannot be assessed because of the absence of historical data for this site (McLeod 1996).

Trails and recreational activities

At the Sydenham River occurrence, habitat degradation has occurred with the construction of trails and the use of off-road vehicles in Drooping Trillium habitat. According to COSEWIC (2009), a trail passes directly through the Drooping Trillium population at the publicly-owned conservation area. Inadvertent damage to trail-side plants has occurred, both from trampling by hikers and from the unauthorized use of all- terrain vehicles (ATVs), which are too wide for the trail and leave a continuous swath of crushed vegetation in their wake along one and sometimes both sides of the trail. The anticipated population growth in the area likely will result in a greater recreational demand. This will increase the pressure on the Drooping Trillium population unless mitigating measures are taken.

Exotic or invasive species

Increased competition for ecological resources from alien plant species such as Garlic Mustard has been cited in COSEWIC (2009) as potentially posing a threat to the two extant Drooping Trillium occurrences. At the Sydenham River occurrence, Garlic Mustard and non-native honeysuckles (Lonicera spp.) are abundant in the Drooping Trillium habitat. At the Thames River site several invasive species, including Garlic Mustard, are also present but are less abundant (Harris and Foster 2008).

Exotic earthworms also pose a threat to plants of deciduous forests of eastern North America. In a recent study, earthworm invasion resulted in significant changes to the location and nature of nutrient cycling activity in the soil profile (Bohlen et al. 2004). The impacts of earthworms included: altered soil total carbon and phosphorus pools; changes to carbon: nitrogen ratios; and modifications in the distribution and function of roots and microbes (Bohlen et al. 2004.). Implications of such changes on forest understorey species are not well understood currently, but the impacts may be serious.

Alterations to hydrology

Given that Drooping Trillium is strongly associated with riparian forests in Ontario, changes to soil hydrology resulting from land uses higher in the watershed (such as from dam construction, channelization, ditching, water-taking, tile drainage) may also be a significant threat affecting habitat quality and suitability.

Consumptive use

The growing native wildflower gardening industry and the particular popularity of trillium species may pose a future threat to both of Ontario’s extant occurrences because of the demand by local gardeners for mature plants. Although removal of plants from conservation areas is strictly prohibited, the Sydenham River site is likely to be at greater risk in this respect because of its proximity to an urban population and the ease of access to this site (COSEWIC 2009).

Diseases and pests

Potential diseases associated with a fungus (Botrytis) and a mycoplasma bacterium and infestation by a species of Clepsis moth have not been observed in Ontario populations of Drooping Trillium. However, these potential threats, especially if combined with herbivory by White-tailed Deer (Augustine and Frelich 1998) before maturation of seed, could present a threat if effects were widespread and occurred for several successive years in the same population.

Hyperabundant predator populations

White-tailed Deer were noted in 2007 as having browsed many of the Drooping Trilliums at the Sydenham River occurrence (Harris and Foster 2008). The relatively low population size and small area occupied by the Thames River population may render it particularly vulnerable to destruction by potential disease, insect infestations and White- tailed Deer herbivory. (COSEWIC 2009)

Dumping of litter

An additional threat to habitat at the Thames River site is dumping of trash (e.g., bales of fence wire) (Harris and Foster 2008).

1.7 Knowledge gaps

Addressing the following knowledge gaps will contribute to the successful recovery of the Drooping Trillium in Canada:

- better definition of its specific habitat requirements, including: (a) clarification of the effects of water quality and changes in the hydrologic regime on habitat dynamics; (b) soil preferences; and (c) optimum levels of canopy closure and solar radiation;

- better information on: (a) current status of populations and habitat condition at historical sites; (b) degree of annual fluctuation in population size and flowering numbers at extant occurrences; and (c) whether additional areas of suitable habitat support the species in Ontario;

footnote 3 - better understanding and prioritization of threats to the species;

- better understanding of the biology of the species (i.e., seed productivity, fertility, pollination and long range dispersal mechanisms);

- knowledge of the degree to which Drooping Trillium hybridizes with other trillium species in Ontario;

- an understanding of minimum viable population levels; And,

- understanding the establishment requirements before introduction into historic sites or new habitats is considered.

1.8 Recovery actions completed or underway

A number of projects to improve water quality has been undertaken upstream of the Sydenham River site under the Sydenham River Aquatic Ecosystem Recovery Strategy. Also, the St. Clair Region Conservation Authority established formal trails through the conservation area. Chips and dust were spread on some of the trails and this may have resulted in some negative effects on trilliums located immediately adjacent to the trails. However, the more formal delineation of the trail encourages people to stay on the path and also discourages the creation of new informal paths.

A comprehensive inventory and evaluation of the status of the two extant Ontario occurrences was undertaken in 2007 as part of the COSEWIC (2009) update status report on the species (Harris and Foster 2008).

Carolinian Canada Coalition developed a draft Best Management Practices (BMP) fact sheet for Drooping Trillium in early 2011 with the support of the Ontario Species at Risk Stewardship Fund. Carolinian Canada Coalition is also preparing broader habitat- based BMP "menus."

2.0 Recovery

2.1 Recovery goal

The recovery goal is to establish and maintain a viable population of Drooping Trillium in its current and historic range in Ontario. This will involve population viability analyses to determine if, and the degree to which, extant populations need to be enhanced as well as the number and size of additional populations that need to be established in the species' historical range in southern Ontario.

2.2 Protection and recovery objectives

Table 1. Protection and recovery objectives

| No. | Protection or recovery objective |

|---|---|

| 1 | Protect and manage habitat to establish and maintain a viable population of Drooping Trillium in Ontario. |

| 2 | Determine abundance, extent, health and dynamics of Drooping Trillium populations in Ontario through inventory and regular monitoring. |

| 3 | Address key knowledge gaps relating to the species' biology, ecology, habitat and threats. |

| 4 | Promote awareness and stewardship of Drooping Trillium with land managers, private landowners, municipalities, horticultural organizations and other key stakeholders. |

| 5 | Where it is ecologically and logistically feasible, reintroduce Drooping Trillium to historical or other ecologically suitable sites. |

2.3 Approaches to recovery

Table 2. Approaches to recovery of the Drooping Trillium in Ontario

-

Protect and manage habitat to establish and maintain a viable population of Drooping Trillium in Ontario

| Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Short-term | Protection, Management | 1.1 Develop Best Management Practices (BMPs) to include guidelines for appropriate forest, watershed and trail management as well as a species-specific BMP for Drooping Trillium. |

|

| Critical | Short-term | Protection, Management | 1.2 Provide recommendations and BMPs to landowners and land managers. |

|

| Beneficial | Long-term | Protection | 1.3 Identify key sites to secure in the context of the overall Carolinian Woodlands Recovery Strategy. |

|

| Beneficial | Long-term | Protection | 1.4 Secure key sites through easements or purchase. |

|

-

Determine abundance, extent, health and dynamics of Drooping Trillium populations in Ontario through inventory and regular monitoring

| Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Short-term | Inventory, Monitoring and Assessment | 2.1 Inventory sites of historic reports. |

|

| Critical | Short-term | Inventory, Monitoring and Assessment | 2.2 Identify and survey additional sites with suitable habitat. |

|

| Beneficial | Short-term | Inventory, Monitoring and Assessment | 2.3 Review herbarium specimens of Drooping Trillium and similar species to ensure that all have been identified correctly. |

|

| Necessary | Short-term | Inventory, Monitoring and Assessment | 2.4. Develop monitoring strategy for Drooping Trillium. |

|

| Necessary | Ongoing | Inventory, Monitoring and Assessment | 2.5. Apply monitoring strategy (where appropriate, in association with monitoring of other priority species at risk). |

|

-

Address key knowledge gaps relating to the species' biology, ecology, habitat and threats

| Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Short-term | Research | 3.1 Assess threats based on field inspections at extant and key historic sites. |

|

| Critical | Short-term | Research | 3.2 Conduct hydrological study at extant sites to better understand habitat processes and needs. |

|

| Critical | Short-term | Research | 3.3 Identify the positive and/or negative impacts of land-use and management practices. |

|

| Critical | Short-term | Research | 3.4 Conduct population viability analysis. |

|

| Necessary | Long-term | Research |

3.5 Engage academic community to:

|

|

| Beneficial | Long-term | Research | 3.6 Research seed productivity and fertility in Ontario. |

|

-

Promote awareness and stewardship of Drooping Trillium with land managers, private landowners, municipalities, horticultural organizations and other key stakeholders

| Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Necessary | Short-term | Education and Outreach | 4.1. Develop outreach materials that highlight the significance, vulnerability and threats to Drooping Trillium, emphasizing the threat of illegal collecting. |

|

| Necessary | Short-term | Education and Outreach, Communication | 4.2. Disseminate these materials to target audiences (horticultural clubs, landscaping companies, plant nurseries) and the general public. |

|

-

Where it is ecologically and logistically feasible, reintroduce Drooping Trillium to historical or other ecologically suitable sites

| Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beneficial | Long-term | Stewardship | 5.1. Based on assessments of threats, studies of the species' biology and ecology, population viability analysis, determine the feasibility and necessity of reintroduction. |

|

| Beneficial | Long-term | Stewardship | 6.1 Reintroduce species to historical or other suitable sites, if deemed feasible. |

|

Narrative to support approaches to recovery

The specific approaches and studies outlined in Table 2 are needed to reduce the immediate jeopardy of Drooping Trillium. The two historical sites in Middlesex should be surveyed to ascertain whether the species is extant or has been extirpated. Better understanding of minimum viable population size, demographic structure, the essential features and the processes required to maintain suitable habitat are recommended. As well, ongoing assessments of habitat condition and threats are recommended at both extant and key historic sites in order to prioritize recovery activities.

Many of the recovery steps recommended in this strategy should be accomplished in coordination with steps being planned for other Carolinian woodland species at risk in existing and developing parallel strategies. The needs of Drooping Trillium should be incorporated into Best Management Practices (BMPs) for woodlands, municipal natural heritage systems mapping and protection legislation, activities of conservation authorities and stewardship council projects. Recovery actions should be coordinated with efforts being undertaken by the Sydenham River Aquatic Ecosystem Recovery Team (Dextrase et al. 2003), the Thames River Species at Risk Recovery Team (TRRT 2007) and the St. Clair Region Conservation Authority.

Approaches to recovery for Drooping Trillium will be incorporated into the implementation strategies of the Carolinian Woodland Recovery Strategy (Jalava et al. 2008, Jalava and Mansur 2008) and associated action plans. The focus of the Carolinian Woodland Recovery Strategy is to improve the integrity of those portions of the Carolinian woodland landscape in which species at risk occur. This initiative will be undertaken in concert with other broader ecosystem-based strategies such as the Sydenham River (Dextrase et al. 2003) and Thames River (TRRT 2007) recovery strategies, Conservation Action Planning for Carolinian ecosystem recovery, Ontario’s Biodiversity Strategy, and the Nature Conservancy of Canada’s Conservation Blueprint and Natural Area Conservation Plans.

2.4 Performance measures

Measures of the success of the recovery effort will form part of the regular monitoring program. Measures will include long term trends in the size and number of extant sites (area of occupancy and area of extent), site quality (measured through a habitat suitability index) and population trends and projections determined through regular population counts. A scoring system should be developed to allow for quantitative comparisons between Drooping Trillium populations and factors affecting the quality and extent of its woodland habitat.

Monitoring may be undertaken at varying levels of intensity in the future depending on the current threat level, size and quality of each site (Bickerton 2003) as follows.

- At a minimum, a less-intensive level of monitoring may be undertaken by volunteers or landowners annually or biannually at sites considered to be less critical from the point of view of threats, size and quality. Performance measures would include the presence or absence of Drooping Trillium and an approximate population count, a coarse numerical assessment of threats and qualitative assessment of changes to habitat quality and threats.

- If resources permit, a more intensive level would involve demographic monitoring of the Drooping Trillium population trend based on life stages, seedling- establishment, mortality and other factors. Intensive monitoring may be considered for critical sites with a high-level of threat, public land sites that have qualified staff available to conduct annual monitoring and any re-introduction sites. At present, both extant populations of Drooping Trillium should receive this intensive level of monitoring.

Evaluation of the recovery effort should be measured by the following criteria:

- There is no loss of extant populations. Populations are increasing or stable in size.

- There is no increase in anthropogenic disturbance (as determined from monitoring data), and threats are being addressed by 2014:

- monitoring program developed and initiated by 2012;

- key knowledge gaps relating to threats addressed by 2013;

- threats prioritized and mitigation plans developed by 2014; and,

- threat abatement measures initiated in 2014.

- Communications products are produced and distributed to landowners and land managers starting in 2013.

- Where feasible, reintroduction is initiated at suitable or restored historical sites by 2016.

Evaluation of specific actions taken to restore Drooping Trillium populations and their Carolinian woodlands habitat should be measured against specific steps and anticipated effects. Evaluation would involve determining whether the action was actually undertaken as prescribed and whether the anticipated effect of the action was realized. Monitoring and evaluation results should be provided in annual reports made publicly accessible by the responsible jurisdictions.

2.5 Area for consideration in developing a habitat regulation

Under the ESA, a recovery strategy must include a recommendation to the Minister of Natural Resources on the area that should be considered in developing a habitat regulation. A habitat regulation is a legal instrument that prescribes an area that will be protected as the habitat of the species. The recommendation provided below by the authors will be one of many sources considered by the Minister when developing the habitat regulation for this species.

In establishing the description of habitat to be considered for regulation, several factors were taken into consideration. Drooping Trillium has a very limited distribution in Ontario. The two extant occurrences are found in deciduous forests on well-drained loamy soils along fluvial systems that are believed to have high water tables. Drooping Trillium has likely occupied these sites as long as these conditions have existed and it is unlikely that much change in population sizes or location will occur as long as the environmental variables remain relatively constant. However, regular monitoring of the Sydenham River occurrence has found that population numbers are quite variable from year to year (Woodliffe pers. comm. 2009), probably due to annual climatic variations.

Because of the extremely low number of extant occurrences and the lack of knowledge of the importance of hydrological influence on the maintenance of Drooping Trillium habitat, it is recommended that the precautionary principle be applied in the regulation of the habitat. Given that the species does not occupy all apparently suitable habitat at the extant sites, it is recommended that the area occupied by the plants and the full extent of surrounding habitat required to protect the hydrological regime allowing for potential dispersal and population expansion, be prescribed as habitat in the regulation. Therefore, the area prescribed as habitat in a regulation for Drooping Trillium should be a composite area delineated by applying the following two criteria:

- A distance of 120 m from the outer limits of the area occupied by Drooping Trillium plants in order to protect the hydrological regime.

footnote 6 - The full extent of the Ecological Land Classification (ELC) ecosite (Lee et al. 1998, Lee 2009) polygon within which a population occurs.

The precautionary principle is applied here in recommending the 120 m buffer in the absence of site-specific hydrological studies which would provide better delineation of the area required to maintain the hydrological regime of the habitat. As new information on the species' habitat requirements and site-specific characteristics, such as hydrology, become available, these attributes should be used to refine the habitat definition. In particular, if it is demonstrated that a different area (larger, smaller, different shape) is necessary to protect the hydrological regime upon which the species depends, the habitat regulation should be revised to reflect this.

Historic occurrences have been extirpated, probably primarily due to habitat loss, nevertheless there appears to be a considerable amount of suitable unoccupied habitat within this species' range in Ontario. It is therefore recommended that the habitat regulation for Drooping Trillium be flexible enough to include repatriation or introduction sites that are necessary or beneficial for recovery. It should be noted that the species may spread through the dispersal of propagules downstream during flood events in the riparian habitats it occupies. Habitat regulation should therefore be flexible enough to allow for the future inclusion of newly colonized sites.

Drooping Trillium is occasionally cultivated for horticulture. It is recommended that horticultural populations be excluded from regulation.

Glossary

Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC): The committee responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Canada.

Committee on the Status of Species at Risk in Ontario (COSSARO): The committee established under section 3 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Ontario.

Conservation status rank: A rank assigned to a species or ecological community that primarily conveys the degree of rarity of the species or community at the global (G), national (N) or sub-national (S) level. These ranks, termed G-rank, N-rank and S-rank, are not legal designations. The conservation status of a species or ecosystem is designated by a number from 1 to 5, preceded by the letter G, N or S reflecting the appropriate geographic scale of the assessment.

The numbers mean the following:

1 = critically imperilled

2 = imperilled

3 = vulnerable

4 = apparently secure

5 = secure

Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA): The provincial legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Ontario.

Forb: A broad-leaved, non-woody plant other than a grass, sedge or rush.

Species at Risk Act, 2007 (SARA): The federal legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Canada. This act establishes Schedule 1 as the legal list of wildlife species at risk to which the SARA provisions apply. Schedules 2 and 3 contain lists of species that at the time the act came into force needed to be reassessed. After species on Schedule 2 and 3 are reassessed and found to be at risk, they undergo the SARA listing process to be included in Schedule 1.

Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) List: The regulation made under section 7 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that provides the official status classification of species at risk in Ontario. This list was first published in 2004 as a policy and became a regulation in 2008.

References

Augustine, D.J. and L.E. Frelich. 1998. Effects of White-tailed Deer on Populations of an Understory Forb in Fragmented Deciduous Forests. Conservation Biology, 12(5): 995-1004

Bickerton, H. 2003. (Draft) Monitoring Protocol for Pitcher’s Thistle (Cirsium pitcheri) – Dune Grasslands. Pitcher’s Thistle – Lake Huron Dune Grasslands Recovery Team. Manuscript.

Bohlen, P.J., S. Scheu, C.M. Hale, M.A. McLean, S. Migge, P.M. Groffman and D. Parkinson, 2004. Non-native invasive earthworms as agents of change in northern temperate forests. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 2(8): 427-435.

Bratton, S.P., J.R. Hapeman and A.R. Mast. 1994. The Lower Susquehanna River gorge and floodplain (USA) as a riparian refugium for vernal, forest-floor herbs. Conservation Biology, 8(4): 1069-1077.

Case Jr., F.W. 2002. Trillium. In Magnoliophyta: Liliidae: Liliales and Orchidales. Vol. 26 of Flora of North America north of Mexico. ed. Flora of North America Editorial Committee, 90-117. New York: Oxford University Press.

COSEWIC. 2009. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Drooping Trillium Trillium flexipes in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 31 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). [link no longer active]

DeMars, B.G. and R.E.J. Boerner. 1995. Mycorrhizal dynamics of three woodland herbs of contrasting phenology along topographic gradients. American Journal of Botany 82(11): 1426-1431.

Dextrase, A.J., S.K. Staton and J.L. Metcalfe-Smith. 2003. National Recovery Strategy for Species at Risk in the Sydenham River: An Ecosystem Approach. National Recovery Plan No. 25. Recovery of Nationally Endangered Wildlife (RENEW). Ottawa, Ontario. 73 pp.

Gleason, H.A., and A. Cronquist. 1991. Manual of Vascular Plants of Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada, 2nd ed. New York: The New York Botanical Gardens.

Harris, A.G. and R.F. Foster. 2008. Appendix 3. Summary of 2007 Field Surveys for Drooping Trillium (Trillium flexipes). Confidential appendix to COSEWIC status report. 13 pp.

Jalava, J.V. and P. Mansur. 2008. National Recovery Strategy for Carolinian Woodlands and Associated Species at Risk, Phase II: Part 1 – Implementation. Draft 5, September 30, 2008. Carolinian Canada Coalition, London, Ontario. vii + 124 pp.

Jalava, J.V., J.D. Ambrose and N.S. May. 2008. National Recovery Strategy for Carolinian Woodlands and Associated Species at Risk: Phase I. Draft 10 – March 31, 2008. Carolinian Canada Coalition and Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, London, Ontario. viii + 75 pp.

Lee, H. 2009. 2009 Vegetation Type List - Catalogue 8 (Ecological Land Classification for Southern Ontario). Unpublished Excel List. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Southern Science and Information Section, London, Ontario.

Lee, H., W. Bakowsky, J. Riley, J. Bowles, M. Puddister, P. Uhlig and S. McMurray. 1998. Ecological Land Classification for Southern Ontario: First Approximation and Its Application. SCSS Field Guide FG-02. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. 225 pp.

McLeod, David. 1996. Status report on the Drooping Trillium, Trillium flexipes, in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. 49 pp.

NHIC (Natural Heritage Information Centre). 2011. Species Lists, Element Occurrence and Natural Areas databases and publications. Natural Heritage Information Centre, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Peterborough, Ontario. Electronic databases.

NatureServe. 2011. NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life [web application]. Version 4.5. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available http://www.natureserve.org/explorer. (Accessed: August 8, 2005).

OMNR (Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources). 2002. Ontario Wetland Evaluation System, Southern Manual, covering Hill’s Site Regions 6 and 7. Third Edition, revised December 2002. MNR Warehouse #50254-1.

Patrick, T.S. 1984. Trillium sulcatum (Liliaceae), a new species of the Southern Appalachians. Brittonia 36(1): 26-36.

Ransom-Hodges, A. 2006. Drooping Trillium (Trillium flexipes). Canadian Biodiversity series, McGill University. On-line document: http://biology.mcgill.ca/undergra/c465a/biodiver/2002/drooping-trillium/trillium_flexipes.htm [link no longer active].

TRRT(Thames River Recovery Team). 2007. Thames River Recovery web site: http://www.thamesriver.on.ca/Species_at_Risk/species_at_risk.htm [link is inactive].

Woodliffe, P.A. 2009. Personal communications with J. Jalava, February – March 2009. District Ecologist, OMNR Aylmer District, Chatham Area Office, Chatham, Ontario.

Recovery strategy development team members

Table 3. Recovery strategy development team members

The recovery strategy was developed by Jarmo Jalava and John Ambrose under the direction of the following Recovery Team members:

| Name | Affiliation and location |

|---|---|

| Roxanne St. Martin (Co-chair) | Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources |

| Michelle Kanter (Co-chair) | Carolinian Canada Coalition |

| Dawn Bazely | York University |

| Jane Bowles | University of Western Ontario |

| Barb Boysen | Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources |

| Dawn Burke | Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources |

| Peter Carson | Private Consultant / Ontario Nature |

| Ken Elliott | Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources |

| Mary Gartshore | Private Consultant |

| Ron Gould | Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources |

| Karen Hartley | Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources |

| Steve Hounsell | Ontario Power Generation |

| Jarmo Jalava | Carolinian Canada Coalition |

| Donald Kirk | Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources |

| Daniel Kraus | Nature Conservancy of Canada |

| Nikki May | Carolinian Canada |

| Gordon Nelson | Carolinian Canada Coaltion / University of Waterloo |

| Michael Oldham | Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources |

| Michael Peppard | Conservation organization (NGO) |

| Bernie Solymar | Private Consultant |

| Tara Tchir | Upper Thames River Conservation Authority |

| Kara Vlasman | Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources |

| Allen Woodliffe | Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources |

Footnotes

- footnote[1] Back to paragraph In this recovery strategy, the term "occurrence" is used in the sense of "element occurrence", which is the standard spatial definition for "an area of land and/or water in which a species…is, or was present" (NatureServe 2010). An occurrence may contain one or more "populations" or sub-populations, as long as landscape features and species biology allow for genetic exchange between the populations. The term "population" is used more generically throughout this recovery strategy (and may thus apply to a local population or the entire provincial population, depending on the context).

- footnote[2] Back to paragraph The two historic occurrences in Essex are covered by the same shading in Figure 1.

- footnote[3] Back to paragraph The habitat at the historical McGillivray Township site still appears to be relatively intact and may hold the most promise for eventual re-discovery of a population last reported over 100 years ago.

- footnote[4] Back to paragraph There is only one known extant occurrence that is entirely on private land with the other being partly on private land. However, if additional populations are discovered through inventory or if suitable habitat for reintroduction is found, these might also be priority sites for acquisition or conservation easements.

- footnote[5] Back to paragraph Additional information on these various strategies and action plans can be found at the following web sites: www.carolinian.org [link is inactive] (Carolinian Canada Coalition conservation action plans), http://sydenhamriver.on.ca/index.htm (Sydenham River)

- footnote[6] Back to paragraph The recommended 120 m distance is consistent with policy protecting adjacent lands of provincially significant wetlands (OMNR 2002).