Eastern Banded Tigersnail recovery strategy

Read the recovery strategy for the Eastern Banded Tigersnail, a species at risk in Ontario.

About the Ontario recovery strategy series

This series presents the collection of recovery strategies that are prepared or adopted as advice to the Province of Ontario on the recommended approach to recover species at risk. The Province ensures the preparation of recovery strategies to meet its commitments to recover species at risk under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA) and the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk in Canada.

What is recovery?

Recovery of species at risk is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened, or extirpated species is arrested or reversed, and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of a species’ persistence in the wild.

What is a recovery strategy?

Under the ESA a recovery strategy provides the best available scientific knowledge on what is required to achieve recovery of a species. A recovery strategy outlines the habitat needs and the threats to the survival and recovery of the species. It also makes recommendations on the objectives for protection and recovery, the approaches to achieve those objectives, and the area that should be considered in the development of a habitat regulation. Sections 11 to 15 of the ESA outline the required content and timelines for developing recovery strategies published in this series.

Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for endangered and threatened species within one or two years respectively of the species being added to the Species at Risk in Ontario list. Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for extirpated species only if reintroduction is considered feasible.

What’s next?

Nine months after the completion of a recovery strategy a government response statement will be published which summarizes the actions that the Government of Ontario intends to take in response to the strategy. The implementation of recovery strategies depends on the continued cooperation and actions of government agencies, individuals, communities, land users, and conservationists.

For more information

To learn more about species at risk recovery in Ontario, please visit the Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks Species at Risk webpage.

Recommended citation

Wyshynski, S., A.R. Eads and A. Nicolai. 2019. Recovery Strategy for the Eastern Banded Tigersnail (Anguispira kochi kochi) in Ontario. Ontario Recovery Strategy Series. Prepared for the Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks, Peterborough, Ontario. v + 29 pp.

ISBN 978-1-4868-3510-2 (HTML)

ISBN 978-1-4868-3511-9 (PDF)

Content (excluding illustrations) may be used without permission with appropriate credit to the source, except where use of an image or other item is prohibited in the content use statement of the adopted federal recovery strategy.

Cette publication hautement spécialisée « Recovery strategies prepared under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 », n’est disponible qu’en anglais en vertu du Règlement 411/97 qui en exempte l’application de la Loi sur les services en français. Pour obtenir de l’aide en français, veuillez communiquer avec recovery.planning@ontario.ca.

Authors

Sarah Wyshynski – Ecological Consultant

Angela Eads – Trent University

Annegret Nicolai – Université Rennes 1, Biological Station Paimpont

Declaration

The recovery strategy for the Eastern Banded Tigersnail was developed in accordance with the requirements of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA). This recovery strategy has been prepared as advice to the Government of Ontario, other responsible jurisdictions and the many different constituencies that may be involved in recovering the species.

The recovery strategy does not necessarily represent the views of all of the individuals who provided advice or contributed to its preparation, or the official positions of the organizations with which the individuals are associated.

The recommended goals, objectives and recovery approaches identified in the strategy are based on the best available knowledge and are subject to revision as new information becomes available. Implementation of this strategy is subject to appropriations, priorities and budgetary constraints of the participating jurisdictions and organizations.

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this strategy.

Responsible jurisdictions

Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks

Environment and Climate Change Canada – Canadian Wildlife Service, Ontario

Parks Canada Agency

Executive Summary

The Eastern Banded Tigersnail is a large, terrestrial snail that has distinctive dark banding around its yellow-brown shell with an opening in the centre when viewed from below. There can be variations in shell size, thickness, and colour, as well as the visibility of bands, especially on weathered or older snails. The Eastern Banded Tigersnail hibernates from early October until April, and lays eggs in late spring and late summer. Terrestrial snails in general have a low physiological resistance to fluctuating environmental factors and a very low dispersal ability. The Eastern Banded Tigersnail is part of the unique faunas of the Carolinian ecosystem, and has significance for ecosystem functioning, research, and conservation.

The species range extends south to Tennessee, east to Pennsylvania, and west to Missouri. In Ontario, the Eastern Banded Tigersnail remains only on Pelee Island and Middle Island in Lake Erie. The species is listed as endangered in Ontario under the Ontario’s Endangered Species Act, 2007 due to its small range, decline and loss of subpopulations, and habitat alteration and fragmentation.

Threats to the Canadian population include, but are not limited to: climate change, habitat loss and degradation, ecosystem modification because of invasive and non-native species, predation, competition and disturbance from recreational activities. Climate change is the most serious threat to the persistence of the Eastern Banded Tigersnail, and will increase the likelihood of severe storms, flooding, and habitat erosion. Habitat on Middle Island is already severely altered by overabundant native Double-crested Cormorants. Eastern Banded Tigersnails are likely to be further impacted by competition with introduced slugs, increased predation pressure from Wild Turkeys and introduced snails, modifications to soil and leaf litter due to introduced plants and earthworms, as well as fire. Increasing tourism (trail development and traffic) may also impact the Eastern Banded Tigersnail, as well as pesticide run-off.

The recommended recovery goal is to maintain the current subpopulations of the Eastern Banded Tigersnail throughout their current range in Ontario, by maintaining, protecting and enhancing habitat, and reducing other threats. The recommended protection and recovery objectives are to:

- Secure protection for Eastern Banded Tigersnail habitats through active engagement with all levels of government and landowners within the species range;

- Implement a monitoring program for Eastern Banded Tigersnail subpopulations, habitats and threats on Pelee Island and Middle Island, including surveys of suitable habitat;

- Assess and mitigate threats to all known sites in Ontario; and

- Address knowledge gaps related to biology, habitat requirements and threats that may assist in recovery efforts.

Specific steps are recommended to achieve each of the protection and recovery objectives.

Given that Eastern Banded Tigersnails have an extremely limited distribution in Ontario, low dispersal ability, and that information pertaining to habitat use throughout various life stages and seasons is lacking, it is recommended that a precautionary approach be applied in defining habitat for the Eastern Banded Tigersnail. The area to be defined as habitat should include sufficient suitable habitat necessary for mating, nesting, foraging, aestivation and hibernation, along with dispersal. It is therefore recommended that the entire Ecological Land Classification (ELC) ecosite polygon occupied by an extant subpopulation of Eastern Banded Tigersnail be prescribed as habitat in a habitat regulation. In addition, it is recommended that a buffer of 50 m be added to the ELC ecosite polygon to account for dispersal into neighbouring habitat, reduce edge effects and maintain microhabitat conditions important to Eastern Banded Tigersnails. This 50 m buffer of suitable habitat around the ELC ecosite polygon takes into account the longest dispersal distance measured (32 m) in similar sized species (Edworthy et al. 2012), along with ensuring protection of habitat that may be used by snails at different times of year. Habitat known to be unsuitable (e.g., roads, lakes) for Eastern Banded Tigersnails can be excluded from this buffer. Information on spatial limits of habitat used by the Eastern Banded Tigersnail is lacking. Using a contiguous ecological area to define habitat for the Eastern Banded Tigersnail increases the likelihood that all habitat elements required by the species are included.

1.0 Background information

1.1 Species assessment and classification

The following list is assessment and classification information for the Eastern Banded Tigersnail (Anguispira kochi kochi). Note: The glossary provides definitions for abbreviations and technical terms in this document.

- SARO List Classification: Endangered

- SARO List History: Endangered (2018)

- COSEWIC Assessment History: Endangered (2017)

- SARA Schedule 1: No schedule, no status

- Conservation Status Rankings: G-rank: G5; N-rank: N3; S-rank: S1S2

1.2 Species description and biology

Species description

The Eastern Banded Tigersnail (Anguispira kochi kochi) is a large terrestrial snail (adult shell width up to 2.5 cm). The yellow or brown shell is a robust, globular shape with broad whorls forming a spiral, and distinctively encircled by two dark longitudinal bands (Figure 1). The shell also has shallow radial grooves (striae) on the surface (Grimm et al. 2010, Pilsbry 1948). There can be large variation in shell size, thickness, and colouration, as well as the visibility of banding and grooves (Figure 1). Weathered, older animals can have a deteriorated periostracum (outer covering of the shell), losing the distinctive colour and textural features of the shell; however, colour bands are visible on the inside of the shell (COSEWIC 2017). The opening of the shell is slightly thickened in adults, and the umbilicus (the hollow in the underside around which the shell coils) is open and large. The animal is mostly grey, though the head and the foot may be slightly orange-red to brown (Figure 1) and can produce a slightly orange mucus when disturbed. When aestivating and hibernating the shell is closed with an orange or white mucus foam (COSEWIC 2017).

Species biology

The Eastern Banded Tigersnail is a pulmonate (air-breathing), egg-laying simultaneous hermaphrodite (possesses both male and female reproductive organs) terrestrial snail (Pilsbry 1948). There is little else known about the life history of this species in Canada but based on field observations and similarities to related gastropods, the following can be assumed. Sexual maturity is reached after two to three years and their lifespan is possibly up to 10 years (COSEWIC 2017). Mating likely occurs multiple times per year, in mid-spring and mid-summer, with egg-laying in late spring and late summer when egg clutches of unknown size are deposited in shallow holes excavated in moist soil (Barker 2001).

Eastern Banded Tigersnails have been observed feeding on dead plant material, may also feed on micro-fungi, and are often found in the leaf litter and under decaying logs (COSEWIC 2017). Terrestrial snails require calcium from the soil for different physiological processes, such as growth, reproduction and heat protection (Wäreborn 1979, Hotopp 2002, Nicolai et al. 2013).

Snails have a low physiological resistance to fluctuating environmental factors, such as temperature and humidity, and the availability of moist refuges that buffer environmental fluctuations is a key limiting factor for population growth and persistence of most terrestrial snails (Burch and Pearce 1990). Snails are prone to dehydration in summer and may become dormant during prolonged periods of drought. They have developed physiological processes to maintain survival; however, unusually long heat and drought periods increase mortality rates (Nicolai et al. 2011). Snails will hibernate from early October until April, when they may take shelter in refuges insulated by snow to buffer them from freezing during winter (Nicolai and Ansart 2017). Terrestrial gastropods use various behavioural and physiological strategies to survive sub-zero temperatures (Ansart and Vernon 2003).

The Eastern Banded Tigersnail has a very low dispersal ability and is very unlikely to colonize new areas unassisted. Species of similar size are known to move between 80 cm (e.g., Anguispira alternata) and 230 cm (e.g., Mesodon thyroidus) per day within a home range of 40 m2 to 800 m2 respectively (Pearce 1990), have a net displacement of 32 m over three years (e.g., Allogona townsendiana, Edworthy et al. 2012), or have home ranges greater than 50 m2 but return to hibernation sites (e.g., Allogona profunda, Blinn 1963). Passive dispersal by flooding of rivers (Vagvolgyi 1975) or transportation by birds (Kawakami et al. 2008) is possible but has not been documented in this species. There is no evidence that the species is transported by humans.

1.3 Distribution, abundance and population trends

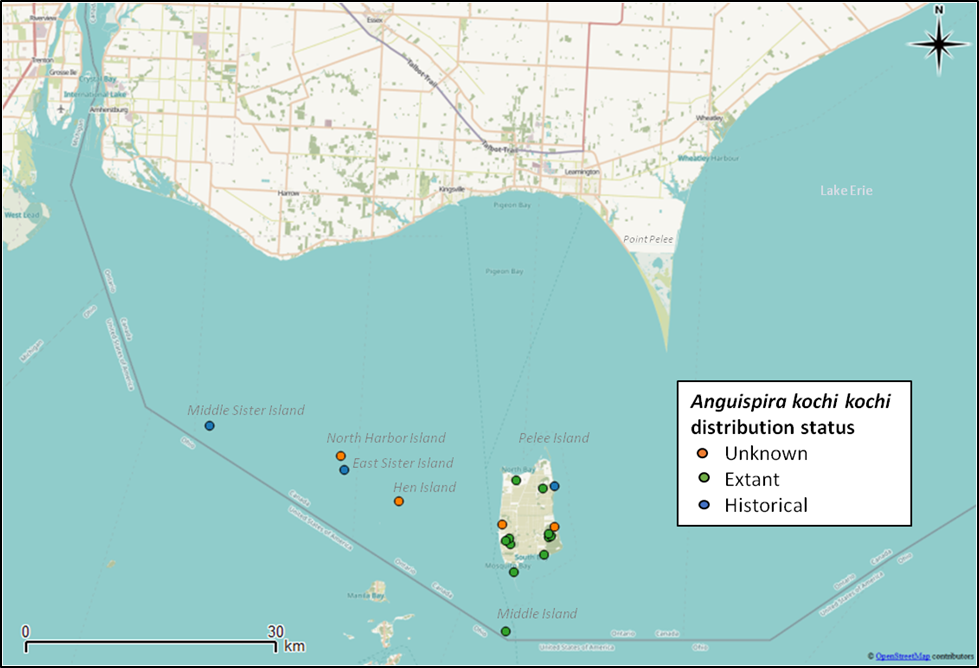

Two subspecies of Anguispira kochi are currently recognized in Canada: A. k. kochi (the Eastern Banded Tigersnail) on the Lake Erie islands in Ontario, and A. k. occidentalis (the Western Banded Tigersnail) in British Columbia (Pilsbry 1948, COSEWIC 2017). The extent of occurrence (i.e., the zone encompassing all the known present occurrences) of the Eastern Banded Tigersnail in Canada is 102 km2, though much of this calculated area is in Lake Erie, while the actual area of occupancy is estimated to be 36 km2 (COSEWIC 2017). Within Ontario, extant (i.e., existing or surviving) subpopulations of the Eastern Banded Tigersnail were observed on Pelee Island and Middle Island in Lake Erie during widespread surveys undertaken in 2013 to 2015 (Figure 2). The most recent genetic information suggests little divergence between these subpopulations, though they are separated by approximately five kilometres of open water (COSEWIC 2017). Within each subpopulation, there is the possibility of genetic exchange among individuals, assuming habitat patches are currently or could be connected in the future. However, habitat patches (only known in conservation properties) on Pelee Island are fragmented with some isolated by up to four kilometres.

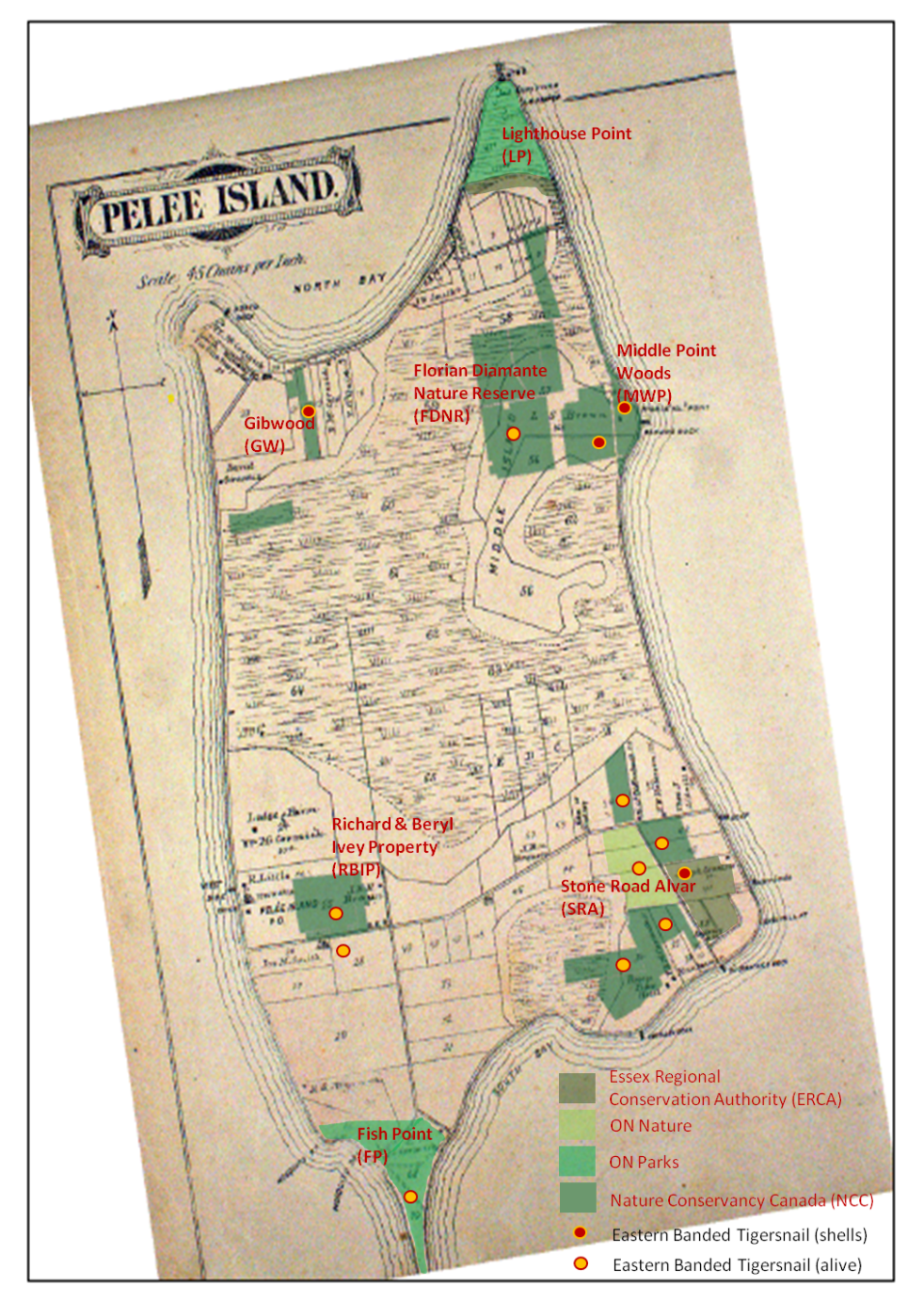

From 2016 to 2018, annual comprehensive surveys were conducted across Pelee Island for snail species of conservation concern. Live Eastern Banded Tigersnails were observed at Fish Point Provincial Nature Reserve, Ontario Nature Stone Road Alvar property, Shaughnessy Cohen Memorial Savanna (eastern Nature Conservancy of Canada (NCC) Stone Road Alvar property), Florian Diamante Nature Reserve (NCC) and the Richard and Beryl Ivey Nature Reserve (NCC). No live snails were found in the Gibwood property (NCC), the Essex Region Conservation Authority (ERCA) Stone Road Alvar property or the southern and western NCC Stone Road Alvar properties from 2012 to 2015, but live individuals or fresh shells of Eastern Banded Tigersnails were found in 2016 or 2018, highlighting the cryptic nature of terrestrial snails. Only old, weathered shells have been found in Middle Point Woods (NCC) since 2006, when significant forest flooding occurred. The Krestel property (northern NCC Stone Road Alvar property) and Winery Woods likely still host a small number of Eastern Banded Tigersnails even though no live individual has been observed in either location since 2006 and 2013, respectively. Habitat has not been disturbed on these conservation properties, whereas habitat conditions may have changed through human activities on the East Park campground and private land (not recently surveyed) where shells were last found in 1995 and 1997, respectively. Historically, Pelee Island was composed of four bedrock islands separated by marshland; however, to develop the island for agriculture in the 1890s, the marshes were dredged and the water pumped out to the lake (Figure 3). The distribution of the Eastern Banded Tigersnail on Pelee Island is determined by this historical segregation, as well as by current and historical activities on each property, such as logging, grazing and agriculture).

The subpopulation on Middle Island (part of Point Pelee National Park) may have been dramatically reduced since the early 1980s due to habitat destruction from the overabundant Double-crested Cormorants (Phalacrocorax auritus) (Dobbie and Kehoe 2008). Historically, Eastern Banded Tigersnails were found on many other western Lake Erie islands (Clapp 1916, Goodrich 1916, Ahlstrom 1930 and see collection records in COSEWIC 2017). However, no live Eastern Banded Tigersnails have been sighted on East Sister Island or on Middle Sister Island since specimens were collected there in 1916 and 1996, respectively (COSEWIC 2017). North Harbour Island and Hen Island are not accessible due to private ownership and so have not been recently surveyed. Habitat on East Sister and Middle Sister Islands was also heavily degraded by the Double-crested Cormorant, while North Harbour Island has been developed and little natural habitat remains. The Eastern Banded Tigersnail is considered extirpated on these three islands (COSEWIC 2017). Only Hen Island still harbours intact forest that is suitable habitat for the species. In 1991, shells were collected near Alvinston, Lambton County, on what is now a property of the St. Clair River Conservation Authority and recorded as Eastern Banded Tigersnails. However, the specimens for this record were lost and presumed to be erroneous (Forsyth, pers. comm., 2017-2018). The property has been surveyed repeatedly in 2015 and 2017; no shells were found, and habitat conditions appear unsuitable for this species.

The Canadian population of Eastern Banded Tigersnails was estimated at about 800,000 mature individuals in 2015 (COSEWIC 2017). Recruitment has been observed in most sites where the species was found alive. In 2018, the densest occurrence of Eastern Banded Tigersnails was found in the Fish Point Provincial Nature Reserve, which has a much higher abundance (mean 4.1 snails/m2) compared to all the other sites (e.g., Richard and Beryl Ivey Nature Reserve, 0.7 snails/m2). Anthropogenic pressure (logging, grazing, and agriculture) on Pelee Island might have reduced abundance in the other conservation properties compared to Fish Point. The subpopulation of Eastern Banded Tigersnails on Middle Island was broadly estimated to be between 4,000 and 32,000 individuals in 2015. In the three monitoring plots on the island, mean abundance was 0.3 snails/m2 in 2015, 0.9 snails/m2 in 2016 and 1.8 snails/m2 in 2017. The small increases in abundance may indicate a recovery related to Double-crested Cormorant culls that have occurred annually since 2008 or may simply be due to natural fluctuations in population size.

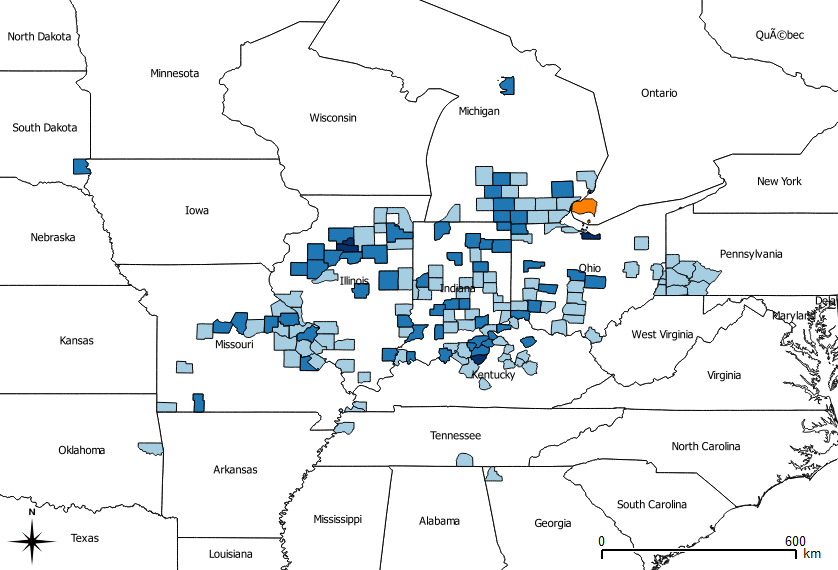

The distribution of the Eastern Banded Tigersnail in the USA extends from Tennessee in the south, Pennsylvania to the east, west to Missouri, and across Michigan (Hubricht 1985 and collection records in COSEWIC 2017, Figure 4). However, increased genetic diversity and population augmentation via immigration from these populations outside of Canada are not possible due to Lake Erie acting as a barrier.

NatureServe (2018) provides the following ranks for US states:

- US states adjoining southwestern Ontario:

Michigan: SU; Pennsylvania: S3; Ohio: SNR; New York: not present - Other US states where Eastern Banded Tigersnail occurs:

Illinois: SNR; Indiana: SNR; Kentucky: S2; West Virginia: S1; Missouri: SNR; Tennessee: S2

- SNR: not ranked sub-nationally

- SU: unrankable

- S1: critically imperiled sub-nationally

- S2: imperiled sub-nationally

- S3: vulnerable sub-nationally

- S4: apparently secure sub-nationally

1.4 Habitat needs

In Canada, the Eastern Banded Tigersnail inhabits mesic mature hardwood or mixed-wood forests. Goodrich (in Pilsbry 1948) characterizes the Eastern Banded Tigersnail as being “one of the typical molluscs of the old forest, and seldom found even in thick second-growth timber”. The Eastern Banded Tigersnail has been observed in Chinquapin Oak-Nodding Onion treed alvar and dry-fresh Hackberry deciduous forest on Middle Island and on Pelee Island, as well as in dry-fresh Sugar Maple-White Ash deciduous forest and dry Black Oak woodland at Fish Point on Pelee Island (COSEWIC 2017). These habitats have either rocky ground consisting of limestone with herbaceous vegetation cover (alvar) or sandy, humus-rich soil with a substantial leaf litter layer (10-20 cm). The forests where the species is found also have decaying logs and wood material. Leaf litter, logs and humus-rich soil provide temperature-buffered and moist microhabitat sites for hibernation, aestivation and egg laying, while limestone and calcium-rich plants provide nutrients. About 115 ha out of the total 788 ha of protected land (conservation properties of NCC, Ontario Nature, ERCA, Ontario Parks, Pelee Island Winery) on Pelee and Middle Islands (Parks Canada) represent suitable habitat for the species (COSEWIC 2017).

When Pelee Island was dredged and developed for agriculture, habitat loss was high due to significant deforestation. About 15 to 20 percent of the natural forest cover is still intact, most of which is under management by the NCC or the Ministry of Environment Conservation and Parks (MECP). No native snails or slugs were found in former marshland (e.g., cultivated fields or small cultured woodlots between fields) on Pelee Island during surveys from 2013 to 2015, indicating that these environments do not represent suitable habitat and do not act as habitat or movement corridors.

The climate of the Lake Erie islands is much warmer than expected for its latitude because of the moderating effect of Lake Erie, and two-thirds of the year they are frost-free. This warmer climate plays an extremely important role in the persistence of flora and fauna at their northern range limits (North – South Environmental Inc. 2004). The warmer climate also leads to increased snowfall due to a higher precipitation rate, and this thicker snow cover is imperative for Eastern Banded Tigersnail winter survival when temperature variations are high.

1.5 Limiting factors

The Eastern Banded Tigersnail persists in small isolated forested habitat patches on Middle and Pelee Islands in Lake Erie. Eastern Banded Tigersnails have a very low dispersal ability and without corridor habitats at a suitable micro-scale, they are very unlikely to colonize new areas unassisted, to escape short-term threats or to recover from negative impacts (Nicolai and Ansart 2017). Fragmentation of habitat or encroachment into habitat due to agriculture, roads and water barriers all increase dispersal difficulty and restrict gene flow among subpopulations.

Eastern Banded Tigersnails have a low physiological resistance to fluctuating environmental factors, such as temperature and humidity, and the availability of moist refuges that buffer environmental fluctuations is a key limiting factor for population growth and persistence of most terrestrial snails (Burch and Pearce 1990). Their adaptability to changing climate conditions might be limited (Nicolai and Ansart 2017). Eastern Banded Tigersnails are restricted to mesic mature hardwood or mixed-wood forests and alvars, which are limited habitats across south-western Ontario. The species requires specific habitat and climate conditions to avoid dehydration in hot and dry periods and to hibernate through winter.

1.6 Threats to survival and recovery

The broad threats to the ongoing persistence of snail subpopulations are habitat destruction or modification, increased predation or competition, and significant weather events and climate change. These threats co-occur and can interact to increase the overall negative impact on snails; these cumulative impacts substantially elevate the level of overall threat for the Eastern Banded Tigersnail.

Climate change and severe weather

Climate change represents a significant but poorly understood threat to Eastern Banded Tigersnails. Southwestern Ontario is projected to have more extreme weather events including droughts, floods, and temperature extremes under climate change models (Varrin et al. 2007). Extreme temperatures are more likely, which result in more frequent and severe spring frosts (Augspurger 2013). There is high snail mortality when snow cover is absent (Nicolai and Ansart 2017). Snails are vulnerable to increasing average temperatures accompanied by increased occurrences of drought (Pearce and Paustian 2013), which can cause high mortality in some species that rely on shelter (Nicolai et al. 2011). With increased precipitation due to climate change, storms on Middle Island are predicted to become more violent, and erosion and flooding of forest habitats on Pelee Island are likely to occur more often, last longer, and disturb larger areas. Eastern Banded Tigersnails are found near the eastern shore of Pelee Island, which is being gradually eroded (COSEWIC 2017); the species is likely already affected by storm and flood damage, as only weathered shells have been found in multiple sites where these weather events take place. These threats need to be considered when assessing potential sites for recolonization.

Ecosystem and habitat modification

Nesting colonies of Double-crested Cormorants have increased dramatically on the Lake Erie islands since the early 1980s and are presumed to be the main reason for the extirpation of Eastern Banded Tigersnail on Middle Sister and East Sister Islands. Double-crested Cormorants have severely decreased the available forest habitat on Middle Island (Dobbie and Kehoe 2008) and have modified soil chemistry and community assemblages (North – South Environmental Inc. 2004; Boutin et al. 2011). Low soil pH and high soil salinity disturb physiological processes in snails. The change in plant diversity and density might reduce nutritional resources and degrade microhabitat structure for snails. Double-crested Cormorant culls have occurred on Middle Island since 2008 (Thorndyke and Dobbie 2013), but their effects here still need to be verified (Guillaumet et al. 2014).

There are several highly invasive plants on the islands in south-western Lake Erie, including Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata) in forests and grasses of the family Poaceae in alvars. For instance, Garlic Mustard has been observed displacing native vegetation and altering soil nutrient cycles, thereby slowing restoration (Catling et al. 2015). Invasive plants are actively controlled using herbicides, mechanical control or prescribed burns. However, the impact of the invasive plants on the Eastern Banded Tigersnail is unknown (COSEWIC 2017).

Non-native earthworms have invaded parts of Canada relatively recently. They have been shown to have major impacts on ecosystems and could indirectly affect terrestrial snail communities (Norden 2010, Forsyth et al. 2016). Earthworms alter forest floor habitats by reducing or eliminating the natural leaf litter layer and digging up and mixing the mineral soil with the organic surface layer (Qiu and Turner 2017). The resulting changes in understory vegetation composition (Drouin et al. 2016) reduces available food plants and microhabitat for snails.

Invasive competitors and predators

Competition with exotic terrestrial gastropods is a potential threat (Whitson 2005, Grimm et al. 2010, Campbell et al. 2014) through aggression (Kimura and Chiba 2010), density effects and/or competition for food (Baur and Baur 1990b). The Dusky Arion (Arion subfuscus), Orange-banded Arion (Arion fasciatus), Grey Fieldslug (Deroceras reticulatum), and Grovesnail (Cepaea nemoralis) are present in the habitat of Eastern Banded Tigersnail, but their impacts are unknown (COSEWIC 2017). Additionally, predation by exotic carnivorous snails may be a threat to the Eastern Banded Tigersnail on Middle Island, as species of the Glass Snail genus Oxychilus were observed on Middle Island in 2013 (records MJO 40569a and ANi033e in the Forsyth-Nicolai Collection, Forsyth pers. comm. 2017-2018.). Wild Turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo) were introduced to Pelee Island in 2002, where they spread rapidly and are now naturalized with several flocks of more than 200 individuals. They are actively hunted in the spring. Similarly, Ring-necked Pheasants (Phasianus colchicus) were introduced to Pelee Island in the late 1920s for hunting. Both bird species are omnivorous and include snails in their diet (Sandilands 2005), and are known to disturb ground habitat by their intensive scratching. The impacts of these birds on snail subpopulations remain unstudied.

Human intrusions and disturbances

There has been a marked increase in tourism on Pelee Island since the ferry service expanded in 1992. The island attracts significant numbers of birders, photographers, tourists, hunters, and researchers, with annual visitation estimated to be 7,500 people at Fish Point alone (Ontario Parks 2005). Wide trails represent barriers for snail movement (Wirth et al. 1999). Moreover, trampling by pedestrians is a known threat for some snail species (Baur and Baur 1990a). Since visitors are only allowed on Middle Island from September to February, mostly a period of snail inactivity, their activities may not be a threat for Eastern Banded Tigersnails. Disturbance by targeted research activities for species of conservation concern appears to be low as researchers usually take care to minimize habitat disturbance. Specific gastropod research takes place in only a few monitoring plots within each habitat on Middle and Pelee Islands where snail stress is actively limited.

Fire has become an important management tool for forest and prairie conservation. Portions of the Stone Road Alvar on Pelee Island have been subjected to prescribed burns by Ontario Nature and ERCA in 1993, 1997, 1999, and 2005 (NCC 2008). There are plans by Ontario Nature for a burn in October 2019 to enhance snake habitat on parts of their Stone Road Alvar property (Horrigan, pers. comm., 2018) where the Eastern Banded Tigersnail also occurs. Burning directly and indirectly affects survival of litter-dwelling and soil invertebrates including terrestrial snails (Nekola 2002). Fire reduces and modifies organic substrates and residues (litter layer), which serve as both nutrients and shelter for these organisms (Bellido 1987). Fire can change the microclimate due to the sun warming post-burn bare soil and increasing soil evaporation (Knapp et al. 2009).

Transportation and service corridors

Conservation properties on Pelee Island are separated by roads, canals, and ditches. Snails are highly vulnerable when moving across roads, and rarely attempt to do so; as such, paved roads with high traffic densities fragment snail populations (Baur and Baur 1990a). Canals, ditches, paved and unpaved roads or tracks with both high and low traffic densities, or even a narrow footpath devoid of leaf litter, can all be barriers to snail dispersal (Baur and Baur 1990a; Wirth et al. 1999, Meadows 2002).

Pollution

Air- and water-borne pollution from roads (e.g., heavy metals and road salt) represents a potential threat to snails (Viard et al. 2004). However, traffic on Pelee Island is low and is absent on Middle Island. Agricultural effluents and herbicide use in the control of invasive plants in conservation properties on Pelee and Middle Islands may represent a threat for the Eastern Banded Tigersnail, though the impacts of pesticides on terrestrial gastropods are poorly understood. Laboratory studies have shown that exposure to some herbicides increases mortality of some snail species (Koprivnikar and Walker 2011) and could affect reproduction (Druart et al. 2011), thereby affecting population dynamics.

1.7 Knowledge gaps

Limited knowledge of the species distribution and biology, specifically diet, physiological responses to environmental factors, and interactions with exotic species may hinder the efficacy of protection strategies for the Eastern Banded Tigersnail. Research on the following knowledge gaps would contribute to a more complete understanding for the protection and recovery of this species and its habitat:

- population viability analysis and genetic diversity;

- life history traits: growth, reproduction, life span, dispersal;

- habitat requirements: diet, physico-chemical parameters in the soil and litter, habitat structure (physical elements, vegetation composition);

- interspecific interactions: especially the impact of exotic terrestrial gastropods, plants and earthworms through habitat changes or competition for food and shelter (density effects);

- physiological tolerances and adaptability: heat and cold resistance, responses to pesticides and changes in climatic conditions and soil characteristics;

- predation risk: predation impact of birds and carnivorous gastropods; and

- subpopulation-level responses to habitat management measures, such as mechanical vegetation-thinning and prescribed burns, through monitoring of changes in distribution, mortality, demography and re-colonization from buffer zones.

1.8 Recovery actions completed or underway

To date, no specific recovery actions have been implemented, though the regular monitoring of a few plots on Middle and Pelee Islands was initiated in 2015.

2.0 Recovery

2.1 Recommended recovery goal

The recommended recovery goal is to maintain the current subpopulations of Eastern Banded Tigersnail throughout their current range in Ontario, by maintaining, enhancing and protecting habitat, and reducing other threats.

2.2 Recommended protection and recovery objectives

- Secure protection for Eastern Banded Tigersnail habitats through active engagement with all levels of government and landowners within the species’ range.

- Implement a monitoring program for Eastern Banded Tigersnail subpopulations, habitats and threats on Pelee Island and Middle Island, including surveys of suitable habitat.

- Assess and mitigate threats to all known sites in Ontario.

- Address knowledge gaps related to biology, habitat requirements and threats that may assist in recovery efforts.

2.3 Recommended approaches to recovery

Table 1: Recommended approaches to recovery of the Eastern Banded Tigersnail in Ontario

| Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Short-term | Protection, Management | 1.1 Develop a habitat description or habitat regulation to provide clarity on the area defined as habitat for Eastern Banded Tigersnail in Ontario. | Threats:

|

| Necessary | Short-term | Protection, Management | 1.2 Identify existing and potential Eastern Banded Tigersnail habitat.

|

Threats:

|

| Necessary | Ongoing | Management, Stewardship | 1.3 Work with relevant agencies, organizations and landowners (NCC, Ontario Nature, ERCA, Parks Canada, MECP) to develop and implement habitat management and protection programs for Eastern Banded Tigersnail.

|

Threats:

|

| Necessary | Ongoing | Protection, Management, Stewardship | 1.4 Support the protection and securement of land important for Eastern Banded Tigersnail (lands owned and/or managed by NCC, ERCA, Ontario Nature, MECP). | Threats:

|

| Necessary | Ongoing | Education, Outreach, Communications, Stewardship | 1.5 Work with NCC, additional non-government organizations as well as government partners to increase public understanding and knowledge of Eastern Banded Tigersnail.

|

Threats:

|

| Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Short-term | Inventory and Monitoring | 2.1 Develop identification material to aid in accurate recognition of this species including how to distinguish it from other similar species. | Knowledge gaps:

|

| Critical | Short-term | Inventory and Monitoring | 2.2 Develop standardized protocol for Eastern Banded Tigersnail presence/absence surveys along with subpopulation inventorying and monitoring surveys. Protocol should include:

|

Knowledge gaps:

|

| Critical | Short-term | Inventory and Monitoring | 2.3 Develop standardized protocol for inventorying and monitoring habitat information at each site. Habitat parameters should include:

|

Threats:

|

| Necessary | Ongoing | Inventory and Monitoring | 2.4 Conduct yearly monitoring of current subpopulations (in conjunction with the ongoing yearly monitoring of Double-crested Cormorant nests and vegetation on Middle Island by Parks Canada), in addition to inventorying and monitoring habitat parameters at each site. | Knowledge gaps:

|

| Beneficial | Ongoing | Inventory and Monitoring | 2.5 Survey suitable habitats to find any unknown subpopulations of Eastern Banded Tigersnail. | Knowledge gaps:

|

| Beneficial | Ongoing | Inventory | 2.6 Engage volunteers (e.g., local naturalists, land stewards, experts) to undertake surveys in the search for this species to determine presence or absence.

|

Knowledge gaps:

|

| Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Ongoing | Protection, Management, Monitoring and Assessment | 3.1 Quantify and rate threats at each site to aid in identifying and prioritizing site-specific actions to reduce threats.

|

Threats:

|

| Necessary | Ongoing | Protection, Management, Monitoring and Assessment | 3.2 Assess and implement actions that are needed to protect Eastern Banded Tigersnails from predation by, and competition from, non-native species.

|

Threats:

|

| Necessary | Ongoing | Protection, Management, Monitoring and Assessment, Communication | 3.3 Assess and implement actions needed to protect Eastern Banded Tigersnails from habitat degradation and loss as a result of ecosystem modification (due to fire, invasive plants, earthworms and Double-crested Cormorants).

|

Threats:

|

| Necessary | Ongoing | Management, Assessment, Education, Communication, and Stewardship | 3.4 Assess and implement site-specific actions that are needed and appropriate to minimize damage to Eastern Banded Tigersnail habitat caused by human disturbances. This may include but not be limited to:

|

Threats:

|

| Critical | Ongoing | Management, Protection | 3.5 Identify protect and/or create refuge areas for snails to move into in times of extreme temperatures and/or droughts.

|

Threats:

|

| Critical | Ongoing | Management, Protection | 3.6 Identify Eastern Banded Tigersnail habitats that are more vulnerable to threats from flooding, erosion, fire and development.

|

Threats:

|

| Necessary | Ongoing | Management, Protection | 3.7 Identify habitat restoration and enhancement opportunities to increase and improve habitat availability.

|

Threats:

|

| Necessary | Ongoing | Management, Protection | 3.8 As knowledge gaps pertaining to habitat requirements are filled, re-evaluate management and protection actions. | Threats:

|

| Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Short-term | Research | 4.1 Engage the academic community to participate in researching knowledge gaps such as:

|

Knowledge gaps:

|

| Critical | Short-term | Research | 4.2 Monitor Eastern Banded Tigersnail activity (through mark-recapture studies) to determine home range size and dispersal ability, which will allow for better estimates of the amount of habitat required for snail survival. | Knowledge gaps:

|

| Critical | Short-term | Research | 4.3 Conduct habitat assessments at known sites to better identify key habitat features that could predict presence/absence of snails and allow for greater understanding of habitat requirements of the species. | Knowledge gaps:

|

| Critical | Short-term | Research | 4.4 Determine the degree Double-crested Cormorant colonies need to be managed to ensure persistence of snail subpopulations. | Threats:

|

| Critical | Short-term | Research | 4.5 Research the direct impact of prescribed burns on subpopulations (mortality, demography, recolonization) and indirect impacts (physiological and population-level responses to habitat changes) | Threats:

|

| Necessary | Ongoing | Research | 4.6 Investigate the impact of climate change on Eastern Banded Tigersnail subpopulations.

|

Threats:

|

| Beneficial | Ongoing | Research | 4.7 Research impacts of non-native terrestrial gastropods and earthworms on Eastern Banded Tigersnail and its habitat. | Threats:

|

| Necessary | Short-term | Research | 4.8 Research the effects of predation caused by introduced species and estimate potential mortality for Eastern Banded Tigersnail as a result of predation. | Threats:

|

| Beneficial | Short-term | Research | 4.9 Research the effects of pesticides (effluents from agriculture and gardens, and pesticides used to control invasive plants) on Eastern Banded Tigersnail. | Threats:

|

2.4 Area for consideration in developing a habitat regulation

Under the ESA, a recovery strategy must include a recommendation to the Minister of the Environment, Conservation and Parks on the area that should be considered in developing a habitat regulation. A habitat regulation is a legal instrument that prescribes an area that will be protected as the habitat of the species. The recommendation provided below by the author will be one of many sources considered by the Minister when developing the habitat regulation for this species.

The Eastern Banded Tigersnail has a very limited distribution in Ontario, with confirmed extant subpopulations only found on two Lake Erie islands (Middle Island and Pelee Island). Because of the extremely limited distribution (only a few locations on these islands) along with a very low dispersal ability, it is recommended that a precautionary approach be applied in defining habitat for Eastern Banded Tigersnails.

When overlaying Eastern Banded Tigersnail occurrences on vegetation maps (Ecological Land Classification [ELC] by Lee et al. 1998) of Pelee Island and Middle Island, an affinity for particular habitat types was shown (COSEWIC 2017). However, what knowledge we have for current habitat use is based on a small number of observations during seasonal annual surveys. How Eastern Banded Tigersnails use particular habitat patches, in different seasons, for various biological functions such as feeding and aestivation/hibernation, is unknown. Given the lack of information on habitat requirements, it is recommended that the regulated area include sufficient suitable habitat to maintain specific life functions throughout different seasons. In general, snail populations are typically made up of several hundred individuals heterogeneously distributed over a habitat patch. Using a contiguous ecological area to define habitat increases the probability that all habitat elements necessary for foraging, mating and nesting, aestivating and hibernating are included. It is therefore recommended that all entire Ecological Land Classification (ELC) ecosites polygons occupied by an extant subpopulation of Eastern Banded Tigersnails be prescribed as habitat in a habitat regulation.

The habitat in which the species is found has substantial leaf litter, decaying logs, and humus-rich soil, all of which provide moist microhabitat sites for hibernation, aestivation and egg-laying. A buffer around the ELC ecosite polygon will help maintain the important microhabitat properties required by the Eastern Banded Tigersnail. Therefore, it is further recommended that a buffer of 50 m be added to the ELC ecosite polygons to account for the dispersal of snails into neighbouring habitat, to reduce edge effects and to maintain important microhabitat properties. Without an understanding of how Eastern Banded Tigersnails use different habitat patches at different times of year, the importance of neighbouring habitat remains unclear. A 50 m buffer of suitable habitat around the ELC ecosites polygons takes into account the furthest net dispersal distance measured (32 m) in similar-sized terrestrial snail species (Edworthy et al. 2012), and ensures the protection of habitat that may be used by snails at different times of year. Habitat known to be unsuitable for Eastern Banded Tigersnails (e.g., roads and lakes) should be excluded from this buffer. Farmland is in general unsuitable habitat for the snail, and agricultural effluents and herbicides have been shown to alter snail population dynamics by affecting reproduction (Druart et al. 2011) and increasing mortality (Koprivnikar and Walker 2011). Transforming farmland into a filtering buffer by planting hedgerows, grass strips and poly-cultures (multiple plant species) with no chemical inputs around the ELC ecosite polygon could help reduce the impacts of effluents and herbicides on Eastern Banded Tigersnails.

Information on the spatial limits of habitat used by Eastern Banded Tigersnails is lacking. When new information on home range size, dispersal ability and key habitat features critical for supporting the species’ lifecycle becomes available, the area prescribed as habitat should be revised and updated.

Glossary

- Aestivation

- A period of deep and prolonged sleep, or torpor, that occurs in the summer or dry season in response to heat and drought.

- Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC)

- The committee established under section 14 of the Species at Risk Act that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Canada.

- Committee on the Status of Species at Risk in Ontario (COSSARO)

- The committee established under section 3 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Ontario.

- Conservation status rank

- A rank assigned to a species or ecological community that conveys its degree of rarity at the global (G), national (N) or subnational (S) level. These ranks, termed G-rank, N-rank and S-rank, are not legal designations. Global and National ranks are determined by NatureServe. Subnational S-ranks are determined for Ontario by the Natural Heritage Information Centre. The conservation status of a species or ecosystem is ranked from 1 to 5, preceded by the letter G, N or S which shows the geographic scale of the assessment. The numbers mean the following:

1 = critically imperilled

2 = imperilled

3 = vulnerable

4 = apparently secure

5 = secure

NR = not yet ranked - Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA)

- The provincial legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Ontario.

- Species at Risk Act (SARA)

- The federal legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Canada. This act establishes Schedule 1 as the legal list of wildlife species at risk. Schedules 2 and 3 contain lists of species that at the time the Act came into force needed to be reassessed. After species on Schedule 2 and 3 are reassessed and found to be at risk, they undergo the SARA listing process to be included in Schedule 1.

- Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) List

- The regulation made under section 7 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that provides the official status classification of species at risk in Ontario. This list was first published in 2004 as a policy and became a regulation in 2008.

List of abbreviations

- COSEWIC

- Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada

- COSSARO

- Committee on the Status of Species at Risk in Ontario

- ELC

- Ecological Land Classification

- ERCA

- Essex Region Conservation Authority

- ESA

- Ontario’s Endangered Species Act, 2007

- ISBN

- International Standard Book Number

- MECP

- Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks

- NCC

- Nature Conservancy of Canada

- SARA

- Canada’s Species at Risk Act

- SARO List

- Species at Risk in Ontario List

References

Ahlstrom, E.H. 1930. Mollusks collected in Bass Island region, Lake Erie. Nautilus 44:44-48.

Ansart, A., and P. Vernon. 2003. Cold hardiness in molluscs. Acta Oecologica 24:95-102.

Augspurger, C.K. 2013. Reconstructing patterns of temperature, phenology, and frost damage over 124 years: spring damage risk is increasing. Ecology 94:41-50.

Barker, G.M. 2001. The Biology of Terrestrial Molluscs. CABI Publishing, New York. 558 pp.

Baur, A., and B. Baur. 1990a. Are roads barriers to dispersal in the land snail Arianta arbustorum? Canadian Journal of Zoology 68:613-617.

Bellido, A. 1987. Field Experiment about direct effect of a heathland prescribed fire on microarthropod community. Revue d’Ecologie et de Biologie du Sol 24:603-633.

Blinn, W.C. 1963. Ecology of the land snails Mesodon thyroidus and Allogona profunda. Ecology 44:498-505.

Boutin, C., T. Dobbie, D. Carpenter, and C.E. Hebert. 2011. Effects of Double-crested Cormorants (Phalacrocorax auritus Less.) on island vegetation, seedbank, and soil chemistry: Evaluating island restoration potential. Restoration Ecology 19(6):720-727.

Burch, J.B., and T.A. Pearce. 1990. Terrestrial gastropods. Pp. 201-309, in D. L. Dindal (ed.). Soil Biology Guide. John Wiley and Sons, New York.

Campbell, S.P., J.L. Frair, J.P. Gibbs and R. Rundell, 2014. Coexistence of the endangered, endemic Chittenango Ovate Amber Snail (Novisuccinea chittenangoensis) and a non-native competitor. Biological Invasions 17(2):711-723.

Catling, P.M., G. Mitrow, and A. Ward. 2015. Major invasive alien plants of natural habitats in Canada. 12. Garlic Mustard, Alliaire officinale: Alliaria petiolata (M. Bieberstein) Cavara & Grande. CBA/ABC Bulletin 48(2):51-60.

CESCC (Canadian Endangered Species Conservation Council). 2016. Wild Species 2015: The General Status of Species in Canada. National General Status Working Group: 128 pp.

Clapp, G.H. 1916. Notes on the land shells of the islands at the western end of Lake Erie and description of new varieties. Annals of the Carnegie Museum 10:532-540.

COSEWIC. 2017. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Eastern Banded Tigersnail Anguispira kochi kochi and the Western Banded Tigersnail Anguispira kochi occidentalis in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. xv + 82 pp.

Dobbie, T., and J. Kehoe. 2008. Point Pelee National Park of Canada. Middle Island Conservation Plan 2008-2012. Parks Canada, Leamington, Ontario. 44 pp.

Drouin, M., R. Bradley, and L. Lapointe. 2016. Linkage between exotic earthworms, understory vegetation and soil properties in sugar maple forests. Forest Ecology and Management 364:113-121.

Druart, C., M. Millet, R. Scheifler, O. Delhomme, and A. de Vaufleury. 2011. Glyphosate and glufosinate-based herbicides: fate in soil, transfer to, and effects on land snails. Journal of Soil Sediments 11:1373-1384.

Edworthy, A.B., K.M.M. Steensma, H.M. Zandberg, and P.L. Lilley. 2012. Dispersal, home-range size, and habitat use of an endangered land snail, the Oregon forestsnail (Allogona townsendiana). Canadian Journal of Zoology 90(7):875-884.

Forsyth, R.G., P. Catling, B. Kostiuk, S. McKay-Kuja, A. Kuja. 2016. Pre-settlement Snail Fauna on the Sandbanks Baymouth Bar, Lake Ontario, Compared with Nearby Contemporary Faunas. Canadian Field-Naturalist 130(2):152-157.

Goodrich, C. 1916. A trip to the islands in Lake Erie. Annals of the Carnegie Museum 10:527-531.

Grimm, F.W., R.G. Forsyth, F.W. Schueler, and A. Karstad. 2010. Identifying Land Snails and Slugs in Canada: Introduced Species and Native Genera. Canadian Food Inspection Agency, Ottawa, Ontario. 168 pp.

Guillaumet, A., B.S. Dorr, G. Wang, and T.J. Doyle. 2014. The cumulative effects of management on the population dynamics of the Double-crested Cormorant Phalacrocorax auritus in the Great Lakes. IBIS 156:141-152.

Hotopp, K.P. 2002. Land snails and soil calcium in central Appalachian mountain forest. Southeastern Naturalist 1(1):27-44.

Hubricht, L. 1985. The distributions of the native land mollusks of the Eastern United States. Fieldiana Zoology 24:47-171.

Kawakami, K., S. Wada, and S. Chiba. 2008. Possible dispersal of land snails by birds. Ornithological Science 7:167–171.

Kimura, K., and S. Chiba. 2010. Interspecific interference competition alters habitat use patterns in two species of land snails. Evolutionary Ecology 24:815-825.

Knapp, E.E., B.L. Estes, and C.N. Skinner. 2009. Ecological effects of prescribed fire season: A literature review and synthesis for managers. USDA General Technical Report. Albany, California. 80 pp.

Koprivnikar, J., and P.A. Walker. 2011. Effects of the herbicide Atrazine's metabolites on host snail mortality and production of trematode cercariae. Journal of Parasitology 97(5):822-827.

Meadows, D.W. 2002. The effects of roads and trails on movement of the Odgen Rocky Mountain snail (Oreohelix peripherica wasatchnesis). Western North American Naturalist 62:377-380.

NatureServe. 2018. NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life [web application]. Version 7.1. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available http://explorer.natureserve.org. (Accessed: November 5, 2018).

NCC (Nature Conservancy of Canada). 2008. Management Guidelines: Pelee Island Alvars. NCC – Southwestern Ontario Region, London, Ontario. 43 pp.

Nekola, J.C. 2002. Effects of fire management on the richness and abundance of central North American grassland land snail faunas. Animal Biodiversity and Conservation 25(2):53-66.

Nicolai, A., J. Filser, R. Lenz, C. Bertrand, and M. Charrier. 2011. Adjustment of metabolite composition in the haemolymph to seasonal variations in the land snail Helix pomatia. Journal of Comparative Physiology B 181:457-466.

Nicolai, A., P. Vernon, R. Lenz, J. Le Lannic, V. Briand, and M. Charrier. 2013. Well wrapped eggs: Effects of egg shell structure on heat resistance and hatchling mass in the invasive land snail Cornu aspersum. Journal of Experimental Zoology A 319:63-73.

Nicolai, A., and A. Ansart. 2017. Conservation at a slow pace: Terrestrial gastropods facing fast changing climate. Conservation Physiology 5(1):007, doi: 10.1093/conphys/cox007.

Norden, A.W. 2010. Invasive earthworms: a threat to eastern North American forest snails? Tentacle 18:29-30.

North – South Environmental Inc. 2004. Vegetation Communities and Significant Vascular Plant Species of Middle Island, Lake Erie. Research Report of Point Pelee National Park of Canada. 97 pp.

Ontario Parks. 2005. Fish Point and Lighthouse Point. Park Management Plan of Wheatley Provincial Park, Wheatley, Ontario. 27 pp.

Pearce, T.A. 1990. Spool and line technique for tracing field movements of terrestrial snails. Walkerana 4(12):307-316.

Pearce, T.A., and M.E. Paustian. 2013. Are temperate land snails susceptible to climate change through reduced altitudinal ranges? A Pennsylvania example. American Malacological Bulletin 31:213-224.

Pilsbry, H.A. 1948. Land Mollusca of North America (North of Mexico). Volume 2, Part 2. Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, Monograph 3:i-xlvii + 521-1113.

Qiu, J., and M.G. Turner. 2017. Effects of non-native Asian earthworm invasion on temperate forest and prairie soils in the Midwestern US. Biological Invasions 19:73-88.

Sandilands, A. 2005. Birds of Ontario. Birds of Ontario: Habitat Requirements, Limiting Factors, and Status. Volume 1. Nonpasserines: Waterfowl through Cranes. University of British Columbia Press. Vancouver, British Columbia. 365 pp.

Thorndyke, R., and T. Dobbie. 2013. Point Pelee National Park of Canada. Report on research and monitoring for year 5 (2012) of the Middle Island Conservation Plan. Parks Canada, Leamington, Ontario. 34 pp.

Vagvolgyi, J. 1975. Body size, aerial dispersal, and origin of pacific land snail fauna. Systematic Zoology 24:465-488.

Varrin, R., J. Bowman, and P.A. Gray. 2007. The known and potential effects of climate change on biodiversity in Ontario’s terrestrial ecosystems: Case studies and recommendations for adaptation. Climate Change Research Report CCRR-09. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry. Queen’s Printer for Ontario, Toronto. 47. 1379 pp.

Viard, B., F. Pihan, S. Promeyrat, and S.J-C. Pihan. 2004. Integrated assessment of heavy metal (Pb, Zn, Cd) highway pollution: bioaccumulation in soil, Graminaceae and land snails. Chemosphere 55:1349-1359.

Wäreborn, I. 1979. Reproduction of two species of land snails in relation to calcium salts in the foerna layer. Malacologia 18:177-180.

Whitson, M. 2005. Cepaea nemoralis (Gastropoda, Helicidae): The invited invader. Journal of the Kentucky Academy of Science 66:82-88.

Wirth, T., P. Oggier, and B. Baur. 1999. Effect of road width on dispersal and population genetic structure in the land snail Helicella itala. Journal of Nature Conservation 8:23-29.

Personal communications

Forsyth, R.G. 2017-2018. Meetings with A. Nicolai. August-September 2017 and 2018. Taxonomist. Research Associate. New Brunswick Museum, St. John, New Brunswick.

Horrigan, E. 2018. Email correspondence to A. Nicolai. September 2018. Ecologist. Prescribed Burn Project Manager. Ontario Nature, Toronto, Ontario.