Four-leaved Milkweed Recovery Strategy

This document advises the ministry on ways to ensure healthy numbers of the four-leaved milkweed, a threatened or endangered species, return to Ontario.

Photo: Sean Blaney, Atlantic Canada Conservation Data Centre

About the Ontario Recovery Strategy Series

This series presents the collection of recovery strategies that are prepared or adopted as advice to the Province of Ontario on the recommended approach to recover species at risk. The Province ensures the preparation of recovery strategies to meet its commitments to recover species at risk under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) and the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk in Canada.

What is recovery?

Recovery of species at risk is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened, or extirpated species is arrested or reversed, and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of a species' persistence in the wild.

What is a recovery strategy?

Under the ESA, a recovery strategy provides the best available scientific knowledge on what is required to achieve recovery of a species. A recovery strategy outlines the habitat needs and the threats to the survival and recovery of the species. It also makes recommendations on the objectives for protection and recovery, the approaches to achieve those objectives, and the area that should be considered in the development of a habitat regulation. Sections 11 to 15 of the ESA outline the required content and timelines for developing recovery strategies published in this series.

Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for endangered and threatened species within one or two years respectively of the species being added to the Species at Risk in Ontario list. There is a transition period of five years (until June 30, 2013) to develop recovery strategies for those species listed as endangered or threatened in the schedules of the ESA. Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for extirpated species only if reintroduction is considered feasible.

What’s next?

Nine months after the completion of a recovery strategy a government response statement will be published which summarizes the actions that the Government of Ontario intends to take in response to the strategy. The implementation of recovery strategies depends on the continued cooperation and actions of government agencies, individuals, communities, land users, and conservationists.

For more information

To learn more about species at risk recovery in Ontario, please visit the Ministry of Natural Resources Species at Risk webpage.

Recommended citation

Poisson, G., K. Ursic, and M. Ursic. 2011. Recovery Strategy for Four–leaved Milkweed (Asclepias quadrifolia) in Ontario. Ontario Recovery Strategy Series. Prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Peterborough, Ontario. vi + 21 pp.

Cover illustration: Sean Blaney, Four–leaved Milkweed (Asclepias quadrifolia) at McMahon Bluff site, Prince Edward County, Ontario.

© Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2011

ISBN 978–1–4435–6781–7 (PDF)

Content (excluding the cover illustration) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source.

Cette publication hautement spécialisée Recovery strategies prepared under the Endangered Species Act, 2007, n'est disponible qu'en anglais en vertu du Règlement 411/97 qui en exempte l'application de la Loi sur les services en français. Pour obtenir de l'aide en français, veuillez communiquer avec Cathy Darevic au ministère des Richesses naturelles au 705–755–5580.

Authors

Geri Poisson, Beacon Environmental Ken Ursic, Beacon Environmental Margot Ursic, Beacon Environmental

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Sean Blaney, John Blaney and Tim Trustham for providing information on eastern Ontario populations and Albert Garofalo, Mary Gartshore, Deanna Lindblad and Tom Staton for information on potential habitat in the Niagara area. In addition, the authors would like to thank the many individuals who provided review and technical expertise to assist the development of the recovery strategy for this species.

Declaration

The recovery strategy for Four–leaved Milkweed was prepared in accordance with the requirements of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA). This recovery strategy has been prepared as advice to the Government of Ontario, other responsible jurisdictions and the many different constituencies that may be involved in recovering the species.

The recovery strategy does not necessarily represent the views of all of the individuals who provided advice or contributed to its preparation, or the official positions of the organizations with which the individuals are associated.

The goals, objectives and recovery approaches identified in the strategy are based on the best available knowledge and are subject to revision as new information becomes available. Implementation of this strategy is subject to appropriations, priorities and budgetary constraints of the participating jurisdictions and organizations.

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this strategy.

Responsible jurisdictions

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources

Executive summary

Four–leaved Milkweed (Asclepias quadrifolia) is a perennial herb of woodlands and forest edges that grows up to 80 centimetres in height. Leaf arrangement is in opposite pairs, with each pair separated by a short internode, giving the appearance of being whorled. In southern Ontario, maturity is attained between 5 to 10 years and reproduction is sexual. The species flowers from late May until the end of June. Pollination is mostly by bees (Bombus spp.) and butterflies (Lepidoptera). Tufted seeds develop in a pod that matures over the summer. Seed dispersal is by wind. Populations consist of scattered individuals or groups.

In Ontario, populations of Four–leaved Milkweed have been recorded from only two localities: the Bay of Quinte region along the north shore of Lake Ontario and the Niagara River Gorge connecting Lake Erie and Lake Ontario. Populations at these localities, as well as those found in New York, Vermont and New Hampshire, are at the northern limit of the species range in North America. At present, it is believed that there are only two extant populations remaining in Ontario. Both of these populations are situated in Prince Edward County in the Bay of Quinte region. Historically, Four–leaved Milkweed populations have also been recorded from the neighbouring Lennox and Addington County of the Bay of Quinte region as well as from the Niagara River Gorge.

Four–leaved Milkweed occurs in a provincially rare habitat type (Bur Oak – Shagbark Hickory Woodland on shallow soil over limestone) and there are fewer than 200 known mature individuals. This species was assessed as endangered by the Committee on the Status of Species at Risk in Ontario (COSSARO) and designated under the Endangered Species Act, 2007. At the federal level, this species was assessed as endangered by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC).

Major threats to conservation of the remaining populations of Four–leaved Milkweed in Ontario include:

- habitat loss due to residential and agriculture land uses;

- habitat loss and degradation due to woody species succession and invasive species; and

- impacts from anthropogenic activities such as hiking and all terrain vehicle use.

The long–term recovery goal for Four–leaved Milkweed is to protect extant populations and re–establish new populations in appropriate habitat where feasible.

Specific objectives are listed below in priority sequence as follows.

- Identify and protect extant populations and associated habitat through public ownership or conservation easement.

- Prioritize and implement necessary research activities to gather required information for effective species recovery.

- Implement a standardized long–term monitoring program to assess the status of extant populations.

- Confirm known and potential threats to extant populations.

- Develop and implement site specific best management practices to address known and potential threats

- Investigate the feasibility of reintroduction at current and historic sites and other suitable habitat.

- Develop a communication and outreach strategy.

The approaches to recovery emphasize the protection of existing populations and their habitat, monitoring existing populations to identify and mitigate threats through management, conservation of the genetic pool through gene banking, and plant propagation and re–introduction at extant sites and/or suitable new sites, where deemed feasible.

It is recommended that the minimum area that should be considered in developing a habitat regulation for Four–leaved Milkweed include the area occupied by all extant populations and the surrounding extent of the vegetation community type (based on Ecological Land Classification for southern Ontario) in which it occurs. This will allow for future growth, expansion and migration of these populations. The habitat regulation should be subject to revision as more information on the species' ecology, habitat requirements and its pollinators' habitat requirements becomes available.

1.0 Background information

1.1 Species assessment and classification

Common name: Four–leaved Milkweed

Scientific name: Asclepias quadrifolia

SARO List Classification: Endangered

SARO List History: Endangered (2010)

COSEWIC Assessment History: Endangered (2010)

SARA Schedule: No Schedule, No Status

Conservation status rankings:

GRANK: G5 NRANK: N1 SRANK: S1

The glossary provides definitions for the abbreviations above.

1.2 Species description and biology

Species description

Four–leaved Milkweed (Asclepias quadrifolia) is an erect, herbaceous, perennial, woodland plant and one of the smallest in the Milkweed (Asclepiadaceae) family. It typically grows a single, unbranched stem from 20 to 80 cm tall (Chaplin and Walker 1982, Gleason and Cronquist 1991). Leaf arrangement is in opposite pairs with two pairs separated by a short internode, giving the appearance of being in a whorl of four. Flowers are arranged terminally in one to four umbels, each containing 5 to 25 small, pinkish–white flowers (Chaplin and Walker 1982, Cabin et al. 1991). Seeds are borne in a pod, usually with 20 to 35 brown, flattened, teardrop–shaped seeds per pod (Chaplin and Walker 1982). To aid in dispersal, the seeds have dense tufts of long, silky white hairs at the top. Mature plants produce one or two, rarely three, pods per plant.

Species biology

Four–leaved Milkweed reproduces only from seed (Chaplin and Walker 1982). No references could be found documenting seed longevity for this species however; one study suggests that seeds of Showy Milkweed (A. speciosa) do not remain dormant in the soil for more than two years (Chepil 1946). Comes et al. (1978) found that Showy Milkweed seeds had a 71% germination rate after five years of dry storage. Four– leaved Milkweed plants are slow growing, reaching 13.5 cm in height after three years, with most of the annual growth occurring in the spring before the tree canopy closes (Chaplin and Walker 1982). Chaplin and Walker (1982) also found that Four–leaved Milkweed is relatively slow to mature, estimating that plants do not produce seed until at least from 5 to 10 years depending on resources such as soil depth, moisture and sunlight. Flowering, in Missouri, occurs from late May through mid–June (Chaplin and Walker 1982). In Ontario, Four–leaved Milkweed is known to flower at least until the end of June (G. Poisson pers. obs. 2006). It should be noted that much of the available ecology, growth and maturation information is from studies in Missouri. Populations occurring near the northern extent of its range (i.e., Ontario) may have slightly different characteristics. Pollination is a complex, insect–mediated process. Chapman and Walker (1982) found 22 species of insects carrying pollinaria, virtually all of which were species of Hymenoptera (bees and wasps) measuring between 8 to 12 mm in body length and Lepidoptera (butterflies, moths and skippers) 12 to 20 mm in length.

Although many insects are attracted to the copious amounts of nectar produced by the flowers, not all are effective pollinators. The smaller individuals lack the strength to remove pollinaria that become attached to their legs, and the larger ones grasp the flowers from below while feeding. Of the six major potential pollinators identified by Chapman and Walker (1982) in Missouri, the main species was a bee, Melissodes desponsa Smith (Hymenoptera). The five other major species were skippers [family Hesperiidae – Zabulon Skipper (Poanes zabulon), Hobomok Skipper (Poanes hobomok), Tawny–edged Skipper (Polites Themistocles) and Peck’s Skipper (Polites coras/P. peckius)] and a Nymphalid butterfly – Pearl Crescent (Phyciodes tharos). All of the above species, with the exception of Zabulon Skipper, occur in Ontario within the Four–leaved Milkweed range. Other species of bees and butterflies are known pollinators of a similar species of milkweed, Poke Milkweed (A. exaltata), and may also be important for Four–leaved Milkweed (Queller 1985, Broyles and Wyatt 1994). Pollen dispersal in Poke Milkweed can be over distances as great as one kilometre (Wyatt and Broyles 1994), but is usually much shorter. Seed pods mature in the fall and release their tufted seeds. Morse and Schmitt (1985) found that seed dispersal in Common Milkweed (A. syriaca) can be over 150 m. Four–leaved Milkweed average seed dispersal distance is likely less than that of Common Milkweed; Four–leaved Milkweed is shorter and is found in a forested habitat with less wind speed and more obstacles.

1.3 Distribution, abundance and population trends

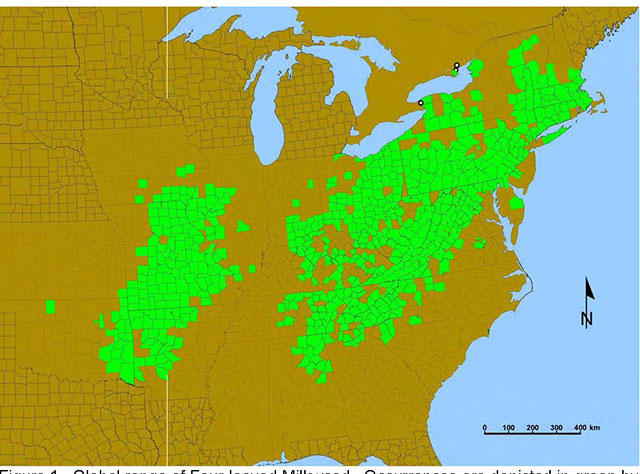

Global range

Four–leaved Milkweed is native to eastern North America where it occurs in two disjunct regions separated by the Mississippi River Valley (Figure 1). The western region extends from eastern Oklahoma and western Arkansas northward through Missouri, extreme southeast Kansas, western Illinois, eastern Iowa and Minnesota. The eastern region extends from the northern parts of Alabama, Georgia and South Carolina in the Appalachian Mountains north to eastern Indiana, along the south of Lake Erie and Lake Ontario in Ohio, Pennsylvania and New York, to the Champlain Valley of New York and Vermont and to southern New Hampshire. In Canada, Four–leaved Milkweed has been recorded from the Bay of Quinte region along the north shore of Lake Ontario and the Niagara River gorge linking Lake Erie to Lake Ontario.

Figure 1. Global range of Four–leaved Milkweed

Occurrences are depicted in green by county, with Canadian historical occurrences indicated by dots. (COSEWIC 2010, modified from Kartesz 2008).

Enlarge Figure 1. Global range of Four–leaved Milkweed

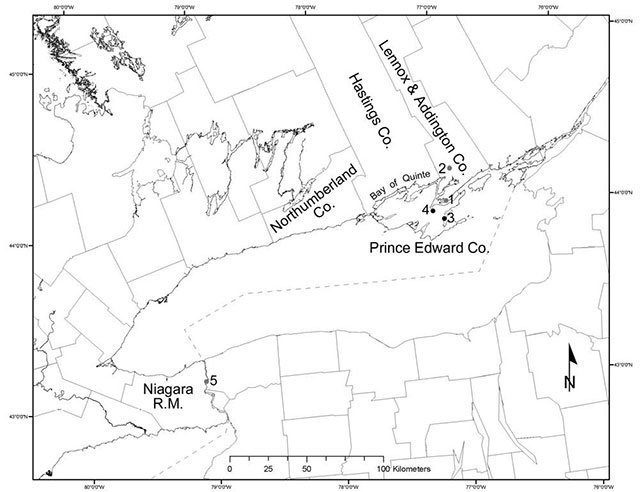

Canadian Range

In Canada, Four–leaved Milkweed is only known to occur in the province of Ontario where populations have been recorded from two localities; the Bay of Quinte region along the north shore of Lake Ontario and the Niagara River Gorge connecting Lake Erie and Lake Ontario (Argus et al. 1982–1987). The locations of extant and historic populations of Four–leaved Milkweed in Canada are illustrated in Figure 2.

At present, it is believed that there are only two extant populations remaining in Ontario. Both of these populations are situated in Prince Edward County in the Bay of Quinte region. The McMahon Bluff population (Figure 2: Site 3) was identified in 2006 by Sean Blaney. The Macaulay Mountain Conservation Area population (Figure 2: Site 4) was identified in 2007 by David Bree. This population is situated 9.0 km from the McMahon Bluff population.

Historically, Four–leaved Milkweed populations have also been recorded from the neighbouring Lennox and Addington County of the Bay of Quinte region as well as from the Niagara River Gorge. John Macoun (1883–1890) cites an 1868 collection record from "Bay of Quinte" (Figure 2: Site 1) as well as an 1890 record from Adolphustown and "near Napanee" in Lennox and Addington County (Figure 2: Site 2). In the Niagara Region, populations were documented from the Niagara River Gorge, downstream of Niagara Falls, near Niagara Glen and Queenston, with the last record being in 1956 by Soper and Fleishmann. Despite extensive surveys for this species, none of the Niagara populations could be rediscovered.

Figure 2. Historical and current distribution of Four–leaved Milkweed in Ontario

Gray dots (1, 2, 5) are historic locations and black dots (3, 4) are extant locations (Source: COSEWIC 2010).

Enlarge Figure 2. Historical and current distribution of Four–leaved Milkweed in Ontario.

Abundance

The two extant populations were only recently discovered. It is possible that additional populations may be identified in the future. The McMahon Bluff population (Figure 2: Site 3) was surveyed in 2006 by C.S. Blaney, G. Poisson, T. Norris, M.J. Oldham and B. van Sleeuwen, in 2007 by D. Bree and in 2008 by C.S. Blaney and estimated to support 136 individuals scattered over an area of approximately 20 ha. The Macaulay Mountain Conservation Area population (Figure 2: Site 4) was surveyed by D. Bree in 2007, by M. J. Oldham and S. Brinker in 2008 and by T. Norris in 2010, and is estimated to support 42 individuals in an area of approximately 0.25 ha.

It is estimated that the total number of individuals of Four–leaved Milkweed present in the two extant Ontario populations, including a margin of error for uncounted, non– flowering stems, ranges between 158 plants and possibly up to 228, with at least 96 reproducing or flowering individuals (COSEWIC 2010). It is not possible to estimate population trends for the extant populations as there has been insufficient detailed monitoring to provide this information. Anecdotal evidence suggests that the McMahon Bluff population may be declining due to changes in habitat conditions (J. Blaney pers. comm. 2010).

There is insufficient information available in the historical record describing the size of extirpated populations from Lennox & Addington County and Niagara Region.

1.4 Habitat needs

Information relating to the habitat requirements for populations of Four–leaved Milkweed in Ontario is limited. Habitat descriptions from various sources (COSEWIC 2010, Poisson pers. obs. 2006, Cabin et al. 1991, Chaplin and Walker 1982) note that populations typically occur on dry to mesic, shallow or rocky soils over limestone or, sometimes sandstone, bedrock on or near steep slopes within a semi–open, mature deciduous forest, usually comprised of Oak and Hickory. Soil pH is, when reported, usually circumneutral (around 7) but can be slightly acidic to strongly basic.

There is slightly more habitat information available for populations of this species in the United States. A summary of habitat characteristics is presented in Table 1 using information obtained from a review of available literature and correspondence with researchers.

Table 1. Summary of habitat conditions for Four–leaved Milkweed in the United States.footnote 1

| State | Geographic Notes | Authority | Habitat / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Delaware | Piedmont Province of New Castle County | William McEvoy | Historic records only |

| Indiana | SE Indiana | Michael Homoya | Mostly on calcareous soils, although not necessarily associated with outcrops of limestone. Typically on steep, well drained forested slopes, mostly on calcareous soils. Chinquapin Oak (Quercus muehlenbergii) and White Oak are common among various canopy trees |

| Iowa | South–central & southeast Iowa | John Pearson | Dry to mesic, upland woods |

| Kansas | Restricted to Ozark Plateau physiographic province in extreme SE Kansas | Craig Freeman | Oak–hickory forest or woodlands on slopes with cherty, rocky soils mostly on dolomite or limestone but potentially on sandstone as well |

| Missouri | Tim Smith | Dry–mesic forest or woodlands on dolomite, typically where bedrock has weathered away leaving a chert–rich, somewhat acidic or circumneutral soil | |

| Missouri | University of Missouri, Columbia | Chaplin and Walker (1982) | Mature oak – hickory woods, soils thin and rocky overlying limestone; White Oak, with Shagbark Hickory, Sugar Maple and White Ash dominant |

| New York | New York herbarium label info supplied by Steve Young | Dry, open, often rocky woods (mention of rocky exposed ridge, rock ledges, above cliffs and on sandstone pavement) on limestone, shale or sandstone | |

| North Carolina | Mountain and Piedmont regions | Suzanne Mason, citing Weakley (2008) | Moist to dryish forests and forest margins, most common on mafic and calcareous substrates |

| Vermont | Champlain & Connecticut River valleys | Bob Popp, Botanist – Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department | Dry oak – hickory – hop–hornbeam (Ostrya virginiana) forest, mostly on calcareous areas in forest openings or near the edge of cliffs where it receives more light |

| Vermont | Shaw Mountain Preserve | Cabin et al. (1991) | Grassy meadows in mature, mixed deciduous forest over limestone; mid–size Sugar Maple, Shagbark Hickory, White Pine, White Oak and Hop–hornbeam (Ostrya virginiana) with low grasses and sedges. |

| Virginia | Shenandoah National Park, Virginia | Steve Broyles, State University of New York, Cortland | Often on shaded roadside embankments at margins of American Beech and Red Oak– dominated forest; historically dominated by American Chestnut |

In Ontario, the McMahon Bluff population is situated in a mature, open to semi–closed woodland community on shallow soils on a flat to gently sloped plateau near a steep limestone escarpment slope. Dominant tree species include Bur Oak (Quercus macrocarpa), Shagbark Hickory (Carya ovata) and Ironwood (Ostrya virginiana), with Eastern Red–Cedar (Juniperus virginiana), Chinquapin Oak (Quercus muhlenbergii), Sugar Maple (Acer saccharum), Basswood (Tilia americana), Bitternut Hickory (C. cordiformis) and White Ash as lesser associates. Dominant tall shrubs include Prickly– Ash (Zanthoxylem americanum), Gray Dogwood (Cornus racemosa) and Downy Arrow– wood (Viburnum rafinesquianum), and dominant low shrubs include Common Juniper (Juniperus communis), Snowberry (Symphoricarpos albus) and Fragrant Sumac (Rhus aromatica). The ground layer vegetation is composed of Woodland Sunflower (Helianthus divaricatus) and other abundant herbs including Blue–stemmed Goldenrod (Solidago caesia), Pennsylvania Sedge (Carex pensylvanica), Early Meadow–Rue (Thalictrum dioicum), Large–leaved Aster (Eurybia macrophylla) and Barren Strawberry (Waldsteinia fragarioides). Lesser associates include Blue Phlox (Phlox divaricata), Hairy Brome (Bromus pubescens), Seneca Snakeroot (Polygala senega) and Bastard Toadflax (Comandra umbellata) (COSEWIC 2010, G. Poisson pers. obs. 2006).

Using the Ecological Land Classification (ELC) system for southern Ontario (Lee et al. 1998), this woodland community may be described as either a Dry Bur Oak – Shagbark Hickory Tallgrass Woodland Type (TPW1–2), or a Shagbark Hickory – Prickly Ash Treed Alvar Type (ALT1–2). Currently, both of these community types are ranked as S1 (critically imperiled) by the Ontario Natural Heritage Information Centre.

The Macaulay Mountain Conservation Area is approximately 160 ha in size and was subjected to livestock grazing prior to protection as a conservation area in the 1970s. Habitat conditions include dry–fresh shallow soils on limestone bedrock. Vegetation consists primarily of regenerating Eastern Red–Cedar and cool season pasture grasses (T. Trustham pers. comm. 2010). Based on the site description provided, this community is likely best described as a Red Cedar Cultural Alvar Woodland Type (CUW2–1), using the ELC system for southern Ontario (Lee et al. 1998). However, the immediate area occupied by Four–leaved Milkweed is more like that described for the McMahon Bluff population, either a Dry Bur Oak – Shagbark Hickory Tallgrass Woodland Type (TPW1–2), or a Shagbark Hickory – Prickly Ash Treed Alvar Type (ALT1–2). Currently, both of these community types are ranked as S1 (critically imperiled) by the Ontario Natural Heritage Information Centre.

1.5 Limiting factors

There are a number of factors that can potentially limit the size and viability of populations of Four–leaved Milkweed in Ontario. Some of these factors are inherent to the species biology and ecology while others relate to environmental conditions and anthropogenic influences. Briefly some of these limiting factors are as follows.

- Plants reproduce only from seed, not vegetatively – This may mean the species is vulnerable to factors that limit sexual reproduction such as herbivory, late frosts, or lack of pollinators.

- Delayed maturation (from 5 to 10 years) – Plants may be vulnerable to loss before they can reproduce. This is based on studies in Missouri and may be different for Ontario populations.

- Pollinator dependency (mainly bees and butterflies) – Four–leaved Milkweed is not pollinated by wind or animals. Reductions in pollinator species could limit plant reproduction. Chaplin and Walker (1982) found that more than 50% of insects carrying pollinaria were of one species. Cabin et al. (1991) found very low rates of pollination.

- Some reliance on a disturbance regime of periodic fire to control woody shrub encroachment and maintain optimal growing conditions – Solar exposure may have an effect on plant energy production. Plants found growing at forest edges have been shown to be larger and produce more seeds than those growing in the forest interior (Chaplin and Walker 1982).

- Association with alvar–type habitats – Alvar–type habitats are naturally rare in Ontario and ranked as S1 (critically imperiled). As such, suitable habitat is very limited in the province.

- Extremely isolated, small populations – The two extant populations are separated by 9 km of unsuitable habitat. Seed and/or pollen dispersal between these two populations is highly unlikely and may result in lower genetic diversity and inbreeding depression.

- Lack of suitable habitat nearby that might be naturally colonized.

1.6 Threats to survival and recovery

A number of threats to this species have been identified, based on the ecological conditions and cultural activities observed at the two locations of extant populations. Known and potential threats are listed below.

- Habitat loss from potential changes in land use is a threat. The McMahon Bluff site is currently under private ownership and can potentially support land uses such as residential development or agriculture activities. There are presently no stewardship agreements in place to protect potentially suitable habitats adjacent to the existing population.

- Natural succession by woody vegetation such as Prickly Ash (Zanthoxyllum americanum), Gray Dogwood (Cornus racemosa) and Red Cedar (Juniperus virginiana), represents a known threat to populations of Four–leaved Milkweed. These species have the potential to rapidly colonize large areas of habitat occupied by Four–leaved Milkweed resulting in loss of habitat and extirpation of remaining populations.

- Invasive species, such as Common Buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica) and Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata) are known to occur in the vicinity of the extant populations but are not yet problematic. Dog–strangling Vine or European Swallow–wort (Cynanchum rossicum) is also found within several kilometers of the extant populations and represents a serious threat. These species have the potential to alter habitat conditions and displace populations of Four–leaved Milkweed through modification of light levels and soil conditions. Since invasive species are typically associated with anthropogenic disturbances, increases in human activities adjacent to the extant populations can potentially increase this threat.

- Anthropogenic activities such as hiking and all–terrain vehicle (ATV) use have been noted in the vicinity of the extant populations. These activities have the potential to impact populations of Four–leaved Milkweed through trampling, soil compaction and drainage alterations. This potential threat is considered low to moderate at both the Macaulay Mountain and McMahon Bluff sites. Presently, there are no existing trails immediately adjacent to the plants at either site.

These threats have not been assessed to determine the nature of their interactions with Four–leaved Milkweed. More information is needed to confirm that these factors are indeed threats to the species' survival, their relative severity and the underlying cause(s) of these threats (see Knowledge Gaps below).

1.7 Knowledge gaps

A review of the literature reveals that there is a paucity of information on Four–leaved Milkweed populations in Ontario. Additional research is necessary to fill in the knowledge gaps required to support this recovery strategy. This includes basic information needs such as an updated population census, detailed habitat characterization and mapping, and monitoring program. This basic information is necessary to support population viability analyses (PVA) and other conservation and management tools.

Key areas where knowledge gaps exist are as follows. Survey Requirements Complete and reliable census data for Four–leaved Milkweed populations is presently lacking mostly due to the relatively short time period since this species was rediscovered in Ontario. A standardized method of documenting numbers of plants, their attributes, habitat and populations is needed to provide reliable baseline data on which future recovery actions can be developed and assessed.

Species distribution

Through consultations with authorities and researchers, it was found that, despite recent search efforts, additional areas of potentially suitable habitat in Prince Edward County and the greater Bay of Quinte region remain to be investigated for the presence of Four– leaved Milkweed (S. Blaney pers. comm. 2010, T. Trustham pers. comm. 2010).

Further landscape analysis of potential habitat (i.e., alvar woodlands) should be initiated followed by a systematic survey program.

Habitat needs and Species Ecology

A detailed analysis should be conducted to better understand the specific habitat requirements of Four–leaved Milkweed. This will help inform the MNR in identifying areas for consideration in developing a habitat regulation. Areas of study should include, but not be limited to:

- classification of vegetation community types in and adjacent to extant populations using the ELC for southern Ontario;

- soil sampling and assessment to determine optimal soil conditions (e.g. depth, moisture, pH, nutrients);

- maturation rates, pollinators, pollination rates, pollen dispersal distances, incidences of fruit abortion, seed production rates, seed quality, energetic constraints and herbivory. Cabin et al. (1991) postulated that Four–leaved Milkweed may have lower seed quality at its northern range limit as well as lower pollination rates;

- experiments to establish seed dormancy periods, viability levels and propagation techniques;

- assessment of the relationship between this species and mycorrhizal associations;

- assessment of interactions with native and exotic herbs and shrubs (e.g., competition for light and other resources, allelopathy);

- plant’s ability to colonize successional habitats and which types;

- population viability assessment, effects of genetic isolation and minimum viable population level; and

- Limiting factors such as tolerance limits (light, pH, disturbance type and intensity), setback requirements.

1.8 Recovery actions completed or underway

Informal surveys have occurred at the McMahon Bluff to monitor the Four–leaved Milkweed population in 2006, 2007 and fall of 2008. The Macaulay Mountain population was visited upon initial discovery in 2007 and again in 2008 and 2010. No formal program has been initiated at either site to inventory, monitor or assess this species, its habitat or threats.

For several years, the Hastings Prince Edward Land Trust has been actively campaigning and fundraising to purchase the McMahon Bluff property. However, the property was recently sold and is held by a private landowner. Efforts to ensure the long–term protection of the habitat for Four–leaved Milkweed on this property are ongoing.

The Quinte Conservation Authority owns the Macaulay Mountain Conservation Area where the second, smaller population of Four–leaved Milkweed exists. Presently there is no formal management plan for the long–term protection and management of this species and its habitat. The management regime has been to allow the area to naturalize. However, priority management actions on this property are to improve and expand fencing (T. Trustham pers. comm. 2010). This would help to prevent access by recreational motorized vehicles and the further development of unofficial trails.

2.0 Recovery

2.1 Recovery goal

The long–term recovery goal for Four–leaved Milkweed is to protect extant populations and re–establish new populations in appropriate habitat where feasible.

2.2 Protection and recovery objectives

The recovery objectives for Four–leaved Milkweed place the most emphasis on ensuring the long–term protection of extant populations and their habitat. A list of protection and recovery objectives are provided in Table 2.

Table 2. Protection and recovery objectives

| No. | Protection or Recovery Objective |

|---|---|

| 1 | Identify and protect extant populations and associated habitat through public ownership or conservation easement. |

| 2 | Prioritize and implement necessary research activities to gather required information for effective species recovery. |

| 3 | Implement a standardized long–term monitoring program to assess the status of extant populations. |

| 4 | Confirm known and potential threats to extant populations. |

| 5 | Develop and implement site specific best management practices to address known and potential threats |

| 6 | Investigate the feasibility of reintroduction at current and historic sites and other suitable habitat. |

| 7 | Develop a communication and outreach strategy. |

2.3 Approaches to recovery

Table 3. Approaches to recovery of Four–leaved Milkweed in Ontario

1. Identify and protect extant populations and associated habitat

| Relative Priority | Relative Timeframe | Recovery Theme | Approach to Recovery | Threats or Knowledge Gaps Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Short–term | Protection, Stewardship | 1.1 Habitat protection

|

|

| Beneficial | Short–term | Inventory, Monitoring and Assessment Protection | 1.2 Conduct further searches of suitable habitat for undiscovered populations in the region of extant and historical occurrences |

|

2. Prioritize and implement necessary research activities to gather required information for effective species recovery

| Relative Priority | Relative Timeframe | Recovery Theme | Approach to Recovery | Threats or Knowledge Gaps Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Long–term | Research | 2.1 Prioritize and undertake research to address remaining questions regarding the species' ecology:

|

|

| Critical | Short–term | Protection | 2.2 Identify areas required to protect extant populations

|

|

3. Implement a standardized long–term monitoring program to assess the status of extant populations

| Relative Priority | Relative Timeframe | Recovery Theme | Approach to Recovery | Threats or Knowledge Gaps Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | On–going | Management Inventory, Monitoring and Assessment | 3.1 Population census –

|

|

| Necessary | On–going | Management Inventory, Monitoring and Assessment | 3.2 Habitat monitoring –

|

|

4. Confirm known and potential threats to extant populations

| Relative Priority | Relative Timeframe | Recovery Theme | Approach to Recovery | Threats or Knowledge Gaps Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Long–term | Communications Management Inventory, Monitoring and Assessment Research Stewardship | 4.1 Form a team to co–ordinate actions from land managers, landowners, conservation groups, researchers and government to

|

|

5. Develop and implement site specific best management practices to address known and potential threats

| Relative Priority | Relative Timeframe | Recovery Theme | Approach to Recovery | Threats or Knowledge Gaps Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Necessary | Long–term | Communications Management Inventory, Monitoring and Assessment Research Stewardship | 5.1 Form a team to co–ordinate actions from land managers, landowners, conservation groups, researchers and government to prioritize, reduce and mitigate threats –

|

|

| Necessary | Short–term | Protection Stewardship Management | 5.2 Management on public lands

|

|

6. Investigate the feasibility of reintroduction at current and historic sites and other suitable habitat

| Relative Priority | Relative Timeframe | Recovery Theme | Approach to Recovery | Threats or Knowledge Gaps Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beneficial | Long–term | Management Inventory, Monitoring and Assessment | 6.1 Undertake a landscape level scoping of potential sites for re–introduction

|

|

| Beneficial | Long–term | Management Research | 6.2 Undertake a seed collection program for gene conservation and to support a reintroduction program.

|

|

8. Develop a communication and outreach strategy

| Relative Priority | Relative Timeframe | Recovery Theme | Approach to Recovery | Threats or Knowledge Gaps Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beneficial | Long–term | Management Education and Outreach Stewardship | 7.1 Using appropriate partnerships, develop a communication and outreach strategy that identifies effective techniques for enlisting landowner and public support, implementing the strategy and evaluating its success periodically

|

|

Narrative to Support Approaches to Recovery

Population enhancement and site restoration at the two known Four–leaved Milkweed populations is currently considered necessary. Although both are regarded as naturally occurring, the number of populations is extremely limited and long–term threats have been identified. Of the two Ontario populations, one may be declining (J. Blaney pers. comm. 2010).

It is not known whether the current number of plants at the two Ontario populations will be sufficient to permit Four–leaved Milkweed’s long–term viability (see Knowledge Gaps). However, until further information is available on minimum viable population size, the priority for recovery of Four–leaved Milkweed is to protect and monitor extant sites.

Although historically, this species was not widespread in Ontario, it has been presumed extirpated in several locations, most notably in the Niagara area. Re–establishment in historic locations may aid the recovery of Four–leaved Milkweed to historic population levels and ensure its long–term survival.

2.4 Performance measures

The success of recovery efforts can be measured through ongoing monitoring of populations and threats, assessment of habitat conditions and evaluating the status and progress of the specified research, management, stewardship and education programs (Table 4). Performance measures should be based on the extent to which goals and objectives have been met.

Table 4. Performance measures for the recovery of Four–leaved Milkweed

| Objective | Performance Measure |

|---|---|

| 1. Identify and protect extant populations and associated habitat through public ownership or conservation easement | Population extent and habitat features, including ELC communities, delineated for all populations (short–term, i.e., within 5 years) All habitat protected under the ESA and/or through land acquisition (short–term) |

| 2. Prioritize and implement necessary research activities to gather required information for effective species recovery. | Source funding secured for specified research programs (short–term) Information gathered regarding species and population biology, ecology and habitat requirements (short–term) Gene conservation measures implemented (long–term) |

| 3. Implement a standardized long–term monitoring program to assess the status of extant populations. | Standardized inventory techniques developed (short–term) Population census conducted at all sites periodically (short–term) Habitat of extant populations monitored annually (short–term) |

| 4. Confirm known and potential threats to extant populations. | Threats and their extent and severity are identified and prioritized (short–term). |

| 5. Develop and implement a management strategy to address known and potential threats. | Approaches for managing Four–leaved Milkweed habitat and mitigating threats developed (short–term) Threats mitigated as necessary to achieve recovery goal (long–term) |

| 6. Investigate the feasibility of reintroduction at current and historic sites and other suitable habitat. | Seed collection and propagation program initiated (short–term) Recovery potential of historic and potential sites investigated(long–term) |

| 7. Develop a communication and outreach strategy | Appropriate partners have contributed to the development of a communication and outreach strategy that identifies an implementation strategy and periodic evaluation (short–term) Implementation of strategy resulting in the identification and implementation of effective techniques for enlisting landowner and public support (i.e., information pamphlet) (long–term) |

2.5 Area for consideration in developing a habitat regulation

Under the ESA, a recovery strategy must include a recommendation to the Minister of Natural Resources on the area that should be considered in developing a habitat regulation. A habitat regulation is a legal instrument that prescribes an area that will be protected as the habitat of the species. The recommendation provided below by the authors will be one of many sources considered by the Minister when developing the habitat regulation for this species.

It is recommended that the minimum area that should be considered in developing a habitat regulation for Four–leaved Milkweed include the area occupied by all extant populations and the surrounding extent of the vegetation community type (based on the ELC for southern Ontario) in which it occurs. This would allow for future growth, expansion and migration of these populations. The habitat regulation should be subject to revision as more information on the species' ecology, habitat requirements and its pollinators' habitat requirements becomes available. This approach is consistent with provincial habitat mapping guidelines for the Conservation Land Tax Incentive Program (Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources 1998). Known ELC for extant sites are described in Section 1.4. These boundaries should be refined as more information is gained on the factors that may influence habitat suitability and quality.

In Ontario, the current occupied habitats are restricted to the Quinte Region in the south–eastern part of the province. However, historical records for Ontario indicate that, Four–leaved Milkweed was known to occur in the Niagara Region and the Quinte Region. Consequently, potential habitats, after further study, may include historical locations within the species' range as well.

Habitat that is not currently occupied by the species, or not currently known to be occupied, may also be required for recovery of the species. Before suitable habitat for reintroduction can be identified (including historic sites), further research is necessary to define optimum habitat attributes. Potential recovery areas would include sites within the species' range that exhibit many of the key habitat attributes listed in Section 1.4. In addition, given the plant’s potential sensitivity to trampling and ATV use, it would be advisable to select locations where these activities are restricted.

Glossary

Cherty: A soil whose origin is a hard, dense sedimentary rock composed of fine–grained silica.

Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC): The committee responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Canada.

Committee on the Status of Species at Risk in Ontario (COSSARO): The committee established under section 3 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Ontario.

Conservation status rank: A rank assigned to a species or ecological community that primarily conveys the degree of rarity of the species or community at the global (G), national (N) or sub national (S) level. These ranks, termed G–rank, N–rank and S–rank, are not legal designations. The conservation status of a species or ecosystem is designated by a number from 1 to 5, preceded by the letter G, N or S reflecting the appropriate geographic scale of the assessment. The numbers mean the following:

- = critically imperiled

- = imperiled

- = vulnerable

- = apparently secure

- = secure

Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA): The provincial legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Ontario.

Species at Risk Act (SARA): The federal legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Canada. This Act establishes Schedule 1 as the legal list of wildlife species at risk to which the SARA provisions apply. Schedules 2 and 3 contain lists of species that at the time the Act came into force needed to be reassessed. After species on Schedule 2 and 3 are reassessed and found to be at risk, they undergo the SARA listing process to be included in Schedule 1.

Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) List: The regulation made under section 7 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that provides the official status classification of species at risk in Ontario. This list was first published in 2004 as a policy and became a regulation in 2008.

Umbel: A flower cluster in which the individual flower stalks emerge from the same point on the stem.

References

Argus, G.W., C.J. Keddy, K.M. Pryor and D.J. White. 1982–1987. Atlas of the Rare Vascular Plants of Ontario, G.W. Argus & D.J. White (eds.). National Museum of Natural Sciences, Botany Division, Ottawa, Ont.

Blaney, J. 2010. Personal Communication. Email correspondence with John Blaney. December 2010. Secretary, Hastings–Prince Edward Land Trust, Belleville, ON.

Blaney, S. 2010. Personal Communication. Email correspondence with Sean Blaney. December 2010. Botanist / Assistant Director, Atlantic Canada Conservation Data Centre, Sackville, NB.

Cabin, R. J., J. Ramstetter and R. E. Engel. 1991. Reproductive limitations of a locally rare Asclepias. Rhodora 93(873): 1–10.

Chaplin, S.J. and J.L. Walker. 1982. Energetic Constraints and Adaptive Significance of the Floral Display of a Forest Milkweed. Ecology 63: 1857–1870.

Chepil, W.S. 1946. Germination of seeds. I. Longevity, periodicity of germination, and vitality of seeds in cultivated soil. Scientific Agriculture. 26: 307–346.

Comes, R.D., V.F. Bruns and A.D. Kelley. 1978. Longevity of certain weed and crop seeds in fresh water. Weed Science. 26(4): 336–344.

COSEWIC. 2010. COSEWIC assessment and status report on Four–leaved Milkweed Asclepias quadrifolia Asclepias quadrifolia in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. x + 40 pp. SARA Registry

Gleason, H. A. and A. Cronquist. 1991. Manual of Vascular Plants of Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada (2nd Ed.). The New York Botantical Garden. Bronx, N.Y. xlvi + 993 pp.

Kartesz, J. 2008. Floristic Synthesis of North America (CD–ROM). Biota of North America Program. Chapel Hill, NC.

Lee, H. T., W.D. Bakowsky, J. Riley, J. Bowles, M. Puddister, P. Uhlig and S. McMurray, 1998. Ecological Land Classification for Southern Ontario: First Approximation and Its Application. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Southcentral Science Section, Science Development and Transfer Branch. SCSS Field Guide FG-02.

Macoun, J. 1883–1890. Catalogue of Canadian plants. Parts 1–5. Geol. Surv. Can., Ottawa.

Morse, D.H. and J. Schmitt. 1985. Propagule size, dispersal ability, and the seedling performance in Asclepias syriaca. Oecologia 67: 372–379.

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. 1998. Guidelines for Mapping Endangered Species Habitats under the Conservation Land Tax Incentive Program. Peterborough, Ontario.

Poisson, G. 2006. Pers. obs. Field observations of Geri Poisson at McMahon Bluff, 2006. Ecologist, Beacon Environmental Ltd. Bracebridge, ON.

Queller, D.C. 1985. Proximate and ultimate causes of low fruit production in Asclepias exaltata. Oikos 44: 373–381.

Reschke, C., R. Reid, J. Jones, T. Feeney and H. Potter. 1999. Conserving Great Lakes Alvars – Final Technical Report of the International Alvar Conservation Initiative. The Nature Conservancy Great Lakes Program. Chicago, IL. 255 pp.

Trustham, T. 2010. Personal Communication. Telephone conversation with Tim Trustham. December 2010. Ecologist/Planner, Quinte Conservation, Belleville, ON.

Woodson, R. E. Jr. 1954. The North American species of Asclepias L. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 41(1):1–221.

Wyatt, R. and S.B. Broyles. 1994. Ecology and Evolution of Reproduction in Milkweeds. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 25: 423–441.

Footnotes

- footnote[1] Back to paragraph Information communicated to Sean Blaney from American botanists, plus that of Cabin et al. (1991) and Chaplin and Walker (1982). Geographic notes and habitat columns are paraphrased directly from emails received. Authorities are natural heritage program botanists unless otherwise noted (Source: COSEWIC 2010).