Lake Erie Watersnake Recovery Strategy

This document is the recovery strategy for a species at risk – the Lake Erie Watersnake.

About the Ontario recovery strategy series

This series presents the collection of recovery strategies that are prepared or adopted as advice to the Province of Ontario on the recommended approach to recover species at risk. The Province ensures the preparation of recovery strategies to meet its commitments to recover species at risk under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) and the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk in Canada.

What is recovery?

Recovery of species at risk is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened, or extirpated species is arrested or reversed, and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of a species’ persistence in the wild.

What is a recovery strategy?

Under the ESA a recovery strategy provides the best available scientific knowledge on what is required to achieve recovery of a species. A recovery strategy outlines the habitat needs and the threats to the survival and recovery of the species. It also makes recommendations on the objectives for protection and recovery, the approaches to achieve those objectives, and the area that should be considered in the development of a habitat regulation. Sections 11 to 15 of the ESA outline the required content and timelines for developing recovery strategies published in this series.

Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for endangered and threatened species within one or two years respectively of the species being added to the Species at Risk in Ontario list. There was a transition period of five years (until June 30, 2013) to develop recovery strategies for those species listed as endangered or threatened in the schedules of the ESA. Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for extirpated species only if reintroduction is considered feasible.

What’s next?

Nine months after the completion of a recovery strategy a government response statement will be published which summarizes the actions that the Government of Ontario intends to take in response to the strategy.

The implementation of recovery strategies depends on the continued cooperation and actions of government agencies, individuals, communities, land users, and conservationists.

For more information

To learn more about species at risk recovery in Ontario, please visit the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry Species at Risk webpage.

Recommended citation

Willson, R.J., and G.M. Cunnington. 2015. Recovery Strategy for the Lake Erie Watersnake (Nerodia sipedon insularum) in Ontario. Ontario Recovery Strategy Series. Prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Foresty, Peterborough, Ontario. vi + 24 pp.

© Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2015

ISBN 978-1-4606-3083-9 (PDF)

Cette publication hautement spécialisée « Recovery strategies prepared under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 », n’est disponible qu’en Anglais en vertu du Règlement 411/97 qui en exempte l’application de la Loi sur les services en français. Pour obtenir de l’aide en français, veuillez communiquer avec Michelle Collins au ministère des Richesses naturelles au

Authors

Robert J. Willson

RiverStone Environmental Solutions Inc.

Glenn M. Cunnington

RiverStone Environmental Solutions Inc.

Acknowledgments

This recovery strategy is based on an earlier draft prepared by Deb Jacobs. The following recovery team members and advisors provided input to the previous draft recovery strategy prepared by Deb Jacobs: Ross Hart, Don Hector, Richard King, Vicki McKay, Ben Porchuk, Jeremy Rouse, Megan Seymour and Allen Woodliffe. The Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry provided the financial support to complete this recovery strategy.

Declaration

The recovery strategy for the Lake Erie Watersnake was developed in accordance with the requirements of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA). This recovery strategy has been prepared as advice to the Government of Ontario, other responsible jurisdictions and the many different constituencies that may be involved in recovering the species.

The recovery strategy does not necessarily represent the views of all of the individuals who provided advice or contributed to its preparation, or the official positions of the organizations with which the individuals are associated.

The goals, objectives and recovery approaches identified in the strategy are based on the best available knowledge and are subject to revision as new information becomes available. Implementation of this strategy is subject to appropriations, priorities and budgetary constraints of the participating jurisdictions and organizations.

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this strategy.

Responsible jurisdictions

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry

Environment Canada – Canadian Wildlife Service, Ontario

Parks Canada Agency

Executive summary

The Lake Erie Watersnake (Nerodia sipedon insularum) is endemic to the islands of the Lake Erie Archipelago and a small portion of the shoreline on the Catawba-Marblehead Peninsula of the Ohio mainland. The Lake Erie Watersnake is listed as endangered under Ontario’s Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA). The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) declared the Lake Erie Watersnake endangered in 1991 and this status was retained in a status update in 2006. The Lake Erie Watersnake is also identified as endangered under Schedule 1 of the Species at Risk Act (SARA). The populations inhabiting the American islands were removed from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s endangered and threatened species list in 2011.

Most Lake Erie Watersnakes have a background colouration of gray or brown and have either no banding pattern or have blotches or banding that are either faded or reduced. The species is live bearing with young being born in late-August to early September. Lake Erie Watersnakes have shifted their diet so that over 92 percent is now composed of the introduced Round Goby. In Ontario the Lake Erie Watersnake is known to occur on four islands (Middle, East Sister, Hen and Pelee) and is believed to no longer occur on Middle Sister and North Harbour Islands. Causes of decline have historically included human persecution and habitat loss and degradation. More recently, road mortality has become a threat to the Lake Erie Watersnake population on Pelee Island, and it is possible that both environmental pollution and elevated predation levels are having adverse effects.

The recovery goal for Lake Erie Watersnake in Ontario is to ensure population persistence by maintaining the current abundance and distribution of the species. The protection and recovery objectives are as follows:

- promote protection of the species and its habitat through education, legislation, policies, stewardship initiatives and land use plans;

- increase the quantity and quality of available habitat for Lake Erie Watersnake on Pelee Island; and

- address knowledge gaps

Lake Erie Watersnakes require a number of different habitats (e.g., hibernation, gestation, shelter, foraging); however, for the purposes of developing a habitat regulation it is recommended that the different types of habitat be grouped into the following two categories as per the American recovery plan for the species: (1) hibernation habitat, and (2) active season habitat.

Given the importance and sensitivity to disturbance of hibernation habitat, it is recommended that this habitat be protected and recognized as having a high sensitivity to alteration. Additional recommendations pertaining to hibernation habitat to be considered in a habitat regulation are as follows:

- hibernation habitat should be protected until it is demonstrated that the feature can no longer function in this capacity;

- the area within 100 m of an identified hibernation feature (single site or complex) should be protected and recognized as having a high sensitivity to alteration; and

- an area that provides suitable hibernation conditions for Lake Erie Watersnake that is within 95 m of the high water mark should be protected.

To provide an acceptable level of protection to active season habitat, it is recommended that the following areas be protected on all islands where the Lake Erie Watersnake is known to occur and that active season habitat be recognized as having a moderate sensitivity to alteration:

- the lands 13 m above the high water mark of Lake Erie containing any of the following features: limestone/dolomite shelves, fragments and ledges, armour stone, cobblestone, vegetation (living or dead), rock, soil and/or brush piles (berms), discarded sheet metal or wooden boards;

- the lands and water below the high water mark out to 13 m beyond the current water level;

- wetlands within 780 m of the high water mark; and

- canals where Lake Erie Watersnakes have been documented, specifically a distance of 450 m up and down the canal from the location of the observation.

1.0 Background information

1.1 Species assessment and classification

- Common name: Lake Erie Watersnake

- Scientific name: Nerodia sipedon insularum

- SARO List Classification: Endangered

- SARO List History: Endangered (2004)

- COSEWIC Assessment History: Endangered (1991, 2006)

- SARA Schedule 1: Endangered (March 5, 2009)

- Conservation status rankings: GRANK: G5 GRANK: N2 GRANK: S2

The glossary provides definitions for technical terms, including the abbreviations above.

1.2 Species description and biology

Species description

Recognized as a distinct taxon by Conant and Clay (1937, 1963), the Lake Erie Watersnake (Nerodia sipedon insularum) is a subspecies of the Northern Watersnake (Nerodia sipedon), that occurs solely on the islands and the Catawba-Marblehead Peninsula of western Lake Erie. Lake Erie Watersnakes possess colour and patterning ranging from strong, regular banding to uniformly beige or grey and unbanded, to variously coloured bands/blotches. The ventral surface is generally white to yellowish usually with dark speckling or stippling (Rowell 2012). The dorsal colour pattern variation of Lake Erie Watersnakes (e.g., reduced bands/blotches) as well other diet and morphological characteristics distinguish the subspecies from the Northern Watersnake (see USFWS 2003, Rowell 2012 and references therein for summary). The body scales are keeled and there is a single anal plate (Conant and Collins 1998). Adult male Lake Erie Watersnakes average between 59.1 and 71.6 cm snout-to-vent length (SVL), whereas adult females generally attain lengths between 80.2 and 88.2 cm SVL (King 1986). When approached, Lake Erie Watersnakes usually retreat quickly into the water or under cover objects. Lake Erie Watersnakes may bite when handled but are non-venomous. Other defensive behaviours when being handled include writhing and exuding a foul-smelling fluid from the anal glands.

Species biology

The Lake Erie Watersnake is ovoviviparous, meaning they give birth to live young (i.e., live bearing) (Ernst and Ernst 2003). Studies on Pelee Island documented an average litter size of 27.2 ± 9.20 (range 13–46) for 30 Lake Erie Watersnakes (Brooks et al. 2000). Young are born from late August to early September (COSEWIC 2006). Lake Erie Watersnakes are most often found in close proximity to the water’s edge; however, individuals have been documented moving inland up to 580 m to hibernate (King 2002a). Although movements between islands of the Lake Erie archipelago are likely uncommon, both measurements of genetic diversity (King and Lawson 1995) and mark- recapture data show that these relatively long distance movements do occur (e.g., minimum distance moved between Kelleys Island and Middle Island of 11 km; D. Jacobs unpub. data). The diet of the Lake Erie Watersnake has historically consisted mainly of small fish and amphibians (King et al. 2006b). With the introduction of the Round Goby (Apollonia melanostomus) in the early 1990s (Fernie et al. 2008), Lake Erie Watersnakes have shifted their diet so that over 92 percent is composed of Round Gobies (King et al. 2006b). Since this change in diet the snakes have been documented to attain larger body sizes, accelerated growth rates and increased fecundity (King et al. 2006b).

Lake Erie Watersnakes hibernate underground for five to seven months each year (generally mid-September through mid-April) and both communal and single occupancy hibernacula have been documented (USFWS 2003, COSEWIC 2006).

1.3 Distribution, abundance and population trends

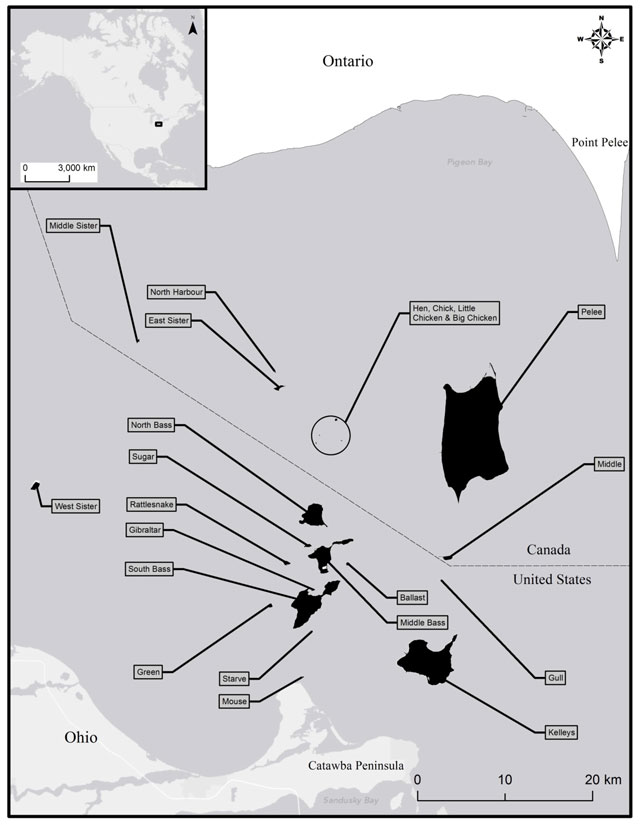

The Lake Erie Watersnake is restricted to the islands of the Lake Erie Archipelago and a small shoreline area of the Catawba-Marblehead Peninsula in Ohio (Figure 1) (but see USFWS 2003 for discussion of intergrades with Northern Watersnake on the peninsula). The Lake Erie Archipelago consists of 22 islands: nine Canadian (Pelee, Middle, Hen, Chick, Little Chicken, Big Chicken, East Sister, North Harbour and Middle Sister) and 13 American (North Bass, Middle Bass, South Bass, Kelleys, Rattlesnake, Green, Gull, Sugar, Gibraltar, Starve, Ballast, Lost Ballast and West Sister). Reports dating back to 1893 suggest that Lake Erie Watersnakes may have been observed on all of the islands in the western basin of Lake Erie. The smallest of the Canadian islands are little more than reefs which in high water levels or storm events are underwater or nearly so. While it is possible that a Lake Erie Watersnake may visit these islands occasionally to forage or while moving between the other islands, there is no evidence at this time to indicate that these islands function as habitat for this species.

In Ontario, Lake Erie Watersnakes are still known to occur on East Sister, Hen, Middle and Pelee Islands (COSEWIC 2006). Whether the species still occurs on North Harbour or Middle Sister is unknown; however, as reported in King et al. (1997), researchers failed to find occupancy during recent surveys. In 2003 Canadian researchers requested permission from the landowners of these two islands (as well as Hen Island) to survey for snakes but were refused (D. Jacobs unpub. data).

The values calculated for the extent of occurrence and area of occupancy in Canada as reported in COSEWIC (2006) are 188 km2 and 24 km2 respectively.

Based on fieldwork conducted in the early 1980s, King (1986) estimated the population along a 4.8 km section of shoreline to be 489 adults (95% confidence intervals between 205 and 1,547 adults). Surveys conducted between 1988 and 1992 along 4.65 km of shoreline estimated that the population had decreased to 391 adults (King 2002b as cited in COSEWIC 2006). The number of mature Lake Erie Watersnakes estimated in COSEWIC (2006) to be on Pelee Island was 410 (95% confidence interval = 200–1,500).

Concerning the population trends for Lake Erie Watersnakes on the American islands, King et al. (2006a) demonstrated that population levels estimated at their primary study areas exceeded the targets specified in the species’ recovery plan (USFWS 2003). Population targets were based on estimates of viable population sizes generated using IUCN (2001) criteria and demographic data collected on the Lake Erie Watersnake by R. King (USFWS 2003). Because key recovery objectives were achieved including exceeding population targets, the Lake Erie Watersnake was removed from the U.S. list of federally endangered and threatened species on August 16, 2011 (USFWS 2011).

1.4 Habitat needs

For many live-bearing snakes inhabiting northern latitudes, the three most important types of habitat in order of importance, are (1) hibernation habitats, (2) gestation habitats and (3) shelter habitats (e.g., features that facilitate ecdysis, digestion and protection from predators). Although these three habitats are the most important for maintaining viable populations other habitats used for foraging, mating and movement are necessary for population persistence.

Based on radiotelemetry studies completed by King (2002a, 2002b, 2004), the USFWS (2003) categorized all of the habitats used by Lake Erie Watersnake into two groups: “Essential Summer Habitat” and “Essential Hibernation Habitat.” Given that the radiotelemetry studies on Lake Erie Watersnake conducted by King (2002a, 2002b, 2004) were more extensive than those conducted by the OMNRF, this classification into two habitat categories has been adopted for this recovery strategy with the exception that summer habitat will be referred to as active season habitat and the word “essential” has been removed as a modifier.

Hibernation habitat

Cracks and fissures in bedrock, rock and soil piles and berms, rodent burrows in soil substrates, root masses, building foundations, drainage tiles and old wells have been used as hibernation habitat (USFWS 2003, COSEWIC 2006). Adult snakes may hibernate singly or communally (USFWS 2003; D. Jacobs unpub. data), and occasionally hibernation areas are shared with Eastern Foxsnakes (Pantherophis gloydi), Blue Racers (Coluber constrictor foxii) and Eastern Gartersnakes (Thamnophis sirtalis sirtalis) (Porchuk and Willson unpub. data).

In Ontario radiotracked Lake Erie Watersnakes hibernated at sites at least 13 m from the water’s edge (range = 13–105 m; mean = 53 m). Fifty percent of the hibernation sites were within 56 m of the shore, 75 percent were within 69 m and 90 percent were within 95 m of shore (D. Jacobs unpub. data, COSEWIC 2006). On Pelee Island probable locations for hibernacula have been identified up to 500 m from the shore based on observations of snakes early in the spring that were located at sites with the potential to function as hibernation habitat based on physical characteristics (Willson, unpub. data). It may be noteworthy that many of the Lake Erie Watersnakes found greater than 95 m from the shore are juveniles (Willson unpub. data).

On the U.S. islands 75 percent of the radiotracked Lake Erie Watersnakes hibernated within 69 m of the shoreline (USFWS 2003). Emergence from hibernacula usually occurs in mid-to-late April or early May (Willson unpub. data). Within one to one-and-a- half months after emergence, most Lake Erie Watersnakes will have dispersed from hibernacula towards the Lake Erie shoreline where they can be found under rocks, in rock berms, in woody debris or brush piles, under wooden boards or pieces of refuse washed upon the beach and underground (D. Jacobs unpub. data).

Active season habitat

This category encompasses habitats used for basking, gestation, shelter, foraging, mating, birthing and movement. With the exception of inland movements to hibernation habitats, the USFWS (2003) found that the majority of Lake Erie Watersnakes were active within 13 m of the water’s edge (in-water and terrestrial), that is, during the active season 75 percent of the individuals radiotracked were within 13 m (King 2003).

Within the terrestrial portion of this shoreline band, Lake Erie Watersnakes use limestone/dolomite shelves, fragments and ledges, armour stone, cobblestone, vegetation (living or dead), rock and/or soil piles (berms) and discarded sheet metal or wooden boards. These features are used by Lake Erie Watersnakes for basking, gestation, shelter, mating and birthing. Sandy shorelines, which are more common on Pelee than other islands that do not have rock or vegetation within a few metres of the water seem to be used less frequently (Jacobs, Willson, Porchuk unpub. data). However, Lake Erie Watersnakes have been observed moving onto sandy beaches to finish swallowing prey items (Willson unpub. data), and they have been observed resting or basking in these areas (J. Crowley pers. comm.).

Lake Erie Watersnakes forage in water along the shoreline, in canals and in wetlands (Porchuk unpub. data). Foraging in the water along shorelines occurs primarily within a 13 m band as documented in USFWS (2003) and activity occurs almost entirely within 50 m of the shoreline (COSEWIC 2006, D. Jacobs unpub. data). USFWS (2003) found that the linear extent of shoreline used by 75 percent of the snakes they were radiotracking was 437 m or less. Similar to hibernation habitat Lake Erie Watersnakes exhibit fidelity to specific areas or features along the shoreline (USFWS 2003, D. Jacobs unpub. data). On Pelee Island Lake Erie Watersnakes have been documented in the canals that drain parts of the island and have also been found using inland ponds/wetlands created by quarrying activities (Porchuk and Willson unpub. data).

1.5 Limiting factors

The small geographic range of the Lake Erie Watersnake and the small population sizes on some of the islands make it vulnerable to extinction from demographic and environmental stochasticity, catastrophic events and loss of genetic variability (Caughley 1994, Burkey 1995). This phenomenon may have already occurred on some of the Lake Erie islands where Lake Erie Watersnakes have been extirpated (e.g. West Sister Island, USFWS 2003). The fact that populations inhabiting smaller islands are vulnerable to extinction has been understood since MacArthur and Wilson (1967) (i.e. the theory of island biogeography). For taxa such as the Lake Erie Watersnake that are restricted to small geographic areas composed of islands this phenomenon is certainly a limiting factor.

1.6 Threats to survival and recovery

Intentional persecution

A significant proportion of the human population harbours a dislike or fear of snakes and this dislike seems to increase with snakes that inhabit areas where people swim (Willson and Porchuk unpub. data). Lake Erie Watersnakes can grow to be fairly large and they are easily visible along the shoreline of the Erie Islands where they occur (COSEWIC 2006). They will also use areas in close proximity to humans and can readily be found in boats and even in and around human dwellings.

While not venomous, Lake Erie Watersnakes will often strike or bite when provoked, cornered or handled (COSEWIC 2006). These characteristics have resulted in intentional killing at the hands of misinformed people. In addition to haphazard persecution Campbell (1991) compiled a number of accounts of snake extermination campaigns that targeted this species including on Rattlesnake Island (Ohio) and Middle Island. As documented in COSEWIC (2006) and USFWS (2003) the Lake Erie Watersnake has been heavily collected and persecuted over the last 150 years. In 2006 several dead Lake Erie Watersnakes were found on both Middle Island and East Sister Island under suspicious circumstances, and while the cause of death cannot be confirmed, it is most consistent with human persecution (D. Jacobs, unpub. data). On both the Canadian and American islands, some landowners see the snake’s protected status as a threat to their private property rights or an impediment to development (Olive 2012).

Vehicular mortality

Pelee Island is the only Canadian island in the Lake Erie Archipelago with roads.

Almost the entirety of Pelee is encircled by a road in close proximity to the water’s edge. Observations of road-killed Lake Erie Watersnakes have been made regularly over the years by naturalists and OMNRF staff. The colouration of Lake Erie Watersnakes may make them difficult to see against unpaved or dust covered roads, and this species will often cease moving when approached by a vehicle or human (Willson unpub. data). Additionally, Ashley et al. (2007) quantitatively demonstrated that a subset of the snakes killed by motor vehicles on roads is run over intentionally.

Roadkill surveys were conducted for all snake species on Pelee Island from 1993 to 1995 (Brooks and Porchuk 1997), 1998 to 1999 (Brooks et al. 2000) and during the springs of 2000 to 2002 (Willson 2002). Although the primary intent of these surveys was to document the distribution of the Lake Erie Watersnake on Pelee Island, the following values provide an estimate of how many individuals can be killed on the island’s roads in peak years.

In 1995, there were 64 Lake Erie Watersnakes found dead on Pelee Island’s roads (Brooks et al. 2000). Researchers did not record the age class of road-killed Lake Erie Watersnakes during this survey period; however, only 4 of the 64 records were recorded in August when newborn snakes would be present and the road survey was not conducted in September (Willson and Porchuk unpub. data). Therefore 60 of the road-killed Lake Erie Watersnakes were adults, juveniles or yearlings (snakes born the previous year). During the spring surveys of 2000 to 2002 (April 13 to May 15), there were 12 adults, two juveniles and seven yearlings (age classes based on King 1986) documented as roadkills (Willson 2002). Eight of the adult roadkills were female (Willson unpub. data).

Based on these data it is evident that numerous Lake Erie Watersnakes are killed by automobiles on the island’s roads each spring when they are presumably moving from inland hibernation habitat to active season habitat along the shoreline. It is reasonable to infer that Lake Erie Watersnakes are also killed regularly on the roads in September and October as they move from active season habitat along the shoreline to inland hibernation habitat. However roadkill surveys have not been conducted during this time of year (Willson and Porchuk unpub. data). It is unknown whether mortality at the levels documented is likely to incur long-term population consequences similar to that determined by Row et al. (2007) for Gray Ratsnakes (Pantherophis spiloides) in eastern Ontario. However, given that the other Canadian islands only support small populations of Lake Erie Watersnake, road mortality on Pelee Island’s roads is likely a significant threat to survival and recovery.

Lake Erie Watersnakes are also susceptible to injuries or death inflicted by other motorized vehicles. Lawnmowers have been observed to cause mortality in this species (Porchuk unpub. data) and it seems plausible that boat propellers inflict occasional damage as well.

Habitat loss and degradation

Vegetation clearing, mowing and spraying, infilling, rock berm disruption, shoreline hardening and general shoreline property clean-up can all damage or destroy habitat for Lake Erie Watersnake (USFWS 2003; COSEWIC 2006). In at least one instance a known communal hibernaculum on Pelee Island was destroyed on private land during such a clean-up in the late 1990s (Woodliffe and Porchuk unpub. data). Additionally, shoreline development that results in the aforementioned activities reduces the quantity and quality of habitat for Lake Erie Watersnakes (COSEWIC 2006).

It is possible that the invasive Common Reed (Phragmites australis) could reduce habitat quality and availability for Lake Erie Watersnake in areas where the plant’s density reduces solar radiation to levels too low for individuals of the species to maintain preferred body temperatures. Currently there are areas in Lighthouse Point Provincial Nature Reserve where Common Reed occurs at these densities and provide seemingly poor habitat conditions for Lake Erie Watersnakes (Willson unpub. data).

Middle and East Sister Islands are provincially protected nature reserves, therefore no sanctioned habitat loss or degradation should occur. North Harbour Island has been highly modified by its owner thus there does not appear to be much habitat remaining for Lake Erie Watersnake. Middle Sister Island and Hen Island are both privately owned and are difficult to monitor. The Chick Islands (collective name for Big Chicken, Little Chicken and Chick Islands) are little more than reefs and likely do not face development threats although they probably offer only minimal, low-quality transitory habitat for Lake Erie Watersnakes. Although Lake Erie Watersnake habitat on these islands is protected by provincial and federal legislation and policy, monitoring and enforcement are difficult because these islands are relatively inaccessible.

It is unknown whether the alteration of the ground cover and tree communities on Middle and East Sister Islands by the guano of Double-crested Cormorants will have an adverse effect on Lake Erie Watersnakes.

Environmental contamination

Fernie et al. (2008) found that Lake Erie Watersnakes at the three sites sampled on Pelee Island had some of the lowest mean concentrations of sum polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) and dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (DDE) levels reported in their study. However, it remains to be determined whether the concentrations observed would have negative effects on the reproductive parameters of female Lake Erie Watersnake particularly embryonic survival (Fernie et al. 2008).

Predation

Predation of young Lake Erie Watersnakes by Double-crested Cormorants (Phalacrocorax auritus) may be a threat on Middle and East Sister Islands. The Canadian Wildlife Service has been monitoring these birds since their arrival in the area in the early 1980s and populations reached an all-time high in the past couple of years, with close to 6,000 nests per island (C. Weseloh, unpub. data), representing an approximate population of 24,000 birds per island (assuming two adults and two young per nest). In 2001, snake researchers found a juvenile Lake Erie Watersnake that appeared to have been killed (but not eaten) by an unknown species of bird (D. Jacobs, unpub. data). However, evidence that Double-crested Cormorants prey upon Lake Erie Watersnakes is lacking and the USFWS (2003) did not consider this risk of predation to be a potential threat to American populations of Lake Erie Watersnakes.

1.7 Knowledge gaps

Relative to many other species at risk much is known about the Lake Erie Watersnake. As such there are many recovery activities for this species that can be implemented immediately. However, there are still some aspects of this species’ biology that are unknown and further investigation into these subjects would help direct recovery efforts. Knowledge that is lacking for Lake Erie Watersnake in Canada includes:

- population estimates for the entirety of Pelee Island;

- level of use of inland canals and waterways (and the lands surrounding them);

- impact of road mortality on Lake Erie Watersnake population on Pelee Island;

- presence/absence surveys for Hen, Middle Sister and North Harbour Islands;

- use of habitats created as part of conservation efforts;

- understanding of physical and chemical structure of hibernacula;

- impact of changing bird populations on the Lake Erie Watersnake’s populations on Middle and East Sister Island; and

- impact of contamination on the Lake Erie Watersnake.

1.8 Recovery actions completed or underway

Habitat protection and management

- Ontario’s Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA; Government of Ontario 2007) came into force in 2008. General habitat protection is provided for Lake Erie Watersnake under Section 10 of the ESA.

- As of 2012, the following properties were known to contain Lake Erie Watersnake habitat and were owned by organizations that have natural heritage protection as one of their primary objectives:

- Lighthouse Point Provincial Nature Reserve (OMNRF);

- Fish Point Provincial Nature Reserve (OMNRF);

- East Sister Island Nature Reserve (OMNRF);

- Stone Road Alvar Conservation Area (Essex Region Conservation Authority);

- Middle Island (Parks Canada);

- Stone Road Alvar (see Nature Conservancy of Canada (NCC) 2008); and

- Middle Point Woods (see Nature Conservancy of Canada (NCC) 2008).

Management at these properties has varied according to the objectives of the responsible agencies.

- The owners of some additional lands with Lake Erie Watersnake habitat have entered into conservation easements with the NCC.

- Landowners whose properties contain Lake Erie Watersnake habitat (with certain size restrictions) are eligible to apply to participate in the Conservation Land Tax Incentive Program (CLTIP). This program offers 100 percent tax relief to landowners for the portion of their property that was considered to be endangered species habitat.

Public outreach

- In 1989 wildlife-crossing signs were erected along roads on Pelee Island specifically warning motorists to be aware of snakes crossing the roads. These signs were almost immediately removed or vandalized (Porchuk 1998).

- A natural heritage video was created in 1995 by several government and non- government conservation agencies including the Pelee Island Heritage Centre, and was played in the passenger lounge on every ferry connecting Pelee Island with the Ontario mainland for several years. However, it has not been updated and is no longer played (Porchuk 1998). Copies of the video were also made available for sale. The informative nature of this video may have helped reduce road mortality and direct persecution by educating tourists.

- In 1995 a pamphlet was designed by the Pelee Island Heritage Centre, Essex Region Conservation Authority, Ontario Nature and the Ontario Heritage Foundation and was made available on the ferry and at the Heritage Centre. The pamphlet provided information on several rare and endangered flora and fauna on Pelee Island including the Lake Erie Watersnake. Information on how tourists and residents could help to conserve rare species was included. This pamphlet is currently out of print (MacKinnon 2005).

- In addition to the natural heritage video and pamphlet, the Pelee Island Heritage Centre also sold conservation T-shirts as a public outreach initiative.

- In an effort to show that the preservation of endangered species can be beneficial to the community and local economy, the Wilds of Pelee Island held an Endangered Species Festival on the island in 2001, 2002 and in 2003. It is estimated that $16,000 was generated for the Pelee Island economy during the festival thus demonstrating that conserving endangered species and their habitats could benefit the island economy through eco-tourism. In 2003, the festival was combined with the 8th Annual Meeting of the Canadian Amphibian and Reptile Conservation Network bringing in over 220 people from Ontario, and other regions of Canada and the United States (MacKinnon 2005).

- In 2003, the Wilds of Pelee Island published a 72-page, colour guide entitled Pelee Island Human and Natural History: Guide to a Unique Island Community.

Photos and text concerning the Lake Erie Watersnake and other species at risk were featured in the publication.

Research and monitoring

- Several dozen properties have been visited by OMNRF staff to advise landowners regarding endangered species habitat.

- Radiotelemetry studies were conducted by OMNRF staff and R. Willson on Pelee, Middle and East Sister Islands from 2001 to 2003. A total of 23 snakes were tracked over this period and 12 hibernacula were located (D. Jacobs unpub. data).

- Mark-recapture surveys were conducted by OMNRF staff and volunteers on Middle and East Sister Island from 2001 to 2005 (D. Jacobs unpub. data).

- Visual surveys and limited mark-recapture surveys were conducted on Pelee Island in 2004 to determine population levels and relative density by shoreline type.

- Two hibernacula were constructed within Fish Point and Lighthouse Point Provincial Nature Reserves for Lake Erie Watersnake, Blue Racer and Eastern Foxsnake (Willson and Porchuk 2001).

- Roadkill surveys were conducted for all snake species from 1993 to 1995 (Brooks and Porchuk 1997), 1998 to 1999 (Brooks et al. 2000) and during the springs of 2000 to 2002 (Willson 2002).

- Toxicological analysis, mark recapture and counts of littler size of gravid females was conducted in 1999 (Brooks et al. 2000).

- Surveys of select sites on Pelee Island and other Islands were conducted by R. King in the 1980s and early 1990s and population estimates were generated at that time.

2.0 Recovery

2.1 Recovery goal

The recovery goal for Lake Erie Watersnake in Ontario is to ensure population persistence by maintaining the current abundance and distribution of the species.

2.2 Protection and recovery objectives

Table 1. Protection and recovery objectives

Table 1. has been converted to a list

- Promote protection of the species and its habitat through education, legislation, policies, stewardship initiatives and land use plans

- Increase the quantity and quality of available habitat for Lake Erie Watersnake on Pelee Island

- Address knowledge gaps

2.3 Approaches to recovery

Table 2. Approaches to recovery of the Lake Erie Watersnake in Ontario

<

| Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Ongoing |

Communications Education and Outreach |

1.1 Increase landowner communications.

|

|

| Necessary | Ongoing |

Communications Education and Outreach |

1.2 Support the Pelee Island Heritage Centre and other island-based conservation and stewardship organizations to:

|

|

| Necessary | Long-term | Stewardship |

1.3 Improve implementation of conservation incentive programs.

|

|

| Necessary | Short-term |

Protection Management Education and Outreach |

1.4 Develop and effectively implement a habitat regulation and/or habitat description for Lake Erie Watersnake under the ESA.

|

|

| Necessary | Short-term |

Communications Education and Outreach |

1.5 Develop Best Management Practices for minimizing negative impacts on species and habitat.

|

|

| Necessary | Long-term |

Communications Education and Outreach |

1.6 Produce Fact Sheets.

|

|

| Necessary | Ongoing |

Communications Education and Outreach Stewardship |

1.7 Produce Stewardship publications.

|

|

| Beneficial | Long-term |

Communications Education and Outreach |

1.8 Produce educational materials for children and youth.

|

|

| Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Short-term | Protection Management |

2.1 Increase amount of habitat available for Lake Erie Watersnake.

|

|

| Necessary | Short-term |

Communications Education and Outreach |

2.2 Provide technical support for habitat creation.

|

|

| Necessary | Short-term | Protection Management |

2.3 Assess quantity and quality of Lake Erie Watersnake habitat.

|

|

| Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Necessary | Long-term | Research |

3.1 Conduct mark-recapture surveys at select sites on Pelee Island.

|

|

| Necessary | Ongoing | Monitoring Research |

3.2 Determine whether any of the hibernation habitats that have been created are being used by Lake Erie Watersnakes.

|

|

| Necessary | Ongoing | Monitoring | 3.3 Conduct presence/absence surveys on Hen, Middle Sister and North Harbour Islands. |

|

| Necessary | Long-term | Research |

3.4 Research subsurface structure of hibernation sites.

|

|

| Beneficial | Long-term | Research | 3.5 Determine the effect (if any) of changing bird populations on Middle, East Sister and Middle Sister Island on Lake Erie Watersnake. |

|

| Beneficial | Long-term | Monitoring | 3.6 Support research examining the effect of documented contaminant levels on reproductive health of females. |

|

2.4 Area for consideration in developing a habitat regulation

Under the ESA 2007, a recovery strategy must include a recommendation to the Minister of Natural Resources and Forestry on the area that should be considered in developing a habitat regulation. A habitat regulation is a legal instrument that prescribes an area that will be protected as the habitat of the species. The recommendation provided below by the authors will be one of many sources considered by the Minister when developing the habitat regulation for this species.

Lake Erie Watersnakes require a number of different habitats (e.g., hibernation, gestation, shelter, foraging). However, for the purposes of developing a habitat regulation, it is recommended that the different types of habitat be grouped into the following two categories as per the American recovery plan for the species (USFWS 2003): (1) hibernation habitat and (2) active season habitat.

Hibernation habitat

Given the importance and sensitivity to disturbance of hibernation habitat, it is recommended that this habitat be protected and recognized as having a high sensitivity to alteration. Additional recommendations pertaining to hibernation habitat to be considered in a habitat regulation are as follows:

- hibernation habitat should be protected until it is demonstrated that the feature can no longer function in this capacity;

- the area within 100 m of an identified hibernation feature (single site or complex) should be protected and recognized as having a high sensitivity to alteration; and

- an area that provides suitable hibernation conditions (see Hibernation Habitat in Section 1.4) for Lake Erie Watersnake that is within 95 m of the high water mark should be protected.

Rationale

The area within 100 m of a hibernation feature should be regulated as habitat to ensure that Lake Erie Watersnakes are protected in the spring after they emerge from hibernation habitats and have not yet moved to shoreline locations.

In Ontario, 12 radiotracked Lake Erie Watersnakes hibernated at sites at least 13 m from the water’s edge (range = 13–105 m; mean = 53 m). Fifty percent of the hibernation sites were within 56 m of the shore, 75 percent were within 69 m and 90 percent were within 95 m of shore (COSEWIC 2006). It is unknown how the water’s edge measured by the OMNRF (D. Jacobs unpub. data) during the radiotelemetry studies on Lake Erie Watersnake relates to the high water mark of Lake Erie.

To account for changing water levels in Lake Erie the recommended 95 m distance inland should be measured from the high water mark. Because a very small portion of the hibernation habitat on Pelee and the other Canadian islands has been identified, protecting areas with suitable conditions would be a prudent cautionary approach.

Active season habitat

Additional recommendations pertaining to active season habitat to be considered in a habitat regulation are as follows. Note that this category encompasses habitats used for basking, gestation, shelter, foraging, mating, birthing and movement.

To provide an acceptable level of protection to this active season habitat it is recommended that the following areas be protected on all islands where the Lake Erie Watersnake is known to occur and that active season habitat be recognized as having a moderate sensitivity to alteration:

- the lands 13 m above the high water mark of Lake Erie containing any of the following features: limestone/dolomite shelves, fragments and ledges, armour stone, cobblestone, vegetation (living or dead), rock, soil and/or brush piles (berms), discarded sheet metal or wooden boards;

- the lands and water below the high water mark out to 13 m beyond the current water level;

- wetlands within 780 m of the high water mark; and

- canals where Lake Erie Watersnakes have been documented, specifically a distance of 450 m up and down the canal from the location of the observation.

Rationale

With the exception of inland movements to hibernation habitats, the USFWS (2003) found that the majority of Lake Erie Watersnakes were active within 13 m of the water’s edge (in-water and terrestrial), that is, during the active season 75 percent of the individuals radiotracked were within 13 m (King 2003). It is unknown how the water’s edge measured by the USFWS (2003) during the radiotelemetry studies on Lake Erie Watersnake relates to the high water mark of Lake Erie. To account for changing water levels in Lake Erie the recommended 13 m distance inland should be measured from the high water mark.

On Pelee Island, the farthest distance inland that Lake Erie Watersnakes have been documented using wetlands as active season habitat is 780 m from the approximate water’s edge (R. Willson unpub. data). USFWS (2003) found that the linear extent of shoreline used by 75 percent of the snakes they were radiotracking was 437 m or less. This distance has been used for the recommendation to protect 450 m up and down a canal from a documented Lake Erie Watersnake observation.

Glossary

- Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC)

- The committee established under section 14 of the Species at Risk Act that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Canada.

- Committee on the Status of Species at Risk in Ontario (COSSARO)

- The committee established under section 3 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Ontario.

- Conservation status rank

-

A rank assigned to a species or ecological community that primarily conveys the degree of rarity of the species or community at the global (G), national (N) or subnational (S) level. These ranks, termed G-rank, N-rank and S-rank, are not legal designations. The conservation status of a species or ecosystem is designated by a number from 1 to 5, preceded by the letter G, N or S reflecting the appropriate geographic scale of the assessment. The numbers mean the following:

1 = critically imperilled

2 = imperilled

3 = vulnerable

4 = apparently secure

5 = secure - Ecdysis

- The regular molting or shedding of an outer covering layer (e.g. of skin).

- Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA)

- The provincial legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Ontario.

- Endemic

- Term used for a species that is unique to a particular geographic location.

- Fecundity

- Potential fertility or the capability of repeated fertilization of a given individual or population over a period of time.

- Gestation

- The period in animals bearing live young from the fertilization of the egg to birth of the young (parturition).

- High water mark

- The highest level or elevation reached by a body of water.

- Species at Risk Act (SARA)

- The federal legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Canada. This act establishes Schedule 1 as the legal list of wildlife species at risk. Schedules 2 and 3 contain lists of species that at the time the Act came into force needed to be reassessed. After species on Schedule 2 and 3 are reassessed and found to be at risk, they undergo the SARA listing process to be included in Schedule 1.

- Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) List

- The regulation made under section 7 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that provides the official status classification of species at risk in Ontario. This list was first published in 2004 as a policy and became a regulation in 2008.

- Ventral

- The anterior or lower surface of an animal opposite the back (opposite of dorsum).

References

Ashley, E.P., A. Kosloski, and S.A. Petrie. 2007. Incidence of intentional vehicle-reptile collisions. Human Dimensions of Wildlife 12:137-143.

Brooks, R.J. and B.D. Porchuk. 1997. Conservation of the endangered blue racer snake (Coluber constrictor foxii) on Pelee Island, Canada. Report prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. 26 pp.

Brooks, R.J., R.J. Willson, and J.D. Rouse. 2000. Conservation and ecology of three rare snake species on Pelee Island. Unpublished report for the Endangered Species Recovery Fund. 21 pp.

Burkey, T.V. 1995. Extinction rates in archipelagoes: implications for populations in fragmented habitats. Conservation Biology 9:527-541.

Campbell, C.A. 1991. Status of the Lake Erie water snake, Nerodia sipedon insularum, in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. 29 pp.

Caughley, G. 1994. Directions in conservation biology. Journal of Animal Ecology 63:215-244.

Conant, R. and W. Clay. 1937. A new subspecies of water snake from islands in Lake Erie. Occasional papers of the University of Michigan Museum of Zoology 346:1-9.

Conant, R. and W. Clay. 1963. A reassessment of the taxonomic status of the Lake Erie water snake. Herpetologica 19:179-184.

Conant, R. and J.T. Collins. 1998. A field guide to reptiles and amphibians of eastern and central North America. 3rd, expanded edition. Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston, Massachusetts.

COSEWIC. 2006. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Lake Erie Watersnake Nerodia sipedon insularum in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vii + 23 pp.

Crowley, Joe, pers. comm. 2013. Correspondence to R. Willson. August 2013. Herpetology Species at Risk Specialist, Species at Risk Branch, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. Peterborough, Ontario.

Ernst, C.H. and E.M. Ernst. 2003. Snakes of the United States and Canada. The Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Fernie, K.J., R.B. King, K.G. Drouillard, and K.M. Stanford. 2008. Temporal and spatial patterns of contaminants in Lake Erie Watersnakes (Nerodia sipedon insularum) before and after the Round Goby (Apollonia melanostomus) invasion. Science of the Total Environment 406:344-351.

Government of Ontario. 2007. Endangered Species Act, 2007, S.O. 2007, c 6. IUCN. 2001. IUCN red list categories and criteria: version 3.1. Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK: IUCN Species Survival Commission. ii + 30 p.

King, R.B. 1986. Population ecology of the Lake Erie water snake, Nerodia sipedon insularum. Copeia 1986:757-772.

King, R.B. 2002a. (November 2). Hibernation, seasonal activity, movement patterns, and foraging behavior of adult Lake Erie water snakes (Nerodia sipedon insularum). Quarterly report to the Ohio Division of Wildlife and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 27 pp.

King, R.B. 2002b. Hibernation, seasonal activity, movement patterns, and foraging behavior of adult Lake Erie Watersnakes (Nerodia sipedon insularum), Quarterly Report. Submitted to Ohio Division of Wildlife and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2 July 2002. Unpublished report. 50 pp.

King, R.B. 2004. Hibernation, seasonal activity, movement patterns, and foraging behavior of adult Lake Erie water snakes (Nerodia sipedon insularum). Annual report to the Ohio Division of Wildlife and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 40 pp.

King, R.B. and R. Lawson. 1995. Color-pattern variation in Lake Erie water snakes: the role of gene flow. Evolution 49:885-896.

King, R.B., M.J. Oldham, W.F. Weller, and D. Wynn. 1997. Historic and current amphibian and reptile distributions in the island region of western Lake Erie. American Midland Naturalist 138:153-173.

King, R.B., A. Queral-Regil, and K.M. Stanford. 2006a. Population size and recovery criteria of the threatened Lake Erie watersnake: integrating multiple methods of population estimation. Herpetological Monographs 20:83-104.

King, R.B., J.M. Ray, and K.M. Stanford. 2006b. Gorging on gobies: beneficial effects of alien prey on a threatened vertebrate. Canadian Journal of Zoology 84:108-115.

MacArthur, R.H., and E.O. Wilson. 1967. The theory of island biogeography. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey.

MacKinnon, C.A. 2005. (March 2005 Draft). National recovery plan for the Blue Racer (Coluber constrictor foxii). Recovery of Nationally Endangered Wildlife (RENEW). Ottawa, Ontario.

Nature Conservancy of Canada (NCC). 2008. Management guidelines: Pelee Island alvars. NCC–Southwestern Ontario Region. London, Ontario. 43 pp.

Olive, A. 2012. Endangered species policy in Canada and the US: a tale of two islands. American Review of Canadian Studies 42:84-101.

Porchuk, B.D. 1998. Canadian Blue Racer snake recovery plan. Report prepared for the Recovery of Nationally Endangered Wildlife (RENEW) committee. 55 pp.

Row, J.R., G. Blouin-Demers, and P.J. Weatherhead. 2007. Demographic effects of road mortality in black ratsnakes (Elaphe obsoleta). Biological Conservation 137:117-124.

Rowell, J.C. 2012. The Snakes of Ontario: Natural History, Distribution, and Status. Art Bookbindery, Canada.

United States Fish and Wildlife Service [USFWS]. 2003. Lake Erie Watersnake (Nerodia sipedon insularum) recovery plan. US Fish and Wildlife Service. Fort Snelling, MN. 111 pp. + 7 appendices.

United States Fish and Wildlife Service [USFWS]. 2011. Federal register final rule: removal of the Lake Erie watersnake (Nerodia sipedon insularum) from the federal list of endangered and threatened wildlife. Web site: http://www.fws.gov/midwest/endangered/reptiles/lews/FRlewsFinalRuleDelistAug2011.html [link inactive] [accessed May 18, 2013].

Willson, R.J. 2002. A systematic search for the blue racer (Coluber constrictor foxii) on Pelee Island (2000-2002). Final report prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. 38 pp. + digital appendices.

Willson, R.J. and B.D. Porchuk. 2001. Blue Racer and Eastern Foxsnake habitat feature enhancement at Lighthouse Point and Fish Point Provincial Nature Reserves. 2001 final report. Report prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. 11 pp.