Mississagi River Provincial Park Management Statement

This document provides policy direction for the protection, development and management of Mississagi River Provincial Park and its resources.

Interim Management Statement

Ontario, 2007

Approval statement

I am pleased to approve this Interim Management Statement for Mississagi River Provincial Park. The original park was regulated under the Provincial Parks Act in 1974 (O. Reg. 451/74). The Mississagi River Additions, identified by Ontario’s Living Legacy Land Use Strategy (OMNR 1999) were added to the park, and regulated in May of 2003 (O. Reg. 210/03).

This Interim Management Statement provides direction for the protection and management of Mississagi River Provincial Park.

Signed by:

Paul Bewick, Manager

Northeast Zone

Ontario Parks

Date: March 7, 2007

1.0 Introduction

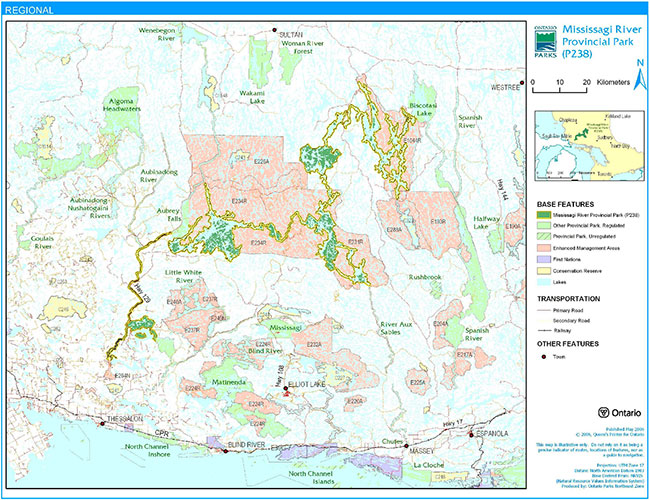

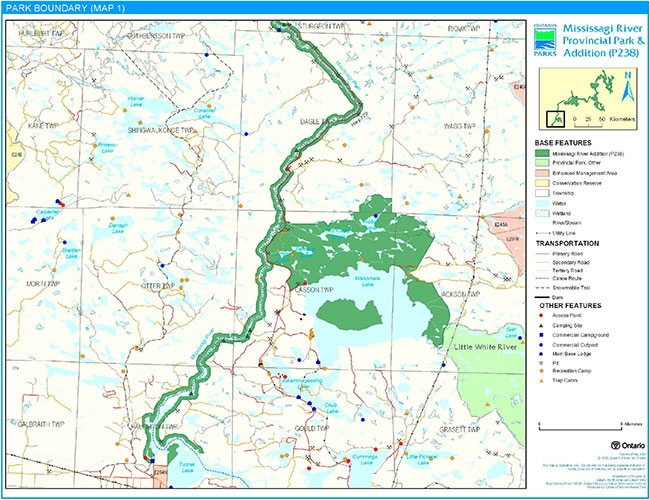

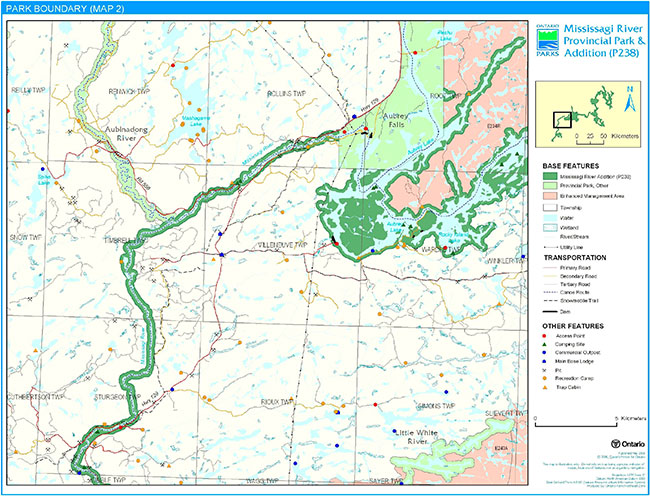

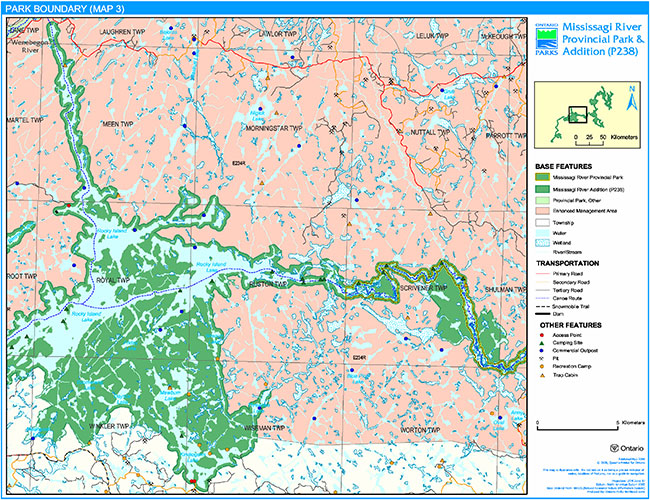

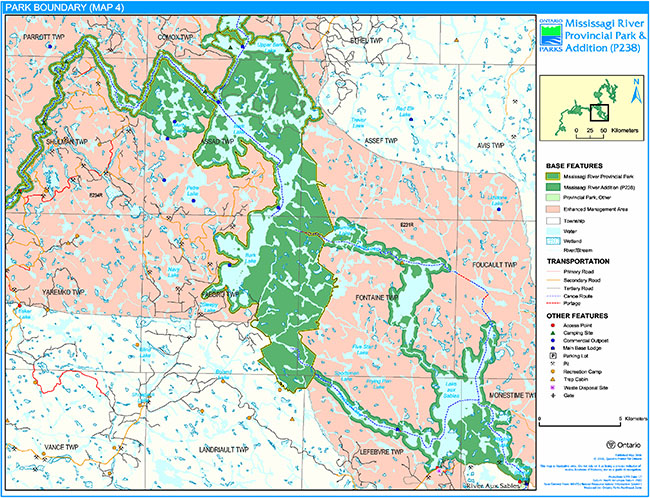

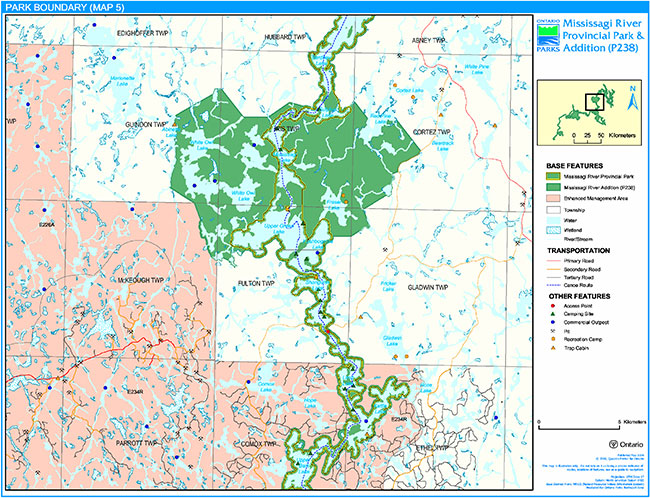

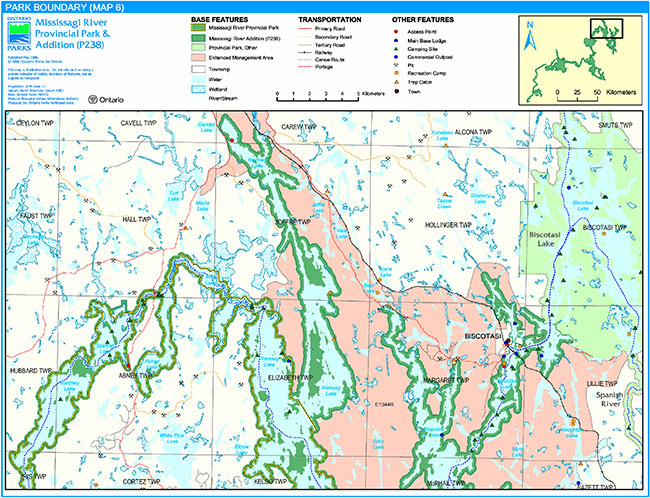

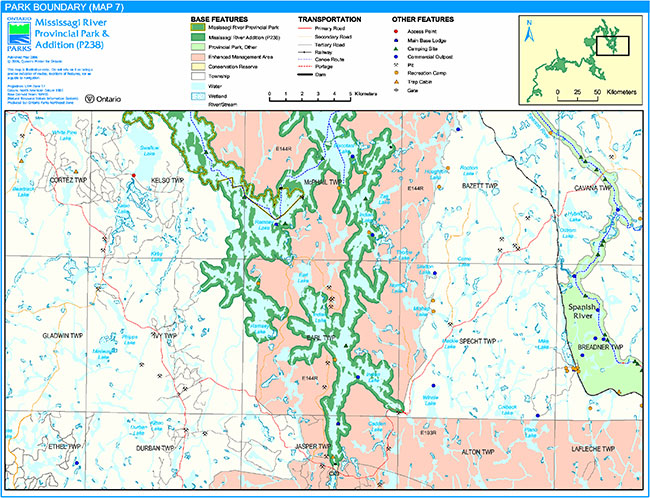

Mississagi River Provincial Park, including the Mississagi River Additions (P238), is located northeast of Espanola, north of Elliot Lake, and south of Sultan (Figure 1). The park is 91,247 hectares in size and stretches over 52 townships (Figures 2a to 2g).

The original park was regulated as a provincial park in 1974 (O. Reg. 451/74). The Mississagi River Additions, regulated as a part of the existing park in May 2003 (O. Reg. 210/03), were identified by Ontario’s Living Legacy Land Use Strategy (OMNR 1999) as an extension to the waterway class park. The purpose of the waterway classification is to protect outstanding recreational water routes and to provide high quality recreational and educational opportunities.

1.1 Objectives

Mississagi River Provincial Park will be managed consistent with the four objectives for provincial parks:

Protection: To protect provincially significant elements of the natural and cultural landscapes of Ontario.

Recreation: To provide provincial park outdoor recreation opportunities ranging from high-intensity day-use to low-intensity wilderness experiences.

Heritage Appreciation: To provide opportunities for exploration and appreciation of the outdoor natural and cultural heritage of Ontario.

Tourism: To provide Ontario’s residents and out-of-province visitors with opportunities to discover and experience the distinctive regions of the Province.

2.0 Management context

The purpose of this Interim Management Statement (IMS) is to provide direction to ensure the custodial management of park resources. Future planning may be undertaken as required to provide direction on significant decisions regarding resource stewardship, development, operations and permitted uses.

Park management will follow direction from:

- Provincial Parks Act (1990) and regulations

- Ontario Provincial Parks Planning and Management Policies (OMNR 1992)

- Ontario’s Living Legacy Land Use Strategy and policy clarifications (OMNR 2000), amendments, and related direction

- Crown Land Use Policy Atlas (OMNR 2004a).

In addressing custodial management obligations to protect park values and ensure public health and safety, Ontario Parks will ensure that policy and Environmental Assessment Act (1990) requirements are implemented.

Figure 1: Regional Context

Enlarge Figure 1: Regional Context

Figure 2a: Park Boundary

Enlarge Figure 2a: Park Boundary

Figure 2b: Park Boundary

Enlarge Figure 2b: Park Boundary

Figure 2c: Park Boundary

Enlarge Figure 2c: Park Boundary

Figure 2d: Park Boundary

Enlarge Figure 2d: Park Boundary

Figure 2e: Park Boundary

Enlarge Figure 2e: Park Boundary

Figure 2f: Park Boundary

Enlarge Figure 2f: Park Boundary

Figure 2g: Park Boundary

Enlarge Figure 2g: Park Boundary

2.1 Environmental assessment

As a part of the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (MNR), Ontario Parks is a public sector agency which is subject to the Environmental Assessment Act. Park management will be carried out in accordance with legislation, policies, and guidelines that are required under A Class Environmental Assessment for Provincial Parks and Conservation Reserves (OMNR 2005).

3.0 Park features and values

Mississagi River Provincial Park is a mostly linear waterway park which consists of a series of interconnecting lakes and river shorelines from Biscotasi and Ramsey lakes to Tunnel Lake. The park boundary is, for the most part, 200 metres from the water’s edge, except for some places where creeks, rivers, natural heritage and road or other arbitrary (i.e., vectored) features delineate the boundary.

3.1 Geological features

Mississagi River Provincial Park is almost entirely within the 2.75 to 2.67 Million years old (Ga) western Abitibi Subprovince, in the Archean Superior Province of the Precambrian shield. Wakomata Lake, near the south end of the park, straddles the northern margin of the Southern Province Paleoproterozoic 2.4 to 2.2 Ga Huronian Supergroup (Frey and Duba 2002).

Bedrock in the park is dominantly Archean granitic batholithic rocks of the Algoma Plutonic Domain of the Ramsey-Algoma granitoid complex, a large area of plutonic and gneissic rocks which was emplaced between 2.70 and 2.68 Ga. The small area of Huronian Supergroup metasedimentary rocks contains feldspathic sandstones and conglomerate of the Gowganda and Lorrain formations of the Cobalt Group (Frey and Duba 2002).

The surficial deposits of the park are thin, sandy ground moraine till, deposited approximately 11,000 years ago (11 ka) by the south-south-westward advancing Superior Lobe of the continental ice sheet, and glaciofiuvial sands, reworked into modern alluvium by the river system from numerous eskers that cross the northeastern part of the park. Most of the park was part of a large island in a succession of proglacial lakes which formed as the ice sheet receded northward, approximately 10 to 9 ka. The Wenebegon River segment of the park occupies the main drainage of glacial Lake Sultan. Metre-high mega-ripple bedding of the jökulhlaup drainage are preserved in gravelly sand on islands in the lower Wenebegon River. The representation of these features contributes the conservation of the Quaternary "Algonquin Stadial" and "Timiscaming Interstadial" environmental themes (Frey and Duba 2002).

Within the Ontario Parks system, the bedrock geology of Mississagi River Provincial Park is regionally significant for its representation of an extensive transect of granitic batholithic rocks of the Algoma Plutonic Domain of the Ramsey-Algoma granitoid complex; its minor representation of components of the Gowganda and Lorrain formations of the Cobalt Group is locally significant. The park is provincially significant in its display of unconsolidated mega-ripple bedding of the jökulhlaup drainage of glacial Lake Sultan (Frey and Duba 2002).

3.2 Biological features

Mississagi River Provincial Park is bisected by the boundary which separates the Boreal Forest Region in the north and the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Region in the south (Noble 1991b).

The Mississagi River Additions add substantial aquatic, wetland, and terrestrial representations to the existing Mississagi River Provincial Park. This extensive park includes seven different landforms. The principal features of the additions include hydro-managed headwater lakes, riverine and lacustrine wetlands, headwater floating fen complexes, cliffs and rock barrens, and a wide array of forest ecosites which range from young to old-growth. The provincially significant Rocky Island - Kindiogami Forest contains a wide variety of forest types representative of ecodistrict 4E-3, including old growth pine elements which survived the large Mississagi fire of 1948 The White Owl-Red Pine lakes complex was also identified as provincially significant for its diverse representations of aquatic, wetland, and terrestrial representations on four landform types (Morris 2002).

The original Mississagi River Provincial Park exhibits distinct transitional flora, which is to be expected given the length of this park and the fact that the boundary between the Boreal Forest Region and the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Forest Region crosses in the middle. The elements of both regions are well-represented in the area (Noble 1991b).

The park’s linear shape is not conducive to extensive fauna habitat protection; valley corridors have a function as a travelway for animals which follow lake and river shorelines (Noble 1991b). Known nesting locations of Osprey and Bald Eagle occur in the park (Morris 2002).

3.3 Cultural setting

The waterway has a rich heritage, which began centuries ago, with Aboriginal people living on the shores of the Great Lakes and travelling the Mississagi River to hunt and fish. Voyageurs and fur traders with the Northwest Company also paddled these waters. Subsequently, construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) brought trappers, bushmen, and tourists from Biscotasing; the advent of the forest industry brought lumbermen who drove pine logs down the Mississagi River to the town of Blind River. Commercial logging continued in the upper Mississagi watershed despite the Mississagi fire of 1948, which burned over a period of five months and consumed almost 400,000 hectares of forest. While the last log drives ended in the late 1960s, the forest which resulted from the fire is now reaching maturity (Kutas 2005).

In 1912, artist Tom Thomson paddled and painted on the Mississagi River. The river’s reputation has also been associated with Grey Owl, who first came to Biscotasing in 1914 to work as a Fire Ranger along portions of the Mississagi waterway. Today, the primary use of the Mississagi River is for recreational purposes; the river is a popular destination for hunting and fishing, and a canoe route (Kutas 2005)

A cultural resources inventory of the original portion of Mississagi River Provincial Park, conducted in 1991, revealed evidence of human occupation in the area which dated from the period shortly after deglaciation (i.e., Early Archaic) to the present day. Thus, the human use of Mississagi River Provincial Park is estimated to have lasted for at least the last 9,000 years (Adams and Errington n.d.).

3.4 Recreation

The main recreational features of Mississagi River Provincial Park are the river and other waterbodies, developed land trails, accessibility by land, cultural sites, and wildlife and vegetation. Recreational activities available in the park are canoeing, motorboating, fishing, hunting, camping, and cottaging (Kutas 2005).

The Mississagi River is a provincially significant canoe route. Literature on the history of the Mississagi River and area, include the river’s association with Grey Owl, who worked as a Lands and Forests Fire Ranger. Some areas of the park may provide solitude as well as scenic viewscapes of cliffs and wetlands (Kutas 2005).

Motorboating occurs in most areas of the park, except for some portions of the Mississagi River. Angling and hunting are popular activities that will continue throughout the park. Camping occurs throughout the park at existing sites on the river, as well as along the roads leading to the park (Kutas 2005).

4.0 Aboriginal uses

Mississagi River Provincial Park lies within the Robinson Huron Treaty of 1850.

First Nations have expressed interest in and have shared knowledge of the park and surrounding area. Aboriginal communities have used the area for hunting, trapping, fishing, gathering and travel. These uses may continue, subject to public safety, conservation and other considerations.

Any communications and cooperation between Aboriginal communities and the MNR for planning and operations purposes will be done without prejudice to any future discussions or negotiations between the government of Ontario and Aboriginal communities.

5.0 Stewardship policies

The removal, damage or defacing of Crown properties, natural objects, relics, and artefacts is not permitted in provincial parks (Provincial Parks Act).

Non-native species will not be deliberately introduced into the park. Where non-native species are already established and threaten park values (i.e., has become invasive), a strategy to control the species may be developed (OMNR 1992).

5.1 Terrestrial ecosystems

5.1.1 Harvesting

Commercial forest operations are not permitted within the park. The harvest of non-timber forest products such as club moss, Canada yew, etc., will not be permitted within the park (OMNR 1992). Existing authorized wild rice harvesting may continue. New operations will not be permitted. There are no fuelwood cutting permits currently issued for the park. New permits will not be issued (OMNR 2000).

5.1.2 Insects and disease

Insects and diseases may be managed where the aesthetic, cultural, or natural values of the park are threatened. Control measures will follow guidelines established by the Ontario Ministry of the Environment (MOE) and MNR. Whenever possible, biological control measures will be given preference over the use of chemicals (OMNR 1992).

5.1.3 Fire

Mississagi River Provincial Park is located within the Boreal and Great Lakes/St. Lawrence fire management zones. In accordance with existing provincial park policy and the Forest Fire Management Strategy for Ontario (OMNR 2004b), forest fire protection will be carried out in the park as on surrounding lands. Whenever feasible, MNR's Forest Fire Management program will use techniques that minimize damage to the landscape, such as limiting the use of heavy equipment or limiting the number of trees felled during response efforts (OMNR 2004b).

5.1.4 Wildlife management

Mississagi River Provincial Park is located within Wildlife Management Units 36, 37, and 38. The removal or harassment of non-game animals is not permitted (Provincial Parks Act).

Hunting

Sport hunting is permitted to continue. This activity may be subject to conditions identified during future planning (e.g., the designation of restrictive zones). Considerations of safety and conservation with respect to hunting may be made through future planning, which would include public and Aboriginal consultation (OMNR 2000).

The Fish and Wildlife Conservation Act (1997) and the Migratory Birds Convention Act (1994) govern hunting within the park. The Ontario Hunting Regulations Summary contains regulations specific to this area. The harvest of bullfrogs or snapping turtles is illegal in provincial parks.

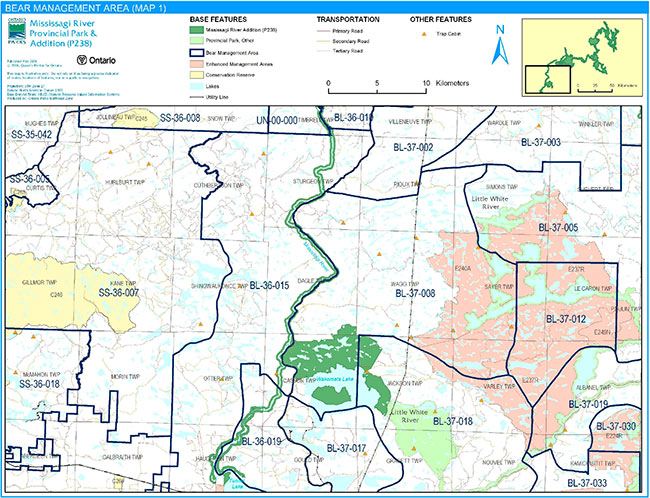

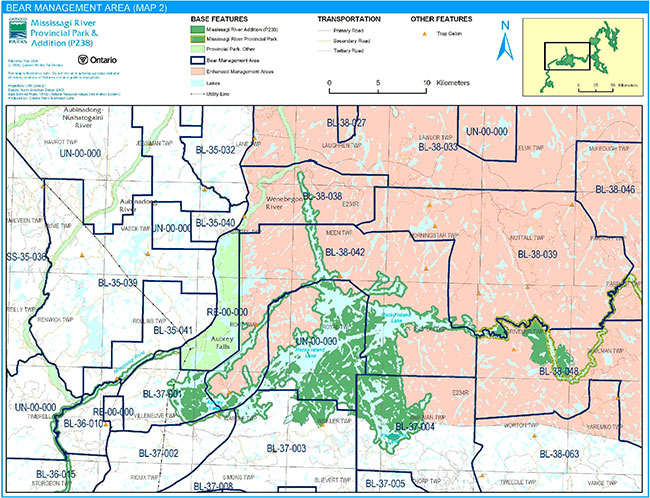

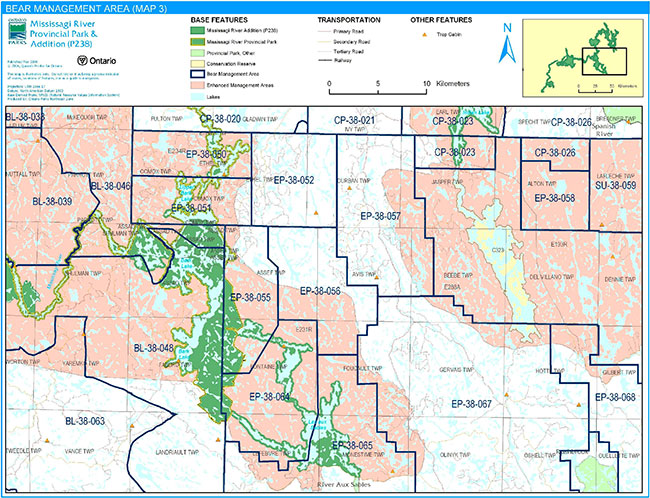

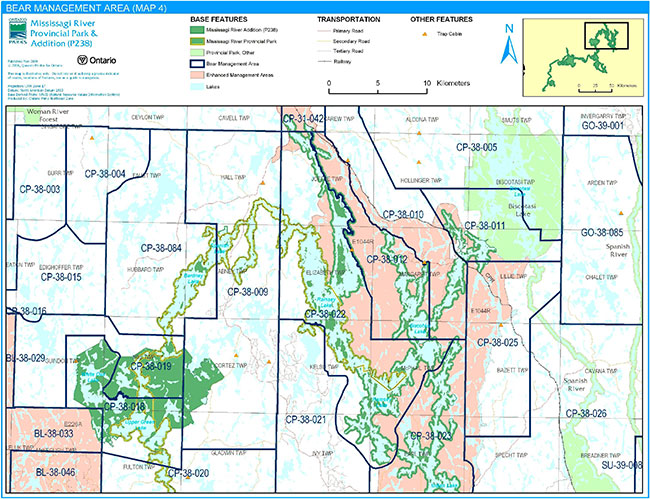

Bear Management Areas

Mississagi River Provincial Park includes portions of approximately 52 bear management areas (Figures 3a to 3d). Existing commercial bear hunting operations are permitted to continue. This activity may be subject to conditions identified during future planning (e.g., the designation of zones). New BMA licences will not be permitted (OMNR 2000; 2003).

Trapping

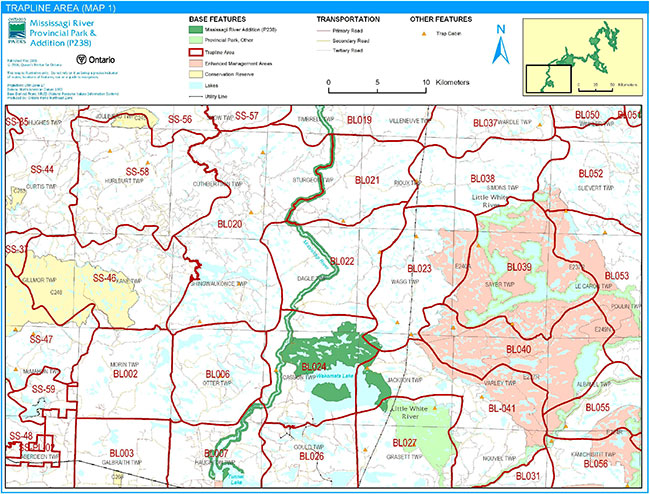

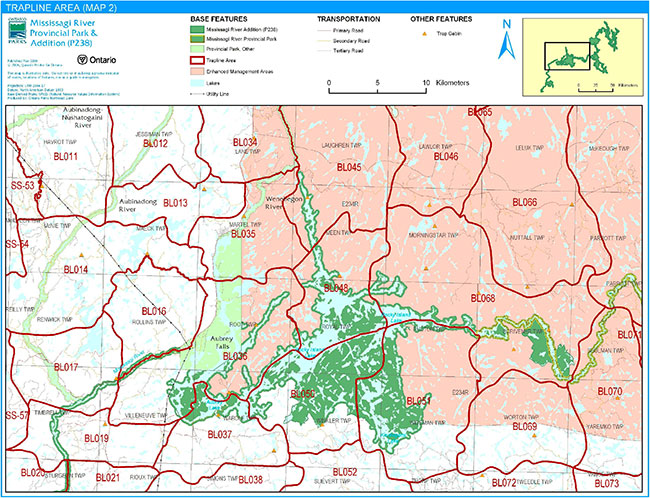

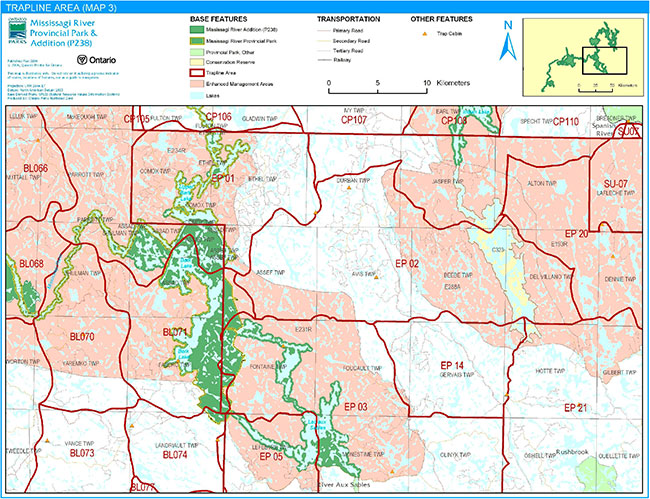

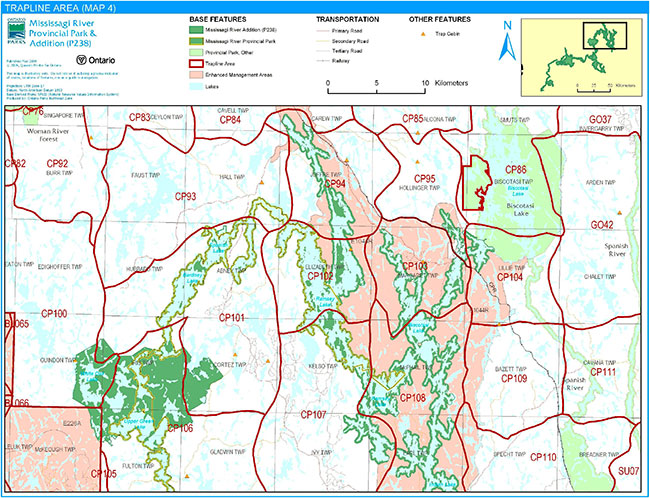

Mississagi River Provincial Park includes portions of approximately 36 trapline areas (Figures 4a to 4d). Approximately 11 trap cabins associated with the traplines are located within the park.

Existing commercial fur harvesting operations may continue where the activity has been licensed or permitted since January 1, 1992. This activity within the original park boundary may be subject to conditions identified during future planning (e.g., the designation of zones). New operations, including trap cabins and trails, will not be permitted (OMNR 2000; 2003). Transfers of active trap line licenses are permitted, subject to a review of potential impacts and the normal transfer or renewal conditions that apply.

5.1.5 Adjacent land

Forestry

The land adjacent to the park is within the Spanish Forest (#210) and Northshore Forest (#680) management units. Both forest management plans are scheduled to be reviewed in 2010 (OMNR 2006).

Provincial parks

Four provincial parks and one signature site abut Mississagi River Provincial Park: Aubrey Falls, River Aux Sables, Little White River, and Aubinadong River provincial parks and the Spanish River Valley Minitegozibe Signature Site.

Aubrey Falls Provincial Park (P1873): Aubrey Falls Provincial Park, a non-operating park, protects an impressive waterfall on the Mississagi River. Regulated as a provincial park in 1985, the 4,860-hectare park provides boating, canoeing, fishing, hiking and other recreational opportunities. The park also contains water control structures for hydro-electricity generation.

Figure 3a: Bear Management Areas

Enlarge Figure 3a: Bear Management Areas

Figure 3b: Bear Management Areas

Enlarge Figure 3b: Bear Management Areas

Figure 3c: Bear Management Areas

Enlarge Figure 3c: Bear Management Areas

Figure 3d: Bear Management Areas

Enlarge Figure 3d: Bear Management Areas

Figure 4a: Trapline Areas

Enlarge Figure 4a: Trapline Areas

Figure 4b: Trapline Areas

Enlarge Figure 4b: Trapline Areas

Figure 4c: Trapline Areas

Enlarge Figure 4c: Trapline Areas

Figure 4d: Trapline Areas

Enlarge Figure 4d: Trapline Areas

River Aux Sables Provincial Park (P228): This 3,658-hectare park encompasses the River aux Sables, which originates at Lac aux Sables and flows for 85 kilometres to the south, to Chutes Provincial Park. The park provides accessible canoeing opportunities; the southern portion of the river is nationally renowned for whitewater kayaking. River Aux Sables Provincial Park also includes the aux Sables East natural heritage area, a forest of old cedar and pine growing on a flat lacustrine deposit which was once the bed of an ancient lake.

Little White River Provincial Park (P261): Little White River Provincial Park, which is 12,782 hectares in size, was regulated as a provincial park on December 7, 2002. The park includes an approximately 100-kilometre stretch of the Little White River, which spans from the Blue Lake headwater area to the Mississagi River in the south. The river’s meanders, rapids, and gravel flats pass through forests and shoreline habitats such as wetlands, oxbow sloughs, and floodplain swamps of silver maple, black ash and white elm. The Raven Lake natural heritage area within the park contains bedrock cliff faces, upland rock barrens, deep gorges, ravines, convoluted linear wetlands, and significant stands of white pine growing on glacier-scoured hills.

Aubinadong River Provincial Park (P319): Aubinadong River Provincial Park, which is 2,722 hectares in size, protects a diverse landscape. The river valley changes from a rugged environment dominated by high rock faces in the northern portion, to gentler, low-lying topography near its confluence with the Mississagi River Provincial Park in the south. The river is a series of wide, slow-moving stretches which are connected by narrow channels of fast-moving water. While most of the forest is second-growth as a result of the Mississagi fire of 1948, White Pine can be found along the corridor. The Aubinadong River is a cold water (trout) system.

Spanish River Valley Minitegozibe Signature Site: Signature sites are distinctive geographic areas which showcase Ontario’s natural and cultural heritage features. Spanish River Valley Minitegozibe Signature Site is composed of: Biscotasi Lake Provincial Park (P1572), Spanish River Provincial Park (P192), Sinaminda and Kennedy Lake Area Enhanced Management Area (EMA) (E193R), Acheson Lake EMA (E204A), and Ishpodnok (formerly Swann Lake) EMA (E217A). The signature site, which is approximately 98,634 hectares in size, protects outstanding scenery, waterways, historical sites, and wildlife habitat of the Spanish River valley. The signature site provides many tourism and recreational opportunities, while also providing for sustainable resource management activities in the enhanced management areas.

Conservation Reserves

The conservation reserve network complements the provincial park system by protecting representative natural areas and special landscapes. Two conservation reserves are located near Mississagi River Provincial Park: Wagong Lake Forest and Mozhabong Lake conservation reserves.

Wagong Lake Forest Conservation Reserve (C243): This 2,381-hectare conservation reserve protects forests which are dominated by Jack pine, trembling aspen, and black spruce, including some older stands of these forest types. Wagong Lake Forest Conservation Reserve also contains white birch stands and a small, old-growth red pine stand on the eastern shore of Wagong Lake. This site contains the best known example of this type of vegetation on a low sand and gravel hills (glacial outwash) landform in Ecodistrict 4E-3.

Mozhabong Lake Conservation Reserve (C323): The Mozhabong Lake Conservation Reserve boundary is a 120-metre wide area around Mozhabong Lake, as well as the interior islands and peninsulas, which totals 4,354 hectares. This is located between the large Sinaminda and Kennedy Lake Area EMA (E193R) to the east and the smaller Mozhabong Lake Access EMA (E288A) to the west. Mozhabong Lake is a self-sustaining trout lake which is part of a tributary watershed within the Spanish River Basin. Fishing, boating and hunting are popular recreational activities. Despite there being a well-used access point on the south end of the lake and several recreation camps scattered on its shoreline, the area provides a relatively remote experience.

Enhanced Management Areas

Enhanced management areas are a fairly new land use category which has been established to provide more detailed land use direction in areas of special features and values. A wide variety of resource and recreational uses may occur in enhanced management areas. Mississagi River Provincial Park abuts five enhanced management areas: Biscotasi Lake, Mozhabong Lake Access, Lac Aux Sables, Rocky Island Lake / Mississagi River Area, Bridgeland Spillway, and North Hinkler Road Area enhanced management areas.

Biscotasi Lake Enhanced Management Area (E1044R): This 31,096-hectare area encompasses those parts of the Ramsey Lake and Biscotasi Lake basins which are not included in the Mississagi River Provincial Park and Biscotasi Lake Provincial Park (P1572). Biscotasi Lake Enhanced Management Area surrounds the town of Biscotasing and provides many recreational and tourism opportunities. Other major values are forestry resources, mineral potential, and a water storage reservoir system that developed by INCO Ltd. for hydraulic generating stations downstream on the Spanish River system. The land use intent of the site is to assist in the economic development of Biscotasing by reinforcing the townsite as a principal access point for Biscotasi Lake.

Mozhabong Lake Access Enhanced Management Area (E288A): This enhanced management areas, which is 19,680 hectares in size, surrounds the Mozhaboing Lake Conservation Reserve (C323). Mozhabong Lake Access Enhanced Management Area is an important recreational and forestry area which is relatively remote but which contains road-accessible areas. This area provides high-quality remote recreational experiences, including hunting, fishing, canoeing, and camping.

Lac Aux Sables Enhanced Management Area (E231R): Lac Aux Sables Enhanced Management Area protects a high-quality recreational landscape surrounding Lac Aux Sable and Big Trout Lake, the latter of which is considered to be a provincially significant coldwater lake. The 25,477- hectare area also includes the Sable - Bark Lake Canoe Route. Designated for low-density, limited-road-access recreational use, the enhanced management area also encompasses four high-quality sport fishing lakes, several private recreation camps, outpost camps, and a main base lodge. Traditional uses of the area include commercial bear hunting, moose hunting, snowmobiling, and fishing. This is also an important area for forestry.

Rocky Island Lake / Mississagi River Area (E234R): This large, 111,717 hectare enhanced management area encompasses the Mississagi River watershed and Rocky Island Lake. This area supports a significant fly-in tourism industry and important forestry operations. Although forestry operations have accessed the central portion of the area, there sizable remote pockets remain, the largest of which is to the north of the Hinkler Road. In the portion to the south of the Mississagi River, forest management and Crown land recreation are the major uses. Scattered throughout the enhanced management area are a wide variety of developments and other uses including outpost camps, cottages, canoe routes, and angling and hunting areas. North of the Mississagi River, the area is heavily developed for tourism purposes.

Bridgeland Spillway (E264N): The 1,180-hectare Bridgewater Spillway Enhanced Management Area is a spectacular landscape which is rich in glacial history. Now the Little Thessalon River valley, there was once a great channel of glacial meltwater which flowed southward through the region from ancient lakes. The meltwater scoured the land and the lake levels left tell-tale marks in the landforms. Glacial features include abandoned waterfalls and tracts of land called scablands, features where sand and gravel had been washed away by powerful meltwater flows. The abandoned river channels now support swamps and bogs.

North Hinkler Road Area (E266A): North Hinkler Road Area Enhanced Management Area is 58,190 hectares in size. This area is managed for remote tourism, remote recreation, and resource extraction.

5.1.6 Land disposition

New land disposition for the private use of individuals or corporations will not be permitted (OMNR 1992; 2000). Within the pre-OLL portion of Mississagi River Provincial Park, all forms of existing tenure issued by the Crown for private use (i.e., land use permits, licences of occupation, and leases) will be phased out by January 1, 2010 (OMNR 1992).

Land Use Permits, Licenses of occupation, and unauthorized occupations

Approximately nine land use permits (LUP) are located within the park.

Existing authorized LUPs within the Mississagi River Additions may be eligible for enhanced tenure but not the purchase of land. Recreational camp LUPs cannot be changed to commercial LUPs unless this is supported during a review as part of future planning. Enhanced tenure is defined as a possible extension of the term of the LUP for up to 10 years or upgrade in tenure (i.e. LUP to lease) (OMNR 2000a).

Enhanced tenure for an LUP is not guaranteed. Requests for enhanced tenure or to transfer LUPs will be reviewed based upon the following criteria:

- Continued compliance with the conditions of the LUPs

- Current land disposition policies for LUPs

- Consistency with park objectives to sustain values – no effects on heritage values and/or conflict with other uses

- Consistency with Aboriginal land claim negotiations or protocol agreements

- All rents, taxes, fees, rates, or charges are paid and in good standing

An extension in the term of tenure for an existing LUP does not convey a commitment to provide for a change in the type or the standard of existing access to the private recreation camp.

There are no licenses of occupation in Mississagi River Provincial Park.

There may be unauthorized occupations within the park; these will be dealt with by enforcement officers. New unauthorized occupations will be dealt with as they are discovered.

Flooding rights

Brookfield Power holds the flooding rights for Mississagi River Provincial Park. The authorities for the flooding rights are: Licence of Occupation 7198 for Rocky Island Lake; Water Power Lease Agreement 94 for Aubrey Lake and parts of the Mississagi River for the Aubrey Generating Station; Water Power Lease Agreement 35 for Tunnel Lake and parts of the Mississagi River for the Rayner Generating Station; and Water Power Lease Agreement 100, also for Tunnel Lake and parts of the Mississagi River, for the Wells Generating Station.

Patent land

Mississagi River Provincial Park is mostly surrounded by Crown Land, with mining lands adjacent to the park in some places. The park also abuts and surrounds parcels of patent land. Private land is not included within the park boundary and, as such, park policy does not apply to these areas.

Boat caches

There are no authorized boat caches within Mississagi River Provincial Park. Boats are not permitted to be left unattended in the park without written permission from the superintendent under the authority of the Provincial Parks Act.

5.1.7 Industrial uses

Aggregate: There are 17 known aggregate pits (active or inactive) located within the boundary of Mississagi River Provincial Park. Aggregate extractions authorized by the Aggregate Resources Act on the date of approval of this IMS are allowed to continue. As the site limits are worked, there will be progressive or sequential restoration of the pits to allow the site to return to a natural condition (e.g. slope stabilization, native species plantings, etc.).

There may be parties interested in processing an application(s) for an aggregate permit/licence in Mississagi River Provincial Park. The Aggregate Resources Act does not exempt or supersede other legislative or regulatory requirements such as the Environmental Assessment Act or the Provincial Parks Act and associated regulations. There is a legal obligation that these requirements must be met before an application for an aggregate permit/licence can proceed or be processed in a provincial park.

Specific to Crown land set aside and regulated under the Provincial Parks Act and the Crown’s legal obligations under the Environmental Assessment Act, the need for additional aggregates to be sourced in Mississagi River Provincial Park must be addressed as a policy statement in a management plan developed through public consultation and a regulation under the Provincial Parks Act. Mississagi River Provincial Park does not have a management plan developed through public consultation nor a regulation under the Provincial Parks Act. As such an application for an additional aggregate authorization(s) under the Aggregate Resources Act cannot proceed or be processed for sites within Mississagi River Provincial Park.

The Provincial Park and Conservation Reserves Act received Royal Assent on June 20, 2006 and is pending proclamation. Once the Act is proclaimed aggregate extraction in Mississagi River Provincial Park will not be permitted except for aggregate pits that are authorized under the Aggregate Resources Act on the day the Act is proclaimed. No additional authorizations will be permitted in the park after the proclamation of the Provincial Park and Conservation Reserve Act.

Mineral Exploration and Mining: There are no existing mining claims within the park. Mineral exploration and mining are not permitted within the park. The mining and surface rights on all lands within the park have been withdrawn from staking under the Mining Act (1990). In accordance with Ontario’s Living Legacy Land Use Strategy, however, access in the park to mining lands (i.e., forest reserve(s) and mining patents) will be permitted for purposes of mineral exploration, development, or operations. Access will be planned in accordance with Environmental Assessment Act requirements.

5.1.8 Access and crossings

Access

Mississagi River Provincial Park is accessible by land, water, and air.

There are several roads which provide access to the park, including new and abandoned forestry roads. The rivers and headwaters within the park are now primarily used as water routes for canoeing and motor boat use (Kutas 2005). Some lakes in the park are accessible by floatplane.

Roads

The Highway 129 corridor, from Thessalon to Aubrey Falls, travels along or near Mississagi River Provincial Park. There are several roads which branch off of the Highway 129 corridor which provide access to the park. Some of these roads are cottage-access roads (e.g., Peshu Lake Rd) but most are logging roads (e.g., West Branch Road, Bear Track Road). A small portion of Highway 556 follows the Mississagi River to the Aubinadong River. There is also road access to the park from Bisco Road, the travel route to the town of Biscotasing. As a result of the highways, forestry roads, and cottage-access roads, a variety of access points have been created throughout the park (Kutas 2005).

Where existing forest and/or tertiary access roads are essential for continued access beyond the park for forest management, access to in-holdings (e.g., LUPs) or recreational purposes, and alternative road access does not exist, or road relocation is not feasible, existing roads will continue to be available for access. Continued use will include maintenance and may include upgrades (OMNR 2004a). Ontario Parks is not responsible for the maintenance or upgrade of any roads within the park boundary.

Any proposed development, maintenance or upgrading of existing roads must meet all Environmental Assessment Act requirements.

Utility corridors

A hydro line corridor crosses the park in Villeneuve Township. This corridor is included in the park boundary. This corridor is managed through a province-wide LUP issued to Hydro One.

Maintenance of the utility lines must adhere to the regulations set out under the relevant acts, such as the Environmental Assessment Act, the Canadian Environmental Protection Act (1999), and the Pesticides Act (1990). Maintenance activities will not impact negatively on the features and values being protected within the park additions.

All public utilities (e.g., gas pipelines, transmission lines, communications towers) must avoid park lands wherever possible. New utility corridor crossings may be necessary to maintain essential public services (OMNR 2004a).

Any future utility corridors proposed through the park, where park lands are unavoidable, will be reviewed on a case-by-case basis. Protection of park features and values will be priority and all requirements of the Environmental Assessment Act will be met.

Railway

A Canadian Pacific Railway line passes through the northern portion of the park. This railway line is excluded from the park boundary.

Recreational trails

New trails (e.g., hiking) may be developed if the need arises. Any proposed development within the park is subject to Environmental Assessment Act requirements.

Canoe Routes: The Mississagi River is a well-known canoe route. The two canoe routes, as well as other lakes and wetlands, provide an array of paddling options.

Hiking Trails: Informal trails occur in the park. This use will be reviewed during future planning.

Snowmobile Trails: Three authorized snowmobile trails cross the park: TOP trail F and trunk trails D106 and D104 (Kutas 2005). Snowmobile use on existing routes for access to private land in-holdings, LUPs, and recreational ice fishing may continue unless park values are threatened.

All-Terrain Vehicle Trails: There are no authorized ATV trails within the park boundary; however, there is some existing unauthorized ATV use on forest and tertiary access roads within the park. Existing use of these roads to access LUPs is permitted to continue unless this use threatens park values. ATV use may be authorized on old forest access and tertiary roads; this use will be reviewed during future planning. Off-trail ATV use is not permitted (OMNR 2000).

5.2 Aquatic ecosystems

Sustaining quality water resources is integral to the protection of park and adjacent land values. The MOE enforces applicable legislation and regulations for water quality.

5.2.1 Water management

The dams in Villeneuve, Wardle, and Royal townships are part of the Licence of Occupation and Water Power Lease Agreements belonging to Brookfield Power. The dams in McPhail and Jasper townships belong to INCO for downstream hydro-generation.

New commercial hydroelectric developments will not be permitted (OMNR 2000).

Fisheries management

Fisheries management will complement the maintenance and enhancement of native, self-sustaining fish populations (OMNR 1992).

Sport fishing

Sport fishing is permitted within the park. This activity is governed by legislation and regulations in the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Act and the Fisheries Act (1985). The Recreational Fishing Regulations Summary contains details on the applicable regulations for this area.

Commercial baitfish harvesting

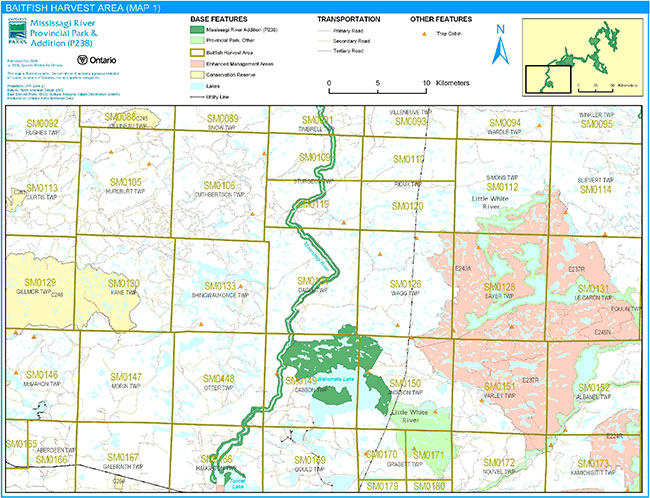

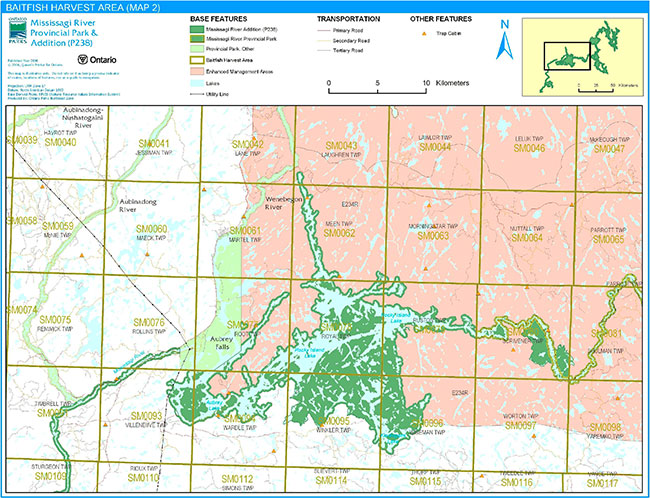

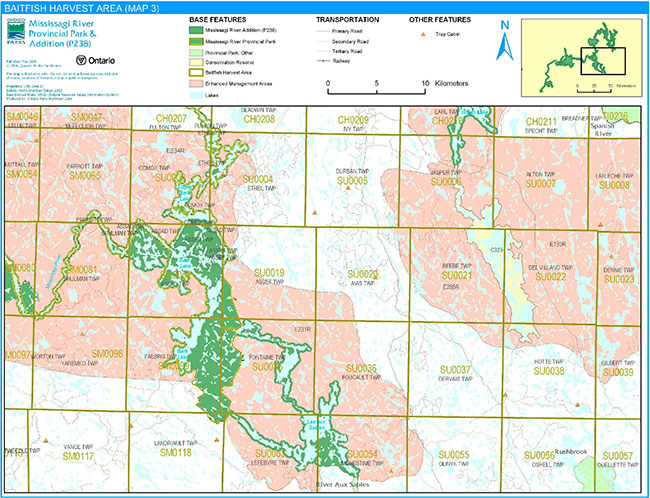

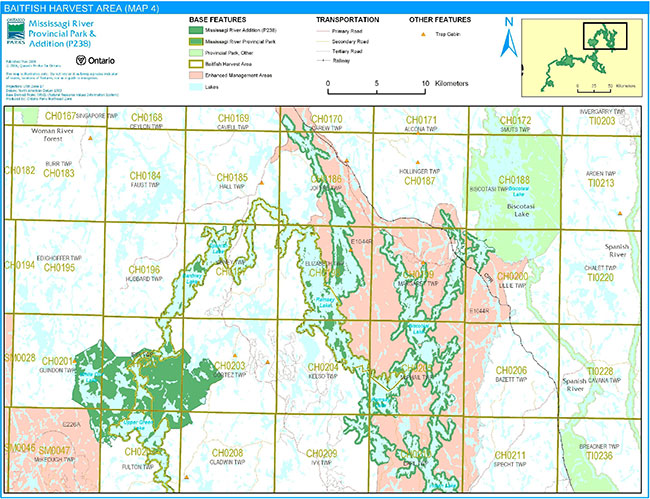

Mississagi River Provincial Park contains portions of approximately 52 baitfish harvesting areas (Figures 5a to 5d).

Existing commercial baitfish harvesting may continue where the activity has been licensed or permitted since January 1, 1992. This activity may be subject to conditions identified through future planning (e.g., the designation of restrictive zones). New baitfish licenses will not be permitted (OMNR 2000; 2003).

Fish stocking

The stocking of native fish species may be considered through future planning, with full public and Aboriginal consultation. Non-native fish species will not be deliberately introduced into park waters (OMNR 1992).

Figure 5a: Baitfish Harvesting Area

Enlarge Figure 5a: Baitfish Harvesting Area

Figure 5b: Baitfish Harvesting Area

Enlarge Figure 5b: Baitfish Harvesting Area

Figure 5c: Baitfish Harvesting Area

Enlarge Figure 5c: Baitfish Harvesting Area

Figure 5d: Baitfish Harvesting Area

Enlarge Figure 5d: Baitfish Harvesting Area

6.0 Operations policies

6.1 Recreation management

Future planning, with full public consultation, will review direction on motorized and non-motorized recreation uses.

6.1.1 Motorized recreation

Motorboats

The use of motorboats is permitted to continue, unless park values are being threatened (OMNR 2004a).

Aircraft

Aircraft landings may be permitted within this waterway park (OMNR 2004a). All aircraft landings are subject to regulation and valid aircraft landing permits issued by the park superintendent under the authority of the Provincial Parks Act.

Snowmobiles

Three authorized snowmobile trails pass through Mississagi River Provincial Park. Snowmobile use on established routes for access to private land in-holdings, LUPs, and recreational ice fishing may continue unless park values are threatened. Off-trail snowmobile use is not permitted within the park. Proposals for new snowmobile trails may be considered though future planning with Aboriginal dialogue and public consultation (OMNR 2000).

All-Terrain Vehicles

There are no authorized ATV trails within the park boundary. The existing use of forest and tertiary access roads to access LUPs is permitted continue unless this use threatens park values. ATV use may be permitted on old forest access and tertiary roads. Off-road use of all terrain vehicles will not be permitted within the park. Proposals for new trails may only be considered through future planning with Aboriginal dialogue and public consultation (OMNR 2000).

6.1.2 Non-motorized recreation

Camping

There are no managed campsites in Mississagi River Provincial Park; there are approximately 89 unmanaged, established campsites in the park.

Ontario Parks may assess the condition of existing campsites and will maintain, rehabilitate, or close sites as required. If there is an identified need, new campsites may be considered (OMNR 2004a). Infrastructure will be permitted in order to protect park features and values in response to use, environmental deterioration and environmental protection requirements. Any proposed development in the park must fulfill the requirements of the Environmental Assessment Act.

Hiking

There are no authorized hiking trails within the boundaries of this provincial park. Many informal trails exist within the park; these trails will be reviewed during future planning. If there is an identified need, the development of new hiking trails may be considered. Trail infrastructure to protect park values and features will be permitted. Any proposed development within the park is subject to Environmental Assessment Act requirements.

Canoeing/kayaking

The canoe routes and portages within Mississagi River Provincial Park are currently unmanaged. Existing uses may continue, unless park values are threatened (OMNR 2004a). Infrastructure to protect park features and values may be permitted and developed in response to use, environmental deterioration and environmental protection requirements.

6.1.3 Emerging recreational uses

There are emerging recreational uses for which there is limited or no policy to deal with their management (e.g., adventure racing and geocaching). The park superintendent will use legislation, policy, and guidelines which are in place to manage emerging uses in the interim.

6.2 Development

There are no existing developments within Mississagi River Provincial Park. Infrastructure to protect park features and values may be permitted and developed in response to use, environmental deterioration, and environmental protection requirements. Any proposed development within the park is subject to the Environmental Assessment Act.

6.3 Commercial tourism

New commercial tourism facilities may be considered where they would be consistent with park policy (OMNR 2004a). Any development must meet the requirements of the Environmental Assessment Act. Existing authorized tourism facilities may continue subject to management prescriptions determined through future planning. Existing tourism facilities (e.g., LUPs, leases) may be eligible for enhanced tenure, and decisions will be made in future planning.

7.0 Cultural resources

A cultural resources inventory of the original Mississagi River Provincial Park revealed evidence of human occupation in the area which dated from the period shortly after deglaciation (i.e., Early Archaic) to the present day (Adams and Errington 1991). The river’s reputation has also been associated with the early years of Grey Owl and the paintings of Tom Thomson (Kutas 2005).

An assessment of the cultural resources specific to the Mississagi River Additions has not yet been completed. The management of any cultural values within this park will be directed toward protection and heritage appreciation (OMNR 1992).

8.0 Heritage education

Literature and other supporting information may be developed to describe the park in the context of Ontario’s provincial park system. Boundary limits, significant heritage features and permitted uses of the waterway may be included in park literature.

Prospective park visitors may be informed about the sensitivity and significance of park values through park literature.

9.0 Research

Scientific research by qualified individuals which contributes to the knowledge of natural or cultural history, or to environmental or recreational management, may be encouraged in the park. Ontario Parks will encourage institutions, such as universities, to undertake research projects.

All research programs will require the approval of Ontario Parks and are subject to park policy and other applicable legislation. Any materials removed from the park will remain the property of Ontario Parks.

Approved research activities and facilities will be compatible with the park’s protection objective. Any site which is affected by research will be rehabilitated as closely as possible to its original state. Environmental Assessment Act requirements will apply.

10.0 References

Adams, N.R., and S.H. Errington, 1991. Cultural Resources Inventory: Mississagi River Provincial Park.

Aggregate Resources Act, 1990.

Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999.

Davidson, R.J., 1981. A Framework for the Conservation of Ontario’s Earth Science Features.

Environmental Assessment Act, 1990.

Fish and Wildlife Conservation Act, 1997.

Fisheries Act, 1985.

Frey, E., and D. Duba, 2002. Earth Science Inventory Checklist: Mississagi River Additions Provincial Park (P238).

Kutus, B., 2005. Recreation Assessment: Mississagi River Provincial Park Additions (P238) Recreation Inventory Report – Version 1.1. Draft.

Migratory Birds Convention Act, 1994.

Mining Act, 1990.

Morris, E.R., 2002. Natural Heritage Area – Life Science Checksheet: Mississagi River Additions (OLL P238). Revised version.

Noble, T.W., 1991a. Earth Science Inventory: Mississagi River Provincial Park.

Noble, T.W. 1991b. Life Science Inventory: Mississagi River Provincial Park.

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, 1974. A Topical Organization of Ontario History. Historic Sites Branch Division of Parks.

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, 1992. Ontario Provincial Parks Planning and Management Policies. 1992 Update.

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, 1999. Ontario’s Living Legacy Land Use Strategy. July 1999. Queen’s Printer for Ontario.

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, 2000. Ontario’s Living Legacy Land Use Strategy (Policy Clarification).

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (OMNR), 2003. Directions for Commercial Resource Use Activities in Provincial Parks and Conservation Reserves. 5 pp.

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, 2004a. Crown Land Use Policy Atlas.

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, 2004b. Forest Fire Management Strategy for Ontario.

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, 2005. A Class Environmental Assessment for Provincial Parks and Conservation Reserves.

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, 2006. List of Forest Management Units (MU) in Ontario (2006-2007). Online. Accessed February 17, 2007.http://ontariosforests.mnr.gov.on.ca/spectrasites/Viewers/showArticle.cfm?id=C74F77D4-68C7- 41A6 8D96FB6079073782&method=DISPLAYFULLNOBARNOTITLE_R&ObjectID=C74F77D4-68C7-41A6-8D96FB6079073782&lang=FR&lang=EN&lang=FR&lang=EN (link no longer active)

Pesticides Act, 1990.

Provincial Parks Act, 1990.

Provincial Parks and Conservation Reserves Act, 2006.

11.0 Appendix A: background information

| Name | Mississagi River Provincial Park (P238e/P238) |

|---|---|

| Classification | Waterway |

| Ecoregion/Ecodistrict | 4E / 4E3 |

| OMNR Administrative Region/District | Northeast Region – Chapleau and Sault Ste. Marie |

| Total Area (ha) | 91,247 |

| Regulation Date and Number | May 2003 (O. Reg. 210/03) |

Representation

Earth Science:

Mississagi River Provincial Park is almost entirely within the 2.75 to 2.67 Million years old (Ga) western Abitibi Subprovince, in the Archean Superior Province of the Precambrian shield. The Wakomata Lake nodal area, near the south end of the park, straddles the northern margin of the Southern Province Paleoproterozoic 2.4 to 2.2 Ga Huronian Supergroup (Frey and Duba 2002).

The Abitibi Subprovince is one of many elongated orogenic terranes (subprovinces) of distinctive structure and metamorphosed volcanic, sedimentary, and plutonic rock assemblages which accreted southward in the early Precambrian. The Huronian Supergroup of the eastern Southern Province consists of four stratigraphic groups of metasedimentary and minor metavolcanic and intrusive rocks (Frey and Duba 2002).

These geological environments are part of the modern organization of the complex products of late Archean orogenic events in the Superior Province and early Proterozoic sedimentary cycles in the Southern Province. As such, their representation in Mississagi River Additions Provincial Park contributes to the conservation of the "Early Archean Basement", "Late Archean Volcanic Islands and Sedimentary Basins" and "Early Aphebian Huronian Stable Platform" Precambrian environment themes (Frey and Duba 2002).

Bedrock in the park is dominantly Archean granitic batholithic rocks of the Algoma Plutonic Domain of the Ramsey-Algoma granitoid complex, a large area of plutonic and gneissic rocks that was emplaced between approximately 2.70 and 2.68 Ga. The small area of Huronian Supergroup metasedimentary rocks contains feldspathic sandstones and conglomerate of the Gowganda and Lorrain formations of the Cobalt Group (Frey and Duba 2002).

The surficial deposits of the park are thin, sandy ground moraine till, deposited approximately 11,000 years ago (11 ka) by the south-south-westward advancing Superior Lobe of the continental ice sheet, and glaciofiuvial sands, reworked into modern alluvium by the river system from numerous eskers that cross the northeastern part of the park. Most of the park was part of a large island in a succession of proglacial lakes which formed as the ice sheet receded northward, approximately 10 to 9 ka. The Wenebegon River segment of the park occupies the main drainage of glacial Lake Sultan. Metre-high mega-ripple bedding of the jökulhlaup drainage are preserved in gravelly sand on islands in the lower Wenebegon River. The representation of these features contributes the conservation of the Quaternary "Algonquin Stadial" and "Timiscaming Interstadial" environmental themes (Frey and Duba 2002).

Within the Ontario Parks system, the bedrock geology of Mississagi River Provincial Park is regionally significant for its representation of an extensive transect of granitic batholithic rocks of the Algoma Plutonic Domain of the Ramsey-Algoma granitoid complex; its minor representation of components of the Gowganda and Lorrain formations of the Cobalt Group is locally significant. The park is provincially significant in its display of unconsolidated mega-ripple bedding of the jökulhlaup drainage of glacial Lake Sultan (Frey and Duba 2002).

Although they are common, abundant throughout most of the park, and resistant to most human activities, the bedrock exposures of Mississagi River Provincial Park are susceptible to graffiti, uncontrolled sampling, and unplanned disturbances. The areas of unconsolidated Quaternary ego-ripples are small and sensitive to disturbances such as campsite use, aggregate extraction, and any higher level flooding of Aubrey Lake (Frey and Duba 2002).

A flooding limit adequate to ensure continued exposure of the areas of mega-ripples should be secured with the operator of Aubrey Falls dam. Identifying signage at the site or an island-specific camping prohibition would risk vandalism or destruction of the unconsolidated bedforms. Instead, camping should be prohibited on all islands in Aubrey Lake (Frey and Duba 2002).

Life science:

Mississagi River Provincial Park is bisected by the boundary which separates the Boreal Forest Region in the north and the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Region in the south. This section of the Boreal Forest is characterized by such species as black spruce (Picea mariana) and white spruce (Picea glauca), balsam fir (Abies balsamea), larch (Larix laricina), Jack pine (Pinus banksiana), trembling aspen (Populu tremuloides) and white birch (Betula papyrifera), and balsam poplar (Populous balsamifera). The Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Forest Region is a transitional belt of mixed hardwood-coniferouis forest which consists of White (Pinus strobus) and Red Pine (Pinus resinosa), eastern hemlock (Tsuga Canadensis), yellow birch (Betula alleghaniensis), sugar maple (Acer saccharum), red maple (Acer rubrum), red oak (Quercus rubra), basswood (Tilia americana), white elm (Ulmus Americana), white cedar (Thuja occidentalis), largetooth aspen (Populus grandidentata), beech (Fagus grandifolia), white oak (Quercus alba), butternut (Juglans cinerea), and white ash (Fraxinus americana) (Noble 1991b).

The Mississagi River Additions add substantial aquatic, wetland, and terrestrial representations to the existing Mississagi River Provincial Park. This extensive park includes seven different landforms. The principal features of the additions include hydro-managed headwater lakes, riverine and lacustrine wetlands, headwater floating fen complexes, cliffs and rock barrens, and a wide array of forest ecosites which range from young to old-growth. The provincially significant Rocky Island - Kindiogami Forest contains a wide variety of forest types representative of ecodistrict 4E-3, including oldgrowth pine elements which survived the large Mississagi Fire of 1948. The White Owl-Red Pine Lakes complex was also identified as provincially significant for its diverse representations of aquatic, wetland, and terrestrial representations on four landform types (Morris 2002).

Upland Boreal communities are found throughout the river corridor in the original park, but Great Lakes-St. Lawrence species such as Red and White Pine do not form communities, other than scattered small groves, north of the watershed divide between the Mississagi River in the south and the Spanish River to the north. Only south of the dived do Red and White Pine become apparent. The more southerly shrub species and chokeberry (Aronia melanocarpa) were noted south of the divide but are common only south of Upper Bark Lake. Black ash was observed in the Upper Bark Lake Area and occurred sporadically south of there (Noble 1991b).

Boreal coniferous species characterized dry granitic outcrops and shallow and deep glaciofluvial sands and gravels dominated by coniferous species, especially Jack pine. Representing the northern Boreal zone are the cold, wet swamp and bog peatlands dominated by boreal shrubs, sphagnum mosses, black spruce, and, occasional, larch. White birch and trembling aspen are abundant in the original park but are restricted mostly to the silty sand tills that characterize much of the northern portion (Noble 1991b).

Communities within the original park include: coniferous forest communities (black spruce, Jack pine, white spruce, white pine, red pine, and balsam fir coniferous forests); deciduous forest communities (trembling aspen and white birch deciduous forests); mixed forest (black spruce-, jack pine-, red pine-, balsam fir-, white pine-, white spruce-,trembling aspen-, and white birch- dominated mixed forests); upland meadows; rock barrens; forested swamp (forested black spruce and white cedar coniferous swamps); forested black ash swamps; thicket swamps; open and treed bogs (black spruce, open Low-shrub, and Open Graminoid treed bogs); open fens (open low-shrub and graminoid fens); and meadow, deep, and shallow marshes - meadow, emergent deep, floating-rooted, and shallow marshes (Noble 1991b).

The original Mississagi River Provincial Park exhibits distinct transitional flora, which is to be expected given its length and the fact that the boundary between the Boreal Forest Region and the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Forest Region crosses in the middle. The elements of both regions are well-represented in the area. Plants of interest include bristly sarsaparilla (Aralia hispida), Michaud’s sedge (Carex Michauxiana), round-leaved dogwood (Cornus rugosa), winterberry (Ilex verticillata), swamp fly honeysuckle (Lonicera oblongifolia), mountain-holly (Nemopanthus mucronata), Ragged-fringed orchid (Platanthera lacera), and shining willow (Salix lucida) (Noble 1991b).

The park’s linear shape is not conducive to extensive fauna habitat protection; valley corridors have a function as a travelway for animals which follow lake and river shorelines (Noble 1991b). Known nesting locations of Osprey and Bald Eagle occur in the park (Morris 2002).

Cultural resources:

The waterway has a rich history, which began centuries ago, with Aboriginal People living on the shores of the Great Lakes and paddling the Mississagi River to hunt and fish. Voyageurs and fur traders with the Northwest Company also paddled these waters. Subsequently, construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) brought trappers, bushmen, and tourists from Biscotasing; the advent of the forest industry brought lumbermen who drove pine logs down the Mississagi River to the town of Blind River. Commercial logging continued in the upper Mississagi watershed despite the Mississagi Fire of 1948, which burned over a period of five months and consumed almost 400,000 hectares of forest. While the last log drives ended in the late 1960s, the forest which resulted from the fire is now reaching maturity (Kutas 2005).

In 1912, artist Tom Thomson paddled and painted on the Mississagi River. The river’s reputation has also been associated with Grey Owl, who first came to Biscotasing in 1914 to work as a Fire Ranger along portions of the Mississagi waterway. Today, the primary use of the Mississagi River is for recreational purposes; the river is a popular destination for hunting and fishing, and a canoe route (Kutas 2005).

A cultural resources inventory of the original Mississagi River Provincial Park revealed evidence of human occupation in the area which dated from the period shortly after deglaciation (i.e., Early Archaic) to the present day. Thus, the human use of Mississagi River Provincial Park is estimated to have lasted for at least the last 9,000 years (Adams and Errington 1991).

Recreation:

The main recreational features of Mississagi River Provincial Park are the river and other waterbodies, developed land trails, accessibility by land, cultural sites, and wildlife and vegetation. Recreational activities available in the park are canoeing, motorboating, fishing, hunting, camping, and cottaging (Kutas 2005).

The Mississagi River is a provincially significant canoe route. There is a vast amount of literature on the history of the Mississagi River and area, including the river’s association with Grey Owl, who worked as a Fire Ranger along portions of the Mississagi waterway. Some areas of the park can provide solitude, as well as scenic viewscapes of cliffs and wetland areas (Kutas 2005).

Motorboating occurs in most areas of the park, except for some portions of the Mississagi River. Angling is a popular activity throughout the park; hunting is permitted in the park. Camping occurs throughout the park at existing sites on the roads and on the river, as well as along the roads leading to the park (Kutas 2005).

Inventories

| Survey Level | Earth Science | Life Science | Cultural | Recreational |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reconnaissance | Frey and Duba 2002; Noble 1991a | Morris 2002; Noble 1991b | Adams and Errington 1991 (pre OLL park) | Kutas 2005 |

Footnotes

- footnote[1] Back to paragraph Transfers include situations where a license is surrendered with a request that it be immediately reissued to another individual or organization that is assuming an existing operation. Trap cabins are considered part of a trapline and would be transferred with the trapline for the purposes of trapping. If a trapline license is revoked or surrendered, all portions of the registered line within the park will be rescinded from the legal description of the trap line (OMNR 2003).