Ontario's provincial fish strategy

The strategy was developed to guide MNRF fisheries policy development, decision making and science priorities and will provide input into other natural resource management policy and planning. It will also assist MNRF in prioritizing its efforts and coordinating its activities as it addresses new and emerging issues that impact Ontario’s fisheries resource.

Summary

This is a guiding document for managing fisheries resources in Ontario. It identifies provincial fisheries goals, objectives and tactics to achieve them. The main purposes of the strategy are to improve the conservation and management of Ontario’s fisheries resources; and to promote, facilitate and encourage fishing as an activity that contributes to the nutritional needs, and the social, cultural and economic well-being of individuals and communities in Ontario.

The Provincial Fish Strategy provides management direction to MNRF staff and will better position the ministry to respond to evolving environmental, economic, social, technological and policy challenges facing fisheries in Ontario.

1. Purpose of the provincial fish strategy

Ontario’s fisheries resources are an important part of its biodiversity

This document, Ontario’s Provincial Fish Strategy: Fish for the Future, sets out a practical and strategic framework for managing Ontario’s fisheries resources from 2015 forward. It identifies key overarching management approaches: landscape management, a risk-informed approach, and adaptive management (Section 6); specific goals, objectives and tactics (Section 7); and a proposed implementation approach (Section 8), to guide the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry’s (MNRF) stewardship of fisheries, fish communities and their supporting ecosystems.

This Strategy has two primary purposes:

- to improve the conservation and management of fisheries and the ecosystems on which fish communities depend; and

- to promote, facilitate and encourage fishing as an activity that contributes to the nutritional needs and the social, cultural and economic well-being of individuals and communities in Ontario.

This document will help to inform MNRF fisheries policy development, decision making and science priorities and will provide input into other natural resources management policy and planning. It will also assist MNRF in prioritizing its efforts and coordinating its activities as it addresses new and emerging issues that impact Ontario’s fisheries resources. In cases where decision makers must balance competing objectives for the management of aquatic systems, this document can help to provide a fisheries perspective in the discussion.

MNRF cannot manage Ontario’s fisheries resources in isolation. Collaboration and coordination – with all levels of government, First Nations and Métis communities, provincial partner agencies and stakeholders – are themes that run through this Strategy. Fish for the Future is intended to serve as a resource to guide other agencies and levels of government in their own program and policy decisions. It will also increase accountability and transparency by communicating MNRF’s priorities to First Nations and Métis communities, Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), stakeholders and the general public.

History of fisheries strategic planning in Ontario

Strategic planning for Ontario’s fisheries by the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry began more than 40 years ago, in response to the fishery declines that occurred during the rapid economic growth of the post-World War II era. The then Ministry of Natural Resources (MNR) launched its first Strategic Plan for Ontario Fisheries (SPOF) in 1976. SPOF incorporated a number of innovative elements, including public involvement, resident sport fishing licences, commercial catch quotas, and the establishment of Fisheries Assessment Units throughout the province. Under SPOF, the province’s fish hatcheries were also improved, and partnerships with other agencies were strengthened. Through District Fisheries Management Plans, developed with public input, SPOF identified long-term fisheries goals and the short-term actions necessary to achieve them. These activities slowed and reversed losses in some indigenous fish stocks in Ontario, allowing recovery to begin. SPOF was, however, narrowly focussed on individual water bodies, and did not provide the guidance necessary to manage fisheries resources at broader scales.

In 1992, MNR released the Strategic Plan for Ontario Fisheries II (SPOF II), with the goal of shifting site-specific management planning to a more comprehensive, aquatic ecosystem-based approach. While SPOF had achieved some gains, there was still widespread public concern about environmental health and a growing emphasis on sustainable management of fisheries resources. SPOF II included the notion of sustainable development, ensuring the continuation of fisheries benefits to current and future generations. It also affirmed the principle that there were limits to the productive capacity of fisheries; strengthened enforcement; and emphasized the need for science-based management strategies. SPOF II was a powerful biological and policy framework, but it was not supported by formal guidance on implementation. As a result, management continued to focus on individual water bodies, but often with little analysis to determine if management objectives were actually being met.

In 2005, the province recognized the need for a stronger emphasis on landscape level management of fisheries. A new Ecological Framework for Recreational Fisheries Management (EFFM) in Ontario replaced the 37 existing fishing “divisions” with 20 Fisheries Management Zones (FMZs) based on biological, climatic and social considerations. Regulatory tool kits were developed for key sport fish species, establishing broad-scale standards for setting fishing regulations. Key components included standardized broad-scale monitoring approaches, adaptive management, enhanced public engagement, and systematic state-of-the-resources reporting. This Ecological Framework did not set provincial fisheries management goals and objectives, however, and focussed only on the management of recreational fisheries. Shortly thereafter, MNR developed and released the Strategic Policy for Ontario’s Commercial Fisheries, 2011, which provides a framework and focus for developing operational commercial fishing policies. However, this commercial fisheries strategy was linked neither to EFFM nor to a provincial framework for fisheries management.

Ontario’s Provincial Fish Strategy: Fish for the Future incorporates and replaces SPOF II and fills the need for a new overarching strategic plan that guides the immediate and long-term management of recreational, commercial and Aboriginal fisheries resources in Ontario. It is based on the most recent science-based understanding of successful natural resources management approaches. It provides current context and identifies key social, economic and environmental trends with the potential to affect Ontario’s fisheries resources, and uses that information to guide identification of operational tactics, and ultimately the successful achievement of fisheries management goals and objectives.

2. The fisheries resource today

Ontario has a large and diverse aquatic resource with over 250,000 lakes and countless rivers and streams. Fish benefit Ontario’s ecology and ecosystems, as well as its cultures and economy. The province’s inland and Great Lakes fish communities provide a diverse range of year-round recreational, commercial and First Nations and Métis fisheries. Together, these activities and their supporting industries are estimated to contribute more than $2.5 billion annually to Ontario’s economy (see text box Ontario’s fisheries: significant contributors to the economic and social fabric of Ontario).

Aboriginal fisheries

Fish are of central importance to Aboriginal peoples in Ontario. Throughout the province, Aboriginal peoples have constitutionally-protected Aboriginal and treaty rights to fish for food, and for social and ceremonial purposes. There are also several Aboriginal commercial fisheries across Ontario, most of which stem from historical practice. Aboriginal commercial fisheries are found primarily on the Great Lakes, Lake Nipissing, Lake Nipigon, and lakes of northwestern Ontario.

The history of Aboriginal fisheries pre-dates the existence of the province. Harvest traditionally occurred year round, including during spawning times. Harvesting tools included weirs, nets, traps, spears and baited hooks. Although tools have evolved over time, fishing continues to play a significant role in the lives of Aboriginal peoples, contributing to the dietary, social, cultural and economic needs of communities in Ontario today.

The Constitution Act, 1982 recognizes and affirms Aboriginal and treaty rights of the Aboriginal peoples of Canada. MNRF has a legal duty to consult Aboriginal communities when any proposed activity or decision may adversely impact those rights. With respect to fisheries, the courts have clarified that conservation of fishery resources is the first priority, after which existing Aboriginal and treaty rights take priority before allocation and management of the resources for recreational, commercial food and bait fisheries.

Aboriginal communities also have a long history of, and strong interest in, fisheries resources management. Aboriginal Traditional Knowledge (ATK) has been gathered by Aboriginal peoples through generations of depending on the land and water resources for their survival and way of life. Aboriginal rights and interests help guide fisheries management planning and activities in Ontario. MNRF acknowledges the importance of ATK in decision making and continues to explore opportunities to increase Aboriginal involvement in fisheries management through collaborative partnerships. Far North planning is an example of how the best available information from all sources, including ATK and scientific information, is used to support decision making during the planning process.

Recreational fisheries

In 2010, more than 1.2 million resident and non-resident anglers fished in Ontario, more than in any other Canadian province or territory. Although participation in recreational fishing declined somewhat through the last decades of the 20th Century, anglers undertook an estimated 17 million days of fishing activity in 2010.

Today, recreational anglers spend more days fishing on Lake Huron than any other water body in Ontario, followed by Lakes Ontario, Erie, Simcoe and Lake of the Woods. The Ottawa River, St. Lawrence River and Grand River are also popular recreational fishing spots. Many of the province’s largest fisheries occur in reservoirs, including the Kawartha Lakes and Lac Seul. Lake Simcoe and Lake Nipissing are the most popular ice fishing destinations.

Walleye is the primary target for recreational anglers on Lake Erie. Rainbow Trout, and Chinook and Coho Salmon are naturalized species that dominate the tributary and open water recreational fisheries of the other Great Lakes, especially in Lake Ontario and Lake Huron. Coastal wetlands and nearshore warm water embayments of the Great Lakes support recreational fisheries for Smallmouth Bass, Walleye, Yellow Perch, Muskellunge and Northern Pike. Open water recreational fisheries on inland lakes preferentially target Walleye, followed by Bass and Northern Pike. Walleye, Yellow Perch, Northern Pike and Lake Trout are the most preferred species in winter ice fisheries.

Fishing is a key tourism driver in Ontario, with a large number of international anglers attracted to the Great Lakes and the pristine waters of northern Ontario. Of the approximately 1,600 resource-based tourism sites in Ontario, nearly 1,140 are not accessible by road, are located in northern Ontario, and attract 90% of fishing-focussed visitors. These remote tourism fisheries are a key economic component in many northern communities, generating more than $100 million in revenues every year.

Commercial food fisheries

Ontario’s commercial food fishery is part of our heritage and culture, and is the largest freshwater fishery in North America. Most commercial food fishing takes place on the Great Lakes, where Rainbow Smelt, Yellow Perch, Walleye and Lake Whitefish make up approximately 80% of harvest by weight. Lake Erie accounts for approximately 75% of that commercial harvest. Substantial commercial fisheries also exist on several large inland lakes, such as Lake of the Woods, Lake Nipigon and Lake Nipissing, with less significant fisheries on some of the smaller inland lakes in northwestern and eastern Ontario.

The majority of commercial fishing licences are in northwestern Ontario, where fisheries mainly target Lake Whitefish, with smaller harvests of other species. On Lake Nipissing, Walleye is the primary target species; in southeastern Ontario, a variety of warm water species are harvested. Approximately 10% of the commercial fish harvest is sold in Canada, and 90% is exported primarily to the United States, and a small proportion to Europe.

There are nearly 650 active commercial fishing licences in Ontario, of which 160 are held by First Nations communities, and First Nations and Métis individuals. In 2011, commercial licence holders caught nearly 12,000 metric tonnes (about 12 million kg) of fish. The dockside value of that harvest in 2011 was more than $33 million and, including processing, packaging, and shipping, contributed approximately 1,000 jobs and $234 million to Ontario’s economy. Commercial fishing and its industries are significant employers in many smaller Great Lakes communities, and are an important economic development initiative for many Aboriginal communities across the province.

Commercial bait fisheries

Approximately 60% of anglers in Ontario use live baitfish, supporting the largest live baitfish industry in Canada. Approximately 1,200 commercial bait licences are issued every year, representing an industry worth over $20 million annually. The bait industry harvested approximately 144 million fish in 2010. Of these, 60% or approximately 86 million were not identified to species but were simply recorded as “baitfish” (mixed bait species). Among the remaining 40%, Emerald Shiner made up the majority, with over 58 million harvested; and approximately 90,000 Cisco were also harvested. Leeches are also an important bait species, with over 26 million harvested commercially in 2010.

Bait harvesting occurs throughout the province, with the bulk of the “baitfish” and Emerald Shiner harvest coming from southern Ontario, particularly from Lakes Simcoe and Erie. Most Cisco come from across northern Ontario, and most leeches come from northwestern Ontario.

Status of Ontario’s fisheries resources

Ontario has the highest fish diversity in Canada, with 128 species native to the province and 17 naturalized species. These self-sustaining wild fish stocks provide for a diverse range of year round First Nations, Métis, commercial and recreational fisheries in urban, rural and remote areas of Ontario.

Inland waters

Populations of warm water and most cool water species are generally stable across the province. Walleye abundance is relatively high in most of northern Ontario, but in southern Ontario, lower abundance is a result of factors such as higher exploitation and competition from aquatic invasive species. Smallmouth Bass and Northern Pike are abundant across Ontario. Although Smallmouth Bass are native in much of southern Ontario, their range has expanded through introductions and migrations into central and northern Ontario lakes and rivers outside their natural range.

Smallmouth Bass fisheries are managed to provide social and economic benefits to Ontarians where appropriate, but efforts are also being made to prevent new introductions, especially in areas where negative interactions with Lake Trout and Brook Trout could occur.

Coldwater species are still widespread across their Ontario ranges but some local populations of Lake Trout and Brook Trout are now extirpated, and others have suffered declines. Excessive exploitation has undeniably played a key role in this, but aquatic invasive species and human-caused changes in habitat have also had detrimental effects. Efforts to restore self-sustaining populations of Lake Trout are underway in a number of areas and are showing varying degrees of success. Lake Trout and Brook Trout populations in sparsely populated areas of northwestern Ontario are currently the least impacted by exploitation and other stresses, but these populations could also experience the greatest impacts of climate change.

Great Lakes

With the exception of Lake Erie, where Walleye was and remains the principal predator, the deep offshore areas of the Great Lakes were once dominated by two main predators, Lake Trout and Burbot, with abundant Lake Whitefish and ciscoes providing the forage base. Those offshore fish communities have experienced drastic changes since European settlement, and many native Lake Trout, Lake Whitefish and Cisco stocks were lost. Atlantic Salmon, native to Lake Ontario, were also common until the late 19th century. The combined effects of environmental degradation of tributary streams, ecosystem changes in the lake, and overfishing led to the extinction of the Lake Ontario population. Control of the invasive Sea Lamprey, improved water quality, and focussed species and habitat rehabilitation, combined with successful salmon and trout stocking programs, have helped to rehabilitate these ecosystems. Naturalized Rainbow Trout, and hatchery-dependent populations of Chinook and Coho Salmon, now dominate the open water fish communities, especially in Lake Ontario. Lake Superior is still dominated by Lake Trout, Burbot and ciscoes, and rehabilitation efforts have helped Lake Trout re-establish as a keystone predator in Lake Huron.

Lake Erie, and the coastal wetlands and nearshore, warm water embayments of the other Great Lakes, support abundant fish communities composed of a variety of cool and warm water species. Walleye continues to be the most dominant predator in Lake Erie, foraging primarily on Yellow Perch. A number of locations around the Great Lakes have experienced significant habitat loss. In addition, historical pollution has led to increased contaminant concentrations in fish flesh and associated fish consumption advisories. Rehabilitation of habitat and improved water quality in coastal areas such as Toronto’s waterfront, Wheatley Harbour, Severn Sound and Collingwood have resulted in the recovery of nearshore fish populations such as Walleye, bass and Northern Pike, and reduced contaminant levels in fish. These areas have seen improvements because they are Great Lakes Areas of Concern and have received focussed government and community attention.

Although significant successes were achieved in restoring and protecting the Great Lakes in the 1970s, 80s and 90s, today’s pressures are overwhelming some of those gains. The cumulative impacts of human population growth and associated development, continued loss of fish and wildlife habitat, species invasions, new chemicals of concern, water level fluctuations and algae blooms have resulted in declines of native Great Lakes fish species and associated losses in commercial and recreational fishing opportunities. The waters and fisheries of Lake Superior are generally in good condition due to that lake’s larger size and relatively lower development pressure, but many indicators of lake health suggest that Lakes Huron, Ontario and Erie are in decline. For example, the number of Ontario’s aquatic species at risk is growing. Of Ontario’s 27 fish and 13 mussel species at risk, most occur in the Great Lakes and their tributaries. In response, the province has developed Ontario’s Great Lakes Strategy that sets out a vision, goals and priorities to help restore, protect and conserve the Great Lakes. The government has also proposed a new Great Lakes Protection Act to empower action by all partners on Great Lakes, to protect and restore the waters, beaches, and coast areas of the Great Lakes, and to conserve biodiversity, deal with invasive species, and address the need for climate change adaptation.

In summary, although a variety of stresses have affected the ecology and fish communities of Ontario’s lakes, rivers and streams, Ontario still offers a diverse array of fishing opportunities. Most freshwater fish species that support fisheries are self-sustaining and secure from a conservation perspective, and in some areas, especially northern Ontario, fisheries are thriving. While these gains are encouraging, continued vigilance is critical if we are to protect what we have, and restore and rehabilitate degraded populations and aquatic ecosystems.

3. Key trends and emerging issues

Ontario is a different place than when the Strategic Plan for Ontario Fisheries II (SPOF II) was released in 1992. The province’s population, economy, and environment have all changed dramatically in the intervening years, altering the location and nature of pressures on fisheries resources.

Recognizing these forces, MNRF conducted an environmental scan as a means of understanding the key trends and emerging issues affecting Ontario’s fisheries resources.

Table 1 provides a summary of the results of that scan

| Type of driver | Threats/pressures | Opportunities |

|---|---|---|

| Economic |

|

|

| Social |

|

|

| Technological |

|

|

| Policy and Legislation |

|

|

| Environmental |

|

|

Several points emerge from this environmental scan. First, certain drivers, especially population growth, demographic trends, and the location and nature of fishing interests, are difficult to predict with certainty but will continue to pose challenges for fisheries management. Invasive species and climate change are the most significant and growing concern for fisheries. Climate change will bring a suite of complex effects including changes in food web structure and the timing and success of fish reproduction; more frequent extreme weather events (and thus increased likelihood of habitat disruption); more invasive species; and greater susceptibility to native and non-native pathogens. These drivers operate at broad spatial and temporal scales, well beyond the level of a local stream or lake, and must be understood and managed accordingly. Uncertainty is high, and the knowledge base is still evolving. There is therefore a need for adaptive management, periodically revisiting and revising management objectives and strategies as information about stressors and environmental response improves.

These and other major changes in Ontario’s environmental, social, political, and economic conditions over the last two decades signal the need for this new strategic plan for the province’s fisheries. The following sections describe the strategic planning context; fisheries management roles, responsibilities and management approaches; and the goals, objectives and tactics of this Provincial Fish Strategy.

4. The current strategic planning context

Ontario’s Provincial Fish Strategy: Fish for the Future builds on the legacy of over forty years of fisheries strategic planning, providing a practical framework to guide MNRF’s management of the province’s fisheries resources. It is guided by other MNRF strategic direction, including Our Sustainable Future: A Renewed Call to Action (2011); Biodiversity: It’s In Our Nature (2012); MNRF’s Statement of Environmental Values (SEV); the Joint Strategic Plan for Management of Great Lakes Fisheries, and the guiding principles that derive from these documents (Figure 1).

This Provincial Fish Strategy is consistent with the description of MNRF’s core mandate – to conserve biodiversity and manage natural resources in a sustainable manner – and with the organizational goals articulated in MNRF’s Strategic Direction:

- Ontario’s ecosystems withstand pressures and threats;

- Ontario’s natural resources contribute to sustainable economies and ecosystems;

- A trusted and accessible source of knowledge about Ontario’s natural resources;

- People, property and natural resources protected from hazards;

- Ontarians are actively involved in achieving biodiversity conservation and sustainable use; and

- Trusted by Ontarians to deliver results with an enthusiastic and engaged workforce.

The Provincial Fish Strategy embraces a landscape approach to fisheries management, consistent with MNRF policy direction outlined in Taking a Broader Landscape Approach – A Policy Framework for Modernizing Ontario’s Approach to Natural Resource Management (2013), and provides direction on how the approach will be applied in the context of fisheries management.

Figure 1. Ontario’s Provincial Fish Strategy provides the link between high level strategic direction and the various tools and activities used to manage Ontario’s fisheries.

- Constitution of Canada

- Federal and provincial natural resource legislation

“The Legal Authority”- MNRF strategic direction

“Long-term Strategic Directions and Priorities for MNRF” - Ontario’s provincial fish strategy goals, objectives and tactics

“Linking Strategic Direction and Fisheries Management”- Policy

- Guiding decisions related to the protection and management of fisheries resources

- Management

- Implementing fisheries resources management planning and activities

- Enforcement

- Compliance planning and activities to support fisheries management priorities

- Science & information

- Delivery of data, information and knowledge to support fisheries management priorities

- Policy

- MNRF strategic direction

- Federal and provincial natural resource legislation

5. Roles & responsibilities for fisheries management

Legislative and policy framework

Under Canada’s Constitution Act, responsibility for fisheries management is divided between the federal government, which has authority over the seacoast and inland fisheries, and the provinces, which have authority over natural resources, management and sale of public lands, and property and civil rights. At the federal level, Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) has primary responsibility for fisheries; in Ontario, the primary agency is MNRF. Other agencies and levels of government also have mandates that include aspects of fisheries management. Examples include Transport Canada (federal), the Ontario Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change (MOECC), Ontario’s Conservation Authorities, national and provincial parks, and municipalities.

The protection of fish and fish habitat is a responsibility of the federal government. DFO uses the federal Fisheries Act to protect fish and fish habitat, ensure passage of fish, and prevent pollution that can have detrimental impacts on fish populations. The 2012 amendments to the Act have shifted its focus to providing for the sustainability and ongoing productivity of commercial, recreational, and Aboriginal fisheries (including habitat and the fish that support them), as opposed to protecting the habitat of all fish.

DFO has created a Fisheries Protection Policy Statement that outlines how DFO and its regulatory partners (including MNRF) will apply the Fisheries Protection Provisions of the Fisheries Act, guide the development of regulations, standards and directives, and provide guidance to proponents of projects on the application of the Fisheries Protection Provisions of the Fisheries Act.

MNRF is the agency responsible for administering and enforcing the Ontario Fishery Regulations under the Fisheries Act, including allocation and licensing of fisheries resources, fisheries management (e.g., control of angling activities and stocking), fisheries management planning, fish and fish habitat information management, and fish habitat rehabilitation. Ontario works with DFO to help achieve the requirements of the Fisheries Act through agreements and protocols. The Fish Habitat Referral Protocol for Ontario is currently being updated to reflect the recent changes to the Fisheries Act.

The ministry also has fisheries responsibilities under the federal Aboriginal Communal Fishing Licences Regulations, and the Ontario Fish and Wildlife Conservation Act. Under Ontario’s Environmental Bill of Rights, MNRF is required to consider the ministry’s Statement of Environmental Values in evaluating each proposal for instruments, policies, statutes, or regulations that may significantly affect the environment.

Section 35 of the Fisheries Protection Provisions of the Fisheries Act prohibits serious harm to fish and applies to fish and fish habitat that are part of or support commercial, recreational or Aboriginal fisheries. Serious harm to fish is defined in the Act as “the death of fish or any permanent alteration to, or destruction of, fish habitat.” When issuing a Section 35 authorization, DFO must consider the following four factors (outlined in Section 6 of the Act):

- the contribution of the relevant fish to the ongoing productivity of commercial, recreational or Aboriginal fisheries;

- fisheries management objectives;

- whether there are measures and standards to avoid, mitigate or offset serious harm to fish that are part of a commercial, recreational or Aboriginal fishery, or that support such a fishery; and

- the public interest.

Other federal and provincial laws and national and international agreements also touch on the management of fish, fisheries and their supporting ecosystems in Ontario. Examples include the Ontario Lakes and Rivers Improvement Act, the Crown Forest Sustainability Act, the Public Lands Act, the Provincial Parks and Conservation Reserves Act, the Environmental Assessment Act and the Planning Act. For example, under the Crown Forest Sustainability Act, forestry operations must follow Forest Management Plans and adhere to site-specific environmental protection requirements in and around water to protect fish habitat. Another example is land use planning for Crown lands, a process that is led by MNRF under the authority of the Public Lands Act, and guided by the Crown Land Use Policy Atlas. This planning includes establishment of broad direction for resource-related activities and road access, both of which may impact fisheries and aquatic ecosystems. A last example is the Provincial Policy Statement (PPS), issued under the Planning Act, which integrates all provincial ministries’ land use interests related to municipal planning and development. While the Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing (MMAH) has overall responsibility for the PPS, MNRF has the lead for policies and the provision of technical advice regarding the protection of fish habitat, through the Natural Heritage Reference Manual.

Fisheries management tools

MNRF’s mandate is delivered through statutes, regulations, policy, planning, program development and program delivery. A variety of fisheries management tools are available, and the right tool for one job may not be ideal for another:

- Fisheries management planning: Fisheries management planning provides guidance for managing fisheries at multiple spatial and temporal scales. Planning is focussed on ensuring the sustainability of fisheries and informs the allocation of fisheries resources within the planning area to provide a range of social, cultural and economic benefits.

- Regulation of commercial and recreational fisheries: Under the authority of the Fisheries Act, MNRF issues licences via the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Act for various fisheries activities in Ontario: commercial food and bait fisheries, recreational fishing, stocking, aquaculture, and the collection of fish for scientific purposes. Licence conditions can set limits on those activities or outline measures to minimize any unintended impacts of those activities. One of the best-known tools for managing self-sustaining fisheries is setting fishing regulations to control how many, where, and how fish are harvested. Regulations can include seasons, creel limits or quotas, and size restrictions for recreational and commercial fisheries.

- Fish stocking is an important fisheries management tool. Fish that are raised at MNRF’s nine fish culture stations and community hatcheries are stocked to create Put-Grow-Take (PGT) fisheries that provide additional angling opportunities. In certain situations, stocked fish may help to restore degraded fish populations. MNRF is currently developing strategies for culturing and stocking aquatic species at risk, in support of recovery efforts for those species.

- Fish habitat protection: Sustainable fisheries require a diversity of fish communities supported by healthy aquatic ecosystems and associated fish habitat. DFO has the primary responsibility for the protection of fish habitat under the Fisheries Act (Parks Canada manages fish habitat in national parks, national marine conservation areas, and the national historic canals). As a partner in these efforts, MNRF develops guidelines and best management practices and works with MMAH to provide advice to municipalities on how to protect fish and fish habitat through municipal land use planning. MNRF also incorporates fish and fish habitat protection into its own land-use and resource management plans.

- Fish habitat rehabilitation: In Ontario, MNRF is the provincial agency responsible for fish habitat rehabilitation. MNRF may also actively participate in habitat rehabilitation activities, either alone or through partnerships.

- Research and monitoring are key components of MNRF’s commitment to science-based decision making. These activities provide critical information on the status of fisheries, fish communities and supporting aquatic ecosystems, and thus support the evaluation of fisheries management actions over time.

- A risk-based framework for compliance and enforcement planning supports fisheries management by focusing efforts on areas of highest risk to fisheries resources. This approach helps to ensure compliance with fisheries legislation in areas where threats are greatest or the resources most need protection.

While MNRF has clear responsibilities related to fisheries management in Ontario, it is equally clear that the ministry must depend on other agencies such as DFO, MOECC, and Conservation Authorities to successfully deliver its mandate, especially in the role of protecting the aquatic ecosystems on which fish populations depend. Other forces and decisions outside MNRF, for example, those related to Aboriginal and Treaty rights, environmental assessment processes, or judicial (court) decisions, will also affect the ways that fisheries are managed in Ontario.

For border waters with shared jurisdiction, MNRF relies on good working relationships with neighbouring provincial and state agencies, and co-operative efforts through bi-national groups such as the Great Lakes Fishery Commission (see text box). In addition to agency partnerships, MNRF also depends on the people of Ontario to act as responsible stewards of the fisheries resources. Planning for, and protecting Ontario’s fisheries resources is a shared stewardship responsibility.

6. Key management approaches

MNRF manages natural resources and their use across Ontario’s diverse ecosystems, addressing regional and local differences in social, economic and ecological objectives. This requires the integration of management objectives and approaches for many species and their habitats, in the context of varied human activities and multiple stressors.

An ecosystem-based approach to management has long been advocated as the best way to address the complex resource management challenges associated with diverse and complex landscapes, whether terrestrial or aquatic. Moving toward an ecosystem-based approach to managing Ontario’s fisheries resources will mean shifting management to broader spatial scales, over longer time periods. It also requires acknowledgement of uncertainty. One of the greatest challenges of natural resources management is the absence of complete knowledge of natural systems. Decisions must therefore be based on the best available science and knowledge, and reviewed periodically as the knowledge base improves. The Precautionary Principle guides this process (see text box).

It is challenging to balance the economic and social benefits of development with fisheries and ecosystem goals. In some cases, decisions made outside of MNRF’s mandate have consequences for provincial fisheries. A structured and inclusive decision-making process can help to clarify the local context and ensure that risks and benefits to the resources and its users are well understood. Such an approach can also help to integrate fisheries planning with other relevant planning processes where possible, and inform the development of appropriate mitigation measures where impacts cannot be avoided.

MNRF is also committed to continuous improvement of natural resources management outcomes and understanding of aquatic ecosystems. To this end, the ministry endorses the use of a landscape-scale, risk-informed and adaptive approach to management wherever possible. These approaches are reflected in the Strategy’s Guiding Principles (see Section 6).

Their application to fisheries management is described in more detail in the following paragraphs.

Landscape approach: managing at appropriate scales

Adopting a landscape-scale approach to fisheries management promotes better understanding of how natural systems work and how they are affected by human activities. It means taking an ecosystem approach to management and acknowledging that there is a limit to the natural capacity of aquatic ecosystems. It also requires that resource management goals and objectives be balanced against other challenges, issues, and needs across the broader landscape.

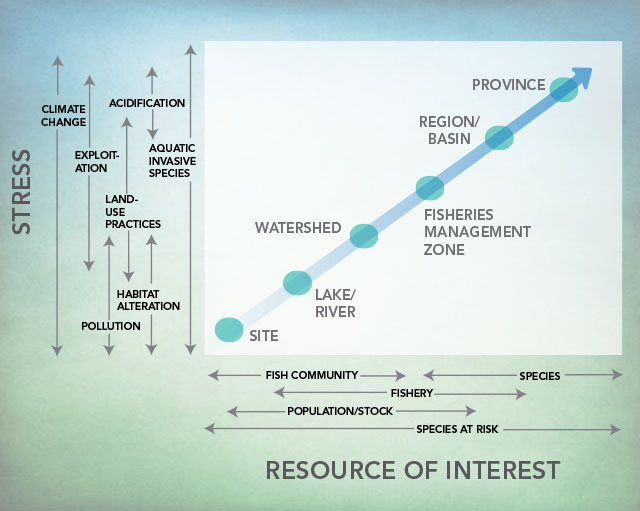

Generally, a landscape approach means managing over broader spatial scales and over longer time periods, but that is not always the case. Landscapes for managing fisheries in Ontario are defined at multiple spatial and temporal scales (see Figure 2). The most appropriate scale for planning, management and monitoring depends on:

- Ecological factors, such as the provincial climate zones, natural hydrological boundaries such as watersheds, and fish species distribution patterns

- The type, status and extent of the resources of interest, such as the type of fishery, species, and fish community

- The type, extent and intensity of the stress that is being managed, such as habitat alteration, fishing pressure, invasive species, and climate change

- Social and economic factors such as population size, demand for fishing, jurisdictional boundaries and road access

Applying the landscape approach in fisheries management

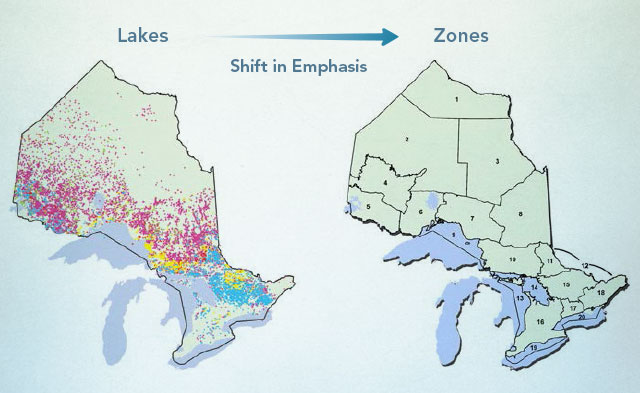

Many stressors on fisheries, such as fishing pressure, invasive species and climate change, operate at broad scales, well beyond the level of a local stream or lake, and must be understood and managed at the landscape level. In 2008, MNRF moved toward a broader landscape scale approach to managing recreational fisheries by establishing 20 Fisheries Management Zones (FMZs) as the primary units for planning, management and monitoring most fisheries in Ontario. The boundaries of the FMZs were determined using a combination of ecological factors, such as watershed boundaries and climate, and social factors including fishing pressure and road access (see text box). Management Plans for each FMZ document the desired future state of the fisheries resources, and interpret provincial goals and objectives in the establishment of zone-level and local fisheries objectives and actions. For most recreational fisheries, management actions are applied across the zone, whereas quotas related to inland commercial food fisheries apply to individual water bodies within a zone.

Landscape-scale management of lake trout: different scales for different stresses

Lake Trout is a sensitive coldwater species that also needs high dissolved oxygen in the deep waters of a lake, or hypolimnion. It is vulnerable to many stresses, including high rates of exploitation, acid precipitation, species invasions, eutrophication, and habitat loss. Protecting or rehabilitating Lake Trout populations in the face of these varied stresses can mean applying a combination of different management tools at different scales.

MNRF has developed a science-based provincial policy to evaluate lakeshore development capacity on all inland Lake Trout lakes on the Precambrian Shield. The policy uses a threshold based on a hypolimnetic dissolved oxygen criterion (7 mg/L) to determine if a Lake Trout lake is at capacity for shoreline development. If measured oxygen is below the threshold, or modelling suggests that development could cause that to occur, the lake is considered “at capacity” for development. At the local scale, MNRF encourages municipalities to identify “at capacity” Lake Trout lakes in their Official Plans, consistent with direction in the Provincial Policy Statement. MNRF maintains a formal list of designated Lake Trout lakes that is reviewed and updated periodically.

MNRF has also used a landscape approach and a variety of management tools such as fishing regulations and Lake Trout lake prescriptions for Forest Management Plans at a regional scale. The prescriptions are aimed at preventing unplanned access to natural Lake Trout lakes, while implementing sound forest management practices. The approach allows for additional restrictions on the construction, use, or decommissioning of roads around certain aquatic features such as lakes containing sensitive self-sustaining populations of Lake Trout or Brook Trout. Those decisions are made at the discretion of planning teams in the context of zone-wide fisheries management objectives and strategies developed with the advice of Fisheries Management Zone advisory councils. The hope is that this broader landscape-scale approach will protect sensitive fish populations from over-exploitation and other stressors such as aquatic invasive species.

Each of the Great Lakes is also a FMZ, but in these bi-national systems fisheries are managed at an international scale. The Great Lakes Fishery Commission promotes and facilitates bi-national management of commercial and recreational fisheries on the Great Lakes. Specific fish community objectives for each lake have been jointly agreed upon by the Canadian and U.S. management agencies, including MNRF. In terms of the commercial fishery, each Great Lake is partitioned into quota management zones. Within the Canadian waters of each lake, MNRF issues licences, sets annual individual species catch quotas, and monitors harvests by commercial fishermen within quota management zones. Quotas are adjusted periodically as part of an adaptive management strategy.

Fisheries Management Zones also exist in the Far North, but fisheries planning mechanisms and processes are not yet well defined. Management of fisheries presents a challenge because of the vast and sparsely populated geographic area. In this region, it is especially important to involve First Nations and Métis communities and stakeholders in the planning and management of fisheries. In some areas, integration of fisheries management planning with community planning is already underway.

Although the primary focus of fisheries management is at a Fisheries Management Zone scale, fisheries planning and management activities also occur at other scales. Site-specific management occurs most often when mitigating impacts of development or when restoring fish populations and aquatic ecosystems. Sub-zone fisheries management planning can be used at various scales, for example for Provincially Significant Inland Fisheries (PSIFs); for selected urban watersheds with highly valued fisheries or significant resource pressures; and for large parks and protected areas.

The decision to undertake sub-zone planning depends on the resources of interest, the assessed risk, and the specific management objectives. PSIFs are selected through a risk-informed process, and are managed and monitored individually. Conservation Authorities are actively engaged in the planning and management of individual watersheds,to improve sustainability and prevent loss of fish habitat and productivity related to land and water use. Watershed-Based Fisheries Management Plans (WBFiMPs) are sometimes developed as a companion to a Watershed Management Plan, and provide a framework to guide the protection, rehabilitation and enhancement of fisheries resources in a watershed.

Managing recreational fisheries at a landscape scale

Historically, recreational fisheries management occurred across 37 Fishing Divisions, but by the early 1980s, local managers recognized that the resource was suffering and new approaches were needed. To address the issue, they developed individual lake regulations, and focussed the management and monitoring of fisheries resources on individual lakes. The number of regulations increased exponentially, and it was soon apparent that the approach was both costly and ineffective. In particular, it failed to recognize the mobility of anglers, who move from one water body to another to avoid more restrictive regulations in a given location.

In January 2008, MNRF took a new approach to fisheries planning and management, establishing 20 Fisheries Management Zones (FMZs) to replace the former 37 Fishing Divisions. The new FMZ boundaries are based on ecological factors and angler use patterns, and reflect the province’s climate zones, watershed boundaries, fishing pressure, and road networks. These zones are now the unit of management for most fisheries in Ontario, and form the basis for fishing regulations such as catch limits and seasons. Fish communities are monitored and assessed at the zone level. Where higher risk exists, in systems with significant social, economic, or ecological importance (e.g., Lake Simcoe and Lake Nipissing), management still occurs on an individual lake basis.

Risk-informed approach: recognizing risk and uncertainty

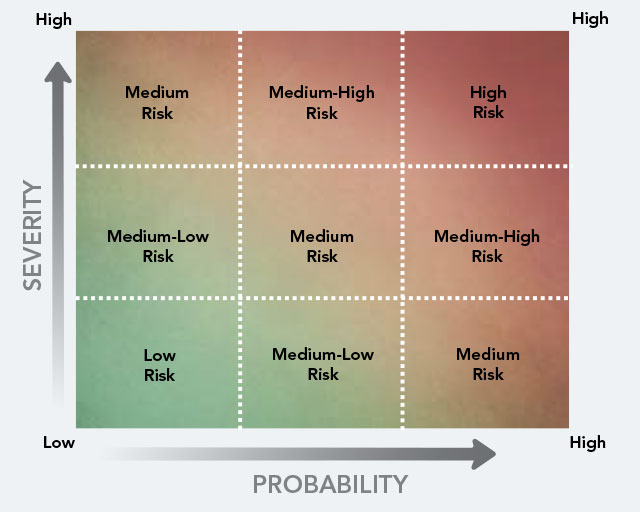

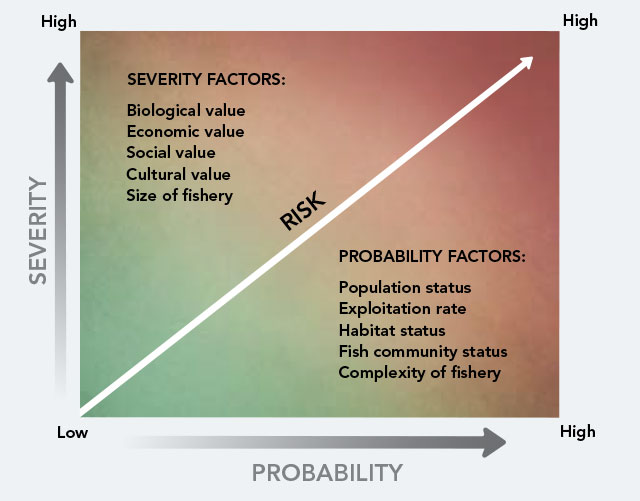

Understanding and managing risk is essential to good fisheries management. In determining acceptable levels of risk, the social, economic, and ecological benefits provided by fish and aquatic ecosystems must be considered. Natural systems are inherently variable, and knowledge of them is never complete. A risk-informed fisheries management approach acknowledges this uncertainty, taking into account the probability and severity of unacceptable outcomes (impacts) when making resource management decisions (Figure 3). Both probability and impact are estimated quantitatively based on the best available scientific, expert and traditional knowledge, including social and economic values. Risk assessment is one tool, used in combination with others, to help MNRF set priorities to address threats and identify the most vulnerable species, communities and ecosystems. Vulnerability assessment supports risk assessment by evaluating the ecological or biological mechanisms that prevent organisms, habitats and/or processes from coping with stress (for example, from a warming climate) beyond a certain tolerance range. It can help fisheries managers identify ways to reduce risks and impacts to fisheries resources and the people that depend on them.

Risk assessment must consider the cumulative effects of past, present and future developments. This is particularly important for fisheries with past or ongoing challenges, those at higher risk, and those of significant social, economic or ecological importance. Cumulative impacts may be additive (for example, the impact of repeated activities in the same area over a period of time) or synergistic (for example, the combined impact of a warmer climate, increasing human development in the watershed, and deteriorating water quality). Cumulative impacts can be challenging to assess, so the Precautionary Principle must be used in evaluating actions or policies with the potential to contribute to cumulative impacts on fisheries.

Figure 3.

| Severity | Low probability | Medium probability | High probability |

|---|---|---|---|

| High severity | Medium risk | Medium-high risk | High risk |

| Medium severity | Medium-low risk | Medium risk | Medium-high risk |

| Low severity | Low risk | Medium-low risk | Medium risk |

- A simplified risk matrix. Risk is the product of the severity of an unacceptable outcome and the probability of occurrence of that outcome. As either severity or probability increase, risk becomes greater.

- An example of factors used to determine risk to a fishery. If population status is low or habitat is degraded, for example, the probability of an unacceptable outcome increases. If biological, economic, social, or cultural values are high, the severity of an unacceptable outcome increases.

Severity factors

- Biological value

- Economic value

- Social value

- Cultural value

- Size of fishery

Probability factors

- Population status

- Exploitation rate

- Habitat status

- Fish community status

- Complexity of fishery

Ideally, fisheries management decisions should take place in a structured and inclusive risk-informed process, guided by the MNRF Risk Management How-to Guide, to clearly define the factors to be considered and the likelihood and impact of specific outcomes. This process must consider broad landscape (or watershed) patterns and processes, while also being sensitive to the local context. Care must be taken to ensure that healthy resources continue to be protected, and that attention is not directed only to the highest-risk species or areas. Monitoring is particularly important in tracking dynamic ecosystem conditions over wider areas and longer timeframes. Management strategies must be reviewed and adjusted over time, because of the uncertainty inherent in dealing with natural systems.

Applying the risk-informed approach in fisheries management

MNRF is currently using a structured risk-informed approach to designate Provincially Significant Inland Fisheries and thus determine the appropriate scale and intensity of fisheries monitoring and management. Key factors considered in the risk assessment include the social and economic value of the fishery, harvest stress, and the cumulative effects of other stressors. While most fisheries planning and management will now occur at the scale of FMZs, significant fisheries such as Lake of the Woods, Lake Nipissing, and Lake Simcoe will continue to be managed individually, through lake-specific objectives and management actions. In some cases, lake- specific monitoring programs may also be required to measure progress toward management objectives, both locally and in the context of the Fisheries Management Zone in which they occur.

Once risk has been assessed, management actions can help to reduce the probability or severity of impacts, and therefore reduce risk. Where impacts cannot be avoided, mitigation may be necessary, and risk assessment can help to inform decision making. A risk-informed mitigation framework incorporates a hierarchy of action:

- Avoid: Where possible, impacts should be prevented or avoided, for example by adjusting reservoir water level or flow to reflect the needs of migrating

- Minimize: When impacts cannot be avoided, they should be minimized in space and over time, for example by adjusting the time period over which a policy might apply.

- Mitigate: In situations where impacts cannot be avoided and steps to minimize losses are not sufficient to meet objectives, mitigation in the form of restoration, rehabilitation, or repair is the next preferred

- Compensate: If residual impacts remain following minimization and mitigation, compensation can be used to replace, provide substitutes, or offset damage and biodiversity For example, under the Fisheries Act, compensation occurs in the form of offsetting measures taken to counterbalance the residual serious harm to fish. Offsetting measures must be focused on improving fisheries productivity, and preference is given to measures that are nearby or within the same watershed.

Adaptive management approach: learning through doing

Adaptive management is a structured and systematic process of “learning through doing” – continuously improving management approaches and policies over time. In an adaptive management approach, objectives are clearly articulated, preferred management strategies are implemented, and the system is monitored and evaluated over time. Periodically, results are reviewed and compared against expected outcomes and management strategies are adjusted as necessary to reflect improved understanding of the managed system or altered levels of risk to the resources. This allows managers to recognize and adapt to the uncertainty typical of human and ecological systems, and identify and fill gaps using science, information and local and Aboriginal Traditional Knowledge. Strong monitoring and compliance programs support this approach, ensuring that system condition is tracked regularly and that unintended impacts do not cause serious decline or damage to the fishery. Adaptive management is most successful when meaningful engagement of First Nations and Métis communities and stakeholders occurs at key points throughout the cycle, to provide advice on setting management objectives, reviewing progress against objectives, and adjusting management strategies to improve outcomes. MNRF is committed to meeting its constitutional and other legal obligations in respect of Aboriginal peoples, including the duty to consult.

Applying the adaptive management framework in fisheries management

MNRF has moved toward an adaptive management approach for managing recreational fisheries in Ontario (Figure 4). Fisheries management plans are developed in consultation with advisory councils and committees. Monitoring Regulatory & Policy Framework Direction for guiding fisheries management and decisions over the long term at a broad scale, and more intensively where required, is critical in assessing the effectiveness of management actions in meeting objectives. It provides a basis for interpreting results and comparing them to predicted outcomes, and thus guides future actions. The results of monitoring are documented and reported to the public as part of a transparent management approach.

Figure 4: Fisheries management framework within an adaptive management cycle.

Regulatory & policy framework

Direction for guiding fisheries management and decisions

- First Nations & Métis Involvement

Stakeholder & Public Input- 1. Fisheries Management Planning

Set Fisheries Goals & Objectives, Identify Strategies & Actions- 2. Fisheries Management Actions

Quotas, Regulations, Stocking, Rehabilitation, Enforcement, Protection, Mitigation, Stewardship- 3. Monitoring, Assessment, Research

Evaluate Goals & Objectives, Understand Results- 4. Reporting

Technical Reporting

Public State of Resource Reporting- Return to step 1

- 4. Reporting

- 3. Monitoring, Assessment, Research

- 2. Fisheries Management Actions

- 1. Fisheries Management Planning

For a number of years, MNRF has successfully used adaptive management for commercial fisheries on the Great Lakes. Information provided by commercial fishers through mandatory reporting, combined with independent monitoring data where risks are higher, provides basic information that is analyzed on an annual basis. Fishing quotas are adjusted annually, based on the results of data analyses and input from interested parties, with whom the data and results are shared: commercial fishers, FMZ advisory councils, First Nations and Métis fishers. This adaptive approach allows managers to assess the impacts of changing harvest levels on fish stocks each year, consider socio-economic factors that sometimes come into play, and adapt management approaches accordingly.

Indicators and benchmarks can be used to assess the state of fish populations, set management objectives, and guide management decisions related to single- or multi-use fisheries on individual lakes or at broader scales. Indicators are the variables that are measured to track progress toward fisheries objectives, for example the measured fishing mortality rate of a fish population, measures of biomass, or the number of age classes. Benchmarks are limits or reference values of the indicator. For example, as a general principle, Maximum Sustainable Yield (MSY) is achieved when fishing mortality (F) is less than natural mortality (M). On an individual water body, the state of a fish population can be assessed by comparing indicator measurements to benchmarks. At a landscape scale, fisheries can be assessed by comparing the proportion of fish populations that meet or exceed benchmarks.

Indicators and benchmarks are powerful tools in adaptive management of fisheries. As exploitation approaches MSY, yields and associated social and economic benefits increase, but the biological risk to the resource also increases (see text box). Input by stakeholders and First Nations and Métis peoples can help to determine the optimum balance between benefits and risks. For example, where the fisheries management objective is to maximize yield, and higher levels of risk can be tolerated, fishing mortality benchmarks can be set close to those at MSY. On the other hand, where the objective is to have a high quality fishery with high catch rates over the long term, the tolerance for risk is lower, and benchmarks can be set well below MSY to maintain high population abundance.

The application of benchmarks to fisheries is still evolving as knowledge of the managed systems improves. For example, defining an appropriate fishing mortality benchmark requires data on the natural mortality rate and other life history characteristics of a species, in addition to its geographic location and the selective harvest management strategies in use. Decision-support tools are also evolving, for instance to help predict the effect of management actions on fishing mortality and define natural mortality rates for harvested species. Development of such tools is a key priority under this Strategy.

7. Ontario’s provincial fish strategy

As noted in the introduction to this document, this Provincial Fish Strategy identifies goals, objectives and tactics to guide MNRF’s management, science and cooperative activities for managing Ontario’s fisheries resources. MNRF’s vision describes the optimal state of Ontario’s fisheries resources, while the mission defines MNRF’s role in achieving the Strategy’s goals and objectives (see text box).

The strategy is intended to be a flexible, evolving document that allows MNRF and its partners to address new management challenges and priorities as they emerge.

It has two main purposes:

- To improve the conservation and management of fisheries and the ecosystems on which fish communities depend; and

- To promote, facilitate and encourage fishing as an activity that contributes to the nutritional needs, and the social, cultural and economic well-being of individuals and communities in Ontario.

This strategy will help inform MNRF fisheries policy development, decision making and science priorities, and will provide input into other natural resources management policy and planning processes. It will assist MNRF in prioritizing its efforts and coordinating its activities as it addresses new and emerging issues that impact Ontario’s fisheries resources.

The scope of Ontario’s Provincial Fish Strategy extends across management and conservation of all existing and potential freshwater fisheries of the Great Lakes, and the inland lakes, rivers and streams of Ontario. These fisheries vary in magnitude and complexity and include recreational, commercial, and First Nations and Métis fisheries. The Strategy is intended to be inclusive of all fisheries, whether based on wild or stocked fish, in urban areas or remote areas, large water bodies or small ponds and streams. It is guided by a number of ecological principles and principles of conduct, as described below.

In addition to providing direction for MNRF, the Strategy also lays out objectives and tactics that allow MNRF to support and guide the work that other government agencies, First Nations and Métis communities, and non-government partners undertake to conserve and manage fish populations and promote fishing.

This strategy is framed around three levels of guidance:

- Long-term, aspirational Goals that reflect ideal future conditions.

- Goal 1: Healthy ecosystems that support self-sustaining native fish communities.

- Goal 2: Sustainable fisheries that provide benefits for Ontarians.

- Goal 3: An effective and efficient program for managing fisheries resources.

- Goal 4: Fisheries policy development and management decisions that are informed by sound science and information.

- Goal 5: Informed and engaged stakeholders, partners, First Nations and Métis communities and general public.

- Shorter-term, more specific Objectives that represent categories of activity; and

- Detailed and specific Tactics that MNR, either alone or in partnership with others, can undertake to contribute to achievement of Goals and Objectives

As will be apparent from this list, Goals 1 and 2 address conservation of biodiversity and sustainable fisheries, while Goals 3, 4, and 5 provide the administrative and policy framework within which fisheries and fish habitat are managed. Progress toward desired outcomes will be measured regularly and reported to the public through State of Resource Reporting.

The following sections describe each goal in more detail, and discuss associated objectives and tactics for each.

Principles

The following principles of ecology and conduct are values that will be used to guide fisheries management planning and decision making, and are considered key to achieving the desired future state of the fisheries resources in Ontario. They are derived from broader MNRF Strategic Direction.

Ecological principles

Natural capacity: There is a limit to the natural capacity of aquatic ecosystems and hence the benefits that can be derived from them. Self-sustaining populations can provide long-term benefits when harvested at levels below Maximum Sustainable Yield.

Naturally reproducing fish communities: Self-sustaining fish communities based on native fish populations will be the priority for management. Non-indigenous fish species that have become naturalized are managed as part of the fish community, consistent with established fisheries management objectives.

Ecosystem approach: Fisheries will be managed within the context of an ecosystem approach where all ecosystem components including humans and their interactions will be considered at appropriate scales. The application of the ecosystem approach includes the consideration of cumulative effects.

Protect: Maintaining the composition, structure and function of ecosystems, including fish habitat, is the first priority for management, as it is a lower-risk and more cost effective approach than recovering or rehabilitating ecosystems that have become degraded.

Restore, recover, rehabilitate: Where native fish species have declined or aquatic ecosystems have been degraded, stewardship activities such as restoration, recovery and rehabilitation will be undertaken.

Fish and aquatic ecosystems are valued: Fisheries, fish communities, and their supporting ecosystems provide important ecological, social, cultural, and economic services that will be considered when making resource management decisions.

Principles of conduct

Aboriginal and treaty rights: Aboriginal rights and interests in fisheries resources will be recognized and will help guide MNRF’s plans and activities. MNRF is committed to meeting the province’s constitutional and other obligations in respect of Aboriginal peoples, including the duty to consult.

Informed transparent decision making: Resource management decisions will be made in the context of existing management objectives and policies, using the best available science and knowledge in an open, accountable way through a structured decision making process. The sharing of scientific, technical, cultural, and traditional knowledge will be fostered to support the management of fish, fisheries and their supporting ecosystems.

Collaboration: While MNRF has a clear mandate for the management of fisheries in Ontario, successful delivery of this mandate requires collaboration with other responsible management agencies, First Nations and Métis communities, and others who have a shared interest in the stewardship of natural resources.

Goal 1: healthy ecosystems that support self-sustaining native fish communities

Ontario’s vast array of recreational, commercial and First Nations and Métis fisheries are dependent on healthy aquatic ecosystems, including high quality fish habitat. The focus of Goal 1 is to protect and rehabilitate or restore native fish communities and their supporting ecosystems and habitats, and to avoid introductions of new species. Some of Ontario’s aquatic ecosystems, such as the Great Lakes, have been irreversibly altered. In many cases, species have been introduced and are now naturalized, providing significant economic, social, and in many cases ecological benefits.

Like native species, naturalized species and their supporting ecosystems and habitats should be afforded protection and rehabilitated or restored consistent with established fisheries management objectives.

The health of ecosystems is usually assessed against three main attributes, all of which can be examined at various scales, from a site to a provincial scale:

- Composition, including the diversity and abundance of the species present;

- Structure, the physical arrangement of the ecosystem, including the types and pattern of habitats, and how they are connected; and

- Functions, the processes that drive change in the system, including photosynthesis, predation, decay and nutrient cycling, and soil formation, and natural disturbances such as wind and fire.

Goal 1 objectives:

1.1 Protect and maintain aquatic ecosystem diversity, connectivity, structure, and function, including fish habitat.

1.2 Protect the composition of native fish communities.

1.3 Restore, recover or rehabilitate degraded fish populations and their supporting ecosystems, including fish habitat.

1.4 Prevent unauthorized introductions and slow the spread of invasive fish and other aquatic species, including pathogens.

1.5 Anticipate and mitigate or adapt to large scale environmental changes and minimize cumulative environmental effects.

Depending on their location, Ontario’s aquatic ecosystems have varying thermal regimes and can support warm, cool or cold water fisheries that vary in their natural productivity and diversity across the landscape. Within each ecosystem, there are a variety of habitats on which fish populations depend. Habitats play a critical role in the survival of a species, by providing the specialized requirement for shelter, food and reproduction that a species needs to fulfill its complex life cycle.

Ecosystems are inherently dynamic, changing in response to shifts in the mixture and abundance of species and their physical surroundings. Ecosystems with more native biological diversity are more resilient – better able to withstand disturbance and return to a natural range of variation If disturbance exceeds an ecosystem’s ability to respond, the ecosystem can shift into a new and potentially unstable condition. Protection and conservation of aquatic ecosystems, including fish habitat, is therefore critical for supporting self- sustaining fish populations and protecting Ontario’s fisheries resources.

The five Objectives under Goal 1 are aimed at protecting and managing native fish populations and the diversity, connectivity, structure, and function of Ontario’s aquatic ecosystems, and restoring or rehabilitating them where they are degraded. This includes avoiding or mitigating stressors, such as habitat alteration, invasive species, and pollution, which can have direct impacts (e.g., sedimentation of spawning beds, barriers to fish migration) or indirect impacts (e.g., removal of shoreline vegetation, leading to increased water temperature) on ecosystem health. It also means adapting to large scale stressors, and reducing the potential for the cumulative impacts of multiple stressors, which can be much greater than any single stressor operating alone.

Objective 1.1: protect and maintain aquatic ecosystem diversity, connectivity, structure, and function, including fish habitat

Ontario’s fisheries depend on healthy aquatic ecosystems. Human activities such as urban development, shoreline or wetland alteration, dam construction, or resource extraction activities like mining or forestry can directly impact fish habitat and therefore the diversity, connectivity, structure and function of aquatic ecosystems. Fisheries can also impact aquatic ecosystems directly or indirectly by altering species composition, and thus the structure and function of the aquatic community. For example, selective removal of a particular top predator species or size of fish, or removal of non-target species (bycatch), can alter food web relationships and create conditions that allow the invasion of non-native species or disease pathogens. Understanding ecosystem structure and function therefore helps to develop appropriate strategies to avoid or mitigate impacts.

Connectivity is integral to the structure and function of aquatic ecosystems, and is a primary consideration in achieving healthy and sustainable fisheries. However, where landscapes are disturbed and aquatic systems stressed by invasive species and impaired water quality, restoration of connectivity may not be sufficient to achieve desirable ecological conditions. In some cases, it may be necessary to block connectivity to protect fisheries, for instance with the placement of Sea Lamprey barriers.

The tactics for Objective 1.1 focus on conserving the diversity, connectivity, structure and function of Ontario’s aquatic ecosystems through landscape-level planning and related activities. They are intended to encourage consideration of fish community structure and fish habitat in fisheries management decisions, and in preventing and mitigating the impacts of land-based activities on aquatic ecosystems.

Tactics

- Continue to implement existing, and where necessary develop new, legislation and policies that protect fish and fish habitat, and aquatic ecosystem structure and function.

- Promote the consideration of aquatic ecosystem and fish habitat protection objectives in government programs, policies and decisions.

- Account for the potential ecosystem effects of fishing such as community imbalance when planning and implementing fisheries management actions.

- Continue, and look for new opportunities, to incorporate aquatic ecosystem protection objectives into planning for land use, forest management, other resource management activities, and watershed planning at appropriate scales.

- Support the review and assessment of proposed development projects that may pose risk to fish communities, habitats and ecosystems, for example as part of environmental assessment processes.

- Protect Ontario’s diversity of aquatic ecosystems within National Parks and Provincial Parks and Protected Areas, and through land securement and stewardship partnerships.

- Develop an aquatic ecosystem classification system for Ontario, to provide a framework for conservation and management.

- Continue to identify and protect aquatic natural heritage systems, features and values.

Objective 1.2: protect the composition of native fish communities

Objective 1.2 is intended to protect the distribution, status, and genetic diversity of native fish species, populations and communities across the landscape. Ontario supports a wide variety of fish communities, reflecting the province’s geology, climate, and post-glacial colonization. Some fish communities are very simple, as in some northern Ontario lakes; others are very complex, as in southern Ontario streams and the Great Lakes. Species diversity reflects a rich variety of structures, processes and functions within an ecosystem that contributes to ecosystem resilience. Genetic diversity within a population of organisms helps the population to adapt to changing environmental conditions and thus remain viable over time. In order to maintain ecosystem resilience, ecosystem components that have a disproportionate influence or importance (keystone species, keystone ecosystems, or keystone processes) should be retained on the landscape.

Stocking of artificially propagated fish and the transfer of wild fish have played an important role in fisheries management in Ontario. While sometimes necessary to achieve fisheries management goals, stocking carries ecological risks, including the potential for loss of genetic integrity in native fish stocks and changes to community structure, such as the predator- prey balance.

Tactics under Objective 1.2 are geared to improving knowledge about native species, and implementing actions that protect native fish communities and gene pools.

Tactics

- Improve knowledge of the distribution and status of native fish communities and their habitats across Ontario through inventory, monitoring, research and classification.

- Where conservation concerns exist, proactively develop and implement species-specific policies and plans to protect and manage native fish species, through collaborative

- Develop and use fisheries management techniques that protect native species and gene pools, for example guidelines for brood stock or egg collection that protect genetic diversity.

Objective 1.3: restore, recover or rehabilitate degraded fish populations and their supporting ecosystems, including fish habitat

Many aquatic ecosystems, especially in southern Ontario, are degraded and require rehabilitation or restoration. Developing and implementing rehabilitation plans is a challenging task, and requires that MNRF encourage and work with partners including government agencies, Conservation Authorities, industry, academics, First Nations and Métis communities, and stakeholders. Recovery and rehabilitation objectives are often established through planning, such as species at risk recovery and management planning, and watershed and watershed- based fisheries management planning. Great Lakes Areas of Concern may also have their own specific rehabilitation objectives. In some cases, recovery and rehabilitation objectives and actions must be balanced across multiple species, although efforts directed at a single species often have benefits for others. Tactics to achieve Objective 1.3 emphasize continued restoration or rehabilitation of native fish communities, particularly of species at risk and the ecosystems that support them.

Tactics

- Develop and implement rehabilitation or restoration plans for degraded native fish populations and fish habitats, through collaborative

- Operate a fish culture program that supports the rehabilitation of native fish populations.

- Develop and implement recovery and management plans for aquatic species at risk and their habitat.

- Review and update provincial fisheries policies and management practices that may affect the recovery of species at risk.

Objective 1.4: prevent unauthorized introductions and slow the spread of invasive fish and other aquatic species, including pathogens

The intent of Objective 1.4 is to curb the introduction and spread of aquatic alien species, particularly those that are invasive. Fish community changes can be caused by intentional or unintentional introductions of species through activities such as unauthorized stocking, release of live bait and movement of boats and gear between water bodies.

The Ontario government has been involved in aquatic invasive species prevention and management activities since the early 1990s. Although there are many examples where these efforts have been effective, species continue to arrive and spread in Ontario. New approaches and tactics are required to address the current and future threats. In 2012, the Ontario government released the Ontario Invasive Species Strategic Plan, highlighting work that has already been undertaken and identifying gaps in current programs and policies. Since the release of the plan, MNRF has examined how Ontario’s existing legislation and policy framework addresses invasive species. This analysis clearly identified the need for a stronger legislative framework. In response, the government has drafted an Invasive Species Act, the first of its kind in Canada. The proposed Act will provide a stronger legislative framework to prevent, detect, rapidly respond, and manage invasive species that impact Ontario’s aquatic ecosystems.

Tactics under Objective 1.4 focus on prevention, early detection, rapid response, and management of aquatic invasive species as prescribed in the Ontario Invasive Species Strategic Plan. They also encourage better understanding of fish health, as a basis for managing the spread of invasive pathogens and other causes of disease outbreaks.

Tactics

- Implement actions related to the prevention, early detection, rapid response and effective management of aquatic invasive species (AIS), including supporting the regulation of species under the proposed Invasive Species Act or other regulatory tools as appropriate.

- Work with other agencies, academia, stakeholders, First Nations and Métis communities, and the private sector on fish disease surveillance, control, prevention and research, and define roles and responsibilities for managing fish health.

- Develop and implement best management practices to mitigate the risk of spreading alien species and pathogens through fisheries management actions.

Objective 1.5: anticipate and mitigate or adapt to large scale environmental changes and minimize cumulative environmental effects