Quackgrass

Learn about the history, habitat, benefits and control of quackgrass.

Introduction

Quackgrass, also commonly known as couch grass, twitch grass, quick grass, scutch grass, and devil's grass, is a widespread and serious weed in Canada. Traditionally one of the most difficult weeds to control, it remains a problem due to characteristics that enable it to survive and multiply: rapid establishment, an extensive mat of underground rhizomes with the ability to produce new plants, and the ease with which new quackgrass biotypes can be generated through sexual reproduction.

History

Quackgrass is native to Europe and Western Asia. It is thought to have moved from its centre of origin when it became a weed in cereal crops and then followed man's movement around the world. Today, it is often considered one of the three most serious weeds because it infests 37 different crops in 65 countries.

The first written account of quackgrass in Canada was in 1861, although it is likely that the weed had been present since Europeans first sowed cereal crops in Canada. By 1923 quackgrass was considered one of the three worst weeds in Eastern Canada. Today, it can be found in all of the provinces as well as the Northwest Territories. A recent survey estimated that 17.8 million hectares (44 million acres) or 56% of Canadian farmland has quackgrass present.

Habitat

Quackgrass is known as a temperate or cool season grass. In the spring and fall, it grows vigorously by producing as much as 2.5 cm of new rhizome growth per day. It is commonly found in fine-textured soils with a neutral to slightly alkaline soil pH (pH 6.5 to 8.0) and moderate soil moisture. It has also been observed in sandy, acidic soils. Quackgrass is fairly drought tolerant and it can withstand high quantities of salt.

Common to open areas, it is not found under conditions of continuous shade. Quackgrass can make up more than 90% of the biomass of an abandoned field; however, as shrubs and bushes begin to invade an area, it gradually become less prominent until it is eliminated.

Description

Quackgrass is a long-lived perennial that is capable of vegetative propagation via rhizomes and reproduction by seeds. It is considered to be self-sterile and relies primarily on wind for cross-pollination. Flowering occurs in late June to July and the seeds mature in early August to September. Commonly, 25 to 40 seeds per stem are produced in green to bluish-green spikes which are 5 to 30 cm in length. Seeds drop in late September where they overwinter in the leaf litter or on the ground. The seeds can remain viable for 1 to 6 years. Viability can be maintained even after passing through the digestive tract of most farm animals, except swine.

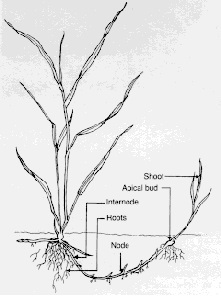

The rhizomes are slender (1.5 to 5 mm), smooth, pale white to straw-coloured, underground stems.

Nodes, from which secondary rhizomes or shoots may arise, are present along the length of the rhizome. Typically, shoots are stimulated to form when the terminal bud is severed from the rest of the rhizome (i.e. through tillage). The terminal bud produces various hormones that prevent other buds along the rhizome from forming new shoots. However, once it is removed new shoots can generate. It has been reported that one quackgrass plant produced 154 m of rhizomes and 206 shoots.

Leaves are typically 9 to 10 mm wide, 6 to 20 cm long and finely pointed. They are flat, pale yellow to green in colour with a very fine growth of hairs on the upper surface and a smooth lower surface. The leaf sheaths are round, split, and have overlapping margins. Ligules are short (0.5 to 1 mm), obtuse and membraneous. Auricles, fine projections at the leaf-node junction, clasp the stem. Stems are hollow, round and slender with 3 to 5 nodes; stem length varies from 30 to 120 cm.

Economic significance

Due to its highly competitive nature, quackgrass can effectively reduce crop yields by as much as 25% to 85% in corn, 19% to 55% in soybeans, and up to 57% in wheat.

These yield reductions may result from quackgrass' luxurious use of nutrients. It is estimated that quackgrass can absorb approximately 55%, 45%, and 68% of the total nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium, respectively, available for plant use.

In addition to yield losses, the presence of quackgrass seed or rhizomes can affect the quality of the crop. For grass seed producers, contamination of the crop with quackgrass seed can greatly reduce the value of the grass seed. Rhizomes are fairly flexible and they can grow through many underground structures, such as potato tubers, thereby reducing the marketability of the product. Also, in a corn field, an infestation of quackgrass can delay silking, tasselling, and slow grain dry down at harvest.

Quackgrass acts as a host for various pests. It can be infected with various cereal diseases such as leaf rusts, smuts, ergot, take-all, and strawbreaker. Some insect pests such as armyworm and cereal leaf beetle use quackgrass as an alternate or intermediate host to cereals.

Benefits

Although quackgrass can cause extensive crop losses, it does have some redeeming qualities. Quackgrass can be used for pasture or hay. Harvested at the same growth stage, quackgrass has a total (dry) crude protein content comparable to timothy. With its dense mat of rhizomes and roots, quackgrass efficiently binds soil on embankments and slopes, actively reducing soil erosion.

Research has indicated that quackgrass is one of the most effective plants for reclaiming nutrients, such as nitrogen, from sewage effluent sprayed on vegetation.

Certain natural chemicals extracted from quackgrass have been found to have insecticidal properties against mosquito larvae and molluscs, particularly slugs. Finally, the rhizomes can be dried and ground up for teas or used as a flour source.

Control

Control of quackgrass is dependent upon an understanding of the biology and the regenerative potential of rhizomes. The capacity for shoot regeneration from rhizomes increases with increased carbohydrate and nitrogen reserves. These reserves are generally highest in the fall and lowest at the time of quackgrass flowering. Fluctuations in these nutrients throughout the growing season will influence quackgrass control. Rhizome bud activity generally declines from mid-April to June. Buds remain dormant until early July when growth is once again initiated. This dormancy period also coincides with rapid shoot and rhizome production.

Fall tillage with either a moldboard plough or a soil saver is more effective in reducing the total amount of rhizomes present in the soil than spring tillage. Tillage also changes the distribution of rhizomes within the soil profile. In no-till, rhizomes are concentrated close to the soil surface, whereas with moldboard ploughing they are more uniformly distributed throughout the plough layer. The deeper the rhizomes within the soil profile the more uneven the emergence pattern of the shoots, thereby affecting the level of control achieved by selective herbicides. Specific recommendations for herbicide control are outlined in OMAFRA Publication 75, Guide to Weed Control.