Round-leaved Greenbrier recovery strategy

Read the recovery strategy for the Round-leaved Greenbrier, a plant species at risk in Ontario.

Download the Round-leaved Greenbrier recovery strategy (PDF)

Photo credit: Michael Oldham

About the Ontario recovery strategy series

This series presents the collection of recovery strategies that are prepared or adopted as advice to the Province of Ontario on the recommended approach to recover species at risk. The Province ensures the preparation of recovery strategies to meet its commitments to recover species at risk under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA) and the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk in Canada.

What is recovery?

Recovery of species at risk is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened, or extirpated species is arrested or reversed, and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of a species’ persistence in the wild.

What is a recovery strategy?

Under the ESA a recovery strategy provides the best available scientific knowledge on what is required to achieve recovery of a species. A recovery strategy outlines the habitat needs and the threats to the survival and recovery of the species. It also makes recommendations on the objectives for protection and recovery, the approaches to achieve those objectives, and the area that should be considered in the development of a habitat regulation. Sections 11 to 15 of the ESA outline the required content and timelines for developing recovery strategies published in this series.

Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for endangered and threatened species within one or two years respectively of the species being added to the Species at Risk in Ontario list. Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for extirpated species only if reintroduction is considered feasible.

What’s next?

Nine months after the completion of a recovery strategy a government response statement will be published which summarizes the actions that the Government of Ontario intends to take in response to the strategy. The implementation of recovery strategies depends on the continued cooperation and actions of government agencies, individuals, communities, land users, and conservationists.

For more information

To learn more about species at risk recovery in Ontario, please visit the Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks Species at Risk webpage.

Recommended citation

Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks. 2018. Recovery Strategy for the Round-leaved Greenbrier (Smilax rotundifolia) in Ontario. Ontario Recovery Strategy Series. Prepared by the Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks, Peterborough, Ontario. v + 12 pp. + Appendix. Adoption of the Round-leaved Greenbrier (Smilax rotundifolia) in Canada (Environment Canada 2017).

© Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2018

ISBN 978-1-4868-2760-2 (HTML)

ISBN 978-1-4868-2761-9 (PDF)

Content (excluding the cover illustration) may be used without permission with appropriate credit to the source, except where use of an image or other item is prohibited in the content use statement of the adopted federal recovery strategy.

Cette publication hautement spécialisée « Recovery strategies prepared under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 », n’est disponible qu’en anglais en vertu du Règlement 411/97 qui en exempte l’application de la Loi sur les services en français. Pour obtenir de l’aide en français, veuillez communiquer avec recovery.planning@ontario.ca.

Acknowledgment

The Ministry gratefully acknowledges Paul O’Hara (Blue Oak Native Landscapes), and Albert Garofalo (consulting botanist, Niagara Region) for information and insights regarding the recovery of Round-leaved Greenbrier in Ontario.

Declaration

The recovery strategy for the Round-leaved Greenbrier was developed in accordance with the requirements of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA). This recovery strategy has been prepared as advice to the Government of Ontario, other responsible jurisdictions and the many different constituencies that may be involved in recovering the species.

The recovery strategy does not necessarily represent the views of all of the individuals who provided advice or contributed to its preparation, or the official positions of the organizations with which the individuals are associated.

The recommended goals, objectives and recovery approaches identified in the strategy are based on the best available knowledge and are subject to revision as new information becomes available. Implementation of this strategy is subject to appropriations, priorities and budgetary constraints of the participating jurisdictions and organizations.

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this strategy.

Responsible jurisdictions

Ontario Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks

Environment and Climate Change Canada – Canadian Wildlife Service, Ontario

Parks Canada Agency

Executive summary

The Endangered Species Act, 2007(ESA) requires the Minister of the Environment, Conservation and Parks to ensure recovery strategies are prepared for all species listed as endangered or threatened on the Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) List. Under the ESA, a recovery strategy may incorporate all or part of an existing plan that relates to the species.

The Round-leaved Greenbrier (Smilax rotundifolia) is listed as threatened on the SARO List. The Great Lakes Plains population of the species is listed as threatened under the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA). Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) prepared the Recovery Strategy for the Round-leaved Greenbrier (Smilax rotundifolia), Great Lakes Plains population, in Canada in 2017 to meet its requirements under the SARA. This recovery strategy is hereby adopted under the ESA. With the additions indicated below, the enclosed strategy meets all of the content requirements outlined in the ESA.

Updated information is provided on Round-leaved Greenbrier’s distribution and abundance in Ontario, the biophysical attributes of its habitat and the threats that it is known to face in the province.

The Critical Habitat section of the federal recovery strategy provides an identification of critical habitat (as defined under the SARA). Identification of critical habitat is not a component of a recovery strategy prepared under the ESA. However, it is recommended that the approach used to identify critical habitat in the federal recovery strategy be considered along with any new scientific information on Round-leaved Greenbrier and its habitat, including the information under “Habitat needs” below, when developing a habitat regulation under the ESA.

Adoption of federal recovery strategy

The Endangered Species Act, 2007(ESA) requires the Minister of the Environment, Conservation and Parks to ensure recovery strategies are prepared for all species listed as endangered or threatened on the Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) List. Under the ESA, a recovery strategy may incorporate all or part of an existing plan that relates to the species.

The Round-leaved Greenbrier (Smilax rotundifolia) is listed as threatened on the SARO List. The Great Lakes Plains population of the species is also listed as threatened under the federal Species at Risk Act(SARA). Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) prepared the Recovery Strategy for the Round-leaved Greenbrier (Smilax rotundifolia), Great Lakes Plains population, in Canada in 2017 to meet its requirements under the SARA. This recovery strategy is hereby adopted under the ESA. With the additions indicated below, the enclosed strategy meets all of the content requirements outlined in the ESA.

Species assessment and classification

Table 1. Species assessment and classification of the Round-leaved Greenbrier (Smilax rotundifolia).

The glossary provides definitions for the abbreviations within, and for other technical terms in this document.

| Assessment | Status |

|---|---|

| SARO List classification | Threatened |

| SARO List history | Threatened (2001), Vulnerable (1995) |

| COSEWIC assessment history | Great Lakes Plains population: Threatened (2007), Threatened (2001), Threatened (1994); Atlantic population: Not at Risk (2007) |

| SARA schedule 1 | Threatened (Great Lakes Plains population) |

| Conservation status rankings | GRANK: G5 NRANK: N3 SRANK: S2 |

Distribution, abundance and population trends

As a result of field investigations during the summer and autumn of 2017 and the winter of 2017/18, 13 populations of Round-leaved Greenbrier were reconfirmed, including a population in the Niagara Region not reported in ECCC (2017) (local population no. 18 in Table 2). Updated information was obtained on the size, extent and sexual condition of these populations. This information is summarized in Table 2, based on O’Hara (2018a, b) and adapted from Table 1 in ECCC (2017).

Table 2. Populations of Round-leaved Greenbrier, Great Lakes Plains population , with updates to last observation dates, sex status at last observation, and abundance based on O’Hara (2018a, b) and ECCC (2017).

| Local Population No. | Local Population Name | Last Obs. | Status | Sex Status at last Obs. | Abundance | Land Ownership and Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cedar Creek ESA |

1984 | Historical; presumed extant | Unknown |

20-30 crowns |

Essex Region Conservation Authority and private |

| 2 | Catbrier Woods ESA | 2017 | Extant | Unknown (Male only in 1990) | Patch 50 x 50 m with thousands of stems (Only southern third of treed area accessed. Therefore two other subpopulations not observed.) | Private |

| 3 | White Oak Woods ESA | 1989 | Historical; presumed extant | Male and female | ~ 50 crowns, some fruiting | Private |

| 4 | Sweetfern Woods ESA | 2017 | Extant | Unknown (Male only in 1989) | Two patches, 50 x 50 and 10 x 5 m, with hundreds of stems in total (Only western third of treed area accessed.) | Private |

| 5 | Blytheswood ESA | 2017 | Extant | Male and female (Male and female in 1982) | 15 patches from 1 x 1 to 20 x 15 m, over half ³ 5 x 10 m, with over a thousand stems in total | Private |

| 14 | Point Pelee | 1881 | Extirpated | Extirpated | No information | Extirpated (COSEWIC 2007). Based on a specimen in CAN by Macoun. Never relocated. |

| Local Population No. | Local Population Name | Last Obs. | Status | Sex Status at last Obs. | Abundance | Land Ownership and Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | South Walsingham Sand Ridges | 2018 | Extant | Male and female | 23 patches from 1 x 1 to 100 x 100 m over half >= 10 x 15 m, with several thousand stems in total | Long Point Region Conservation Authority, Nature Conservancy of Canada and private |

| Local Population No. | Local Population Name | Last Obs. | Status | Sex Status at last Obs. | Abundance | Land Ownership and Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | South Walsingham Sand Ridges | 2018 | Extant | Male and female | 23 patches from 1 x 1 to 100 x 100 m over half >= 10 x 15 m, with several thousand stems in total | Long Point Region Conservation Authority, Nature Conservancy of Canada and private |

|

7 |

Drummond Heights |

2017 |

Extant |

Male and female (Male and female in 2006) |

Patch 16 x 18 m with hundreds of stems and two smaller patches, 5 x 5 and 2 x 2 m, with about 23 stems |

Private |

|

8 |

Garner Road A Edgewood Woodlot |

2017 |

Extant |

Unknown (Female only in 2006) |

Patch 30 x 20 m with hundreds of stems, second 1 x 1 m patch with two stems |

City of Niagara Falls |

|

9 |

Cooks Mills |

2018 |

Extant |

Unknown |

Two patches, 20 x 30 and 30 x 30 m, each with hundreds of stems |

Private |

|

10 |

Fenwick |

2017 |

Extant |

Unknown |

17 patches from 3 x 1 to 40 x 80 m, over half >= 20 x 20 m, with several thousand stems in total (Northernmost part of property not accessed.) |

Private |

|

11 |

Lyons Creek North |

2017 |

Extant |

Unknown (Male only in 2007) |

Five patches 10 x 5, 5 x 5, 10 x 30, 15 x 15 and 10 x 10 m with ~100, ~ 25, 100s, ~100 and ~100 stems respectively (Northwest part of property not surveyed.) |

Private |

|

12 |

Woodlawn Park |

2017 |

Extant |

Unknown |

Five patches 3 x 3, 6 x 12, 10 x 8, 12 x 30 and 2 x 2 m with 4, 75, 25, 200 and 9 stems respectively. Total of 313 |

City of Welland |

|

13 |

Garner Road B Fernwood |

2017 |

Extant |

Unknown: info not reported |

Patch 35 x 18 m with hundreds of stems |

City of Niagara Falls |

|

15 |

Bowman’s Woods West |

2013 |

Extant |

Unknown |

Two patches, each with 50-100 stems |

City of Niagara Falls |

|

16 |

Heartland Forest |

2017 |

Extant |

Unknown |

Patch 8 x 10 m with 30 stems |

Private nature centre |

|

17 |

McCleod Road |

1980 |

Historical; presumed extant |

Unknown: info not reported |

No information |

Private |

|

18 |

Boyer’s Creek north of Sherk Road |

2017 |

Extant |

Male and female |

Patch 8 x 8 m with 75 stems |

Public |

Habitat needs

More information on the habitat of Round-leaved Greenbrier has been obtained since the publication of ECCC (2017). ECCC (2017) names two ecological communities of which Round-leaved Greenbrier is a component in Essex County and lists several trees and shrubs reported to be associated with Round-leaved Greenbrier in Ontario. O’Hara (2018a) provides an expanded list of associated Ontario plant species, including herbaceous plants. He also supplies additional names of ecological communities to which Round-leaved Greenbrier belongs in Ontario. The additional communities have been determined in accordance with the methods of Lee et al. (1998) by P. O’Hara, A. Garofalo and B. Draper between 2011 and 2017 (see O’Hara 2018a). Table 3 presents the names and ecological land classification codes of communities in which Round-leaved Greenbrier has been documented; Table 4 provides a list of associated plants within three different forest strata.

Table 3. Ecological land classification codes and community names in which Round-leaved Greenbrier has been documented in Ontario.

| Community Code | Community Name |

|---|---|

| SWD2-2 | Green Ash Mineral Deciduous Swamp Type |

| SWD4-4 | Yellow Birch-Poplar Mineral Deciduous Swamp Type |

| SWD6-3 | Silver Maple Organic Deciduous Swamp Type |

| SWD7-2 | Yellow Birch Organic Deciduous Swamp Type |

| FOD6-3 | Fresh-Moist Sugar Maple-Yellow Birch Deciduous Forest Type |

| FOD8-1 | Fresh-Moist Poplar Deciduous Forest Type |

| FOD9-2 | Fresh-Moist Oak-Maple Deciduous Forest Type |

The contents of Table 3 are not likely representative of all ecological communities that Round-leaved Greenbrier inhabits in Ontario. O’Hara (2018a) presents evidence that forested dunes were occupied by Round-leaved Greenbrier historically in Essex County.

Table 4. List of associated plants within three different forest strata documented by O’Hara (2018a). For additional associated plants, see Table 2 and Appendix B of ECCC (2017).

| Forest stratum | Species Names |

|---|---|

| Canopy | Red Oak (Quercus rubra), White Oak (Quercus alba), Bur Oak (Quercus macrocarpa), Swamp Pin Oak (Quercus palustris) (Niagara and Windsor-Essex), Black Cherry (Prunus serotina), Red Maple (Acer rubrum), Sugar Maple (Acer saccharum), American Beech (Fagus grandifolia), White Ash (Fraxinus americana), Red Ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica), White Elm (Ulmus americana), Shagbark Hickory (Carya ovata), Silver Maple (Acer saccharinum), Tulip Tree (Liriodendron tulipifera), Yellow Birch (Betula alleghaniensis), Black Gum (Nyssa sylvatica), Sassafras (Sassafras albidum). |

| Sub-canopy/Shrub Layer | Northern Spicebush (Lindera benzoin), American Witch-hazel (Hamamelis virginiana), Maple-leaved Viburnum (Viburnum acerifolium), Blue-beech (Carpinus caroliniana), Serviceberry species (Amelanchier spp.), Highbush Blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum), Eastern Buttonbush (Cephalanthus occidentalis), Common Winterberry (Ilex verticillata), Ash species (Fraxinus spp.), Eastern Hop-hornbeam (Ostrya virginiana), White Elm (Ulmus americana), Red Maple (Acer rubrum). |

| Ground Layer | Broad-leaved Enchanter’s Nightshade (Circaea canadensis), Virginia Smartweed (Persicaria virginiana), Large-leaved Aster (Eurybia macrophylla), Spotted Jewelweed (Impatiens capensis), Hairy Solomon’s Seal (Polygonatum pubescens), Rough-stemmed Goldenrod (Solidago rugosa), Blue-stemmed Goldenrod (Solidago caesia), Large False Solomon’s Seal (Maianthemum racemosum), Wild Lily-of-the-valley (Maianthemum canadense), Calico Aster (Symphyotrichum lateriflorum), Fowl Mannagrass (Glyceria striata), Stout Woodreed (Cinna arundinacea), Poison Ivy species (Toxicodendron spp.), Royal Fern (Osmunda regalis), Cinnamon Fern (Osmundastrum cinnamomeum), Bracken Fern (Pteridium aquilinum), Sensitive Fern (Onoclea sensibilis), Shield Fern species (Dryopteris spp.), Fringed Sedge (Carex crinita), Bladder Sedge (C. intumescens), Pennsylvania Sedge (C. pennsylvanica), Graceful Sedge (C. gracillima), Sedge species (Carex spp.) (Ovales group). |

Threats to survival and recovery

As a result of field investigations during the summer and autumn of 2017 and the winter of 2017/18, threats to Round-leaved Greenbrier not mentioned in ECCC (2017) have been identified in O’Hara (2018a). These are summarized below:

(1) In some areas of Ontario habitat encroachment and incidental damage has been found to be a current threat to Round-leaved Greenbrier. Incidental damage to plants has resulted from the maintenance of hydro right-of-ways and the cutting of stems that sucker into fields maintained for crop production. Round-leaved Greenbrier and its habitat have also been negatively affected as a result of dumping of excavated soil.

(2) In Essex County, Norfolk County, and the Niagara Region, where the natural disturbance regime has been altered due to human settlement, Round-leaved Greenbrier has been found in closed-canopy forested settings. Given that the species flourishes most-readily in forest openings and edge situations (COSEWIC 2007), canopy suppression, i.e., excessive shading of the vines from the canopy due to a lack of natural disturbance, has been found to be a current and widespread threat to the species in Ontario. It was observed at five occurrences in the Niagara Region and two in Essex County and at numerous sub-occurrences within the Norfolk County occurrence (O’Hara 2018b). At one excessively shaded occurrence in the Niagara Region with male and female plants present, no dispersal and establishment were observed in spite of the production of fruit. In contrast, at a sexually-reproducing occurrence in Essex Region and a sexually-reproducing sub-occurrence in Norfolk County, where the forest had been recently thinned, many new young patches of Round-leaved Greenbrier were found (O’Hara 2018a). At some sites, shading also appeared to affect vine height. For example, at a Norfolk County sub-occurrence, where excessive shading was observed, vines were 1-5 m in height (mean = 2.75 m) while they were 7-10 m (mean = 8.5 m) where shading was not identified as a threat (O'Hara 2018b).

(3) ECCC (2017) identifies Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata), Glossy Buckthorn (Frangula alnus), and Tartarian Honeysuckle (Lonicera tatarica) as invasive plant species that may compete with Round-leaved Greenbrier. Recent field investigations provide evidence that Multiflora Rose (Rosa multiflora) is a current threat of high severity and level of concern in Norfolk County. Glossy Buckthorn is establishing at a site in the City of Niagara Falls where illegal dumping occurred in the summer of 2017. At another Niagara Falls site, Honeysuckle, European Common Reed (Phragmites australis ssp. australis) and European Buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica) are invading.

Round-leaved Greenbrier is also affected by potentially problematic native species. In Norfolk County, it was found to be host to Turbulent Phosphila (Phosphila turbulenta). The caterpillar of this moth feeds exclusively on Greenbrier (Smilax) species and was found infesting Round-leaved Greenbrier vines. In the Niagara Region, Riverbank Grape (Vitis riparia) is competing with Round-leaved Greenbrier in at least one site.

In addition to facing the threats mentioned above, Round-leaved Greenbrier appears to be limited by lack of sexual reproduction. Approximately a fifth of its occurrences are presumed to be a single sex. Only five occurrences are known to be reproducing sexually, but within these populations the sexual condition of many patches is unknown. Clonal reproduction may predominate, potentially resulting in inbreeding depression.

Recovery actions completed or underway

Surveys have been completed to re-confirm the presence of Round-leaved Greenbrier at several locations from the summer of 2017 through the winter of 2018.

Approaches to recovery

The federal recovery strategy does not include recovery actions to address a number of the threats identified during the 2017 and 2018 field seasons. These include habitat encroachment and incidental harm to Round-leaved Greenbrier, canopy suppression due to loss of natural disturbance and problematic native species that feed on or compete with Round-leaved Greenbrier. Consideration should be given to relevant recovery actions that would help to address these threats when developing recovery initiatives for this species in Ontario.

Area for consideration in developing a habitat regulation

Under the ESA, a recovery strategy must include a recommendation to the Minister of the Environment, Conservation and Parks on the area that should be considered in developing a habitat regulation. A habitat regulation is a legal instrument that prescribes an area that will be protected as the habitat of the species. The recommendation provided below will be one of many sources considered by the Minister, including information that may become newly available following completion of the recovery strategy, when developing the habitat regulation for this species.

The Critical Habitat section of the federal recovery strategy provides an identification of critical habitat (as defined under the SARA). Identification of critical habitat is not a component of a recovery strategy prepared under the ESA. However, it is recommended that the approach used to identify critical habitat in the federal recovery strategy be considered along with any scientific information on Round-leaved Greenbrier and its habitat, including the information under “Habitat needs” above, when developing a habitat regulation under the ESA.

Glossary

Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC): The committee established under section 14 of the Species at Risk Act that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Canada.

Committee on the Status of Species at Risk in Ontario (COSSARO): The committee established under section 3 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Ontario.

Conservation status rank: A rank assigned to a species or ecological community that primarily conveys the degree of rarity of the species or community at the global (G), national (N) or subnational (S) level. These ranks, termed G-rank, N-rank and S-rank, are not legal designations. Ranks are determined by NatureServe and, in the case of Ontario’s S-rank, by Ontario’s Natural Heritage Information Centre. The conservation status of a species or ecosystem is designated by a number from 1 to 5, preceded by the letter G, N or S reflecting the appropriate geographic scale of the assessment. The numbers mean the following:

- 1 = critically imperilled

- 2 = imperilled

- 3 = vulnerable

- 4 = apparently secure

- 5 = secure

- NR = not yet ranked

Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA): The provincial legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Ontario.

Species at Risk Act (SARA): The federal legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Canada. This act establishes Schedule 1 as the legal list of wildlife species at risk. Schedules 2 and 3 contain lists of species that at the time the Act came into force needed to be reassessed. After species on Schedule 2 and 3 are reassessed and found to be at risk, they undergo the SARA listing process to be included in Schedule 1.

Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) List: The regulation made under section 7 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that provides the official status classification of species at risk in Ontario. This list was first published in 2004 as a policy and became a regulation in 2008.

References

COSEWIC. 2007. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the round-leaved greenbrier (Great Lakes Plains and Atlantic population) Smilax rotundifoliain Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 32 pp.

Environment and Climate Change Canada. 2017. Recovery Strategy for the Round-leaved Greenbrier (Smilax rotundifolia), Great Lakes Plains population, in Canada. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Environment and Climate Change Canada, Ottawa. vii + 36 pp.

Lee, H., W. Bakowsky, J. Riley, J. Bowles, M. Puddister, P. Uhlig and S. McMurray. 1998. Ecological Land Classification for Southern Ontario – First Approximation and its application. SCSS Field Guide FG-02.

O’Hara, P. 2018a. 2017 Round-leaved Greenbrier (Smilax rotundifolia) Survey SARSF_12_17_BONL – Final Report. Prepared for MNRF under SAR Stewardship Fund.

O’Hara, P. 2018b. 2017 Round-leaved Greenbrier (Smilax rotundifolia) Survey SARSF_12_17_BONL – Data Tabulation. Prepared for MNRF under SAR Stewardship Fund.

List of abbreviations

- COSEWIC

- Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada

- COSSARO

- Committee on the Status of Species at Risk in Ontario

- ESA

- Ontario’s Endangered Species Act, 2007

- ISBN

- International Standard Book Number

- OMNRF

- Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry

- SARA

- Canada’s Species at Risk Act

- SARO

- Species at Risk in Ontario

Appendix 1. Recovery strategy for the Round-leaved Greenbrier (Smilax rotundifolia) in Canada

Federal cover illustration: R. Schipper, Michigan Flora Online

Document information

Recommended citation:

Environment and Climate Change Canada. 2017. Recovery Strategy for the Round-leaved Greenbrier (Smilax rotundifolia), Great Lakes Plains population, in Canada. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Environment and Climate Change Canada, Ottawa. vii + 36 pp.

Other document information

For copies of the recovery strategy, or for additional information on species at risk, including the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) Status Reports, residence descriptions, action plans, and other related recovery documents, please visit the Species at Risk (SAR) Public Registry.

Également disponible en français sous le titre« Programme de rétablissement du smilax à feuilles rondes (Smilax rotundifolia), population des plaines des Grands Lacs, au Canada »

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of Environment and Climate Change, 2017. All rights reserved.

ISBN 978-0-660- 24219-4

Catalogue no. En3-4/271-2017E-PDF

Content (excluding the illustrations) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source.

Preface

The federal, provincial, and territorial government signatories under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk (1996)

The Minister of Environment and Climate Change is the competent minister under SARA for the Round-leaved Greenbrier, Great Lakes Plains population, and has prepared this recovery strategy, as per section 37 of SARA. To the extent possible, it has been prepared in cooperation with the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, as per section 39(1) of SARA.

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this strategy and will not be achieved by Environment and Climate Change Canada, or any other jurisdiction alone. All Canadians are invited to join in supporting and implementing this strategy for the benefit of the Round-leaved Greenbrier, Great Lakes Plains population, and Canadian society as a whole.

This recovery strategy will be followed by one or more action plans that will provide information on recovery measures to be taken by Environment and Climate Change Canada and other jurisdictions and/or organizations involved in the conservation of the species. Implementation of this strategy is subject to appropriations, priorities, and budgetary constraints of the participating jurisdictions and organizations.

The recovery strategy sets the strategic direction to arrest or reverse the decline of the species, including identification of critical habitat to the extent possible. It provides all Canadians with information to help take action on species conservation. When critical habitat is identified, either in a recovery strategy or an action plan, SARA requires that critical habitat then be protected.

In the case of critical habitat identified for terrestrial species including migratory birds SARA requires that critical habitat identified in a federally protected area

For critical habitat located on other federal lands, the competent minister must either make a statement on existing legal protection or make an order so that the prohibition against destruction of critical habitat applies.

If the critical habitat for a migratory bird is not within a federal protected area and is not on federal land, within the exclusive economic zone or on the continental shelf of Canada, the prohibition against destruction can only apply to those portions of the critical habitat that are habitat to which the Migratory Birds Convention Act, 1994 applies as per SARA ss. 58(5.1) and ss. 58(5.2).

For any part of critical habitat located on non-federal lands, if the competent minister forms the opinion that any portion of critical habitat is not protected by provisions in or measures under SARA or other Acts of Parliament, or the laws of the province or territory, SARA requires that the Minister recommend that the Governor in Council make an order to prohibit destruction of critical habitat. The discretion to protect critical habitat on non-federal lands that is not otherwise protected rests with the Governor in Council.

Acknowledgments

Judith Jones (Winter Spider Eco-Consulting) drafted this recovery strategy, with supervision from Lauren Strybos (Canadian Wildlife Service – Ontario). Development of the recovery strategy was facilitated by Judith Girard, Marie-Claude Archambault and Karissa Reischke (Canadian Wildlife Service – Ontario). An earlier version of the document was prepared by Jarmo Jalava and the Carolinian Woodlands Recovery Team in 2007. The following people are gratefully acknowledged for sharing information on this species: John Ambrose (Cercis Consulting), Albert Garofalo (Niagara Falls Nature Club), David Holmes (Long Point Region Conservation Authority), Dan Lebedyk (Essex Region Conservation Authority), Amy Parks (Niagara Region Conservation Authority), and Joyce Sankey (Niagara Falls Nature Club). The recovery strategy benefited from input, review, and suggestions from the following individuals: Ken Corcoran, Angela McConnell, Christina Rohe, John Brett, and Lee Voisin (Canadian Wildlife Service – Ontario), Kim Borg (Canadian Wildlife Service), Eric Snyder, Jay Fitzsimmons, Leanne Jennings, Sam Brinker and Vivian Brownell (Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry). Albert Garofalo is thanked for providing photos of Round-leaved Greenbrier.

Acknowledgement and thanks is given to all other parties that provided advice and input used to help inform the development of this recovery strategy including various Indigenous organizations and individuals, individual citizens, and stakeholders who provided input and/or participated in consultation meetings.

Executive Summary

In Canada, Round-leaved Greenbrier (Smilax rotundifolia) occurs in Ontario (Great Lakes Plains population) and in southwestern Nova Scotia (Atlantic population). This recovery strategy addresses only the Great Lakes Plains population which is listed as Threatened under both Schedule 1 of SARA and the Ontario Endangered Species Act 2007 (ESA). The Atlantic population is listed as Not at Risk on Schedule 1 of the Species at Risk Act (SARA). NatureServe ranks the species as Vulnerable (N3) in Canada and Imperiled (S2) in Ontario, where it occurs in Essex and Norfolk Counties and in the Niagara Region. There are 16 known extant or presumed extant local populations and one extirpated local population in Ontario.

Round-leaved Greenbrier is a long-lived perennial vine with long stems that climb with tendrils up into trees or form tangles over the ground. At the base, the stems are woody, while above they are armed with stout prickles. The oval- to heart-shaped leaves are alternate and have arching parallel veins. The fruit is a berry eaten by birds and mammals, and dispersed in their droppings.

This genus is dioecious (male and female flowers on separate plants) and both male and female plants must be present for fruit production. Currently, at least four local populations in Ontario are thought to contain only one sex. The factors controlling which sex is expressed and the reason for biased sex ratios are not known. In Ontario, Round‑leaved Greenbrier is found in the understory and openings in moist to wet Carolinian forest. These forests have been described as Lowland Red Maple-Mixed Oak Forest or Mixed Oak Forest.

The primary threats to Round-leaved Greenbrier include residential, industrial, and commercial development, high-intensity logging, and alterations to the moisture regime. These threats can be addressed by standard land use planning, habitat stewardship and habitat protection measures. The level of risk posed by invasive species is unknown, but if necessary can be addressed through best management practices (BMPs).

The population and distribution objectives are to: maintain the species’ distribution (including any new local populations that are discovered) and to maintain or, where necessary and technically and biologically feasible, increase abundance, at the 16 extant and presumed extant local populations. The broad strategies to be taken to address the threats to the survival and recovery of Round-leaved Greenbrier are presented in the section on Strategic Direction for Recovery (Section 6.2).

Critical habitat is identified as wooded area occupied by Round-leaved Greenbrier, including all contiguous wooded habitat around Round-leaved Greenbrier plants. Critical habitat identified for Round-leaved Greenbrier meets the population and distribution objectives, and a schedule of studies is not included. One or more action plans for Round-leaved Greenbrier will be completed by 2024.

Recovery Feasibility Summary

Based on the following four criteria that Environment and Climate Change Canada uses to establish recovery feasibility, there are unknowns regarding the feasibility of recovery of the Round-leaved Greenbrier, Great Lakes Plains population. In keeping with the precautionary principle, a recovery strategy has been prepared as per section 41(1) of SARA, as would be done when recovery is determined to be technically and biologically feasible. This recovery strategy addresses the unknowns surrounding the feasibility of recovery.

1. Individuals of the wildlife species that are capable of reproduction are available now or in the foreseeable future to sustain the population or improve its abundance.

Unknown. It is estimated there are 1000 to 5000 crowns (multi-stemmed clusters) of Round-leaved Greenbrier, Great Lakes Plains population, in Canada. However, it is unknown how many individual plants this represents, because with many stems per crown it can be difficult to distinguish one crown from another. COSEWIC (2007) estimated that there may be fewer than 250 individuals in Canada. Plants of this species are dioecious, meaning that each individual produces either only male or only female flowers at one time. Of the seven local populations for which information on sex status is available, only three are known to have both sexes present, and are therefore capable of sexual reproduction. The other four are thought to contain only a single sex, and are therefore only capable of vegetative reproduction. No seedlings of Round‑leaved Greenbrier have been reported in recent surveys (Ambrose 1994; COSEWIC 2007).

2. Sufficient suitable habitat is available to support the species or could be made available through habitat management or restoration.

Yes. The Great Lakes Plains population of Round-leaved Greenbrier is found in Ontario in moist to wet Carolinian forest. While Carolinian forest habitat is limited in Ontario due to historical harvesting, there are still remnant areas of suitable moist to wet forest in regions where Round-leaved Greenbrier occurs. Some are in conservation ownership and are protected from further land conversion. As well, there is additional unoccupied suitable habitat available in some forests where Round-leaved Greenbrier already occurs.

3. The primary threats to the species or its habitat (including threats outside Canada) can be avoided or mitigated.

Yes. The primary threat to the Great Lakes Plains population of Round-leaved Greenbrier is from habitat loss due to development. This can be curtailed through land use planning and by working with planning authorities, to prevent destruction of this plant’s Carolinian forest habitat. Other important threats include high-intensity logging and changes in moisture regimes, which can be mitigated by stewardship and protection of Round-leaved Greenbrier habitat. The level of risk posed by invasive species is unknown, but if invasive species prove problematic, they can be managed with standard best-management practices (BMPs).

4. Recovery techniques exist to achieve the population and distribution objectives or can be expected to be developed within a reasonable timeframe.

Yes. Standard techniques to reduce threats, such as habitat management, stewardship and protection, and the use of land use planning, policy, and outreach and education will help to protect existing local populations and individuals of Round-leaved Greenbrier, Great Lakes Plains population. Researching and implementing measures to establish sexually reproducing local populations will be necessary to improve resilience of the species. This may include augmenting single-sex local populations with individuals of the opposite sex, and researching factors influencing seedling survival.

1. COSEWIC* Species Assessment Information

Date of Assessment: November 2007

Common Name (population): Round-leaved Greenbrier - Great Lakes Plains population

Scientific Name: Smilax rotundifolia

COSEWIC Status: Threatened

Reason for Designation: The species is currently known from 13 highly fragmented populations in Ontario’s Carolinian Zone. Four populations have been found since the previous COSEWIC assessment due to more extensive surveys, and although no population was lost, habitat declines have occurred. Population size and trend are poorly known due to the clonal nature of the species. Many Ontario populations appear to have plants of only one sex and therefore cannot produce seed. The plants, however, are vigorous, long-lived and resistant to habitat changes.

Canadian Occurrence: Ontario

COSEWIC Status History: Designated Threatened in April 1994. Status re-examined and confirmed in May 2001 and November 2007.

2. Species Status Information

In Canada, Round-leaved Greenbrier (Smilax rotundifolia) occurs in Ontario (the Great Lakes Plains population) and also in southwestern Nova Scotia (the Atlantic population). The Atlantic population is assessed by COSEWIC as Not at Risk

3. Species Information

3.1. Species Description

Round-leaved Greenbrier is a perennial

Round-leaved Greenbrier may be confused in the field with Bristly Greenbrier (S. tamnoides), which is the only other woody greenbrier in southern Ontario. Round‑leaved Greenbrier may be identified by the widely spaced stout prickles on the stems, which are not bristly (Figure 2); by the stalk of the fruit cluster which is about as long as the leaf stalks but no longer; and by having usually fewer than 12 flowers or fruits in a cluster (Ambrose 1994; Holmes 2002).

Figure 1. Climbing habitat of Round-leaved Greenbrier showing a crown of many stems at the base. (Photo: Albert Garofalo).

Figure 2. Stem of Round-leaved Greenbrier showing stout prickles and no smaller bristles. (Photo: Albert Garofalo).

3.2 Species Population and Distribution

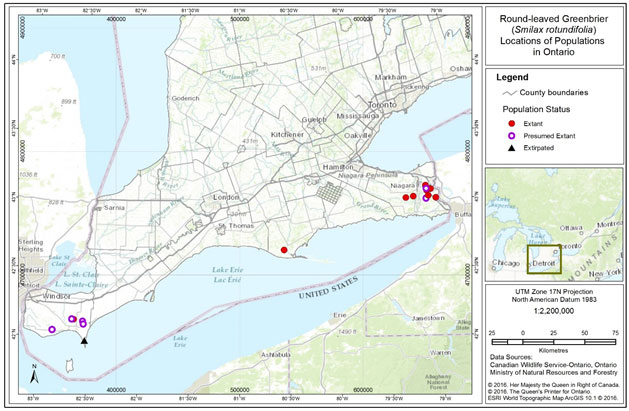

The Great Lakes Plains population of Round-leaved Greenbrier occurs only in southern Ontario in three regions: Essex County, Norfolk County, and in the Niagara Region (COSEWIC 2007) (Figure 3). In addition to this, Soper and Heimburger (1990) report the species as also known from Kent and Middlesex counties. However, reports from these two counties are unsubstantiated as no documented basis for these reports has been found (COSEWIC 2007; Oldham pers. comm. 2016). A specimen from 1895 collected from Morris Township, Huron County is listed in the database of Canadensys (2016) and housed in the herbarium of the University of British Columbia. It is labeled Smilax rotundifolia. A digital image of this specimen shows a plant with a bristly stem, no stout prickles, and long stalks to the flower clusters. This appears to be a specimen of Bristly Greenbrier (Smilax tamnoides) that has been misidentified (Oldham pers. comm. 2016). There is no evidence that Round-leaved Greenbrier was ever more abundant or widespread in Ontario (COSEWIC 2007).

A list of local Ontario populations and their locations is shown in Table 1. There are a total of 17 known local populations; ten extant, six historical

Three local populations listed in Table 1 were not known at the time of the last COSEWIC assessment (COSEWIC 2007). Bowman’s Woods West (local population # 15) and Heartland Forest (local population # 16) have been recently discovered by members of the Niagara Falls Nature Club (Garofalo pers. comm. 2016; Sankey pers. comm. 2016). It is likely that these local populations have existed for many years, but have only recently been observed and reported. McLeod Road (local population # 17), has been identified as a historical local population based on Natural Heritage Information Centre (NHIC) records (NHIC 2016). It is possible that additional local populations will be found in the future, but the limited amount of suitable habitat remaining for this species, and high rates of forest loss to urbanization in southern Ontario make it unlikely that a large number of unknown local populations exist in this region.

At the last status assessment, COSEWIC estimated that there are 1000 to 5000 crowns of Round-leaved Greenbrier in Canada. The three local populations found since that assessment are small relative to the variation in this estimate (Table 1, local populations # 15, 16 and 17), so the estimate of 1000 to 5000 crowns continues to be valid. However, it is uncertain how many individuals this may represent because with many stems per crown it can be difficult to distinguish one crown from another. COSEWIC (2007) estimated that there may be fewer than 250 genetically distinct individuals in Canada.

Ambrose (1994) hypothesized that the present Ontario distribution of Round-leaved Greenbrier reflects the likely paths of post-glacial migration of plant species across the two land bridges around Lake Erie, and that the current distribution of Round-leaved Greenbrier as isolated small patches is the result of a single dispersal event or only very few events. Why birds have not dispersed the species over a larger area is not known. No seedlings of Round-leaved Greenbrier have been seen in any surveys from the late 1980s to the present, so gene-flow from the U.S. to the Canadian population is unlikely.

In the U.S., Round-leaved Greenbrier is present from Maine south to Florida and west to Oklahoma and central Texas (Kartesz 2015; NatureServe 2015a). In the greater North American range, there is some discrepancy between the range NatureServe (2015a) shows for this species and the range shown by the Biota of North America Project (BONAP) (Kartesz 2015) and the Flora of North America (FNA) (Holmes 2002); BONAP and the FNA do not show the species as occurring in Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, or South Dakota, and BONAP does not show it as rare in Illinois. The North American distribution as shown in the FNA was taken as most correct by COSEWIC (2007).

Table 1. Local populations of Round-leaved Greenbrier, Great Lakes Plains population, with last observation, sex status at last observation, and land ownership.

| Local Population # |

Local Population Name | Last Obs. | Status | Sex status at last obs. | Abundance | Land Ownership and Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Essex County | ||||||

| 1 | Cedar Creek ESA | 1984 | Historical; presumed extant | Unknown: not flowering or fruiting | 20-30 crowns | Private and Essex Region Conservation Authority Not found in 2006, but only partial survey of large area. |

| 2 | Catbrier Woods ESA | 1990 | Historical; presumed extant | Male only | 12-16 crowns | Private |

| 3 | White Oak Woods ESA | 1989 | Historical; presumed extant | Male & female: fruiting |

~ 50 crowns fruiting | Private |

| 4 | Sweetfern Woods ESA | 1989 | Historical; presumed extant | Male only | ~ 60 crowns | Private |

| 5 | Blytheswood ESA | 2006 | Extant | Unknown: not flowering or fruiting; male & female: fruiting in 1982 |

Dozens of crowns | Private |

| 14 | Point Pelee | 1881 | Extirpated | Extirpated | No info | Extirpated (COSEWIC 2007). Based on a specimen in CAN by Macoun. Never relocated. |

| Norfolk County | ||||||

| 6 | South Walsingham Sand Ridges | 2015 2006 1987 |

Extant | Unknown: not flowering or fruiting at any observation | >100 crowns | Long Point Region Conservation Authority and private owners. |

| Niagara Region | ||||||

| 7 | Drummond Heights | 2013 | Extant | Unknown: not flowering or fruiting; Male & female Fruiting in 2006 |

1 large crowns and 2 smaller crowns | Private |

| 8 | Garner Road A Edgewood Woodlot | 2013 | Extant | Unknown; Female only not fruiting in 2006 |

Patch 15 x >30 m | City of Niagara Falls |

| 9 | Cooks Mills | 1989 | Historical; presumed extant | Unknown: not flowering or fruiting; | >6 crowns | Private |

| 10 | Fenwick | 2006 | Extant | Unknown: not flowering or fruiting; | "Abundant over 0.7 ha" | Private |

| 11 | Lyons Creek North | 2007 | Extant | Male only | Patch 50 x 5 m with hundreds of stems | Private |

| 12 | Woodlawn Park | 2013 | Extant | Unknown: not flowering or fruiting | Patch 60 x 7 m | City of Welland |

| 13 | Garner Road B Fernwood Woodlot | 2013 | Extant | Unknown: info not reported | Patch 36 x 10 m | City of Niagara Falls |

| 15 | Bowman’s Woods West | 2013 | Extant | Unknown: not flowering or fruiting | 2 patches, each with 50-100 stems | City of Niagara Falls |

| 16 | Heartland Forest | 2014 | Extant | Unknown: not flowering or fruiting | ’Rare’ | Private nature centre |

| 17 | McCleod Road | 1980 | Historical; presumed extant | Unknown: info not reported | No info | Private; suitable habitat still present |

Figure 3. Distribution of Round-leaved Greenbrier local populations in Ontario.

3.3 Needs of the Round-leaved Greenbrier

Habitat Needs

In Ontario, Round-leaved Greenbrier is found in moist to wet Carolinian forest, often on sandy soil (Ambrose 1994), in areas just slightly drier than what would be considered swamp, in seasonally but not perpetually flooded ground (Ambrose pers. comm. 2015). The species inhabits both forest understory and forest openings. In Essex County, forests where Round-leaved Greenbrier occurs have been described as Lowland Red Maple-Mixed Oak Forest, or wetter and lower parts of Mixed Oak Forest dominated by Pin Oak (Quercus palustris) and Swamp White Oak (Q. bicolor) (ERCA 1994).

The associated tree and shrub speices reported in Round-leaved Greenbrier habitat are shown in Table 2. In addition, Round-leaved Greenbrier is found associated with many other rare and at-risk Carolinian plants which require specific habitats. Rare associates are shown in Appendix B.

In its greater habitat in the U.S., Round-leaved Greenbrier grows in a variety of dry-moist habitats, including mature Oak Forest and Mixed-Oak Forest, openings in Oak Forest, riparian woods, borders, hedgerows, thickets, old fields and dunes (Brewer et al. 1973; Smith 1974; Voss 1972; Holmes 2002; Abrams and Hayes 2008). It has been described both as an early-successional species which gets established in open conditions and persists as an understory species as forest reclaims the site (Smith 1974), and as a super dominant understory species in a mature (140-year old) mixed-oak coastal plain forest (Abrams and Hayes 2008). Smith (1974) notes that Round-leaved Greenbrier tolerates 70 to 80% shade but matures more rapidly and produces more fruit in forest edge and open situations, and COSEWIC (2007) suggests that forest openings may be required for seedling establishment. However, Carter and Teramura (1998) found that this species can develop the ability to efficiently photosynthesize under low light conditions. Taken together, this suggests that Round-leaved Greenbrier has the potential to be highly adaptable, and grow in a wide-range of successional stages and under a variety of canopy cover conditions.

Although Round-leaved Greenbrier has been reported from dry sites in the U.S. (e.g. Voss 1972; Holmes 2002), it seems to benefit from moist soils in many situations. For example, a study of open habitats in Connecticut found Round-leaved Greenbrier grew significantly faster in moister habitats (Niering and Goodwin 1974). Similarly, Smith (1974) suggests that wetter soils may compensate for slower growth in shaded conditions relative to open conditions. COSEWIC (2007) attributed the slow growth on drier sites to drought stress and to impacts from browsing. Cobb et al. (2007) point out the importance of moisture to recovery from the freeze-thaw cycle experienced during winter. Vines including Smilax spp. have relatively large xylems

Round-leaved Greenbrier appears to tolerate moderate disturbance in its habitat. For example, on lands owned by Long Point Region Conservation Authority (LPRCA), Round-leaved Greenbrier plants are found mainly in areas where canopy openings were created in the late 1980s for a study of different logging treatments (Reader and Bricker 1992; Holmes pers. comm. 2015). In addition, in Michigan, Round-leaved Greenbrier occurs in oak openings (Brewer et al. 1973), which are the result of some type of natural disturbance, usually fire (Kost et al. 2007). Round-leaved Greenbrier may need some disturbance of the ground or litter layer for seedling establishment (Ambrose 1994). The ex`act thresholds of tolerance to disturbance are not known.

Biological Needs

This species is dioecious, with male and female flowers on separate plants. As with all dioecious plants, Round-leaved Greenbrier is an obligate out-crosser, meaning that it must mate with another individual, and self-fertilization does not occur (Kevan et al. 1991). Therefore both male and female plants must be present for sexual reproduction to be possible. Of the seven local populations for which sex has been recorded, three have been observed to contain both male and female plants, three contained only male plants and one only female plants (Table 1), suggesting that sexual reproduction is not likely to be occurring in at least four local Ontario populations.

There are many reasons why both male and female plants may not be present in a single local population. In plants, sex is not necessarily a fixed, genetically-controlled trait. For example, many dioecious species are known to change sex when triggered by certain environmental conditions (such as particular levels of light, temperature, moisture, soil nutrients, etc.) or physical trauma (for example damage from insects or browsing), and some perennial species also change sex as they get older (Freeman et al. 1980). Fragmentation of the landscape, resulting in changes in environmental conditions has been linked to biased sex ratios in another dioecious species, Chinese Pistache (Pistacia chinensis, Yu and Lu 2011). In a related species, Carrion Flower (Smilax herbacea), Sawyer and Anderson (1998) suggested female mortality was the main reason for male-biased sex ratios.

Round-leaved Greenbrier is dependent on pollination by insects, because its pollen is linked together by strands of viscin a natural sticky substance, which prevents the pollen being carried by the wind. The most likely pollinators are mosquitoes, although small flies, small bees and bumble bees may also be important (Kevan et al. 1991). However, in 50 person-hours of observations, only three insects (two mosquitoes and a bumblebee) were observed to land on female Round-leaved Greenbrier flowers, and none were observed on male flowers (Kevan et al. 1991). In addition, even in a mixed-sex local population, artificial pollination increased fruit size and number of seeds compared to flowers allowed to reproduce naturally, suggesting a lack of effective natural pollination (Kevan et al. 1991).

The fruit of Round-leaved Greenbrier is a fleshy berry (5-8 mm in diameter) that is eaten by birds and mammals. The seeds pass through the gut and are dispersed in droppings. As a result, dispersal distances may be large, and seeds may not necessarily fall in locations suitable for growth. Fruit ripen in September to November (Greenberg and Walter 2010). In a study in the southern Appalachian mountains, Round-leaved Greenbrier produced fewer fruit than other native and non-native plants fruiting at the same time, and a significantly lower proportion of fruit were removed over the winter by birds and animals from Round-leaved Greenbrier than from other plants (Greenberg and Walter 2010), suggesting seed dispersal may be limited in this species, relative to other plants producing fruit at the same time of year.

Round-leaved Greenbrier is browsed by wildlife and cattle; of 73 species studied in eastern Texas hardwood forest, greenbriers (Smilax sp.) were among the most heavily grazed (Goodrum 1977). However, this group is very tolerant to browsing, because the rhizomes produce new shoots annually. Goodrum (1977) estimated that 50-60% of annual growth of greenbriers can be eaten without mortality of the roots.

The maximum life span of Round-leaved Greenbrier is not known, but the woody bases of the stems suggest a longer life span than that of smaller, herbaceous greenbrier species. In addition, the rhizomes can persist for years, even after the above-ground part of the plant has been removed (for example by fire or other disturbance; Goodrum 1977). COSEWIC (2007) presumed an age of at least several decades for well-developed individuals.

Relatively little is known about propagation of greenbriers (genus Smilax), including Round-leaved Greenbrier (Luna 2012). Seedling growth in the first year may be quite slow for this species, as plants invest more in growing underground storage organs than in above ground growth (reviewed by Luna 2012). Vegetative propagation using the tubers or rhizomes may be possible (reviewed by Luna 2012), but more research on all aspects of propagation is needed.

Table 2. Associated tree and shrub species reported in Round-leaved Greenbrier habitat in order of frequency (Smith 1974; Ambrose 1994; ERCA 1994).

| English Name | Scientific Name |

|---|---|

| Common associates | |

| Red Maple | Acer rubrum |

| Red Oak | Quercus rubra |

| Pin Oak* | Quercus palustris |

| American Hornbeam | Carpinus caroliniana |

| White Ash* | Fraxinus Americana |

| Sassafras | Sassifras albidum |

| White Oak | Quercus alba |

| American Witch-hazel | Hamamelis virginiana |

| Black Gum* | Nyssa sylvatica |

| Occasional associates | |

| Red Ash* | Fraxinus pennsylvanica |

| Slippery Elm | Ulmus rubra |

| Swamp White Oak | Quercus bicolor |

| Sugar Maple | Acer saccharum |

| Silver Maple | Acer saccharinum |

| American Beech* | Fagus grandifolia |

| Maple-leaved Viburnum | Viburnum acerifolium |

| Eastern Flowering Dogwood* | Cornus florida |

| American Chestnut* | Castanea dentate |

* Species marked with an asterisk are rare or at risk in Ontario, or have declined due to insect infestation, and may no longer be present in the habitat in 2016.

4. Threats

According to COSEWIC (2007) Round-leaved Greenbrier is threatened by habitat loss and modification due to housing development and deer browse. Additional potential threats may be presumed based on threats linked to the biology of Round-leaved Greenbrier, and threats reported for other species at risk (SAR) plants that use Carolinian forest habitats, including high-intensity logging and invasive species. All of these threats may be compounded by natural limitations (discussed at the end of this section), especially existence of single sex local populations and lack of pollinators. Overall, a general stress is the remaining small habitat size in a patchy distribution of isolated woodlots surrounded by agricultural and urban land uses.

4.1 Threat Assessment

Table 3. Threat Assessment Table

| Threat | Level of Concerna | Extent | Occurrence | Frequency | Severityb | Causal Certaintyc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Habitat Loss or Degradation | ||||||

| Residential, industrial and commercial development | High | Widespread | Current | Recurrent | Moderate/High | High |

| High-intensity logging | Medium | Localized | Current | Recurrent | Moderate | Medium |

| Exotic, Invasive, and Introduced Species | ||||||

| Invasive species | Unknown | Widespread | Current | Continuous | Unknown | Low |

| Disturbance or Harm | ||||||

| Inappropriate recreational vehicle use | Low | Localized | Current | Continuous | Low | Low |

| Deer browse | Low | Localized | Historic/Unknown | Recurrent | Low | High |

| Changes in Ecological Dynamics | ||||||

| Alteration of the moisture regime | Medium | Unknown | Current | One-time | Unknown | Medium |

aLevel of Concern: signifies that managing the threat is of (high, medium or low) concern for the recovery of the species, consistent with the population and distribution objectives. This criterion considers the assessment of all the information in the table.

bSeverity: reflects the population-level effect (high: very large population-level effect, moderate, low, unknown).

cCausal certainty: reflects the degree of evidence that is known for the threat (high: available evidence strongly links the threat to stresses on population viability; medium: there is a correlation between the threat and population viability e.g. expert opinion; low: the threat is assumed or plausible).

4.2 Description of Threats

Threats are addressed in order of level of concern.

Residential, industrial and commercial development

Urban development is occurring rapidly in southern Ontario. One site in the Niagara Region was listed by COSEWIC (2007) as being slated for development (local population # 13, recorded as extant in 2013). The woodlots containing local populations # 7 and # 12 have reduced in size due to road construction and residential development (COSEWIC 2007; Sankey pers. comm. 2016). Development pressure continues to be high in that region, and remaining forest patches are commonly used for new residential subdivisions. Twelve of the forest patches that provide habitat for local populations are at least partly privately owned (Table 1), and therefore potentially vulnerable to development. Nevertheless, 11 of the forest patches have some or all of the land in a protective land use designation (section 6.1, Table 1), which may offset the risk of development.

Loss of habitat was a large threat historically when most forest was converted to agricultural use, resulting in the present-day fragmentation and scarcity of Carolinian forest habitat. The remaining Carolinian forest habitat is now very limited. In addition, because Round-leaved Greenbrier requires plants of the opposite sex to reproduce, if only one sex is present, the isolated nature of habitat fragments may be a serious problem. Additional habitat loss may further increase the distances between habitat patches, thus further reducing the likelihood of successful reproduction.

High-intensity Logging

Round-leaved Greenbrier is a long-lived woody species able to tolerate some disturbance in its habitat. At one site, it is associated with openings in the canopy made by moderate forest management activities (Holmes pers. comm. 2015). Therefore, small-scale, selective cutting of trees may not be harmful. However, high-intensity logging may degrade or destroy habitat if it opens the canopy enough to change the moisture regime, and machinery may also directly damage Round-leaved Greenbrier plants. In addition, there could be a cumulative effect from repeated small-scale operations over a number of years. Whether there is active logging in areas with Round-leaved Greenbrier is unknown as the most recent systematic field work was done in 2006, and at that time only about half of the sites were surveyed.

Alteration of the Moisture Regime

Ambrose (1994) lists alteration of drainage patterns though human activities as one of the main threats to Round-leaved Greenbrier at the time of that report. Soil moisture may be particularly important in spring when plants are recovering from the freeze-thaw cycle endured over the winter (Cobb et al. 2007). In addition to development and logging, other human activities both inside and outside forest patches may also change soil moisture levels in Round-leaved Greenbrier habitat. These include ditching ground, changing creek flow, creating berms, or any activity that changes soil or slope around Round-leaved Greenbrier.

Inappropriate Use of Recreational Vehicles

Off-trail use of recreational vehicles (e.g. all-terrain vehicles, ATVs), is a problem on some LPRCA lands and is known to threaten other forest SAR (Holmes pers. comm. 2015). Recreational vehicle use can churn up moist soils, cause ruts, and bring in introduced or invasive non-native species. Any of these results could potentially make habitat unsuitable for Round-leaved Greenbrier.

Deer Browse

Part of one local population (# 4, Table 1) was listed by COSEWIC (2007) as being within a deer enclosure. This local population was subject to excessive pressure from browsing (COSEWIC 2007). While Round-leaved Greenbrier can withstand high levels of browsing (Goodrum 1977), it is likely that this intense browsing pressure from artificially high densities of deer is damaging. It is unknown whether the enclosure is still in place.

Invasive species

Invasive species have not been mentioned as a threat to Round-leaved Greenbrier (Ambrose 1994; COSEWIC 2007), but many invasives are now much more widespread than they were when the COSEWIC report was written. For example, Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata), Glossy Buckthorn (Frangula alnus), and Tartarian Honeysuckle (Lonicera tatarica) are shade-tolerant and able to colonize and take over forest understory areas, and may compete with Round-leaved Greenbrier for space, nutrients or other biological needs (OMNRF 2012). Garlic Mustard in particular may have allelopathic

Other Factors

The Emerald Ash Borer (Agrilus planipennis or EAB) has been documented as a threat to species of Carolinian forests that have a high ash component (Environment Canada 2016). Die-back of ash trees was not mentioned by COSEWIC (2007) as a threat to Round-leaved Greenbrier, but EAB has been spreading rapidly and is present throughout southern Ontario and Quebec (Canadian Food Inspection Agency 2015). The loss of ash and opening of the canopy are likely to have strong impacts on many Carolinian species, but the direct implications to Round-leaved Greenbrier are unknown, and oaks and maples are more important canopy associates for Round-leaved Greenbrier than ash. The opening of the canopy through loss of ash could negatively impact Round-leaved Greenbrier, if loss is extensive enough to impact soil moisture regime, or may even have positive effects through increase in light levels.

4.3 Natural Limitations

Of seven local populations for which information on plant sex are available, four contained only single sex plants (three contained only male plants and one only female), meaning these local populations can only reproduce vegetatively, not sexually. This leads to reduced genetic variability in both local and total populations, which may be detrimental to the long-term survival of the species in Canada. It is unknown why these local populations contain only one sex, or whether environmental conditions are limiting the expression of either male or female plants in these local populations.

Round-leaved Greenbrier may suffer from limited pollinators. In 50 person-hours of observations, only three insects (two mosquitoes and a bumblebee) were observed to land on female Round-leaved Greenbrier flowers, and none were observed on male flowers (Kevan et al. 1991). In addition, when hand-pollinated flowers were compared with flowers left to be pollinated naturally, fruit size was smaller and there were fewer seeds in the flowers left alone, showing a lack of effective natural pollination (Kevan et al. 1991). It is not clear why there may be a lack of pollinators, or if a particular insect group may be missing from Round-leaved Greenbrier habitat. However, loss of Carolinian forest cover in Ontario has been shown to cause a reduction of bee species richness and abundance, and to correlate to reduced seed set in at least two self‑incompatible plant species (Taki et al. 2007; 2008). In addition, in Canada and globally many insect populations are declining (especially bees) due to loss of habitat and food sources, diseases, pests, and pesticide exposure (Health Canada 2015). It is currently unknown what impact the decline in pollinator populations may have on Round-leaved Greenbrier.

5. Population and Distribution Objectives

The population and distribution objectives for Round-leaved Greenbrier, Great Lakes Plains population, are:

- Maintain the species’ distribution (including any new local populations that are discovered);

- Maintain or, where necessary and technically and biologically feasible, increase abundance at the 16 extant and presumed extant local populations.

Round-leaved Greenbrier is a robust and long-lived plant, with a range of habitat tolerances within moist forest. There is no evidence for recent extirpation of local populations, where forested habitat remains (see section 3.2) and best available information indicates that forested habitat remains at the location of each of the historical local populations. Therefore, the six local historical populations are presumed extant for the purposes of this recovery strategy.

Due to uncertainty about the abundance of individual plants (COSEWIC 2007) and lack of recent information about a number of local populations (Table 1), setting quantitative abundance objectives is not possible at this time. There is no indication that Round-leaved Greenbrier was ever more widespread in Ontario than its current distribution. Therefore, the recovery objectives aim to maintain the existing distribution and abundance of local populations. If any new local populations are discovered (for example, three additional local populations have been discovered since the 2007 COSEWIC assessment), these should also be maintained.

Even if the distribution and abundance of Round-leaved Greenbrier is maintained, the long-term resilience of the species is not ensured as several local populations have low abundance (e.g. # 7, Drummond Heights, # 9 Cooks Mills; Table 1) and it is possible that the majority of the population is currently reproducing vegetatively. This is supported by the existence of single-sex local populations (four of seven local populations where sex-ratio is known), and by the lack of observations of seedlings in any recent surveys. In the absence of sexual reproduction, genetic diversity is likely to decline, increasing the risk of inbreeding and reducing the ability of the species to recover from perturbations. Establishing sexually reproducing local populations by augmenting existing single-sex local populations with individuals of the opposite sex, if biologically or technically feasible, and researching factors that promote seedling production and survival may both help to increase abundance at existing local populations.

6. Broad Strategies and General Approaches to Meet Objectives

6. 1. Actions Already Completed or Currently Underway

Eleven local populations have some or all of the land in a conservation land use designation. On lands owned by Long Point Region Conservation Authority, Round-leaved Greenbrier is located in some areas that are working forest with active logging operations. These areas are surveyed prior to work commencing, and a buffer is established around the species to protect it (Holmes pers. comm. 2015).

6.2. Strategic Direction for Recovery

Table 4. Recovery Planning Table

| Threat or Limitation | Prioritya | Broad Strategy to Recovery | General Description of Research and Management Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge gaps | High | Surveys and monitoring |

|

| Low rate of seedling establishment; single-sex local populations | High | Research and management |

|

| Development; Alteration of the moisture regime |

High | Land use policy and planning; |

|

| Development | High | Habitat protection; Partnerships |

|

| Development, high‑intensity logging, alteration of the moisture regime | High | Outreach and education |

|

| Knowledge gaps | High | Research on natural limitations |

|

| Inappropriate \use of recreational vehicles | Low | Outreach and education |

|

| Invasive species, deer browse, EAB | Low | Monitoring; Habitat management |

|

aPriority” reflects the degree to which the broad strategy contributes directly to the recovery of the species or is an essential precursor to an approach that contributes to the recovery of the species.

7. Critical Habitat

7.1. Identification of the Species’ Critical Habitat

Section 41(1)(c) of SARA requires that recovery strategies include an identification of the species’ critical habitat, to the extent possible, as well as examples of activities that are likely to result in its destruction. Under section 2(1) of SARA, critical habitat is “the habitat that is necessary for the survival or recovery of a listed wildlife species and that is identified as the species’ critical habitat in the recovery strategy or in an action plan for the species”.

This federal recovery strategy identifies critical habitat for Round-leaved Greenbrier (Great Lakes Plains population) in Canada to the extent possible, based on the best available information as of February 2016. Critical habitat is identified for all existing local populations

Critical habitat identification for Round-leaved Greenbrier (Great Lakes Plains population) is based on two criteria: habitat occupancy and habitat suitability.

7.2. Habitat Occupancy

The habitat occupancy criterion refers to areas of suitable habitat where there is a reasonable degree of certainty of current use by the species.

Habitat is considered occupied when:

- At least one Round-leaved Greenbrier stem has been observed, and

- The location has not been classified as extirpated

footnote 26 .

Habitat occupancy is based on occurrence reports available for all local populations from the NHIC and COSEWIC, as well as other project based data reports (Garofalo pers. comm. 2016; Parks pers. comm. 2016; Sankey pers. comm. 2016). Within Ontario, Round-leaved Greenbrier is reported from ten extant and six historical local populations. Due to the robustness and longevity of Round-leaved Greenbrier (up to at least several decades, and perhaps even centuries; COSEWIC 2007), historical local populations with existing suitable habitat where the species has not been recently surveyed are presumed to be extant and considered occupied. If new observations become available for additional local populations, they may be considered for the identification of additional critical habitat in future action plans or recovery strategies.

Habitat occupancy is therefore presumed as extant for all non-extirpated local populations listed in Table 1 as of February 2016.

7.3. Habitat Suitability

Habitat suitability relates to areas possessing a specific set of biophysical attributes that can support individuals of the species in carrying out essential aspects of their life cycle. At existing local populations in Ontario, Round-leaved Greenbrier is typically found growing in Carolinian forests with a variety of habitat types dominated by Red Maple (Acer rubrum) and Pin Oak (Quercus palustris), in combination with several other overstorey species including but not limited to Red Oak (Quercus rubra), American Hornbeam (Carpinus caroliniana), White Ash (Fraxinus americana), Sassafras (Sassafras albidum), White Oak (Quercus alba), American Witch-hazel (Hamamelis virginiana), or Black Gum (Nyssa sylvatica) (ERCA 1994; COSEWIC 2007).

The biophysical attributes, which capture the characteristics required by the species to carry out its life processes, include:

- Moist to wet wooded habitat often with sandy soils

- Slightly drier than what would be considered swamp, typically in seasonally but not perpetually flooded grounds (Ambrose pers. comm. 2015)

Based on the best available information, suitable habitat for Round-leaved Greenbrier is currently defined as the extent of the biophysical attributes where Round-leaved Greenbrier exists in Ontario. Further detail is provided below.

Due to the range of forested habitat that Round-leaved Greenbrier can occupy, suitable habitat for Round-leaved Greenbrier in Ontario is best captured using the OMNRF (2014) wooded area boundary. This framework provides an approach to the interpretation and delineation of woody vegetation boundaries according to Ontario Base Mapping standards to identify wooded areas in Southern Ontario

The entire contiguous forest patch around the plant, as defined by the wooded area boundary, is considered critical habitat. This allows for growth of existing plants and an increase in abundance of plants, as outlined in the population and distribution objectives, and acts to maintain the microhabitat conditions for the plant, along with the functional integrity of the forest. Maintaining the functional integrity of the forest will help to maintain the soil moisture regime essential to this species, as well as promoting the abundance of insect pollinators for Round-leaved Greenbrier (COSEWIC 2007; Taki et al. 2007), as limited pollinators may be a factor in lack of sexual reproduction (Kevan et al. 1991).

Human-made structures (e.g., maintained roadways, buildings) do not possess the biophysical attributes of suitable habitat or assist in the maintenance of natural processes and are therefore not identified as critical habitat.

7.4. Application of Criteria to Identify Critical Habitat for Round-leaved Greenbrier

Critical habitat for Round-leaved Greenbrier is identified as the extent of suitable habitat (section 7.1.2) where the habitat occupancy criteria is met (section 7.1.1).

In Ontario, as noted above, suitable habitat for Round-leaved Greenbrier is most appropriately identified with wooded area boundaries. Critical habitat is located within these boundaries where the biophysical attributes described in section 7.1.2 are found and where the occupancy criterion is met (section 7.1.1).

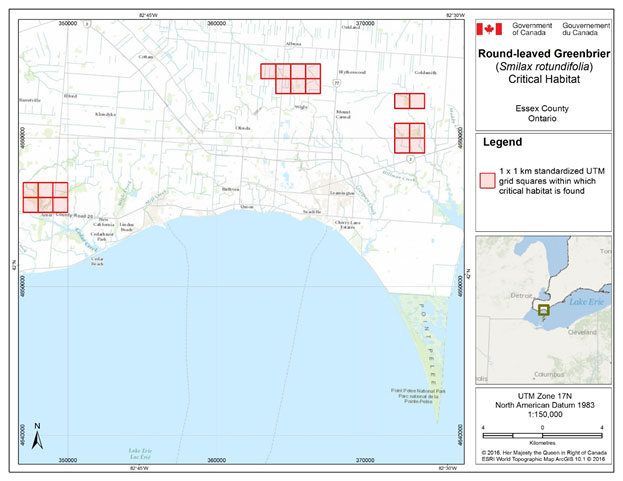

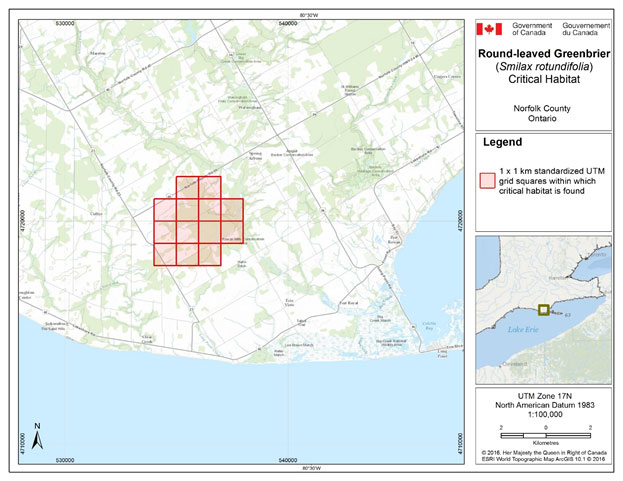

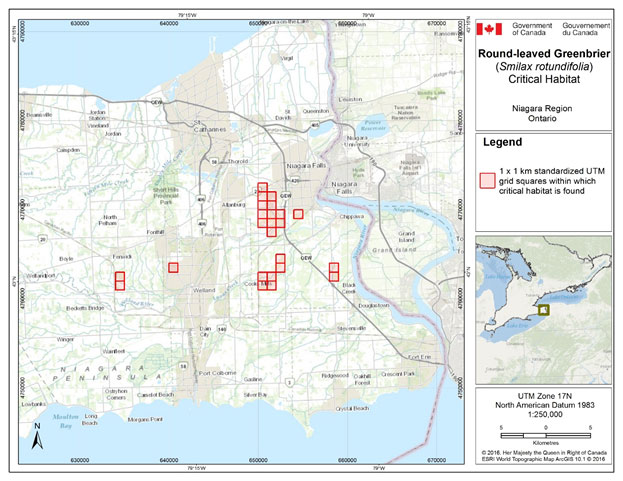

Application of the critical habitat criteria above to the best available information identifies critical habitat for 16 local populations of Round-leaved Greenbrier, Great Lakes Plains population in Canada (see Figures 4, 5, and 6; Table 5). The critical habitat identified is considered a full identification of critical habitat and is sufficient to meet the population and distribution objectives for Round-leaved Greenbrier.

Critical habitat identified for Round-leaved Greenbrier is presented using 1 x 1 km UTM grid squares. The UTM grid squares presented in Figure 4, Figure 5, and Figure 6 are part of a standardized grid system that indicates the general geographic areas containing critical habitat, which can be used for land use planning and/or environmental assessment purposes. In addition to providing these benefits, the 1 x 1 km UTM grid respects data-sharing agreements with the province of Ontario. Critical habitat within each grid square occurs where the description of habitat occupancy (section 7.1.1) and habitat suitability (section 7.1.2) are met. More detailed information on critical habitat to support protection of the species and its habitat may be requested on a need-to-know basis by contacting Environment and Climate Change Canada – Canadian Wildlife Service at ec.planificationduretablissement-recoveryplanning.ec@canada.ca.