SIU Director’s Report - Case # 17-OVI-062

Issued: April 6, 2018

Mandate of the SIU

The Special Investigations Unit is a civilian law enforcement agency that investigates incidents involving police officers where there has been death, serious injury or allegations of sexual assault. The Unit’s jurisdiction covers more than 50 municipal, regional and provincial police services across Ontario.

Under the Police Services Act, the Director of the SIU must determine based on the evidence gathered in an investigation whether an officer has committed a criminal offence in connection with the incident under investigation. If, after an investigation, there are reasonable grounds to believe that an offence was committed, the Director has the authority to lay a criminal charge against the officer. Alternatively, in all cases where no reasonable grounds exist, the Director does not lay criminal charges but files a report with the Attorney General communicating the results of an investigation.

Information restrictions

Freedom of Information and Protection of Personal Privacy Act (“FIPPA”)

Pursuant to section 14 of FIPPA (i.e., law enforcement), certain information may not be included in this report. This information may include, but is not limited to, the following:

- Confidential investigative techniques and procedures used by law enforcement agencies; and

- Information whose release could reasonably be expected to interfere with a law enforcement matter or an investigation undertaken with a view to a law enforcement proceeding.

Pursuant to section 21 of FIPPA (i.e., personal privacy), protected personal information is not included in this document. This information may include, but is not limited to, the following:

- subject officer name(s)

- witness officer name(s)

- civilian witness name(s)

- location information

- witness statements and evidence gathered in the course of the investigation provided to the SIU in confidence and

- other identifiers which are likely to reveal personal information about individuals involved in the investigation

Personal Health Information Protection Act, 2004 (“PHIPA”)

Pursuant to PHIPA, any information related to the personal health of identifiable individuals is not included.

Other proceedings, processes, and investigations

Information may have also been excluded from this report because its release could undermine the integrity of other proceedings involving the same incident, such as criminal proceedings, coroner’s inquests, other public proceedings and/or other law enforcement investigations.

Mandate engaged

The Unit’s investigative jurisdiction is limited to those incidents where there is a serious injury (including sexual assault allegations) or death in cases involving the police.

“Serious injuries” shall include those that are likely to interfere with the health or comfort of the victim and are more than merely transient or trifling in nature and will include serious injury resulting from sexual assault. “Serious Injury” shall initially be presumed when the victim is admitted to hospital, suffers a fracture to a limb, rib or vertebrae or to the skull, suffers burns to a major portion of the body or loses any portion of the body or suffers loss of vision or hearing, or alleges sexual assault. Where a prolonged delay is likely before the seriousness of the injury can be assessed, the Unit should be notified so that it can monitor the situation and decide on the extent of its involvement.

This report relates to the SIU’s investigation into the serious injury reportedly sustained by a 27-year-old man during a police pursuit.

The investigation

Notification of the SIU

At approximately 10:10 p.m. on Saturday, April 1st, 2017, the Hanover Police Service (HPS) notified the SIU of the Complainant’s vehicle injury. The HPS reported that on Saturday, April 1st, 2017, at approximately 9:20 p.m., the HPS received a call regarding a four-wheel-drive ‘All-Terrain Vehicle’ (ATV) driving through town with no lights on.

The Subject Officer (SO) observed the ATV, activated his police vehicle’s emergency equipment, and pursued the ATV southbound on 6th Street [now known to be 6th Avenue]. The ATV collided with a vehicle at 10th Street, and a third vehicle was also struck. The man operating the ATV, the Complainant, was ejected from the ATV. The Complainant was taken to the hospital and then transferred by air-ambulance to a second hospital.

The team

Number of SIU Investigators assigned: 7

Number of SIU Forensic Investigators assigned: 2

Upon request, the SIU obtained the electronic data created by the westbound Chrysler’s Crash Data Retrieval (CDR) system when it was struck by the ATV operated by the Complainant from the Ontario Provincial Police (OPP) Technical Traffic Collision Investigator (TTCI).

SIU investigators interviewed civilian and police witnesses, conducted a canvass for additional witnesses, and searched for closed circuit television (CCTV) images relevant to the incident.

Efforts were made to interview the Complainant, however, due to the nature and extent of his brain injury, the Complainant was unable to provide any information to advance the investigation of the incident. At the time of writing of this report, the Complainant remains admitted to hospital in stable condition recovering from his traumatic brain injury. Since his treatment is continuing, current medical records for the Complainant relevant to the incident were not available.

SIU Forensic Investigator (FI) made a digital photographic record and drawing of the scene, collected physical evidence, and seized exhibits relevant to the incident. The FI also made daylight and nocturnal video recordings of the route taken by the Complainant and the SO during the incident.

Complainant

27-year-old male, unable to be interviewed due to the severe nature of his injuries; some medical records obtained and reviewed

Civilian witnesses

CW #1 Interviewed

CW #2 Interviewed

CW #3 Interviewed

CW #4 Interviewed

CW #5 Interviewed

CW #6 Not interviewed

CW #7 Interviewed

CW #8 Interviewed

CW #9 Not interviewed

CW #10 Not interviewed

CW #11 Interviewed

CW #12 Interviewed

CW #13 Interviewed

CW #14 Interviewed

CW #15 Interviewed

CW #16 Interviewed

CW #17 Interviewed

CW #18 Interviewed

CW #19 Interviewed

CW #20 Interviewed

CW #21 Interviewed

CW #22 Interviewed

CW #23 Interviewed

CW #24 Interviewed

CW #s 6, 9 and 10 were not interviewed as they did not have any information to advance the investigation that was not already known from other civilian and police witnesses that were interviewed, and from electronic data obtained during the investigation.

Witness officers

WO #1 Interviewed, notes received and reviewed

WO #2 Interviewed, notes received and reviewed

WO #3 Interviewed, notes received and reviewed

WO #4 Interviewed, notes received and reviewed

Subject officers

SO #1 Declined interview and to provide notes, as is the subject officer’s legal right

Incident narrative

On April 1st, 2017, a number of callers contacted the HPS to report that an ATV being driven on the streets in the Town of Hanover after dark, without any headlights. As a result, the HPS dispatcher notified officers in the area that the ATV was in breach of the Town of Hanover by-laws which prohibited the operation of ATV

At approximately 9:20 p.m., a stationary fully marked HPS police cruiser operated by the SO was observed facing south on 8th Avenue, north of its intersection with 13th Street. The ATV operated by the Complainant was observed in the same area, without functional head and/or tail-lights, traveling westbound on 13th Street at a high rate of speed.

The SO entered his police cruiser and immediately drove south and west, following the ATV. The police cruiser’s emergency lights were not operating at that time. Both vehicles continued onto 13th Street travelling westbound at a rate of speed above the posted speed limit of 50 km/h.

The ATV operated by the Complainant and the SO’s police cruiser continued west to 7th Avenue, then north a short distance where they went west on the continuation of 13th Street, then south onto 6th Avenue to its intersection with 10th Street, where the ATV failed to stop for a stop sign and collided with the right side of a westbound Chrysler motor vehicle.

The collision caused the Complainant to be ejected from the ATV, travel through the air for a distance of about 30 feet losing his helmet and then land head-first on the pavement in the intersection.

As a result of the Complainant’s head impacting with the pavement, the Complainant sustained a significant laceration and, more significantly, a severely fractured skull and near-fatal brain injuries.

Nature of injuries / treatment

The Complainant sustained a serious brain injury and multiple ‘eggshell’ fractures of his skull. He was treated on an emergency basis with a craniectomy, in which a substantial portion of his skull was surgically removed to permit his brain to swell sufficiently and to prevent it from swelling within the cranium and compressing his brain stem.

The Complainant remained in critical care for approximately two weeks and was discharged to an infirmary associated with a custodial facility where he was to wear a protective helmet at all times. During his admission in the infirmary, the Complainant suffered an unprotected fall and struck his head on the site of the craniectomy. At the time of this report, the Complainant remains in a brain injury facility at a hospital and may remain there indefinitely.

Evidence

The scene

Route survey

The route taken by the Complainant and the SO was surveyed by the SIU on April 18th, 2017, between 5:47 p.m. and 9:11 p.m. The survey included video recordings made at 7:14 p.m., and 9:11 p.m., and both surveys commenced at an address on 10th Street and followed along 10th Street northbound to 13th Street, then westbound along 13th Street to a T-intersection at 7th Avenue. The surveyed route continued northbound on 7th Avenue to an immediate left turn onto the continuation of 13th Street. At 6th Avenue the route turned south and followed this road to the intersection of 10th Street where the collision occurred.

The roads in this area were in essentially a residential neighbourhood and were asphalt- paved and dry. There were numerous mature trees and street lights along the roadways. The stop signs controlling the route taken by the Complainant and the SO at the intersections referred to herein were properly erected and visible. Several No Parking signs were noted along the route. The total distance of the route was recorded as 600 metres.

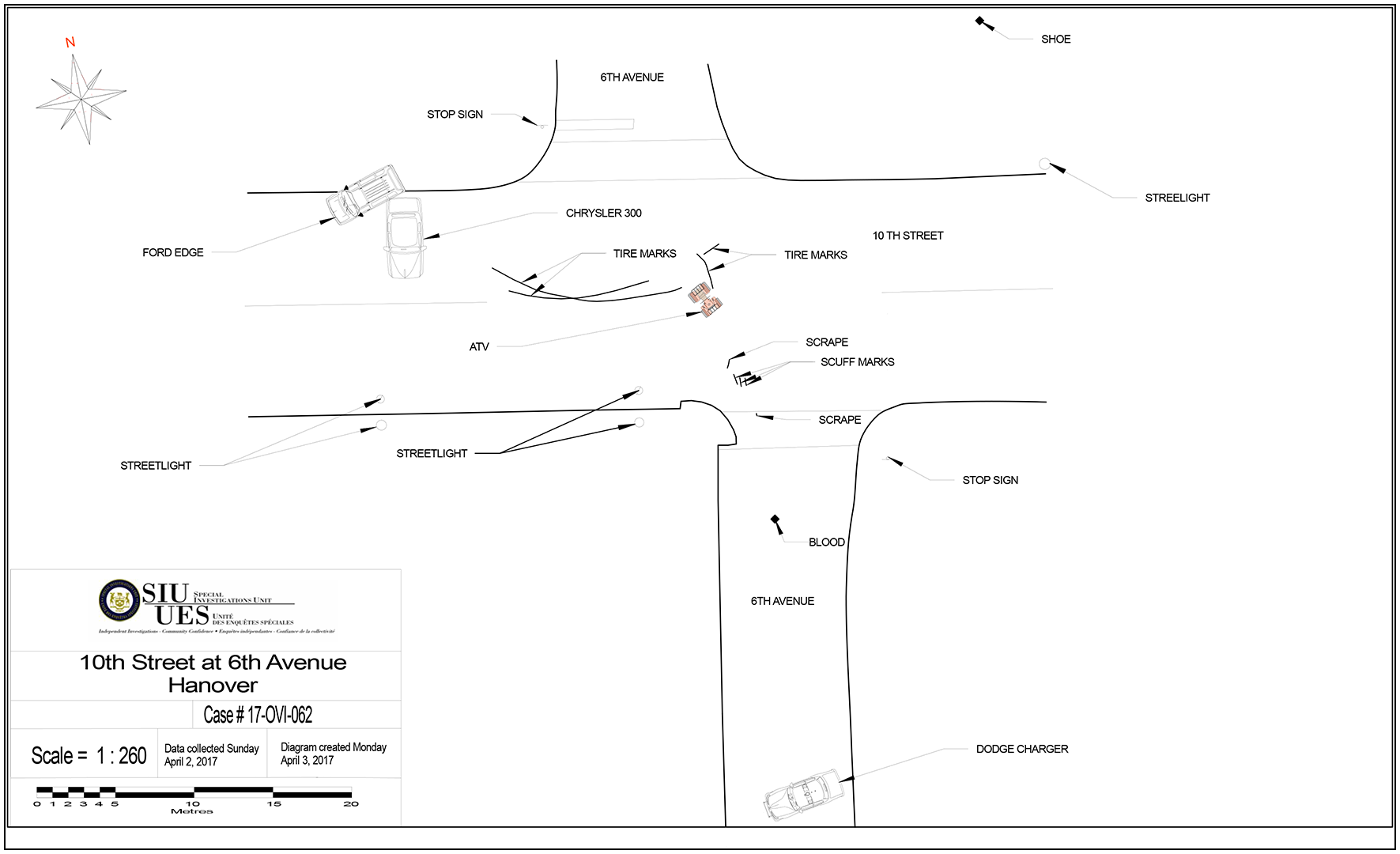

Scene diagram

Physical evidence

The ATV operated by the Complainant, and the Complainant’s clothing and footwear worn at the time of the incident, were examined. No evidence of intra-vehicular contact involving the ATV and/or the Complainant and the police vehicle operated by the SO was found.

HPS GPS/Automatic Vehicle Locator (AVL) data

In spite of the lack of synchronicity of the time stamps associated with the communications audio recordings and the GPS/AVL data created by the SO’s police vehicle, the SO was stationary on 8th Avenue at 9:21:57 p.m., and stationary at the scene of the collision, approximately one minute later at 9:22:57 p.m. Three seconds later, at approximately 9:23:00 p.m., when the SO had access to the police radio transmission band, he was summoning immediate emergency medical services as described above.

The GPS/AVL data was recorded at 15-second intervals and depicted the SO’s vehicle stationary at 9:21:57 p.m., on 8th Avenue, having a north/south bearing, near its intersection with 13th Street having an east/west bearing.

Fifteen seconds later at 9:22:12 p.m., the SO’s vehicle was depicted westbound on 13th Street having an east/west bearing, marginally east of its intersection with 7th Avenue, at 61.16 km/h.

Fifteen seconds later at 9:22:27 p.m., the SO’s vehicle was depicted southbound on 6th Avenue, marginally south of 13th Street, at 41.84 km/h.

Fifteen seconds later at 9:22:42 p.m., the SO’s vehicle was depicted still southbound marginally north of its intersection with 10th Street [now known to be the collision scene] also having an east west/bearing, at 28.97 km/h.

Fifteen seconds later at 9:22:57 p.m., the SO’s vehicle was depicted stationary at the collision scene.

In summary, the HPS Communications Audio Recordings and GPS/AVL data were consistent with, but independent of, the civilian witnesses who provided information regarding the location and duration of the SO’s police vehicle’s movements during the short-lived suspect apprehension pursuit that did not exceed 60 seconds.

Collision Data Recovery (CDR) from Chrysler motor vehicle

The CDR data indicated that the airbags deployed at about the same moment the vehicle was struck by the ATV, and that the brake lights of the Chrysler illuminated at about the same time the airbags deployed.

Forensic evidence

No submissions were made to the Centre of Forensic Sciences.

Video/audio/photographic evidence

CCTV data - Residence located on 5th Avenue, Hanover

The data recorded on April 1st, 2017, at about 8:58 p.m., depicted an ATV without any headlights travelling southeast across the front lawn of the residence and, moments later after it had left the focal range of the camera, was depicted travelling northwest across the same front lawn and leaving the camera’s focal range.

CCTV data – Commercial Premises on 10th Street, Hanover

The data recorded April 1st, 2017, at about 9:23 p.m., depicted the brake lights of the westbound Chrysler illuminating at the time it was struck by the southbound ATV and the SO’s cruiser with its emergency lights flashing as it arrived at the scene from north of the collision.

Communications recordings

HPS communications audio recordings

On April 1st, 2017, at approximately 0:20:07 p.m., the 911 call placed by CW #12 commenced. The call terminated one minute and 57 seconds later at 9:22:00 p.m.

Approximately 28 seconds later, at 9:22:28 p.m., the police dispatcher advised the SO and WO #1 of CW #12’s information. The police dispatcher’s radio transmission had a duration of approximately 37 seconds, terminating at 9:23:05 p.m.

At approximately 9:23:00 pm, the SO was already at the collision scene on the police radio requesting the immediate attendance of emergency medical services.

Accordingly, the approximate amount of time that elapsed from CW #12’s 911 call that commenced at 9:20:07 p.m., until the Complainant’s collision with the westbound Chrysler sedan, which included the SO’s pursuit of the ATV operated by the Complainant, was two minutes and 53 seconds. Within that timeframe, the Complainant drove north from the location on 10th Avenue, where he was observed but not identified by CW #12, and then west past the SO’s location where the SO was concluding an unrelated call for service, and caught the SO’s attention.

Materials obtained from Police Service

Upon request, the SIU obtained and reviewed the following materials and documents from the HPS

- Communications audio recordings including 911 calls made relevant to the incident

- Event Details Report

- Facebook ® Screenshot received from WO #3-2017-04-02

- Global Positioning System (GPS) data pertaining to the HPS vehicles operated by the SO and WO #1

- HPS Canadian Police Information Centre (CPIC) report regarding stolen ATV

- HPS General Order: Suspect Apprehension Vehicle Pursuits

- HPS Scene Photographs

- Notes of WO #s 1-4, and

- Training Record for the SO

Upon request, the SIU obtained the following additional materials from other sources:

- Ambulance Call Report - Grey County Emergency Medical Service (EMS)

- CCTV data from a residence located on 5th Avenue, Hanover

- CCTV data from a commercial premises on 10th Street, Hanover

- Incident Report – Grey County EMS, and

- The Complainant’s medical records relevant to the incident

Relevant legislation

Sections 1-3, Ontario Regulation 266/10, Ontario Police Services Act – Suspect Apprehension Pursuits

1. (1) For the purposes of this Regulation, a suspect apprehension pursuit occurs when a police officer attempts to direct the driver of a motor vehicle to stop, the driver refuses to obey the officer and the officer pursues in a motor vehicle for the purpose of stopping the fleeing motor vehicle or identifying the fleeing motor vehicle or an individual in the fleeing motor vehicle.

(2) A suspect apprehension pursuit is discontinued when police officers are no longer pursuing a fleeing motor vehicle for the purpose of stopping the fleeing motor vehicle or identifying the fleeing motor vehicle or an individual in the fleeing motor vehicle.

2. (1) A police officer may pursue, or continue to pursue, a fleeing motor vehicle that fails to stop,

- if the police officer has reason to believe that a criminal offence has been committed or is about to be committed; or

- for the purposes of motor vehicle identification or the identification of an individual in the vehicle.

(2) Before initiating a suspect apprehension pursuit, a police officer shall determine that there are no alternatives available as set out in the written procedures of,

- the police force of the officer established under subsection 6 (1), if the officer is a member of an Ontario police force as defined in the Interprovincial Policing Act, 2009;

- a police force whose local commander was notified of the appointment of the officer under subsection 6 (1) of the Interprovincial Policing Act, 2009, if the officer was appointed under Part II of that Act; or

- the local police force of the local commander who appointed the officer under subsection 15 (1) of the Interprovincial Policing Act, 2009, if the officer was appointed under Part III of that Act.

(3) A police officer shall, before initiating a suspect apprehension pursuit, determine whether in order to protect public safety the immediate need to apprehend an individual in the fleeing motor vehicle or the need to identify the fleeing motor vehicle or an individual in the fleeing motor vehicle outweighs the risk to public safety that may result from the pursuit.

(4) During a suspect apprehension pursuit, a police officer shall continually reassess the determination made under subsection (3) and shall discontinue the pursuit when the risk to public safety that may result from the pursuit outweighs the risk to public safety that may result if an individual in the fleeing motor vehicle is not immediately apprehended or if the fleeing motor vehicle or an individual in the fleeing motor vehicle is not identified.

(5) No police officer shall initiate a suspect apprehension pursuit for a non-criminal offence if the identity of an individual in the fleeing motor vehicle is known.

(6) A police officer engaging in a suspect apprehension pursuit for a non-criminal offence shall discontinue the pursuit once the fleeing motor vehicle or an individual in the fleeing motor vehicle is identified.

3. (1) A police officer shall notify a dispatcher when the officer initiates a suspect apprehension pursuit.

(2) The dispatcher shall notify a communications supervisor or road supervisor, if a supervisor is available, that a suspect apprehension pursuit has been initiated

Section 249, Criminal Code - Dangerous operation of motor vehicles, vessels and aircraft

249 (1) Every one commits an offence who operates

- a motor vehicle in a manner that is dangerous to the public, having regard to all the circumstances, including the nature, condition and use of the place at which the motor vehicle is being operated and the amount of traffic that at the time is or might reasonably be expected to be at that place…

- Every one who commits an offence under subsection (1) and thereby causes bodily harm to any other person is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding ten years.

Section 62 (1), Highway Traffic Act – Lamps required on all motor vehicles except motorcycles

62 (1) When on a highway at any time from one-half hour before sunset to one-half hour after sunrise and at any other time when, due to insufficient light or unfavourable atmospheric conditions, persons and vehicles on the highway are not clearly discernible at a distance of 150 metres or less, every motor vehicle other than a motorcycle shall carry three lighted lamps in a conspicuous position, one on each side of the front of the vehicle which shall display a white or amber light only, and one on the rear of the vehicle which shall display a red light only.

Section 1(1), Highway Traffic Act – Definition: Highway

1(1) “highway” includes a common and public highway, street, avenue, parkway, driveway, square, place, bridge, viaduct or trestle, any part of which is intended for or used by the general public for the passage of vehicles and includes the area between the lateral property lines thereof.

Section 216 (1) Highway Traffic Act of Ontario – Power of Police Officer to Stop Vehicles

216 (1) A police officer, in the lawful execution of his or her duties and responsibilities, may require the driver of a vehicle, other than a bicycle, to stop and the driver of a vehicle, when signaled or requested to stop by a police officer who is readily identifiable as such, shall immediately come to a safe stop.

216 (2) Every person who contravenes subsection (1) is guilty of an offence and on conviction is liable, subject to subsection (3),

- to a fine of not less than $1, 000 and not more than $10, 000;

- to imprisonment for a term of not more than six months; or

- to both a find and imprisonment.

Analysis and Director’s decision

On April 1st, 2017, the Complainant was operating an all-terrain vehicle (ATV) in the Town of Hanover at approximately 9:20 p.m. when he came to the attention of the Subject Officer (SO), who tried to bring the ATV to a stop. The Complainant was operating the ATV on town streets, which is against the Town of Hanover by-laws, and he did not have his lighting system activated, contrary to s.62 of the Highway Traffic Act (HTA).

According to eight civilian witnesses (CWs) located at various locations along the route taken by the SO and the Complainant, the SO, in his marked police cruiser, pursued the Complainant, on his ATV, from his first sighting in the approximate area of 8th Avenue and 13th Street, westbound on 13th Street, northbound on 7th Avenue, westbound again on 13th Street, and southbound on 6th Avenue to the intersection with 10th Street, where the Complainant ultimately crashed his ATV into a motor vehicle operated by CW #5, who was driving westbound on 10th Street at the time.

The Complainant was ejected from the ATV, his helmet was dislodged, and he landed, head first, striking his bare head onto the pavement; his helmet was found on the roadway nearby. The Complainant was transported first to the Hanover Hospital, then air-lifted to the London Hospital, and then to a Toronto hospital, where he was treated for a significantly fractured skull and near-fatal brain injuries. The Complainant is still in hospital for ongoing treatment for his traumatic brain injury at the time of this report, and could not be interviewed; it is not likely that he will recover.

During the course of this investigation, 21 civilian and four police witnesses were interviewed. The SO declined to be interviewed or to provide his memorandum book notes for review, as was his legal right. Investigators also had access to the notes of the four police witnesses, the 911 and police communications recordings and log, the GPS data from the involved police vehicles, the Crash Data Retrieval (CDR) System from the motor vehicle operated by CW #5, closed circuit television (CCTV) data from nearby commercial premises along the route covered by the Complainant and the SO, physical exhibits and photos from the scene, and some of the Complainant’s medical records. As a result of the absence of any input from the two directly involved parties, the Complainant and the SO, SIU Investigators had to piece together the sequence of events extrapolated from the available material evidence.

Three CWs observed a male person, presumably the Complainant, operating an ATV between 6:00 and 9:14 p.m. and each person observed him to be driving on the streets of Hanover without the necessary lighting equipment activated on the ATV. The third witness contacted the Hanover Police Service (HPS) and asked them to send an officer to deal with the driver, as he was in breach of Hanover by-laws.

As a result of that call, a radio transmission went out to HPS officers at 9:22:28 p.m. stating that a person was driving a four wheeler on the street with no headlights. Since the recording does not reveal that the SO ever responded to that call, it is unclear whether his subsequent actions were as a result of the call out from the dispatcher, or if he just coincidentally observed the ATV as he was exiting a residence on 8th Street, which was not where the dispatcher had directed police vehicles to look for the ATV in any event.

The first civilian witness, CW #20, who observed both the Complainant and the SO, did so in the area of 8th Avenue and 13th Street, where she first observed the Complainant driving the ATV, and then the SO entering his marked police cruiser and following him westbound on 13th Street in excess of the 50 km/h speed limit. The SO did not have his emergency lighting equipment activated at that time.

According to the GPS/AVL data from the SO’s police cruiser, it was stationary on 8th Avenue at 9:21:57 p.m. This is consistent with the evidence of CW #20, who observed the SO just prior to his entering his cruiser and leaving the area. Unfortunately the GPS/AVL data only recorded the speed of the SO’s vehicle every 15 seconds, and as such it is difficult to determine the speed of the SO’s vehicle at all times. The second recording of the speed of the SO’s vehicle was at 9:22:12 p.m., while he was travelling on 13th Street east of its intersection with 7th Avenue, at which time he was travelling at 61.16 km/h.

The next two witnesses, CW #1 and CW #13, observed the ATV and the SO in his police cruiser in the area of 13th Street and 6th Avenue. Both observed the SO to have his emergency lighting equipment activated, but no siren. While CW #13 only heard, but did not see, the ATV, she described the police vehicle as chasing the ATV and estimated that the cruiser was the length of approximately one to two houses behind the ATV; she described the cruiser speed as not overly fast.

CW #1 described the ATV as moving at approximately 40 km/h with the police cruiser about 15 feet behind him. She observed both vehicles turn south onto 6th Avenue in a controlled fashion, at which point the ATV accelerated to an estimated speed of 80 to 90 km/h and the cruiser also accelerated. CW #1 observed the brake lights on the ATV to illuminate once or twice as it approached the stop sign at 10th Street and she was of the view that the police cruiser was chasing the ATV and was too close, possibly within a few feet, and she was surprised that the cruiser did not collide with the ATV. CW #1 described the police cruiser as having chased the ATV “intensely” through town.

The GPS/AVL data of the SO’s cruiser indicated that he was travelling at 41.84 km/h at 9:22:27 p.m., while travelling southbound on 6th Avenue, just marginally south of 13th Street. This reading is consistent with the evidence of CW #1, that both the SO and the Complainant made a controlled turn from 13th Street onto 6th Avenue and were moving at approximately 40 km/h, after which they both sharply accelerated.

On 6th Avenue, five civilian witnesses observed the SO and the ATV.

The first, CW #11, who was closer to 13th Street, observed an ATV travelling south on 6th Avenue at high speeds, with no headlights, while a police cruiser, with its emergency lighting activated but no siren, followed at high speeds. CW #11 thought that the cruiser was going to hit him (CW #1), so he jumped to the west side of the road.

CW #24 observed an ATV go “flying by” the intersection of 12th Street on 6th Avenue, with an HPS police cruiser about two seconds behind, with its emergency lighting, but no siren, activated. CW #24 estimated that both vehicles were travelling at the same speed, which he placed at about 80 to 100 km/h, with the police cruiser about ten to 20 feet behind the ATV. CW #24 advised that he did not see any pedestrians at that time. Within seconds of the vehicles racing past his location, CW #24 heard a loud bang.

The third and fourth witnesses on 13th Street, CW #19 and CW #17, made their observations from the same vantage point on 6th Avenue, south of 12th Street, approximately mid-way between 12th and 10th Streets.

CW #19 described that she heard what she initially thought was a motor-bike travelling southbound on 6th Avenue at about 80 km/h. She described the conditions as dark with no artificial lighting, the roads were dry and the weather was clear. She described the ATV as having no lighting. CW #19 then observed a police cruiser also travelling southbound and within seconds, heard a loud crash. CW #19 stated that after the crash, she observed the police officer stop his vehicle, put on his lights and run across the street. She indicated that until he put his lights on, she had been unaware that the second vehicle was a police car. CW #19 is the only witness on 6th Avenue who did not notice that the SO had his emergency lighting system activated as he pursued the Complainant on his ATV. CW #17, who was with CW #19, immediately observed the red and blue emergency lighting on the HPS cruiser, but no siren, as it approached her location travelling southbound on 6th Avenue, toward 10th Street. She described the road conditions as dry, the weather clear and, although it was dark out, the intersection of 6th Avenue and 10th Street was clearly visible due to artificial lighting. Almost instantaneous with CW #17’s observation of the police cruiser passing, she heard a loud bang.

The fifth and last witness to observe the ATV and the police cruiser on 6th Avenue, prior to the collision, was CW #21, who was in the same general location as CW #19 and CW #17, described hearing a siren coming from the north, sounding intermittently, and observed an ATV driving southbound on 10th Street with a rear brake light visible. He described the road conditions as dry and it was clear but dark out. CW #21 described seeing a police cruiser following the ATV, with its emergency lighting activated, but no siren, at a distance of approximately 20 feet and both vehicles were travelling at a speed of 10 to 15 km/h. The ATV failed to stop at the stop sign at the intersection with 6th Avenue, where it made contact with a westbound vehicle.

The next reading provided from the cruiser’s GPS/AVL data recorder is at 9:22:42 pm, when the cruiser is just marginally north of the intersection with 10th Street, where the collision occurred, and the speed of his cruiser is recorded as 28.97 km/h, which is consistent with the observations of CW #21 as to the slowing of both vehicles just prior to the intersection.

Fifteen seconds later, at 9:22:57 p.m., the SO’s cruiser is stationary at the collision scene. At 9:23 p.m., the SO is heard on the police communications recording indicating that he needs EMS “right now!” As such, it is clear, that from the time that the SO began to follow the ATV, until the collision, no more than 60 seconds had elapsed.

The CCTV video from a commercial premises on 10th Street confirmed that the SO’s cruiser arrived with its emergency lights flashing as it arrived at the scene from the north, immediately following the collision. I have reviewed the video many times, as the location of the intersection of 10th Street and 6th Avenue is one block from the intersection of 10th Street and 7th Avenue, where the store is located. Upon my review, it appears that there is a passage of less than one second between when the Chrysler driven by CW #5 appears to spin out and the emergency lighting system is seen at the intersection of the collision. What is further clear from the video, is that there is a steady stream of traffic in the area, as well as a number of pedestrians.

On all of this evidence, then, I accept that when the SO initially entered his motor vehicle and followed the Complainant, he had not yet activated his emergency lighting system, but as he continued on 13th Street, and then onto 6th Avenue, it is clear that six of the seven witnesses clearly observed the police cruiser to have its emergency lighting system activated, with only CW #19 being of the view that he only turned on his lights when he arrived at the intersection where the collision occurred. Since both CW #17 and CW #21 had the same vantage point as did CW #19, and their evidence is consistent with that of the other four witnesses who observed the pursuit, I accept that the SO did in fact have his emergency lighting activated while he was pursuing the ATV, and that CW #10 was obviously mistaken in this regard.

Based on the evidence of these eight witnesses, I also accept that the SO was in a vehicle pursuit of the Complainant, that both vehicles were driving at excessive rates of speed, with the exception of when they approached the intersection of 6th Avenue and 10th Street, when CW #21 estimated their speed as having slowed to only 15 to 20 km/h. I also accept that the SO’s police cruiser was in close proximity to the rear of the ATV, with distances estimated at no more than the length of one to two houses (CW #13), and as close as within a few feet (CW #1), while other witnesses put the distance at either of 10 to 20 feet (CW #24) or at 20 feet (CW #21).

On all of the evidence, there is no dispute that the weather on April 1st was clear, the roads were dry, and it was dark out during the police pursuit of the Complainant, with visibility dependent on the amount of artificial lighting in the area, with some having very poor visibility while others, like the intersection of 6th Avenue and 10th Street, being quite well illuminated. The entire route that the Complainant was followed by the SO was primarily a residential neighbourhood.

While only CW #24 talked about other traffic in the area, and commented that there were no pedestrians at the point when he observed the ATV and the SO, I note that at the very least CW #20, CW #1, and CW #11, were on foot at the time, with CW #11 indicating that he had to jump out of the way as he feared that he would be struck by the police cruiser.

With respect to vehicular traffic, in addition to CW #5’s vehicle, which was struck by the ATV, at the very least, there were at least two other cars in the immediate area of the collision, that being the motor vehicle driven by CW #4, with two occupants, and the motor vehicle driven by CW #7, with two occupants. I also note that the pizza restaurant at the corner where the collision occurred was operating at the time, and one would have expected at the very least vehicular traffic, if not pedestrian traffic, either picking up or delivering orders.

While there were an additional six CWs at or near the point of collision, none were able to describe the driving of either of the ATV or the police cruiser prior to the collision, which drew their attention to the area. Of those six witnesses, CW #5, who was struck by the ATV, described the police cruiser as already being there when he exited his vehicle, while CW #3 and CW #4, who were travelling behind CW #5’s vehicle, described their first observation of the police cruiser as either five to eight seconds (CW #3) or six seconds (CW #4) after the collision.

CW #7, who was travelling eastbound on 10th Street with her husband, estimated that she first saw the cruiser 15 to 30 seconds after the bang, while CW #16 estimated that she observed the first police cruiser arrive within one to two seconds of the collision and that the cruiser had its emergency lighting activated. As indicated earlier, the CCTV confirms the evidence of CW #16, in that it reveals that within one second of the collision, the SO was already at the intersection with his emergency lighting activated.

While no other police officer observed either the pursuit, or the ensuing collision, WO #3 stated that he was told by the SO that he had been following the ATV with his emergency lights on when the ATV disobeyed the stop sign and collided with CW #5’s motor vehicle. WO #4 advised that he was told by the SO that he had been trying to stop the ATV, but he gave no further details.

WO #1 indicated that he too heard the information over the radio about the complaint that an ATV with no headlights had been driving up and down the road in the area of 9th Avenue and 10th Avenue in Hanover. The next transmission he heard was the SO stating that he required an ambulance as a result of an officer-involved motor vehicle collision; at no time did WO #1 hear any transmission indicating that the SO was in a pursuit. While WO #1 stated that when the SO started to tell him about what had led up to the collision, he had told him to shut up, WO #3 indicated that WO #1 told him that the SO had chased the ATV.

WO #2, of the West Gray Police Service, stated that he too heard the radio call about an ATV being driven on someone’s lawn, and later heard a distressed call from an HPS officer which he could not make out but was able to determine, by calling the police dispatcher by cell phone, related to a collision between the ATV and a motor vehicle. WO #2 stated that the SO later twice told him, at the collision scene, that he had been unable to get on the air, meaning he could not communicate with the police communications centre.

On all of the evidence, it is clear that the Complainant was operating an ATV on residential streets in the Town of Hanover, in contravention of their by-laws, and he did not have the appropriate lamps illuminated on his vehicle after dusk. As such, the SO would have been acting lawfully and within his duties, had he attempted to make a vehicle stop in order to investigate the Complainant for these offences.

While there is no evidence as to what preceded the collision from either of the Complainant or the SO, I infer from the fact that the SO was pursuing the Complainant, and the fact that he had his emergency lighting system activated, that the SO was indeed attempting to stop the Complainant.

On a review of all of the evidence, I have no difficulty in concluding that the SO was, at some point, involved in a police pursuit with the ATV being operated by the Complainant and that he was in breach of the Ontario Police Services Act (OPSA) legislation, as well as the companion HPS Regulation entitled ‘Suspect Apprehension Vehicle Pursuits’ for the following reasons:

Pursuant to Ontario Regulation 266/1 of the OPSA entitled Suspect Apprehension Pursuits:

2 (1) A police officer may pursue, or continue to pursue, a fleeing motor vehicle that fails to stop,

- If the police officer has reason to believe that a criminal offence has been committed or is about to be committed; or

- For the purposes of motor vehicle identification or the identification of an individual in the vehicle.

(2) Before initiating a suspect apprehension pursuit, a police officer shall determine that there are no alternatives available ….

(3) A police officer shall, before initiating a suspect apprehension pursuit, determine whether in order to protect public safety the immediate need to apprehend an individual in the fleeing motor vehicle or the need to identify the fleeing motor vehicle or an individual in the fleeing motor vehicle outweighs the risk to public safety that may result from the pursuit.

(4) During a suspect apprehension pursuit, a police officer shall continually reassess the determination made under subsection (3) and shall discontinue the pursuit when the risk to public safety that may result from the pursuit outweighs the risk to public safety that may result if an individual in the fleeing motor vehicle is not immediately apprehended or if the fleeing motor vehicle or an individual in the fleeing motor vehicle is not identified.

Pursuant to the companion regulations issued for the Hanover Police Service, entitled “Suspect Apprehension Vehicle Pursuits” under Paragraph C: Policy Statement:

1. GENERAL

- Public safety and the safety of officers is the paramount consideration in any decision to initiate, continue, or discontinue a suspect apprehension pursuit;

- Public safety represents a balance, which may change rapidly and must be continually assessed.

- A suspect apprehension pursuit is the choice of last resort and will be considered only when other alternatives are unavailable or unsatisfactory. (Bolding is in the regulation, not added by me).

- Suspect apprehension pursuits may be initiated where the police officer has reason to believe that a serious criminal offence has been or is about to be committed and the pursuit is necessary for the motor vehicle identification or the identification of an individual in the motor vehicle. (Bolding is mine).

- In cases involving suspected non-criminal offences, suspect apprehension pursuits may be initiated for the purpose of identifying the vehicle or a person in the vehicle. In these cases, suspect apprehension pursuits shall be discontinued upon vehicle identification or identification of the person in the vehicle.

3. SPECIAL RESTRICTIONS

- Officers will NOT pursue motorcycles or All Terrain vehicles unless the officer believes on reasonable and probable grounds that to do so is necessary to immediately protect against loss of life or serious bodily harm.

[All capital letters and bolding is contained in the regulation and was not added by me].

Based on these provisions, which are clearly meant to reduce or eliminate serious bodily harm or death caused by police pursuits, the SO’s actions ran afoul of both the provincial legislation and the companion general order put out by his own police service.

The SO observed an ATV being operated on Hanover streets, in contravention of the by-laws, and without the appropriate operating lamps, contrary to the Highway Traffic Act (HTA) and, according to the evidence of CW #20, he began to follow the ATV presumably for the purpose of pulling it over and initiating a traffic stop. At no time did he have any grounds to believe that a criminal offence had been committed. While it was discovered after the fact that the ATV being driven by the Complainant was in fact stolen, it is clear from the radio silence from the SO from the point where he first started to follow the Complainant to the subsequent collision, that at no time did he request any information about the ATV and as such, it is clear that he did not have that information at the time and it could not, therefore, be used to justify a pursuit in this fact scenario.

The SO pursued the Complainant on the ATV from the point where he had re-entered his cruiser on 8th Avenue at approximately 9:21:57 p.m., until the Complainant’s vehicle crashed at approximately 9:22:57 p.m., and at no time did he contact the communications centre to advise that he was involved in a pursuit, despite the fact that he had been pursuing the Complainant’s vehicle on municipal streets in the Town of Hanover at speeds described by three independent witnesses, who observed the cruiser travelling southbound on 10th Street, as travelling at ‘high speeds’ (CW #11), travelling at approximately 80 to 90 km/h (CW #1) or between 80 to 100 km/h (CW #24) for almost an entire minute prior to contacting the dispatcher. Semantics aside, there can be no confusion that a cruiser travelling at that rate of speed following a motor vehicle is clearly in a pursuit.

The SO had an obligation to report to the dispatcher that he was engaged in a pursuit as soon as it was initiated. While I have some hearsay evidence from WO #2 that the SO told him that he had been unable to get on the air, I note that WO #2, in order to avoid tying up the communications line himself, used his cell phone and was immediately able to make contact with the dispatcher, which was clearly an option open to the SO as well. Furthermore, if the SO was unable to get on the air, it was his obligation to discontinue the pursuit, not to carry on without the input of the Supervisor.

This pursuit involved an ATV, which the HPS General Order clearly specifies are not to be involved in vehicle pursuits unless ‘the officer believes on reasonable and probable grounds that to do so is necessary to immediately protect against loss of life or serious bodily harm’. While we are without the benefit of the SO’s thinking in this regard, I cannot imagine that any right thinking police officer would think that it was necessary to pursue an ATV in a residential area, at high rates of speed, while following very closely behind the vehicle, in poorly lit conditions, while the ATV is without the benefit of headlights, in order to investigate the driver for a by-law infraction and/or an equipment infraction under the HTA.

The legislation puts the onus on the officer involved in the pursuit to continually reassess the situation and he or she ‘shall discontinue the pursuit when the risk to public safety that may result from the pursuit outweighs the risk to public safety that may result if an individual in the fleeing motor vehicle is not immediately apprehended or if the fleeing motor vehicle or an individual in the fleeing motor vehicle is not identified’.

Further, I cannot imagine any reasonable person believing that issuing a ticket for a by-law infraction and/or an HTA equipment infraction would have outweighed the risk to public safety of continuing to pursue an ATV at the speeds which the SO did, especially in light of the fact that the offences for which the SO presumably initially wanted to initiate a traffic stop were insignificant compared to the speeds reached by both the Complainant and the SO during the pursuit.

Pursuant to the Suspect Apprehension Pursuits legislation, ‘a suspect apprehension pursuit occurs when a police officer attempts to direct the driver of a motor vehicle to stop, the driver refuses to obey the officer and the officer pursues in a motor vehicle for the purpose of stopping the fleeing motor vehicle’. While we are without evidence as to what preceded the SO pursuing the Complainant on an ATV at ‘high speeds’, and there were no communications from the SO during the pursuit up to and including the collision which might shed some light on the matter, I can see no reason to chase a vehicle at those same high speeds for any other purpose than to attempt to stop it.

Having said all of that, however, a failure to comply with the OPSA does not equate with reasonable grounds to believe that a criminal offence has been committed.

The question to be determined is whether or not there are reasonable grounds to believe that the SO committed a criminal offence, specifically, whether or not his driving rose to the level of being dangerous and therefore in contravention of s.249(1) of the Criminal Code and did thereby cause bodily harm contrary to s.249(3).

Pursuant to the Supreme Court of Canada in R. v. Beatty, [2008] 1 S.C.R. 49, s.249 requires that the driving be “dangerous to the public, having regard to all of the circumstances, including the nature, condition and use of the place at which the motor vehicle is being operated and the amount of traffic that, at the time, is or might reasonably be expected to be at that place” and the driving must be such that it amounts to “a marked departure from the standard of care that a reasonable person would observe in the accused’s circumstances”.

In applying the reasonable person test, I must consider if the SO’s driving was a marked departure from the standard of care that a reasonable person in his circumstances would observe. As such, I must determine if his driving amounted to a marked departure from that of a police officer attempting a vehicle stop of an ATV for a by-law infraction and an equipment violation of the HTA.

Since, on the evidence before me, I have reasonable grounds to believe that the SO was involved in a vehicle pursuit with an ATV, which is strictly forbidden pursuant to the HPS General Order unless he had reasonable grounds to believe that death or serious bodily harm was imminent, and that he failed to contact a supervisor before initiating or continuing the pursuit, and that he failed to reassess the situation and determine that to continue driving at those excessive speeds, in a residential area with pedestrian and vehicular traffic, on a dark night with insufficient artificial lighting, while pursuing an ATV that did not have headlamps, I undoubtedly have reasonable grounds to believe that the SO’s pursuit of the ATV contravened both the provincial legislation and the HPS legislation. As indicated previously, however, a breach of the OPSA, or HPS policy, does not necessarily equate with it being “a marked departure from the standard of care that a reasonable person would observe in the accused’s circumstances;” something more being required in order to bring the driving of the SO within the realm of criminal sanctions.

On a review of all of the evidence, it is clear that the SO was likely travelling at a rate of speed estimated as being in the area of 40 to 50 km/h in excess of the speed limit when he pursued the ATV being operated by the Complainant. Furthermore, based on the witness evidence, it is clear that there was both other vehicular and pedestrian traffic in the area and the night was dark, with many areas without adequate artificial lighting. In fact, CW #11 specifically indicated that he had to jump out of the way as he feared that he would be struck by the police cruiser.

It is not disputed, however, that the weather was clear, but dark, and the roads were dry.

While the pursuit was carried out on municipal roads and in a residential area, and the Complainant’s ever increasing speeds appeared to be in direct correlation to his desire to evade police, I find that ultimately it was the voluntary decision of the Complainant to try to outrun police and, in doing so, he fled at a dangerous rate of speed with no regard for other people using the highway, he disobeyed a stop sign at the intersection of 6th Avenue and 10th Street, and he ultimately was the cause of the collision which caused his injuries.

While I hope that in summarizing the SO’s driving above I have adequately conveyed my strong disapproval of his actions, not only in initiating a pursuit of an ATV on the streets of the Town of Hanover in the first instance, which is directly prohibited by the HPS policy with respect to suspect apprehension pursuits, but also in attaining the speeds that he did in attempting to stop the Complainant in order to investigate him for infractions of the town by-laws and an equipment infraction of the HTA. I find however, that the evidence falls short of that required to satisfy me that I have reasonable grounds to believe that the SO ran afoul of the Criminal Code or that his driving rose to the level required to meet the necessary elements for dangerous driving.

While I find, with some hesitancy, that I lack those grounds, I do so for the following reasons:

There is no evidence that the SO, at any time, disobeyed any traffic controls, with the evidence of CW #1 specifically indicating that the SO took the turn from 13th Street onto 6th Avenue in a controlled manner and at a speed which she estimated at being in the area of 40 km/h. This evidence is specifically confirmed by the GPS data wherein the SO’s vehicle is clocked travelling at 40 km/h just south of that intersection;

There is no evidence that vehicular traffic was ever interfered with, or obstructed by, the driving of the SO;

The evidence of CW #21 that he observed the SO’s vehicle as having slowed to approximately 10 to 15 km/h as he approached the intersection of 6th Avenue and 10th Street, which is confirmed by the GPS data presumably taken just prior to that observation, which clocked the SO as already having reduced his speed to 28 km/h;

The evidence of CW #21 that the ATV then ran the stop sign, without stopping at the intersection of 6th Avenue and 10th Street, while the SO did not;

The evidence that the high speeds of the SO’s vehicle, as observed by CW #1, CW #11 and CW #24, as he was travelling southbound on 6th Avenue, lasted no more than a mere matter of seconds, at which point, I surmise from the officer’s slowing of his vehicle, that the SO reconsidered his options and chose to discontinue the ill-considered pursuit and he drastically reduced his speed. This evidence is positively confirmed by the GPS data, wherein the speed of the cruiser is registered at 40 km/h just south of 13th Street, and is registered again just north of 10th street as having been significantly reduced to 28 km/h. I take from this evidence that the SO, either in order to discontinue the pursuit, or knowing that a traffic controlled intersection was ahead, opted to give up on his pursuit in favour of public safety, and he significantly reduced the speed of his motor vehicle;

In all, the SO’s lapse of judgment appears to have lasted no more than approximately ten seconds and no more than, at most, 300 metres;

While the SO failed to notify the dispatcher that he was in a vehicular pursuit, I take into consideration that there is some evidence that the SO was unable to make contact with the dispatcher, due to heavy air traffic; and, finally

It was the voluntary choice of the Complainant in operating the ATV in the dangerous fashion that he did, without the aid of headlamps, in a poorly lit area, at high speeds, in order to evade police and he is ultimately responsible for the subsequent collision for which he has paid an extremely high price. As such, I am unable to establish a causal connection between the actions of the SO, who slowed for the intersection at 6th Avenue and 10th Street, and the injuries to the Complainant, who continued on into the intersection, after failing to stop at the stop sign, and unfortunately colliding with the vehicle driven by CW #5.

In coming to my conclusion, I have reminded myself of the jurisprudence of the Supreme Court of Canada that I am not to hold police to an unattainable standard of perfection, as enunciated in their decision in R v Nasogaluak [2010] 1 S.C.R. 206, as follows:

Police actions should not be judged against a standard of perfection. It must be remembered that the police engage in dangerous and demanding work and often have to react quickly to emergencies. Their actions should be judged in light of these exigent circumstances.

As well as their pronouncement in R v Roy (2012), 281 C.C.C. (3d) 433, wherein the Supreme Court of Canada held that a simple misjudgment could not reasonably support an inference of a marked departure, as follows:

A fundamental point in Beatty is that dangerous driving is a serious criminal offence. It is, therefore, critically important to ensure that the fault requirement for dangerous driving has been established. Failing to do so unduly extends the reach of the criminal law and wrongly brands as criminals those who are not morally blameworthy. The distinction between a mere departure, which may support civil liability, and the marked departure required for criminal fault is a matter of degree. The trier of fact must identify how and in what way the departure from the standard goes markedly beyond mere carelessness.

And further:

Simple carelessness, to which even the most prudent drivers may occasionally succumb, is generally not criminal. As noted earlier, Charron J., for the majority in Beatty, put it this way: "If every departure from the civil norm is to be criminalized, regardless of the degree, we risk casting the net too widely and branding as criminals persons who are in reality not morally blameworthy" (para. 34). The Chief Justice expressed a similar view: "Even good drivers are occasionally subject to momentary lapses of attention. These may, depending on the circumstances, give rise to civil liability, or to a conviction for careless driving. But they generally will not rise to the level of a marked departure required for a conviction for dangerous driving" (para. 71).

And lastly:

Driving which, objectively viewed, is simply dangerous, will not on its own support the inference that the accused departed markedly from the standard of care of a reasonable person in the circumstances (Charron J., at para. 49; see also McLachlin C.J., at para. 66, and Fish J., at para. 88). In other words, proof of the actus reus of the offence, without more, does not support a reasonable inference that the required fault element was present. Only driving that constitutes a marked departure from the norm may reasonably support that inference.

I have also carefully considered the decision of our Court of Appeal in R v Pezzo, [1972] O.J. No. 965, that excessive speed alone does not necessarily equate with dangerous driving. The following is an excerpt from that case, in which the Court found that the offence of dangerous driving was not made out despite the extremely high rate of speed at which the Appellant was travelling at the time:

With respect to the dangerous driving there is very little evidence. The Crown gave particulars of the dangerous driving and restricted itself to excessive speed. My brother Arnup and I are of the opinion that on the scanty evidence presented it would be unsafe to maintain a conviction. The learned trial Judge said:

- "On all the evidence before me I find that you took this car, had it in your possession, stole it, were driving it. The car tipped over, on the evidence before me, after a skid mark of some 98 feet, flipped over on its back ... for another 42 feet skid mark which indicates a great deal of speed, a collision with the wall. On all the evidence before me I find you guilty of the charge of theft of a motor vehicle and dangerous driving."

With respect to the learned trial Judge we are not satisfied that the evidence clearly discloses that the appellant was driving in such a manner that the driving can be characterized as dangerous driving within the meaning of the relevant section of the Code. We would accordingly allow the appeal against conviction and direct an acquittal on the charge of dangerous driving.

And the subsequent decision in R v M.K.M., [1998] O.J. No. 1601, that in certain circumstances, excessive speed alone may be sufficient to establish dangerous driving:

Depending on the context in which it occurred, excessive speed can amount to a marked departure from the standard of care of a prudent driver. Here the context included the following: the accident occurred on a busy highway in a built up area of Mississauga, and just before the accident the appellant had been driving aggressively and engaging in "horseplay" on the road with her co-accused. Although their estimates of the appellant’s driving speed varied, all of the independent witnesses testified that she was driving too fast. The evidence of … all supported the trial judge’s conclusion that the appellant was driving well above the speed limit and too quickly to avoid any unexpected occurrence on the highway. Indeed, Miss Black gave evidence that the appellant lost control of her car because she was driving too fast.

Having fully considered the edicts from our Court of Appeal as to the factors to consider in assessing whether or not I have reasonable grounds to believe that there is sufficient evidence to make out a charge of dangerous driving, with some reluctance, I do not find that it is made out on this record.

Taking into account that the only evidence that I have which would support a charge of dangerous driving would be that of a high rate of speed

As such, while I am hopeful that the concerns expressed will be adequately addressed within the HPS in order that an incident such as this will not recur, I am unable to find that I have reasonable grounds to cause a charge of dangerous driving to be laid in this instance, and none shall issue.

Date: April 6, 2018

Original signed by

Tony Loparco

Director

Special Investigations Unit

Footnotes

- footnote[1] Back to paragraph The cruiser admittedly at one point caused CW #11 to jump out of the way because CW #11 thought he might get hit by the cruiser. Notwithstanding this fact, CW #11 was of the opinion that the police were just doing their job, pursuing an ATV driving on the road with no headlights.