Small-mouthed Salamander Recovery Strategy

This document is the recovery strategy for a species at risk – the Small-mouthed Salamander.

About the Ontario recovery strategy series

This series presents the collection of recovery strategies that are prepared or adopted as advice to the Province of Ontario on the recommended approach to recover species at risk. The Province ensures the preparation of recovery strategies to meet its commitments to recover species at risk under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) and the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk in Canada.

What is recovery?

Recovery of species at risk is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened, or extirpated species is arrested or reversed, and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of a species’ persistence in the wild.

What is a recovery strategy?

Under the ESA a recovery strategy provides the best available scientific knowledge on what is required to achieve recovery of a species. A recovery strategy outlines the habitat needs and the threats to the survival and recovery of the species. It also makes recommendations on the objectives for protection and recovery, the approaches to achieve those objectives, and the area that should be considered in the development of a habitat regulation. Sections 11 to 15 of the ESA outline the required content and timelines for developing recovery strategies published in this series.

Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for endangered and threatened species within one or two years respectively of the species being added to the Species at Risk in Ontario list. There was a transition period of five years (until June 30, 2013) to develop recovery strategies for those species listed as endangered or threatened in the schedules of the ESA. Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for extirpated species only if reintroduction is considered feasible.

What’s next?

Nine months after the completion of a recovery strategy a government response statement will be published which summarizes the actions that the Government of Ontario intends to take in response to the strategy.

The implementation of recovery strategies depends on the continued cooperation and actions of government agencies, individuals, communities, land users, and conservationists.

For more information

To learn more about species at risk recovery in Ontario, please visit the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry Species at Risk webpage.

Recommended citation

Hamill, Stewart E. 2015. Recovery Strategy for the Small-mouthed Salamander (Ambystoma texanum) in Ontario. Ontario Recovery Strategy Series. Prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, Peterborough, Ontario. vi + 18 pp.

© Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2015

ISBN 978-1-4606-3084-6 (PDF)

Cette publication hautement spécialisée « Recovery strategies prepared under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 », n’est disponible qu’en Anglais en vertu du Règlement 411/97 qui en exempte l’application de la Loi sur les services en français. Pour obtenir de l’aide en français, veuillez communiquer avec Michelle Collins au ministère des Richesses naturelles au

Author

Stewart E. Hamill – Wildlife Biologist, Merrickville

Acknowledgments

My contacts at the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry (OMNRF) office in Peterborough, Megan McAndrew and Amelia Argue, Species at Risk Biologists, assisted with guidance and information for this project. I would also like to thank those who reviewed and commented on the drafts. The individuals listed below provided details on the species, the locations where it occurs and the habitat, and on threats.

Karine Bériault

Species at Risk Biologist, OMNRF

Vineland, ON

James Bogart

Professor Emeritus, University of Guelph

Guelph, ON

Joe Crowley

Herpetology Species at Risk Specialist, OMNRF

Peterborough, ON

Ron Gould

Zone Ecologist, OMNRF

Aylmer, ON

David Green

Director, Redpath Museum, McGill University

Montreal, QC

Michael Oldham

Botanist/Herpetologist Natural Heritage Information Centre, OMNRF

Peterborough, ON

John Urquhart

Conservation Science Manager, Ontario Nature

Toronto, ON

Allen Woodliffe

District Ecologist (retired), OMNRF

Chatham, ON

Declaration

The recovery strategy for the Small-mouthed Salamander was developed in accordance with the requirements of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA). This recovery strategy has been prepared as advice to the Government of Ontario, other responsible jurisdictions and the many different constituencies that may be involved in recovering the species.

The recovery strategy does not necessarily represent the views of all of the individuals who provided advice or contributed to its preparation, or the official positions of the organizations with which the individuals are associated.

The goals, objectives and recovery approaches identified in the strategy are based on the best available knowledge and are subject to revision as new information becomes available. Implementation of this strategy is subject to appropriations, priorities and budgetary constraints of the participating jurisdictions and organizations.

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this strategy.

Responsible jurisdictions

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry

Environment Canada – Canadian Wildlife Service, Ontario

Executive summary

The Small-mouthed Salamander is a medium to large salamander classified as endangered on the Species at Risk in Ontario List. It spends most of its adult life in underground burrows or under leaf litter, or living under cover objects such as logs and rocks. In early spring the adults make an annual nocturnal overland migration to breeding wetlands for mating and egg-laying. The larvae remain in water until emergence as adults in mid-summer.

Habitat requirements include an integrated complex with:

- a shallow fish-free wetland which can retain water until mid-summer;

- surrounding habitat which provides cover for migration and adult life;

- shaded soft moist soils for burrowing; and

- habitat connections which permit dispersal and longer migrations of up to one km.

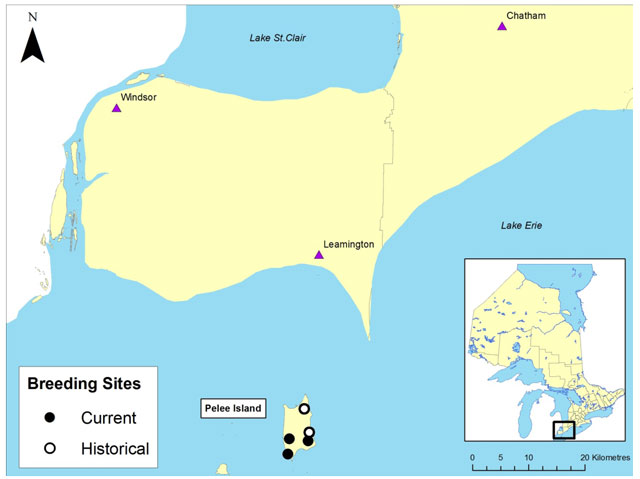

The Small-mouthed Salamander reaches the northern limit of its range in Michigan, Ohio and on Pelee Island in Ontario. On Pelee Island it is known from only three wetlands, two of which are protected. The third site is on private land. Due to the relative isolation of the island, monitoring and surveillance programs are not frequent, no comprehensive population census data are available and threat assessment is limited. Nevertheless, the abilities of the species to withstand temporary droughts and avoid predators mean that this salamander could continue to thrive in Ontario if its habitat is maintained.

Threats to the Small-mouthed Salamander in Ontario include:

- habitat alteration, loss, and fragmentation;

- invasive and introduced species, such as the European Common Reed (Phragmites australis ssp. australis), the Emerald Ash Borer (Agrilus planipennis) and fish introduced to breeding ponds;

- climate change, which could bring warmer, drier conditions with prolonged drought;

- pollution, which is a particular threat to salamanders due to their sensitivity;

- predation, particularly by the recently-introduced Wild Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) which could be an effective salamander predator;

- mortality on roads from vehicles; and

- competition and hybridization, although the species appears to be capable of managing this threat.

The recovery goal is to ensure that threats to populations and habitat are sufficiently managed to allow for long-term persistence and expansion of the Small-mouthed Salamander population within its Ontario range on Pelee Island. The strategy describes protection and recovery objectives for this species in Ontario, including to:

- protect and maintain the quality and quantity of habitat on Pelee Island where the Small-mouthed Salamander occurs;

- implement a monitoring program for salamander populations, habitats, and threats on Pelee Island including surveys of suitable habitat;

- promote and carry out research on Small-mouthed Salamander genetics, populations and threats;

- investigate existing, former, and potential Small-mouthed Salamander habitats on Pelee Island to determine if restoration, re-introduction or population interventions would be appropriate; and

- implement education, stewardship and communication programs for private landowners, residents and visitors on Pelee Island.

This recovery strategy also recommends that a habitat regulation be developed which includes:

- all wetland habitats where the Small-mouthed Salamander is known to breed;

- any new locations found or any locations where the salamander is re-introduced;

- all suitable terrestrial areas and features that extend radially 300 m from the edge of any breeding wetland; and

- corridors that provide contiguous connections between breeding locations extending up to a maximum of one kilometre.

1.0 Background information

1.1 Species assessment and classification

- Common name: Small-mouthed Salamander

- Scientific name: Ambystoma texanum

- SARO List Classification: Endangered

- SARO List History: Endangered (2008), Endangered – Not Regulated (2005), Threatened (2004)

- COSEWIC Assessment History: Endangered (2004), Special Concern (1991)

- SARA Schedule 1: Endangered (July 27, 2005)

- Conservation status rankings:

- GRANK: G5 NRANK: N1 SRANK: S1

The glossary provides definitions for technical terms, including the abbreviations above.

1.2 Species description and biology

Species description

The Small-mouthed Salamander (Ambystoma texanum) is a typical member of the Mole Salamander family (Ambystomatidae), being a medium to large salamander (maximum length 18 cm) with prominent costal grooves, robust limbs and body and a broad head (Harding 1997). The head in this species, however, is noticeably smaller than that of other mole salamanders and the snout is short and blunt. The back is black or very dark brown and the belly is black with a few light spots. The flanks and the long tail are covered with light grey-blue flecking (Petranka 1998). The adult Small-mouthed Salamander resembles the sympatric Blue-spotted Salamander (Ambystoma laterale) adult although the latter species usually has blue spots rather than grey flecks on the body. The adult Small-mouthed Salamander also has a proportionally smaller head (MacCulloch 2002).

Larvae are much smaller than adults and have external gills and a large fin on the tail. Identification of larvae is difficult because adult colouring develops only when juveniles leave the water as adults (MacCulloch 2002).

Species biology

The common family name “mole” salamander refers to the habit of usually staying underground or beneath cover objects except when breeding. In early spring (late March or early April) the adults migrate overland at night to shallow fish-free bodies of water for mating and egg-laying. Fertilization is internal. The female lays 200 to 300 eggs individually or in small groups, on dead leaves and twigs on the bottom of the breeding pond. The eggs hatch after 9 or 10 days to aquatic gilled larvae that transform three months later, by mid-summer (June or July), to terrestrial adults. Adult salamanders reach breeding age two years after metamorphosis (Government of Canada 2012, Harding 1997). After breeding activities, the adults return to their underground or under cover haunts where they also spend the winter in hibernation.

The only location where the Small-mouthed Salamander is found in Canada is Pelee Island, in Ontario. This habitat is shared with another Ambystoma species, the Blue- spotted Salamander, and with a group of unisexual female polyploid Ambystoma salamanders (King et al. 1997) which are more common than the pure Small-mouthed Salamander (Bogart and Licht 2004). These polyploids have a unique mode of reproduction involving heterosexual mating and asexual development of the egg, but with incorporation of the genome from the sperm which increases the chromosome complement to diploid (double), triploid (triple), or even tetraploid (quadruple) (Bogart and Licht 2004). Molecular studies (Bogart et al. 1985, Bogart and Licht 1986, Bogart et al. 1987, Bi and Bogart 2010) suggest that the original unisexual polyploids on Pelee Island were not produced through crosses involving the two species there (A. laterale and A. texanum). Apparently, they were isolated on the island at the same time as the two pure species and now exchange nuclear genomes with those two species. Small- mouthed Salamander DNA can make up anywhere from a minority to a majority of the unisexual polyploid genome, and unisexual salamanders can thus resemble the Small- mouthed Salamander. The polyploids on Pelee Island are all females and each must mate with a male Small-mouthed or Blue-spotted Salamander for reproductive success (Hedges et al. 1992). These Pelee Island polyploid hybrids are more correctly called ‘unisexuals’ as they are not true hybrids.

Unisexual salamander larvae are larger than Blue-spotted and Small-mouthed Salamander larvae (Wilbur 1972). These larger unisexual larvae have been observed to attack and bite the smaller larvae of both of those species in artificial ponds (Brodman and Krouse 2007). The result was reduced survival and growth of Small- mouthed Salamander larvae in the presence of unisexual larvae. However this effect was less than the effect of competition with other Small-mouthed Salamander larvae. When raised with unisexuals, Small-mouthed Salamander larvae spent more time concealed in vegetation and were able to minimize the effects of competition and predation (Brodman and Krouse 2007).

Adult Small-mouthed Salamanders feed on insects, slugs and earthworms, while larvae eat a variety of small aquatic invertebrates. The larvae are eaten by crayfish, predaceous aquatic insects, birds and snakes, while adults are consumed by snakes and other vertebrate predators (Harding 1997).

1.3 Distribution, abundance and population trends

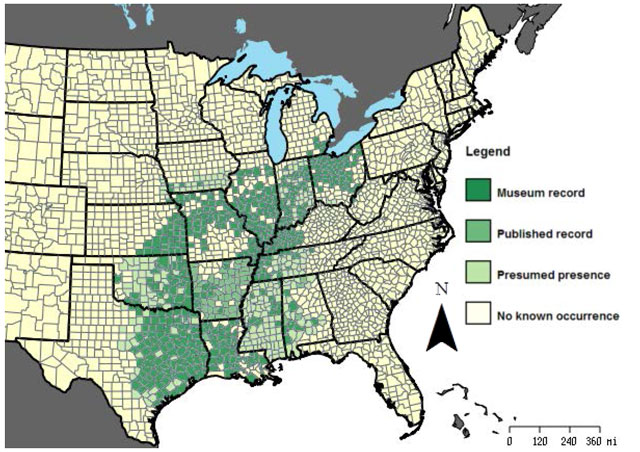

The Small-mouthed Salamander is primarily a central southern United States species, ranging from Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi and western Alabama north to extreme southeastern Michigan, northern Ohio (including islands in Lake Erie) and Pelee Island in Ontario (Bogart and Licht 2004).

The abundance and status of the species range from widespread, common and secure in southern portions of the range, to rare and endangered at its northern limit in Michigan and Ontario (Harding 1997). The only location for the species in Canada and Ontario is Pelee Island in Lake Erie.

In 1991 the Small-mouthed Salamander occupied five breeding sites on Pelee Island (Bogart and Licht 1991). By the year 2000 two of these had been eliminated by development activities and the permanent loss of water (Bogart and Licht 2004). Three breeding locations with surrounding woodland habitat remain:

- a flooded woodlot within the provincial Fish Point Nature Reserve;

- a flooded woodlot on a nature reserve jointly owned by Ontario Nature, Essex Region Conservation Authority and the Nature Conservancy of Canada; and

- a pond on private land.

It is impossible to determine the density of “pure” populations of Small-mouthed Salamander or to assess trends due to the difficulties associated with identification in the field. Collections by J. Bogart and L. Licht on Pelee Island in 2000 indicate that unisexuals made up 78 percent of the population, but there are currently no population estimates (Government of Canada 2012).

1.4 Habitat needs

In Ontario, the Small-mouthed Salamander is found in several types of moist habitats, including tall-grass prairies (Ecological Land Classification (ELC) unitTP), dense hardwood forests (ELC unit FOD) and agricultural lands (ELC unit CU) if such areas provide suitable breeding ponds (Government of Canada 2012). These habitats must also have soils soft enough to enable adults to find burrows, such as those created by crayfish.

Shallow fish-free bodies of water are needed by the Small-mouthed Salamander for breeding activities including mating and egg-laying. Suitable water bodies are usually less than a metre in depth and contain woody debris, submerged grasses and reeds, and emergent vegetation. These water bodies must retain water throughout the larval stage which normally lasts from March through July (Bogart and Licht 2004). At times other than the spring breeding season the adults generally remain hidden underground in soft moist (shaded) soils or beneath rotting logs, rocks or leaf litter (Harding 1997). Like other mole salamanders, adult Small-mouthed Salamanders retreat below the frost line into deep rock fissures and rodent burrows (Jefferson Salamander Recovery Team 2009) during the winter.

Radio-tracking studies and literature searches have documented that the migratory distance of adults of various pond-breeding salamander species can range from hundreds of metres up to one km from the breeding pond into surrounding habitat (Semlitsch 1998, Faccio 2003, Bériault 2005). Based on those studies (none of which included the Small-mouthed Salamander) the adult Small-mouthed Salamander is presumed to travel only this limited distance (up to one km, but usually not more than 300 m) from the breeding site. This is calculated as the habitat area utilized by 90 percent of the adult population for each breeding location based on the movements of tracked individuals. The combination of water connected to suitable terrestrial habitat is therefore essential. Adult Small-mouthed Salamanders do cross roads (Bogart and Licht 2004) and the road itself would therefore probably not be a habitat barrier although heavy traffic could be.

These habitat needs are similar to those of other mole salamanders (Spotted Salamander (Ambystoma maculatum), Blue-spotted Salamander, Jefferson Salamander, and Eastern Tiger Salamander (Ambystoma tigrinum)). The Blue-spotted Salamander is more likely to be found above ground during the warmer months and the Eastern Tiger Salamander is less dependent on forested habitats than most other Ambystoma (Harding 1997, Jefferson Salamander Recovery Team 2009).

1.5 Limiting factors

Within its current range, the Small-mouthed Salamander is limited by the availability of shallow water bodies which hold water until mid-summer, the absence of fish (which eat all life stages of salamanders) in those water bodies and the presence of soft moist shaded soils with burrows. Given the current fragmentation of wooded and wetland habitat on Pelee Island and the salamander’s dispersal abilities, in Ontario the species is restricted to a few sites on the island. However it may occur in more locations there than where it has been found to date (R. Gould, pers. comm. 2013).

Climate change bringing warmer temperatures and drier conditions with less snow and less water in vernal pools could further shrink the number of suitable locations and the area of suitable habitat on Pelee Island.

1.6 Threats to survival and recovery

Threats to the Small-mouthed Salamander in Ontario are listed below.

Habitat alteration, loss and fragmentation

Because of the very limited distribution of the Small-mouthed Salamander in Ontario, any change in habitat (pollution, drainage, permanent drier conditions or development activities) could have serious impacts on the Ontario population. Two of the five breeding sites on Pelee Island have already been lost. One of these was drained, cleared and filled for development (A. Woodliffe, pers. comm. 2013), which follows the general history of land use on the island: clearing and draining for agriculture and development (J. Crowley, pers. comm. 2013). Two of the remaining three breeding sites are on protected lands but the third is privately-owned. However, drainage of both private and public lands on the island is an ongoing concern for island residents as most of the island is below the average lake level. Continued drainage without sufficient consideration for natural processes could threaten the scattered wetland areas (A. Woodliffe, pers. comm. 2013).

Removal of tree cover and rotting logs is a particular threat. Trees keep the ground moist by providing shade and maintain water levels in breeding areas by retarding evaporation. Rotting logs provide habitat for adult salamanders and their invertebrate prey. Such removals not only eliminate habitat but also fragment remaining natural areas, making it more difficult for adult salamanders to travel. Loss of tree canopy has been shown to stop egg deposition in a mole salamander species (Felix et al. 2010) and to cause adult Ambystoma salamanders to move out of the area (Semlitsch et al. 2008).

Invasive and introduced species

The ongoing encroachment of European Common Reed (Phragmites australis ssp. australis) into wetlands and riparian areas on Pelee Island could degrade wetland habitat and reduce the availability of suitable egg placement sites (R. Gould, pers. comm. 2013). Although the specific impacts on salamanders are unknown, an analysis by Greenberg and Green (2013) has shown that population decline in Fowler’s Toad (Anaxyrus fowleri) populations is associated with the spread of the European Common Reed. Uncontrolled growth of dense stands of Common Reed stems can effectively eliminate shallow, sparsely vegetated, aquatic areas which are needed by both Fowler’s Toad and Small-mouthed Salamander.

The loss of shade due to the death of ash trees caused by the Emerald Ash Borer (Agrilus planipennis), an invasive, non-native species, may change wetland conditions, making them less suitable for salamanders (A. Woodliffe, pers. comm. 2013).

An incidental human threat is the introduction of carnivorous fish, which are predators on all life stages of salamanders, to breeding ponds, which could eliminate salamander populations.

Climate change

If the Small-mouthed Salamander were unable to breed for a few years due to temporary low water levels, it is unlikely that significant population declines would result. However, if climatic changes (such as higher temperatures, less snow, lowered water table, less water in vernal pools) eliminate a breeding site, the population in that area would disappear. Bogart and Licht (2004) noted in their 2000 visit to Pelee Island that water levels had lowered at one of the breeding wetlands and that this could be related to a lower water level in Lake Erie. This could, however, have positive effects by reducing the possibilities of flooding and the invasion of fish from Lake Erie (J. Bogart, pers. comm. 2013).

Pollution

Salamanders have been shown to be particularly sensitive to various pollutants, which can kill outright but also induce sublethal affects in embryos, larvae and adults. Given the agricultural character of Pelee Island, agricultural pesticides are a particular threat as they can reduce survival and metamorphosis of Ambystoma larvae by killing zooplankton thereby reducing food resources (Metts et al. 2005). De-icing salt runoff from Pelee Island roads is another pollutant threat as experimental concentrations have been shown to cause mass loss in Ambystoma egg clutches (Karraker and Gibbs 2011). In addition to pollution and sometimes working synergistically with pollutants, increased ultraviolet radiation caused by reduction of ozone in the stratosphere is another widespread threat to amphibians in general leading to population declines (Blaustein et al. 2003).

Predation

The Small-mouthed Salamander has evolved several strategies to avoid predation: adults live under cover or underground most of the year; above-ground movements during the breeding season are nocturnal; and larvae are aquatic and have hiding and avoidance strategies. These characteristics help to protect them from predators, including humans. However, a new potential predator with unknown impacts is now present on Pelee Island: the Wild Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo), introduced in 2002 (R. Gould, pers. comm. 2013). Wild Turkeys scratch to find food and in so doing, can disturb cover habitat for adult salamanders while eating any salamanders uncovered.

Road mortality

Small-mouthed Salamanders travel overland every spring during the breeding season and every summer after transformation. On Pelee Island, as elsewhere, this means that they sometimes cross roads. Due to the low traffic levels on the island, it is thought that this is not currently a large threat to the species (R. Gould, pers. comm. 2013).

However, the potential remains for mass mortality caused by traffic and subsequent population decline. Gibbs and Shriver (2005) showed that even a small annual road mortality risk can lead to local population extirpation of a mole salamander species. Beebee (2013) concluded from a literature review that the long-term effects of road mortality on populations of amphibians are often severe.

Competition and hybridization

The threat of competition from unisexuals and the Blue-spotted Salamander was discussed by Bogart and Licht (2004) and examined by Brodman and Krouse (2007). It was concluded that competition is probably not a concern to the continued existence of the Small-mouthed Salamander. Although there is insufficient evidence to rule definitively on this, it is known that unisexuals require a pure male of either species to reproduce. Other details considered as part of this analysis include the following:

- the Small-mouthed Salamander is larger than the Blue-spotted Salamander;

- the Small-mouthed Salamander can produce more eggs than the Blue-spotted Salamander;

- the Small-mouthed Salamander can occupy a wider diversity of habitats than the Blue-spotted Salamander; and

- Small-mouthed Salamander larvae have strategies to avoid the larger unisexual larvae.

1.7 Knowledge gaps

The isolated location of the Small-mouthed Salamander on Pelee Island has protected the species from human disturbance but has also limited visitation by naturalists and biologists. There are no monitoring programs on the island for water levels, habitat or salamander numbers, and no frequent enforcement or surveillance presence in the nature reserves. Without regular observations, identification and assessment of threats has been limited. In particular there has been little or no work done on the impact of introducing Wild Turkey to the island (R. Gould, pers. comm. 2013), the effects of European Common Reed on salamander habitat, the amount of road mortality on Pelee Island, or the potential future impacts of climate change on Pelee Island wetlands and salamander habitat.

Little scientific work has been done recently on the Small-mouthed Salamander in general and none in Canada. The density of “pure” populations of Small-mouthed Salamander is unknown and it has not been possible to assess trends in hybridization and polyploidy due to the difficulties associated with identification in the field (Bogart and Licht 2004). There are no size estimates for the Small-mouthed Salamander population. This information would be needed before any population restoration or re- introduction could be considered (J. Bogart, pers. comm. 2013).

1.8 Recovery actions completed or underway

Various organizations have undertaken the acquisition and protection of land on Pelee Island in order to maintain species and habitat; Ontario Parks, Essex Region Conservation Authority, Ontario Nature and the Nature Conservancy of Canada are included. Each provides some level of infrequent visitation and surveillance. Ontario Nature has a local steward group that checks on the Stone Road site annually (J. Urquhart, pers. comm. 2013). No active management or regular monitoring programs are carried out on these nature reserves (Fish Point, Stone Road).

The Province of Ontario provides species and habitat protection for the Small-mouthed Salamander under the Endangered Species Act, 2007. Activities that may impact the species or its habitat are subject to provisions of the act and applicable regulations.

2.0 Recovery

2.1 Recovery goal

The recovery goal is to ensure that threats to populations and habitat are sufficiently managed to allow for long-term persistence and expansion of the Small-mouthed Salamander population within its Ontario range on Pelee Island.

2.2 Protection and recovery objectives

Table 1. Protection and recovery objectives

[converted to a list]

- Protect and maintain the quality and quantity of habitat on Pelee Island where the Small- mouthed Salamander occurs.

- Implement a monitoring program for salamander populations, habitats and threats on Pelee Island including surveys of suitable habitat.

- Promote and carry out research on Small-mouthed Salamander genetics, populations and threats.

- Investigate existing, former and potential Small-mouthed Salamander habitats on Pelee Island to determine if restoration, re-introduction or population interventions would be appropriate.

- Implement education, stewardship and communication programs for private landowners, residents and visitors on Pelee Island.

2.3 Approaches to recovery

Table 2. Approaches to recovery of the Small-mouthed Salamander in Ontario

| Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Ongoing | Protection | 1.1 Develop a habitat regulation or habitat description to define the area protected as habitat for Small-mouthed Salamander in Ontario. |

|

| Necessary | Ongoing | Protection, Management |

1.2 Engage landowners, residents and visitors to develop habitat management and protection programs, which might include:

|

|

| Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Necessary | Ongoing | Inventory, Monitoring and Assessment | 2.1 Carry out regular inventory, monitoring, surveying and sampling activities for populations, reproduction, water levels, habitat quality, new locations and threats including road mortality, climate change, and European Common Reed invasion. |

|

| Beneficial | Short-term | Inventory, Monitoring and Assessment | 2.2 Survey suitable habitats to find unknown populations and locations which could be used in population interventions. |

|

| Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beneficial | Short-term | Research | 3.1 Study the impact of Wild Turkey predation on salamanders in general, and on Small-mouthed Salamander in particular. |

|

| Beneficial | Long-term | Research | 3.2 Promote research on Small-mouthed Salamander genetics, hybridization, polyploidy and population structure. |

|

| Beneficial | Long-term | Research | 3.3 Investigate the impact of climate change on Small-mouthed Salamander populations. |

|

| Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beneficial | Long-term | Management | 4.1 Carry out investigations on existing, former and potential Small-mouthed Salamander habitats on Pelee Island in order to gather information on current conditions, human activities and land uses which would be needed to develop and implement programs for restoration or re- introduction, if appropriate. |

|

| Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beneficial | Long-term | Education and Outreach, Communications, Stewardship | 5.1 Develop and implement programs for residents, landowners and visitors to deal with land management, road mortality and disturbance to salamanders and habitat. |

|

2.4 Area for consideration in developing a habitat regulation

Under the ESA, a recovery strategy must include a recommendation to the Minister of Natural Resources and Forestry on the area that should be considered in developing a habitat regulation. A habitat regulation is a legal instrument that prescribes an area that will be protected as the habitat of the species. The recommendation provided below by the author will be one of many sources considered by the Minister when developing the habitat regulation for this species.

Breeding habitat

All permanent and seasonal wetland habitats where the Small-mouthed Salamander is known to breed should be included in a habitat regulation. This would include vernal pools, ponds, flooded quarries, swamps and marshes, which at present totals only three locations. Any new locations found or any locations where the salamander is re-introduced should be added to the area regulated.

Terrestrial habitat

The terrestrial component of Small-mouthed Salamander habitat consists of woodlands, upland forests, swamps, successional areas, meadows, old fields, agricultural fields and other vegetated areas that provide conditions required for foraging, seasonal migration, growth and hibernation. Terrestrial habitat includes all of the areas and features described above that extend radially 300 m from the edge of any breeding wetland. The 300 m distance is based on the findings of telemetry studies of other similar species (K. Bériault, pers. comm. 2013, as reported in Semlitsch 1998, Faccio 2003, Bériault 2005) and is calculated as the habitat area utilized by 90 percent of the adult population for each breeding location based on the movements of individuals tracked for three months. Terrestrial habitat that meets these requirements should be included within the habitat regulation, similar to that recommended for the Jefferson Salamander (Jefferson Salamander Recovery Team 2009).

Connecting corridors that provide continuous extensions of the terrestrial habitats listed above, between the edge of one wetland breeding location and another, can extend up to one kilometre, the maximum presumed travel distance of an adult Small-mouthed Salamander (based on studies of other similar salamander species, such as Bériault 2005). These contiguous corridors should also be included within the habitat regulation. Non-vegetated open areas such as cultivated fields should also be included if part of a dispersal corridor, as these areas are not known to be a barrier to Small-mouthed Salamander dispersal.

Glossary

- Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC):

- The committee established under section 14 of the Species at Risk Act that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Canada.

- Committee on the Status of Species at Risk in Ontario (COSSARO):

- The committee established under section 3 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Ontario.

- Conservation status rank:

- A rank assigned to a species or ecological community that primarily conveys the degree of rarity of the species or community at the global (G), national (N) or subnational (S) level. These ranks, termed G-rank, N-rank and S-rank, are not legal designations. The conservation status of a species or ecosystem is designated by a number from 1 to 5, preceded by the letter G, N or S reflecting the appropriate geographic scale of the assessment. The numbers mean the following:

1 = critically imperilled

2 = imperilled

3 = vulnerable

4 = apparently secure

5 = secure - Costal grooves:

- Indentations in the skin corresponding to the location of ribs along the sides of salamanders.

- Ecological Land Classification (ELC):

- A system of classifying and describing land-units based on vegetation.

- Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA):

- The provincial legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Ontario.

- Genome:

- A set of chromosomes containing the genetic material of an organism.

- Hybrid:

- An offspring of two individuals of different species.

- Metamorphosis:

- Change of physical form, structure or substance, such as the change from larva to adult.

- Polyploidy:

- The condition of having more than two sets of chromosomes (e.g. triploid – three sets of chromosomes, tetraploid – four sets of chromosomes, etc.).

- Species at Risk Act (SARA):

- The federal legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Canada. This act establishes Schedule 1 as the legal list of wildlife species at risk. Schedules 2 and 3 contain lists of species that at the time the Act came into force needed to be reassessed. After species on Schedule 2 and 3 are reassessed and found to be at risk, they undergo the SARA listing process to be included in Schedule 1.

- Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) List:

- The regulation made under section 7 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that provides the official status classification of species at risk in Ontario. This list was first published in 2004 as a policy and became a regulation in 2008.

- Sympatric:

- Occurring in the same area.

- Synergism:

- Cooperative action of discrete agents such that the total effect is greater than the sum of the effects taken independently.

References

Beebee, T.J.C. 2013. Effects of road mortality and mitigation measures on amphibian populations. Conservation Biology 27(4):657-668.

Bériault, Karine, pers. comm. 2013. Telephone conversation with S. Hamill. April 2013. Species at Risk Biologist, OMNR, Vineland, ON.

Bériault, K.R.D. 2005. Critical Habitat of Jefferson Salamanders in Ontario: An Examination through Radiotelemetry and Ecological Surveys. M.Sc. Thesis, University of Guelph, 69 pp.

Bi, K. and J.P. Bogart. 2010. Time and time again: unisexual salamanders (genus Ambystoma) are the oldest unisexual vertebrates. BMC Evolutionary Biology 10:238.

Blaustein, A.R., J.M. Romansic, J.M. Kiesecker, and A.C. Hatch. 2003. Ultraviolet radiation, toxic chemicals, and amphibian declines. Diversity and Distributions 9:123-140.

Bogart, James, pers. comm. 2013. Telephone conversation with S. Hamill. April 2013. Professor Emeritus, University of Guelph, Guelph, ON.

Bogart, J.P. and L.E. Licht. 1986. Reproduction and the origin of polyploids in hybrid salamanders of the genus Ambystoma. Canadian Journal of Genetics and Cytology 28: 605-617.

Bogart, J.P. and L.E. Licht. 1991. Status Report on the Small-mouthed Salamander Ambystoma texanum in Canada. Report for the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC). 19 pp.

Bogart, J.P. and L.E. Licht. 2004. Update COSEWIC Status Report on the Small- mouthed Salamander Ambystoma texanum in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa.

Bogart, J.P., L.E. Licht, M.J. Oldham, and S.J. Darbyshire. 1985. Electrophoretic identification of Ambystoma laterale and Ambystoma texanum as well as their diploid and triploid interspecific hybrids (Amphibia: Caudata) on Pelee Island, Ontario. Canadian Journal of Zoology 63: 340-347.

Bogart, J.P., L.A. Lowcock, C.W. Zeyl, and B.K. Mable. 1987. Genome constitution and reproductive biology of the Ambystoma hybrid salamanders on Kelleys Island in Lake Erie. Canadian Journal of Zoology 65: 2188-2201.

Brodman, R. and H.D. Krouse. 2007. How Blue-spotted and Small-mouthed Salamander larvae coexist with their unisexual counterparts. Herpetologica 63 (2):135-143.

Crowley, Joe, pers. comm. 2013. E-mail correspondence with S. Hamill. August 2013 Herpetology Species at Risk Specialist, OMNR, Peterborough, ON.

Faccio, S.D. 2003. Post breeding emigration and habitat use by Jefferson and Spotted salamanders in Vermont. Journal of Herpetology 37:479-489.

Felix, Z.I., Y. Wang, and C.J. Schweitzer. 2010. Effects of experimental canopy manipulation on amphibian egg deposition. Journal of Wildlife Management 74(3):496-503.

Gibbs, J.P. and W.G. Shriver. 2005. Can road mortality limit populations of pool breeding amphibians? Wetlands Ecology and Management 13:281-289.

Gould, Ron, pers. comm. 2013. Telephone conversation and e-mail correspondence with S. Hamill. April and August 2013. Zone Ecologist, OMNR, Aylmer, ON.

Government of Canada. 2012. Species Profile (Small-mouthed Salamander). Species at Risk Public Registry. Website: http://www.sararegistry.gc.ca/species/speciesDetails_e.cfm?sid=284 [accessed April 2013].

Greenberg, D.A. and D.M. Green. 2013. Effects of an invasive plant on population dynamics in toads. Conservation Biology 27(5):1049-1057.

Harding, J.H. 1997. Amphibians and Reptiles of the Great Lakes Region. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, 378 pp.

Hedges, S.B., J.P. Bogart, and L.M. Maxson. 1992. Ancestry of unisexual salamanders. Nature 356:708-710.

Jefferson Salamander Recovery Team. 2009. Draft Recovery Strategy for the Jefferson Salamander (Ambystoma jeffersonianum) in Ontario. Ontario Recovery Strategy Series. Prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Peterborough, Ontario. vi + 27pp.

Karraker, N.E. and J.P. Gibbs. 2011. Road deicing salt irreversibly disrupts osmoregulation of salamander egg clutches. Environmental Pollution 159:833-835.

King, R.B., M.J. Oldham, and W.F. Weller. 1997. Historic and current amphibian and reptile distributions in the island region of western Lake Erie. American Midland Naturalist 138:153-173.

MacCulloch, R.D. 2002. The ROM Field Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of Ontario. Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, ON.

Metts, B.S., W.A. Hopkins, and J.P. Nestor. 2005. Interaction of an insecticide with larval density in pond-breeding salamanders (Ambystoma). Freshwater Biology 50:685-696.

Petranka, J. 1998. Salamanders of the United States and Canada. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington and London, 587 pp.

Semlitsch, R.D. 1998. Biological delineation of terrestrial buffer zones for pond-breeding salamanders. Conservation Biology 12(5):1113-1119.

Semlitsch, R.D., C.A. Conner, D.J. Hocking, T.A.G. Rittenhouse, and E.B. Harper. 2008. Effects of timber harvesting on pond-breeding amphibian persistence: testing the evacuation hypothesis. Ecological Applications 18(2):283-289.

Urquhart, John, pers. comm. 2013. Telephone conversation with S. Hamill. April 2013. Conservation Science Manager, Ontario Nature, Toronto, ON.

USGS National Amphibian Atlas. 2012. Small-Mouthed Salamander (Ambystoma texanum). Version 2.2 USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Laurel, Maryland. www.pwrc.usgs.gov/naa [link inactive]

Wilbur, H.M. 1972. Competition, predation, and the structure of the Ambystoma – Rana sylvatica community. Ecology 53:3-21.

Woodliffe, P.A. 2013. E-mail correspondence with S. Hamill. August 2013. District Ecologist (retired), OMNR.