Turnip Mosaic Virus (TuMV) of rutabaga

Learn about disease symptoms, infection sources, spread, cultural and chemical control of turnip mosaic virus (TuMV) in turnip.

ISSN 1198-712X, Published May 1988

Introduction

Approximately 1,500 hectares of rutabaga are grown in Ontario, mainly in the southwestern counties of Huron and Middlesex. Production is based almost entirely on one cultivar, Laurentian, and a quality, purple-top cultivar resistant to turnip mosaic virus (TuMV) is currently not available.

Turnip mosaic virus has caused recurring crop losses throughout Ontario. Identified as a problem in the early 1950's, outbreaks of TuMV were particularly severe during the sixties in the Guelph and Bradford areas. In 1971, high levels of infection occurred in the major production areas in the southwest of the province. In recent years, this disease has caused major crop losses to rutabaga throughout Ontario, with the most severe losses occurring in Huron and Middlesex counties.

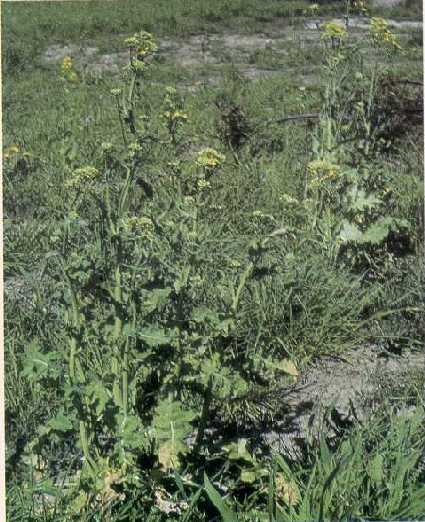

Disease Symptoms

The first indication of infection is often a premature yellowing and loss of older leaves of individual plants or patches of plants. In severe cases, the entire field will become infected and yellow all at once. Younger leaves produced after a plant becomes infected are stunted, wrinkled, and display a distinct mosaic pattern of yellow areas surrounded by normal green. Distinct symptoms on leaves of rutabaga develop approximately three weeks after plants become infected. The accelerated loss and replacement of leaves results in an elongated "goose necked" appearance of the roots. Infected rutabagas become stunted, and loss of leaves makes mechanical harvesting difficult. Roots of plants infected early in the season do not reach normal size.

Source of infection

The virus overwinters only in living plant tissue. In Ontario, important sources of infection early in the season include infected volunteer rutabagas and infected rutabagas dumped from storage in the spring, winter rapeseed fields and volunteer plants, and possibly a few species of wild plants. Even small amounts of overwintering virus can be important, and severe outbreaks of the disease often occur where volunteer rutabagas are growing in fields of wheat, barley, or other crops in close proximity to rutabaga fields. Strains of TuMV have been isolated in the spring from many wild plants, such as dame's violet, yellow rocket, garlic mustard, and watercress, but these strains generally do not infect rutabaga.

During the summer, the virus infects several cruciferous crops and some annual weeds. In addition to rutabaga and winter rapeseed, TuMV can be very devastating on chinese cabbage and other chinese vegetables, horseradish, and mustard crops.

Infection of winter rapeseed

In the fall, aphids move from rutabaga fields to winter rapeseed, and fields of winter rapeseed planted within two or three kilometers of rutabagas often become highly infected (80 to 100%) with TuMV. Leaves of rapeseed infected with the virus display a distinct yellow and green mottling (mosaic); infected plants become stunted and yellow prematurely; and seed pods become shrunken and twisted. Infection with TuMV decreases yield of winter rapeseed and may reduce winter hardiness.

Winter rapeseed is an important overwintering host for TuMV in southern Ontario, and rutabagas should be isolated from this crop as much as possible. Early plantings of rutabaga within about two kilometers of winter rapeseed are often infected earlier and more severely, while late-planted rutabagas within 5 to 10 kilometers of winter rapeseed are at risk because of the spread of TuMV directly from winter rapeseed or from previously infected early rutabagas and other summer hosts. Spring canola is rarely infected with TuMV, and it is not important in the spread of the disease to rutabaga.

Spread of TuMV to rutabaga

The virus is spread only by aphids. Water, soil, seed, machinery, and other insects do not spread the disease. Many species of aphids are able to spread (vector) the virus, and aphids that do not live on rutabaga are as important in the spread of the disease as aphids that colonize rutabaga plants. In Ontario, the corn leaf aphid and the green peach aphid have been shown to be the most important vectors of TuMV. Aphids require less than one minute of feeding to pick up the virus from infected plants, and an equally brief time to transfer the virus to a healthy plant. Because infection occurs so rapidly, insecticides are not effective for controlling the spread of TuMV. Large numbers of winged aphids move into the rutabaga crop daily, and several hours are required before they are killed by insecticides.

Effect of planting date on crop loss

A rapid increase in infection usually begins in early July when large numbers of winged aphids become active. Aphid flight continues from this time until the end of the growing season. Ideally, the main crop of rutabagas is planted during the final two weeks of June. Rutabagas planted at this time size during the cool fall weather, which improves the quality of the roots and prevents growth cracks and oversized roots. Losses from TuMV are greatly reduced, however, if the crop is sown no later than the third week of June and preferably prior to mid-June. Rutabagas planted after these dates are infected at a young age, and crop loss is often severe.

Applying additional fertilizer, particularly nitrogen, will not help rutabagas withstand damage from the disease, and may cause roots to break down rapidly in storage.

Cultural control of TuMV

Listed below is a summary of recommended cultural control measures:

- Rutabagas should not be plowed under in the fall, as this helps the roots survive the winter. Rutabagas left in the field after harvest should be disced and left on the surface to freeze. Volunteer plants that survive the winter should be destroyed early in the spring with herbicide sprays, removal by hand, or cultivation.

- Culls from storage should be dumped early and exposed to freezing weather. Culls surviving in piles can be killed with kerosene or diesel fuel. To prevent the spread of other rutabaga diseases, culls spread out on fields to freeze should not be placed on land that will be used to grow rutabagas for at least three years.

- Late-season fields located near earlier plantings often become highly infected, and they should be isolated as much as possible from earlier rutabagas. Whenever possible, isolate rutabagas from other cruciferous crops, particularly winter rapeseed.

- Whenever possible, plant rutabagas prior to mid-June, or at the latest by the end of the third week of June. Planting earlier prevents young highly susceptible plants from being exposed at the beginning of the infection period in early-July.

- Market virus-infected rutabagas as soon as possible. Storing infected roots may be unreliable, and it is best to use virus-free roots for long-term storage.

- Rutabagas under stress or grown improperly will be more severely affected by the disease.

Control of TuMV with weekly oil sprays

Weekly applications of oil (70 Superior Oil) are effective for controlling infection of rutabagas if used properly. Oil acts as a protectant, and prevents aphids from transmitting the virus by interfering with virus particles on aphid mouthparts. Proper application of oil requires the use of high spray volumes up to 1,100 litres per hectare (100 gal./acre) of a 1 to 2% oil solution. (1% solution equals one gallon oil plus 99 gallons water per acre). Apply oil using T-jet nozzles, preferably more than one per row. The use of drop nozzles will also improve coverage.

Weekly applications of oil should begin around the last week of June and continue at least until the end of July, preferably until the end of August. When plants are growing rapidly, a 5-day interval between sprays provides better coverage of new growth. Continuous coverage is very important, and plants must be protected as soon as they emerge. When plants are small, spray volumes can be reduced as long as leaves are thoroughly covered, but it is important that the amount of oil is reduced to maintain the proper oil concentration. Phytotoxic problems may occur if oil concentration exceeds recommended rates. Rutabagas may be damaged if oil is applied in full sunlight when temperatures exceed 25ºC, or when plants are visibly stressed. Do not apply oil in combination with other spray materials. If insecticides are required, apply them 24 hours before or after the oil.

Follow label recommendations. Refer to the current issue of OMAFRA Publication 363, Vegetable Production Recommendations for recommended insecticides.