2018 Pre-Election Report on Ontario’s Finances

The Pre-Election Report provides details on the three fiscal years (2018-19 to 2020-21) covered in the 2018 Budget’s medium-term fiscal plan, including estimated revenues and expenses, and other details of its fiscal planning process. The report must be reviewed by the Auditor General of Ontario, and helps ensure the public receives an independent assessment of the province’s finances in advance of the next general election.

Ministers’ Foreword

This 2018 Pre-Election Report on Ontario’s Finances (2018 Pre-Election Report) presents the fiscal plan for 2018–19 to 2020–21 fiscal years, consistent with the 2018 Budget presented on March 28, 2018.

Ontario’s economy has grown steadily in recent years, but we know that more must be done to encourage increased growth and create more jobs in an uncertain global economy. As we move forward, we must also ensure that the benefits from this growth are equally shared.

The 2018 Budget renews this government’s commitment to transforming and strengthening the vital public services the people of Ontario need and rely on. Our plan includes investments in new and innovative approaches to serving the diverse people of Ontario in all communities and sectors, including health care, education and social services.

Ontario’s fiscal policy is governed by principles that are based on cautious assumptions and recognize the need for flexibility to respond to changing circumstances. As we strive to create more opportunity and make care more affordable for people across Ontario during this period of rapid economic change, our fiscal plan considers the impact of today’s choices on different groups within the province and on future generations.

With this 2018 Pre-Election Report, we are providing information to ensure the people of Ontario receive an update of the Province’s finances, and are encouraging public discussion about the fiscal well-being of the province. Ontario was the first in Canada to introduce such a report, and today we continue to uphold our commitment to this important part of the democratic process.

The Honourable Eleanor McMahon

President of the Treasury Board

The Honourable Charles Sousa

Minister of Finance

Introduction

The purpose of the Fiscal Transparency and Accountability Act, 2004, is to provide greater transparency and accountability in the government’s fiscal planning and financial reporting. Under the Act, the government may release a pre-election report on Ontario’s finances in advance of a provincial election. The report must be reviewed by the Auditor General of Ontario.

This 2018 Pre-Election Report provides the people of Ontario with a clear understanding of the Province’s estimated future revenue and expense, and other details of its fiscal planning processes, before the provincial election scheduled for June 7, 2018. The report presents the three fiscal years (2018–19 to 2020–21) covered in the 2018 Budget’s Medium-Term Fiscal Plan.

This 2018 Pre-Election Report provides information on:

- The macroeconomic forecasts and assumptions that were used to prepare the fiscal plan set out in the 2018 Budget;

- An estimate of Ontario’s revenues and expenses, including estimates of the major components of revenues and expenses as set out in the plan;

- Details of the reserve included in the plan; and

- The ratio of provincial debt to Ontario’s gross domestic product (GDP).

The fiscal plan presented in the 2018 Ontario Budget — A Plan for Care and Opportunity, is the source of content in this report. For ease of reference, this report may point to the 2018 Budget for additional details.

The Planning Process

To understand the role of this report, it is important to first understand Ontario’s fiscal plan and how it is developed.

The 2018 Budget, which was released on March 28, 2018, covers a three-year planning horizon including the 2018–19 fiscal year, and is projected out for the subsequent two years. These three years make up the medium-term fiscal plan and provide a view of the Province’s fiscal direction. Ministries develop their input to the fiscal plan through the annual Program Review, Renewal and Transformation (PRRT) process. Launched in 2014, PRRT is the government’s ongoing fiscal planning and expenditure management approach. PRRT is designed around four key principles:

- Examining how government dollars are spent;

- Using evidence to inform better choices and improve outcomes;

- Looking across government to find the best way to deliver services; and

- Taking a multi-year approach to find opportunities to transform programs and achieve savings.

Through PRRT, the government is supporting evidence-based decision-making, and identifying transformational initiatives focused on modernizing services, finding savings and improving outcomes for the people of Ontario. By fostering collaboration across ministries, PRRT takes a coordinated approach to ensuring that programs are effective, efficient, sustainable and meeting the needs of Ontarians. This approach is improving how programs are delivered and identifying how resources can be redirected to help sustain the governments’ priorities, such as health care, education, child care and income security.

The PRRT process requires ministries to develop plans that are fiscally sound over the long term. Ministry PRRT plans, once reviewed and approved by the government’s Treasury Board and Management Board of Cabinet, form the basis for the expense estimates in the fiscal plan. The total expense outlook also includes interest on debt.

The government also estimates the revenue available to support expenses over the three years of the plan. Taxation revenue, in particular, depends largely on the outlook for the provincial economy. Transfers from the federal government are also an important component of Provincial revenue and are largely driven by funding formulas. The largest federal transfers are the Canada Health Transfer and Canada Social Transfer, which the province allocates based on its priorities. Estimates for other non-tax revenue and net income from Government Business Enterprises (GBEs) are based on economic and demographic factors, as well as government policy.

Once completed, the fiscal plan forms the Ontario budget, which reflects the government’s decisions about how expected resources will be allocated to achieve its priority outcomes.

The release of the budget is followed by the tabling of a detailed breakdown of ministry expense for the coming year, known as the Expenditure Estimates. The Expenditure Estimates constitute the government’s formal request to the legislature for approval of expenditures. The Estimates, once concurred by the legislature, support the passage of the Supply Act, which gives the government legal spending authority.

Prudence and Flexibility

The Fiscal Transparency and Accountability Act, 2004, sets out governing principles requiring Ontario’s fiscal policy to be based on cautious assumptions and to recognize the need for flexibility to respond to changing circumstances.

These principles underscore that the medium-term fiscal plan outlined in the budget is not static. It is based on government policy decisions and direction, as well as estimates built on reasonable assumptions at the time it is developed. After the budget is released, new priorities may emerge and economic performance may differ from what was forecast. Information and events that were not foreseen during planning may have positive or negative impacts on actual fiscal results.

The government has taken measures to ensure an appropriate level of prudence and flexibility is built into the medium-term fiscal plan, in accordance with the guiding principles governing fiscal policy set out in the Fiscal Transparency and Accountability Act, 2004. This plan provides a margin of caution to manage the uncertainty of future events that may adversely affect the government’s revenues and expenses. Moreover, prudent planning increases fiscal flexibility and improves the ability of government to meet its objectives.

A wide range of assumptions and planning tools help build prudence into Ontario’s medium-term fiscal plan. Here are some examples:

- Estimated revenue is based on an economic forecast using growth rates for real GDP that are set lower than the average of private-sector forecasts in each year. Starting out with the assumption that economic performance will be slightly lower than expected helps to provide a margin of caution in the revenue forecast.

- The plan includes contingency funds in each year to help mitigate risks that may otherwise have a negative impact on the fiscal results.

- Separate from the contingency funds, the fiscal plan also includes a reserve in each year to protect against unforeseen adverse changes in the Province’s revenue and expense outlook, including those resulting from changes in Ontario’s economic performance.

Additional Information

The medium-term fiscal plan presented in the 2018 Ontario Budget was based on the best information available on March 7, 2018. There are several opportunities for the government to update the public on the fiscal plan throughout the year. In the Ontario Quarterly Finances, updates to the fiscal outlook for the current year are provided, while the Ontario Economic Outlook and Fiscal Review provides a mid-year look at the state of the province’s finances and economy. The budget at the start of the next fiscal year includes a new medium-term fiscal plan. As well, the Fiscal Transparency and Accountability Act, 2004, requires a regular long-range assessment of Ontario’s fiscal environment and economy. Ontario’s Long-Term Report on the Economy, released in early 2017, highlighted the long–term challenges and opportunities that will affect the province over the next 20 years.

The complete financial results for the fiscal year are released in the Public Accounts. The Public Accounts include the Annual Report and Consolidated Financial Statements for the Province along with supplementary information contained in three volumes, and discuss the Province’s actual results against Budget, prior year and multi-year trends. The Public Accounts are audited and contain the report of the Auditor General on the government’s financial statements.

Readers can view these documents on https://www.ontario.ca

Statement of Ministry of Finance and Treasury Board Secretariat Responsibility

This 2018 Pre-Election Report on Ontario’s Finances has been prepared by the Ministry of Finance and Treasury Board Secretariat in compliance with the Fiscal Transparency and Accountability Act, 2004. This report presents the medium-term fiscal plan for 2018–19 to 2020–21, consistent with the 2018 Budget.

The Ministry of Finance and Treasury Board Secretariat are responsible for preparing the information contained in this report on behalf of the Government of Ontario. The ministries’ estimates of revenues and expenses have been developed consistent with the policy decisions of the government and assumptions on the projected performance of the Ontario economy, demands for government services and other key fiscal planning assumptions. Certain assumptions are based on anticipated actions, strategies and programs of the government that are consistent with the fiscal plan. The Ministry of Finance and Treasury Board Secretariat will assist the Office of the Auditor General of Ontario in its review of the report and the underlying assumptions.

In compliance with the requirements of the Fiscal Transparency and Accountability Act, 2004, this report includes the following information from the most recent fiscal plan:

- The macroeconomic forecasts and assumptions that were used to prepare the fiscal plan;

- An estimate of Ontario’s revenues and expenses, including estimates of the major components of revenues and expenses as set out in the plan;

- Details of the reserve described in subsection 5(4) of the Act; and

- Information about the ratio of provincial debt to Ontario’s gross domestic product.

The estimates are based on the best information available as of March 7, 2018. Information related to material events that occurred after March 7, 2018, will be shared with the Office of the Auditor General of Ontario to support its review of this report.

The Ministry of Finance and Treasury Board Secretariat do not provide assurance on the achievability of the prospective results because events and circumstances frequently do not occur as expected, and the achievement of prospective results is dependent on future policy decisions and actions of government as well as future economic conditions.

The financial estimates in this report have been prepared in accordance with accounting principles for governments issued by the Public Sector Accounting Board (PSAB) of the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada). The accounting policies are consistent with those used in preparing the annual consolidated financial statements of Ontario.

Scott Thompson

Deputy Minister,

Ministry of Finance

Helen Angus

Deputy Minister,

Treasury Board Secretariat/

Secretary of Treasury

Board and Management Board of Cabinet

Cindy Veinot, FCPA,

FCA, CMA, CPA (DE)

Assistant Deputy Minister and

Provincial Controller,

Treasury Board Secretariat

March 22, 2018

Overview of the Fiscal Plan

The fiscal plan set out in this report covers the 2018–19 fiscal year, which ends March 31, 2019, and the two subsequent years, 2019–20 and 2020–21. The estimates of revenue and expense for these three fiscal years are the same as those in the 2018 Ontario Budget. They were developed from the Province’s economic and revenue forecasts, the Program Review, Renewal and Transformation (PRRT) process, and other government policy decisions and direction. They are based on economic assumptions and government planning decisions made up to March 7, 2018.

The medium-term fiscal plan includes the estimated revenue, expense and resulting deficit forecast for each of the next three years. It also includes a reserve for each year. The government is projecting deficits of $6.7 billion in 2018–19, $6.6 billion in 2019–20, and $6.5 billion in 2020–21.

| Item |

2018–19 |

2019–20 |

2020–21 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Revenue |

152.5 |

157.6 |

163.8 |

|

Expense |

|||

|

Programs |

145.9 |

150.4 |

155.8 |

|

Interest on Debt |

12.5 |

13.1 |

13.8 |

|

Total Expense |

158.5 |

163.5 |

169.6 |

|

Surplus/(Deficit) Before Reserve |

(6.0) |

(5.9) |

(5.8) |

|

Reserve |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

|

Surplus/(Deficit) |

(6.7) |

(6.6) |

(6.5) |

Table 1.1 Footnotes:

Note: Numbers may not add due to rounding.

This table is based on Table 3.8 of the 2018 Budget.

Macroeconomic Forecast and Assumptions

The Ministry of Finance consults extensively with private-sector economists to ensure reasonable and accountable economic projections. As well, three economic experts reviewed the Ministry of Finance’s 2018 Budget economic assumptions and found them to be reasonable.

The Ministry of Finance economic planning assumptions are slightly below the average from private-sector forecasters for Ontario real GDP growth. Changes in private-sector forecasts since March 1, 2018, have not materially altered the forecast average, and therefore do not affect Ministry of Finance assumptions upon which the medium-term fiscal plan is based.

| Item |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018p |

2019p |

2020p |

2021p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Real GDP growth |

2.9 |

2.6 |

2.7e |

2.2 |

1.8 |

1.9 |

1.7 |

|

Nominal GDP growth |

5.0 |

4.3 |

4.4e |

4.1 |

3.9 |

4.0 |

3.9 |

|

Employment growth |

0.7 |

1.1 |

1.8 |

1.7 |

1.1 |

0.9 |

0.8 |

|

CPI inflation |

1.2 |

1.8 |

1.7 |

2.2 |

2.2 |

2.1 |

1.9 |

Table 2.1 Footnotes:

e = estimate.

p = Ontario Ministry of Finance planning projection.

Sources: Statistics Canada and Ontario Ministry of Finance.

This table is based on Table 3.2 of the 2018 Budget.

Global Economic Environment

The Ministry of Finance outlook for major external factors shaping Ontario’s economic prospects is also closely tied to private-sector forecasts. These factors include the world, United States and Canada economic outlook, interest rates, the Canadian dollar exchange rate and oil prices. Developing revenue estimates requires highly detailed economic forecasts that often go well beyond what is readily available from most private-sector forecasters. As such, the more detailed components of the outlook are based on a combination of private-sector forecasts and macro-econometric models. Professional judgment also plays a role, especially in interpreting model results, judging the reasonableness of private-sector forecasts, and incorporating the latest information.

Forecasts for key external factors are summarized in Table 3.

| Item |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018p |

2019p |

2020p |

2021p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

World Real GDP Growth |

3.4 |

3.2 |

3.7e |

3.9 |

3.9 |

3.7 |

3.8 |

|

U.S. Real GDP Growth |

2.9 |

1.5 |

2.3 |

2.8 |

2.4 |

2.1 |

2.0 |

|

Canada Real GDP Growth |

1.0 |

1.4 |

3.0 |

2.2 |

1.8 |

1.9 |

1.7 |

|

West Texas Intermediate |

49 |

43 |

51 |

59 |

59 |

59 |

60 |

|

Canadian Dollar (Cents US) |

78.3 |

75.5 |

77.0 |

80.1 |

80.9 |

81.2 |

81.2 |

|

Three–Month Treasury Bill Rate |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.7 |

1.4 |

2.2 |

2.7 |

2.7 |

|

10–Year Government Bond Rate |

1.5 |

1.3 |

1.8 |

2.4 |

3.0 |

3.5 |

3.5 |

Table 3.1 Footnotes:

e = estimate.

p = Ontario Ministry of Finance planning projection based on external sources.

Sources: IMF World Economic Outlook (October 2017 and January 2018), U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Blue Chip Economic Indicators (October 2017 and February 2018), Statistics Canada, U.S. Energy Information Administration, Bank of Canada, Ontario Ministry of Finance Survey of Forecasters (March 2018) and Ontario Ministry of Finance.

This table is based on Table 3.3 of the 2018 Budget.

Risks to Ontario’s Economic Outlook

The table below shows the typical range for the first-and second-year estimated impacts of changes in key external factors on Ontario real GDP growth, based on historical relationships. Impacts are shown in isolation of changes to other external factors. The combination of changing circumstances can also have a substantial bearing on the actual outcome.

| Item |

First Year |

Second Year |

|---|---|---|

|

Canadian Dollar Depreciates by |

0.1 to 0.7 |

0.2 to 0.8 |

|

Crude Oil Prices Decrease by |

0.1 to 0.3 |

0.1 to 0.3 |

|

U.S. Real GDP Growth Increases by |

0.2 to 0.6 |

0.3 to 0.7 |

|

Canadian Interest Rates Increase by |

(0.1) to (0.5) |

(0.2) to (0.6) |

Table 4.1 Footnotes:

Source: Ontario Ministry of Finance.

This table is based on Table 3.4 of the 2018 Budget.

The Sensitivity Analysis presented in Table 6 of this report outlines the estimated impact of a one percentage point change in GDP on revenue. More detailed information on the Ontario economic outlook, including additional assumptions applied in the revenue estimates, is provided in the 2018 Budget.

Details on Medium-Term Fiscal Plan

The government is projecting deficits of $6.7 billion in 2018–19, $6.6 billion in 2019–20, and $6.5 billion in 2020–21.

Over the medium term, revenue is forecast to increase from $152.5 billion in 2018–19 to $163.8 billion in 2020–21, while total expense is projected to increase from $158.5 billion to $169.6 billion over the same period.

Details on Medium-Term Revenue Outlook

Ontario’s revenues rely heavily on the level and pace of economic activity in the province, with growth expected to be roughly in line with nominal gross domestic product (GDP) growth. For example, taxes are collected on the incomes and spending of the people of Ontario, and on the profits generated by businesses operating in Ontario.

However, there are important qualifications to this general relationship. The impact of housing completions and resales on Harmonized Sales Tax (HST) and Land Transfer Tax (LTT) revenues is proportionately greater than their contribution to GDP. Growth in several tax revenue sources, such as volume-based gasoline and fuel taxes, is more closely aligned to real GDP. Similarly, some revenues, such as vehicle and driver registration fees, tend to more closely track growth in the driving-age population.

Growth in some revenue sources, such as the Corporations Tax and Mining Tax, can diverge significantly from economic growth in any given year due to the inherent volatility of business profits, as well as the use of tax provisions such as the option to carry losses forward or backward across different tax years.

Total revenue is projected to increase from $152.5 billion to $163.8 billion between 2018–19 and 2020–21, or at an average annual rate of 3.7 per cent. Revenue growth largely reflects the Ministry of Finance’s outlook for economic growth.

| Item |

2018–19 |

2019–20 |

2020–21 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Revenue |

|||

|

Personal Income Tax |

35.6 |

37.7 |

39.7 |

|

Sales Tax |

26.8 |

27.9 |

28.9 |

|

Corporations Tax |

15.1 |

15.6 |

16.0 |

|

Ontario Health Premium |

3.9 |

4.1 |

4.3 |

|

Education Property Tax |

6.1 |

6.1 |

6.2 |

|

All Other Taxes |

16.0 |

16.7 |

17.3 |

|

Total Taxation Revenue |

103.6 |

108.1 |

112.4 |

|

Government of Canada |

26.0 |

25.7 |

26.8 |

|

Income from Government Business Enterprises |

5.3 |

6.0 |

6.6 |

|

Other Non-Tax Revenue |

17.6 |

17.7 |

18.0 |

|

Total Revenue |

152.5 |

157.6 |

163.8 |

Table 5.1 Footnotes:

Note: Numbers may not add due to rounding.

This table is based on Table 3.12 of the 2018 Budget.

Taxation Revenue

Taxation Revenue estimates are based on the economic outlook and are largely developed using models. Model-based forecasting that captures the relationship between a revenue source and its main economic drivers, given the structure of the tax system, is generally accepted as a best practice.

Personal Income Tax (PIT) revenue is estimated based on the latest available tax return processing information from the Canada Revenue Agency for 2016 tax returns processed during 2017. Future increases in tax revenue over that base are projected using models, with the outlook for compensation of employees as a key economic driver. The PIT revenue projection also reflects the impact of tax measures. Tax measures include those announced in past budgets and those proposed in the 2018 Budget, as well as the impact of federal measures including those announced in the 2018 federal budget. Excluding the impacts of tax measures, the PIT revenue base is projected to grow at an average annual rate of 5.4 per cent over the forecast period. This compares with average annual growth of 4.4 per cent in compensation of employees over this period. PIT revenue tends to grow at a faster rate than incomes due to the progressive structure of the PIT system.

Key assumptions: Expected PIT depends largely on growth in compensation of employees and other relevant drivers such as unincorporated business income, capital gains income and Registered Retirement Saving Plan (RRSP) contribution deductions. PIT revenue growth is also affected by the changes to assumed distribution of income across income levels as well as tax planning behaviour of individuals in response to policy measures. For example, the federal government have reported that their PIT revenues decreased by $1.2 billion, or 0.8 per cent between 2015–16 and 2016–17, stating that this “largely [reflects] the impact of tax planning by high-income individuals to recognize income in the 2015 tax year before the new [federal] 33 per cent tax rate came into effect in 2016. This behaviour raised revenues in 2015–2016 but lowered them in 2016–2017.”

Risks related to key assumptions: Variances in tax return processing during 2018, both for 2017 and for revenues in respect of prior years, would affect the base upon which growth is applied in forecasting revenues. In addition, there are uncertainties associated with the assumptions about growth in compensation of employees, unincorporated business income, capital gains income and RRSP contribution deductions. PIT revenue can also be significantly impacted by an income distribution different from the one assumed over the forecast period.

Ontario Health Premium revenue forecast is based primarily on the projected growth in the compensation of employees. As a result, Ontario Health Premium revenue is projected to increase at an average annual rate of 4.8 per cent over the forecast period. This is estimated based on essentially the same process, assumptions and risks as those discussed under PIT revenue above.

Sales Tax revenue projection is based primarily on growth in consumer spending. The Sales Tax revenue projection also reflects the impact of tax measures. Tax measures of $0.2 billion in 2018–19 primarily reflect the impact of measures announced in past budgets and those proposed in the 2018 Budget, as well as those announced in the 2018 federal budget. Excluding the impacts of measures, the Sales Tax revenue base is projected to grow at an average annual rate of 3.9 per cent, reflecting average annual growth in nominal consumption of 4.1 per cent over this period.

Key assumptions: The HST forecast is based on the latest federal estimates of Ontario’s 2018 HST entitlements. For the years beyond 2018, the HST revenue forecast largely depends on the Ministry of Finance’s outlook for household consumption expenditures. The projection also incorporates the expected impact of all relevant tax measures announced to date by the Ontario government.

Risks related to key assumptions: Finalization of each year’s HST entitlement takes place over a period of five-and-a-half years after the end of the year due mostly to revisions to the size of the overall GST and HST pool and Ontario’s share. These revisions can be significant. In addition, the forecast of the main HST economic drivers, in particular, total household consumption expenditure, is subject to significant forecast risks. While total consumption expenditure is a relatively stable component of the economy, its large size means that each percentage point change has a significant impact on HST revenue.

Corporations Tax (CT) revenue is based on the annual growth in the net operating surplus of corporations. The CT revenue projection reflects the impact of tax measures. Tax measures include those announced in past federal and provincial budgets, the 2017 Ontario Economic Outlook and Fiscal Review and those proposed in the 2018 Budget. After accounting for tax measures, the CT revenue base grows at an average annual rate of 2.5 per cent over the forecast period. This is in line with the 3.2 per cent average annual growth in the net operating surplus of corporations.

Key assumptions: The estimate of 2017 CT revenue upon which growth is applied is subject to change pending 2017 tax return filing and processing activities later in 2018. The outlook for CT is also dependent on the economic outlook for net operating surplus of corporations.

Risks related to key assumptions: The CT revenue outlook is subject to a high degree of uncertainty. Assessments arising from the filing and processing of 2017 corporate tax returns can have a significant impact on the revenue outlook. As well, net operating surplus for corporations are quite sensitive to changes in business conditions. The CT revenue outcome can also be affected by the composition of profits in the economy, as corporations have varying ability to apply discretionary tax deductions and allowances.

Education Property Tax revenue is projected to increase at an average annual rate of 0.7 per cent over the forecast period. This is largely due to growth in the property assessment base resulting from new construction activities.

Key assumptions: The forecast includes the expected growth of the tax base through additions and changes to the assessment roll each year. It reflects recent growth trends for each property class, as well as the Ministry of Finance’s outlook for new housing and condominium completions. As assessment growth each year is only a small fraction of the total assessment base, the overall tax base tends to be rather stable. The projection also incorporates the expected impact of all relevant tax measures announced to date by the Ontario government.

Risks related to key assumptions: This revenue component has been relatively stable. Risks to the forecast are expected to be minimal.

Revenues from All Other Taxes are projected to increase at an average annual rate of 4.0 per cent over the forecast period. This includes revenues from the Employer Health Tax, Land Transfer Tax, Beer, Wine and Spirits Taxes and volume-based taxes such as the Gasoline Tax, Fuel Tax and Tobacco Tax. For some of the smaller components, the estimate is developed based on revenue trends in recent years.

Key assumptions: The estimated growth in Employer Health Tax revenue is based on the outlook for wages and salaries growth. Gasoline Tax revenue estimates are largely based on real disposable income growth and gasoline pump price projections. The outlook for Fuel Tax revenue depends on overall economic activities, measured by real GDP growth projections, and diesel fuel pump prices. Land Transfer Tax revenue is estimated based on the forecast for resale activities and prices. The outlook for Beer and Wine Tax is based on projected growth in real disposable income and prices. The outlook for Electricity Payments in Lieu of Tax (PILs) is based on the estimated financial performance of Ontario Power Generation Inc., Hydro One Inc., and municipal electricity utilities. The Tobacco Tax estimate assumes a continuing trend towards reduced smoking. The remaining items included in other taxation revenue, such as Preferred Share Dividend Tax, Mining Profits Tax and Estate Administration Tax, are estimated largely based on recent past experience.

Risks related to key assumptions: Variances in estimated revenue from these tax sources generally arise from variances in the key assumptions outlined above, most notably growth in wages and salaries, real GDP growth, gasoline pump prices, and housing resale volumes and prices.

Federal Transfer Payments

The forecast for Government of Canada transfers is based on existing federal–provincial funding arrangements. Revenues are projected to increase at an average annual rate of 1.5 per cent over the forecast period, largely reflecting projected increases in the Canada Health Transfer, Canada Social Transfer, and enhanced and extended funding for labour market programs, partially offset by significantly lower projections of Equalization payments in the medium term. The medium-term revenue outlook also includes revised estimates related to the federal government’s current commitments for infrastructure funding.

Key assumptions: The estimate of federal transfer payments is based on existing federal–provincial funding arrangements and commitments, including transfers anticipated to support provincial investments in infrastructure projects, labour market programs, and home care and mental health services. These estimates are also shaped by federal legislation, funding formulas and the data applied in determining provincial entitlements.

Risks related to key assumptions: Ontario’s share of the Canada Health Transfer (CHT) and the Canada Social Transfer (CST) depends on Ontario’s share of Canada-wide population. Since federal revenue is the outcome of federal government decisions and interjurisdictional negotiations, there is always the possibility of changes in federal legislation, agreements and funding formulas that would have an impact on Ontario revenue.

Income from Government Business Enterprises

The outlook for Income from Government Business Enterprises (GBEs) is based on Ministry of Finance estimates of net income for Hydro One Limited (Hydro One) and information provided by Ontario Power Generation Inc. (OPG), Liquor Control Board of Ontario (LCBO) and the Ontario Lottery and Gaming Corporation (OLG). Overall revenue from GBEs is projected to increase at an average annual rate of 11.6 per cent reflecting higher overall net income from business enterprises.

Key assumptions: The enterprises apply a broad range of assumptions in developing their estimates. For example, estimated net income from the OLG is affected by economic growth, exchange rates and competition. Net income estimated for the LCBO depends on consumer purchasing patterns and the current policy environment insofar as it affects product prices or operating costs. The OPG and Hydro One net income estimates are based on information provided by OPG and the Ministry of Finance respectively. Ministry of Finance estimates of net income for Hydro One are based on a review of actual financial performance, regulatory submissions and decisions, including allowed revenue requirement recovery and assumptions, such as projected costs.

Risks related to key assumptions: As indicated above, the financial performance of government enterprises, including the newly created Ontario Cannabis Retail Corporation (OCRC), can be affected by a wide range of complex and potentially inter-related economic, market, cost, regulatory and policy factors.

Other Non-Tax Revenue

The forecast for Other Non-Tax Revenue is based on projections provided by government ministries and provincial agencies. Between 2018–19 and 2020–21, Other Non-Tax revenues are projected to increase at an average annual rate of 1.3 per cent mainly reflecting higher revenue growth from fees, donations, and other miscellaneous revenues projected under the broader public sector (BPS). This overall increase is partially offset by lower revenue growth from other non-tax revenue sources, including Carbon Allowance Proceeds.

Key assumptions: Much of this estimated revenue is largely determined by government revenue policy, with economic and demographic factors also playing a role. Revenue from Vehicle and Driver Registration fees, for example, is largely determined by the fee structure put in place by the Province. Year-over-year increases in the number of vehicles and drivers, which are largely determined by demographic factors, also affect revenue. Based on a strong performance of the 2017–18 cap-and-trade program auctions, projections on Carbon Allowance Proceeds are assumed to be strong in the medium-term. Non-tax revenue may also be affected by one-time or limited-time events.

Risks related to key assumptions: The risks associated with the estimation of recurring non-tax revenue are generally minor, as these tend to be fairly stable from year to year. However, changes in government policy decision on fee structures and asset sales can affect revenues from Other Non-Tax Revenue sources. Similarly, the cap and trade program with Ontario’s recent linkage with California and Quebec is effectively an international market and therefore subject to typical market risks such as exchange rate fluctuation and change in demand for carbon allowances.

Risks to the Revenue Outlook

Ontario’s revenue outlook is based on reasonable assumptions about the pace of growth in Ontario’s economy. There are both positive and negative risks to the economic projections underlying the revenue forecast. Some of these risks are discussed in this section.

The following table highlights some of the key sensitivities and risks to the fiscal plan that could arise from unexpected changes in economic conditions. These estimates are only guidelines; actual results will vary depending on the composition and interaction of various factors. The risks are those that could have the most material impact on the largest revenue sources. A broader range of additional risks are not included because they are either less material or difficult to quantify. For example, the outlook for Government of Canada transfers is subject to changes in economic variables that affect federal funding, as well as changes by the federal government to the funding arrangements themselves.

|

Item/Key components |

2018–19 |

2018–19 |

|---|---|---|

|

Total Revenues |

||

|

Nominal GDP |

4.1 per cent growth in 2018 |

$1,010 million revenue change for each percentage point change in nominal GDP growth. Can vary significantly, depending on composition and source of changes in GDP growth. |

|

Total Taxation Revenues |

||

|

Revenue Base |

4.2 per cent growth in 2018–19 |

|

|

Nominal GDP |

4.1 per cent growth in 2018 |

$705 million revenue change for each percentage point change in nominal GDP growth. Can vary significantly, depending on composition and source of changes in GDP growth. |

|

Personal Income Tax (PIT) Revenues |

||

|

Revenue Base |

6.9 per cent growth in 2018–19 |

|

|

Compensation of Employees |

5.9 per cent growth in 2018 |

$349 million revenue change for each percentage point change in compensation of employees growth. |

|

2017 Tax-Year Assessments |

$30.3 billion |

$303 million revenue change for each percentage point change in 2017 PIT assessments. |

|

2016 Tax-Year and Prior Assessments |

$1.6 billion |

$16 million revenue change for each percentage point change in 2016 and prior–year PIT assessments. |

|

Sales Tax Revenues |

||

|

Revenue Base |

4.3 per cent growth in 2018–19 |

|

|

Nominal Household Consumption |

4.8 per cent growth in 2018 |

$203 million revenue change for each percentage point change in nominal household consumption growth. |

|

2016 Gross Revenue Pool |

$27.5 billion |

$275 million revenue change for each percentage point change in 2016 gross revenue pool. |

|

2017 Gross Revenue Pool |

$28.8 billion |

$288 million revenue change for each percentage point change in 2017 gross revenue pool. |

|

2018 Gross Revenue Pool |

$30.0 billion |

$300 million revenue change for each percentage point change in 2018 gross revenue pool. |

|

Corporations Tax Revenues |

||

|

Revenue Base |

1.0 per cent growth in 2018–19 |

|

|

2017 Tax Assessments |

$13.0 billion |

$130 million change in revenue for each percentage point change in 2017 Tax Assessments. |

|

2018 Ontario Corporate Taxable Income |

$145 billion |

$140 million change in revenue for each percentage point change in the federal estimate of 2018 Ontario Corporate Taxable Income. |

|

2019 Ontario Corporate Taxable Income |

$148.4 billion |

$48 million change in revenue for each percentage point change in 2019 Ontario Corporate Taxable Income. |

|

2018 Net Operating |

1.5 per cent growth in 2018 |

$99 million change in revenue for each percentage point change in 2018 net operating surplus growth. |

|

Employer Health Tax Revenues |

||

|

Revenue Base |

5.8 per cent growth in 2018–19 |

|

|

Compensation of employees |

5.9 per cent growth in 2018 |

$63 million revenue change for each percentage point change in compensation of employees growth. |

|

Ontario Health Premium (OHP) Revenues |

||

|

Revenue Base |

5.7 per cent growth in 2018–19 |

|

|

Compensation of Employees |

5.9 per cent growth in 2018 |

$27 million revenue change for each percentage point change in growth in compensation of employees. |

|

2017 Tax–Year Assessments |

$3.4 billion |

$34 million revenue change for each percentage point change in 2017 OHP assessments. |

|

Gasoline Tax Revenues |

||

|

Revenue Base |

0.9 per cent growth in 2018–19 |

|

|

Gasoline Pump Prices |

119.3 cents per litre in 2018 |

$3 million revenue decrease (increase) for each cent per litre increase (decrease) in gasoline pump prices. |

|

Fuel Tax Revenues |

||

|

Revenue Base |

2.1 per cent growth in 2018–19 |

|

|

Real GDP |

2.2 per cent growth in 2018 |

$11 million revenue change for each percentage point change in real GDP growth. |

|

Land Transfer Tax Revenues |

||

|

Revenue Base |

1.7 per cent increase in 2018–19 |

|

|

Housing Resales |

2.0 per cent increase in 2018–19 |

$31 million revenue change for each percentage point change in both the number and prices of housing resales. |

|

Resale Prices |

No growth in 2018–19 |

|

|

Canada Health Transfer |

||

|

Ontario Population Share |

38.7 per cent in 2018–19 |

$39 million revenue change for each tenth of a percentage point change in Ontario’s population share. |

|

Canada Social Transfer |

||

|

Ontario Population Share |

38.7 per cent in 2018–19 |

$14 million revenue change for each tenth of a percentage point change in Ontario’s population share. |

|

Carbon Allowance Proceeds |

||

|

Carbon Price ($ Canadian/tonne of carbon dioxide emissions) |

$19 in 2018–19 |

A one per cent increase (decrease) in the carbon price would result in a $20 million increase (decrease) in carbon allowance proceeds. |

Table 6.1 Footnotes:

This table is based on Table 3.16 of the 2018 Budget.

Details on Medium-Term Expense Outlook

The Province’s program expense outlook is projected to grow from $145.9 billion in 2018–19 to $155.8 billion in 2020–21. This reflects the government’s commitment to invest in priority areas such as health, education, child care and income security.

Expense estimates are based on the government’s planning process, which aims to ensure that government priorities are met. In some cases, these estimates are predicated on ministries continuing to move forward with the implementation of planned policy changes. Such changes may require administrative, regulatory or legislative instruments.

Targeted investments in key sectors aim to accelerate system transformation, maximize effectiveness and build longer-term sustainability. Action is underway to review and evaluate public programs to maximize efficiency, effectiveness and sustainability. This means ensuring the best outcomes are achieved through the most efficient means. It also means finding savings through program improvements and cost avoidance.

Expense estimates include investments in infrastructure. In line with the Public Sector Accounting Standards, the costs of highways, bridges, hospitals, college facilities, government buildings and other assets of the Province and the organizations consolidated in its financial statements are capitalized and amortized as expense over the assets’ expected useful service lives. Transfer payments for infrastructure provided to municipalities, universities and other broader public-sector entities not consolidated in the Province’s statements are recorded as an expense.

The estimated expense for many provincial programs depends on such factors as future utilization rates, enrolment and caseload growth rates, and labour costs. Actual expenses may differ from the amounts estimated in the fiscal plan, due to changes in any of these factors. The fiscal plan includes contingency funds to help mitigate expense risks. Contingency funds are $1.6 billion in 2018–19.

| Item |

2018–19 |

2019–20 |

2020–21 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Programs |

|||

|

Health Sector |

61.3 |

64.2 |

66.6 |

|

Education Sector |

29.1 |

30.1 |

31.5 |

|

Postsecondary and Training Sector |

11.8 |

12.0 |

12.0 |

|

Children’s and Social Services Sector |

17.9 |

18.7 |

19.8 |

|

Justice Sector |

5.0 |

5.0 |

5.0 |

|

Other Programs |

20.8 |

20.4 |

20.8 |

|

Total Programs |

145.9 |

150.4 |

155.8 |

|

Interest on Debt |

12.5 |

13.1 |

13.8 |

|

Total Expense |

158.5 |

163.5 |

169.6 |

Table 7.1 Footnotes:

Note: Numbers may not add due to rounding.

This table is based on Table 3.17 of the 2018 Budget.

Health Sector

Health sector expense is projected to grow from $61.3 billion in 2018–19 to $66.6 billion in 2020–21 — representing 4.3 per cent growth over the period — as a result of increased utilization of physician services, home care services, hospital services, addressing mental health and addictions, long term care home staffing and beds, responding to the opioid crisis, eliminating the annual deductible and co–payment for seniors under the Ontario Drug Benefit program and introducing a new drug and dental program for people who do not have coverage under an extended health plan.

The majority of the expense in the health sector is associated with providing funding for hospitals, including maintaining hospital operations and reducing wait times; funding for physician services; improving access to drugs; and enhancing services for long–term care, and home and community care.

Key assumptions: Estimates are based on assumptions about population growth and aging, demand for services, new technology, price inflation, and delivery of government priorities.

Risks related to key assumptions: Changes in expense in this sector can arise from inflation, new technologies and program demands (utilization) as well as sector compensation.

Hospitals: Hospital program expense for the Province is $18.8 billion in 2018–19, accounting for 30.6 per cent of total health sector expense.

A funding increase of 4.6 per cent to the hospital sector will assist in managing increased emergency department volumes and admissions, increased numbers of procedures for hips, knees, cataracts as well as additional lifesaving procedures including cardiac, neuro and transplant procedures.

Additional cost drivers: Ontario’s growing and aging population has created pressures on current health system capacity and increasing complexity of care. Demand for investment in major hospital projects continues to grow as a result of population growth and shifting demographics, aging hospital facilities and the need for modernized models of care.

Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP): Payments made for care and services provided by physicians and practitioners are $14.7 billion in 2018–19 representing 23.9 per cent of health sector spending.

Additional cost drivers: Other cost drivers affecting OHIP include price and changing health care needs, including number of physicians and volume of laboratory tests.

Home and Community Care Sector: Payments in the Home and Community Care sector are $6.1 billion for 2018–19 accounting for close to 10 per cent of total health sector expense.

Additional cost drivers: Ontario is investing in more home and community health care, not only to meet the demands of more seniors, but also to help more people receive the care they need at home when appropriate, rather than in costlier hospital or long–term care settings.

Long-Term Care Sector: Funding to operate over 78,000 long–term care beds for residents who cannot live independently and require 24/7 nursing care is estimated to be $4.3 billion in 2018–19, accounting for 7 per cent of total health sector expense.

Additional cost drivers: Increased acuity of care required for residents with complex medical issues and behaviours. This pressure is expected to grow along with Ontario’s aging population.

Ontario Public Drug Programs: Funding for the Ontario Public Drug Programs provided through the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care is $4.7 billion in 2018–19,accounting for 7.7 per cent of health sector expense.

Additional cost drivers: Growth for the Ontario Public Drug Programs is projected to increase by 5 per cent annually reflecting seniors’ annual population growth of 2 to 4 per cent, and demand for new and more expensive drugs including medications to treat cancer, rare diseases and hepatitis C (cost per claim growth assumed at 2 per cent per annum) and additional growth related to elimination of co-pay and deductible for all seniors.

OHIP+ is a new initiative; therefore 2018–19 will act as the program baseline. Note that this program is based on age-based eligibility; therefore, the recipient count is assumed to increase with population growth, which is at 2 per cent per annum.

Education Sector

Education sector expense is projected to grow from $29.1 billion in 2018–19 to $31.5 billion in 2020–21 — representing 4.1 per cent growth over the period. Investments in the sector include:

- Funding to support children with special needs, to enable school boards to hire additional professional support staff to eliminate waitlists for special education assessments.

- Investments to support positive mental health for all learners, to assist students with mental health needs or addictions.

- Investments to help 100,000 more children up to age four access licensed child care over five years, doubling the capacity for child care in Ontario for children in this age group.

- The implementation of free licensed care for preschool aged children, from the age of two-and-a-half until they are eligible to begin kindergarten.

Annual regulations made under the authority of the Education Act govern education funding in Ontario and set out the funding formula that allocates the Grants for Student Needs (GSN) to school boards for the school year. This funding formula largely reflects student enrolment. The GSN is funded by a combination of Education Property Tax revenue and direct transfers from the Province.

Key assumptions: Estimates are based on assumptions about child care, elementary, secondary and full-day kindergarten enrolment rates.

Risks related to key assumptions: Changes in expense in the education sector can arise from unexpected changes in child care, elementary, secondary and full-day kindergarten student enrolment, as well costs of labour agreements with teachers and education workers.

Postsecondary and Training Sector

Postsecondary and training sector expense is projected to grow from $11.8 billion in 2018–19 to $12.0 billion in 2020–21 — representing 0.9 per cent growth over the period. This modest expense growth builds on significant additional 2017–18 investments in the Ontario Student Assistance Program (OSAP) to support higher-than-forecast OSAP applications and awards, as well as investments such as innovative postsecondary programming, more responsive and flexible skills training, and enhancements to Ontario’s apprenticeship system. Funding is tied to factors such as:

- Student enrolment and growth, to provide a level of stability and predictability that allows colleges and universities to engage in multi-year planning.

- Performance funding based on key performance indicators (KPIs) such as graduation rates and employment rates following graduation.

- Special purpose grants, such as funding to support student access.

The sector also provides student financial aid support including scholarships and bursaries to ensure affordability. Starting in 2017–18, Ontario has consolidated most existing OSAP grants into a single new Ontario Student Grant. This grant is available for all types of students, including mature and married students.

Labour market employment and training services are provided to individuals, such as laid-off workers, and to employers through the government’s Employment Ontario system. Funding also supports apprenticeship, career and employment preparation and adult literacy and basic skills.

Key assumptions: Estimates are based on assumptions about enrolment rates of college and university students and uptake of student financial assistance as well as labour market and economic conditions.

Risks related to key assumptions: Changes in expense in this sector can arise from unexpected changes in student enrolment in postsecondary institutions, uptake of student financial assistance and economic conditions.

Children’s and Social Services Sector

Children’s and social services sector expense is projected to grow from $17.9 billion in 2018–19 to $19.8 billion in 2020–21 — representing 5.2 per cent growth over the period. This is mainly due to investments in reforming the social assistance system, including multi-year rate increases with a focus on increasing benefits and reducing complex rules for people, and investments to expand services for people living with developmental disabilities.

The majority of expense in this sector is associated with the legislated social assistance programs, which provide financial and employment assistance through Ontario Works and the Ontario Disability Support Program. The sector also delivers a range of programs and supports for adults with developmental disabilities, and the Ontario Child Benefit that is available to low-to moderate-income families with children under 18 years of age.

Key assumptions: Estimates for sector expense are based on assumptions about demographic outlook, labour market and economic conditions.

Risks related to key assumptions: Changes in expense in this sector can arise from changes in utilization rates as well as economic conditions.

Justice Sector

Justice sector expense is projected to remain stable at $5 billion between 2018–19 and 2020–21. The incremental investments in the sector reflect ongoing transformation of the justice system including corrections investments, implementation of the Safer Ontario Act, 2018, and bail/remand reform; the expansion of access to legal aid for low-income Ontarians; and ongoing repair, rehabilitation and construction of courts and correctional facilities.

Expense in this sector is associated with the provision of legislated front-line service delivery that ensures communities are protected by law enforcement and correctional systems are secure and efficient. It also ensures the prosecution of crime and administration of the courts upholds the law, victims and vulnerable persons are supported and other public safety measures such as coroners’ services and fire safety are delivered effectively.

Key assumptions: Estimates are based on the current forecasted cost of implementing sector-wide reforms and caseload demands on the system.

Risks related to key assumptions: Changes in expense in this sector can arise from changes in policy, implementation of corrections reform, revised construction timelines, changes in the complexity of cases, inmate counts, as well as sector compensation.

Other Programs

Other programs expense is projected to remain relatively stable at approximately $20.8 billion between 2018–19 and 2020–21. The changes over this period reflect the impact of adjustments associated with investments under federal infrastructure programs (e.g., Public Transit Infrastructure Fund and the Investment in Affordable Housing Program Extension), funding profile for the Climate Change Action Plan, and actuarial assessments of pension expense among other factors.

The other programs expense category includes programs and funding for the agricultural, municipal, financial services, manufacturing, energy, forestry, tourism, culture and transportation sectors, and for environmental protection and the day-to-day operation of government. It also includes government pension plans and benefits for retired employees, the Teachers’ Pension Plan and the Contingency Fund.

Key assumptions: The estimated expense for each of the above-noted sectors and activities is based on the best information regarding the government’s planned course of action as determined through the Program Review, Renewal and Transformation (PRRT) process, as well as changes in labour market and economic conditions.

Risks related to key assumptions: Changes in other programs expense may result from government decisions related to specific sectors as well as changes in labour market and economic conditions.

Interest on Debt

The total expense outlook includes interest on debt expense, which is projected to grow from $12.5 billion in 2018–19 to $13.8 billion in 2020–21. This increase is required to fund investments in capital assets and the deficit.

Key assumptions: For existing debt, interest expense is based on the terms of each debt issue. Interest expense of future debt projected to be issued in 2018–19 and 2019–20 is based on the Ministry of Finance forecast of Government of Canada interest rates provided in the 2018 Ontario Budget together with assumptions on the spread normally required by investors in the Province’s debt. For debt projected to be issued in 2020–21, interest expense is based on the historical 20-year average of interest rates.

Risks related to key assumptions: Forecasts of interest rates and spreads are subject to risks arising from unforeseen economic conditions or other events. Revisions to both the projected deficits over the budget outlook and investments in infrastructure may impact the amount of future debt required to be issued, and in turn, the interest on debt expense.

Risks to the Expense Outlook

The following table provides a summary of key expense risks and sensitivities that could result from unexpected changes in economic conditions and program demands. A change in these factors could affect total expense, causing variances in the overall fiscal forecast.

These sensitivities are illustrative and can vary, depending on the nature and composition of potential risks.

|

Program/Sector |

2018–19 Assumption |

2018–19 Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|

|

Health Sector |

Annual growth of 5.1 per cent |

One per cent change in health spending: $613 million |

|

Hospitals Sector Expense |

Annual growth of 5.9 per cent |

One per cent change in hospitals sector expense: $299 million |

|

Drug Programs |

Annual growth of 13.7 per cent |

One per cent change in program expenditure of drug programs: $47.4 million |

|

Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP) |

Annual growth of 3.0 per cent |

One per cent change in OHIP expense: $146.6 million |

|

Long-Term Care Homes |

78,229 long-term care home beds. Average Provincial annual operating cost per bed in a long–term care home: $54,730 |

One per cent change in number of beds: approximately $42.8 million |

|

Home Care |

Approximately 30 million hours of personal support services |

One per cent change in hours of personal support services: approximately $10.9 million |

|

Elementary and Secondary Schools |

Approximately 1,993,000 |

One per cent enrolment change: approximately $170 million |

|

Child Care |

Approximately 111,000 monthly average fee subsidies |

One per cent change in number of monthly average fee subsidies: approximately $12 million annually |

|

Ontario Student Assistance Program |

Approximately 420,000 Ontario Students Grants |

One per cent change in number of grants: approximately $17 million |

|

Ontario Works |

247,714 average annual caseload |

One per cent caseload change: $29 million |

|

Ontario Disability Support Program |

371,605 average annual caseload |

One per cent caseload change: $56 million |

|

Interest on Debt |

Average cost of 10-year borrowing in 2018–19 forecast to be approximately 3.4 per cent |

The impact of a 100 basis–point change in borrowing rates is forecast to be approximately $300 million |

Table 8.1 Footnotes:

This table is based on Table 3.18 of the 2018 Budget.

Details on the Reserve

As required by the Fiscal Transparency and Accountability Act, 2004, Ontario’s fiscal plan incorporates prudence in the form of a reserve to protect against unforeseen adverse changes in the Province’s revenue and expense outlook, including those resulting from changes in Ontario’s economic performance. The government can choose to offset the impact of such changes on the Province’s annual surplus or deficit by reducing the size of the reserve by an equivalent amount. If any portion of the reserve is not required by fiscal year-end, it is reflected as an improvement to the Province’s surplus or deficit position. The reserve has been set at $0.7 billion in 2018–19, 2019–20, and 2020–21.

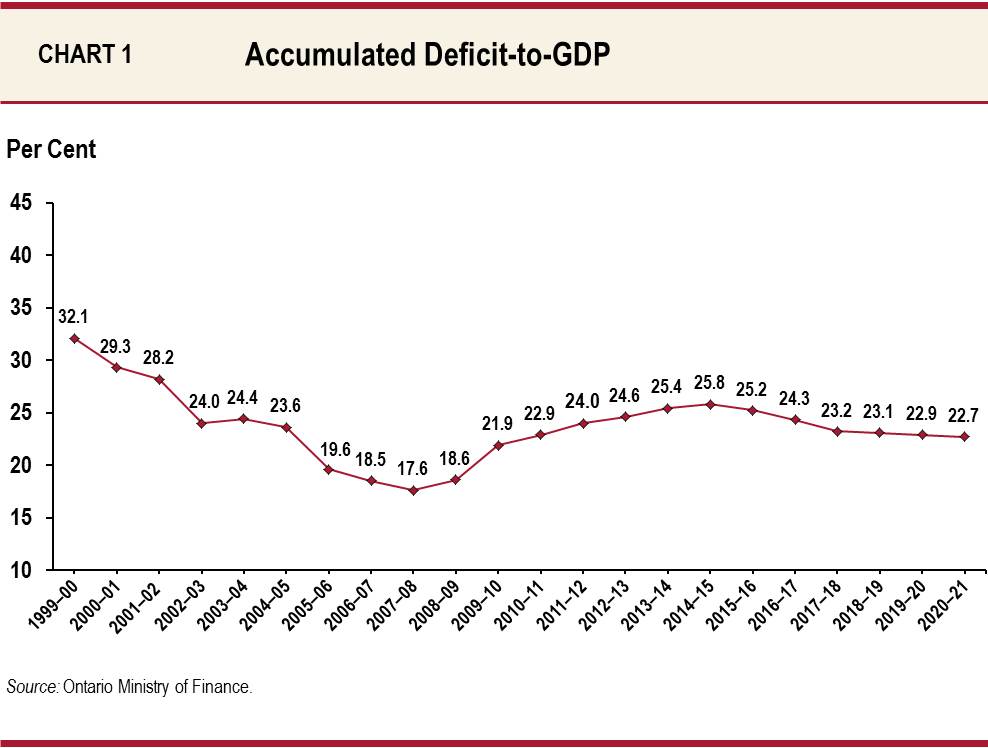

The Ratio of Provincial Debt to Ontario GDP

The Fiscal Transparency and Accountability Act, 2004, requires the fiscal plan to include information about the ratio of provincial debt to Ontario’s gross domestic product (GDP). Ratios of debt-to-GDP measure the relationship between a government’s obligations and its capacity to raise funds to meet them. Provincial debt is measured as the accumulated deficit for the purpose of the Act. Budgetary surpluses reduce the accumulated deficit, while deficits increase it. Accumulated deficit is projected to be $192.4 billion as of March 31, 2018.

Chart 1: Accumulated Deficit–to–GDP

Chart 1: Accumulated Deficit–to–GDP

Summary of Significant Accounting Policies and Contingent Liabilities

This section provides a summary of the basis of accounting, reporting entity and the significant accounting policies used in preparing the plan discussed in this report. Information on contingent liabilities is also provided. Please refer to the Public Accounts of Ontario 2016–17 Annual Report and Consolidated Financial Statements for further details.

Basis of Accounting

The Pre-Election Report is prepared on the same accounting basis as the 2016–17 Consolidated Financial Statements. The province applies accounting standards for governments recommended by the Public Sector Accounting Board (PSAB) of the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA Canada).

Reporting Entity

The estimated revenue and expenses reflect the expected activities of the Consolidated Revenue Fund combined with those organizations, which PSAB standards define as controlled by the Province, including public hospitals, school boards and colleges.

Government organizations controlled by the Province are consolidated if they meet one of the following criteria: i) their revenues, expenses, assets or liabilities are greater than $50 million; or ii) their outside sources of revenue, deficit or surplus are greater than $10 million.

Principles of Consolidation

Government Business Enterprises (GBEs) are recognized on a modified equity method, based on International Financial Reporting Standards, and taking into consideration the percentage of ownership owned by government during the year. Net income of the GBEs, including the newly formed Ontario Cannabis Retail Corporation, is shown as a separate item, Income from Government Business Enterprises.

Other government organizations controlled by the Province are consolidated on a line-by-line basis with the assets, liabilities, revenues and expenses based on the percentage of ownership the government held during the fiscal year.

Where appropriate, adjustments are made to present the accounts of these organizations on a basis consistent with the accounting policies of the Province, and to eliminate inter-organizational accounts and transactions.

Revenue

Tax revenues are recognized in the period in which the taxable event occurs and when authorized by legislation, estimated on taxpayer assessments, taxable income or other factors as appropriate.

Transfers from the Government of Canada are recognized as revenue in the period during which the transfer is authorized by the federal government and all eligibility criteria are met, except if the stipulations related to federal government funding create an obligation that meets the definition of a liability, in which case the revenue is recognized as the stipulations are met.

Revenue from the sale of emission allowances, which commenced in the 2017–18 fiscal year, is recognized when control of the allowances is transferred to the purchaser.

Other revenue is recognized in the fiscal year that the events giving rise to the revenue occurred and the revenue is earned.

Expense

Expenses are recognized in the fiscal year in which the events giving rise to the expenses occur and resources are consumed.

Transfer payments are recognized in the year in which the transfer is authorized and all eligibility criteria have been met by the recipient. Any transfers paid in advance are deemed to have met all eligibility criteria.

Interest on debt includes: i) interest on outstanding debt net of interest income on investments and loans; ii) amortization of foreign exchange gains or losses; iii) amortization of debt discounts, premiums and commissions; iv) amortization of deferred hedging gains and losses; and v) debt servicing costs and other costs.

Employee future benefits, such as pensions, other retirement benefits and entitlements upon termination, are recognized as expenses over the years in which the benefits are earned by employees. A valuation allowance is recorded to write down the Province’s share of net pension assets when the government assesses it is not entitled to fully benefit from the net pension asset.

The cost of tangible capital assets including buildings, transportation infrastructure, machinery, equipment, and information technology infrastructure owned by the Province and its consolidated organizations are capitalized and amortized over their estimated useful service lives on a straight-line basis.

New accounting standards on foreign currency translation and financial instruments are effective for the 2019–20 fiscal year, although the Public Sector Accounting Board is reviewing the effective date of these standards at its March 2018 meeting. The impact of these standards, if any, has not been reflected in the fiscal plan.

Rate–Regulated Accounting

In appropriate circumstances, rate-regulated entities establish regulated assets or liabilities and thereby defer the impact on the statement of operations of certain expenses or revenues because it is probable that the expenses or revenues will be collected or refunded to market participants through future billings. The accounting guidance applied is U.S. generally accepted accounting principles Topic 980, Regulated Operations. The entities applying rate-regulated accounting, reflected in this plan are both Government Business Enterprises recognized using the modified equity method (Hydro One Ltd. and Ontario Power Generation Inc.) and government organizations consolidated on a line-by-line basis (Independent Electricity System Operator).

Contingent Liabilities

In addition to the key demand sensitivities and economic risks to the fiscal plan, there are risks stemming from the government’s contingent liabilities. Whether these contingencies will result in actual liabilities for the Province is beyond the direct control of the government. Losses could result from legal settlements, defaults on projects, and loan and funding guarantees. Provisions for losses that are likely to occur and can be reasonably estimated are expensed and reported as liabilities in the Province’s financial statements. Any significant contingent liabilities related to the 2017–18 fiscal year will be disclosed as part of the 2017–2018 Annual Report and Consolidated Financial Statements, expected to be released later this year.

Chart descriptions

Chart 1: Accumulated Deficit–to–GDP

Accumulated deficit is projected to be $192.4 billion as of March 31, 2018, compared to a projection of $193.5 billion in the 2017 Budget.

|

Year |

Accumulated Deficit–to–GDP (%) |

|---|---|

|

1999–00 |

32.1 |

|

2000–01 |

29.3 |

|

2001–02 |

28.2 |

|

2002–03 |

24.0 |

|

2003–04 |

24.4 |

|

2004–05 |

23.6 |

|

2005–06 |

19.6 |

|

2006–07 |

18.5 |

|

2007–08 |

17.6 |

|

2008–09 |

18.6 |

|

2009–10 |

21.9 |

|

2010–11 |

22.9 |

|

2011–12 |

24.0 |

|

2012–13 |

24.6 |

|

2013–14 |

25.4 |

|

2014–15 |

25.8 |

|

2015–16 |

25.2 |

|

2016–17 |

24.3 |

|

2017–18 |

23.2 |

|

2018–19 |

23.1 |

|

2019–20 |

22.9 |

|

2020–21 |

22.7 |

Consolidated statement of estimated revenue, expense and reserve

April 25, 2018: The following consolidated statement of estimated revenue, expense and reserve compiles information disclosed in Tables 1, 5 and 7 of the 2018 Pre-Election Report on Ontario’s Finances, released on March 28, 2018. The information presented here is identical to that presented in those tables, and notes the table in which the information was originally included. Readers may find the compilation of this information into one table useful.

| Item |

2018–19 |

2019–20 |

2020–21 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Table 5, Page 13 |

|||

|

Revenue |

|||

|

Taxation Revenue: |

|||

|

Personal Income Tax |

35.6 |

37.7 |

39.7 |

|

Sales Tax |

26.8 |

27.9 |

28.9 |

|

Corporations Tax |

15.1 |

15.6 |

16.0 |

|

Ontario Health Premium |

3.9 |

4.1 |

4.3 |

|

Education Property Tax |

6.1 |

6.1 |

6.2 |

|

All Other Taxes |

16.0 |

16.7 |

17.3 |

|

Total Taxation Revenue |

103.6 |

108.1 |

112.4 |

|

Government of Canada |

26.0 |

25.7 |

26.8 |

|

Income from Government Business Enterprises |

5.3 |

6.0 |

6.6 |

|

Other Non-Tax Revenue |

17.6 |

17.7 |

18.0 |

|

Total Revenue |

152.5 |

157.6 |

163.8 |

|

Table 7, Page 22 |

|||

|

Expense |

|||

|

Program Expense: |

|||

|

Health Sector |

61.3 |

64.2 |

66.6 |

|

Education Sector |

29.1 |

30.1 |

31.5 |

|

Postsecondary and Training Sector |

11.8 |

12.0 |

12.0 |

|

Children’s and Social Services Sector |

17.9 |

18.7 |

19.8 |

|

Justice Sector |

5.0 |

5.0 |

5.0 |

|

Other Programs |

20.8 |

20.4 |

20.8 |

|

Total Program Expense |

145.9 |

150.4 |

155.8 |

|

Interest on Debt |

12.5 |

13.1 |

13.8 |

|

Total Expense |

158.5 |

163.5 |

169.6 |

|

Table 1, Page 8 |

|||

|

Reserve |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

|

Surplus/(Deficit) |

(6.7) |

(6.6) |

(6.5) |

See pages 32-34 of the Pre-Election Report for a summary of significant accounting policies and contingent liabilities

Note. Numbers may not add due to rounding.

Footnotes

- footnote[1] Back to paragraph The three experts are the Economic Analysis and Policy Program at the Rotman Institute for International Business, Rotman School of Management, University of Toronto; The Conference Board of Canada; and The Centre for Spatial Economics. The economic assumptions provided to the three forecasters is based on information available as of February 26, 2018.

- footnote[2] Back to paragraph Government of Canada interest rates.

- footnote[3] Back to paragraph Government of Canada, Public Accounts of Canada 2016–2017, Volume I, “Summary Report and Consolidated Financial Statement,” (2017).

- footnote[4] Back to paragraph Revenue Base is revenue excluding the impact of measures, adjustments for past Public Accounts estimate variances and other one–time factors.

- footnote[5] Back to paragraph Ontario 2017 Personal Income Tax and Corporations Tax are estimates because 2017 tax returns are yet to be assessed by the Canada Revenue Agency.

- footnote[6] Back to paragraph The Gross Revenue Pool is a federal Department of Finance estimate and excludes the impact of Ontario measures.

- footnote[7] Back to paragraph Excludes Teachers’ Pension Plan, which is included in Other Programs.

- footnote[8] Back to paragraph Hospital sector expense includes funding from the Ministry of Health and Long–Term Care and a number of Provincial programs from other ministries, as well as other third–party revenues.

- footnote[9] Back to paragraph Drug Programs includes startup funding for OHIP+.

- footnote[10] Back to paragraph Excludes Teachers’ Pension Plan

- footnote[11] Back to paragraph Includes Contingency Funds and Teachers’ Pension Plan