We've moved this content over from an older government website. We'll align this page with the ontario.ca style guide in future updates.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Vision for new quality of residential care branch/division within MCYS

Acts as integrating mechanism across all sectors to avoid silos, focus on quality of care, raise standards, encourage consistency, monitor continuum of care for individual young people, analyze aggregate data trends, and foster a culture of continuous quality improvement

Quality of residential care branch/division

Continuity of care unit

- Staffed by Reviewer positions

- Subsumes current Crown Ward Review Unit

- Monitors the continuum of care for all young people in care for 18 months or over

- Monitors all placements of young people transitioning from child welfare/children’s mental health into youth justice custodial settings

- Placement agencies notify Reviewers of placement changes

- Monitors placement changes

- Holds all data related to each young person (eg. serious occurrence reports; placement changes)

Data analytics & reporting unit

- High level aggregate data analysis

- Analyzes Serious Occurrence Report data

- Identifies trends

- Uses standardized data format

- Ensures data integrity

- Annual public reporting on progress of young persons in care

Quality inspectorate

- Replaces current licencing system

- New qualifications for position of quality inspector

- Includes assessment of quality indicators

- Includes assessment of agency concept statement

- Licensing function is subsumed in quality assessment

Advisory council

- Provide access to clinical expertise and lived experience (children and youth, families, caregivers including foster parents and front line workers).

Appendix 2: Concept statement template for service providers

Descriptive information about the organization

Name, address, contacts, programs and services offered:

Specific program to which this concept statement applies:

Mandate and vision of program:

Description of program:

Include #of clients, gender, ages, physical infrastructure, staffing ratio, #of staff, additional clinical resources, etc.

Youth profiles:

Define the profiles of young people who can best be served in this program; provide specific information about developmental and clinical profile, family constellation and need for participation, externalizing behaviours

Exclusions:

Describe who the program cannot serve well. List excluding factors (eg: fire setting, physical aggression, sexual offending)

Theoretical framework for service delivery:

What informs the design of this program? (eg: attachment theory, trauma-informed care, resilience, strength-based, narrative, etc.) Explain how this relates to the Youth profile the program seeks to serve.

Use of evidence-based practice:

List all evidence-based practices and clearinghouse references; explain how these relate to the youth profile the program seeks to serve

Use of best practices:

List all approaches and interventions that are considered best practices, and provide rationale for why these are considered best practices and references.

Youth voice and participation:

Describe all aspects of young people’s participation in the governance, design, operation and individual-level case planning in this program. Provide a list of measurable indicators for these initiatives.

Staff qualifications:

List all staff (FT/PT/Casual & One to One), their pre-service qualifications and their training and PD records for the past five years; explain how qualifications and training records relate to the client profiles the program seeks to serve and to the program and client-level objectives defined below.

Supervision:

Describe the supervision process for all front line staff; indicate the supervision model in use, and why this is the appropriate model in relation to the goals and objectives of the program and the types of young people served. Also include the qualifications and training of the supervisor.

Program objectives – program-level outputs and outcomes:

Describe what this program seeks to accomplish; what difference will it make in the lives of the young people; identify measurable indicators related to each program-level output and outcome.

Program objectives – client-level outputs and outcomes:

Describe what change is expected in clients; what areas of young person’s life will be impacted in what ways, and what indicators are used to measure this change.

Progress data from the past 12 months:

Listing each of the indicators identified for this program, provide data related to program-level and client-level outputs and outcomes.

Analysis of activity over the past 12 months:

Explain the data above in relation to what has worked and what has not worked. Provide clear explanations for any circumstances where the data does not indicate positive movement.

Children’s rights:

Describe how young people are informed of their rights and how rights reinforced on an ongoing basis. Please attach any material used in helping young people understand their rights.

Behaviour management/intervention:

Describe the approach to behavior management within the program. Include descriptions of point and level systems, token economies and frequently used consequences (withdrawal of privileges, early bed times, grounding).

Crisis management and physical intervention:

Describe the approach to crisis prevention/intervention. Include policies and practices related to the use of physical interventions, debriefing and restorative practices.

Community involvement:

Describe all community partnerships that are directly related to this program and provide a list of community involvements of every young person over the past 12 months. Provide a list of measurable indicators for these initiatives.

Unique identity:

Describe all initiatives related to support and special provisions in the context of gender identity, racial identity, cultural competence, vegetarian/ vegan lifestyles and other. Provide a list of measurable indicators for these initiatives.

Education:

Describes all initiatives and supports related to school-based performance and everyday life-based learning. Provide a list of measurable indicators for these initiatives.

Appendix 3 new worker training & refreshers

Description:

A mandatory two week training course required of all direct service staff hired to work in residential care settings such as group care and foster care support, including full time workers, part time workers, relief or casual workers and workers hired to perform one to one supervision under Special Rate Agreements. The New Worker training certificate must be completed prior to deployment in any residential care setting, and a biennial (every two years) two day refresher course must be completed thereafter.

Purpose:

To ensure that all workers involved in residential care provision are informed by and committed to working from an empathy-based perspective that is framed by the theoretical and practice elements of relational practice, life space intervention, ethical decision-making and child and youth participation, engagement and rights.

Structure:

The New Worker training course is to be delivered by the post-secondary education sector in partnership with the field. It is critical that the course be neither delivered nor owned by the field or any agency within residential care systems across sectors. Instead, the course must be delivered by the post-secondary education sector with a focus on child and youth care practice in particular, as the most relevant conceptual and practice elements envisioned for excellence in residential services are elements of the discipline of child and youth care practice.

Ontario’s post-secondary education sector offers 22 diploma and two degree programs in Child and Youth Care Practice, geographically spread across the province with excellent capacity to deliver such training, where applicable in partnership with institutional continuing education units (for example, the Chang School of Continuing Education at Ryerson University). It is envisioned that the training course is available to newly hired practitioners at least once per month at an institution at reasonable distance to the new employee.

The cost of such course should not exceed $500 per person, and residential service providers should be responsible for cost-sharing this cost at a minimum 50/50 split with prospective employees who do not yet have such certification. Certification is transferable across employers and sectors. Employers can create more competitive recruitment strategies by covering the full cost of the course.

Sample curriculum:

The ten-day curriculum is envisioned to include the following elements:

- Understanding the context of young people placed in residential care

- Empathy and the development of Self

- Relational practice – theory

- Relational practice – practice elements

- Life-space intervention

- Children’s rights and child and youth participation / engagement

- Unique cultural, identity and lifestyle contexts

- Ethical decision-making, the use of supervision, team work

- Crisis Intervention certification

Refresher training:

A two day training program every two years, with a curriculum that captures the core elements of the New Worker training but seeks to incorporate the practice experiences of workers in order to bring the concepts of the new worker training to life.

Appendix 4: Supervisor certification

Rationale:

The Panel strongly recommends the development of a supervisor certification program in order to ensure that individuals with responsibility to provide supervision are qualified to do so and able to provide such supervision meaningfully and directly related to life space practice settings. Supervision is a core component of effective child and youth care practice in residential settings. The supervision process should ensure at least four continuous dynamics:

- Workers are provided with clinical guidance in their practice with children and youth in the every day context of residential care;

- The residential setting is fundamentally oriented toward relational practices and the empowerment and participation of young people in their every day experiences;

- Practitioners are supported in their experiences of working with very vulnerable young people in such a way that their resilience in relation to compassion fatigue, vicarious trauma and burnout are mitigated;

- Practitioners have real and meaningful professional development and career planning goals that ensure on-going learning and skills development.

The current approaches to appointing individuals to supervisory positions are ad hoc in most cases and across sectors, with standards and required qualifications either absent or geared solely toward positive performance in front-line positions This is not adequate given the pivotal role of supervisor positions in residential services.

Description:

A supervisor certification process must be developed that ensures that anyone appointed to such a position is trained and has demonstrated competence in the following areas of practice:

- In-depth understanding of relational practices, including clinical, therapeutic and practice approaches;

- Capacity to support and coach front line practitioners in their capacity to deliver high quality services to young people and to maintain their relational engagement within the broader context of empathy;

- A thorough understanding of leadership in the context of collaborative team-based approaches to serving young people in residential services.

Structure:

The Panel envisions a multi-module certification program offered through recognized leaders in the field of child and youth care with clear capacity to offer training for supervisors at the highest possible level.. The minimum education level for the delivery agents of the certification program should be a university-based degree in child and youth care practice. The Panel furthermore recommends that existing supervisors be required to complete the certification process within the first year of its availability; newly hired or promoted supervisors must complete the certification prior to beginning work in formal supervisory positions in any context of residential service provision.

The specific curriculum of such program should be developed in partnership between the field and recognized leaders in the field of child and youth care practice. MCYS should provide leadership in ensuring that a small group of such individuals is constituted in order to proceed with the development of this process as soon as possible.

Appendix 5: Residential services review panel consultations

August 20th, 2015 – January 25th, 2016

Overview

The Panel consulted with:

- 264 Youth

- 18 Secure Treatment E.D.’s, Managers & Supervisors

- 25 Mental Health Treatment Agencies Managers & Directors

- 169 Frontline Staff

- 47 Facilities & Centres E.D.’s, Managers & Directors

- 38 Secure Custody E.D.’s, Managers & Supervisors

- 9 Open Custody E.D.’s, Managers & Directors

- 56 Foster Parents, Parents & Family Members

- 26 Associations/ Organizations/ Representatives E.D.’s, Managers & Executive

- 82 CAS Agencies E.D.’s, Managers Directors & Staff

- 123 MCYS Staff & Licencing Specialists

- 8 Regional and Corporate Directors

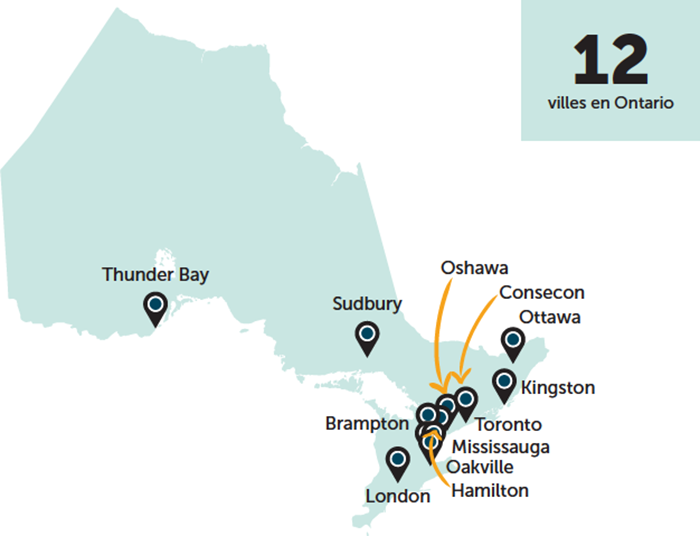

Cities

Across 12 cities in Ontario

Panel consultations - youth

264 Youth - 30 associations/organizations/representatives

| Associations/Organizations | Number of youth |

|---|---|

| Tungasuvvingat Inuit, Ottawa | 4 youth |

| Peel Children’s Centre, Mississauga | 4 youth |

| Ottawa Youth Engagement | 23 youth |

| J.J. Kelso, Thunder Bay | 4 youth (Lunch & 1-1 conversation) |

| Kairos Community Resource Centre, Thunder Bay | 2 youth |

| Thunder Bay Youth Engagement | 16 youth |

| LGBTQ2S Youth Engagement Toronto | 4 youth |

| Syl Apps, Oakville | 5 youth (1 Treatment / 4 Secure Custody) |

| Roy McMurtry Centre, Brampton | 7 youth |

| Child & Parent Resource Institute (CPRI), London | 8 youth |

| Genest Secure Facility, London | 1 youth |

| London Youth Engagement | 22 youth |

| Sudbury Youth Engagement | 29 youth |

| Toronto Youth Engagement | 37 youth |

| Sundance (St. Lawrence Youth Association), Kingston | 2 youth |

| Kingston Youth Engagement | 10 youth |

| Youth Amplifiers (PACY) | 11 youth amplifiers (two consultations) |

| YouthCan Consultation (OACAS) | 8 youth |

| PACY Round Table (Bayfield) | 45 youth |

| Murray McKinnon, Oshawa | 1 youth |

| Harold McNeil (SRR) Integration Centre, Oshawa | 2 youth |

| Enterphase, Oshawa | 6 youth |

| Child in Care by teleconference | 1 youth |

| Arrell Youth Centre (Banyan Community Services), Hamilton | 5 youth |

| New Mentality (CMHO) | 1 youth |

| The Village (Peel CAS) | 3 youth |

| Former Child in Care | 1 (Teleconference) |

Panel consultations - Frontline staff

169 frontline staff

| Associations/Organizations | frontline staff |

|---|---|

| Tungasuvvingat Inuit – Youth in Transition Worker – Ottawa | 1 staff |

| Peel Children’s Centre, Mississauga | 8 staff |

| Ottawa/Cornwall Region CAS/OPR’s | 8 staff |

| Dilico Anishinabek Family Care – Thunder Bay | 6 staff |

| CAS Thunder Bay | 25 staff |

| Thunder Bay Children’s Centre | 1 staff |

| Syl Apps, Oakville | 4 CYW |

| Roy McMurtry Centre, Brampton | 12 YSO & YSM |

| Child & Parent Resource Institute (CPRI), London | 8 staff |

| London CAS | 7 staff |

| Genest Secure Facility, London | 4 (Youth Service Officers, Two Teachers) |

| Sudbury Group Home | 3 staff |

| Sudbury CAS & Kina Gbezhgomi Child & Family Services, Sudbury | 4 staff |

| Peel CAS | 11 staff |

| Sundance (St. Lawrence Youth Association), Kingston | 1 staff |

| Frontenac CAS, Kingston | 21 staff |

| Murray McKinnon & Harold McNeil (SRR), Oshawa | 5 staff |

| Durham CAS, Oshawa | 13 staff |

| Toronto CAS | 7 (Children Service Workers, Foster Care Resources Workers & Resource Support Worker) |

| Toronto Catholic Children’s Aid Society | 8 (Placement Worker, Residence Worker, Short Term Child in Care worker, Child in Care Workers) |

| Hatts Off, Hamilton | 11 staff |

| Peel CAS – 1 staff | Diversity Manager |

| Nurse Practitioner from Secure Custody | 1 Nurse Practitioner |

Panel consultations - facilities & centres

47 E.D.’s, managers & directors

| Location | Number of managers & directors |

|---|---|

| Ottawa Inuit Children’s Centre | 4 (ED, Coordinator, Recreation Coordinator, Coordinator of Youth Carving & Art Program) |

| Tungasuvvingat Inuit, Ottawa | 1 (Coordinator) |

| Youth Services Bureau of Ottawa | 5 (ED, 3 Directors & 1 Assistant Director) |

| Dilico Anishinabek Family Care, Thunder Bay | 4 (2 -Assistant Director, 2 Program Managers) |

| Child & Parent Resource Institute (CPRI), London | 3 (Managers) |

| Sudbury Group Home Operators | 5 (Owners/Operators) |

| Kerry’s Place, Brampton and Mississauga Community Living | 7 (Directors and Service Managers) |

| Hatts Off, Hamilton | 11 (ED, Supervisors & Directors) |

| Stewart Homes | 1 (Teleconference) |

| Pioneer Youth Services | 1 (Teleconference) |

| Enterphase | 1 (Teleconference) |

| Community Living Toronto | 1 (Teleconference) |

| Carpe Diem Residential Therapeutic Treatment Homes for Children | 1 (Teleconference) |

| Good Shepherd Centre | 1 (Teleconference) |

| Batshaw Youth and Family Centres | 1 (Teleconference) |

Panel Consultations - Mental Health Treatment Agencies

25 E.D.’s, managers & directors

| Location | Number of managers & directors |

|---|---|

| Robert Smart Centre, Ottawa | 3 Rep (ED/Service Mgr & Coordinators) |

| Peel Children’s Centre | 4 (Manager, 2 Supervisors & 1 Clinical Director) |

| Thunder Bay Children’s Centre | 3 (ED and 2 Program Managers) |

| Syl Apps, Oakville | 15 (Directors, Coordinators, Managers, Psychiatrist, Psychologist, Clinical Director, Nurse, Recreation Therapist, Guidance & VP Program Services) |

Panel consultations - Open custody

9 E.D.’s, directors, managers & supervisors

| Location | Number of directors, managers & supervisors |

|---|---|

| Kairos Community Resource Centre, Thunder Bay | 1 (Manager) |

| Northern Youth Services, Sudbury | 4 (ED & Management Staff) |

| Murray McKinnon & Harold McNeil, Oshawa | 4 (ED & Directors & Supervisor of Harold McNeil) |

Panel consultations - secure custody

| Location | Number of managers & supervisors |

|---|---|

| J.J. Kelso, Thunder Bay | 2 (ED & Manager) |

| Syl Apps, Oakville | 15 (Directors, Coordinators, Managers, Psychiatrist, Psychologist, Clinical Director, Nurse, Recreation Therapist, Guidance & VP Program Services) |

| Roy McMurtry Youth Centre | 13 (YCA, DYCA, Managers, Coordinators, Nurse, Psychometerist, Social Worker, Chaplain) |

| Genest Secure Facility | 2 (Director & Assistant Director) |

| Sundance (St. Lawrence Youth Association), Kingston | 3 (Management) |

| Brookside Youth Centre | 1 (Teleconference) |

| Arrell Youth Centre (Banyan Community Services) | 2 (Program Director and CEO Banyan) |

Panel consultations - secure treatment

18 E.D’s, managers & directors

| Location | Number of managers & directors |

|---|---|

| Robert Smart Centre | 3 (ED/Service Manager & Coordinator) |

| Syl Apps, Oakville | 15 (Directors, Coordinators, Managers, Psychiatrist, Psychologist, Clinical Director, Nurse, Recreation Therapist, Guidance & VP Program Services) |

Panel consultations - children’s aid societies

82 E.D.’s, managers, supervisors & directors

| Location | Number of managers, supervisors & directors |

|---|---|

| CAS Ottawa | 3 (ED, Service Director & Manager of Services) |

| Family & Children’s Services of Renfrew County | 1 (Director of Services) |

| CAS Thunder Bay | 10 (Managers) |

| CAS London | 10 Staff (3 Service Directors, 7 Supervisors: Native Services, Resources, Recruitment, Kinship, Placement and Ongoing Services, Service Director of Resource & Permanency) |

| Sudbury CAS & Kina Gbezhgomi Child & Family Services, Sudbury | 8 (Managers) |

| Peel CAS | 4 (ED and 3 Managers) |

| Frontenac CAS, Kingston | 7 (Managers) |

| Durham CAS, Oshawa | 12 (ED, Directors, Supervisors: Family Care program, Kinship, Foster, Placement, Quality Assurance) |

| Toronto CAS | 8 (Directors and Managers) |

| Toronto Catholic Children’s Aid Society | 9 (Managers & Supervisors) |

CAS – Consultations by phone

| Location | Number of staff |

|---|---|

| Toronto Catholic Children’s Aid Society | 1 staff |

| Grey Bruce Children’s Aid Society | 1 staff |

| Waterloo Children’s Aid Society | 2 staff |

| Muskoka/Simcoe Children’s Aid Society | 1 staff |

| Windsor/Essex Children’s Aid Society | 2 staff |

| Hamilton Children’s Aid Society | 1 staff |

| Prescott (Vailor) | 4 staff |

| York Region Children’s Aid Society | 1 staff |

Panel consultations - Associations/Organizations

26 Associations/Organizations

| Location | Number of staff |

|---|---|

| Ontario Association of Residences Treating Youth (OARTY) – | 2 Meetings9 (August – 4 members and October – 5 members) |

| Centre of Excellence for Children and Youth Mental Health (OCE) | 1 (Executive Director) |

| Ontario Residential Care Association (ORCA) | 3 (1 by teleconference) |

| Ontario Association of Children’s Aid Societies (OACAS) | 5 (E.D., Analysts & Specialists) |

| Provincial Advocate (PACY) | 1 Group Consultation with Advocate, Youth & PACY Staff |

| Association of Native Agencies (ANO) | 4 Executive Directors of 4 agencies |

| LGBTQ2S Advisory Group – Group Consultation/Meeting | 1 Group Consultation with LGBTQ2S Youth & Agency Staff |

| CMHO/Kinark Forum – Toronto | Conference and Meeting with CMHO/Kinark Staff |

| Kinark | 4 Management |

| Ministry of Education | 1 Staff |

| Ministry of Health & Long Term Care | 3 Staff |

| Youth Justice Ministry Representatives | 1 meeting with YJ Staff |

| Children’s Mental Health Ontario (CMHO) | 4 (CMHO CEO, Kinark CEO, Windsor Hospital VP, Turning Point ED) |

| ANCFSAO | 5 (ED’s from 5 agencies) |

| Métis Nation of Ontario | 2 Staff |

| Ontario Native Women’s Association | 1 Staff |

| Ontario Federation of Indigenous Friendship Centres | 1 Staff |

| Ontario Association of Child & Youth Care | 3 (President & Board Members) |

| Youth Justice Ontario | 1 member |

| OACAS | 1 (OACAS Project Manager of “One Vision, One Voice”) |

| African Canadian Legal Clinic | 2 Staff (Policy & Research Lawyer) |

| Alberta Child & Youth Service | 1 Staff |

| University of Toronto | 1 Staff |

| Ontario Ministry of Training Colleges & Universities (TCU) | 3 Staff |

| Health Quality Ontario (HQO) | 1 (Director of Policy & Strategy) |

| Covenant House Toronto | 1 (Executive Director) |

Panel consultations - Foster Parents/Parents/Family

56 foster parents, parents & family

| Location | Number of forste parents, parents and family |

|---|---|

| Ottawa CAS hosted | 14 |

| Child & Parent Resource Institute (CPRI), London | 10 (9 Family & Parents & 1 CYW Worker/Advocate) |

| London CAS hosted | 5 Foster parents |

| Kingston CAS hosted | 12 Foster Parents |

| Foster Parents Association of Ontario | 3 Members/Foster Parents |

| Hatts Off | 8 Foster Parents |

| Foster Parents | 2 (Teleconference) |

| Adoptive Parent | 1 (Teleconference) |

| Family Member | 1 (Teleconference) |

Panel consultations - regional and corporate directors

8 regional and corporate directors

| Location | Regional and Corporate Directors |

|---|---|

| Regional and Corporate Directors | 8 |

Panel consultations - MCYS & licencing specialists

123 licencing specialist/program supervisors

| Location | Licencing Specialist/Program Supervisors |

|---|---|

| Licencing Specialists | 67 specialists |

| Program Supervisors | 29 (28 in person and 1 Teleconference) |

| Field Worker Application for Licencing | 3 staff |

| MCYS Staff | 2 staff |

| Crown Review Unit | 1 staff |

| CPIN Training | 2 staff |

| Centralized Access to Residential Services - C.A.R.S | 2 staff |

| Ministry of Education Early Learning Division | 1 staff |

| SOR Tool Demo | 1 staff |

| MCYS Corporate | 4 staff – Licencing |

| Central Region | 1 staff |

| Toronto Region | 1 staff |

| North Region | 1 staff |

| MCYS & MCSS North Region | 2 staff |

| East Region | 2 staff |

| Ministry of Community & Social Services | 2 staff |

| MCYS | 1 staff |

| ADMs | 4 ADMs |

Appendix 6: Bibliography

Addams, J. (1909). The spirit of youth and the city street. New York, NY: Macmillan.

Aichhorn, A. (1951). Wayward youth. London, UK: Imago.

Alexander, M.C. (2015). Measuring Experience of Care: Availability and Use of Satisfaction Surveys in Residential Intervention Settings for Children and Youth. Residential Treatment for Children and Youth, 32, 134-14.

Alkhenizan, A., & Shaw, C. (2012). The Attitudes of Health Care Professionals Towards Accreditation: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Journal of Family and Community Medicine, 19(2), 74-80.

Allen, K., Barrett, K., Blau, G., Brown, J., Ireys, H., Krissik, T., & Pires, S. (2011). Youth and family participation in the governance of residential treatment facilities. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 28, 311-326. Doi: 10.1080/0886571X.2011.615238

American Association of Children’s Residential Centers. (2009). Redefining residential: Performance indicators and outcomes. Residential Treatment for Children and Youth, 26(4), 241-245.

American Association of Children’s Residential Centers. (2009). Redefining Residential: Ensuring the Pre-Conditions for Transformation through Licensing, Regulation, Accreditation, and Standards, Residential Treatment for Children and Youth, 26, 257-240.

American Association of Children’s Residential Centres. (2014). Youth-guided treatment. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 31(2), 90-96. Doi: 10.1080/0886571X.2014.918424

American Association of Children’s Residential Centers. (2009). Redefining Residential: Becoming Family-Driven. Residential Treatment for Children and Youth, 26, 230-236.

American Association of Children’s Residential Centers. (2009). Redefining Residential: Family-Driven Care in Residential Treatment – Family Members Speak. Residential Treatment for Children and Youth, 26,252-256.

American Association of Children’s Residential Centers. (2014). Measuring Functional Outcomes. Residential Treatment for Children and Youth, 31,105-113.

Anglin, J. (2003). Pain, Normality, and the Struggle for Congruence: Reinterpreting Residential Care for Children and Youth. London, UK: Routledge.

Australian Government. (2015). Report on government services 2015: Child protection services (Chapter 15). Australian Government Productivity Commission. Retrieved from http://www.pc.gov.au/research/ongoing/report-on-government-services/2015/community-services/childprotection

Bay Consulting Group. (2006). The Bay Report. Retrieved from https://secure.oarty.net/opendoc.asp?docID=104

Behling, K.(2009). Redefining Residential: Performance Indicators and Outcomes. Retrieved from American Association of Children’s Residential Centers, 241-245.

Bell, E., Robinson, A., & See, C. (2013). Do Written Mandatory Accreditation Standards for Residential Care Positively Model Learning Organizations? Textual and Critical Discourse Analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 50, 1446-1458.

Bettelheim, B. (1974). Home for the heart. New York, NY: Knopf.

Bonnie, N., & Pon, G. (2015). Critical Well-Being in Child Welfare. A Journey towards Creating a New Social Contract for Black Communities. Retrieved from Ontario Association of Children’s Aid Societies as Printed Copies.

Brendtro, L. & Larson, S. (2004). The resilience code: Finding greatness in youth. Reclaiming Children & Youth, 12(4), 194-200.

Brendtro, L., & Mitchell, M. (2015). Deep brain learning: Evidence-based essentials in education, treatment, and youth development. Albion, Michigan: Starr Commonwealth.

British Columbia Ministry of Children and Family Development. (2015a). Fatalities of children in care by calendar year. Retrieved from http://www.mcf.gov.bc.ca/about_us/statistics.htm?WT.svl=Body

British Columbia Ministry of Children and Family Development. (2015b). Performance management report, volume 6. Retrieved from http://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/family-and-social-supports/services-supports-for-parentswith-young-children/reporting-monitoring/03-operational-performance-strategic-management/mcfd_pmr_ mar_2015.pdf

Brown, J., Ireys, F., Allen, K., Krissik, Tara., Barrett, K., Pires, Sheila., & Blau, G. (2011). Youth and Family Participation in the Governance of Residential Treatment Facilities., Residential Treatment for Children and Youth, 28,311-326.

Cairns, K. (2002). Attachment, Trauma and Resilience: Therapeutic Caring for Children. London, UK: British Association for Adoption and Fostering.

California Child Welfare Indicators Project. (2016). CCWIP reports. Retrieved from http://cssr.berkeley.edu/ucb_childwelfare/ReportDefault.aspx

Canadian Centre for Accreditation. (2015). CCA Accreditation for Youth Justice Organizations Standards Manual – Third Edition (Pilot). Retrieved from: https://www.canadiancentreforaccreditation.ca/sites/default/files/documents/ standards/cca_yj_standards_3rd_ed_pilot_nov_2015.pdf

Canadian Human Rights Tribunal. (2016). First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada et al. v. Attorney General of Canada (for the Minister of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada) file # T1340/7008

Program Templates. Retrieved from Catholic Children’s Aid Society of Toronto as Printed Copies.

Centralized Access to Residential Services (C.A.R.S). (2015). Guidelines, Policies, Procedures and Documentation. Retrieved from C.A.R.S as Printed Copies.

Centre for Excellence for looked after Children in Scotland. (2008). Moving Forward: Implementing the ‘Guidelines for the Alternative Care of Children’. Focus 14: Developing reliable and accountable licencing and inspection systems. Promising Practice 14.1: Programme for the supervision of children’s homes, Mexico.

Center for Excellence for looked after Children in Scotland. (2008). Moving Forward: Implementing the ‘Guidelines for the Alternative Care of Children’. Focus 14: Developing reliable and accountable licensing and inspection systems. Promising Practice 14.2: The RAF method for quality assurance in residential settings for children, Israel.

Centre for Excellence for looked after Children in Scotland, (2008). Moving Forward: Implementing the ‘Guidelines for the Alternative Care of Children’. Focus 14: Developing reliable and accountable licencing and inspection systems. Promising Practice 14.3: Minimum standards for residential and foster care in Namibia.

Chance, S., Dickson, D., Bennett, P.M., & Stone, S. (2010). Unlocking the Doors: How Fundamental Changes in Residential Care Can Improve the Ways We Help Children and Families. Residential Treatment for Children and Youth, 27,127-148.

Child Fund Australia. (2012). The role of child and youth participation in development effectiveness. A literature review, 1-25. Retrieved from http://www.unicef.org/adolescence/cypguide/files/Role_of_Child_and_Youth_Participation_ in_Development_Effectiveness.pdf

Children’s Aid Society of London. (2015). Southwest Region OPR Shared Services Orientation Package, Service Contract and Position Description. Retrieved from Children’s Aid Society of London as Printed Copies.

Children’s Aid Society of Ottawa. (2013). Annual Report. Retrieved from Children’s Aid Society of Ottawa as Printed Copies.

Children’s Aid Society of the Districts of Sudbury and Manitoulin. (2015). Community Mobilization Sudbury, Rapid Mobilization Table Progress Report Year 1 and Process and Protocols. Retrieved from Children’s Aid Society of Districts of Sudbury and Manitoulin as Printed Copies.

Children’s Aid Society of Toronto. (2015). Addressing Disproportionality, Disparity and Discrimination in Child Welfare. Data on Services Provided to Black African Caribbean Canadian Families and Children. Retrieved from: http://www.torontocas.ca/app/Uploads/documents/baccc-final-website-posting.pdf

Children’s Centre Thunder Bay. (2015). Annual report, Orientation Package and Documentation. Retrieved from Children’s Centre Thunder Bay as Printed Copies.

Children’s Mental Health Ontario. (2015). Implementing a Future Residential Treatment System for Children and Youth with Complex Mental Health Needs. (Draft).

Children’s Mental Health Ontario. (2015). Envisioning a Future Residential System of Care. A Summary of Key Feedback and Suggestions for System Improvement from Stakeholders across Ontario. Retrieved from http://www.kidsmentalhealth.ca/useruploads/images/Residential%20Symposium/CMHO_Environmental_Scan_ Residential.pdf

Coll, K., Sass, M., Freeman, B., Thobro, P., & Hauser, N. (2013). Treatment Outcomes Different Between Youth Offenders From a Rural Joint Commission Accredited Residential Treatment Center and a Rural Non-Accredited Center. Residential Treatment for Children and Youth, 30, 227-237.

Community Living Ontario. (2015). Recommendations resulting for Guy Mitchell Inquest. Retrieved from Community Living Ontario as Printed Copies.

Community Living Ontario. (2011). Peel Regional Respite Planning Group Summary. Retrieved from Community Living Ontario as Printed Copies.

Community Living Ontario. (2011). Services and Supports to Promote the Social Inclusion of Persons with Developmental Disabilities Act, 2008. Ontario Regulation 299/10. Quality Assurance Measures. Retrieved from https://www.ontario.ca/laws/regulation/100299

Courtney, M.E., Dworsky, A., Brown, A., Cary, C., Love, K., & Vorhies, V. (2011). Midwest Evaluation of the Adult Functioning of Former Foster Youth: Outcomes at age 26. Chicago, OH: Chapin Hall.

Cozens, W.R. (1996). Outcome Measurement: Who Ordered It, Anyway? Residential Treatment for Children and Youth,14(2) 45-59

Dilico Anishinabek Family Care. (2015). Guidelines, Policies, Procedures and Documentation. Retrieved from Dilico Anishinabek Family Care as Printed Copies.

Ellis, J., & Howe, A. (2010). The role of Sanctions in Australia’s Residential Aged Quality Assurance System. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 22 (6)452-460.

Enterphase Child and Family Services. (2013). 2013-2014 Residential Annual Report. Retrieved from Enterphase Child and Family Services as Printed Copies.

Enterphase Child and Family Services. (2015). Logic Model and Orientation Handbook. Retrieved from Enterphase Child and Family Services as Printed Copies.

Fallon, B., Van Wert, M., Trocmé, N., MacLaurin, B., Sinha, V., Lefebvre, R., Allan, K., Black, T., Lee, B., Rha, W., Smith, C., & Goel, S. (2015). Ontario Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect-2013 (OIS-2013). Toronto, ON: Child Welfare Research Portal

Fewster, G. (2014). Be gone, dull care. In K. Gharabaghi, H. Skott-Myhre, & M. Krueger (Eds.), With children and youth: Emerging theories and practices in child and youth care work (pp. 189-206). Waterloo, CAN: WLU Press

Finlay, J., & Scully, B. (2016). Cross Over Kids Project. Retrieved from http://www.provincialadvocate.on.ca/documents/en/CrossoverKids2-draft.pdf

Fleishman, R. (2002). The RAF method for regulation, assessment, follow-up and continuous improvement of quality of care: conceptual framework. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance and Incorporating Leadership in Health Services, 15(6-7), 311-23

Fleishman, R., Walk, D., Mizrahi, G., Bar-Giora, M., & Yuz, F. (1996). Licensing, Quality of Care and the Surveillance Process. International Journal of Health Quality Assurance, 9(7) , 39-45.

Flores, C., Bostrom, A., & Newcomer, R. (2009). Inspection Visits in Residential Care Facilities for the Elderly. The Effects of a Policy Change in California. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 28 (6), 539-559.

Flynn, R.; Dudding, P; & Barber, J. (Eds.) (2006). Promoting resilience in child welfare. Ottawa, CAN: University of Ottawa Press.

Foster Parents Society of Ontario. (2015). Strengthening Family Based Care Brief – A Foster Parents Society of Ontario Initiative – Prepared for the First Annual Winter Caregivers Forum. Retrieved from http://fosterparentssociety.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/BestPracticesBrief-Jan-29-2014.pdf

Foster Parents Society of Ontario. (2015). Foster Care Licencing Fieldworker User Guide. Retrieved from Foster Parents Society of Ontario as Printed Copies.

Garfat, T. (2008). The inter-personal in-between: An exploration of relational child and youth care practice. In G. Bellefuille & R. Ricks (Eds.), Standing on the precipice: Inquiry into the creative potential of child and youth care practice (pp. 7-34). Edmonton, CAN: MacEwan Press.

Gharabaghi, K. (2009). Private Service, Public Rights: The Private Children’s Residential Group Care Sector in Ontario, Canada. Residential Treatment for Children and Youth, 26(3), 161-180. doi: 10.1080/08865710903130228

Gharabaghi, K. (2010). In-Service Training and Professional Development in Residential Child and Youth Care Settings: A Three Sector Comparison in Ontario. Residential Treatment for Children and Youth, 27(2), 92-114. doi: 10.1080/08865711003712550

Gharabaghi, K., & Stuart, C. (2013). Right here, right now: Life-space intervention with children and youth. Toronto, ON: Pearson.

Goodman, D., Anderson, A., Cheung, C. (2008). The Future of Foster Care: Current Models, evidence based practices, future needs. Retrieved from http://www.childwelfareinstitute.torontocas.ca/app/Uploads/Resources/17_file.pdf

Greenfield, D., Braithwaite, J., (2008). Health Sector Accreditation Research: A Systematic Review. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 20 (1), 172-180.

Greenfield, D., Hinchcliff, R., Pawsey, M., Westbrook, J., & Braithwaite, J. (2013). The Public Disclosure of Accreditation Information in Australia; Stakeholder Perceptions of Opportunities and Challenges. Health Policy, 113, 151-159

Harold McNeill House Supportive Reintegration Residence. (2015). Youth Welcome Package, Education and Program Logic Model. Retrieved from Harold McNeill House as Printed Copies.

Hatts Off Inc. (2015). Guidelines, Policies, Procedures and Documentation. Retrieved from Hatts Off Inc. as Printed Copies.

Hodge-Williams, J., Doub, N., & Busky, R. (1995). Total Quality Management (TQM) in the Non-Profit Setting: The Woodbourne Experience. Residential Treatment for Children and Youth, 12(3) 19-30

Holden, M. (2009). Children and Residential Experiences: Creating Conditions for Change. Washington, DC: Children and Family Press

Jones, A., Sinha, V., Trocmé, N. (2015). Children and Youth in Out-of-Home Care in the Canadian Provinces. Retrieved from http://cwrp.ca/sites/default/files/publications/en/167e.pdf

Kapp, S., Hahn, S.A., & Rand, A. (2011). Building a Performance Information System for Statewide Residential Treatment services. Residential Treatment for Children and Youth. 28,39-54.

Kerry’s Place Autism Services. (2014). Community Services Needs Analysis Summary. Retrieved from Kerry’s Place Autism Service as Print Copies.

Kinark Child and Family Services. (2015). Strengthening Children’s Mental Health Residential Treatment through Evidence and Experience. Retrieved from http://www.kinark.on.ca/pdf/Strengthening%20 Children%E2%80%99s%20Mental%20Health%20Residential%20Treatment%20Through%20Evidence%20and%20 Experience.pdf

Knorth, E., Harder, A., Zandberg, T., & Kendrick, A. (2008). Under one roof: A review and selective meta-analysis on the outcomes of residential child and youth care. Children and Youth Services Review, 30, 123-140. Retrieved from http://rsw.sagepub.com/content/21/2/177.refs

Korczack, J. [1925] (1992). When I am little again and the child’s right to respect. New York, NY: University Press of America.

Kozlowski, A., Sinha, V., & Richard, K. (2012). First Nations Child Welfare in Ontario CWRP Information Sheet #100E. Montreal, QC: McGill University, Centre for Research on Children and Families.

Leaver, M. (2000). Residential Aged Care – Accreditation and Infection Control. Collegian, Vol 7, No 1.

Léveillé, S., Trocmé N., Brown, I., Chamberland, C. (2011). Research-Community Partnerships in Child Welfare. Retrieved from: http://cwrp.ca/sites/default/files/publications/rcbook/R-C_partnerships_BOOK.pdf

McMurtry, R., & Curling, A. (2008). Roots of Youth Violence.

Métis Nation of Ontario, Ontario Federation of Indigenous Friendship Centres, and Ontario’s Women’s Association. (2014). A Collaborative Submission regarding a Provincial Aboriginal Children and Youth Strategy. Retrieved from Métis Nation of Ontario as Printed Copies. (Confidential).

Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (nd). My Meds Rights: Information for Youth about Legal Rights and Psychotropic Medications. Retrieved from Ministry of Children and Youth Services as Printed Copy. (Confidential).

Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (nd). Information for Caregivers about Psychotropic Medications for Children and Youth. Retrieved from Ministry of Children and Youth Services as Printed Copy. (Confidential).

Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (nd). Focus on the Facts: Information for Youth about Psychotropic Medications. Retrieved from Ministry of Children and Youth Services as Printed Copy. (Confidential).

Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (nd). MCYS Foundation Decks. (Confidential).

Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (nd). Questionnaires. Crown Ward Review. (Confidential).

Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (nd). Policy and Procedure Manual for Regional Offices: Setting and Reviewing Rates per diem funded Children’s Residential Programs. Retrieved from Ministry of Children and Youth Services as Printed Copy. (Confidential).

Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (nd). Appendix A – Chart of Accounts – Residential Program. Retrieved from Ministry of Children and Youth Services as Printed Copy. (Confidential).

Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (nd). Youth Justice Framework – Introduction and Project Overview. (Confidential).

Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (1996). Fact Sheet: Consent and Rights under the Health Care Consent Act. Retrieved from Ministry of Children and Youth Services as Printed Copy. (Confidential).

Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (2001). Policy on the Use of Physical Restraints. Retrieved from Ministry of Children and Youth Services as Printed Copy. (Confidential).

Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (2001). Youth Justice Licencing Compliance Checklist. Retrieved from Ministry of Children and Youth Services as Printed Copy. (Confidential).

nistry of Children and Youth Services. (2001). Physical Restraints Approved Training Curricula. Retrieved from Ministry of Children and Youth Services as Printed Copy. (Confidential).

Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (2006). Physical Restraints Approved Training Curricula. Retrieved from Ministry of Children and Youth Services as Printed Copy. (Confidential).

Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (2008). Licensed Residential Setting Policy Requirement Police Record Check. Retrieved from Ministry of Children and Youth Services as Printed Copy. (Confidential).

Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (2010). Per Diem Rate Setting – 101 Team Orientation. Retrieved from Ministry of Children and Youth Services as Printed Copy. (Confidential).

Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (2010). Backgrounder – Licenced Residential Setting 101 – Team Orientation. Retrieved from Ministry of Children and Youth Services as Printed Copy. (Confidential).

Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (2011). Licenced Residential Settings Policy Requirement 2011-1 Safe Administration, Storage and Disposal of Medication. Retrieved from Ministry of Children and Youth Services as Printed Copy. (Confidential).

Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (2012). Stepping Stones: A Resource on Youth Development.

Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (2014). Measuring Impact. Inspiring Success.

Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (2014). Agency Report. Crown Ward Review. (Confidential).

Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (2014). Case Report. Crown Ward Review. (Confidential).

Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (2014). Crown Ward Review Orientation Process. (Confidential).

Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (2014). Licensing Renewal Forms and Documentation. (Confidential).

Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (2015). Responding to the Needs of Aboriginal Youth in Conflict with the Law. (Confidential).

Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (2015). The Youth Criminal Justice Act and Services for Aboriginal Youth in Ontario. (Confidential).

Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (2015). Youth Justice Services. (Confidential).

Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (2015). Roy McMurtry Youth Center: Overview Presentation. (Confidential).

Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (2015). Implementation of the Youth Justice Criminal Act (YJCA): Ten Years Later. (Confidential).

Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (2015). Youth Justice Services Division – Staff Training and Development Unit Annual Report – Fiscal year 2014-2015. (Confidential).

Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (2015). Youth Custody Facilities: Snapshots. (Confidential).

Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (2015). Child Welfare Funding Model. (Confidential).

Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (2015). Secure Treatment Programs in Ontario. (Confidential).

Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (2015). Custody / Detention Standards. Retrieved from Ministry of Children and Youth Services as Printed Copies.

Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (2015). The Report on the CFSA Review.

Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (2015). Residential Services for Children and Youth.

inistry of Children and Youth Services. (2015). Children’s Residential Licensing.

Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (2015). Scan of Residential Services in Jurisdictions outside of Ontario. (Confidential).

Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (2015). Literature Review: Residential Services for Children and Youth. (Confidential).

Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (2015). Children Residence Licensing Checklist Report. Retrieved from Ministry of Children and Youth Services as Printed Copy.

Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (2015). Youth Justice Agency List by City – Bed Capacity. Retrieved from Ministry of Children and Youth Services as Printed Copy. (Confidential).

Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (2015). Serious occurrence Reporting Procedures. Guidelines for the Annual Summary and Analysis Report – Appendix A. Retrieved from Ministry of Children and Youth Services as Printed Copy. (Confidential).

Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (2015). Serious Occurrence Report. Retrieved from Ministry of Children and Youth Services as Printed Copy. (Confidential).

Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (2015). Enhanced Serious Occurrence Report. Retrieved from Ministry of Children and Youth Services as Printed Copy. (Confidential).

Ministry of Children and Youth Services. (2015). Scan of Residential Services in Jurisdictions outside of Ontario. Retrieved from Ministry of Children and Youth Services as Printed Copy. (Confidential)Ministry of Health and Long Term Care. (nd). Long Term Care Deck. (Confidential).

Murray McKinnon Foundation. (2014). Annual Report. Retrieved from Murray McKinnon Foundation as Printed Copies.

Myhre, H.S. (2006). Radical Youth Work: Becoming Visible.

Neumann, B.R., (2000). Prospective Payment Systems: Evaluation and Implementation in Residential Treatment Centers. Residential Treatment for Children and Youth, 17(4) 31-54

Ninan, A., Kritter, G., Baker, L., Steele, M., Boniferro, J., Crotogino, J., Stewart, S., & Dourova, N. (2014). Developing a Clinical Framework for Children/Youth Residential Treatment. Residential Treatment for Children and Youth, 31,284-300.

Northern Youth Services. (2015). Building Strengths. Building Futures. Northern Youth Services Strategic Plan. Retrieved from Northern Youth Services as Printed Copies.

Office of the Auditor General of Ontario. (2015). Annual Report - Child protection services program.

Office of the Child and Family Service Advocacy. (2007). We Are Your Sons and Daughters.

Office of the Child and Youth Advocate, Alberta. (2012). Annual Report 2011-12 of OCYA, Alberta.

Office of the Chief Coroner. (nd). Youth Inquest Reports. Retrieved from Ministry of Children and Youth Services as Printed Copies.

Office of the Chief Coroner. (2015). Verdict of the Coroner’s Jury – Guy Mitchell.

Ombudsman Ontario. (2003). 2002-2003 Annual Report.

Ontario Association of Children’s Aid Societies. (2005). Journal Volume 49. Number 3.

Ontario Association of Children’s Aid Societies. (2006). Outside Paid Resources (OPR) Shared Services Project. Implementation Analysis Report. Retrieved from Ontario Association of Children’s Aid Societies as Printed Copies.

Ontario Association of Children’s Aid Societies. (2015). The Voice of Child Welfare in Ontario. Retrieved from Ontario Association of Children’s Aid Societies as an Electronic Copy.

Ontario Association of Residences Treating Youth. (2015). Partners in Care 6. Risk and Resilience.

Ontario Centre of Excellence in Children’s Mental Health. (2013). Evidence In-Sight.

Ontario Centre of Excellence for Child and Youth Mental Health. (2013). Evidence In-Sight Request Summary: Residential Crisis Respite Services. Retrieved from Ontario Centre of Excellence for Child and Youth Mental Health as Printed Copies

Ottawa Inuit Children’s Centre. (2013). Feasibility Study: Needs of Nunavut Children and Youth in Ottawa. Retrieved from Ottawa Inuit Children’s Centre in Printed Copies.

Ottawa Inuit Children’s Centre. (2015). Strengthening the Response to Nunavut Children and Youth in Ottawa. Retrieved from Ottawa Inuit Children’s Centre in Printed Copies.

Pavkov, T., Lourie, I., Hug, R., & Negash, S. (2010). Improving the Quality of Services in Residential Treatment Facilities: A Strength-Based Consultative Review Process. Residential Treatment for Children and Youth, 27,23-40.

Peel Children’s Aid Society. (2013). Peel Children’s Aid Society’s Annual Report 2012-2013.

Peel Children’s Centre. (2013). Strategic Plan 2013-2018.

Peel Children’s Centre. (2014). Annual Report 2014-2015.

Peel Children’s Centre. (2015). Services Report. Retrieved from Peel Children’s Centre in Printed Copies.

Provincial Advocate for Children and Youth. (2011). 25 is the new 21. Toronto, ON: Provincial Advocate for Children and Youth.

Provincial Advocate for Children and Youth. (2013). It Depends on Who’s Working.

Phelan, J. (2015). The long and short of it: Child and youth care. Cape Town, South Africa: The CYC-Net Press.

Roberts Smart Center. (2015). Best Practices.

Roebuck, B., & Roebuck, M. (2013). Group Care in the Child Welfare System: Transforming Practices. (Printed Copy).

Roy McMurtry Youth Centre. (2015). Guidelines, Templates, Procedures and Documentation. Retrieved from Roy McMurtry Youth Centre as Printed Copies. (Confidential).

Rubin, D.M., O’Reilly, A.L.R., Hafner, L., Luan, X., & Localio, A.R. (2007). Placement stability and early behavioral outcomes among children in out-of-home care. In R. Haskins, F. Wulczyn, & M.B. Webb (Eds.), Child protection: Using research to improve policy and practice (pp. 171-188). Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Runyan, D., & Gould, C. (1985). Foster care for child maltreatment: Impact on delinquent behavior. Pediatrics, 75, 562 – 568.

Ryan, J.P., & Testa, M.F. (2005). Child maltreatment and juvenile delinquency: Investigating the role of placement and placement instability. Children and Youth Services Review, 27, 227-249.

Sinha, V., Trocmé, N., Fallon, B., MacLaurin, B., Fast, E., Thomas Prokop, S. Richard, K. (2011). Kiskisik Awasisak: Remember the Children. Understanding the Overrepresentation of First Nations Children in the Child Welfare System. Ottawa, ON: Assembly of First Nations.

Sinha, V., & Wray, M. (2015). Foster Care Disparity for First Nations Children in 2011. Canadian Child Welfare Research Portal (CWRP) Information Sheet. Montreal, QC, Canada: Centre for Research on Children and Families, McGill University.

Smith, M. (2009). Rethinking Residential Child Care: Positive Perspectives. Bristol, UK: Policy Press.

Smith, M., Fulcher, L.& Doran, P. (2013). Residential child care in practice: Making a difference. Bristol, UK: The Policy Press.

Statistics Canada. (2015). Living Arrangements of Young Adults aged 20 to 29.

Taylor & Francis Group. (2009). Redefining Residential: Ensuring the Pre-conditions for Transformation through Licencing, Regulation, Accreditation, and Standards. Residential Treatment for Children and Youth, 26,237-240.

Taylor & Francis Group. (2015). Attitudes, Perceptions and Utilization of Evidence-Based Practices in Residential Care. Residential Treatment for Children and Youth, 32,144-166.

Taylor & Francis Group. (2014). A lattice of participation: reflecting on examples of children’s and young people’s collective engagement in influencing social welfare policies and practices. European Journal of Social Work, Vol. 17, No. 5, 718-736.

Toronto Star. (2015). Why are so many black children in foster and group homes?

Toronto Star. (2015). The Game: Living Hell in Hotel Chains.

Toronto Star. (2015). Sad Lessons from Katelynn Sampson’s Murder.

Toronto Star. (2015). Dad of Niagara Baby who died begged that boy not be placed with grandfather.

Toronto Star. (2015). Physical restraint common in Toronto group homes and youth residences.

Toronto Star. (2015). Shedding light on the troubles facing kids in group homes.

Trocmé, N., Esposito, T., Chabot, M., Duret, A., & Gaumont, C. (2013). Gestion fondée sur les indicateurs de suivi clinique: Rapport Synthese. Association des centres jeunesse du Quebec: Novembre 2013, pp 1-9.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Calls to Action. Retrieved from Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Winnipeg, Manitoba.

UK Government. (2016). Find an inspection report. Ofsted.

Ungar, M. (2002). Playing at being bad: The hidden resilience of troubled teens. Lawrencetown Beach, NS: Pottersfield Press.

Ungar, M. (2004). Nurturing hidden resilience in troubled teens. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

Ungar, M. (2015). I still love you: Nine things troubled kids need from their parents. Toronto, ON: Dundurn Publishers.

Watson, L., Hegar, R., & Patton, J., (2011). State/University Collaboration to Strengthen Children’s Residential and Placement Services. Residential Treatment for Children and Youth, 28,177-191.

Widom, C. (1991). The role of placement experiences in mediating the criminal consequences of early childhood. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 61, 195 – 209.

William W. Creighton Youth Services. (2015). Program Descriptions. Retrieved from William W. Creighton Youth Services as Printed Copies.

Youth Services Bureau. (2015). Impact tomorrow, today. Program Overview and Strategic Priorities. Retrieved from Youth Services Bureau as Printed Copies.