The effects of negative life events on brain development

Negative life experiences in childhood can be a significant source of stress. Children and youth are especially sensitive to stress because their bodies are still developing. Stress interferes with how various systems in our body develop and connect to each other. This interference can affect anything from our brain connections, to our behaviour, to our DNA. In other words, trauma can rewire various systems in the body.

Trauma is not just an event that took place sometime in the past; it is also the imprint left by that experience on mind, brain, and body.

– Bessel A. van der Kolk

Below is an overview of how trauma shapes the brain, body, and behaviour.

The Stress Response

When a child perceives a threat, their stress response is activated. This means that there is a sharp increase in stress hormones moving through the body. This makes the heart work harder and faster, increases breathing, and makes the child feel on-edge. The child may express their distress with crying, screaming, or becoming aggressive. Or, the child may withdraw and try to avoid the situation.

We produce stress hormones during an emergency. They prepare us to respond to a threat, and are helpful during emergency situations. However, if we are in "emergency" mode all the time, these hormones can become harmful to our minds and bodies. This can happen to children who have experienced trauma.

The stress of early negative life events can make a child more sensitive to stressful situations in the future. This means that years after the trauma occurred, when the child perceives a threat or danger, more stress hormones will move through the body for a longer period of time.

Toxic Stress

"Toxic stress" occurs when a child is stressed for a long period of time without a supportive adult relationship. Many factors can affect a caregiver's ability to respond to their child, including depression, mental health challenges, addiction, and domestic violence.

During childhood, toxic stress disrupts connections in the brain and in other organ systems. Young brains are very sensitive to stress hormones. Chronically high levels of stress hormones are known to affect brain development. Since early life is a major period of development, this can cause permanent changes in the way the brain develops. These changes are known to cause impairments in learning and behaviour. Some scientists refer to this as a "stress-shaped" brain.

The Brain

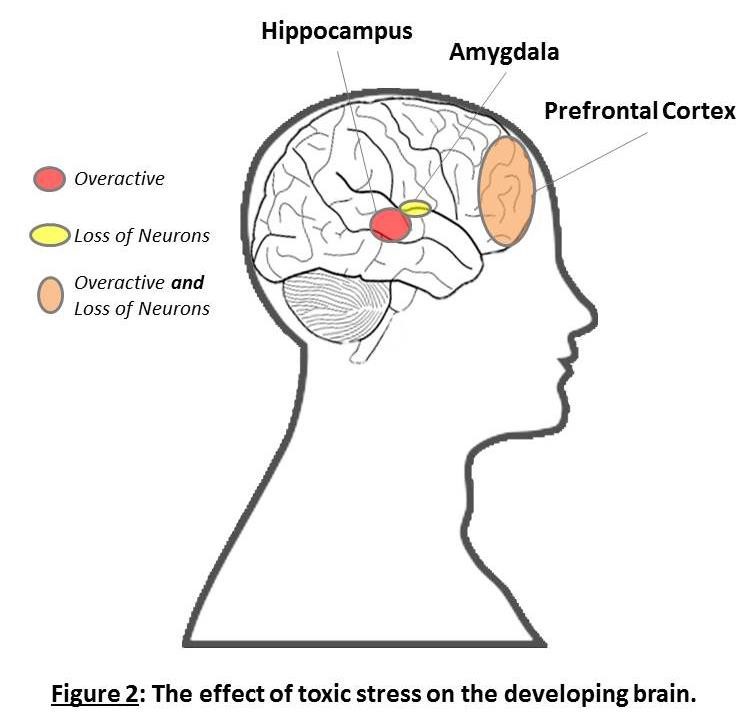

There are three main brain regions affected by negative life events in children: the amygdala, prefrontal cortex, and hippocampus.

| Amygdala | Prefrontal cortex | Hippocampus |

|---|---|---|

| Responsible for the response and memory of emotions, especially fear. | Controls complex behaviour, impulses, emotional reactions, personality, focus, planning, and ignoring external distractions. | Processes long-term memory and emotional responses. |

Chronic stress can cause some brain regions to become overactive, and others to lose connections. Sometimes, both can happen in the same region.

Losing connections in certain brain regions can make it difficult to separate what is safe and what is dangerous. Overactivity in some regions can lead to higher levels of stress, fear, and anxiety. Chronic stress can also affect the brain's ability to make decisions, self-regulate, control impulses, and access memory.

On the following page is a diagram (Figure 2) that outlines which brain regions experience a loss of neurons (the brain's "connecting" cells) and which brain regions become overactive.

Genetics

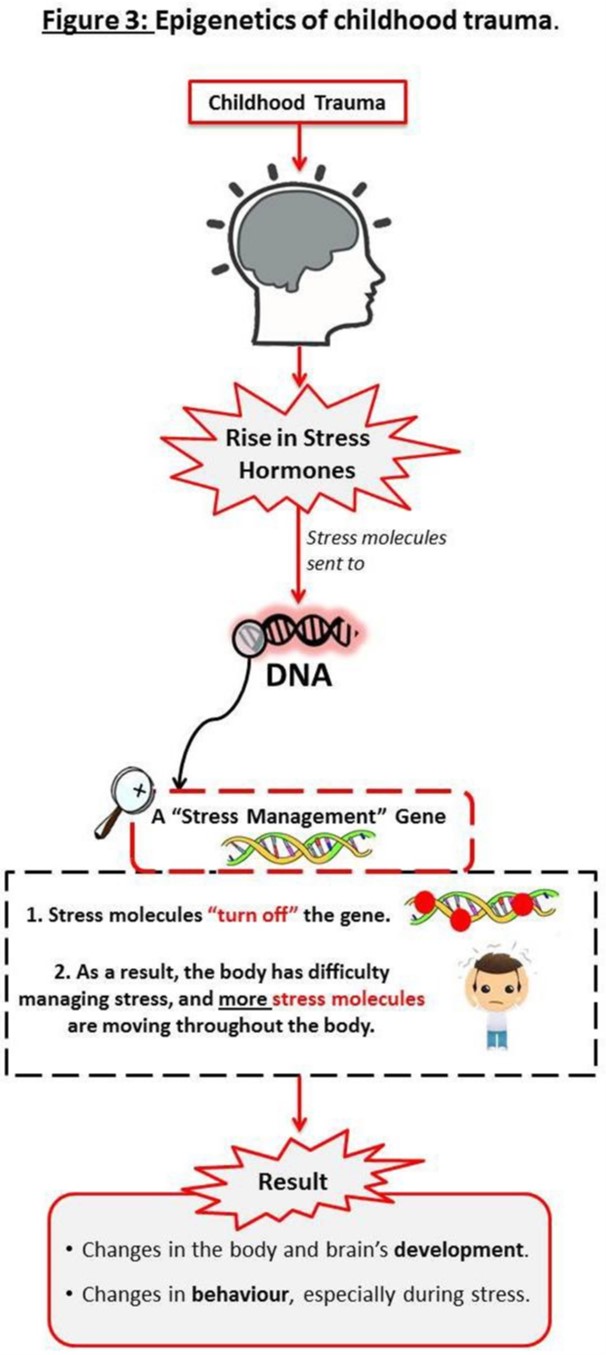

Our DNA contains the blueprints for the way we understand and respond to different situations. These blueprints are called genes.

We are born with a specific set of genes, and live with them our whole lives. While our genes do not change, our life experiences can affect the way these blueprints are used. This process is called "epigenetics".

Normally, our bodies have systems in place that signal the body to calm down and return to a relaxed state. In other words, these systems help us to manage our stress. Some of these systems are controlled by our genes—the blueprints in our DNA.

Many children who have experienced trauma have very high levels of stress hormones. This can cause genes that help manage stress to turn off. See Figure 3 for an overview of how this gene is switched off, and how the child is affected by this change.

If our stress management genes are switched off, it becomes very difficult for us to manage stress. The body can't signal itself to calm down.

This is why some children who have experienced trauma are on alert all the time. Innocent behaviour from others can be seen as threatening. Some children may also struggle with change and become aggressive.

Fortunately, this doesn't have to be permanent. A supportive relationship with an adult can help to switch the stress management gene back "on". This "on" switch means that the body can now signal itself to calm down and return to a relaxed state.

Re-Wiring: A Sense of Hope

Positive, responsive and consistent interactions with caring adults strongly influence brain development. Over time, these corrective interactions create strong connections in social and emotional areas of the brain, thus providing the traumatized brain with opportunity for "re-wiring". This takes time and much repetition. Building a relationship based on safety, trust, and communication are key to helping support your child in learning a new way to interact with the world.

"Being able to feel safe with other people is probably the single most important aspect of mental health; safe connections are fundamental to meaningful and satisfying lives."

– Bessel A. van der Kolk