Part 2: Learning from deaths by suicide and mental health issues in the context of policing

Our mandate was to examine deaths by suicide specifically among police officers. No doubt, much of the general knowledge and social science about suicide applies as much to this sub-set as it does to the general population. Police members are people first, and like everyone else, their lives are subject to the same successes, challenges and complexities as their non-policing peers. But, even the expression of our mandate implies that there might be something different from the norm in the pathways traveled by our nine, and by other police officers and civilian members that have arrived at the same tragic point outside the scope of our study. Our panel shared that same suspicion from the outset, and we set out to dive deeply into the question.

First, we noted that there is important work being done across Canada to better understand, through research, the mental health and well-being challenges faced by those in the policing profession, as well as in the broader community of first responders. Specific priority has been placed by the federal government on understanding and serving the mental health needs of public safety personnel in Canada through a number of efforts, including the passing of the Federal Framework on PTSD Act in 2018. The Canadian Forces has invested considerable research and development to better serve the mental health needs of active service members and veterans. Our panel recognizes the work of the Canadian Institute for Public Safety Research and Treatment (CIPSRT), the Canadian Institute for Military and Veteran Health Research (CIMVHR), their funding partners, and countless others working in this field for the commitment they have shown to improving outcomes for first responders, including police. The deliberations, conclusions and recommendations of our own panel are timely and relevant in the overall pattern of efforts in Canada in this regard.

We also note that there have been significant advances in mental health awareness and resilience training across Ontario police services in recent years, along with a growing number of staff and consulting psychologists embedded within the ranks to increase access to professional support and organizational guidance. In 2017, the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police (CACP) established a Psychologist Sub-Committee under its Human Resources and Learning standing committee in an effort to achieve greater alignment and to create a network of best practices, among other aims.

The Ontario Provincial Police (OPP) has been engaged in a multi-pronged examination of mental health and suicides among its members, and the efficacy of current mental health supports available through its partnerships with its principal collective bargaining units, the Ontario Provincial Police Association (OPPA) and the OPP Commissioned Officers Association (COA). They have also engaged within these studies the active support of charitable and not-for-profit agencies that provide peer support, early intervention, and health care referrals, most of them working on a volunteer basis. The OPP reviews are broader in scope than our review, spanning a longer time frame of lived experience and including extensive consultations with active and retired members. We were fortunate to have the opportunity to interact with their study team members, their executives, and the OPPA during our own deliberations, and to review some of their findings and several proposed and promising solutions that are well underway.

We also received delegations from the Toronto Police Association (TPA), the Police Association of Ontario (PAO), and the Ontario Association of Chiefs of Police (OACP), each of whom showcased progressive and encouraging steps being taken along with expanded services in place or under development. We gained an international perspective on emerging practices related to police well-being from a recent global scan executed and summarized for us by a team from Deloitte.

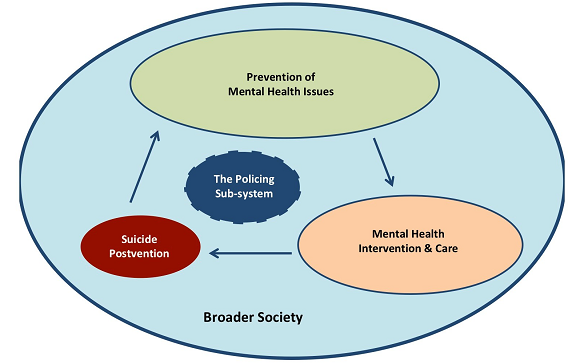

All of these discussions yielded a progressively clearer picture of a policing and mental health ecosystem (see Figure 2), as others have noted in their own research. In our view, mental health and wellness issues in general, responses to moderate to acute illness, and deaths by suicide must be situated and understood in this context if we are to change the conditions and reduce risk for all police officers and civilian staff.

Figure 2: A policing and mental health ecosystem

We note there is an extensive health and social infrastructure intended to serve the broader public across Ontario in every phase of prevention, as illustrated in Figure 2. And, we also learned of ongoing initiatives to strengthen those supports, reduce suicide risk, and improve mental health outcomes for everyone, including police members. We encourage interested readers to consider all of these ongoing efforts to improve outcomes. Within the scope of our own report, suffice to say that the evident levels of commitment to these issues within policing give strong evidence that there are indeed apparent and urgent differences from broader society in the pathways experienced by police officers and their civilian colleagues in the policing sector.

Through our own analysis and discussions, we developed several observations on factors that are either unique, or at least uniquely acute within policing culture. We outline below those we found most salient to our study, and we highlight them for their real and potential impacts upon the mental wellness of police service members in Ontario.

Stigma and self-stigma for mental health issues

We often hear of stigma as a major factor in how society responds to persons experiencing mental health issues, and we salute efforts such as the Bell Let's Talk initiative, anti-stigma outreach programs from the Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA), the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH), and a host of community based organizations and public and private sector agencies. No one is served well by a social prejudice that differentiates mental suffering from physical, and we believe outcomes would be considerably better for everyone if this false separation could be eliminated.

And so, the starting point for the average police member may be no different than for others. At least, that is, until they enter the academy, hit the streets, or begin to work at the communications centre. In most police jurisdictions across Ontario, estimates run as high as 40% of police calls for service being tied to incidents involving persons with mental health issues. Whether or not the police are the appropriate response in many of these cases is a topic of considerable debate and outside the scope of our study. But, the fact remains that within the first few years of service, a police officer, communicator, or other specialist will have come to recognize those with mental health issues among the highest frequency of calls, and often for patrol officers they may even rank among their primary encounters with the public. Sadly, if the police are being called, they may also be encountering such individuals at the very worst times and often under the most critical stages of their condition. And in extreme cases, these encounters may involve violence and a direct threat to the safety of the public and that of the responding officers. It is also worth noting that it is police officers that must respond to almost every suicide that occurs in the general public.

Police members have reported to us directly and in other studies we consulted that notwithstanding their high degrees of compassion, training and their on-scene professionalism that is the norm in these thousands of calls for service, most police members will soon come to regard any person with mental health issues as someone they would never want to be. They also told us that they often become disillusioned about the effectiveness of mental health care when they bring acutely mentally unwell people to hospital only to see them leave shortly afterwards with little to no change in their condition or circumstances.

The lifeline of police identity

Sworn police officers in Ontario and across Canada are invested with extraordinary responsibilities. They have the power under due circumstances to deny a person's freedom through arrest and detention, to enter private homes and communication devices with judicial authorization, to investigate and interrogate, to confiscate vehicles and other property, and when required, to apply escalating levels of force up to and including ending someone's life. They carry a range of use-of-force options on their duty belt and in their patrol car, and while they have an unenviable obligation to use them when warranted, they also carry the most exacting levels of accountability to formal authorities, to public oversight bodies, and to the informal world of mainstream and social media. When crisis or violence erupts, members of the public tend to move away from it, while police officers are duty-bound to move toward it. They must face it head on, often with great risk to themselves and their on-scene colleagues on whom they often must rely so that they remain safe and, so that no one else is injured.

Police officers represent 0.18% of the Canadian public (a number that is similar in Ontario). Put another way, 99.82% of Canadians do not carry these same authorities and responsibilities. Most police members will tell you that their career is not a job but a calling, and this distinction from almost all other Canadians is not lost on them. It is a source of great pride, and it carries its own burdens and every day stressors that most of us cannot imagine.

In any occupation, if a co-worker began to report or display mild symptoms of a mental illness, such as depression, anxiety disorder, or even moderate substance use, his or her colleagues might be alarmed, might recognize and pick up some workload imbalance, and might even be troubled periodically by behaviour they see as odd. It is doubtful that most co-workers would feel threatened by this individual's personal condition except in rare and extreme circumstances.

In policing, if a member reports or displays mild mental health issues, for at least some colleagues and even for the member himself or herself, such 'odd behaviour' can rise to life and death significance. It could be interpreted as, or merely feared to become a direct threat to the member and any colleagues who may be called to rely upon him or her at any time during a shift. While such dire situations may be infrequent in reality, they are by their nature unpredictable, and there is little margin for error when they occur. Apparently, from members' own disclosures, this is not lost on the average police officer, ever.

When combined with the self-stigma described above, this fear of being the one to let down the team may be even greater for the officer with the mental health issue, no matter how mild or moderate, than it is for his or her colleagues. Officers are trained to be team players and in truth, they will typically support one another. But, this may not be what goes through the mind of the afflicted. Instead, due to the early training and conditioning and the ongoing workplace culture of policing, many officers report becoming quite binary in their view of such things: either you are fit for duty, or you are not. As such, any loss or limit on your ability to perform the full scope of your duties can amount, in the mind of the individual, to a loss of your identity as a police officer.

Interestingly, this is not usually the same, or at least is not experienced to the same degree, if the deficiency arises from a physical injury or illness. Injuries are not uncommon in police work or even in off-duty activities. Illnesses can affect everyone in relatively uniform measure. Police can be very supportive, and when illnesses or injuries are severe, they often exhibit outstanding levels of support for their ill or injured colleagues.

But, likely due to the stigma and self-stigma they share, when the deficiency is due to psychological injury or arises from the same forms of mental health issues that affect 20% of all Canadians, the harsh and unfortunate term that is often invoked in policing is "broken toys". In other words, you are no longer fit for duty. And, as we all recall from childhood, once broken, most toys cannot be fixed.

Faced with this harsh and often binary reality, a great number of police members will deny and shield the presence of mental health issues for as long as they can. The literature suggests that they may turn, in greater than average numbers, to alcohol and other substance use, and other often harmful self-medicating activities, in efforts to mitigate symptoms and to contain their underlying issues from exposure and treatment. Despite considerable investments by police services in their human resource departments, employee and family assistance programs (EFAP), and many other supportive options, many will avoid such doorways out of fear of exposure.

Too often, by the time their condition either forces them to seek help of their own accord, or is recognized by others or by consequences that leave them no choice but to seek help, they will have already traveled well down all three of the pathways described above. They may be at a point of greater criticality in their mental health issues. They may have a narrower range of secondary prevention and care options available to them. And, with surprising frequency, they may be experiencing disconnection due to damaged relationships with their employer, their colleagues, their friends, and their family as a result of their unmanaged illness and/or their unhealthy reliance on intoxicants.

The high costs of accommodation

In the best cases, members who recognize or are recognized early for mild to moderate mental health conditions will be quickly and effectively connected to the professional services and guidance they require. Enter the high personal costs and heightened risks that stem from accommodation. This is a term, and a status, that can be almost as loaded and stigmatized as mental illness itself in the policing culture.

If you are being accommodated by the organization, there are very differing responses that might apply. If you are still able to come to work and execute tasks that remain central to the mission, you are still serving your calling. Even if there are restrictions placed on your attendance, your deployment or your range of duties, and others know this to be due to a temporary or even permanent physical injury or illness, you may still be regarded as a dedicated and courageous member for continuing to serve when and where you can.

But, something appears to change if the reasons for modified duty or extended absence from work are left open to speculation and rumour, as can often be the case when a member chooses to remain private about mental health issues they are experiencing, or about the nature of their treatment and path to recovery. Stigma and misinformation about mental health care and recovery can lead to harsh and even hostile presumptions among peers, supervisors and managers that a member's behaviour is simply malingering, especially where there have been past performance issues or workplace conflict. This despite evidence that real malingering is actually quite rare. And, to quote one demeaning descriptor used by some, a member has been reduced to "counting paper clips" if a reassignment falls far outside their usual scope of duties, notwithstanding that it is still significant and dignified work.

Again, it is easy to see how quickly and how much further a member being accommodated for mental health reasons under these prevailing conditions might travel down those three pathways. Some may deny their own conditions completely, or deny themselves access to the care and treatments available due to self-stigma and cultural perceptions. Even if receiving care, the motivation will be very strong to suppress symptoms, to exaggerate wellness, and if accommodated or absent, to push hard toward full reinstatement, thus risking an increase in the criticality of the underlying mental health issues. The tendency to eschew available supports and services will be a common tactic to remain unrestricted in one's duties. If performance issues or conflicts with supervisors begin to surface, it may be without the benefit of true explanation. And, these additional stressors and ongoing deceptions at work and at home will often continue to deepen other actual and emotional disconnections from family and friends, especially when substance use also increases as a chosen means of coping.

The give and take of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) presumptive policy in Ontario

An operational stress injury (OSI is a non-medical term that is generally defined as “persistent, psychological difficulties resulting from operational duties”

The Ontario legislature passed presumptive legislation in 2016, expediting access to Workplace Safety and Insurance Board (WSIB) benefits, and by extension access to care for members who have been diagnosed by a psychiatrist or psychologist. It is no longer necessary to establish a causal link between a specific traumatic event and the condition. There is little doubt that this step has brought many more police officers to the care they require while also reducing the burden and added stressors of justifying their condition on the basis of a single traumatizing experience.

However, the panel observed two difficulties that have arisen, perhaps as unintended consequences from this progressive policy. The first is that WSIB and clinicians are still required to adjudicate the general pattern of trauma in order to exert some measure of control over the uptake of these benefits and services. As such, while a single precipitating event might not be required, some police officers experiencing symptoms of PTSD might still find themselves trying to justify their basis, and if unsuccessful and benefits are denied, to pull away from the care they require due to cost and now worsened self-stigma.

The second concern is that while the presumption opens a path to care for PTSD, it may inadvertently be closing down other paths to care for more generalized mental health conditions, including the broader range of occupational stress injuries. This can lead to misdiagnosis and over-diagnosis of PTSD on the one hand, since that is where the benefits are most accessible, and it can leave those experiencing such conditions as depression, anxiety disorders and substance use disorders without similar access and/or self-justification, on the other.

There is no doubt that trauma is a real and present danger in police work, and recent research is revealing more about and reducing stigma around the genuine nature of OSI's being experienced by military veterans and first responders across the board. However, just as PTSD is gaining legitimacy as one condition, our panel recognized the potential risk of narrowing the lens through which we view the entire spectrum of mental health challenges to which police officers may be prone.

The confounding interplay among workplace stressors and life events for police

It seems likely that any person who experiences a decline in their mental wellness might struggle to distinguish the roles played by the stresses of everyday living versus those that have come from earning a living. Nonetheless, our panel observes that there is an interplay among these sources that may be even more complex for police than for others. As our nine subjects traveled down those three pathways to their tragic point of convergence, most had become disconnected from their employer and organizational supports, and at the same time, most were also disconnecting from their family, friends and social supports, if not in actual terms, then certainly to significant degrees of emotional detachment. The inherent danger in this observation is that one might be easily inclined to attribute their condition to on-the-job trauma and/or workplace dynamics, and miss the corresponding stressors playing upon them from their interpersonal conflicts, economic challenges, and other stressors of everyday life. Or, since in most of our cases and others we reviewed the most apparent precipitating events actually derived from outside of work, it would be just as easy to ascribe their state of health to everyday life alone, and to discount the roles played by their career-long experiences.

What makes this dilemma important in the context of policing is the interwoven nature of police identity as described above. Many police members have described the difficulties they face in even recognizing the distinction between work life and home life. The difference between on and off duty for a police officer is merely a distinction of pay and equipment because in Ontario, once sworn, a police officer carries his or her authorities and responsibilities 24 hours a day. Since they tend to see themselves serving and defined by a calling, and they operate tightly within a team culture that is unique in society for its rights and its responsibilities, their identity tends to travel with them. Many have described the way their children, spouses and significant others view them as heroes. As such, disappointing one's colleagues on the job may also be, in their own perception, to disappoint those others outside of work and to fall short of that important identity for everyone.

An enduring commitment to duty despite the personal costs

Our final observation on the peculiarities of the policing context requires a disclaimer: neither a study of police deployment options, nor a full appreciation of the economics of policing fell within our scope. We did recognize that like all public services, police budgets must be managed and sometimes resources must be constrained.

Nonetheless, it appears to us as a panel that police resources in Ontario are strained to a breaking point in many locations around the province. It follows that mental health impact can be expected to continue and perhaps even grow in frequency and intensity if this situation is not somehow addressed.

These resource shortages may be real or perceived. They may be due to an inability or unwillingness to implement new models and re-engineered practices as some might suggest. They may be due to an unwillingness of local, provincial and federal governments to meet the real budget requirements as others would argue. They may be due in part to a vicious circle where each new accommodation of a member with mental health issues further aggravates already diminished staffing levels. But, while decision makers grapple with these arguments, police members are burning out, many are becoming ill, and some are dying.

It is in their nature to keep coming to work. It is in their nature to deploy into harm's way even when understaffed. It is also in their nature to minimize and suppress their own symptoms until they can no longer do so.

Footnotes

- footnote[1"] Back to paragraph Public Safety Canada (2019). Post-traumatic stress injuries and support for public safety officers.