Part 1: Understanding the common tragedy in any death by suicide

Our panel consisted of eight members selected by the Chief Coroner of Ontario for the expertise and perspective that each member could bring to the review. Several members are mental health professionals with expertise in suicide and suicide prevention, with experience working with police and other first responders. Others are current or past members of police organizations representing executive ranks, civilian specialties, and front line police officers with lived experience. One member is a mental health professional with extensive experience working with a police service outside of Canada, which has a reputation for excellence in promoting member mental health and well-being. One member is an educator and researcher with a special interest in policing culture. An early priority for the panel was to share their expertise and find a common frame of reference for understanding suicide. Following a discussion of the literature and the task at hand, two well-researched models for understanding suicide appeared to best fit the requirements for the review, the Canadian Forces Modified Mann Model for Suicide Prevention, and the Policing and Mental Health Ecosystem, and both are discussed further below. The panel also received input from outside delegations. We accessed a wide range of literature on the subject, digested other models from medical and sociological research, and we consulted the notes and themes culled from often painful interviews with survivors.

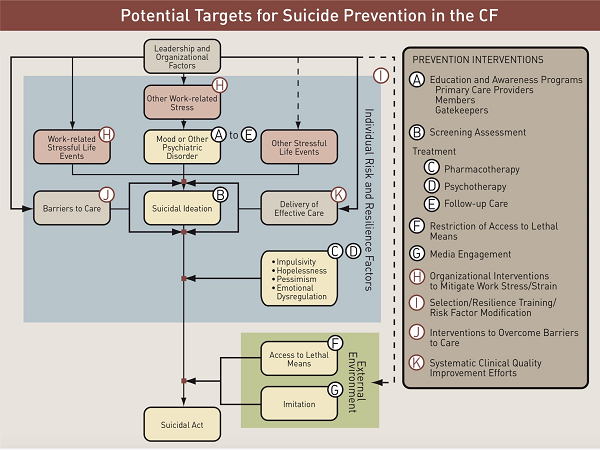

We learned that there is no prototype. Each and every suicide, whether attempted or completed, is in many ways as unique as the person involved. Although there is no single pattern that all suicides follow, the panel reviewed commonly studied and accepted factors associated with death by suicide. These include the presence of a mental health problem, often depression, combined with: a stressful life event or significant loss, which may be personal (loss of an important relationship through separation or divorce); experiencing stressful or overwhelming events related to work, such as violence or loss of status; or stress due to other factors (especially those causing embarrassment or shame). These conditions and events may then lead vulnerable persons to start thinking of suicide as a “way out”, or a way to solve their problems. There are then a number of factors, which have been shown to increase a person’s chances of acting on these thoughts and dying by suicide. These factors include: impulsivity, where either the person acts quickly and without much consideration, when a method of suicide is close at hand; or, the person uses drugs or alcohol which can decrease impulse control and lead to impulsive action; hopelessness or pessimism, where the person no longer believes there can be positive solutions or outcomes for them; emotional dysregulation, where the person is having difficulty controlling or moderating their feelings and behavior, and may be angry, aggressive, or prone to risk-taking; access to lethal means, where the person has a lethal method of death close at hand, which gives them no chance to deliberate on their actions, and kills quickly; and, contagion or imitation, where a vulnerable person learns of the death by suicide of someone whom they admire, or with whom they identify, and suicide begins to look like a “reasonable alternative” to the stresses and problems the vulnerable person is facing (the phenomenon of “copycat suicides” when the suicide of a public figure or celebrity is widely publicized is an example of this).

While hope and opportunities for intervention will always remain, once a clear intention to end one's life has been formed, options narrow considerably for preventing that death. There are many more opportunities before that point to prevent that decision from being made.

We recognized a distinctive pattern that would prove vital to our deliberations, a pattern that was also clearly evident in our nine subject deaths. We observed that by the time each of our subjects formed that determined intention to end his or her life, each had traveled a series of pathways, and each pathway had reached its end. The intersection of three specific pathways stood out for us. One is the path of acute mental health issues, often with associated substance use disorders. Another is the path of lost or diminished access to timely and quality care, effective treatment services and a range of essential supports. And the final one is the path of actual or perceived emotional disconnection from family, friends, and organization, often pushed to its endpoint by one or more precipitating events, sometimes at work, and more often in personal and family life.

We recognize that this observation may not break new ground in medical science, but our own discussions of this evident pattern proved instrumental in shaping the direction of our review. We recognized that we would be greatly limited if we were to direct our efforts solely to 'preventing suicides', per se. On the other hand, the imagery offered by these three critical pathways and their ultimate tragic convergence opens a much wider field of opportunity for changing the conditions. We know that if these conditions are unchanged, they will continue to lead some to that ultimate point of despair, and they will most certainly lead too many others to experience deterioration in the quality of their life and career. It is on these upstream aims and opportunities for improvement that we have chosen to focus this report.

We reviewed available literature and best practices in suicide prevention with a view to anchoring our own work in credible models. We noted that the US Air Force implemented a comprehensive suicide prevention program to reduce the risk of suicide, implementing 11 initiatives aimed at strengthening social support, promoting development of social skills, and changing culture to encourage effective help-seeking

In many ways, the CF-modified Mann model

Figure 1: Canadian Forces Modified Mann Model for Suicide Prevention

We include in our recommendations (see Part Five below) a call for further research and development that might lead to a police-specific version of the CF-modified Mann model for broad application across the sector, incorporating any additional factors and interconnections addressed within this report.

Footnotes

- footnote[1] Back to paragraph USAF (2001). The Air Force Suicide Prevention Program: A description of program initiatives and outcomes (AFPAM 44-160). Suicide Prevention Resource Center.

- footnote[2] Back to paragraph Mann JJ, Apter A, Bertolote J, Beautrais A, Currier D, Haas A et al. Suicide prevention strategies: a systematic review. JAMA 2005 October 26;294(16):2064-74.

- footnote[3] Back to paragraph Report of the Canadian Forces Expert Panel on Suicide Prevention