Chief Drinking Water Inspector Annual Report 2012-2013

The 2012-2013 Chief Drinking Water Inspector’s report provides detailed performance reviews of drinking water systems in Ontario, along with inspection results for those systems. This report also discusses the actions the Ministry of the Environment and others take to protect Ontario’s drinking water.

Information on individual inspection ratings, drinking water quality results for municipal residential drinking water systems and details of orders and convictions for drinking water systems and licensed and eligible laboratories can be found in this report’s Appendices, available on the Drinking Water section on Ontario’s website.

Message from the Chief Drinking Water Inspector

I am pleased to share this annual report with you, and showcase the achievements of the ministry and our drinking water partners during 2012-13.

Ontario’s drinking water continues to be among the best protected in North America, thanks to our comprehensive drinking water safety net that starts from our drinking water sources and continues until you turn on your tap. Our multi-barrier approach sets a world-class example, and we continue to be a leader in drinking water safety.

Ontario’s regulated drinking water systems and laboratories that analyse our drinking water samples continue to successfully meet the province’s regulatory requirements, as proven through test results of drinking water samples and inspections. In 2012-13:

- 99.88 per cent of more than 530,000 drinking water test results from municipal residential drinking water systems met Ontario’s strict drinking water quality standards.

- 99.7 per cent of inspections of municipal residential drinking water systems resulted in inspection ratings higher than 80 per cent, and 68 per cent scored 100 per cent.

From our comprehensive legislation to protect source water to our stringent health-based drinking water quality standards, we continue to work vigilantly with our partners and stakeholders to provide the highest quality drinking water to the people of Ontario today and for future generations.

This report also includes a message from Ontario’s former Chief Medical Officer of Health, Dr. Arlene King, as well as information on small drinking water systems that are regulated by the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care.

I encourage you to read this report to learn more about the excellent quality of Ontario’s drinking water, inspection results of drinking water systems and laboratories as well as the ministry’s enforcement activities. You can read more about our source-to-tap programs on the Drinking Water section on Ontario’s website.

Susan Lo,

Chief Drinking Water Inspector

Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change

Protecting Ontario’s drinking water

Ontario’s drinking water safety net

Ontario’s drinking water safety net is a multi-barrier approach to protecting our drinking water. Strong legislation, stringent health-based drinking water quality standards, regular and reliable testing, highly trained operators, regular inspections and a comprehensive source protection program, all work together to protect the safety of our drinking water.

Figure 1: Ontario’s drinking water safety net

The ongoing success of our safety net is the result of continuous collaboration between our many partners including municipalities, system owners and/or operators, local health units, laboratories, the Walkerton Clean Water Centre and stakeholder associations. It includes:

- Source-to-tap focus: safeguards are in place at every step of the process to address risks to the quality of drinking water, and identify potential issues before problems occur.

- Strong legislative and regulatory framework: the Safe Drinking Water Act, the Clean Water Act and their regulations help form the foundation for our safety net.

- Health-based standards for drinking water: our standards are based on the best available science, and are regularly reviewed to provide protection.

- Regular and reliable testing: licensed and eligible laboratories1 (laboratories) test hundreds of thousands of drinking water samples from the regulated systems to ensure our drinking water quality meets Ontario’s stringent health-based standards.

- Swift, strong action on adverse water quality incidents: this critical component of our safety net ensures effective oversight, strict monitoring and prompt action if an event such as an adverse test result occurs.

- Mandatory licensing, operator certification and training requirements: licensed municipal drinking water systems, well-trained and certified drinking water system operators and municipal drinking water system owners across the province are a key component of the safety net.

- A multi-faceted compliance improvement toolkit: we use a risk-based approach to improving compliance, increasing awareness and enabling informed and effective actions, conducting targeted inspections to confirm compliance and, where necessary, enforcement actions to address significant non-compliance issues.

- Partnership, transparency and public engagement: we work with many partners to deliver high-quality tap water for the people of Ontario, and produce the Chief Drinking Water Inspector’s and the Minister’s Annual Reports on Drinking Water.

Thanks to our strong framework of protection and the safeguards at every step of the process, people of Ontario can be confident in the quality and safety of their drinking water.

Source water protection

We continue to see significant progress in source water protection. The ministry has received all source protection plans from 19 local source protection committees. With the help of our many partners including local source protection committees, source protection authorities and First Nations, we are completing source-to-tap drinking water protection. This will help enhance the quality of life for Ontario families and support sustainable communities now and into the future. When completed, watershed-based source protection plans will safeguard more than 450 municipal residential drinking water systems. In addition, three First Nations drinking water systems have been included in the source protection process through a Lieutenant Governor-in-Council regulation amendment under the Clean Water Act.

As of April 30, 2014, the ministry has approved the Lakehead Source Protection Plan in the Thunder Bay area, the plan for the Niagara Peninsula and the Mattagami plan for the Timmins area. Plans are coming into effect and the province and its partners including municipalities, source protection authorities and local health boards are preparing to implement the related policies and report on progress. They have begun examining their internal processes to determine what changes are necessary to ensure their plans can be implemented.

To help small, rural municipalities prepare to implement actions that will protect local sources of drinking water, the government is providing $13.5 million of funding through the Source Protection Municipal Implementation Fund.

One hundred and eighty-eight small, rural municipalities are receiving one-time grants ranging from $15,000 to $100,000 to help offset some of the start-up costs as these municipalities prepare to implement their local source protection plans.

To assist our local partners including municipalities, who play a key role in implementing source protection plans, we provided risk management officials and inspectors a ministry-approved training program to help them fulfil their responsibilities under the Clean Water Act. As of April 30, 2014, more than 190 risk management officials and inspectors have taken this training program.

The ministry continues to fund conservation authorities, which are instrumental in supporting the review and approval of source protection plans, and helping source protection partners prepare for implementation.

To find out more about drinking water source protection in your local source protection area, please visit the Conservation Ontario website.

Statutory standard of care

Municipal officials play an important role in protecting public health by providing responsible and diligent oversight of their community’s drinking water.

Under Section 19 of the Safe Drinking Water Act, people with oversight responsibilities for a municipal drinking water system must exercise a level of care, diligence and skill that a reasonably prudent person would be expected to take in a similar situation. They are required to act honestly, competently and with integrity with a view to ensuring the protection and safety of the communities that are served by the municipal drinking water system. The standard of care applies to:

- the owner of a municipal drinking water system

- directors and officers of corporations if the municipal drinking water system is owned by a corporation other than a municipality

- those who oversee the accredited operating authority or exercise decision making authority over the system

The Walkerton Clean Water Centre offers a training course for municipal officials to help them understand their role in ensuring safe drinking water for their community, and to help them provide better oversight of drinking water systems. The ministry also published a guide entitled, "Taking Care of Your Drinking Water", which is available on the Drinking Water section on Ontario’s website.

The course and guide help municipal officials understand their responsibilities, and help ensure drinking water standards are maintained and public health is protected. As of March 31, 2014, 1,362 municipal officials have received training.

Municipal Drinking Water Licensing Program

Our Municipal Drinking Water Licensing Program is designed to ensure the people responsible for managing and operating our regulated systems meet regulatory requirements and have the skills and qualifications they need. All of Ontario’s municipal residential drinking water systems require a licence as part of the Municipal Drinking Water Licensing Program. To become licensed, an owner may require the following:

- a financial plan for their system

- a permit to take water

- a drinking water works permit

- an operational plan that is based on the Drinking Water Quality Management Standard

- an operating authority for the system that has received accreditation based on a third-party audit of their Quality Management System

Since issuing the first licences and permits in 2009, the ministry has been monitoring the program’s implementation and consulting with owners and operators to identify opportunities for continuous improvement.

The ministry has worked closely with the Walkerton Clean Water Centre since 2012 to hold a series of provincial workshops which provide attendees a forum to establish peer support networks and share best practices on Quality Management Systems. We continue to collaborate with the Walkerton Clean Water Centre to identify and respond to any additional needs for further guidance.

Municipal drinking water licences are valid for five years, and many came up for renewal in 2014. The ministry is committed to working with system owners to help them meet their renewal requirements.

Ontario’s drinking water report card

Ontario’s regulated drinking water systems continue to deliver high-quality drinking water. The year-over-year results clearly demonstrate that the quality of our drinking water is consistently high and it continues to meet the province’s health-based standards.

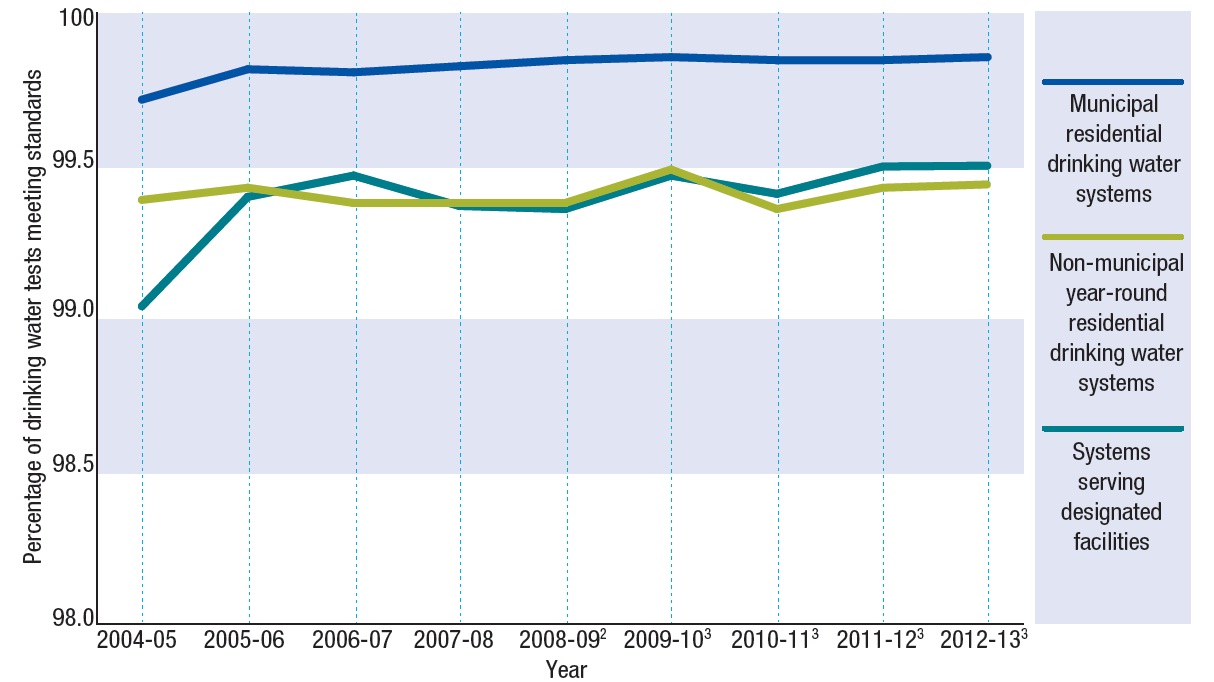

Figure 2: Trends in percentage of drinking water tests meeting standards, by facility type 1

1 There were slight variations in the methods used to tabulate the percentages year-over-year due to regulatory changes and because different counting methods were used.

2 Lead results were not included as they were reported separately.

3 Lead distribution results were included and lead plumbing results were reported separately.

Drinking Water Quality Standards

Ontario’s drinking water must meet 158 strict health-based standards for microbiological, chemical and radiological parameters. These standards are listed in O. Reg. 169/03 of the Safe Drinking Water Act.

Most of the Ontario Drinking Water Quality Standards are based on Health Canada’s Canadian Drinking Water Quality Guidelines which are developed by the Federal-Provincial-Territorial Committee on Drinking Water, which includes Ontario. When developing these standards, Health Canada also collaborates with international organizations such as the World Health Organization and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Health Canada regularly evaluates the existing Canadian Drinking Water Quality Guidelines to determine whether any new information on health impacts or treatment technologies has become available. It also reviews new scientific information and national drinking water surveillance data to determine if guidelines for new substances are required.

Drinking water quality: test results by parameter

Through regular monitoring of Ontario’s drinking water, we ensure our regulated drinking water systems continue to provide high-quality drinking water. Regular testing of Ontario’s drinking water is carried out by laboratories that are regulated under the Safe Drinking Water Act and the Drinking Water Testing Services Regulation (O. Reg. 248/03). This legislation describes regulatory requirements of testing laboratories and the tests they can perform, as well as tests that can be carried out by a system operator.

Reporting requirements

If a laboratory determines that sample test results have concentrations over the prescribed standards of any parameters, they must report the adverse test result immediately to the:

- ministry’s Spills Action Centre; and the

- local medical officer of health; and the

- operating authority and/or owner of the drinking water system if appropriate

In addition, the operating authority and/or owner of the drinking water system must be available to be notified immediately of the adverse result of a drinking water test. They must also immediately notify the ministry’s Spills Action Centre and the local medical officer of health. This duplication of reporting is a key component of Ontario’s safety net. It ensures all appropriate notifications are made and corrective action(s) are taken.

The following section of this report covers results from drinking water quality testing, which are measured against our stringent standards for microbiological, chemical and radiological parameters.

Types of corrective actions

The Safe Drinking Water Act requires taking corrective action when and where an adverse water quality incident is reported. This is a critical component of Ontario’s drinking water safety net.

Corrective actions depend on the type of incident and facility. Some of the corrective actions required by the Safe Drinking Water Act include one or more of the following:

- resampling and retesting

- immediately flushing the system

- reviewing operational processes to identify and correct faulty processes

- increasing chlorine/chloramine doses and flushing the system

- take such steps as are directed by the local medical officer of health

In response to an adverse water quality incident, the local medical officer of health may issue a boil water advisory or a drinking water advisory or require a system owner and/or operator to take one or more of the following actions:

- resample and retest at the same location or multiple locations

- bag the drinking water fountains in the case of a lead exceedance

- post signs advising the public not to drink the water

- provide alternate sources of drinking water

When an adverse incident occurs, ministry staff and local public health units work with affected system owners and/or facilities to ensure corrective actions are appropriately taken. If the issue is ongoing, ministry staff — in collaboration with local public health units and the system owner(s) — will continue to monitor the incident until it is resolved. Once the issue has been resolved, all corrective actions must be identified and reported to the ministry.

Microbiological test results and standards

The provincial regulations require that drinking water samples be regularly tested to detect the presence of microbiological organisms, total coliforms and Escherichia coli (E. coli) bacteria. The presence of these organisms in drinking water may indicate microbiological contamination with a potential to cause serious health problems. For this reason, Ontario’s Drinking Water Quality Standards require that total coliforms and E. coli not be present in drinking water samples. If these parameters are positively confirmed, an adverse water quality incident has occurred requiring immediate mandatory reporting and corrective actions by the system owner and/or operator.

The following table shows the results of microbiological tests for the 2012-13 reporting year.

| Drinking water facility type | Parameter | Total number of test results | Total number of test results meeting standards | Total number of adverse test results | Total number of systems submitting test results 1 | Total number of systems with adverse test results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Municipal residential systems | E. coli | 234,785 | 234,749 | 36 | 657 | 30 |

| Municipal residential systems | Total coliform | 234,829 | 234,385 | 444 | 657 | 174 |

| Non-municipal year round residential systems | E. coli | 15,479 | 15,469 | 10 | 434 | 9 |

| Non-municipal year round residential systems | Total coliform | 15,483 | 15,343 | 140 | 434 | 71 |

| Systems serving designated facilities | E. coli | 21,993 | 21,980 | 13 | 1,369 | 13 |

| Systems serving designated facilities | Total coliform | 22,003 | 21,793 | 210 | 1,369 | 125 |

1 Regulatory requirements for testing vary by category and source of water and are identified in O. Reg. 170/03.

A comparison of drinking water test results over the past nine years indicates that the percentage of municipal residential drinking water systems that met microbiological standards has remained consistently high.

| Municipal residential drinking water systems | Percentage of drinking water tests meeting standards | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004-05 | 2005-06 | 2006-07 | 2007-08 | 2008-09 | 2009-10 | 2010-11 | 2011-12 | 2012-13 | |

| E. coli | 99.97 | 99.99 | 99.98 | 99.99 | 99.98 | 99.99 | 99.99 | 99.98 | 99.98 |

Chemical test results and standards

Ontario’s Drinking Water Quality Standards also establish maximum acceptable concentrations for chemical parameters in drinking water. Some of these adverse test results may be due to naturally occurring deposits such as barium, fluoride and/or selenium.

The following table provides a list of the chemical adverse test results that were reported in 2012-13.

| Parameter | Total number of adverse test results | Total number of systems with adverse test results 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Barium 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Bromate | 3 | 1 |

| Fluoride 3 | 64 | 16 |

| Lead 4 | 28 | 17 |

| Selenium 3 | 9 | 1 |

| Total trihalomethanes 5 | 43 | 20 |

| Total number of systems submitting results | 660 | |

| Parameter | Total number of adverse test results | Total number of systems with adverse test results 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Antimony | 1 | 1 |

| Barium 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Fluoride 3 | 24 | 11 |

| Lead 4 | 3 | 2 |

| Nitrate (as nitrogen) | 16 | 6 |

| Nitrate + nitrite (as nitrogen) | 16 | 6 |

| Total trihalomethanes 5 | 7 | 3 |

| Uranium 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Total number of systems submitting results | 399 | |

| Parameter | Total number of adverse test results | Total number of systems with adverse test results 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Barium 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Benzo[a]pyrene | 1 | 1 |

| Fluoride 3 | 20 | 10 |

| Lead 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Nitrate (as nitrogen) | 37 | 13 |

| Nitrite (as nitrogen) | 1 | 1 |

| Nitrate + nitrite (as nitrogen) | 36 | 13 |

| Uranium 3 | 3 | 2 |

| Total number of systems submitting results | 1,285 | |

1 Sampling frequency varies according to regulatory requirements and facility type.

2 A single system could have adverse test results for multiple parameters. For the calculation of total number of systems with adverse results, a system with adverse test results across multiple parameters is counted only once.

3 In some parts of the province, there are naturally occurring deposits of barium, fluoride, selenium and uranium that may result in adverse test results.

4 The lead parameter did not include lead sampled in plumbing for municipal residential and non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems; however, lead sampled in the distribution system was included.

5 Total trihalomethanes are reported as the running annual average of quarterly samples.

Radiological test results and standards

O. Reg. 169/03 sets the drinking water quality standards for radiological parameters. In some parts of the province, there are naturally occurring deposits of uranium, requiring regular drinking water testing to monitor the levels of radiological parameters in the water. In accordance with their drinking water licence requirements, some drinking water systems, whose source waters contain these naturally occurring parameters, are required to sample and test for these parameters. No radiological adverse test results were reported in 2012-13.

Drinking water quality: test results by system type

The following section of the report includes additional drinking water quality test results for different types of systems. The percentage of all systems with drinking water test results that met our stringent standards for microbiological, chemical and radiological parameters continues to remain consistently high. Overall, in 2012-13, 99.8 per cent of test results submitted to the ministry met the provincial standards.

Municipal residential drinking water systems

Ontario’s municipal residential drinking water systems continue to deliver high-quality drinking water, as confirmed by test results submitted by laboratories to the ministry for 661 municipal residential drinking water systems. In 2012-13, the ministry received 531,859 drinking water test results. Almost 100 per cent of these results met Ontario’s rigorous standards.

| Parameter | 2010-11 % meeting standards | 2011-12 % meeting standards | 2012-13 % meeting standards |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microbiological1 | 99.90 | 99.89 | 99.90 |

| Chemical2 | 99.67 | 99.69 | 99.76 |

| Radiological | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Total | 99.87 | 99.87 | 99.88 |

1 Microbiological includes only E. coli and total coliform results.

2 Lead plumbing results were not included in chemical analysis; however, lead distribution results were included. See Table 11 for additional details about lead in plumbing.

Non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems and systems serving designated facilities

Ontario residents living in mobile home parks and other residential facilities may be serviced by non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems.

During 2012-13, 99.47 per cent of the 41,848 drinking water test results submitted by laboratories on behalf of 434 non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems met Ontario’s strict standards.

We continue to work with the owners and/or operators of these systems to inform them about their regulatory responsibilities and help them comply with the requirements of O. Reg. 170/03.

| Parameter | 2010-11 % meeting standards | 2011-12 % meeting standards | 2012-13 % meeting standards |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microbiological1 | 99.32 | 99.46 | 99.52 |

| Chemical2 | 99.56 | 99.43 | 99.34 |

| Total | 99.38 | 99.45 | 99.47 |

1 Microbiological includes only E. coli and total coliform results.

2 Lead plumbing results were not included in this chemical analysis; however, lead distribution results were included. See Table 11 for additional details about lead in plumbing.

3 Radiological parameters are tested in drinking water systems where directed by the ministry.

Some health care centres, schools and day nurseries in Ontario that have their own drinking water systems, are referred to as systems that serve designated facilities.

During 2012-13, of the 75,328 drinking water tests submitted by laboratories on behalf of 1,389 of these systems, 99.57 per cent met Ontario’s strict standards.

As shown in the following table, the percentage of test results for systems serving designated facilities that met Ontario’s standards has been consistently high over the past several years.

| Parameter | 2010-11 % meeting standards | 2011-12 % meeting standards | 2012-13 % meeting standards |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microbiological2 | 99.50 | 99.40 | 99.49 |

| Chemical | 99.31 | 99.67 | 99.67 |

| Total | 99.43 | 99.52 | 99.57 |

1 Radiological parameters are tested in drinking water systems where directed by the ministry.

2 Microbiological includes only E. coli and total coliform results.

| Parameter | Total number of test results | Total number of test results meeting standards | Total number ofadverse test results | Per cent of adverse test results | Total number of systems submitting test results1 | Total number of systems with adverse test results2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microbiological3 | 469,614 | 469,134 | 480 | 0.10 | 657 | 174 |

| Chemical4 | 62,243 | 62,095 | 148 | 0.24 | 660 | 55 |

| Radiological | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 531,859 | 531,231 | 628 | 0.12 | 661 | 212 |

| Parameter | Total number of test results | Total number of test results meeting standards | Total number ofadverse test results | Per cent of adverse test results | Total number of systems submitting test results 1 | Total number of systems with adverse test results 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microbiological3 | 30,962 | 30,812 | 150 | 0.48 | 434 | 71 |

| Chemical4 | 10,886 | 10,814 | 72 | 0.66 | 399 | 27 |

| Total | 41,848 | 41,626 | 222 | 0.53 | 434 | 93 |

| Parameter | Total number of test results | Total number of test results meeting standards | Total number ofadverse test results | Per cent of adverse test results | Total number of systems submitting test results 1 | Total number of systems with adverse test results 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microbiological3 | 43,996 | 43,773 | 223 | 0.51 | 1,369 | 125 |

| Chemical | 31,332 | 31,229 | 103 | 0.33 | 1,285 | 29 |

| Total | 75,328 | 75,002 | 326 | 0.43 | 1,389 | 150 |

1 Regulatory requirements for testing vary by category and source of water and are identified in O. Reg. 170/03.

2 A single system could have adverse test results for multiple parameters. For calculating total number of systems with adverse results, a system with adverse test results across multiple parameters is counted only once.

3 Microbiological includes only E. coli and total coliform results.

4 Lead plumbing results were not included in this chemical analysis; however, lead distribution results were included. See Table 11 for additional details about lead in plumbing.

5 Radiological parameters are tested in drinking water systems where directed by the ministry.

Adverse water quality incidents and corrective actions

Corrective action on adverse water quality incidents

As part of the safety net that protects our drinking water, the Safe Drinking Water Act requires every adverse water quality incident to be reported immediately, and corrective action to be taken.

Corrective actions vary depending on the adverse event and may include resampling and retesting and adjusting the system or treatment processes. The local medical officer of health may direct an alternate drinking water source be used and/or issue a boil water or drinking water advisory and direct system owners to issue these advisories if necessary.

An adverse water quality incident (AWQI) does not necessarily indicate that the drinking water is unsafe. An AWQI indicates that a drinking water test result has not met an Ontario Drinking Water Quality Standard, or that there is an operational problem within a drinking water system.

Under O. Reg. 170/03, the following are some of the conditions that may result in an adverse water quality incident:

- a drinking water test result exceeding the Ontario Drinking Water Quality Standards

- presence of microbiological parameters that are not listed in the Ontario Drinking Water Quality Standards in a drinking water test result

- a test result exceeding the maximum concentration of a health-related parameter as established in a municipal drinking water licence or order

- a test result indicating the presence of a pesticide, not listed in the Ontario Drinking Water Quality Standards, at any concentration

- certain operational issues occurring in a drinking water system, such as insufficient disinfection, reduction in water pressure, high turbidity, equipment problems, contamination following a heavy rainfall or other adverse weather events.

It is important to note that while an AWQI does not always mean that the drinking water is unsafe, the Safe Drinking Water Act requires taking corrective action when and where an adverse water quality incident is reported, regardless of the circumstances behind it. This is a critical component of Ontario’s drinking water safety net.

When necessary, the ministry conducts site inspections and may collect drinking water samples where issues may be suspected requiring confirmation. We will also monitor and manage all reports from system owners that document the resolutions to issues to help ensure that the adverse water quality incidents are appropriately resolved.

| Parameter | 2010-11 | 2011-12 | 2012-13 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Systems submitting test results | 681 | 671 | 661 |

| Number of Systems with AWQIs | 404 | 389 | 381 |

| Number of AWQIs | 1,562 | 1,402 | 1,446 |

| Number of Results within AWQIs1 | 1,717 | 1,603 | 1,700 |

| Parameter | 2010-11 | 2011-12 | 2012-13 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Systems submitting test results | 434 | 429 | 434 |

| Number of Systems with AWQIs | 177 | 180 | 179 |

| Number of AWQIs | 445 | 412 | 359 |

| Number of Results within AWQIs1 | 546 | 489 | 415 |

| Parameter | 2010-11 | 2011-12 | 2012-13 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Systems submitting test results | 1,457 | 1,426 | 1,389 |

| Number of Systems with AWQIs | 373 | 476 | 390 |

| Number of AWQIs | 630 | 736 | 625 |

| Number of Results within AWQIs1 | 759 | 828 | 740 |

1 An AWQI may occur as a result of a single issue or multiple issues such as the presence of microbiological or chemical parameters and/or operational issues.

Drinking water advisories and corrective actions

Drinking water advisories may be issued due to a range of factors that may affect drinking water, such as watermain breaks, low pressure events, presence of microbiological parameters, low disinfectant levels, or drinking water system compliance issues (e.g., equipment failure). The local medical officer of health may issue a boil water or drinking water advisory or require the system owner to take other corrective actions if there is a concern that the drinking water may not be fit for human consumption. The system owner may also recommend its consumers boil their water or use an alternative source as a precautionary measure.

Drinking water system owners must take corrective actions and follow any additional directions from the local health unit to rectify the incident. Ministry staff, in collaboration with local public health units and system owners and/or operators, and in some instances municipalities, monitor incidents to ensure they are resolved.

Boil water advisories that last for 12 consecutive months are considered to be long-term. In 2012-13, all pre-existing provincial long-term boil water advisories for municipal residential drinking water systems were lifted.

In 2012-13, the Lynden Drinking Water System, located near Hamilton had a long-term drinking water advisory due to the presence of lead. The affected residents were offered on-tap filters that are certified for lead removal. In addition, the system owner retained qualified consultants to undertake additional studies to identify the source(s) of lead and options to address this ongoing issue. Ministry staff will continue to work closely with the system owner and the local medical officer of health to ensure ongoing appropriate corrective actions are taken.

Please contact your local medical officer of health for more information on specific advisories.

Lead Action Plan

The most common source of lead in drinking water is lead pipes or solder used to connect the pipes and plumbing fixtures. When water wears away the inner surface of pipes, it is called corrosion. If the pipe’s inner surface contains lead, corrosion can cause lead to enter the drinking water. Through regular testing, facility owners and/or operators and ministry staff monitor the presence of lead in drinking water.

Most municipalities have ongoing programs to remove lead service lines up to the property line. It is important for homeowners to remove lead service lines on their property to reduce their exposure to lead from drinking water. For more information see the lead service line replacement article on Ontario’s website.

Our Lead Action Plan sets sampling and testing requirements that allow us to collect information about lead levels in drinking water in communities throughout Ontario.

Schools, day nurseries and regulated drinking water systems are required to collect and submit samples to laboratories for lead testing. They must report any exceedances to the ministry and take corrective action if the results indicate there is a lead issue. All schools and day nurseries are also required to regularly flush their plumbing. Flushing is effective at reducing lead levels in drinking water because it prevents water from standing in the plumbing for extended periods of time thus reducing contact time with the pipes and plumbing.

Through regular testing, facility owners, operators and ministry staff monitor the presence of lead in drinking water. Where lead levels exceed the provincial standard, owners and/or operators continue to focus on public protection by working with municipalities and the local medical officers of health to ensure appropriate corrective actions are taken. Corrective actions are recommended by the local public health unit and can include providing an alternative drinking water supply and/or filters, undertaking longer flushing periods before taking additional samples, or replacing plumbing known to contain lead solder, pipes and fixtures.

The vast majority of test results submitted on behalf of schools, day nurseries and regulated systems continue to meet the provincial standard for lead.

Lead testing results: schools and day nurseries

Under O. Reg. 243/07 all schools and day nurseries are required to regularly flush the water in their facility’s plumbing to minimize potential lead exposure in their drinking water. They also must submit two types of samples of their drinking water to a laboratory for lead testing:

- standing samples collected after the plumbing has not been used for at least six hours

- flushed samples collected 30 to 35 minutes after running taps and/or faucets for five minutes

Consistent lead test results over the past several years have shown that flushing significantly reduces lead in drinking water. In 2012-13, 96.74 per cent of flushed sample results for schools and day nurseries met the lead standard. This result is almost six per cent better than the results for standing samples.

Laboratories must report lead test results that exceed the standard for lead to the local public health unit, the system owner and/or operator and to the ministry. In these situations, ministry staff follow up with the local public health unit and the facility to ensure that all recommended corrective actions have been taken.

| Parameter | 2010-11 % meeting standards | 2011-12 % meeting standards | 2012-13 % meeting standards |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lead - Flushed | 94.56 | 95.93 | 96.74 |

| Lead - Standing | 87.58 | 89.01 | 90.79 |

| Parameter | Total number of results | Total number of lead exceedances | Total number of schools and day nurseries submitting results 1 | Total number of schools and day nurseries with lead exceedances |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lead - Flushed | 8,987 | 293 | 7,330 | 170 |

| Lead - Standing | 8,841 | 814 | 7,326 | 589 |

1 Facilities that share the same plumbing system, known as co-located facilities, may submit a single set of samples. Allowances have been made for facilities to reduce sampling frequency to every 36 months from the required annual testing, based on satisfactory test results.

Lead testing results: municipal residential drinking water systems and non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems

Under O. Reg. 170/03 all municipal residential and non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems are required to collect and submit samples to laboratories for lead testing in plumbing. The following table shows the number of lead exceedances that were reported to the ministry for these systems in 2012-13.

| Drinking water facility type1 | Parameter | Total number of test results | Total number of lead exceedances | Total number of systems submitting results2 | Total number of systems with lead exceedances |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Municipal residential systems | Lead in plumbing3 | 9,330 | 445 | 181 | 55 |

| Non-municipal year-round residential systems | Lead in plumbing3 | 1,622 | 17 | 137 | 11 |

1 Systems serving designated facilities are exempt from this requirement.

2 Regulatory requirements for testing vary by category and source of water and are identified in O. Reg. 170/03.

3 Samples taken after flushing of system.

As illustrated in the following table, test results for lead in plumbing of municipal residential drinking water systems and non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems show that year after year the vast majority of these systems consistently meet Ontario’s standards.

| Drinking water facility type1 | 2010-11 % meeting standards | 2011-12 % meeting standards | 2012-13 % meeting standards |

|---|---|---|---|

| Municipal residential systems | 95.68 | 96.96 | 95.23 |

| Non-municipal year-round residential systems | 98.62 | 98.82 | 98.95 |

1 Systems serving designated facilities are exempt from this requirement.

Corrosion control for municipal residential drinking water systems

Owners and/or operating authorities of municipal residential drinking water systems that serve more than 100 private residences must develop corrosion control plans if:

- more than 10 per cent of all plumbing location test results confirm lead concentrations greater than 10 micrograms per litre in two out of three sampling rounds

- in those two rounds, at least two sample results exceed the standard of 10 micrograms per litre for lead

These plans must be submitted to the ministry for the Director’s review and approval.

In 2012-13, no new communities were required to prepare corrosion control plans. Of the 20 communities that were included in the last two Chief Drinking Water Inspector’s reports (2010-2011 and 2011-2012) significant progress is being made:

- eleven communities have submitted their plans and are currently implementing them.

- six communities are pursuing alternative lead control strategies such as replacing lead service lines.

- the City of Sault Ste. Marie’s corrosion control plan is on hold as the city is evaluating additional actions and/or upgrades to their water treatment processes and system.

- the City of Brantford and the Town of Arnprior are working towards modifying their treatment process, which would improve the quality of their drinking water. When the modifications are completed, these communities will be required to carry out two full rounds of community lead sampling. If lead exceedances are still present, corrosion control plans will be prepared.

Inspecting drinking water systems

Municipal residential drinking water systems

Ministry staff inspect all municipal residential drinking water systems at least once a year to ensure compliance with Ontario’s strict regulatory requirements.

The Compliance and Enforcement Regulation (O. Reg. 242/05) legislates annual inspections of all municipal residential drinking water systems, with one out of every three inspections being unannounced. The ministry inspects these systems using a proactive, risk-based compliance approach.

The ministry provides inspection reports to municipal residential drinking water system owners and/or operating authorities within 45 days of completing inspections, and these reports must be made publicly available by municipalities. If inspectors identify non-compliance issues at a system, the ministry may take actions such as:

- identifying suggestions to address areas of non-compliance in the inspection report

- discussing crucial inspection findings with the owner and/or operator

- providing the inspection report to other affected parties, including the local medical officer of health and the local conservation authority

- providing education and outreach on issues that are not directly related to drinking water safety, such as administrative non-compliance issues

- issuing a provincial officer’s order that requires the system owner and/or operator to take corrective action by a specific deadline

- referring the incident to the ministry’s Investigations and Enforcement Branch

Inspection results

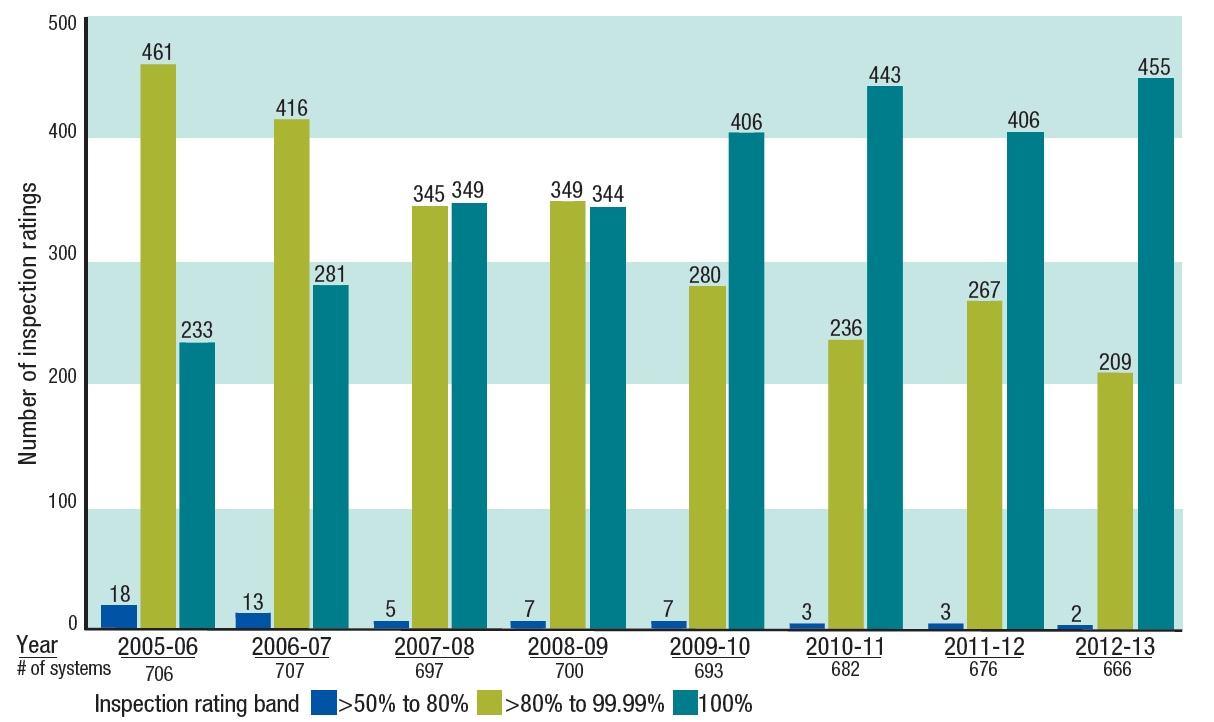

In 2012-13, 455 of 6662 (or 68 per cent) of municipal residential drinking water systems that were inspected yielded inspection ratings of 100 per cent — an increase of eight per cent compared to the 2011-12 results. Of the total number of systems, 99.7 per cent achieved inspection ratings greater than 80 per cent.

Figure 3: Year-over-year comparison of municipal residential drinking water system inspection ratings1

1 The decline in the total number of municipal residential drinking water systems is due to amalgamations of these systems.

The quality of drinking water and the proper maintenance and operation of these systems are a priority for the ministry. We continue to work with the owners and/or operators of systems with inspection ratings below 100 per cent to assess their regulatory requirements and improve the performance of their systems.

After analysing inspection program results for 2012-13, we identified the following trends in non-compliance and areas that require special attention and improvement ensuring that:

- continuous monitoring equipment is performing tests properly

- all equipment is installed in accordance with the requirements of the system’s drinking water works permit

- operating treatment equipment is working properly (e.g., ultraviolet radiation equipment, correct dosage of chlorine is used, etc.)

- secondary disinfection is maintained (e.g., ensuring chlorine residuals do not drop below the required levels)

All drinking water system owners and/or operators have the opportunity to meet with the local water supervisor to discuss any concerns related to their compliance inspection and rating reports.

Deficiencies

In 2012-13, no deficiencies were identified at any municipal residential drinking water systems.

A deficiency is a violation of specified provisions of the Safe Drinking Water Act and its regulations that, in the opinion of the Director, could pose a drinking water health hazard. For example, water treatment equipment that is not operating according to provincial standards may impact the quality of drinking water and adversely affect the health of those using the system. Under the act, the system owner and/or operator must take mandatory action within 14 days of an inspector confirming a deficiency at a municipal residential drinking water system.

Orders and order resolutions

To resolve non-compliance issues at a drinking water system, our inspectors may issue a contravention order and/or preventative measures order to the system owner and/or operator.

In 2012-13, we issued nine orders to nine municipal residential drinking water systems:

- two contravention orders were issued to two municipal residential drinking water systems as a result of inspections. The orders addressed issues such as a failure to record the flow monitoring data correctly and immediately notify the consumers and the local medical officer of health of the loss of disinfection.

- six preventative measures orders and one contravention order were issued to seven municipal residential drinking water systems as a result of incidents identified outside of an inspection. Some requirements of the orders included removing the end of the watermain from the sewer manhole and having a qualified person survey the water distribution system for additional cross-connections.

Seven systems have complied with the requirements of their orders. The two remaining systems continue to make progress and work towards meeting regulatory requirements. See the Appendices for more details on these nine systems.

When potential violations of Ontario’s environmental laws such as the Safe Drinking Water Act occur, ministry inspectors may refer violations to the ministry’s Investigations and Enforcement Branch for follow-up action.

| Systems with inspection-related orders | 2010-11 | 2011-12 | 2012-13 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of inspections of municipal residential drinking water systems | 682 | 676 | 666 |

| Total number of municipal residential drinking water systems with inspection-related orders1 | 5 | 6 | 2 |

| Systems with non-inspection-related orders2 | 4 | 1 | 7 |

| Total number of orders issued to municipal residential drinking water systems (inspection and non-inspection) | 9 | 7 | 9 |

1 In 2010-11, three municipal residential drinking water systems were issued preventative measures orders during their inspections.

2 Non-inspection-related orders are issued as a result of an issue at a drinking water system that occurred outside of the context of a scheduled inspection.

Non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems and systems serving designated facilities

The ministry conducts proactive, risk-based inspections of non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems and systems serving designated facilities. When considering which systems to inspect, the ministry assesses compliance history, number and reasons for adverse water quality incidents and recommendations made by local public health units.

When necessary, ministry staff work with the owners and/or operators of non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems and those serving designated facilities to address non-compliance issues and to help them understand their regulatory requirements.

Inspection results and orders

In 2012-13, the ministry inspected 135 of 4583 registered non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems and issued 10 contravention orders.

Also during this period, the ministry inspected 488 of 1,5254 registered systems serving designated facilities. Ten contravention orders and one preventative measures order were issued to system owners as a result of these inspections or in response to adverse water quality incidents.

Examples of issues described in the orders include failure to operate a drinking water system with a certified operator, failure to meet minimum treatment requirements, and failure to sample raw water for microbiological parameters according to legislation.

To help these owners and/or operators better understand their legal obligations, we have a range of educational materials including instructional videos and easy-to-follow guides available on the Drinking Water section on Ontario’s website.

Local services boards

Local services boards operate drinking water systems in northern communities that do not have municipal government structures. These systems are classified as non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems, but are inspected using a detailed municipal inspection protocol.

Inspection results and orders

In 2012-13, ministry staff inspected all seven drinking water systems operated by local services boards and no orders were issued as a result of these inspections. One local services board, that received orders in 2005-06 and 2006-07, is constructing and installing a treatment system designed to meet all disinfection requirements as identified in the orders.

Schools and day nurseries

Whether they are connected to municipal residential drinking water systems or not, we conduct risk-based inspections of schools and day nurseries to minimize potential lead exposure of school children from pipes and plumbing. In 2012-13, the ministry conducted 883 inspections of 11,082 registered schools and day nurseries.

Several years of testing for lead in drinking water indicates that more than 80 per cent of Ontario schools and day nurseries regulated under O. Reg. 243/07 do not have issues of excess lead in their drinking water and for those that do, appropriate flushing remains part of their routine.

As a result, in August 2012, we established a risk-based compliance strategy focussing resources on the areas of highest risk. To supplement the inspection program, over 10,000 owners and operators of schools and day nurseries were asked to complete and submit an online report to the ministry. The information provides us with valuable profile and compliance information and allows us to take a risk-based approach when targeting schools and day nurseries for inspection. It also helps us determine which facilities need further education and guidance to ensure they fulfil their regulatory requirements.

Risk-based compliance audits

In 2012-13, the ministry introduced a new component to its O. Reg. 243/07 compliance program in the form of a "compliance audit". The compliance audit is a review to validate information contained in forms that are submitted to the ministry by owners and/or operators of schools and day nurseries in Ontario. The audit was designed and implemented as an additional compliance check to verify information submitted to the ministry outside of the regular inspection program.

During this time, we conducted 946 compliance audits of the registered schools and day nurseries. No orders were issued as a result of inspections and audits completed during the reporting period.

Schools and day nurseries may be eligible for a reduced flushing and lead testing schedule if they meet certain criteria. If the results of the compliance audit indicated that a facility did not fulfill these criteria, the ministry issued a letter instructing the operator to return to an annual lead sampling and testing schedule until the criteria are met.

Inspecting laboratories that test Ontario’s drinking water

Safeguarding Ontario’s drinking water includes regular testing and inspections of the laboratories that test Ontario drinking water samples. Laboratories within the province that perform testing of Ontario drinking water must be appropriately accredited, inspected at least twice per year and licensed by the ministry. Eligible laboratories located outside the province must be appropriately accredited and posted on the ministry’s Eligibility List, and are inspected at least twice per year. In 2012-13, there were two eligible laboratories on the Eligibility List.

Before the ministry issues a drinking water testing licence to a laboratory, or adds a laboratory to the Eligibility List, the laboratory must meet certain requirements of the Safe Drinking Water Act, such as:

- ability to analyse Ontario’s drinking water at prescribed low-level detection limits

- using and applying only ministry-approved referenced analytical methods

- using and applying instrumentation designed to analyse specific parameters in drinking water

- documenting policies and procedures pertaining to the laboratory’s regulatory requirements

An important cornerstone of Ontario’s multi-barrier approach to safeguard our drinking water is inspecting all 54 laboratories that analyse Ontario’s drinking water. Laboratory inspections are necessary to ensure they are operating according to provincial regulations.

Laboratories are inspected at least twice each year, with one of these inspections being unannounced. Ministry staff may also perform inspections if complaints of suspicious test results are received or if non-licensed facilities are found analysing drinking water samples.

| Inspection type | Laboratory inspections | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2010-11 | 2011-12 | 2012-13 | |

| Announced | 53 | 51 | 53 |

| Unannounced | 521 | 522 | 53 |

| Other3 | 1 | 24 | 2 |

| Total | 106 | 105 | 108 |

| Number of laboratories inspected | 53 | 53 | 545 |

1 During 2010-11, one laboratory voluntarily withdrew from the licensing program between its announced and unannounced inspections.

2 During 2011-12, one out-of-province laboratory joined the program in progress and received one unannounced inspection.

3 Other inspections included laboratory pre-licensing or relocation inspections.

4 During 2011-12, of the two laboratories that received pre-licensing inspections, one did not receive any other inspection as it was granted its drinking water testing licence less than three months before the fiscal year ended.

5 During 2012-13, one laboratory that joined the licensing program in the second half of the fiscal year was not inspected; another laboratory voluntarily withdrew its licence in the second half and was not inspected.

We provide laboratories an inspection report within 45 days of completing the inspection. Drinking water testing methods, sample handling, management practices, and reporting of adverse water quality incidents are just some of the areas covered during an inspection.

In 2012-13, two contravention orders were issued to one licensed laboratory and one non-licensed facility. The licensed laboratory has complied with the requirements of their order. The non-compliance issues of the non-licensed facility have been referred to the ministry’s Investigations and Enforcement Branch for follow up.

| Parameter | 2010-11 | 2011-12 | 2012-13 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of licensed laboratories that received inspection-related orders | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Number of licensed laboratories that received non-inspection-related orders | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Number of non-licensed facilities that received non-inspection-related orders | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Total number of orders issued to licensed laboratories and non-licensed facilities (inspection and non-inspection) | 1 | 0 | 2 |

While inspection results show that laboratories that test Ontario’s drinking water continue to perform well, we identified the following areas for improvement:

- development of a policy/procedure to notify impacted drinking water system owners and/or operators that an order or decision was given to suspend/revoke the accreditation of the laboratory

- creation of a policy/procedure to ensure that samples related to drinking water are not filtered before they are analysed

- ensuring that reported results to the system owner are routinely validated to confirm they are the same as those that are submitted electronically to the ministry’s Drinking Water Information System and/or Laboratory Results Management Application databases

- maintenance of records and procedures for the calculation of aggregate parameters such as total trihalomethanes

Compliance and enforcement: enforcement results

Ontario’s environmental protection legislation protects communities and the environment. Breaking the law can result in serious penalties.

The Compliance and Enforcement Regulation (O. Reg. 242/05) of the Safe Drinking Water Act requires the Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change to fulfill a number of specific activities such as taking mandatory actions and conducting inspections of municipal residential drinking water systems and laboratories that test Ontario’s drinking water.

The table below summarizes the ministry’s compliance and enforcement activities for 2012-13.

| Municipal residential drinking water systems | Laboratories that test Ontario’s drinking water |

|---|---|

|

|

In addition to providing a framework for inspection and compliance activities, the Compliance and Enforcement Regulation also provides the public with the right to request an investigation of an alleged contravention of the Safe Drinking Water Act or any of its regulations or instruments. In 2012-13, the ministry did not receive any such requests.

Convictions: conviction results

We continue to work with our drinking water partners on many fronts to address areas of non-compliance. Our inspectors may refer violations of Ontario’s environmental laws, such as the Safe Drinking Water Act, to the ministry’s Investigations and Enforcement Branch (the Branch) for follow up and investigation if warranted. The Branch works with Crown Counsel to determine whether to proceed with a prosecution.

For 2012-13, there were 14 convictions of municipal residential and non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems, systems serving designated facilities as well as schools and day nurseries which resulted in fines totalling $300,900.

| Facility type | Number of facilities | Total number of cases with convictions1 | Fines |

|---|---|---|---|

| Municipal residential drinking water systems2 | 3 | 3 | $186,500 |

| Non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems3 | 6 | 6 | $55,000 |

| Systems serving designated facilities3 | 3 | 3 | $17,900 |

| Schools and day nurseries3 | 2 | 2 | $41,500 |

| Licensed laboratories | 0 | 0 | |

| Total | 14 | 14 | $300,900 |

1 A case may involve one or more charges.

2 For further details, please see Appendix 3.

3 Includes convictions against legal entities and individuals.

Convictions - Municipal residential drinking water systems

- The Corporation of the Municipality of West Elgin and three of its water distribution system operators were fined for drinking water violations including providing false information and failing to report adverse test results. Ministry staff inspected and found that the minimum level of chlorine had not been maintained in the drinking water distribution system, log books had been altered and false information had been provided to the ministry. In addition, the operators did not report occurrences to the ministry or the local medical officer of health when chlorine levels in the distribution system were below the minimum level. One operator was sentenced to 30 days in jail and ordered to surrender his certificate to operate a drinking water system and not to work at or operate any business or employment concerning or related to drinking water.

- The Corporation of the Municipality of North Middlesex and two of its operators were fined. Ministry staff inspected the drinking water distribution system and found that the two system operators were operating with expired certificates. The municipality was also responsible for failing to collect a sample following watermain repairs.

- PUC Services Inc., an operating authority responsible for the Blind River drinking water system and providing disinfection of raw water on behalf of the Town of Blind River, failed to immediately report the results of the filtered water quality tests indicating that raw water from the drinking water system was not properly disinfected. Data submitted by the company showed that filtered water quality tests did not meet the criteria for disinfection of raw water.

Training drinking water system professionals

The strength of Ontario’s drinking water safety net relies on the skills, experience and performance of those individuals who are responsible for operating our regulated systems. Ontario’s drinking water operators are among the best trained in the world, thanks to our stringent certification and training requirements. Operators are required to go through rigorous training, write examinations, and meet mandatory continuing education requirements to renew and maintain their certification.

Operator certification requirements

To be certified, all municipal drinking water operators in Ontario must meet education, training, experience and examination requirements.

In Ontario, a new operator starts as an operator-in-training. Operators-in-training must meet experience requirements and write an examination to become certified for each type of system. A drinking water operator-in-training is also required to complete the ministry’s entry-level drinking water operator training course to qualify for higher drinking water certificates.

To help promote careers in the water and wastewater industry, the ministry has agreements with 16 community colleges that offer the mandatory entry-level drinking water operator training course as part of their environmental and engineering programs.

As of December 31, 2013, 1,137 students received the entry-level drinking water operator course certificate. Of these, approximately 27 per cent hold a valid drinking water operator certificate.

Once certified, drinking water operators in Ontario must be trained according to the type and class of facility they operate. The more complex a system is (the higher the class of system), the more training an operator must complete.

If an operator works in more than one type of drinking water system, he or she may hold multiple certificates.

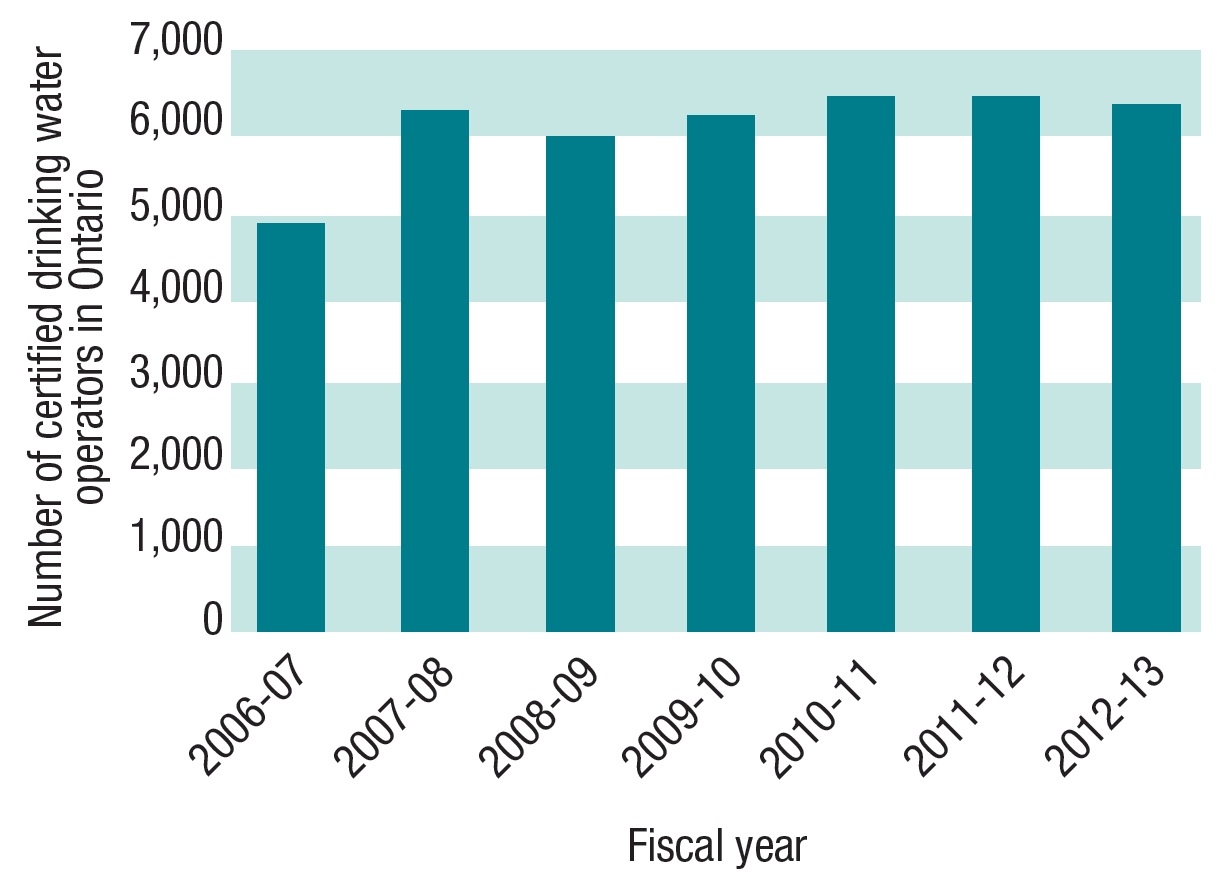

Statistics on drinking water operators in Ontario

In 2012-13, 719 new operators received 1,231 new operator-in-training certificates. Of these, eight operator-in-training certificates were issued to seven new First Nations operators 5.

As of March 31, 2013, 6,340 operators held a total of 8,775 certificates. Of these, 135 were employed as First Nations system operators across the province and held a total of 205 drinking water operator certificates

Figure 4: Number of certified drinking water operators in Ontario

Operator training and the Walkerton Clean Water Centre

The Walkerton Clean Water Centre (the Centre) is one of the educational institutions in Ontario that offers operator training programs. The Centre is a state-of-the-art facility providing high-quality hands-on training, classroom training and technology demonstrations.

In addition to delivering the Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change’s mandatory courses, the Centre also delivers province-wide training, with a focus on small and remote drinking water systems, including those serving First Nations. In 2012-13, the Centre presented a small systems workshop, in cooperation with the Ontario Water Works Association, to small drinking water system owners, operators and operating authorities.

To further enhance opportunities for hands-on, province- wide training, the Centre offers regional maintenance events across the province. Maintenancefest is an annual training experience during which participants cycle through several two-hour hands-on training modules and topics that are specific to the operation and maintenance of drinking water systems.

As of March 31, 2014, the Centre has trained more than 48,580 new and existing professionals since it opened in 2004.

Disciplinary actions

Holding a drinking water certificate grants operators a right to operate in Ontario. With this right comes a responsibility. Operators are expected to follow all applicable laws and to act honestly, competently and with integrity with a view to the public’s protection.

If an operator fails to meet these requirements, the ministry is authorized to take disciplinary action. While instances of unethical behaviour tend to be rare, disciplinary actions are necessary to help ensure that public health is protected, and that the integrity of the operator certification program is maintained.

The following table provides details about the disciplinary actions the ministry took against one operator in 2012-13.

| Reason | Action taken |

|---|---|

| Operator removed exam materials from the examination room during a certification exam. |

|

Small drinking water systems program results: Ministry of Health And Long-Term Care

Message from the Chief Medical Officer of Health

The Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care continues to share a strong commitment to excellence with the Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change by supporting health units and communities to provide safe drinking water in the province.

Since the 2008 transfer of oversight for small drinking water systems to the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, we have moved the yardstick for safeguarding Ontario’s drinking water. Through the successful implementation of the Small Drinking Water Systems Program, local public health units have conducted detailed inspections and risk assessments on existing small drinking water systems across Ontario, and those operators each have a system-specific plan to keep their drinking water safe. This customized approach, rather than a one-size-fits-all program, addressed the Ontario Drinking Water Advisory Council’s recommendation for a better way to provide safe drinking water from small systems without compromising provincial drinking water standards.

The Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care and local public health units also provide support and input to the Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change on a range of other drinking water initiatives including adverse drinking water incident response and provincial drinking water quality standards applicable to all systems. This ongoing collaboration and exchange of information and advice to protect public health further fortifies Ontario’s drinking water safety net.

The success of the Small Drinking Water Systems Program is now being realized through the identification of and corrective actions taken to reduce adverse water quality incidents in systems that were not previously inspected. Achieving this milestone in drinking water protection was made possible through effective partnerships with provincial and local public health officials.

I want to take this opportunity to thank the local boards of health and all of our partners for their ongoing efforts and leadership to protect the health and safety of all people of Ontario.

Dr. Arlene King, MD, MHSc, FRCPC

Chief Medical Officer of Health6

Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care

The information in the Small Drinking Water Program Results section was provided by the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. For more information, please visit the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care website.

Risk assessments

Small drinking water systems are generally stand-alone systems that supply drinking water at public facilities that do not get their drinking water from a municipal residential drinking water system. The majority of these facilities are located outside of major metropolitan areas and may include community centres, motels, restaurants, seasonal camps, places of worship and bed and breakfasts.

As of March 31, 2013, there were 11,221 small drinking water systems in Ontario. The number of systems can fluctuate as some systems are decommissioned and new systems are built or come into use.

The Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care’s Small Drinking Water Systems Program is regulated under the Health Protection and Promotion Act and its regulations, and is administered by local boards of health (public health units). Public health inspectors conduct risk assessments of small drinking water systems in the province to determine what owners and/or operators must do to keep their drinking water safe. The small drinking water system owner receives a legally binding directive that applies to that system, which may include requirements for water sampling, water treatment options, operational checks, and owner and/or operator training.

The risk assessment process involves visiting each small drinking water system to identify and assess risks that may affect the quality of the water produced. Public health inspectors use a web-based application — Risk Categorization Assessment Tool — to conduct the risk assessment. The assessment includes visual inspections of the water source, system equipment and components, and an evaluation of documentation relating to the system’s water testing and historical sampling results. These factors are then taken into consideration in establishing the sampling requirements for a given small drinking water system and determining the level of risk (low, moderate or high).

As of March 31, 2013, 96 per cent7 of the Small Drinking Water Systems Program has been implemented. A total of 10,755 risk assessments have been finalized and 466 are in progress.

| Risk assessments | As of March 31, 2012 | As of March 31, 2013 |

|---|---|---|

| Finalized | 7,633 | 10,755 |

| In progress | 1,885 | 466 |

| Categories of finalized risk assessments | As of March 31, 2012 | As of March 31, 2013 |

|---|---|---|

| High | 1,362 (17.84%) | 1,789 (16.63%) |

| Moderate | 1,341 (17.57%) | 1,708 (15.88%) |

| Low | 4,930 (64.59%) | 7,258 (67.48%) |

The Small Drinking Water Systems Program reflects a risk-based approach for each small drinking water system depending on the level of risk. Risk category is determined by grading factors that are applied to results of a drinking water source and treatment components questionnaire, as well as a distribution component questionnaire. To help ensure that small drinking water systems are providing safe drinking water, systems categorized as "high risk" are monitored through more frequent sampling and testing, and are required to be re-inspected every two years. While moderate and low risk systems are also monitored through routine sampling and re-inspections, drinking water is sampled and tested at a lower frequency and these systems are re- inspected every four years.

Adverse water quality incidents for small drinking water systems

Small drinking water system operators are required to sample their water supplies for the presence of indicator bacteria (total coliform and E. coli) at a frequency outlined in the directive or as set out in regulations. Adverse water quality incidents (AWQIs) can result from an observation (e.g., an observation of treatment malfunction) or an adverse test result.

As the primary contaminant of concern for small drinking water system water is bacteria, small drinking water systems are required to routinely test for microbiological indicator organisms such as total coliform and E. coli. Testing for other contaminants such as chemicals (e.g., nitrates) is only required where the risk assessment and resulting directive determines that other possible contaminants could potentially pose a risk. For example, a small drinking water system that is located near an agricultural or industrial setting may be required to test for additional parameters. Since over 99 per cent of water samples are tested for bacterial contaminants, it is not surprising that the majority of adverse test results reported are microbiological.

Detection of these indicator organisms triggers an adverse water quality response such as notification of users. Further follow-up is immediately taken to determine if the water poses a risk to health if consumed or used. Additional action is also taken as required. In other words, an adverse test result does not mean that users are at risk of becoming sick because immediate precautions are taken based on the initial test result and drinking water advisories are issued where appropriate.

A Small Drinking Water Information System supports the program and has two applications: a Risk Categorization Assessment Tool and a Laboratory Result Management System Application.

The Laboratory Result Management System is used for review of small drinking water systems’ sampling compliance, test results and AWQIs. This system, together with the Risk Categorization Assessment Tool, is also used for monitoring the program’s implementation. Regular sampling of drinking water systems is performed by operators who then submit the water samples to laboratories for testing. These results are recorded in the Laboratory Result Management System.

In the event of an adverse test result, the laboratory will notify both the owner and/or operator of the small drinking water system and the local public health unit for immediate response to the incident. Details of the AWQI will also be tracked in the Laboratory Result Management System.

For the reporting period of April 1, 2012 to March 31, 2013, 1,173 or about 10 per cent of 11,221 small drinking water systems reported adverse water quality incidents. This number may remain steady or increase initially, as owners and/or operators continue to comply with sampling requirements in accordance with their directive and institute improvements in their drinking water system. Our adverse water quality incidents data demonstrates the success and value of the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care’s Small Drinking Water Systems Program because adverse incidents are now being systematically captured and appropriate action is taken and tracked to help protect drinking water users.

In 2012-13, 98.78 per cent of test results submitted by laboratories on behalf of small drinking water systems met the provincial standards.

During the period between April 1, 2012 and March 31, 2013, 1,173 small drinking water systems reported a total of 1,316 adverse test results (from a total of 107,755 sample results). These systems also reported 155 adverse water quality incidents identified through other means such as observation of treatment malfunction.

Through the Small Drinking Water Systems Program more operators know how to determine when their water may not be safe to drink and are working closely with public health units to take appropriate corrective actions to protect drinking water users.

| Parameter type | Total number of test results | Total number of test results meeting standards | Total number of adverse test results | 2012-13 % meeting standards |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microbiological | 106,894 | 105,662 | 1,232 | 98.85% |

| Chemical/Inorganic | 648 | 564 | 84 | 87.04% |

| Organic | 213 | 213 | 0 | 100.00% |

| Total | 107,755 | 106,439 | 1,316 | 98.78% |

Response to adverse water quality incidents for small drinking water systems

When an AWQI is detected through an observation or an adverse sample result, the owner and/or operator of the small drinking water system is required to notify the local medical officer of health and to follow up with any instruction that may be issued by a public health inspector or medical officer of health. The local public health unit will perform a risk analysis and take appropriate action to inform and protect the public.

Response to an AWQI may include issuing a drinking water advisory that will notify potential users whether the water is safe to use and drink or if it requires boiling to render it safe for use. The local public health unit may also provide the owners and/or operators of a drinking water system with instructions on necessary corrective action(s) to be taken on the affected drinking water system to mitigate the risk.

To help minimize the occurrence of AWQIs, the Small Drinking Water Systems Program takes a comprehensive and proactive approach to helping protect water that comes from small systems. Local public health units provide information to owners and/or operators on:

- how to protect their drinking water at the source by identifying possible contaminants

- how and when to test their water

- treatment options and maintenance of treatment equipment, where necessary

- when and how to notify the public, whether it is a poor water sample test result or equipment that is not working properly

- what actions need to be taken to mitigate a problem

Throughout Ontario, small drinking water system owners and/or operators are working closely with public health inspectors to follow their directives which contain their system-specific plan to protect drinking water users. The Small Drinking Water Systems Program addresses the recommendations from Ontario’s Drinking Water Advisory Council to provide safe drinking water from small systems that meets provincial drinking water standards.

Glossary

- Boil water advisory

- Notice issued by local medical officer of health to advise the community to boil or disinfect water before consumption.

- Conservation authorities

- Local watershed management agencies that deliver services and programs that protect and manage water and other natural resources in partnership with government, landowners and other organizations (Conservation Ontario).

- Contravention order

- An order a provincial officer may issue under section 105 of the Safe Drinking Water Act if the provincial officer reasonably believes a person is contravening or has contravened a provision of the act or its regulations, an order issued under the act, or a condition in a certificate, permit, licence or approval issued under the act. It may require the ordered party to comply with any directions set out in the order within the time specified.

- Director