2022-2023 Chief Drinking Water Inspector annual report

Learn about the performance of our regulated drinking water systems and laboratories, drinking water test results, and enforcement activities and programs.

Message from the Chief Drinking Water Inspector

I am pleased to present the 2022-23 Chief Drinking Water Inspector’s Annual Report which continues to demonstrate the progress that the province and our many partners are making together to safeguard Ontario’s drinking water.

The provision of safe drinking water and protection of human health remain a priority for the Ontario government. From our source protection initiatives to our rigorous inspection program and active engagement with stakeholders, we continue our work to provide the highest quality drinking water to the people of Ontario.

In this report you will find information on the performance of Ontario’s regulated drinking water systems and laboratories, a summary of drinking water test results, and the ministry’s inspection and enforcement activities. The Drinking Water Quality and Enforcement page of the Ontario Data Catalogue provides more detailed information on these items for 2022-23.

I would like to thank my colleague Dr. Kieran Moore, Chief Medical Officer of Health, for providing updates on the performance of small drinking water systems regulated by the Ministry of Health in this report.

We will continue our efforts to uphold Ontario’s high drinking water standards so that future generations also have access to clean, safe drinking water.

Steven Carrasco

Chief Drinking Water Inspector

Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks

Message from the Chief Medical Officer of Health

With the release of the 2022-23 results, Ontario’s Small Drinking Water Systems Program continues to demonstrate its value in providing Ontarians with access to clean, safe drinking water.

This program, overseen by the Ministry of Health and administered by local boards of health, includes vigilant inspections and risk assessments of all small drinking water systems in Ontario and provides the owners and operators with tailored, site-specific plans to help maintain the highest water quality possible.

This year, I am pleased to report that 98 per cent of drinking water test results met Ontario’s strict and unwavering water quality standards.

I am also proud to report that over the last decade, a significant downward trend in both total adverse water quality incidents and the number of systems that reported an adverse water quality incident has been observed.

These achievements emanate from the collaborative and dedicated work of our local boards of health, public health inspectors and our drinking water partners, who are helping to protect the health and safety of all Ontarians.

Kieran Moore

Chief Medical Officer of Health

Ministry of Health

2022-2023 at-a-glance

Statistics

In 2022-2023

- 99.9% of the more than 500,000 drinking water test results from municipal residential drinking water systems met Ontario’s drinking water quality standards

- 99.6% of more than 40,000 results from non-municipal year-round residential systems met the standards

- 99.7% of almost 60,000 results from systems serving designated facilities (such as child care centres and long-term care homes) met the standards

- 97% of the over 27,000 test results met Ontario’s standard for lead in drinking water at schools and child care centres. When looking at flushed samples only, this number increases to 98%

- Staff at licensed laboratories analyzed and reported over 1,000,000 drinking water test results

- All licensed laboratories and 99.8% municipal residential drinking water systems received a compliance rating above 80%

- 7,411 operators were certified to run drinking water systems and 1,822 operator certificates were renewed

Drinking water protection framework

Figure 1: Drinking water protection framework

The 8 components of the framework are:

- source-to-tap focus

- strong laws and regulations

- health-based standards for drinking water

- regular and reliable testing

- swift, strong action on adverse water quality incidents

- a multi-faceted compliance improvement toolkit

- mandatory licensing, operator certification and training requirements

- partnership, transparency and public engagement

- all the components work together to protect Ontario's drinking water

The drinking water protection framework aims to keep drinking water safe through multiple protective barriers and checks and balances. Examples of these include:

- source protection plans

- strong legislation

- stringent health-based drinking water quality standards

- frequent operational checks and water monitoring

- duplicative reporting

- highly trained and licensed operators with continuing education requirements

- regular inspections of drinking water systems and licensed laboratories

- partnership, transparency and public engagement

The continued success of the drinking water protection framework is the result of continuous collaboration between our many partners, including municipalities, system owners and operators, local health units, laboratories, the Walkerton Clean Water Centre and stakeholder associations. The framework comprises multiple checks and balances to safeguard Ontario’s drinking water. These oversight measures mean there are precautions in place at every step of the process to prevent or address risks to the quality of our drinking water.

A key component of the framework is the mandatory licensing of both municipal residential drinking water systems and of the laboratories that test Ontario’s drinking water. The ministry requires licensing of municipal drinking water systems to confirm that these are designed in accordance with regulatory requirements, while the licensing of a laboratory authorizes which parameters the laboratory can test for in Ontario drinking water.

The licensing program mandates that the licence for all municipal residential drinking water systems be reviewed at least once every 5 years. The next renewal cycle begins in 2024 and will see all municipal drinking water licences updated and renewed by 2028.

To obtain or renew a municipal drinking water licence, the ministry requires the owner to have the following in place for their drinking water system(s):

- a Drinking Water Works Permit to establish or alter a drinking water system

- an accepted Operational Plan that is based on the Drinking Water Quality Management Standard

- an accredited operating authority

- a Financial Plan

- a valid Permit to Take Water

A laboratory can carry out the analysis of drinking water tests by using authorized analytical methods listed on their drinking water testing licence, which is reviewed and renewed every 5 years. To obtain or renew a drinking water testing licence, the ministry requires the laboratory owner to have the following in place:

- accreditation to ISO/IEC 17025 International Standard for testing and calibration laboratories

- testing methods that are suitable for drinking water analysis

- protocols related to sample handling, traceability of samples and reporting results

Update on ministry actions to protect drinking water

Procedure for Corrective Action for Systems Not Currently Using Chlorine

The Procedure for corrective action for drinking water systems not currently using chlorine must be followed by owners and operators, when applicable to their drinking water system, as it is part of Schedule 18: Corrective Action of Ontario Regulation 170/03 under the Safe Drinking Water Act, 2002, which prescribes corrective actions for adverse water quality incidents in specified categories of drinking water systems. Specifically, the procedure sets out the steps that owners and operators must take to address adverse microbiological test results from drinking water systems that use a method other than chlorine to disinfect the water. The procedure was extensively reviewed and refreshed by the ministry. The proposed updates to the procedure were posted for public comment on the Environmental Registry of Ontario. The ministry reviewed comments and made adjustments to the procedure based on feedback provided. While the procedure’s requirements did not change, the document was updated to:

- simplify language to make the procedure easier to read and follow for drinking water system owners and operators

- eliminate repetition and outline a clear step-by-step process to reduce user confusion

- add diagrams to provide better guidance to drinking water system owner and operators

Moving forward

The government and our partners continue to work together to improve drinking water protection and compliance. The ministry is also continuing to modernize our programs and keep pace with current information and technology. Current initiatives include:

Updating the Ministry’s Protocol of Accepted Methods and Sampling Document

The ministry is updating 2 key drinking water documents: the Protocol of Accepted Drinking Water Testing Methods; and the Practices for the Collection and Handling of Drinking Water Samples. These documents are used by the regulated community and ministry staff in the collection and analysis of drinking water samples in Ontario. The Protocol of Accepted Drinking Water Testing Methods lists analytical methods that are suitable for use by a licensed laboratory to test for all the regulated parameters in Ontario Regulation 169/03. It is also used by ministry staff to approve drinking water testing licence applications and verify compliance with testing methods during inspections. The Collection and Handling of Drinking Water Samples promotes proper sampling techniques to ensure results reflect the actual conditions of the drinking water being tested. The proposed updates to each document were posted for public comment on the ERO on December 12th, 2023.

Drinking Water Operator Project

The Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks is leading a multi-stakeholder project to assess challenges and identify measures needed to help ensure that every Ontario region has a sufficient and qualified workforce for the water and wastewater sector. Based on information collected through the project, the ministry will develop a comprehensive strategy intended to support water operator workforce recruitment and retention.

Drinking water performance

The Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks regulates the various kinds of drinking water systems and related activities set out in the Safe Drinking Water Act, 2002, including:

- Municipal residential drinking water systems that are owned by municipalities and supply drinking water to homes and businesses.

- Non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems that are privately owned and supply drinking water all year to people’s homes in places such as trailer parks, apartments, and condominium and townhouse developments where there are 6 or more private residences. This also includes drinking water systems owned by local services boards, which are volunteer organizations that are set up in rural areas where there is no municipal structure.

- Public and privately owned systems serving designated facilities that have their own source of water and provide drinking water to facilities such as children’s camps, schools, health care centres and senior care homes.

- Licensed laboratories that perform testing of drinking water.

- Certification and training for water operators and water quality analysts in Ontario.

The ministry has a comprehensive compliance program, which includes inspecting drinking water systems and laboratories, managing drinking water related incidents such as adverse water quality incidents, and outreach and education measures.

Inspections of drinking water systems focus on water source, treatment, and distribution components as well as management practices. Inspections of laboratories focus on chain of custody (the path of a sample from the time it is collected to when it is accepted by the laboratory), reporting results, sample handling, subcontracting and management practices. During an inspection, the inspector may tour the facility, interview personnel, review records, collect samples or request records, among other things. All drinking water systems and laboratory owners are issued a report with the inspector’s findings including any instances of non-compliance.

When non-compliance is identified, the inspector works with system or laboratory owners to bring them into compliance. For more serious instances of non-compliance, the inspector may issue an order or refer the matter to the ministry’s Environmental Investigations and Enforcement Branch for potential investigation.

The decision to refer non-compliant behaviour for investigation depends on several criteria, including:

- the potential impact of the non-compliance to the health of the users of the system

- the compliance history of the inspected system owner and/or operator

- the level of the owner’s cooperation

- what steps the owner and/or operator has taken or is taking to resolve the issue

The Compliance and Enforcement Regulation (Ontario Regulation 242/05 made under the Safe Drinking Water Act, 2002 also requires that the ministry take mandatory action (for example, issue an order or refer the matter for potential investigation) when a violation may compromise the safety of the drinking water. This is further detailed in the Compliance and Enforcement section below.

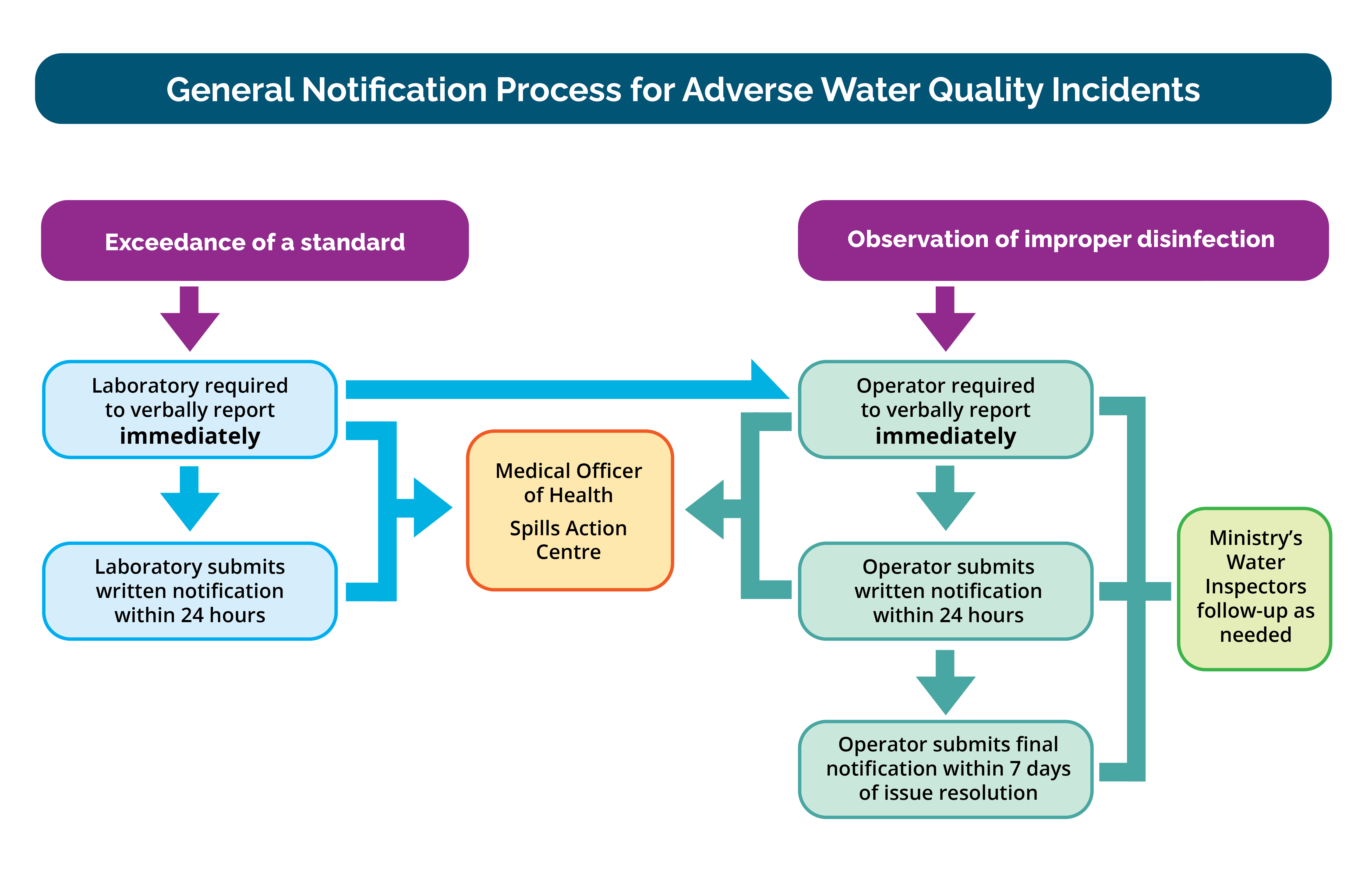

Regular monitoring and sampling at drinking water systems is required so that water quality issues are quickly identified and addressed. When a sample exceeds an Ontario Drinking Water Quality Standard or there is an observation of improperly treated drinking water, the laboratory and/or system owner must report the issue to the ministry and the local medical officer of health. Figure 2 outlines the process that must be followed when an adverse test result or observation occurs.

Figure 2 outlines the process that must be followed when an adverse test result or observation occurs

General notification process for adverse water quality incidents

Exceedance of a standard

The following reports are submitted to Spills Action Centre and local medical officer of health:

- laboratory verbally reports immediately

- operator verbally reports immediately

- laboratory submits written notification within 24 hours to the Spills Action Centre and local medical officer of health

- operator written notification within 24 hours to the Spills Action Centre and local medical officer of health

Observation of improper disinfection:

- operator required to verbally report immediately to the Spills Action Centre and local medical officer of health

- operator submits written notification within 24 hours to the Spills Action Centre and local medical officer of health

- operator submits final notification within 7 days of issue resolution

- ministry’s water inspectors follow-up as needed

It is important to note that the report of an adverse test or operational issue (for example, low chlorine or improper disinfection) does not necessarily mean that the drinking water is unsafe, but it does mean that the owner and operator need to investigate what may have caused the adverse result or operational issue and take all steps necessary to resolve it.

The ministry also follows up on lead exceedances and works with operators of schools and child care centres, as well as the local medical officer of health, to resolve issues. When a test result exceeds the standard for lead, facility operators must report the exceedance to the ministry, the local medical officer of health and the Ministry of Education. If a result from a flushed sample fails to meet the standard, owners and operators must take immediate action to make the tap or fountain inaccessible to children by disconnecting or bagging it until the problem is fixed. Other corrective actions can include increased flushing, replacing the fixture, or installing a filter or other device that is certified for lead reduction. Operators must also follow any other directions issued by their local medical officer of health.

The following section outlines the performance of our regulated drinking water systems and laboratories, drinking water test results, and enforcement activities and programs. The performance results show that Ontario’s drinking water systems continue to be well-operated, and our water is still among the best protected in the world. More detailed information on the following data is available on the Ontario Data Catalogue.

| Category | Number of drinking water systems and laboratories |

|---|---|

| Municipal residential drinking water systems | 652 |

| Non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems (for example, year-round trailer parks) | 460 |

| Systems serving designated facilities (for example, a school on its own well supply) | 1,388 |

| Licensed laboratories | 51 |

| Category | Number of tests results | Microbiological adverse test results | Chemical and radiological adverse test results | Percentage of test results meeting standards |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Municipal residential systems | 521,500 | 594 | 205 | 99.85% |

| Non-municipal year-round residential systems | 43,732 | 78 | 94 | 99.61% |

| Systems serving designated facilities | 63,831 | 113 | 64 | 99.72% |

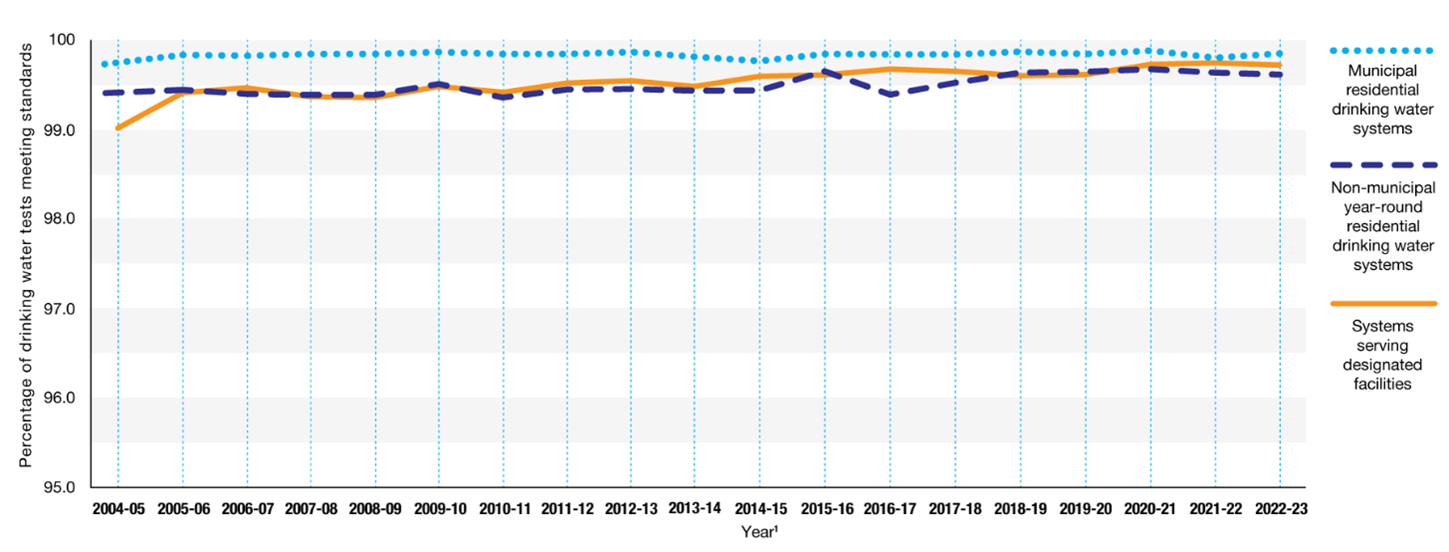

The consistent result of 99% for all 3 system categories demonstrates that the stringent regulations and requirements in place help to ensure that regulated drinking water continues to remain very safe in Ontario. The year-over-year

Figure 3: Trends in percentage of drinking water tests meeting Ontario Drinking Water Quality Standards, by system type

A chart showing trends in the percentage of drinking water tests that met standards for municipal residential drinking water systems, non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems and systems serving designated facilities over 16 years. The trend is consistent for all 3 system categories, showing that over 99% of drinking water test results since 2004-2005 have met standards.

For municipal residential drinking water systems, the percentage of drinking water test results that met the standards ranged from 99.74% in 2004-2005 to 99.85% in 2022-2023.

For non-municipal year-round drinking water systems, the percentage of drinking water test results that met the standards ranged from 99.41% in 2004-2005 to 99.61% in 2022-2023.

For systems serving designated facilities, the percentage of drinking water test results that met the standards ranged from 99.06% in 2004-2005 to 99.72% in 2022-2023.

| Category | Number of adverse water quality incidents | Number of systems reportings |

|---|---|---|

| Municipal residential systems | 1,256 | 324 |

| Non-municipal year-round residential systems | 454 | 200 |

| Systems serving designated facilities | 469 | 326 |

| Sample type | Total number of results | Number of test results meeting Ontario’s Drinking Water Quality Standard | Number of lead exceedances (of total number of results) | Percentage of test results meeting Ontario’s Drinking Water Quality Standard |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lead – Flushed | 13,591 | 13,376 | 215 | 98.42% |

| Lead – Standing | 13,580 | 13,018 | 562 | 95.86% |

| Lead – Total for standing and flushed samples | 27,171 | 26,394 | 777 | 97.14% |

| Category | Number of test results | Percentage meeting the drinking water standard for lead |

|---|---|---|

| Municipal residential drinking water systems | 5,734 | 93.34% |

| Non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems | 1,036 | 99.13% |

| Category | Number of inspections |

|---|---|

| Municipal residential drinking water systems | 652 |

| Non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems | 104 |

| Systems serving designated facilities | 301 |

| Schools and child care centres (lead) | 172 |

| Licensed laboratories | 101 |

| Category | Number of sent year-at-a-glance reports |

|---|---|

| Non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems | 283 |

| Systems serving designated facilities | 866 |

| Category | Number of facilities | Percentage of drinking water fixture inventories submitted | Percentage declaring sampling is completed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Schools and child care centres | 11,131 | 94% | 85% |

Inspection ratings

The ministry assigns a rating to each inspection conducted at a municipal residential drinking water system or licensed laboratory. A risk-based inspection rating is calculated based on the number of non-compliance items identified during an inspection of a system or laboratory, and the significance of those administrative, environmental and/or health consequences.

In 2022-2023:

- 76% of municipal residential drinking water systems received a 100% rating

- 99.8% of municipal residential drinking water systems received an inspection rating above 80%

- 75% of laboratories received a 100% rating in at least 1 of their inspections

- 37% of laboratories received a 100% in both inspections

- 100% of laboratory inspections received ratings above 80%

An inspection rating of less than 100% does not indicate that drinking water is unsafe. It identifies areas where changes may need to be made to improve the operation of a drinking water system or laboratory. In these situations, the ministry uses a range of compliance tools to help ensure that the owners address specific areas requiring attention.

Common instances of non-compliance for drinking water systems included failing to ensure:

- that continuous monitoring equipment is performing and recording tests correctly

- treatment equipment is properly operated (for example, using the correct dosage of chlorine, confirming that filters are performing properly)

- logbooks are properly maintained and contain the required information

- persons operating the drinking water system possess the proper designation and training

- reporting requirements for adverse water quality incidents are met

- microbiological samples are collected at the proper frequency and correct location

Common instances of non-compliance for licensed laboratories included failing to ensure:

- documentation and record-keeping contain sufficient detail

- policies and procedures are up to date

- that laboratory personnel are conducting drinking water testing according to the licensed test method

- that adverse results are reported, and that the reports include all the required information

Deficiencies, infractions and orders

Deficiencies and infractions

The Compliance and Enforcement regulation made under the Safe Drinking Water Act, 2002 (Ontario Regulation 242/05) requires that the ministry undertake mandatory action for deficiencies identified at municipal residential drinking water systems and infractions at laboratories. Mandatory action may consist of various measures, such as issuing an order or referring non-compliant behaviour for investigation.

A ‘deficiency’ in this context means a violation of prescribed provisions of the Safe Drinking Water Act, 2002 and its regulations that poses a drinking water health hazard. For example, water treatment equipment that is not operated according to provincial requirements may impact the quality of drinking water and adversely affect the health of those using the system. In the context of the Compliance and Enforcement regulation, an ‘infraction’ means a violation of prescribed provisions of the Safe Drinking Water Act, 2002 and its regulations in respect of a licensed laboratory. For example, a laboratory’s failure to report an adverse test result to the owner of a drinking water system could result in the system owner not taking corrective action.

In 2022-2023, the ministry did not identify any deficiencies during inspections of municipal residential drinking water systems.

There were 5 infractions identified at 5 licensed laboratories. Four were tied to late adverse reporting and 1 to testing parameters without a licence. The owners of these laboratories were issued orders requiring them to take corrective action.

The following orders were issued in 2022-2023 (including those issued as a result of an infraction):

Non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems

Four orders were issued to owners of non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems. The orders required:

- For a system that did not have a certified operator or an operating authority to operate the system, as required by law, an order was issued requiring the owner to retain a certified operator or an operating authority to operate the drinking water system; provide proof of a written contract between the owner and the certified operator; and increase the frequency of distribution system microbiological sampling from bi-weekly to weekly.

- For a system whose UV disinfection system had failed, the owner was ordered to service and repair the UV disinfection system and solenoid valve to ensure all treatment equipment was in proper working order, remove bypass plumbing around the solenoid valve, and develop a standard operating procedure to ensure that the reporting requirements in Schedule 16 of Ontario Regulation 170/03 are met.

- For a system that the owner was failing to properly maintain, and which had multiple instances of non-compliance, an order was issued requiring the drinking water system’s well to be properly fitted with a vermin-proof well cap; photos of the completed work to be submitted to the provincial officer; and submission of maintenance, operational and sampling records to the provincial officer for the following 4 months.

- For a system that did not have a Certified Operator, as required by law, and had therefore been made the subject of a boil water advisory, an order was issued requiring the owner to provide weekly summary reports of system operations including sampling reports, operational, maintenance and alarm records; retain a certified operator to operate the drinking water system along with proof of a written contract between the owner and the certified operator; and develop a contingency plan that includes procedures to ensure the site is operated by a certified operator.

- Three of these owners complied with their orders within the timeframe directed in the orders, 1 orderee failed to meet the deadlines but eventually brought their system into compliance, and the owner of 1 of the systems continues to submit required quarterly reports at this time.

Systems serving designated facilities

Two orders were issued to owners of systems serving designated facilities.

- For a system whose well had not been properly maintained and which was not adequately treating its water, an order was issued requiring the:

- preparation of engineering evaluation report by a licensed engineering practitioner and then requiring the operation of the drinking water system in accordance with the report once prepared

- calibration of the owner’s hand-held direct readout chlorine analyzer by a third party to confirm that it is reading accurately or to obtain a new hand-held unit to ensure accurate readings

- owner to ensure that all persons collecting water samples from the drinking water system have reviewed the owner's manual for the chlorine testing equipment being used and are obtaining test results in accordance with the user manual

- submission of records of daily treated chlorine residuals for the following two months

- provision of bottled water to the tenants of the site until it was determined that all treatment equipment met the requirements of Ontario Regulation 170/03 and was being maintained.

- A provincial officer’s order was issued to the owner of a system servicing a retirement home, and the owner requested that the Director review the order. This was done, and the Director issued a Director’s Order which largely upheld the provincial officer’s order with some modifications, and which required the owner to:

- undertake visual inspections of the cistern, log the findings and report any findings that may indicate the cistern is failing or contamination has occurred until a new cistern was installed

- collect 1 distribution water sample every two weeks and test it for microbiological parameters

- retain the services of a qualified person to install a new cistern

- provide a timeline and date of completion for the installation of the new cistern

- provide written confirmation that the installation of the new cistern is complete, and that the old cistern has been disconnected from the drinking water system

- One of these owners complied with their order within the timeframe directed in the orders and 1 orderee failed to meet the deadlines but eventually brought their system into compliance.

Licensed laboratories

Five orders were issued to the owners of 4 separate licensed laboratories. The orders required:

- In the case of a laboratory that had failed to report adverse water quality test results immediately, as required by law, the order required the owner to review the laboratory’s quality management system regarding the identification, processing and immediate reporting of adverse results, and identify deficiencies and implement corrective actions, including staff training on the identification, processing and immediate reporting of adverse results which contributed to this non-compliance.

- In the case of a laboratory that had not reported an adverse water quality incident as required by law, the order required the owner to conduct a root cause analysis to identify deficiencies in the laboratory system for flagging adverse drinking water test results and all procedures for adverse drinking water test reporting. The root cause analysis was required to include a review of their current quality management system regarding the identification, processing, and immediate reporting of the prescribed adverse water test results. The order further required the owner to train staff on the processing and immediate reporting of adverse drinking water quality test results, and to implement any other corrective actions to address deficiencies identified in the root cause analysis.

- In the case of a laboratory that failed to immediately report an adverse water quality incident as required by law, an order was issued requiring a review of the laboratory’s quality management system regarding the identification, processing and immediate reporting of adverse results, and to identify deficiencies and implement corrective actions, including staff training, on the identification, processing, and immediate reporting of adverse results which contributed to the non-compliance identified in the order.

- In the case of a laboratory that was providing drinking water testing services not authorized by its drinking water testing license, an order was issued requiring the immediate cessation of any drinking water testing for fluoride until licensing or authorization to test for fluoride is obtained, and requiring a review of the laboratory’s quality management systems regarding accreditation and licensing policy as well as requiring the owner to identify current gaps and implement corrective actions, including staff training, to improve the laboratory’s accreditation and licensing policy and procedure.

- In the case of a laboratory that had not reported an adverse drinking water test result in the manner required by regulation, an order was issued requiring a review of the laboratory’s current quality management system regarding the identification, processing and 24-hour written reporting of lead exceedances under Ontario Regulation 243/07 under the Safe Drinking Water Act, 2002, and also requiring the owner to identify deficiencies and implement corrective actions, including staff training, on the identification, processing and immediate reporting of adverse results which contributed to this non-compliance.

- All owners have complied with the orders.

Convictions

In 2022-2023, owners and/or operators of 3 systems that supplied drinking water to municipal and non-municipal residential systems were charged with offences under the Safe Drinking Water Act, 2002 and convicted and fined for a combined total of $128,000.

These convictions were as follows:

Municipal residential drinking water systems

- The owner and operator of a municipal drinking water system were jointly charged with offences relating to non-compliance with the conditions of a Provincial Officer’s Order and non-compliance with provisions of the Safe Drinking Water Act, 2002 and its regulations. The owner was convicted of failing to keep records of drinking water tests required under Schedules 6 and 7 of Ontario Regulation 170/03 for at least two years, specifically continuous monitoring data for free chlorine residual, and fined $6,000 plus Victim Fine Surcharge. The corporate operator was convicted of: failing to operate continuous equipment at the system, namely the chlorine analyzer, in accordance with prescribed standards, by failing to ensure a qualified person took appropriate action when there was good reason to believe that continuous monitoring equipment was malfunctioning; failing to comply with conditions of a Provincial’s Officer’s Order by failing to measure the rate of flow through the chlorine residual analyzer at the drinking water system on a daily basis and record this information; and failing to keep records of drinking water tests required under Schedules 6 and 7 of Ontario Regulation 170/03 for at least two years, specifically continuous monitoring data for free chlorine residual. Additionally, the sole director of the corporate operator was convicted of the same offence of non-compliance with the Provincial Officer’s Order. The corporate operator was fined a total of $13,500 and the director of the corporation was fined $1,500, plus Victim Fine Surcharge.

- A municipality was charged as both the owner and operating authority of a system. As the owner, they were convicted of failing to exercise a level of care, diligence or skill in respect of the municipal drinking water system that a reasonably prudent person would be expected to exercise in a similar situation. As the operating authority, they were convicted of operating a municipal drinking water system without a valid operator’s certificate. The municipality was fined $100,000 plus Victim Fine Surcharge.

- This was the ministry’s first conviction under Section 19 of the Safe Drinking Water Act, 2002. This section sets out the legal responsibilities and duties of persons who oversee municipal drinking water systems and expressly extends legal responsibility to people with decision-making authority over municipal drinking water systems and those who oversee the accredited operating authority for the system. These responsibilities and duties are commonly described as either a duty of care or standard of care.

Non-municipal year-round residential systems

- The owner and operator of a communal drinking water system that serviced a mobile home park was charged with a number of offences under the Safe Drinking Water Act, 2002 relating to non-compliance with a Director’s Order. The owner/operator was convicted of two charges of failing to comply with items in a Director’s Order that had been issued to the owner/operator, those two non-compliances being:

- failing to retain the services of a certified operator or operating authority to operate the drinking water system

- failing to provide users of the drinking water system monthly written notices door-to-door to remind them of any applicable drinking water advisory in effect for the system

- The owner/operator was fined a total of $7,000 plus Victim Fine Surcharge

Compliance and enforcement regulation

The Compliance and Enforcement Regulation (Ontario Regulation 242/05) made under the Safe Drinking Water Act, 2002 outlines the requirements the ministry’s compliance program must meet. Requirements met this year included:

- completing an inspection at all 652 municipal residential drinking water systems in the province

- completing 2 inspections at each of the 51 licensed laboratories in the province

- 1 laboratory left the program mid-year and so did not require a second inspection

- conducting at least 1 of the 2 inspections at each licensed laboratory unannounced

- issuing all inspection reports for municipal residential drinking water systems and licensed laboratories within 45 days of the completion of the inspection

- taking mandatory action within 14 days of finding a deficiency at a municipal residential drinking water system or an infraction at a licensed laboratory

The ministry did not meet the requirement to conduct every third inspection of municipal drinking water systems unannounced — 1 inspection was conducted announced when it should have been unannounced. The ministry is taking corrective action to ensure all requirements under the Compliance and Enforcement Regulation are met, including stricter adherence to standard operating procedures concerning scheduling of unannounced inspections. Training was provided to staff on the importance of the Compliance and Enforcement Regulation and its requirements.

In addition to setting requirements for inspection and compliance activities, the Compliance and Enforcement regulation also provides the public with the right to request an investigation of an alleged contravention of the Safe Drinking Water Act, 2002 or any of its regulations. In 2022-2023, there was 1 request for investigation.

The ministry received an Application for Public Drinking Water Investigation and supporting information in February 2023 requesting an investigation into alleged violations of the Safe Drinking Water Act, 2002 at a residential apartment building. The ministry’s Environmental Investigations and Enforcement Branch reviewed the request and determined that the allegations did not fall within the scope of the legal requirements set out under the Safe Drinking Water Act, 2002 and its regulations. As a result, the ministry did not conduct an investigation of the events and the applicant was informed that the ministry would not be initiating an investigation into the allegations within 60 days of receiving the application, as required by the regulation.

Information on drinking water quality, inspections, orders and convictions data is available on the Ontario Data Catalogue.

2022-2023 highlights of Ontario’s small drinking water system results

Across Ontario, thousands of businesses and other community sites use a small drinking water system to supply drinking water to the public. These places may not have access to a municipal drinking water supply and are most often located in semi-rural and remote communities.

These small drinking water systems, which are regulated under the Health Protection and Promotion Act and 1 of its regulations, Ontario Regulation 319/08 (Small Drinking Water Systems), provide drinking water in restaurants, medical offices, places of worship and community centres, resorts, rental cabins, motels, lodges, bed and breakfasts, campgrounds, and other public settings.

The Small Drinking Water Systems Program is a unique and innovative program overseen by the Ministry of Health and administered by local boards of health. Public health inspectors conduct inspections and risk assessments of all small drinking water systems in Ontario, and provide owner/operators with a tailored, site-specific plan (i.e., a Directive) to help keep drinking water safe. This customized approach has reduced unnecessary burden on small drinking water system owner/operators without compromising provincial drinking water standards.

Owners and operators of small drinking water systems are responsible for protecting the drinking water that they provide to the public. They are also responsible for meeting Ontario’s regulatory requirements, including regular drinking water sampling and testing, and maintaining up-to-date records.

2022-23 at a glance:

- Over the past decade, we have seen increasingly positive results including a steady decline in the proportion of high-risk systems (8.58% in 2022-23 down from 16.65% in 2012-13). The total number of systems is relatively stable from year to year. It fluctuates up and down only slightly.

- Risk category is determined based on water source, treatment, and distribution criteria. High-risk small drinking water systems may have a significant level of risk and are routinely inspected every 2 years. Low and moderate risk small drinking water systems may have negligible to moderate risk levels and are routinely inspected every 4 years.

- Public health inspectors often work with the operator to address potential risks, which, when corrected, may result in a lower assigned category of risk.

- As of March 31, 2023, over 3 quarters (79.57%) of small drinking water systems are categorized as low risk and a total of 91.42% of systems are categorized as low and moderate risk, and subject to regular re-assessment every 4 years.

- The remaining systems, categorized as high risk, are re-assessed every two years.

- 98.24% of 91,445 drinking water test results (46,277 samples) submitted from small drinking water systems during the reporting year have consistently met Ontario drinking water quality standards as set out in Ontario Regulation 169/03. Public health inspectors work with the system owners and operators to bring their systems into compliance.

- As of March 31, 2023, 26,669

footnote 4 risk assessments have been completed for the approximately 10,000 small drinking water systems since the inception of the current program in December 2008. The risk assessment is used by public health inspectors to develop the directive for the system, which is a site-specific plan for the operator. The directive may include requirements regarding:- The frequency and location of sampling

- Water samples to be taken and tested for biological, chemical, radiological, or other potential contamination

- Operational tests such as checking disinfection levels and conducting turbidity tests

- Operator training

- Record-keeping

- Installation of treatment equipment

- Posting and maintaining warning signs

- Through the Ministry of Health’s Small Drinking Water System Program, public health units provide information to small drinking water system owners and operators on:

- how to protect their drinking water at the source by identifying possible contaminants

- how and when to test their water

- treatment options and maintenance of treatment equipment, where necessary

- when and how to notify the public, whether in relation to a poor water sample test result or equipment that is not working properly

- what actions need to be taken to mitigate the problem

In the event of an adverse test result, the laboratory involved will notify both the owner/operator of the small drinking water system and the local public health unit for immediate response to the incident. Details of the adverse water quality incident will also be tracked by the public health unit in the Drinking Water Advisory Reporting System.

Adverse water quality incidents can result from an observation (for example, an observation of treatment malfunction) or adverse test result (i.e., water sample does not meet drinking water standards under Ontario Regulation 169/03).

- Since 2013-2014, a significant downward trend in both total adverse water quality incidents and the number of systems that reported an adverse water quality incident has occurred, with some fluctuations:

-

- In the past year, the total number of adverse water quality incidents remained the same as the previous year (907) and the number of small drinking water systems that reported an adverse water quality incident (decreased slightly from 694 in 2021-22 to 672 in 2022-23).

footnote 5 - Overall, the total number of incidents in 2022-23 is still down 40.21%; and 44.74% fewer systems reported an adverse water quality incident compared to 2013-2014 data, at 1,517 adverse water quality incidents for 1,216 systems.

- In the past year, the total number of adverse water quality incidents remained the same as the previous year (907) and the number of small drinking water systems that reported an adverse water quality incident (decreased slightly from 694 in 2021-22 to 672 in 2022-23).

-

The small drinking water system adverse water quality incident data demonstrates the success of the Small Drinking Water System Program. Adverse incidents are now being systematically captured and appropriate action can now be taken and tracked to help protect drinking water users.

Reductions in adverse water quality incidents in small drinking water systems have occurred over time since the start of the program, as owners/operators have complied with sampling requirements in accordance with their directives and have instituted improvements in their drinking water systems.

Note, the Ministry of Health is not aware of any reported illnesses related to these incidents. This may in part be because, through the Small Drinking Water System Program, operators now know when and how to notify users that their drinking water may not be safe to drink and are working with public health units to take appropriate corrective actions to mitigate any potential problems.

Conclusion

Our ministry and partner ministries, municipalities, private system owners and operators, the Walkerton Clean Water Centre, local Public Health Units, licensed laboratories and many others remain dedicated to protecting public health through the delivery of safe and sustainable drinking water in Ontario.

We maintain our commitment to move forward with initiatives and actions to protect water so that when you turn on your tap, you can be confident that your drinking water is among the best protected in the world.

Footnotes

- footnote[1] Back to paragraph There were slight variations in the methods used to tabulate the percentages year-over-year due to regulatory changes and different counting methods.

- footnote[2] Back to paragraph A tailored report, which summarized available ministry data, including drinking water system profile information, sampling information and a list of adverse water quality incidents reported for their system.

- footnote[3] Back to paragraph The ministry is following up with owners of schools and child care centres of the remaining inventories to determine whether they met the requirement to sample all fixtures.

- footnote[4] Back to paragraph The reported number of risk assessments will change as new systems come into use/change in use, and routine re-inspections and risk assessments are completed. Risk categories may also fluctuate (for example, if recommended improvements are taken to reduce the system’s risk). Similarly, a system may require reassessment to determine if the risk level has changed (for example, if the water source or system integrity is affected by adverse weather events or system modifications).

- footnote[5] Back to paragraph An adverse test result does not necessarily mean that users are at risk of becoming ill. When an adverse water quality incident is detected, the small drinking water system owner/operator is required to notify the local medical officer of health and to follow up with any action that may be required. The public health unit will perform a risk analysis and determine if the water poses a risk to health if consumed or used and may take additional action as required to inform and protect the public. Response to an adverse water quality incident may include issuing a drinking water advisory that will notify potential users if the water is safe to use and drink or if it requires boiling to render it safe for use. The public health unit may also provide the owners and/or operators of a drinking water system with necessary corrective action(s) to be taken on the affected drinking water system to address the risk.