Fall cutting of alfalfa

Learn about stresses on alfalfa stands, critical fall harvest dates and late fall cutting of alfalfa.

When weather conditions reduce forage inventories, it can be very tempting to cut some alfalfa for haylage or baleage in the fall. This difficult decision will need to weigh the immediate need for forage against the increased risk of alfalfa winterkill and reduced yields next spring. How do we evaluate these risks?

What Stresses Alfalfa Stands?

Poor fertility is possibly the most common stressor on alfalfa. Hay crops remove 6.1 kg P2O5 and 23.5 kg K2O per tonne of dry matter yield. Fall application of these nutrients help improve winter hardiness. Taking a soil sample for analysis will help producers develop a fertility plan. Recommended rates based on soil test results can be found in OMAFRA Publication 811: Agronomy Guide for Field Crops.

Freeze-thaw events over the winter months can create stressful conditions. Snow cover insulates alfalfa crowns against low temperatures, and the loss of this blanket increases the likelihood of winter injury. Water ponding and ice sheeting prevent oxygen from reaching the roots, and draw heat away from the crown.

Insects and diseases also pressure alfalfa plants. Alfalfa weevil is most common in southwestern Ontario, and typically reaches 3rd and 4th instar (the most damaging life stages) around the time of first cut. Potato leafhopper is often the most economically significant pest, but the severity of infestation is difficult to predict, as the leafhoppers do not overwinter, but are blown in from the United States on storm fronts.

A major contributing factor to poor first-cut yields is always cutting alfalfa during the fall. With forage inventory shortfalls, it is understandable why many take that risk. However, we have been seeing more winterkill recently, even in areas where it is less common. Stressed, weakened stands are at a greater risk of continued decline and poor yield. Digging some alfalfa crowns and roots and doing an assessment for disease and plant health can help in making fall cutting and rotation decisions. Refer to Alfalfa Stand Assessment.

Critical Fall Harvest Period

The Critical Fall Harvest Period for alfalfa is the 6-week rest period (450 Growing Degree Days, base 5°C) preceding the average date of the first killing frost, when alfalfa stops growing. Not cutting during this period allows alfalfa plants to re-grow and build up sufficient root reserves to survive the winter and grow more aggressively in the spring. When cut early in the period the alfalfa will use the existing root reserves for regrowth, "emptying the tank". Later in the period, the alfalfa uses photosynthesis to produce carbohydrates and stores them as root reserves, "refilling the tank". Cutting in the middle, of the Critical Period (3rd or 4th week), when root reserves have been depleted and not yet replenished, is usually higher risk than cutting at either the beginning or end of the Period.

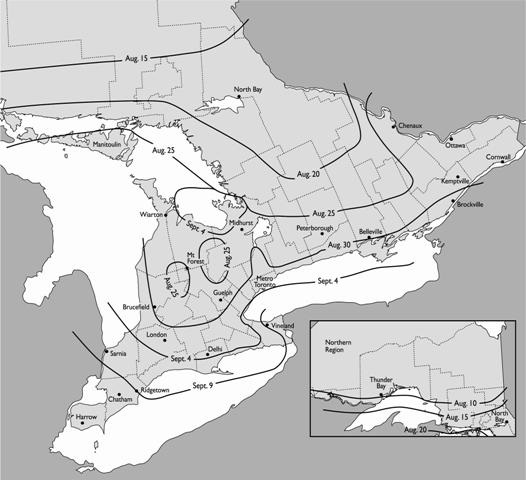

The Critical Fall Harvest Period begins around August 10th in northern Ontario, August 25 - 30th for eastern and central Ontario, and September 4th in the southwest (Figure 1). However, it is difficult to predict when that killing frost will actually occur. The actual date seldom occurs on the average date, so the beginning of the Critical Fall Harvest Period is a guideline only.

Figure 1. Start of the six-week alfalfa critical fall harvest period.

Even when winterkill does not occur, the extra yield harvested during the Critical Period is typically offset by reduced vigour and lower 1st-cut yields the following spring. It can sometimes be difficult to observe, but still be significant. Research shows that the yield sacrificed by not harvesting during the Critical Period is usually regained in first-cut yield the following year. The decision to cut in the fall should always be weighed against the immediate need for forage. If you do decide to cut, consider leaving some check strips that you can use for comparison next year.

Other Contributing Risk Factors

Fields with older stands, a history of winterkill, low potassium soil tests, low pH, poor drainage, or insect and disease pressure are at increased risk of winterkill and are poor candidates for fall harvesting. Fall harvest of new seedings is generally not recommended. Aggressive cutting schedules with cutting intervals of less than 30 days between cuts increases the risk of winterkill, while intervals over 40 days (allowing flowering), reduces the risk. We frequently see fields with disappointing first-cut yields where fourth-cut was taken the preceding fall.

Some areas of the province, such as the Ottawa Valley, have a higher historical risk of winterkill. In situations where forage inventories are adequate, increasing the risk of winterkill by fall cutting is far less acceptable.

Late Fall Cuttings at the End of the Critical Fall Harvest Period

If fall harvest must be done, risk of winterkill can be reduced (but not eliminated) by cutting towards the end of alfalfa growth, close to a killing frost. Little root reserves will be depleted by regrowth, but lack of stubble to hold snow to insulate the alfalfa crowns against damage during cold weather may be a problem. Increasing cutting height to 15 cm (6 inches) of stubble will help. Try to limit late cuttings to fields that are otherwise lower risk - well drained, good fertility, healthy crowns and roots, etc. A killing frost occurs when temperatures reach about -4°C for several hours. After a killing frost, alfalfa feed value will quickly decline, as leaf loss occurs and rain leaches nutrients quickly.

Insufficient top growth and snow holding capacity can also contribute to alfalfa frost heaving. If winter ice sheeting occurs, stubble will protrude through, allowing air to get under the ice. Cut alfalfa initiates regrowth from crown buds and axillary buds, not the cut end of the stem, so cutting higher does not reduce usage of root reserves. However, cutting higher does allow for holding more snow as insulation.

Smothering

There is always the question of smothering in heavy forage stands that are left unharvested. Heavy stands of grasses or red clover can sometimes smother over the winter because the top growth forms a dense mat. In contrast, alfalfa loses most of its leaves as soon as there is a hard frost, and the remaining stems remain upright and seldom pose any risk of smothering.

More Information

For more information, refer to Risk of alfalfa winterkill.