Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change: Minister’s Annual Report on Drinking Water 2016

The report is an overview of the government’s programs, policies and initiatives to protect drinking water, containing information on:

- Ontario’s drinking water systems’ performance

- working to protect the Great Lakes

- improving drinking water for First Nations

- the second progress report on implementing the Water Opportunities Act

Minister’s message

As Minister of the Environment and Climate Change, it’s my great pleasure to share our 10th annual report on Ontario’s drinking water.

From source to tap, clean and safe drinking water for all Ontarians is a top priority for our government. The work we are doing with Indigenous communities, federal and municipal governments and local communities across Ontario is helping protect our rivers, streams and lakes to safeguard our drinking water and its sources.

Our collective efforts over the past year have helped ensure Ontario’s drinking water continues to be among the best protected in the world.

As part of the year’s achievements, I am pleased to note that 99.8 per cent of more than 527,000 test results from municipal residential drinking water systems met Ontario’s strict drinking water quality standards in 2015-2016. We are also working collaboratively with Indigenous communities and the federal government to improve drinking water for First Nation communities by providing technical support and helping to train drinking water system operators.

Over the past year, we also took important steps to protect sources of our drinking water. Beginning December 16, 2016, Ontario has put in place a two-year moratorium on new or expanded water takings from groundwater by water bottlers in the province as well as stricter rules for renewals of existing permits.

We are helping protect Lake Erie by adopting a target of 40 per cent phosphorus load reduction to help reduce algal blooms. We have also set up the Great Lakes Guardians’ Council with co-chair Grand Council Chief Patrick Madahbee of Anishinabek Nation to help guide our work on Great Lakes.

Keeping our drinking water protected and improving the ways we do this is a shared responsibility, especially as we face the effects of climate change. Ontario passed landmark legislation in 2016 that lays a foundation to reduce our greenhouse gas emissions and plan, prepare and adapt to a changing climate.

These are critical steps, but there is more work to be done.

Combatting blue-green algal blooms, developing new standards for drinking water, and working on emerging issues such as microplastics and microbeads are a few of the ongoing projects we will tackle in the year ahead.

Our ministry is committed to working collaboratively across ministries, Indigenous communities, municipalities, conservation authorities, communities, water agencies — and with you — to make sure we all have access to clean, safe drinking water. Working together, we will fight climate change and protect Ontario’s drinking water for present and future generations.

The Honourable Glen Murray

Minister of the Environment and Climate Change

Government of Ontario

Overview of sections

This report covers the wide range of actions being taken with many partners to protect drinking water and its sources while addressing the impacts of climate change.

Climate change — The newest provincial legislation and Ontario’s Climate Change Action Plan, how Ontario monitors water and the relationship to climate change.

First Nations — How Ontario is collaborating in an atmosphere of reconciliation and respect, working with First Nation communities and the federal government to help improve drinking water on reserves, with a focus on remote communities.

The Great Lakes — Provincial, national and international efforts to restore, protect and conserve these lakes, including the release of the first progress report on Ontario’s Great Lakes Strategy.

Water Opportunities Act — Includes the second progress report on implementing the act and Ontario’s actions to encourage efficient water use and innovative water management and to strengthen municipal infrastructure planning.

Source protection — How Ontario is leading the call to protect drinking water sources through community developed policy and innovative tools.

Ontario’s drinking water — An overview of Ontario’s drinking water quality and the ministry’s activities that help ensure safe drinking water for the people of Ontario.

Emerging issues — The next stages in Ontario’s water protection and the science used to address these issues, including new information on microplastics.

Climate change

Climate change is a global problem with local effects. In Ontario, many of the effects relate to water. Intense rain, flooding, low water levels, drought and more extreme weather conditions are damaging homes, communities, businesses, crops and infrastructure.

Climate change may pose a threat to both the quantity and quality of water. As average summer temperatures are on the rise in Ontario, the demand for water for agricultural irrigation and household use is also increasing. At the same time, we are experiencing an increased variability in precipitation, greater levels of evaporation, shorter winters and altered snowfall patterns. This is changing groundwater quantities and surface runoff patterns, resulting in warmer lakes and streams and changes to seasonal processes and water quality.

As reported in the Minister’s Five Year Report on Lake Simcoe that was released in 2015, many communities in the Lake Simcoe watershed are being impacted by climate change. For example, climate warming has already shortened the duration of ice cover on Lake Simcoe by one full day on average per year since 1989, which in turn has shortened the ice-fishing season, a primary recreational activity that is important to the local economy.

Climate change is also exacerbating other stresses such as habitat loss and pollution, and can contribute to excess algae growth and invasive species infestations. Warmer water could mean changes in the types and populations of species, worsening microbial and algal problems and change the distribution of warm-water and cold-water fish populations throughout the province. The Great Lakes are among the most rapidly warming on a global scale. Temperature increases close to or above the average rise (0.34 degrees Celsius) were seen in Lake Huron, Lake Ontario and Lake Superior.

The effects of these changes and their impact on drinking water are of concern given the vulnerability of our water management and treatment infrastructure. Changes in water levels, heavy and sudden rainfalls and changes in water quality due to warmer water temperatures will further stress our aging physical structures and operational systems may not be able to cope.

The average age of Ontario’s infrastructure — roads, bridges, buildings, and sewer systems — is 15.4 years.

In 2015, the ministry released its Climate Change Strategy which sets out the government’s vision for Ontario to 2050 and outlines the path to a prosperous, low-carbon society. The strategy also commits to establishing a Climate Change Collaborative to deliver climate information services across the province to help decision-makers in both public and private sectors consider the risks of climate impacts in their operations.

Building on that progress, in 2016, Ontario passed the Climate Change Mitigation and Low-Carbon Economy Act and released a Climate Change Action Plan to implement the strategy over the next five years. The action plan identifies policies and programs to put Ontario on the right path to achieve its longer-term objectives.

The action plan includes working with a variety of partners such as businesses, homeowners, industries and municipalities.

Some action areas include:

- Providing incentives to homeowners and businesses to install or retrofit clean-energy systems like solar, battery storage, advanced insulation and heat pumps

- Providing better information about building energy use and updating the building code to increase energy efficiency over time

- Increasing the availability of zero-emission vehicles, deploying cleaner trucks and alternative fuels, improving transit and cycling infrastructure

The ministry is also taking action to address impacts of climate change on water by committing to improve its understanding of groundwater and by reviewing existing rules for adequate protection of groundwater for future generations. More details are provided in the section on protecting Ontario’s groundwater.

Visit the ministry’s website for more information on:

Role of monitoring programs

The ministry’s water monitoring programs look at climate change as one of the many factors affecting trends. The ministry relies on monitoring programs to help forecast future changes resulting from climate change such as impacts on lakes and streams.

At the ministry’s Dorset Environmental Science Centre, which is a centre of excellence for inland lakes research, ministry scientists use predictive models to forecast how lakes and streams will respond to future changes in climate (e.g. temperature and precipitation). The models are used to predict different climate impacts such as reductions in the water supply to lakes and streams, frequency of algal blooms, changes in winter ice cover, and changes in organisms affecting water quality. The Dorset climate models predict that average climate conditions for the Muskoka area will be both warmer and wetter with increased annual average temperature and precipitation. They also predict that there will be fewer days with ice cover on lakes. Knowing what these changes are and which types of lakes are most at risk will help inform future climate change adaptation and mitigation strategies.

In partnership with local Conservation Authorities the ministry’s Provincial Groundwater Monitoring Network program is an example of a program contributing to a better understanding of what might happen if particular climate trends continue. This network monitors baseline groundwater levels, groundwater chemical composition, local precipitation and how groundwater levels in some 480 wells are responding to changing land use activities and weather patterns associated with climate change. Monitoring wells show that groundwater levels close to the surface are getting lower. Owners of such wells may need to deepen them to maintain their water supply. Improving our scientific understanding of climate change impacts is part of the foundation for Ontario’s ability to adapt and to reduce the negative effects to drinking water and its sources.

First Nations

Improving First Nation communities’ access to safe drinking water continues to be a priority for Ontario. The ministry is working with First Nations to share its drinking water expertise and engineering experience in several areas. Steady progress is being made.

In Ontario, as of September 2016, there were 44 Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada-funded drinking water systems in 24 First Nations communities with long-term boil water advisories. Some of the longest-standing drinking water advisories in Canada are found in First Nation communities in Ontario.

Ontario is working with First Nation communities and the federal government to help deliver on the federal commitment to eliminate long-term drinking water advisories on reserves within five years.

Trilateral meetings with technical and political representatives from First Nations, Canada, and Ontario have been held to establish common principles and to develop a critical path forward to help resolve long-term drinking water advisories on Ontario reserves and to help ensure the long-term sustainability of drinking water systems. A working group is coordinated by the Ontario First Nations Technical Services Corporation and meets regularly.

Ontario is supporting the trilateral working group by offering in-kind technical assistance to First Nation communities and Tribal Councils across the province in several ways. This includes on-site assessment of current water systems, technical reviews of design and construction projects, reviewing operations and maintenance plans, operator training and certification, source protection and watershed planning. The ministry carried out a number of site visits in First Nation communities this year. During these site visits, the ministry worked closely with First Nations, Tribal Councils and federal technical staff and has gained valuable insight into the current state of drinking water systems on reserves, water system operator training and certification and source protection needs.

In June 2016, the Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change established the Indigenous Drinking Water Projects Office to offer assistance to First Nations by providing engineering and technical advice, services and support for drinking water and wastewater systems, and collaborating with First Nation communities and the federal government.

The ministry also supported a symposium on First Nations water, held in Niagara Falls in October 2016, by providing funding and planning input. This event provided an opportunity for First Nations leadership and technicians to exchange knowledge and expertise with industry, federal and provincial government representatives and others to address water and wastewater issues.

Ontario is continuing to work with First Nations and the federal government to develop an approach that will enable First Nation communities to leverage expertise, share and have access to the resources needed to help ensure clean water, while building local knowledge, developing local talent and respecting tradition and culture.

For further details on Ontario’s collaborative work with First Nations to improve access to drinking water on federal First Nation reserves, visit the ministry’s website.

The Great Lakes

The Great Lakes Protection Act became law in November 2015 and reflects extensive consultations and discussions with partners. This act sets the framework for working together to protect one of the world’s largest supplies of fresh water and a valuable drinking water source for many Ontarians.

Ontario’s Great Lakes Strategy — First progress report

Ontario’s Great Lakes Strategy outlines actions to achieve the province’s vision of healthy Great Lakes for a stronger Ontario — Great Lakes that are drinkable, swimmable and fishable.

The Great Lakes Protection Act requires Ontario to report on Great Lakes progress every three years and to review the strategy every six years. On March 22, 2016, Ontario released its first triennial progress report on Ontario’s Great Lakes Strategy.

The first progress report outlines some of the key accomplishments achieved to date under Ontario’s Great Lakes Strategy and highlights important new scientific research that points to the vulnerability of the Great Lakes and the need to continue to invest in science and monitoring. This will help us to better understand the threats so we can continue to take targeted action to restore and protect the Great Lakes ecosystem. It also includes updates related to protecting drinking water and discusses actions taken across 14 different ministries and others including Indigenous communities, municipalities, conservation authorities, environmental organizations, scientists, industries and the agricultural, recreational and tourism sectors.

For further information, see the full report.

Great Lakes Guardians’ Council

The Great Lakes Protection Act also established the Great Lakes Guardians’ Council, a forum involving Great Lakes ministers and other Great Lakes leaders and experts which will help improve collaboration and coordination and build consensus on priority actions and opportunities for partnerships and funding. The first council meeting was held on March 22, 2016, World Water Day, and the second council meeting was held on October 4, 2016, in conjunction with Great Lakes Week in Toronto.

At the October 2016 meeting, it was announced that Grand Council Chief Madahbee of the Anishinabek Nation and Minister Murray would be co-chairing the Guardians’ Council with additional leadership from the Anishinabek Chief Water Commissioner. The council meetings’ discussions included the development of a science and knowledge portal to bring together Great Lakes information and data and opportunities to build great connections to the lakes by gathering together diverse groups and communities to share, educate, celebrate and take action. The meeting summary notes can be found on the ministry’s website.

Lake Erie phosphorus reduction efforts

Lake Erie is the shallowest and most biologically productive of the Great Lakes, and receives high loads of phosphorus, making it highly sensitive to harmful blue-green and nuisance algal blooms. Excess nutrients, particularly phosphorus, are causing excess algal growth in Lake Erie that can pose a threat to human and ecosystem health, especially to drinking water quality.

Harmful blue-green algae blooms in the western basin and in various nearshore locations may contain toxins that can be harmful to humans and wildlife. To reduce algal blooms, Ontario is working with the federal government to develop a draft Canada-Ontario Action Plan for Lake Erie for public comment in spring 2017. This plan will contain actions to reduce phosphorus loads by 40 per cent to the western and central basins of Lake Erie. A target for the eastern basin will be established following further scientific assessment.

Protecting and restoring Lake Erie will take collaboration and coordination to achieve progress. So we are engaging the Great Lakes community, including First Nation and Métis communities, and key sectors on the development of a draft Action Plan for Lake Erie. Furthermore, a multi-sectoral Lake Erie Nutrients Working Group has been established to support this work.

Ontario’s Great Lakes Protection Act can help address algal blooms in Lake Erie. The act enables partners to come together to achieve shared goals in a particular watershed or geographic area in the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Basin.

Under the Great Lakes Protection Act at least one target must be set by November 2017 to assist in the reduction of algal blooms. Ontario has adopted a target of a 40 per cent phosphorus load reduction by 2025 (from 2008 levels) for the western and central basins of Lake Erie, as well as an aspirational interim goal of a 20 per cent reduction by 2020. A draft Canada-Ontario Action Plan for Lake Erie is currently being developed and these targets are consistent with what Ontario has adopted through the Canada-Ontario Agreement.

These efforts, along with the ministry’s 12 Point Action Plan to address and mitigate blue-green algal blooms, are enabling Ontario to take actions to prevent and respond to these harmful toxins in Lake Erie and beyond.

Although Ontario’s current nutrient reduction efforts are focused on Lake Erie, future efforts will be directed to Lake Ontario as the next priority Great Lake.

For more information on blue-green algae, see the Emerging issues section of this report.

Great Lakes Guardian Community Fund

Local action is key to protecting and improving the health of the Great Lakes. Through its Great Lakes Guardian Community Fund, Ontario has provided support for projects that engage people and their communities to help protect habitat and species. Efforts have included cleaning up beaches and shorelines, managing invasive species in wetland areas, increasing climate change resilience and planting trees and shrubs along stream banks.

In 2015-2016, Ontario committed to $1.5 million in funding for 86 projects led by not-for-profit organizations, schools, Indigenous communities and other local groups. Since 2012, the fund has provided $6 million to 305 projects.

Projects that have received funding include those with:

- Friends of the Rouge Watershed who engaged youth and other citizens to take action in Toronto’s Rouge Park. More than 3,500 students and 4,000 community members provided 6,500 hours of planting and watershed stewardship work. By planting native trees, shrubs, and flowers, these volunteers helped restore 29,000 square metres of land and habitat.

- The Catfish Creek Conservation Authority who worked to protect habitats and species in the Yarmouth Natural Heritage Area (near Aylmer, Ontario) by augmenting and creating new wetland habitat. Along with 30 volunteers and 25 students from local secondary schools, the group planted 11,300 native trees and Carolinian tall grass prairie. These activities helped reduce the quantity of nutrients entering the wetland and contributed to increasing biodiversity in the area.

- The Pays Plat First Nation (Pawgwasheeng) community who helped protect the sensitive coastal wetlands along the north shore of Lake Superior (about 175 kilometres northeast of Thunder Bay). The project involved building floating boardwalks with elevated viewing and ceremonial platforms and planting native trees and wetland plants.

Protecting groundwater in Ontario

In 2016, the ministry responded to growing public interest about the impact that water bottling operations are having on groundwater supplies and the ministry’s ability to effectively monitor and regulate these facilities.

Beginning December 16, 2016, Ontario has put in place a two-year moratorium on new or expanded water takings from groundwater by bottling companies, as well as stricter rules for renewals of existing permits. The moratorium will remain in effect until January 1, 2019.

During this time the ministry plans to:

- Undertake research to improve understanding of groundwater in Ontario

- Review existing rules for adequate protection of groundwater for future generations, considering the impacts of climate change and future demand on Ontario’s groundwater supplies, and

- Obtain input and feedback on groundwater management moving forward

Water Opportunities Act

This section highlights Ontario’s progress towards implementing the Water Opportunities Act. The first triennial report appeared in the Minister’s Annual Report on Drinking Water 2013 and progress has been made since then in the following areas:

- Encouraging Ontarians to use water more efficiently

- Strengthening municipal infrastructure planning

- Innovative water management

Water efficiency

Ontario recognizes that water conservation is everyone’s responsibility and is working with its partners to put this into practice. There are over 50 statutes, programs and policies that contribute to water conservation and efficiency.

The Green Energy Act, which was amended in 2016, presents new opportunities to conserve water and energy by enabling the implementation of two new conservation initiatives. First, the act prohibits the sale of products in Ontario that do not meet prescribed energy and water efficiency standards. In the summer of 2016, the Ministry of Energy proposed and consulted on new water efficiency standards for products such as clothes washers and dishwashers. Setting water efficiency standards for these products would reduce water and energy use and further lower greenhouse gas emissions.

The second energy and water conservation initiative is the proposed Large Building Energy and Water Reporting and Benchmarking program which will require commercial, multi-unit residential and some industrial buildings that are 50,000 square feet or larger to annually report their energy and water consumption and greenhouse gas emissions to the Ministry of Energy. The information will be benchmarked against other similar buildings, will be publicly disclosed and can help building owners better manage energy and water use and costs. It will also help the market value efficiency in purchasing, leasing and lending decisions.

Municipal infrastructure planning

On September 14, 2016, the federal and provincial governments announced a bilateral agreement to make funding available under the federal Clean Water and Wastewater Fund. The program is designed to accelerate short-term community investments, while supporting the rehabilitation and modernization of drinking water, wastewater and stormwater infrastructure.

The federal government is providing up to 50 per cent of this funding ($570 million) for projects while the provincial government will invest $270 million. Municipalities and local services boards will cover the remaining costs.

Innovative water management

Ontario also made progress on innovative water management through initiatives like the Water Technology Acceleration Project (WaterTAP), created under the Water Opportunities Act, and Ontario’s Showcasing Water Innovation program. Through the Showcasing Water Innovation program, Ontario has invested $17 million to support 32 projects across the province that enabled communities to pioneer cost-effective and innovative approaches to sustainable water management solutions. For further information, see the full report.

Ontario companies have incredible potential to increase their global market share. In 2016, WaterTAP placed a priority on clearing the path to enable water innovation and its adoption.

Through Ontario government agencies like the Walkerton Clean Water Centre and the Ontario Clean Water Agency, technology solutions are being connected with the locations where they can be tested, piloted and demonstrated. For example, in the six years since the Water Opportunities Act was introduced, the Ontario Clean Water Agency has worked with more than 70 technology companies and other partners to explore and facilitate technology pilots across the province.

These important achievements and innovative water management actions will all help encourage Ontarians to use water more efficiently, strengthen municipal infrastructure planning and help the province save water.

Source protection

Quality drinking water begins with protecting water at its source — surface and groundwater — and continues all the way through the many points to your tap. This is reflected in the ministry’s multi-barrier approach to delivering safe drinking water to Ontarians.

Involving local communities to drive both the development and implementation of local solutions that protect the quantity and quality of their water at its source has been a key factor in the ministry’s successful source protection approach.

This year the ministry focused on three key areas:

- Source protection plan implementation

- Improvements to provincial programs

- Public awareness of source protection

Progress towards implementation of source protection plans

Last year’s Minister’s report discussed the progress that was made by 19 local committees established under the Clean Water Act in developing 22 locally-led source protection plans that were all approved by the Minister. Source protection plans are the result of many years of hard work and local consultation with Indigenous communities, municipalities, farmers, industry and the public. They are based on strong science which is helping to address existing and potential risks to the quality and quantity of drinking water sources.

This year’s efforts focused on implementing these plans. More than 250 trained risk management officials and inspectors are assisting with this implementation phase. For example, risk management officials will be visiting properties around municipal wells and drinking water intakes to determine if the activity is one the activities identified as a risk to sources of drinking water. If it is, they will be working with the property owners to put in place a risk management plan that would best address the risk. Risk management inspectors will then periodically check in to make sure it was done and done correctly.

In 2016, the Lakehead Source Protection Authority was the first to submit an annual report for a source protection plan. It included a site-specific zoning amendment to protect certain agricultural lands, a salt management plan and outreach and education efforts to address local issues related to source protection.

This year the ministry also continued working with small, rural municipalities to implement source protection plans through the Source Protection Municipal Implementation Fund. To date, Ontario has committed $14.4 million to 199 small, rural municipalities to help offset implementation costs.

Improvements to provincial programs

Ontario has strengthened source protection by making changes to provincial and municipal spill response programs. The ministry’s spill response program now incorporates information on the location of wells, drinking water intakes and vulnerable areas around them so that drinking water system operators are notified about spills early and can take action to ensure drinking water remains safe.

The program has also helped improve agricultural practices around wells and intakes. Ontario’s Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs has, among other initiatives, integrated source protection into nutrient management certification training. It has also held education sessions with the Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change and Conservation Ontario for risk management officials who are involved in developing risk management plans for agricultural activities in source protection areas.

Public awareness of source protection

Over the past year a number of new tools were developed to increase public awareness of the importance of source protection. These tools are helping the public make informed decisions to protect their local sources of drinking water.

In February 2016, the ministry launched the Source Water Protection Map on Ontario.ca. The map is an innovative and interactive tool that provides the first province-wide view of the more than 970 wellhead protection areas and 150 intake protection zones within the source protection areas — the places where drinking water comes from. The public can access over 20 layers of information and do customized searches.

Another important tool for source protection is the installation of road signs on provincial and municipal roads to inform the public and early responders of the location of vulnerable drinking water supplies.

The ministry continues to build the catalogue of resources it launched in 2014 to help municipalities and conservation authorities implement source protection plan policies. The catalogue helps them carry out local education and outreach on the importance of water conservation and on risks to sources of municipal drinking water such as septic systems and road salt.

Two new pages on water conservation and the drinking water protection zone signs were posted on Conservation Ontario’s website in 2016.

The ministry continued to work with its partners to raise awareness of source protection through social media by using the hashtag, #SourceWaterON. The hashtag helps the ministry reach new social media audiences with an interest in protecting water sources and connects online conversations about source protection. The hashtag achieved an exciting milestone in 2016 — it was displayed more than one million times on social media.

Implementing plans and other actions to support source protection will help Ontario adapt to and mitigate the impacts that climate change may have on regulated drinking water.

Ontario’s drinking water

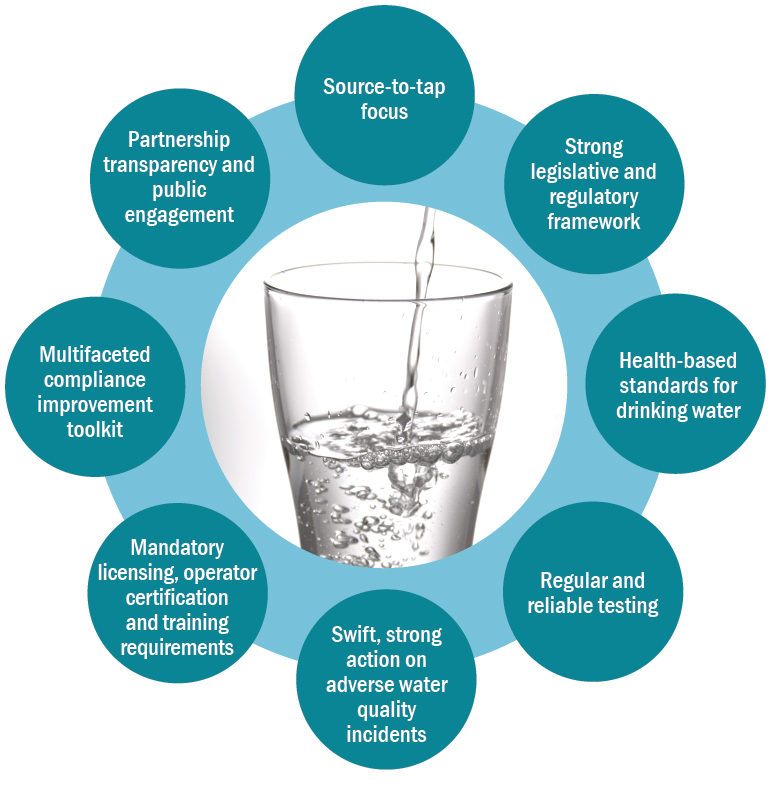

Whenever you turn on a tap, you can be confident that your drinking water is protected by a comprehensive safety net that starts at the source and continues right to your glass. Ontario’s eight-part system has extensive safeguards, like reliable testing and stringent standards, a legislative and regulatory framework and a commitment to transparency, that work together to help ensure Ontario’s regulated drinking water remains well-protected.

Figure 1: Ontario’s drinking water safety net

Ontario’s Chief Drinking Water Inspector reports on the performance of Ontario’s regulated drinking water systems every year. In addition to looking at performance, the report reviews the laboratories that test and analyze drinking water, the orders the ministry issues to enforce the regulations as well as any convictions against system owners/operators who fail to comply with the appropriate regulations.

For more information, see the Chief Drinking Water Inspector’s Annual Report 2015-2016 which covers the period from April 1, 2015 to March 31, 2016.

Drinking water quality standards

Ontario’s drinking water is protected by strict, health-based water quality standards that include limits for contaminants in drinking water. Most of these are based on Health Canada’s Canadian Drinking Water Quality Guidelines which undergo regular review and the ministry may choose to adopt a more stringent standard.

Last year, Ontario’s Drinking Water Quality Standards (Ontario Regulation 169/03) and Drinking Water Systems (Ontario Regulation 170/03) were amended. The amendments resulted in adopting new standards, strengthening existing standards and clarifying testing and sampling requirements for two substances. Two of the standards (benzene and vinyl chloride) are more stringent than Health Canada’s Canadian Drinking Water Quality Guidelines. These amendments will be phased in through 2020 and ensure that Ontario remains a leader in drinking water protection.

Progress in improving water quality and management of drinking water systems continues. In August 2016, the ministry began consulting on further amendments to regulations under the Safe Drinking Water Act through a posting on the Environmental Registry.

The Ontario Drinking Water Advisory Council also advises on drinking water quality and testing standards. See the Advisory Council’s website for more information on their work.

Key findings from the Chief Drinking Water Inspector’s Annual Report 2015-2016

More than 80 per cent of Ontario residents get their drinking water from municipal residential drinking water systems. Every year ministry staff inspect all municipal systems and the laboratories performing drinking water analysis for Ontario’s regulated drinking water systems to ensure they meet the province’s regulatory requirements.

In 2015-2016, these systems demonstrated consistently excellent results and continue to meet Ontario’s strict regulatory requirements.

All 663 municipal residential drinking water systems were inspected:

- 99.8 per cent of more than 527,000 test results from municipal residential drinking water systems met Ontario’s strict drinking water quality standards.

- The number of municipal residential drinking water systems that received a 100 per cent inspection rating increased seven percentage points, from 67 per cent in 2014-2015 to 74 per cent in 2015-2016.

- 99.5 per cent of municipal residential drinking water systems received an inspection rating greater than 80 per cent.

The ministry’s inspection results for all 52 laboratories that test Ontario’s drinking water (inspected at least twice per year) indicate that fifty-eight per cent of the inspections resulted in ratings of 100 per cent. Further, the ratings of all laboratory inspections increased five percentage points from 85 last year to 90 per cent this year.

Compliance and enforcement activities

Ministry inspectors have the authority to enforce Ontario’s drinking water protection laws. When drinking water system owners or operators and licensed laboratory owners do not comply with Ontario laws, inspectors may issue contravention and/or preventive measures orders. These orders aim to resolve and/or prevent non-compliance at a drinking water system.

In 2015-2016:

- 12 contravention and one preventative measures orders were issued to 13 non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems.

- One preventative measures order was issued to a local services board.

- Two systems serving designated facilities received two contravention orders.

- Two contravention orders were issued to two licensed laboratories.

There were two cases involving convictions at two systems serving designated facilities with fines totaling $6,000.

Operator certification and training

To ensure that Ontario’s certified drinking water operators are well qualified they must go through rigorous training. They follow the most stringent certification and training standards in Canada and are among the best trained in the world. To become and remain certified, operators must write examinations and meet mandatory experience and continuing education requirements. Depending on their certification level, drinking water operators must complete between 60 and 150 combined hours of continuing education and on-the-job practical training every three years to renew their certificates.

An operator must be trained according to the type and class of facility they operate. If an operator works in more than one type of drinking water system, he or she may hold multiple certificates. As of March 31, 2016, Ontario had 6,480 certified drinking water operators, holding 9,074 certificates. Of these, 157 were employed as system operators in First Nations across the province, holding 234 drinking water operator certificates.

The Walkerton Clean Water Centre

The Walkerton Clean Water Centre provides a platform for research on cost-effective solutions for small drinking water systems. In 2015-2016, the centre continued to provide leading-edge education, hands-on and classroom training, technology demonstrations and information and advice to drinking water system owners, operators and operating authorities across the province.

The centre provides province-wide training, including training on-site, with a focus on small and remote drinking water systems, including those serving First Nation communities. As of March 31, 2016, more than 62,500 new and existing professionals were provided with high quality operator training programs on water treatment equipment, technology and operating requirements, as well as environmental issues, including water conservation.

For more information, see the Walkerton Clean Water Centre’s website.

Open Data

As part of the Province’s commitment to an open, transparent and accountable government, Ontario launched its Open Data Initiative and the Open Data Catalogue.

As an early adopter and government leader on Open Data, the ministry began posting drinking water data to the Open Data Catalogue in December 2015 and has been updating the data on a quarterly basis.

Emerging issues

There are new challenges that have the potential to impact Ontario’s water. Being able to respond to them depends in part on a better understanding of the challenges and the ability to collaborate with partners. Ontario is taking action — continually searching for and using the best science to learn more about issues such as blue-green algae, microbeads and microplastics.

Blue-Green algae

One issue the ministry continues to watch closely is how climate change and other factors such as changes in the quantity of nutrients entering Ontario’s waterways might affect the growth of blue-green algae. Ministry scientists are studying algal blooms to better understand them. Their work will contribute to actions needed to reduce their occurrence.

Blue-green algae, or cyanobacteria, are primitive organisms, some of which can produce toxins. This type of algae occurs naturally in lakes and rivers, but excessive growth of blue-green algae is a recognized problem in some areas of the Great Lakes, particularly western Lake Erie. When certain conditions are favourable, such as when the level of nutrients are elevated in calm water that receives lots of sunlight, they can form dense blooms, visible as surface scums. These blooms can also occur on inland lakes and rivers. Human activities can increase algal growth and worsen the impacts. Additionally, there is concern the effects of climate change are contributing to increases in blue-green algal blooms.

The number of blooms can vary from year to year due to a number of factors, many of which may be impacted by climate change such as warmer water temperatures and changing weather conditions. In 2016, as of November 24, blooms of blue-green algae were confirmed at 44 lakes or rivers in Ontario. These blooms may contain toxic algae, however the ministry has not detected microcystin-LR (algal toxin) in treated drinking water.

A comprehensive protocol is in place that entails rigorous, proactive and frequent monitoring of raw water by municipal water treatment plants to ensure early detection. Since 2014, Ontario has had a 12 Point Action Plan in place to prevent and respond to blue-green algal blooms and their impacts. Efforts are coordinated with partners, including municipalities and local medical officers of health, to improve scientific understanding and the importance of proactively monitoring local source water. These efforts included outreach to municipal drinking water system owners and operators.

Microplastics and microbeads

The ministry takes pride in its strong science in researching and monitoring emerging water issues such as microbeads and microplastics.

Microplastics are particles of plastic less than 5 mm in length or diameter. Microbeads are one form of microplastic which are often spherical and irregularly shaped particles used in personal care products such as face, hand, and body washes for exfoliating the skin. Other sources of microplastics include litter of plastic items and packaging, lines and fibres (from netting and textiles), polystyrene foam packaging and insulation, and cuttings from commercial plastics production and used in building materials.

Through its own research, monitoring, and work with others, the ministry is developing a better understanding of the sources of microplastics and their potential impacts. For example, from February 2014 to September 2016 the ministry partnered with the University of Western Ontario to sample for microplastics in sediment of the Great Lakes, finding greater amounts near urban centres where plastic products are made and used by the local population. The ministry has also partnered with the University of Toronto to examine the ingestion of different types of plastics by fish.

Ministry research is contributing to national efforts on understanding more about microplastics and the threats they pose to Ontario’s water. Ontario’s work on microbeads in personal care products contributed to the size range adopted in Environment and Climate Change Canada’s definition of microbeads. There is now a global timeline as companies have begun to phase out plastic microbeads from personal care products and will continue to do so through 2017 prior to planned bans in 2018 in Canada and the United States. Ontario recognizes that action on plastic microbeads is an important step in addressing a broader problem of microplastics accumulating in our lakes and rivers, and that there are a range of solutions that will need to be applied to reduce microplastics in the environment over the longer term.

Monitoring water quality

Monitoring the quality of water provides scientific information that can help in better understanding the state of Ontario’s drinking water, changes resulting from climate change and issues for the future. To this end, every year the ministry collects and analyses tens of thousands of water, sediment and aquatic life samples that have proven to be critically important for setting standards.

The ministry’s Drinking Water Surveillance Program is a prime example of science in action. It has been monitoring Ontario’s drinking water for 30 years, collecting data on more than 300 contaminants. It’s a rich source of information on contaminants in both source water and drinking water.

In March 2016, Ontario released the Water Quality in Ontario 2014 Report. This fourth biennial report includes research that demonstrates how multiple issues, such as climate change and other environmental stressors, can have a cumulative impact on water quality conditions. The report is part of Ontario’s strategy to increase awareness of actions to restore and protect water in the province.

Understanding these cumulative effects is a current focus area for the ministry’s water monitoring programs and key to targeting actions needed to restore and protect water in Ontario now and in the future.

The research presented in the water quality reports over the years has shown that through collaboration, measurable success in cleaning up contaminated areas has been realized. Ontario has cleaned up toxic hot spots in Collingwood Harbour, Severn Sound and Wheatley Harbour (near Leamington) and is closer to restoring sediment quality at Peninsula Harbour (near Marathon).

Final thoughts

Water is essential for our communities, our economy and for life. One of the biggest challenges we will have to overcome to protect the quality and quantity of our water is climate change, perhaps the most defining issue of our time.

This year we made progress in our scientific understanding of the link between the effects of a changing climate and water. Ontario will continue to work with partners to understand trends that may impact its water. Every year we learn more about how to protect our water and every year with our partners, we’re putting this knowledge to work.

The actions we are taking on climate change puts us on a path to a prosperous, low-carbon society. We’re reducing emissions, protecting drinking water sources and applying new science and knowledge to challenges such as blue-green algae and microplastics.

We’re making progress on collaborating with Indigenous communities in a new relationship based on reconciliation and respect for traditional knowledge, to improve drinking water on reserves and train and certify the experts needed to protect water at source.

We’re working with communities and partners, across the province, across Canada and internationally, contributing our scientific expertise to make a positive difference.

Thanks to your help and commitment too, we are making a difference, by making sure our water is protected — for now and generations to come.

Footnotes

- footnote[1] Back to paragraph Washington State University. "Climate change rapidly warming world’s lakes: More than half world’s freshwater supplies measured." ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 16 December 2015. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2015/12/151216174555.htm

- footnote[2] Back to paragraph Ontario Ministry of the Environment. Climate Change: Climate Change Progress Report. 2012. PDF. Pg. 9.