Quetico Provincial Park Management Plan (Published 2018)

This document provides direction on the management of Quetico Provincial Park.

ISBN 978-1-4868-1136-6 Print

ISBN 978-1-4868-1137-3 HTML

ISBN 978-1-4868-1138-0 PDF

© 2018, Queen’s Printer for Ontario

Printed in Ontario, Canada

Additional copies of this publication can be obtained from the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry Ontario.ca website

And

Quetico Provincial Park

108 Saturn Avenue

Atikokan Ontario

P0T 1C0

Telephone:

Planning questions can be addressed to:

Superintendent,

Quetico Provincial Park

108 Saturn Avenue

Atikokan Ontario

Ontario Parks

Northwest Zone Office

Suite 221d 435 James St. S.

Thunder Bay, ON P7E 6S8

Cette publication hautement spécialisée Quetico Provincial Park Management Plan n’est disponible qu’en Anglais en vertu du Règlement 671/92 qui en exempte l’application de la Loi sur les services en français. Pour obtenir de l’aide en français, veuillez communiquer avec Michele Proulx au ministère des Richesses naturelles et des forêts au

Lac La Croix First Nation

Neguaguon Lake I.R. 25D

Greetings! We would like to say thank you to the parks management team for allowing us the opportunity to contribute to the Park Management Plan. A community process was followed to add Lac La Croix First Nation’s voice to the plan. We appreciate the opportunity and thank everyone involved in the process.

We listened to many great stories and teachings from our elders during this time helping to bridge the gap between the Quetico Park Personnel and Lac La Croix park employees. This exercise has brought us closer to realizing the dream of working together as equal partners and strengthening our relationship. Because of this exercise unity, strength, and wisdom from both sides are now entrenched in this plan. Lac la Croix takes great pride in providing their expertise, knowledge and feedback to the plan.

Realizing that both parties have a vested interest in the Park lands, we must never forget that it has always been the Anishinaabe people caring for their homelands since time immemorial. Our hunting, fishing and ceremonial rights on these lands provide us with our way of life, given to us by the Creator. Our ancestors have always shown their sacred ceremonies upon these lands and still do so today. We are one with the land and will do our part in taking care and nurturing it for future generations to enjoy. We believe the laws given to us by our Creator are the laws we Anishinaabe people must follow. We have inherent rights and obligations to the land since time immemorial and a long history of ancestors on these lands. We are forever connected spiritually to the land, these are our beliefs and who we are.

We must also never forget about the Sturgeon Lake Band, also known as 24C, where our relatives were forcibly removed to make way for the creation of Quetico Park. A public apology was made by then Minister of Aboriginal Affairs, Bud Wildman, for this great injustice. The knowledge of reserve 24 C still has a place in our hearts and the pain, suffering, trauma and emotional scars are ever present. For most of us it remains difficult to talk about it and instills in us our strong commitment to be equal managers of Quetico Park. There are still significant spiritual and cultural ties to the land there, especially with the wild medicines that can only be found there and also for our elders that have passed on who had shared their stories from there.

The pristine waters, good quality fresh air, awesome old trees making way for young ones, beautiful waterfalls, nice sandy beaches, mysterious caves, great fish and all the animals and insects and plants are naturally occurring elements that provide for our people. These Naturally existing elements give us our medicines, food, water and way of life, as they have been, since we were placed here, to sustain us. We want to welcome all our park visitors to experience and share the park lands and all it has to offer as we have been doing since the beginning. These are indeed great and majestic lands, full of life, freedom and wonders. It is our serene and powerful home that we protect and share. The people of Lac La Croix open their hearts and spirits for the visitors of Quetico Park to enjoy everything the park offers as our ancestors did.

This Park Management Plan was written with the voice of Lac La Croix. This reassures that Lac La Croix, Anishinaabe Nation will always be there to help protect the park, as it is our homeland. Just like our leaders before us the land of Quetico Park hold a strong cultural, spiritual meaning that will always be present and must be respected. Quetico Provincial Park sits on our traditional territory and we are very happy and honored to work and manage this land together.

Norman Jordan

Chief of Lac La Croix First Nation

Approval statement

I am pleased to approve the Quetico Provincial Park Management Plan as the official policy for the management and development of this park. The plan reflects the intent of the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, Ontario Parks to protect the natural values and cultural heritage resources of Quetico Provincial Park and to maintain and develop opportunities for high quality ecologically sustainable outdoor recreation experiences and heritage appreciation for the residents of Ontario and visitors to the province. The plan includes the invaluable contributions of the Lac La Croix First Nation that reflect their deep relationship to the park lands and waters and to the spirit of shared resource decision making for Quetico Park.

This document outlines the site objectives, policies, actions and implementation priorities related to the parks’ natural, cultural and recreational values and summarizes the involvement of Indigenous communities, the public and stakeholders that occurred as part of the planning process.

The plan for Quetico Provincial Park will be used to guide the management of the park over the next 20 years. During that time, the management plan may be examined to address changing issues or conditions, and may be adjusted as the need arises.

I wish to extend my sincere thanks to all those who participated in the planning process.

Yours truly,

Bruce Bateman

Director, Ontario Parks

Context

Planning context

This park management plan has been prepared consistent with direction contained in the Strategic Directions for MNRF Aboriginal Relations (2010); The Ministry’s strategic direction Horizons 2020 (2015); Biodiversity: It’s In Our Nature (OMNR 2012) and in Ontario Provincial Parks: Planning and Management Policies (OMNR 1992). Additionally, Quetico Provincial Park will be managed to protect any species at risk and their habitats in a manner consistent with the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA) and regulations.

Ontario, as the Crown, has a legal obligation to consult with Indigenous peoples where it contemplates decisions or actions that may adversely impact the existence of credibly asserted or established Aboriginal or treaty rights. Ontario is committed to meeting its duty to consult with First Nations and Métis communities. The duty to consult and, where appropriate, accommodate is rooted in:

- the Honour of the Crown (a legal principle that commits government to act with integrity)

- the protection of Lac La Croix First Nation and treaty rights under section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982

All activities undertaken in Quetico Provincial Park must comply with A Class Environmental Assessment for Provincial Parks and Conservation Reserves (Class EA-PPCR; OMNR 2005b), where applicable.

Anishinaabe Peoples

This management plan does not affect Aboriginal or Treaty Rights and associated traditional uses.

Quetico Provincial Park is located within the boundaries of lands covered by the Treaty #3 area. All communities of Treaty #3, including, Lac La Croix First Nation (LLCFN), Seine River First Nation, and Lac des Mille Lacs First Nation and others have an established claim to inherent rights as set out in Treaties and by virtue of their proximity to Quetico Provincial Park.

Métis peoples

Quetico Provincial Park is located in proximity to three Métis Nation of Ontario (MNO) asserted harvesting territories. The closest modern day Community Councils that may have an interest include Northwest (Dryden), Kenora, Sunset Country (Fort Frances) including the Atikokan and Area Métis Council.

In recognition of the Anishinaabe cultural and any other archaeological features located within the park, Ontario Parks will have special regard for local particular interests. Respect and protection of cultural values are integral to this park management plan. Anishinaabe and Métis communities will be consulted on related issues of concern during the implementation of this plan.

Lac La Croix and the Agreement of Coexistence

A major amendment to the park management plan was initiated by the Lac La Croix First Nation in 1992 to temporarily expand the number of lakes permitting motorized access by the Lac La Croix Guides Association (LLCGA), which resulted in the Agreement of Co-existence (1994) and the Revised Park Policy (1995). This agreement between the Lac La Croix First Nation and the Province of Ontario, represented by the Minister of Natural Resources and the Minister for Native Affairs, was intended to redress the First Nation for their displacement from their traditional homeland and loss of economic opportunities and to work towards the provision of opportunities for employment and economic diversification.

The Agreement of Co-existence established a framework for long-term employment targets, spiritual and cultural use of Quetico, management and interpretation of Anishinaabe resources, co-management of mechanized guiding activity, and year-round road access to the First Nation community. Key elements of the agreement included creation of a mechanized guiding zone for members of the Lac La Croix Guides Association (LLCGA) (Wilderness Zone 2) to be co-managed with Lac La Croix First Nation; relocation of the Lac La Croix entry station to the community of Lac La Croix; and a commitment to open communications between Lac La Croix First Nation and Quetico Provincial Park.

Since 1995, this agreement has facilitated the development of a work centre and park entry station at the Lac La Croix community. It has also provided yearly funding which the band uses to support staff positions at the village work centre/entry station, at the Beaverhouse entry station, as well as an interior portage maintenance crew. Park warden and natural heritage education positions have also been funded. See Appendix A for the governing principles of the Agreement of Co-existence.

Lac La Croix First Nation and Quetico

In a message to Quetico Provincial Park visitors, Lac La Croix First Nation’s Leadership share the origin of the park’s name.

The Name Quetico comes from the Ojibway word, “Gwetaming”. This refers to how we view this sacred land. There is a place in the park that is named Quetico Lake. The lake is sacred, meaning it is occupied by living spirits that have been here since time immemorial. You hear stories from our elders of unexplained and unusual events at this lake, which can only be explained by our spiritual ways. The Lake is very spiritual and sacred to us. We are told to be mindful and respectful of the power it holds. “Gwetaming” means we sacredly respect that area for the spirits that dwell there.”

Quetico is the land upon which much Lac La Croix First Nation’s rich history has played out long before the creation of the park. For centuries, Anishinaabe people lived, raised families, conducted ceremonies, travelled and harvested on the land. It is not until relatively recently that Lac La Croix First Nation and Quetico began to share a history that has spanned the lifetime of the park. Quetico is a part of Lac La Croix First Nation’s traditional territory and homeland. In 1887 The Sturgeon Lake Indian Reserve 24C was surveyed on the east side of what is today Quetico. The Sturgeon Lake Band settled on the reserve until it was declared cancelled by the Province in 1915, two years after the creation of the park. After this cancellation, families were removed from 24C by the government, but neither the Sturgeon Lake Band nor the memory of its land have been totally erased. Today, Lac La Croix, Seine River and Lac De Milles Lacs First Nations all have members who are descendants of the Sturgeon Lake Band. The connection to 24C remains strong to this day. Lac La Croix First Nation continues to care for the Community Drum and Treaty Medallion of the Sturgeon Lake Band that lived at 24C. When the land that was the traditional territory of Lac La Croix First Nation and Sturgeon Lake First Nation was transferred from Canada to Ontario, neither First Nation was consulted. When Quetico Provincial Park was first regulated in 1913 by the Ontario government, once again neither Lac La Croix First Nation nor Sturgeon Lake First Nation were consulted. In the years after the creation of the park, members of Lac La Croix First Nation endured numerous injustices. First Nation members were prevented from accessing sacred places, trap lines were disturbed, and access to the park for hunting, fishing and trapping was denied. These and other imposed land use restrictions contributed to the economic hardships of the isolated community.

On Monday June 3, 1991, the Minister Of Natural Resources made a public apology to Lac La Croix First Nation which set in motion changes to the Park Management Plan of the time, including the recognition of lakes set aside for motorized guiding for Lac La Croix Fishing guides, This in turn led to the 1994 Agreement of Co-existence (AOC) between Lac La Croix First Nation and the Province. As a result of the AOC and the openness of Lac La Croix First Nation to work in partnership with Quetico, a number of developments have taken place from 1994 onwards that have helped to improve the relationship. Lac La Croix took on the management and operation of a large portion of the park as a part of the AOC. The number of motorized guiding lakes for the Lac La Croix Guides has increased, and many other shared initiatives have been undertaken to bring the parties closer together and improve the social and economic condition of Lac La Croix First Nation.

Provincial Parks and Conservation Reserves Act

The Provincial Parks and Conservation Reserves Act, 2006 (PPCRA) is the legislation that guides the planning and management of the protected areas system. The PPCRA has two specific principles that guide all aspects of planning and management of Ontario’s system of provincial parks and conservation reserves:

- Maintenance of ecological integrity shall be the first priority and the restoration of ecological integrity shall be considered

- Opportunities for consultation shall be provided. 2006, c. 12, s. 3

The PPCRA requires that management direction be prepared for each protected area in Ontario. This plan fulfils this requirement, and provides the long term direction for managing the protected area, including the purpose and vision, objectives, zoning, protected area policies and implementation priorities. This management plan is written with a 20 year perspective in mind.

Ecological integrity

The PPCRA defines ecological integrity as follows:

“Ecological integrity refers to a condition in which biotic and abiotic components of ecosystems and the composition and abundance of native species and biological communities are characteristic of their natural regions and rates of change and ecosystem processes are unimpeded.”

Ecological integrity addresses three ecosystem attributes – composition, structure and function. Ecological integrity is based on the idea that the composition and structure of the protected area should be characteristic for the natural region and that ecosystem functions should proceed normally. In other words, ecosystems have integrity when they have a mixture of native living components (plants, animals and other organisms), non-living components (such as rock, water and soil), and processes (such as reproduction and population growth) and the interactions between these parts are not disturbed (by human activity).

Management direction describes the contribution(s) that a protected area makes to achieve the objectives and principles set out in the PPCRA, and identifies site-specific management policies intended to maintain or where possible, restore ecological integrity.

1.0 Introduction

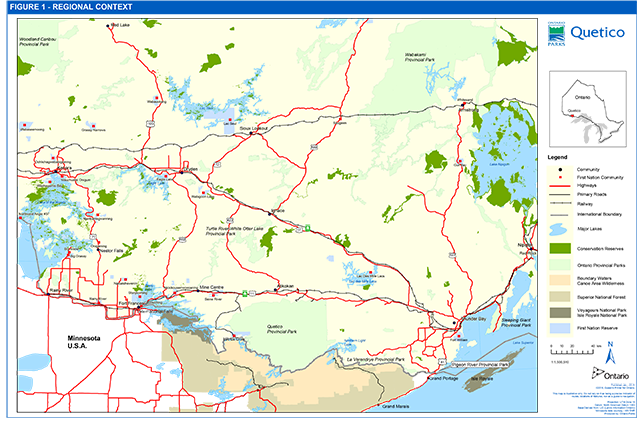

Quetico Provincial Park is located in the judicial district of Rainy River and within the Fort Frances District of the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry (MNRF). Quetico Provincial Park encompasses 4718 km2 (471,878 hectares) of rugged Canadian Shield with numerous lakes and streams. Quetico is located in northwestern Ontario, south of the town of Atikokan, approximately 160 km west of Thunder Bay and adjacent to the Canada -United States (U.S.) boundary (see Figure 1 for regional context). The park occupies a zone of transition between the boreal forests to the north, the mixed forests to the south and the Great Plains forests to the west and southwest. The southern boundary of the park lies on the Canada - U.S. boundary, the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness (BWCAW) within the Superior National Forest, while Voyageurs National Park abuts the international boundary just to the west of Quetico. These American protected areas share recreational and interpretive themes with Quetico (Figure 1). In 1996, the Canadian side of the waterway along the international border was also designated by the Canadian federal and Ontario provincial governments as part of the Boundary Waters-Voyageur Waterway, a Canadian Heritage River.

Seine River First Nation is located roughly 30 kilometres west of the Quetico park western boundary. As of November 2017, the First Nation had a total registered population of 780, of which 351 lived on reserve. Reserve lands are in three parcels - Seine River 23A, Seine River 23B and Sturgeon Falls 23. The Seine River First Nation is home to the Grey Raven Ranch, a non-profit organization whose mission is to help the community’s youth develop confidence and leadership skills by entrusting them with the care of the Lac La Croix Indian Ojibway pony herd.

Lac des Mille Lacs First Nation is a signatory to Treaty #3 under the Shebandowan-Adhesion in 1873. The First Nation is the furthest east of the communities within the Treaty #3 territory. The current population of registered Band Members is 603. The First Nation is comprised of two separate and distinct parcels of land, one being Lac des Mille Lacs First Nation Reserve 22A1 (Farmlands) located on Lac des Mille Lacs approximately 135 km west of Thunder Bay and the other being Lac des Mille Lacs First Nation Reserve 22A2 (Wildlands) located on the banks of the Firesteel and Seine Rivers, approximately 20 km west of Upsala. The Ojibway name is Nezaadiikaang, which means Place of the Poplars. Reserve 221A is approximately 50 kilometres east of the Quetico park eastern boundary.

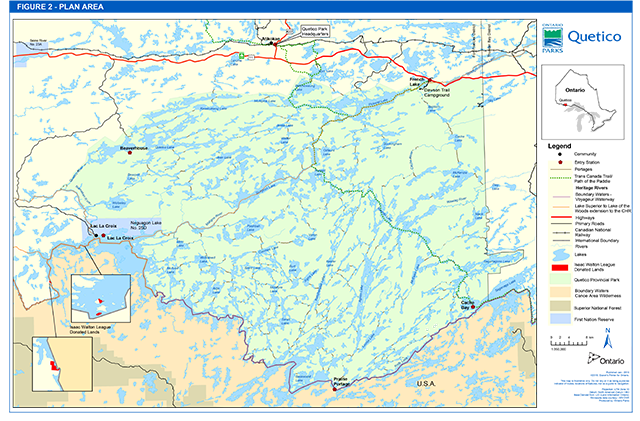

The community of the Lac La Croix First Nation, known as Zhingwaako Zaaga’iganing (Lake of the Pine Trees or Pine Tree Lake) abuts the southwest boundary of the park, where it spans 62.1 km2 along the northern shore of Lac La Croix (INAC 2005). This community of approximately 350 people is home to the Lac La Croix First Nation, and serves as a western administrative area for the park (see Figure 2 for local context).

Figure 1 Regional context

Expand Figure 1 Regional Setting

Figure 2 Plan area

The Township of Atikokan with a population of 3,000 is located immediately north of Quetico, and serves as base for park administration.

In 1909, Quetico Forest and Game Reserve was established to protect wildlife values. Earlier that same year, in the adjacent American state of Minnesota, the Superior National Forest was founded to enhance forest management. Quetico Provincial Park was regulated as a provincial park in 1913, and was classified as a wilderness park in 1977. There are no commercial tourism facilities located within the park boundaries, with the exception of a facility on private land used for commercial tourism on Batchewaung Lake. Quetico has had a management (master) plan in place since 1977 which has been reviewed and updated regularly (1982, 1988, and 1995). The park’s abundant waterways, rich cultural history, wild undeveloped landscape and relative lack of mechanized travel, all contribute to its reputation as an area of unparalleled wilderness canoeing opportunity (Figure 2).

The PPCRA, which governs activities within provincial parks, applies only to lands and waters within the regulated boundaries of parks and conservation reserves. Ontario Parks is committed to an ecosystem approach to park planning and management. This approach allows park managers to consider the relationship between the park and the surrounding environment. Park managers may consider potential impacts on park values and features from activities occurring on adjacent lands, and potential impacts from park activities on land uses in adjacent areas.

Park management plan policies apply only to the area within the regulated boundary of the park. Within the park boundary, the protection of park values and features will be achieved through appropriate zoning, control of land use and activities, education, and monitoring of ecological impacts.

Quetico Provincial Park is governed by Ontario’s PPCRA, Ontario Provincial Parks: Planning and Management Policies (OMNR 1992a) and Ontario’s Living Legacy - Land Use Strategy (OLL-LUS; OMNR 1999).

2.0 Classification

Through park classification, Ontario’s provincial parks are organized into broad categories, each of which has particular purposes and characteristics.

Quetico Provincial Park is classified as a wilderness park. The class target for wilderness parks is to establish at least one in each of Ontario’s 13 ecoregions. Quetico Provincial Park fulfils the representation target for wilderness class parks in ecoregion 4W. As a wilderness park, Quetico’s primary emphasis will be protection. The classification does not affect Treaty #3 communities, including Lac La Croix First Nation Aboriginal or Treaty Rights. The wilderness classification will also honour the deep spiritual sacrosanct connection with the land that is the cultural heritage of Lac La Croix First Nation.

Quetico Provincial Park is currently an operating park. A park operations plan has been prepared to provide park staff with the necessary direction to operate the park on a day to day basis. In addition to addressing the operations policies that follow, the plan includes such topics as budget, staffing, maintenance schedules, enforcement, education, and emergency services. The provisions of the plan will be consistent with the approved Ontario Provincial Parks Minimum Operating Standards, and will be reviewed annually and updated as required.

The operating status of provincial parks is determined by Ontario Parks based on visitation and use, analysis of revenue and expenditures, and infrastructure needs. Changes to a park’s operating status may be made by Ontario Parks without the provision of external involvement.

3.0 Vision

The vision for Quetico Provincial Park is:

3.1 Lac La Croix First Nation and its relationship with Quetico Park

An Agreement of Co-Existence negotiated in 1994 between the government of Ontario and the Lac La Croix First Nation, frames this relationship. The substantive elements of that agreement provided the basis for amendments to the 1995 plan and it continues to provide direction in this plan. As of 2015, the Agreement of Coexistence is undergoing a joint review. If a renewed agreement is finalised it will also provide direction to this plan and if necessary a plan amendment will be undertaken to address any new direction.

4.0 Objectives

Quetico will be planned, managed and operated as a wilderness park in accordance with the PPCRA: “The objective of wilderness class parks is to protect large areas where the forces of nature can exist freely and visitors travel by non-mechanized means, except as may be permitted by regulation, while engaging in low-impact recreation to experience solitude, challenge and integration with nature.” 2006, c. 12, s. 8 (2).

There are four objectives for Ontario’s provincial parks: protection, recreation, heritage appreciation and scientific research. Each park in the system may contribute in some way to each of these objectives, depending on its resource base. Quetico Provincial Park contributes to the achievement of all four objectives.

4.1 Protection

Ontario’s protected areas play an important role in representing and conserving the diversity of Ontario’s natural features and ecosystems across the broader landscape. Protected areas include representative examples of life and earth science features, and cultural heritage features within ecologically or geologically defined regions. Ontario’s ecological classification system provides the basis for the life science feature assessment, and the geological themes provide the basis for earth science assessment.

The protection objective will be accomplished through appropriate park zoning, resource management policies, research, and monitoring.

4.1.2 Earth science

Bedrock geology

Quetico Provincial Park lies on the southwestern portion of a vast area of ancient rock known as the Canadian Precambrian Shield (the Shield). The Shield forms the foundation of the North American continent and consists of some of the oldest rocks on earth. It is divided into provinces and subprovinces on the basis of overall differences in internal structural trends, age, lithology (rock types), metamorphic grade (alteration) and style of folding (Thurston 1991). Quetico Provincial Park lies within the Superior Structural Province of the Shield, and encompasses portions of two subprovinces, the Wawa Subprovince in the southeastern portion of the park, and the Quetico Subprovince in the remaining portion of the park. All the rocks within the park boundaries are of Archaean age, having last been affected by a major period of mountain-building during the Kenoran Orogeny some 2 700 to 2 500 million years before present.

A sedimentary-volcanic sequence known as the Poohbah Lake Complex is located at Poohbah Lake. It is an alkaline intrusive sequence comprising syenite and nepheline syenite associated with sheets of leucogranite. The complex is significant in that it is one of the oldest known alkaline intrusives in the Shield, with an age of some 2 700 million years (Williams 1991). The type locality

Two thirds of the park is underlain by granite, an acidic bedrock that results in a low variety of plant species and clearer, less productive lakes. Two larger areas of metasedimentary bedrock, one in the east and one in the west, result in soils that are deeper and richer with a higher diversity of plant species. In the southeast corner of Quetico is an area of metavolcanic bedrock, also referred to as greenstone. In contrast to the acidic soils of the granitic area, soils and lakes in this area tend to be basic due to the higher levels or calcium. Plant diversity is much higher and lakes tend to be more productive when compared to lakes in the rest of the park.

Surficial geology

In the Quetico area, the Wisconsinan Stage was witness to many advances and retreats of the continental ice masses, though only the features associated with the last of these, the Late Wisconsinan, are preserved. The ice withdrew from the area of the park for the last time about 11 000 years before present as the ice front stabilized briefly along the Steep Rock Moraine and the subsequent Eagle-Finlayson Moraine. Glacial Lake Agassiz was in contact with the ice margin along its northern shoreline, and covered most of the low-lying areas in the Rainy River valley (Barnett 1992).

Glacial and postglacial features and landforms left behind by the last glacial retreat in the park include two sets of glacial striae, reflecting local variations in the movement of the ice, segments of two recessional moraines (a type of end moraine) associated with ice-halt positions during the retreat of the final ice sheet, raised shoreline features and lacustrine deposits of glacial Lake Agassiz, and bare to sporadically mantled bedrock, the result of wave-washing of the Shield by the waters of glacial Lake Agassiz. The predominant surficial deposit in most of the park consists of a thin, discontinuous mantle of sandy till deposited as a ground moraine.

4.1.3 Life science

Quetico Provincial Park has a number of life science features that are of ecological, interpretive and educational significance. A number of significant communities are found in Quetico. These communities are of interest for a number of reasons. Some of the communities are biologically diverse, contain high levels of rare species, or are of value to the Natural Heritage Education (NHE) Program.

Quetico Provincial Park is situated in ecodistrict 4W-1, within the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Forest Region, and borders the Boreal forests to the north and the Great Plains forests to the west and southwest. As a result, Quetico is characterized as containing a mixture of mostly northern, as well as some southern and western elements, resulting in a diversity of plant species typical of the different regions. To date, 666 plant species have been identified in the park, the majority of which are terrestrial. The aquatic plant community has not been sampled to the same degree, and there are likely many more plant species still to be recorded.

Efforts will be made to enhance protection of species at risk and to prevent and /or mitigate the introduction of invasive species.

Red and white pine communities

Although white and red pine trees are widely distributed throughout the park, large stands where they are the dominant species are relatively rare, making up about 10% of Quetico’s forest. Red and white pine stands are most common in an area from McAree to Kahshahpiwi Lake in the south of the park and from Sturgeon to Pickerel Lake in the north. A significant area of old white and red pine occurs in the vicinity of McNiece and Shan Walshe Lake. These forest communities are also significant for their fire research and natural heritage appreciation values.

Eastern white cedar communities

Extensive stands of eastern white cedar are largely absent from the majority of the park, but can be found on greenstone bedrock in the southeast corner of the park. Many of these communities are significant as old growth features. One significant old growth eastern white cedar community is found on Emerald Lake. Associated ground flora includes false Solomon’s seal, dwarf horsetail and blunt-leaved orchid. Another significant eastern white cedar community is located near Belaire Lake. This community is a pure cedar stand situated in a depression on metamorphic bedrock. Two southern species found here are jack-in-the-pulpit and blunt-leaved orchid, both of which are abundant here but locally rare.

Hardwood forest communities

A rich trembling aspen community on clay soil is found on Wolseley Lake. Because deep pockets of clay are rare in Quetico, the floristic diversity at this site is locally significant. Components of the community are Saskatoon berry, black snakeroot, white rattlesnake-root and purple oat.

Two forest communities that contain large red maple have also been identified. In the area between Poohbah and Berniece Lakes, the forest community is dominated by white birch and trembling aspen with an abundance of large red maple. Pure stands of red maple are found in the vicinity of Glacier Lake, where the red maple stands are smaller inclusions within a trembling aspen forest. These hardwood forests are rare in Quetico. In addition to their ecological value, they also have a high value for education and research purposes.

Mixedwood forest communities

A significant white pine and yellow birch forest community exists along the portage between Lindsay and Cache Lakes. This is the best and largest example of this community type found in the park to date. Yellow birch is locally rare in the park, and can only be found throughout the park as minor inclusions in other forest types.

Red oak is a hardwood species that is locally significant. In the park it is found in mixed forest communities, usually growing in association with red pine. Red oak is fairly abundant along the Maligne River and in the red pine stands in the Shan Walshe Lake area.

Open wetland communities

A number of bog communities in Quetico support locally rare orchid species. Swamp pink orchid and rose pogonia have both been documented at two bogs in the vicinity of Bearpelt Lake and Star Lake. Walshe (1980) noted that the Bearpelt Lake bog is significant as every stage of bog development can be found here.

Rich marsh communities are rare in Quetico. Bearpelt Creek Marsh is an extremely rich marsh and contains the only local occurrence of pickerel weed. Rich wetland communities are important for the high level of biodiversity present, and are also important moose aquatic feeding areas and provide important habitat for waterfowl.

Shoreline communities

Significant open shoreline communities that support prairie species exist along Lac La Croix in Martin and Rice Bay, and on Iron Lake. Locally rare freshwater cordgrass is generally found growing close to shore, with big bluestem growing higher on the shore in drier soils.

Floodplain communities

The physiographies of the Wawiag and Cache River floodplains are extremely rare in Quetico and northwestern Ontario. Deep glaciofluvial outwash and alluvial deposits of sands and gravels were deposited here when glacial Lake Agassiz occupied the area. In later, quiet-water times of the lake, silts and clays were periodically deposited in association with the nearshore and outwash sediments, creating an extremely fertile alluvium.

The floral diversity of the Wawiag River floodplain is perhaps greater than anywhere else in Quetico, with many southern and western species present. Near the mouth of the Wawiag at Kawa Bay, a silver maple community with white elm is found on the narrow levee. Fringed loosestrife and sessile-leaved bellwort are abundant in the herbaceous layer. Hawthorn spp. and chokecherry are co-dominant, with nannyberry and highbush cranberry common associates. Hops are also present at this site, found growing on the upright shrub species. Locally rare herbaceous species found in this forest community include smooth carrion flower, ostrich fern, and cow parsnip.

Within Kawa Bay, the provincially rare red-disked water lily is abundant, growing in association with softstem club-rush, river club-rush, and narrow-leaved floating burreed.

Farther upstream from this site at the Mack Creek junction is a white elm and red ash community with Manitoba maple occurring as a minor component. Wild ginger is found in this community and it is the only one of two known locations of this species in the park.

A number of significant floodplain communities exist along the Namakan River. A red ash – silver maple stand with bur oak can be found along the shoreline. Herbaceous flora associated with this community include: poison ivy, royal fern, small sundrops and sand cherry. Located behind the red ash - silver maple community is a trembling aspen – white elm community with a large component of basswood, bur oak and red maple. Associated with this community are many southern herbaceous plants including: sessile-leaved bellwort, carrion flower, false Solomon’s seal, and jack-in-the-pulpit, downy yellow violet and alternate-leaved dogwood.

Cliff communities

Provincially rare basic cliff communities are found along the Man Lakes Chain, Emerald and Ottertrack lakes and on a tributary of the Wawiag River. Other basic cliffs may exist in the park, but have not been reported to date. The Basic Open Cliff Type is provincially rare and ranked S3S4 (Bakowsky 2002).

Most of the basic cliffs in the park are covered in the calcium loving orange lichen, making identification of these cliff types quite easy. The north-facing Emerald Lake cliff community has a cooler than normal microsite that supports many arctic disjunct species including smooth cliffbrake, encrusted saxifrage, smooth woodsia, as well as two provincially rare species, limestone oak fern and snowy cinquefoil. Maidenhair spleenwort is also found at this location, and is only one of two known locations in the park. The other location is at a cliff found at the narrows on Agnes Lake, where the provincially rare limestone oak fern is also found. Disjunct northern and western plant species have persisted at these cliffs for thousands of years.

Mammals

Forty-three mammal species have been recorded to date in the park, representing 61% of Ontario’s mammal list (excluding non-native and marine mammals). Because of the relatively large size of Quetico Provincial Park and its position adjacent to the BWCAW, the combined protected area is able to support populations of species which require a relatively large home range and/or large portions of contiguous habitat. Such species found in Quetico include black bear, marten, and moose. Other large mammals found in Quetico include gray wolf, lynx, coyote and white-tailed deer.

Quetico Provincial Park contains the typical suite of small mammals for the area. A number of shrews, moles, bats, squirrels, voles, mice, and weasels can be found throughout the park. These include the northern short-tailed shrew, star-nosed mole, little brown bat, least chipmunk, woodchuck, woodland jumping mouse, deer mouse, meadow vole, southern bog lemming, red-backed vole, river otter and marten. Other species include fisher, porcupine, mink, red fox, and snowshoe hare.

Birds

As a result of Quetico’s transitional character, an overlapping of typically northern, southern, eastern and western species of birds occurs. Some representative species include: common raven, gray jay, black-backed woodpecker, black-capped chickadee, great gray owl, spruce grouse and many species of wood warblers, the Nashville, magnolia and mourning warblers being among the most common. Pine and evening grosbeaks, common redpoll, white-winged and red crossbills, pine siskin and purple finch are some of the very few bird species found in Quetico in the winter months.

Birds at the northern limit of their range include the black-billed cuckoo and indigo bunting while birds common to the western prairies such as the yellow-headed blackbird and western meadowlark have been observed. Quetico is known for its populations of bald eagle and osprey. All three accipiter species in Ontario are found in Quetico, including Cooper’s hawk, northern goshawk and sharp-shinned hawk.

Significant populations of waterfowl do not occur within the park. Common merganser, common goldeneye, black duck, mallard and common loon are the most common breeding species. Trumpeter swans have increased in Quetico over the past decade as a result of re-introduction efforts in Minnesota.

Reptiles and amphibians

Eight species of frogs, (including the northern leopard frog, wood frog, boreal chorus frog, and spring peeper), one species of toad (American toad) and two species each of salamanders (the eastern red-backed salamander and the blue spotted salamander), snakes (the common garter snake, and likely the red-bellied snake as it has been recorded in the Atikokan area) and turtles (the snapping turtle and the western painted turtle) have been recorded within the park. The western painted turtle is a subspecies of the painted turtle, and in Ontario this subspecies is only found in a narrow band in Northwestern Ontario along the Minnesota border. The snapping turtle is ranked as a species of Special Concern.

Fish communities

A total of 48 fish species have been reported in Quetico. The lakes within the park support fish communities that vary according to local lake characteristics. The broadest classification of these communities is according to coldwater and warmwater habitats. Coldwater communities can include lake trout, lake whitefish, cisco (lake herring), and burbot. Warmwater communities can include walleye, northern pike, smallmouth bass, largemouth bass, yellow perch, black crappie, rock bass, lake sturgeon

Invertebrates

Forty-nine species of moths and 31 species of butterflies have been identified to date in Quetico. Only one species has been designated a species at risk: the monarch butterfly is designated as Special Concern.

Dragonflies and damselflies are some of the more visible invertebrates in the park. Canada darners, dusky clubtail and chalk-fronted corporal are some of the most commonly encountered of the more than 50 dragonfly species in the park while river jewel and various species of bluet are frequently observed damselflies. The pygmy snaketail is a globally rare clubtail dragonfly ranked as a species of Special Concern. This dragonfly is known at only one location in Ontario at Lady Rapids on the Namakan River close to the western boundary of Quetico, where a single exuvium was discovered in June 2007.

4.1.4 Cultural features

Quetico Provincial Park contains a number of cultural features that are of historical and educational significance.

Respect for, and protection of, archaeological and cultural features is important to Lac La Croix First Nation as well as other Treaty #3 communities. Lac La Croix First Nation, and other communities have an established claim to inherent rights as set out in Treaties and by commitments made under Treaty #3 and by virtue of their proximity to Quetico Provincial Park; they will be involved in implementation of the plan.

The cultural heritage resources of Quetico Provincial Park are both plentiful and significant, representing major expressions of the Anishinaabe people of the boreal forest and Canadian Shield and their descendants, as well as Quetico’s role and importance to the fur trade period and to the exploration of Canada. Quetico’s rich archaeological past can be traced to its origins as part of the corridor between glacial lakes Agassiz and Minong through which the earliest inhabitants moved northeast as the glaciers retreated. The boundary waters corridor of Quetico has also been a major transportation route since the earliest times. The co-operation and partnership among the British fur traders, the voyageurs, and Indigenous people, including the Anishnaabe people, was a critical stage in the development of present day Canada, and international co-operation has been integral to the development and preservation of this extraordinary region.

The number of archaeological and pictograph sites found within the park reflects a high level of Anishinaabe, and earlier, peoples occupation (e.g., Paleo-Indian, Middle Shield, Woodland, Laurel and Blackduck cultures). The seasonally strategic lifestyle of the first inhabitants, the harsh terrain, and the acidic soils meant that relatively few small and scattered archaeological sites have been located (Dawson 1983, Wright 1995). The sites are often destroyed by rising water levels, invading forests, and acidic soils (Dawson 1983, Wright 1995). As a result, it is likely that many more artifacts may have existed than have been found to date, but were unable to withstand the ravages of time. Many portions of the park have not been explored archaeologically and those that have been surveyed have only been subject to cursory testing and, on rare occasions, limited excavation. As a result, available information about the long period of occupation by Anishinaabe people is incomplete. The park superintendent may close areas to camping in consultation with Lac La Croix First Nation and other Treaty #3 communities in order to protect known cultural values such as sacred sites, ceremonial sites, and burial sites.

An Indigenous rare breed of horse known as the Lac La Croix Indian or Ojibway Pony has a long association with the Quetico area. This is an extremely hardy and intelligent breed that was used by the people of Lac La Croix and Bois Forte (in Minnesota) for hauling, logging, running trap lines and for transportation and other work in the winter. The last four surviving ponies were removed from the Lac La Croix community in the 1970s and a breeding program was established in the 1990s to save the breed. The Seine River First Nation has several of these ponies at the Grey Raven Ranch which is run as a non-profit to provide community youth with opportunities to work with the horses.

4.2 Outdoor recreation

In recent years, approximately 26,300 people visit Quetico each year, with 118,000 camper nights (# visitors X length of stay) spent in the park. Approximately 8,200 people visit the campground each year, resulting in 15,000 camper nights in the campground. Approximately 18,000 people visit the interior of the park each year, resulting in 103,000 camper nights. Since the last management plan review in 1995, there has been a gradual but steady decline in the number of interior park visitors. In 2014 there were 11,333 interior visitors and 2,786 campground visitors, as well as 1,581 day users.

A 2011 visitor survey indicates that in 2011 83% of park visitors were from the U.S. and 60% of interior visitors entered through the southern boundary of the park. The 2011 Quetico Provincial Park Interior Visitor Survey asked respondents to provide their entry point: 38% of visitors entered via Prairie Portage; another 20% of entries were associated with the Cache Bay Entry Station: these figures represent 58% of entries through the two southern entry stations and eight entry points. Dawson Trail and Atikokan accounted for 31% of all park entries via the northern entries with Pickerel entry point at 16%, Batchewaung at 8% and Cirrus Lake/Sue Falls/Baptism Creek at 7%. Beaverhouse entry station accounted for 9% of entries and Lac La Croix entry station accounted for 6%.

Outdoor recreation will be encouraged to the greatest extent possible without adversely affecting the park environment or visitor experiences.

4.2.1 Quetico interior

To provide high quality, low intensity, wilderness experiences by providing ecologically sustainable outdoor recreation opportunities for extended non-mechanized travel and associated activities throughout the park’s interior.

The interior of Quetico Provincial Park offers a variety of recreation opportunities, in an array of natural settings. Recreational activities in Quetico are limited to primitive forms of travel, as well as those activities that are associated and compatible with primitive travel. The types of non-mechanized travel provided for have only been those consistent within the historical context of the park. Permitted activities include:

- Canoeing/kayaking

- Camping (back country)

- Sport fishing

- Motorized guiding on designated lakes by members of the Lac La Croix Guides Association

- Nature Appreciation

- Photography/Painting

- Hiking

- Snowshoeing

- Cross-country skiing

4.2.2 French Lake and the Dawson Trail Campgrounds

To provide high quality, moderate intensity, threshold wilderness experiences by providing ecologically sustainable outdoor recreation opportunities/or non-mechanized travel and associated activities based from the Dawson Trail car campground and day-use facilities.

The recreation objectives will be achieved through appropriate park zoning; the identification of management policies to prevent any compromise of significant natural and/or cultural heritage values or the ecological integrity of the park; market research and monitoring; and mitigating impacts of recreational use. Permitted activities include:

- Canoeing/kayaking

- Camping (car camping)

- Roofed accommodation

- Sport fishing

- Nature Appreciation

- Photography/Painting

- Hiking

- Snowshoeing

- Cross-country skiing on groomed trails

- Bicycling (including mountain bikes) on park roads

- Day use activities

- Education programs

4.3 Heritage appreciation

To provide opportunities for structured and unstructured individual exploration and appreciation of the natural and cultural heritage of Quetico Provincial Park.

This objective will be achieved through the park’s Education Program, structured and unstructured individual park exploration, and through the efforts of other groups such as the Friends of Quetico Park, the Quetico Foundation, the Lac La Croix First Nation, Lac des Milles Lacs First Nation and Seine River First Nation. Education is discussed in Section 8.4.

4.4 Scientific research

To facilitate scientific research and to provide points of reference to support monitoring of ecological change on the broader landscape, as well as to enhance the historical record and to support the preservation of Anishinaabe culture.

Ontario’s provincial parks play an important role in the provision of places to undertake research activities to: provide a better understanding of park environments, contribute to appropriate park management practices and actions, to contribute to cultural and historic knowledge and to provide baseline ecological information that can be used to support ecological monitoring on the broader landscape.

Quetico Provincial Park provides many opportunities for research by Ontario Parks and other MNRF staff, Lac La Croix First Nation, academic researchers and the Quetico Foundation. Research is discussed in Section 8.7.

5.0 Boundary

Quetico Forest and Game Reserve was created in 1909. Quetico was regulated as a provincial park in 1913 and classified as a wilderness class provincial park in 1977.

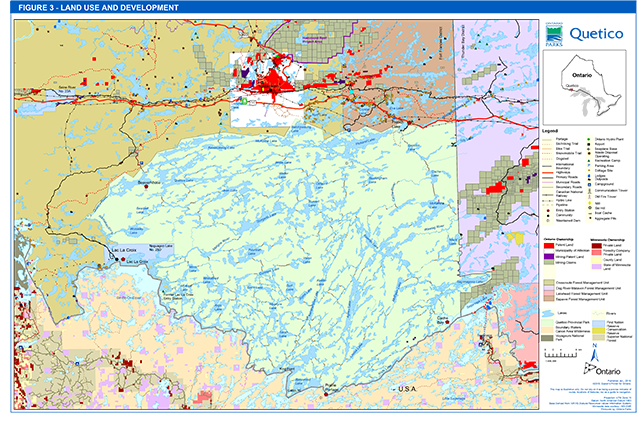

Park management plan policies apply only to the area within the regulated boundary of the park. Within the park boundary, the protection of park values and features will be achieved through appropriate zoning, control of land use and activities, education, and monitoring of ecological impacts (Figure 3).

Quetico Provincial Park surrounds several patent land parcels, totalling 74.26 ha in area. These lands are not subject to the PPCRA or park regulations. Many are the result of mining claims staked during and after World War II. As they become available, the titles to the mineral and surface rights for all mining claims, patents and licences of occupation located within the park will be acquired by the Crown. Lac La Croix First Nation will be notified when a piece of patent land reverts to the Crown or when Ontario moves to purchase a parcel that comes up for sale.

The Minister of Natural Resources, under the authority of Section 13(1) of the Public Lands Act, R.S.O. 1990, may designate any area in the unorganized territories of Ontario as a restricted area. As the designation grants MNRF significant control over activities on private land, restricted areas are created by regulation to ensure full oversight of the process. The construction of any building or structure or improvement in the restricted area requires prior approval by a permit issued by the MNRF. Current restricted areas surrounded by Quetico Provincial Park are listed in schedules 2 and 4 of O.Reg. 150/12. These restricted areas will continue to control development of private lands surrounded by the park.

Figure 3 Land use and development

Expand Figure 3 Land Use and Development

There are 3 Crown-owned properties (2 islands and a mainland parcel at Beatty portage) on Lac La Croix that were donated by the Izaak Walton League of America Endowment to Ontario in 1970 with the expressed purpose of wilderness protection (Figure 2). One island (parcel # CL 155) and the mainland parcel are regulated as Lac La Croix Wilderness Area under the Wilderness Areas Act. The other island (parcel # BG372) is included in the general use area (G2564). The reasons why this parcel is not included in the Wilderness Area will be investigated. Land use planning will be initiated for the Lac La Croix Wilderness Area and G2564. This process will determine whether these areas will be added to Quetico Provincial Park, or will be granted some other land use designation. Lac La Croix First Nation has expressed an interest in future land use planning for the three Crown patent properties donated by the Izaak Walton League.

The last park boundary adjustment occurred in 2014 when one parcel (64 ha) near Veron Lake was added to the park. This parcel (PIN 56067-0026) reverted to the Crown in 1936 for tax arrears. All forms of private land tenure surrounded by park will, in due course, be acquired by the Crown. Negotiations to acquire the remaining private land holdings will continue as funds and priorities permit.

A property plan will be prepared, approved and kept current for the park. It will provide guidelines for the acquisition, maintenance, operation and abandonment of all tenured land holdings.

6.0 Park zoning

Zoning is a key part of a park management plan. Zones fulfill a variety of functions that may include:

- Recognizing the features and attributes of a park;

- Delineating areas on the basis of their need for protection or their ability to protect provincially significant representative features;

- Delineating areas on the basis of their ability to support various recreational activities; and,

- Identifying uses that will protect significant features, yet allow opportunities for recreation and heritage appreciation.

Management of the park’s resources is consistent with policies in Ontario Provincial Parks Planning and Management Policies (OMNR 1992a) and OLL-LUS. To date, two types of zones have been employed to guide Quetico’s resource management, operations and development; central wilderness zones 1 and 2 (W1 and W2) and peripheral access zones (entry stations).

The W1 and W2 zones are being consolidated and renamed the W zone. Two additional zone types are being added in this plan. Historical and nature reserve zones include the French Portage cultural heritage zone, and the Wawiag River Floodplain and the Emerald Lake Basic Cliff Communities nature reserve zones.

6.1 Wilderness zone

Wilderness zones (W) include wilderness landscapes of appropriate size and integrity which protect significant natural and cultural features and are suitable for wilderness experiences, as well as a protective buffer with an absolute minimum of development.

Wilderness Zone 467,581 ha

The wilderness (W) zone, as shown in Figure 4, occupies all but about 4,279 ha of Quetico’s approximately 471,878 hectares. Because of its dominance within the park, the wilderness zone is the focus of the detailed policy outline as contained in the following sections. Development will be limited to back country campsites, portages, and trails. Wilderness campsites will offer limited facilities such as firepits. Box privies may be installed on sites close to entry points and on major travel routes that experience heavy use or where there is a risk to the environment.

The W zone is comprised of ninety-nine percent of Quetico’s land base, including all park lands not zoned as access, nature reserve or historic zones.

Two parcels of land, the first parcel formerly part of access zone A2, the second island of two islands at Cache Bay, and the second parcel a former part of access zone A4 at the end of the Beaverhouse access road, have been added to the W zone.

Management intent:

The revered qualities of Quetico, as identified in the park’s goal and objectives will be preserved in this zone. This wilderness zone will remain the domain of natural processes; the presence of the recreationist will be that of a privileged visitor, activities will be restricted to those not compromising the integrity of the biophysical base. Mechanized forms of recreational travel will not be permitted with the exception of the Lac La Croix Guides Association (LLCGA) under the guidelines listed in section 8.2.1.

A shared resource management decision making regime between Lac La Croix First Nation and the Quetico administration will be designed and implemented.

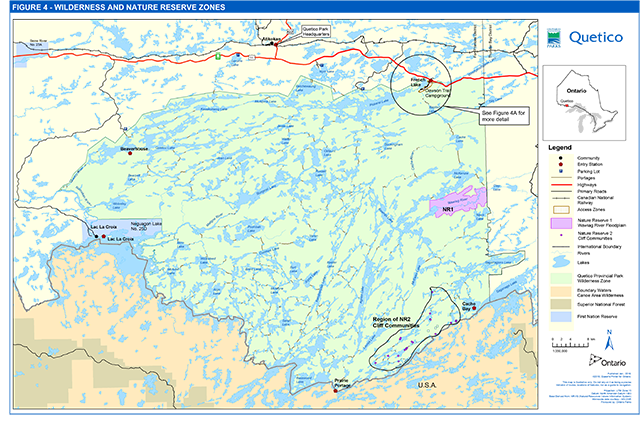

Figure 4 Wilderness and nature reserve zones

Expand Figure 4 Wilderness and Nature Reserve Zones

6.2 Nature reserve zones

Nature reserve zones (NR) include any significant earth and life science features which require management distinct from that in adjacent zones, as well as a protective buffer with an absolute minimum of development.

NR1 Wawiag River Floodplain 4,976 ha

The physiography of the Wawiag River floodplain is extremely rare in Quetico and northwestern Ontario. Deep glaciofluvial outwash and alluvial deposits of sands and gravels, silts and clays were deposited creating an extremely fertile alluvium. The floristic diversity of the Wawiag River floodplain is perhaps higher than anywhere else in Quetico, with a high number of southern and western species present. For a detailed description of this floodplain community refer to section 4.1.2.

NR2 Basic Cliff Communities 33 ha

Provincially rare basic cliff communities are found along the following lakes: Blackstone (1), Other Man (3), Ottertrack (10), This Man (3), Littlerock (2), Emerald (12), Fisher (1), Sheridan (1) and on a tributary of the Wawiag River. The Basic Open Cliff Type is provincially rare and ranked S3S4 (Bakowsky 2002). This zone is delineated as all of the cliff faces on the listed lakes.

Disjunct northern and western plant species have persisted at these cliffs for thousands of years. Since deglaciation, the surrounding vegetation has undergone drastic changes, while tundra and prairie plants were able to persist in open cliff habitats as the surrounding landscape became forested (Bakowsky 2002). For a detailed description of this basic cliff community refer to section 4.1.2.

Management intent:

The NR zone designation recognizes the fragility of these resources. Only scientific, educational and interpretive use is permitted in this zone. Some minimum impact recreational activity such as hiking is acceptable, provided there is no potential for features to be impacted. Development is limited to trails, directional and interpretive signs and temporary facilities for research and management.

Rock climbing and scrambling, back country camping, and mechanized travel are not permitted in nature reserve zones. Existing campsites in nature reserve zones will be closed and rehabilitated. Commercial trapping in NR zones by Lac La Croix trappers is permitted. Designation of nature reserve zones does not affect Aboriginal or Treaty Rights and associated traditional uses such as camping, hunting, fishing and harvesting medicines.

6.3 Historical zone

Historical zones (HI) encompass the provincially significant cultural resources of a park. They generally focus on a specific site (e.g., area of human occupation site, building(s)) and that site’s relationship to the surrounding landscape, and may include a protective buffer around the main feature in the zone.

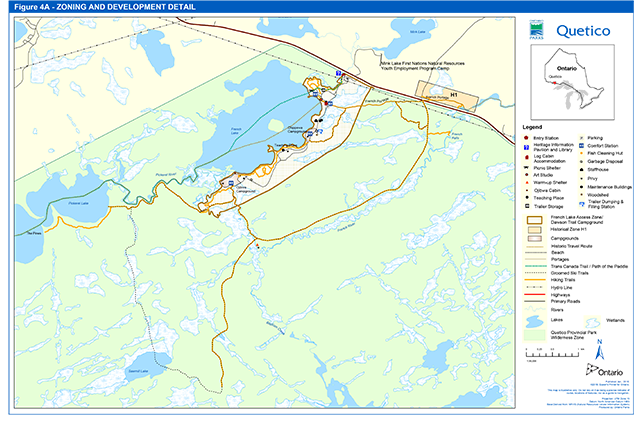

H1 French Portage 36.2 ha

The French Portage runs three kilometres from the mouth of the French River, at the west end of Windigoostigwan Lake to French Lake. The French Portage is part of the historic Kaministiquia River fur trade route used by the French as well as the British. The Northwest Company and the Hudson Bay Company both used this travel route. It was also used by Anishinaabe peoples prior to the arrival of Europeans. In the 1860s it was part of the Dawson Route from what is now Thunder Bay (Fort William) to Winnipeg (Fort Garry). The French portage historic zone is comprised of the parcel of land on the north side of highway 11 that was added to the park in 1968 to encompass the area of a way station on the French portage (Figure 4A). Excavations of the way station site undertaken by Ken Dawson of Lakehead University yielded a 1871 five cent piece, square nails, and a straight boot - (left and right footed boots were introduced in the 1860s) - in addition to many other artifacts (Dawson and Klinefelder 1971).

The eastern landing of the French Portage (at the west end of Windigoostigwan Lake) was painted by Paul Kane in 1846. Paul Kane (1810-1871) was an artist who was one of the first Canadian artist-explorers to record life in the Canadian Northwest before European settlement, over two journeys between 1845 and 1848 (Noftall 2006).

In the summer of 2006, Ken Lister of the Royal Ontario Museum, discovered that one of Paul Kane’s paintings ‘French River Rapids’ had been painted at the east end of the French Portage at Quetico, not at the French River at Georgian Bay on Lake Huron as it had previously been identified. Paul Kane’s own journal makes reference to a sketch at this location and Lister confirmed this by locating the exact site of the painting. This painting portrays an important stage of Ontario’s transportation history and the history of Quetico Provincial Park; the French Portage is a part of this history, as are the historic and prehistoric travel routes that traverse Quetico Provincial Park)

Management intent:

Day-use activities (e.g., hiking and viewing) are permitted in historical zones. Camping is not permitted in historical zones. Development is limited to trails, necessary signs, interpretive, educational, research and management facilities, and historical reconstruction where appropriate.

Interpretive displays recounting the story of Paul Kane’s painting and the fur-trade era use of the French Portage as depicted in the painting will be included in the Education program at the Dawson Trail pavilion.

Ontario Parks and Seine River First Nation will work together to educate park visitors about the relationship of the Lac La Croix/Ojibwa ponies to the First Nations and to the park area, including visits to the Dawson Trail Campground with the ponies and potential use of the French Portage trail in this zone.

Ontario Parks will work with the Ministry of Transportation to ensure that any upgrade or replacement of the highway bridge adjacent to the Kane site will consider design considerations to facilitate safe pedestrian access. A small parking area may be developed to access the French Portage.

Figure 4A Zoning and development detail

Expand Figure 4A Zoning and Development Detail

6.4 Access zones and entry stations

Access zones (A) serve as staging areas, where minimal facilities support the use of other zones such as wilderness zones. Access zones serve to provide access and regulate use to areas of a park geared towards extensive recreation.

Quetico is served by six entry stations (Figure 5). Beaverhouse Lake, French Lake and Nym Lake provide northern entry opportunities and are accessible by road. Cache Bay (Saganaga Lake) and Prairie Portage (Basswood Lake) are located on the southern boundary and are accessible by water only. Lac La Croix entry station was relocated adjacent to the village of Lac La Croix in 1997. Entry stations provide route information, interpretive information, permit issuing services and also serve as an emergency contact.

Five access zones, each with an entry station, were designated in the former plan. All of these zones have been retained (Figure 5).

The French Lake access zone (A1) (230.4 ha) contains the Dawson Trail Campground, staff quarters and offices, the Heritage and Information pavilion and John B. Ridley Research Library, day-use areas, the Teaching Place Roundhouse, and interpretive, hiking and cross country ski trails.

The Cache Bay access zone (A2) (3.1 ha) consists of one small island on Saganaga Lake. The island contains the entry station with staff quarters, the entry station office, and a storage garage, an aircraft landing dock, and a solar powered composting privy for park visitors. Another island was once part of the A2 zone, as it had a cabin for interior crews, which was removed in the early 1990s. This second island has been added to the W zone.

Prairie Portage access zone (A3) (6.1 ha) consists of a peninsula of land adjacent to the Canada - U.S. border between Basswood Lake and Sucker Lake. The entry station has staff quarters, an aircraft landing dock and a hydro-electric powered composting privy for park visitors. The Canada Customs facility ceased operation in 1996 and Ontario Parks has since used the buildings to operate the entry station office, a park’s store and to provide accommodations for entry station staff and interior crews. Upgrades to these facilities occurred from 2006-2008.

Beaverhouse access zone (A4) (8.5 ha) consists of one parcel of land on the shore of a small bay on Beaverhouse Lake. This lakeside parcel contains the entry station facilities which include staff quarters with the entry station office, an aircraft landing dock and a small cabin for interior crews. The Beaverhouse entry station is operated and staffed by Lac La Croix First Nation. There is a historic fire tower adjacent to the access zone. The part of the access zone that was formerly at the end of the access road has been added to the W2 zone.

Lac La Croix access zone (A5) (5.5 ha) is the site of the former entry station. The Lac La Croix entry station was re-located outside of the park near the village of Lac La Croix in 1997, where it is now operated and staffed by members of Lac La Croix First Nation. The A5 site was used by Lac La Croix First Nation for a youth camp and the zoning is being retained to enable future compatible use of the site by the First Nation.

The Stanton Bay forest access road, is located outside of the park boundary north of Pickerel Lake, and provides an alternative entry for Pickerel Lake with a parking lot (also outside of the park) and a boardwalk portage to Stanton Bay. Overnight parking at this location is restricted to Canadian citizens. Due to the fact that the road and parking lot are adjacent to the park boundary access zoning is not required at this location.

Two entry stations are located external to the park.

The Atikokan Area MNRF office, which is located in Atikokan, houses the Quetico Provincial Park headquarters, as well as the Atikokan entry station. Entries through Batchewaung (via Nym Lake) as well as entries through Sue Falls (via Lerome Lake) are processed at this station. Entry to the park via Batchewaung Lake is reached through Nym Lake, located outside of the park. Quetico Provincial Park maintains facilities at Nym Lake which include parking, vault privies and a dock. Parking is available at Lerome Lake for entry into the park via Sue Falls/Cirrus Lake.

A new entry point will not be considered for the eastern boundary of the park due to concerns regarding the availability of resources for construction and maintenance, road use compliance enforcement, visitor dispersal, and uncertainties regarding long term road access (maintenance) via the sustainable forest licence (SFL) holder. The Mack Lake entry location will be changed to Cullen Lake via the portage from Ross Lake. Aircraft will not be permitted to land on Mack Lake but will land instead outside of the park on Ross Lake. Three entries per day are permitted on Mack Lake. The Mack Lake aircraft landing will be removed from regulation.

Additional designation or improvement of access will be contingent upon site selection and visitor use.

Figure 5 Access zones

Management intent:

A major emphasis in the planning and management of Quetico is the development and improvement of opportunities for northern access. The implementation of this basic policy will achieve a number of important objectives. Additional northern entry opportunities will facilitate the use of Quetico by Canadians and, in particular, residents of Ontario. In providing viable alternatives to the traditionally heavily used southern entry points, these entry opportunities will encourage user redistribution within the park. The resulting increase in user activity in areas adjacent to the park’s northern boundary will tend to increase the economic impact of Quetico on the surrounding local Atikokan area.

New development may include staff accommodation and administrative facilities, signs, tertiary roads, overnight camping facilities, and facilities for education, or for research and management. Any development will be subject to the availability of financial and human resources, and carried out in accordance with an approved site or development plan, as well as Class EA-PPCR requirements.

The A5 zone will enable future park access related tourism activity by Lac La Croix First Nation with cultural/ ecotourism, youth facility and or a healing facility. The zone boundary will be adjusted to include the old portage. Cultural trails may be established from the A5 zone to Warrior Hill and to the Painted Rocks.

7.0 Resource stewardship policies

This section presents the detailed site objectives and management actions for Quetico Provincial Park. Implementation of the actions is subject to a number of conditions, including:

- applicable legislation and provincial policy;

- Class EA-PPCR;

- the availability of financial and human resources

- preservation of the cultural values of Anishinaabe people and,

- shared resource decision making with Lac La Croix First Nation

Resource stewardship initiatives may be accomplished through partnerships and sponsorships.

An adaptive management approach will be applied to resource management activities within Quetico Provincial Park. Adaptive management allows for the modification of management strategies in response to monitoring and analysis of the results of past actions and experiences. Adaptive management is a systematic, practical approach to improving resource stewardship.

7.1 Anishinaabe and Métis uses of natural resources

Quetico Provincial Park is located within the boundaries of lands covered by Treaty #3. All members of Treaty #3 have an established claim to inherent rights as set out in Treaties.

Quetico Provincial Park is located in proximity to three Métis Nation of Ontario (MNO) asserted harvesting territories as of 2015. The closest Community Councils that may have an interest include Northwest (Dryden), Kenora, and Sunset Country (Fort Frances/Atikokan).

Quetico Provincial Park overlaps traditional lands and waters of these Anishinaabe and Métis communities. Lac La Croix First Nation, Seine River First Nation, Lac des Mille Lacs First Nation and other Treaty #3 First Nations use the area for hunting, trapping, fishing, wild rice harvesting, medicinal harvesting and ceremonies; and other gathering and travel, and may continue to do so in accordance with section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982. The Anishinaabe spiritual connection to the lands and waters of the park area is a sacrosanct relationship.

Lac La Croix First Nation and Quetico Provincial Park will collaboratively develop a park access plan that assures the community’s preferred means of access including power boat and aircraft access to Anishinaabe resources for spiritual and cultural purposes. Cultural access is at the discretion of the Chief and Council, under advisement from Lac La Croix Elders, and notice to the park superintendent.

7.2 Land management

Land management in Quetico Provincial Park will strive to protect the natural landscape by permitting the forces of nature to function freely, only taking action where necessary to preserve the ecological integrity of the park and the wilderness integrity of its features.

The management of the park’s land base will be directed towards maintaining the natural landscape. Ontario Parks will not dispose of protected area land to individuals or corporations for private use.

If any lands within, nearby or adjacent to the park become available for acquisition; they will be evaluated for purchase with regard to their contribution to park objectives, willing seller/willing buyer and other factors including available funding.

Solid waste will be disposed of outside the park at approved locations.

The Hydro One corridor that runs east west across the northern boundary through the Dawson Trail Campground (in A1) will continue to be administered through a land use permit (LUP).

Ontario Parks will pursue the designation of Dark-Sky Preserve by the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada to enhance the protection of the quality of the night sky over Quetico Park by minimizing light pollution. A Dark-Sky Preserve is an area in which no artificial lighting is visible and active measures are in place to educate and promote the reduction of light pollution to the public and nearby municipalities.

7.2.1 Industrial/commercial uses

The following uses are not permitted within the Quetico Provincial Park boundary:

- Commercial forestry.

- Prospecting, staking mining claims, advanced exploration, working mines.

- Extraction of sand, gravel, topsoil or peat.

- Commercial electricity generation.

- Other industrial uses.

7.3 Commercial tourism services

Ontario Parks will continue to support the existing tourism-based economic activity which benefits the Lac La Croix First Nation and the Town of Atikokan and surrounding area. The provision of guiding and outfitting services from bases outside Quetico Provincial Park will be encouraged, consistent with the park goal and objectives.

The establishment and use of commercial outpost camps within the park is prohibited.

Ontario Parks and Lac La Croix First Nation will practice shared resource decision making when exploring cultural and ecotourism opportunities associated with A5 (Lac La Croix access zone) and the current Lac La Croix Entry station.

7.4 Adjacent land management

Lands designated as General Use Area

Surrounding land uses include commercial trapping, commercial bait harvesting, commercial forest operations, commercial tourism, mineral exploration, and hydro-electric power generation. In the area adjacent to the eastern boundary of the park, mining claims continue to be staked and mineral exploration and development is ongoing. Exploration is focusing on gold deposits as well as volcanogenic massive sulphide deposits of copper and zinc. The revised terms of reference for an individual environmental assessment for the Hammond Reef Gold project were released in January 2012, and permitting is underway

There are active proposals for mines on public lands in the Superior National Forest adjacent to the BWCAW in Minnesota. One of these is the high profile Twin Metals proposal for an underground mine for the extraction of copper, nickel and other metals near Ely, in the Rainy River watershed that flows north and west into the BWCAW, and then out of Minnesota into Quetico and Rainy Lake.

Ontario Power Generation’s Atikokan Generating Station is located approximately 20 km to the north of the park near the Town of Atikokan. It originally consisted of one coal-fuelled generating unit that produced up to 211 megawatts (MW) and was recently converted to wood fibre biomass (pellet fuel).

A small part of Quetico Provincial Park in the Batchewaung Lake area abuts the municipal boundaries of the Township of Atikokan. The Official Plan for the Township identifies the watershed of Quetico Provincial Park as an area of resource management and land use activities where the protection of park values should be considered. The values of Quetico Provincial Park within the Township of Atikokan include critical landform vegetation types, wilderness zone (mechanized travel not permitted in this area), Trans Canada trail (non-mechanized travel only) and an entry point to the park (Batchewaung Lake via Nym Lake). Development proposals will be reviewed by MNRF and Ontario Parks staff to determine impacts on the park and possible mitigation/minimization methods.

The development of 4 hydroelectric projects on the Namakan River was initiated several years ago. The project design was subject to a proponent-led EA process and Ontario Parks was part of the agency review. Concerns with the proposal, which included upstream impacts to Quetico Provincial Park water levels and the environmental assessment process itself, were identified and the EA was suspended in the fall of 2011. In 2012, the EA process was re-initiated for one of the original hydroelectric projects at High Falls with a new design intended to prevent impacts to Quetico Provincial Park water levels. The project was cancelled in 2013, and there has been no recent activity associated with hydroelectric development on the Namakan River. Ontario Parks will participate in the agency review of the EA process for any future hydroelectric proposal.

When Ontario Parks staff review development proposals on adjacent land, impacts of the proposal on ecological integrity, water quality, the experience of remoteness, noise levels, viewscapes, travel routes and wilderness integrity will be considered. Ontario Parks will discuss development proposals with Lac La Croix First Nation to ensure that both park values are protected and that Anishinaabe cultural values are protected.

Quetico Provincial Park forms part of the Rainy Lake watershed and lies north of the international boundary waters between Canada and the U.S. (Figure 1). The Canadian waters were designated by the Canadian and Ontario governments as part of the Boundary Waters-Voyageur Waterway, a Canadian Heritage River, in 1996. The southern boundary of the park is contiguous with the BWCAW within the Superior National Forest, while Voyageurs National Park abuts the international boundary to the west of Quetico. This 1,000,000 hectare suite of protected areas surrounds the historical travel corridor along the boundary waters between Lake Superior and Lake of the Woods, and has many historical, natural heritage, and recreational interpretive themes in common with Quetico.

7.5 Vegetation management

Management of vegetation within the park will be directed towards the maintenance of an evolving natural succession of communities, and natural disturbances (fire, blowdown). The Quetico Provincial Park Fire Management Plan is used to accomplish vegetation management objectives such as renewal of pine stands.