Appendices

Appendix 1: Key Terms

This section includes key terms and terminology used for the purposes of this document. Alternative terminology and phrases with similar descriptions may be used in different contexts and settings.

Ableism – Discrimination towards someone based on their abilities, often favouring those who do not have a disability and seeing less value in those that do. This includes discrimination directed towards people with physical disabilities, people with mental health conditions or cognitive impairments (sanism), people who are D/deaf or hard of hearing (audism), or people who are blind or visually impaired, among others. Ableism can be reflected in actions, words, behaviours, and access issues.

Anti-Black racism – Prejudice, attitudes, beliefs, stereotyping and discrimination that is directed at people of African descent and is rooted in their unique history and experience of enslavement. Refers also to the policies and practices rooted in Canadian institutions such as education, health care and justice that mirror and reinforce beliefs, attituces, prejudice, stereotyping and/or discrimination towards people of African descent.

Anti-Indigenous racism – Ongoing race-based discrimination, negative stereotyping, and injustice experienced by Indigenous Peoples within Canada, including First Nations (status and non-status), Métis, and Inuit people. It includes ideas and practices that establish, maintain, and perpetuate power imbalances, systemic barriers, and inequitable outcomes that stem from the legacy of colonial policies and practices in Canada.

Anti-oppression – Oppression is the use of power or privilege by a socially, politically, economically, culturally dominant group (or groups) to disempower (take away or reduce power), marginalize, silence, or otherwise subordinate one social group or category. Anti-oppression requires people to acknowledge the ways in which oppressive systems show up in thinking, action, and practices, and to actively dismantle this oppression as it appears.

Anti-racism – A process, a systematic method of analysis, and a proactive course of action rooted in the recognition of the existence of racism, including systemic racism, that actively seeks to identify, remove, prevent, and mitigate racially inequitable outcomes and power imbalances between groups and change the structures that sustain inequities.

Antisemitism – A perception of Jewish people that is often expressed as hatred towards Jews.

Child/children – May include children and/or youth. In some contexts, children and youth may be referred to as “students in publicly funded schools.”

Children’s Treatment Centres (CTCs) – Provide multidisciplinary assessment and rehabilitation services (physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and speech-language therapy) to children and youth with physical disabilities, developmental disabilities, or communication disorders. CTCs are accountable for all SmartStart Hubs functions.

Children with special needs – Broad term used to refer to children and youth with identified service needs, which includes children with disabilities as well as children who may not identify as disabled.

Culturally safer services – Service provision that acknowledges the power dynamics that exist between a provider and the person receiving the service and works to dismantle this imbalance. Cultural safety recognizes that providers may not know the norms and customs of every culture they may encounter, and instead asks providers to provide an environment that is free of racism, discrimination, and oppression. Culturally safer service provision relies on respectful engagement by the provider, to support all children, youth, and families to feel safe receiving services.

Early identification and intervention – The prompt identification and, by implication, intervention to address early health, developmental, and/or behavioural issues which may impede healthy growth and development. Early identification is key for early intervention and for achieving optimal child, parental, and family health.

- Earliest age in development – The early years from birth to school start are a critical window during which to foster nurturing and responsive caregiving capacity and safe and stimulating environments and experiences that are key to healthy brain development and monitor children’s development to detect difficulties as early as possible.

- Earliest intervention opportunity – Following identification of a difficulty or need, ensure that children and youth are supported as early as possible to mitigate the need for more intensive services later in life.

Early years and childcare service providers – May include childcare staff, Registered Early Childhood Educators, resource teachers, administrators and other individuals working in early years and childcare settings.

Educators/Education Workers – May include classroom teachers, early childhood educators, special education resource teachers, learning resource teachers, literacy or numeracy coaches, and educational assistants. Educators and education workers with the school team including administrators (such as principals and vice-principals) and school-based professionals (including SLPs, psychologists, ABA therapists, etc.).

Equitable service – Service that is just, unbiased, and reasonable, and provided in a way that gives everyone a fair opportunity to reach their fullest potential.

Equity-deserving or marginalized groups – Those groups and communities that experience discrimination and exclusion (social, political and economic) because of unequal power relationships across economic, political, social and cultural dimensions.

Families – Includes all family members or caregivers who are regularly involved in a child’s life and care (e.g., parents, siblings, grandparents, extended family, foster parents, legal guardians).

Home programming – A specific, individualized program, implemented by the parent or person providing care in a child’s home.

Intersectionality – Acknowledges the ways in which people’s lives are shaped by their multiple and overlapping identities and social locations, which, together, can produce a unique and distinct experience for that individual or group, for example, creating additional barriers or opportunities.

Islamophobia – A prejudice towards, and hatred of, Muslim peoples that can lead to hate, threats and abuse of Muslim people, or those assumed to be Muslim. Islamophobia is entrenched in many systems and institutions.

HCD-ISCIS – The Healthy Child Development Integrated Services for Children Information System (HCD-ISCIS) provincial data system used for collecting information about the PSL Program.

Lead Agency – The entity that enters a Transfer Payment Agreement with MCCSS to deliver the PSL program and may contract other agencies to deliver services.

Parents – Used throughout this document to refer to parent(s), caregiver(s), and/or guardian(s).

Preschool – Refers to the period from when a child is born to school start.

Primary Care – The first level of medical care provided by general practitioners and family physicians, nurse practitioners, nurses, and other allied health professionals. The goal of primary care is to monitor, assess, and treat the healthcare needs of patients.

Racialized – Recognizing that race is a social construct, we can describe people as a “racialized person” or “racialized group” instead of the more outdated and inaccurate terms “racial minority”, “visible minority”, “person of colour” or “non-White”.

Rehabilitation services – Includes speech-language pathology, occupational therapy, and physiotherapy provided by and/or supervised by speech-language pathologists (SLPs), occupational therapists (OTs), and physiotherapists (PTs).

Rehabilitation service providers – Includes regulated SLPs, OTs, and PTs providing speech and language therapy, occupational therapy and physiotherapy services and include, where appropriate, supportive staff such as Communication Disorder Assistants (CDAs) as well as Therapy Assistants (TAs).

School start – A child may begin school at age 4 or 5 in kindergarten. When a child turns six years old, they must attend school (Grade 1) in September of that year.

Service providers – Refers to agencies delivering the Preschool Speech and Language Program (i.e., PSL Lead Agencies and their partners) and/or agencies delivering Children’s Rehabilitation Services program delivered through CTCs and their partners. In cases where statements apply to a specific provider, this will be indicated as “service provider individual” or “individual service provider”.

Solution-focused – Provides a humanistic approach to service provision by recognizing the child/youth (and their family) as the expert,

Strengths-based – Moves beyond a deficit lens to recognize the resilience, strengths and capabilities of a child/youth and their family. This approach builds upon these attributes to empower the child/youth and their family.

Systemic oppression – The intentional disadvantaging of groups of people based on one or more of their identities while advantaging members of the dominant group (gender, race, class, sexual orientation, language, etc.); is systematic and has historical antecedents.

2SLGBTQQIA+ – 2-Spirit (Two-Spirit), lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, questioning, intersex, asexual. The + denotes the diversity of remaing identities not covered in the acronym.

Two-Spirit – A contemporary pan-Indigenous term used by some Indigenous 2SLGBTQQIA+ people that honours male/female, and other gendered or non-gendered spirits, as well as spiritual and cultural expressions. The term may also be used interchangeably to express one’s sexuality, gender, and spirituality as separate terms for each or together as an interrelated identity that captures the wholeness of their gender and sexuality with their spirituality.

Trauma-informed – Trauma-informed care seeks to recognize that children and families are impacted by a variety of experiences and situations – both past and present – which may affect their health or ability to seek care. Trauma-informed care acknowledges that trauma is prevalent and seeks to integrate knowledge about trauma into all practices, and to actively avoid re-traumatization.

Xenophobia – A fear or hatred of strangers or foreigners, including immigrants and migrants, or those who are perceived to have migrated.

Appendix 2: Cultural Change Leadership

Requirements identified in the following section, as outlined within the SmartStart Hubs Policy and Practice Guidelines, are expected to extend to PSL Lead Agencies and CTCs to share the responsibility of cultural change leadership for continual system improvement.

Service providers are expected to be leaders and drivers of change, both within the organization and with service partners, toward a service culture that is:

- strengths-based and solution-focused,

- child- and family-centred,

- trauma-informed,

and that promotes:

- equity,

- anti-oppression,

- anti-ableism, and

- anti-racism, including dismantling anti-Black and anti-Indigenous racism.

footnote 59

Environmental, social, and attitudinal barriers can result in challenges accessing supports for many people, particularly for those from marginalized groups, including people with disabilities, Black, Indigenous, and racialized people, women, 2SLGBTQQIA+ people, people from non-Western/non-Christian religions/cultures, low-income people, and people experiencing intersectional oppression.

For many families, traditional models of service delivery, including some professional behaviours, can be experienced as patronizing and invalidating of their lived experiences, expertise, and priorities, and can feel unwelcoming or unsafe.

These experiences are even more common for families who are racialized or from equity-deserving (marginalized) groups, and can be compounded by inherent bias, sexism, racism, ableism, xenophobia, Islamophobia, antisemitism, or anti-Blackness, and other modes of systemic oppression.

Families that have negative experiences interacting with the service system or with service providers may experience a lack of trust and engagement in the service system. This may negatively impact families’ access to, and participation in services, which can impact the effectiveness of those services.

Examples of families’ experiences of bias/discrimination/patronizing interactions with care providers from the health and social sectors include:

- Using technical language or jargon without explaining in plain language.

- Discounting the lived experiences and expertise of family members (intentional or unintentional).

- Feeling rushed through appointments or visits with clinicians.

- Feeling that families with more privilege get access to more services more quickly than others.

- Culturally insensitive questions that exhibit bias.

- Failure to recognize the variety of meanings and connotations that different words or phrases have in different cultures (e.g., in some Indigenous communities, parents would not say they have a “concern” about their child; certain East Asian cultures may associate the word “play” with a negative connotation).

- Feeling judged or blamed for an inability to implement suggested home practice (due to social determinants or systemic barriers providers may not be aware of) and worrying about being reported to child welfare services.

- Feeling certain diagnoses (e.g., Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder) are more likely to be suspected for certain populations based on stereotypes.

PSL Lead Agencies and CTCs will continuously work towards providing culturally safer services for families of all races and cultures and will ensure that all people feel safe when receiving services and supports. Cultural safety is an outcome based on respectful engagement that recognizes and strives to address power imbalances inherent in systems.

It is important for service provider organizations and individuals as part of the service system to adopt a curious and humble perspective when working with families. Just as family-centred service asserts that families are the authority on their children, cultural humility acknowledges oneself as a learner when it comes to understanding another’s experience. Cultural humility is a process of self-reflection to understand personal and systemic biases and to develop and maintain respectful processes and relationships based on mutual trust.

Service providers will provide services that are trauma-informed, meaning that service provider staff will be aware of the impact of trauma and endeavour to make people feel safe in their interactions.

Service providers will work to address concerns related to discrimination and bias and will evolve their approach over time to earn the trust of those they serve.

Requirements for PSL Lead Agencies and CTCs:

Lasting cultural change requires a multi-pronged approach supported through formal and informal levers, including policies, processes, tools, training, performance measures/metrics, change agents, and communities of practice.

Service providers are required to put in place the following elements, towards continuous improvement in the provision of culturally safer services:

1. Training

PSL Lead Agencies and CTCs will provide training for all staff providing services on:

- Anti-racism, including examination of race-based discrimination and biases.

- Training can be general, as well as specific to the workplace setting to ensure that Black, Indigenous, and racialized families and families from diverse backgrounds, cultures, and lived experiences have interactions with the service system that are free from racism, prejudice, and discrimination.

- Training can highlight topics such as recognizing racial microaggressions (either intended or unintended) that may have a negative impact on racialized children, youth, and families or provide experiential learning to increase staff awareness of families’ daily realities, their intersectional identities, and the systemic barriers they may face.

- Consider partnering with culturally relevant agencies to deliver these trainings.

- Indigenous cultural competency

- Service providers will work with local Indigenous communities to offer training/learning experiences about cultural safety.These experiences may include opportunities for general learning about the history of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples in Canada as well as impacts and intergenerational effects of colonial policies and practices, such as residential schools, as well as training and learning opportunities to deepen knowledge of the specific Indigenous communities that they serve.

- Strengths-based and family-centred service training on the F-words for Child Development. Training on family-centred service delivery is also encouraged.

- Solution-focused coaching.

- Trauma-informed service delivery approaches.

2. Engagement with Indigenous Communities

Service providers will work with Indigenous communities to provide a culturally safer, trauma-informed, and responsive service experience for First Nations, Métis, Inuit, and urban Indigenous children and youth and families in Ontario.

This includes working together to examine and improve program components and processes so that when a family self-identifies, they can access culturally safe and responsive care. For example, collaborations with local Indigenous communities may support delivery of family-based supports that are specifically for families whose children have a developmental concern and are Indigenous. Such supports should also consider possible intersectional identities.

All work that is requested of Indigenous communities/orgnaizations should include discussions about compensation. Relationship building must respect, and be responsive to, Indigenous rights and be grounded in the Ontario Indigenous Child and Youth Strategy and the Urban Indigenous Action Plan.

This section aligns with expectations for developing relationships with Indigenous service providers to improve service delivery practices and processes for Indigenous children and families, as outlined on page 22 and 40 of the SmartStart Hubs Policy and Practice Guidelines.

3. Engagement with a diverse range of families

It is important for service providers to engage with families to understand their service experiences and obtain advice and input on service delivery approaches.

Service providers will develop and implement child and family engagement mechanisms at the organizational level to enable children, youth, and families to provide ongoing guidance and advice regarding service planning and delivery. Service providers may leverage existing mechanisms to embed the voices and families with lived experience into all aspects of service provision.

It is important that efforts are made to ensure that such family engagement mechanisms reflect the diversity of the community. For many racialized and other equity-deserving groups, formal tables and committees have historically not always been welcoming, safe, or inclusive for everyone. Service providers will work to seek input from the diverse communities they serve, using creative and flexible approaches that reduce barriers for people, such as partnering with existing, trusted community groups to initiate engagement, creating opportunities to provide anonymous feedback in written or oral formats and multiple languages, scheduling meetings on evenings/weekends and in convenient locations (e.g., EarlyON Child and Family Centre), hosting virtual meetings, or hosting focus groups without clinical staff involvement (for example, led by members of these communities or past program participants) to increase safety.

Service providers are encouraged to consider approaches to compensate families for their time, reduce barriers related to childcare or transportation, and establish paid positions, such as family engagement workers, if possible. Service providers are also encouraged to partner with other service providers (e.g., other MCCSS-funded providers) in their communities to share learnings and leverage knowledge to minimize the burden on equity-deserving groups.

4. Incorporate diversity, equity, and anti-racism into organizational policies

Service providers will formally incorporate the principles of diversity, equity, anti-oppression, anti-ableism, and anti-racism, including dismantling anti-Black and anti-Indigenous racism, into their organizational policies, including adopting diverse hiring practices and embedding approaches to equity and anti-racism in their service delivery, encouraging engagement with local cultural service organizations, and setting key performance indicators related to these practices.

Appendix 3: The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) framework and F-words for Child Development in Practice

International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF)

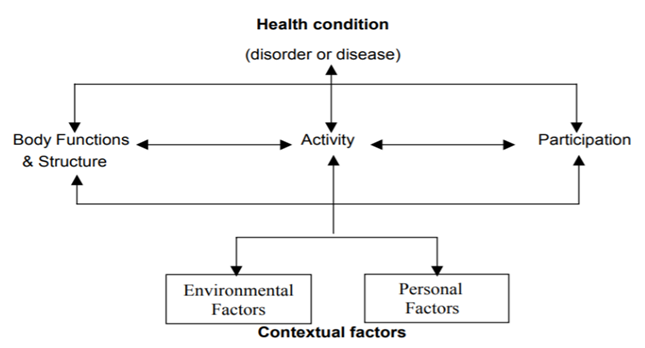

The World Health Organization’s ICF framework provides a useful way of conceptualizing the child and their communication/developmental difficulties holistically and in the context of their everyday lives (see Figure 7). The ICF framework considers children’s impairments in body structures and functions, their activity limitations, and their participation restrictions, while also recognizing the impact environmental and personal factors can have on children’s health.

The ICF framework should be considered in assessment, goal setting, and intervention planning to support consideration of all components and how each may be impacting the child’s development, both within and outside of the clinic.

Figure 7: The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF)

The F-words for Child Development

The F-words for Child Development (Function, Family, Fitness, Fun, Friends and Future) were developed at CanChild Centre for Childhood Disability Research in 2011 to help clinicians and families conceptualize child development within the ICF framework.

The F-words in Practice

Family-Centred Planning and Goal Setting

Many service providers are using the F-words with families to change the conversation in a way that encourages families to celebrate their child’s unique skills, personality, and interests. Just as the ICF components are applied in assessment, goal setting, and intervention, so too can the family-friendly F-words be used to support planning and delivery of these program elements.

For example:

- A goal within the Function domain for children with communication needs could include following meaningful directions with visual and verbal supports.

- A goal within the Friends and Fitness domain may support children to take-turns and participate in active play with peers.

- When considering Family, the family pet’s name could be included as a meaningful target word.

Collaboration with other Service Providers

The F-words can be applied across programs within health, educational, recreational, and vocational services to promote child and youth development and family wellbeing. They can facilitate development of common templates, cross-program collaborations, and transitions that take a holistic perspective in serving families and meeting family-centred goals.

For example, using the F-words as part of child- and family-centred, strength-based conversations with other partners in the broader children’s services system (e.g., Registered Early Childhood Cducators, Infant and Child Development Program workers, educators) builds a common language so that everyone is collaborating in the best interest of the child and family.

For more ideas, tools and resources, visit the CanChild Knowledge Hub at www.canchild.ca/f-words.

Table 1: Using the ICF and F-words for Child Development to support assessment and goal setting

| ICF component | Description | Assessment | Example Treatment Goal* | Why is the goal meaningful to the child and family? | Associated F-word(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body Structures and Body Functions | Anatomy and physiology of the body. | Evaluation of jaw structure and dentition; completing an articulation test. | Increase production of /s/. | Improve speech clarity to help friends and family understand the child’s message. | FAMILY, FRIENDS |

| Activities | Ability to perform a task or action. | Ability to use visual supports to support communicative function. | Use low tech device to make requests and choices. | Develop requesting skills to improve independence and overall communicative function. | FUNCTION |

| Activities | Ability to perform a task or action. | Assess current mobility device and supports. | Increase core strength and flexibility so that child can used an adapted support device. | Allow child to play soccer with older sibling. | FAMILY, FUN |

| Participation | Involvement in life situations. | Use of communication in ‘conversation’ and play with peers. | Increase turn-taking during play with peers. | Improve turn-taking skills to support meaningful peer interactions and relationships. | FUN, FRIENDS |

| Participation | Involvement in life situations | Assessment of adaptive equipment and clothing. | Increase exercise tolerance (1 hour hiking). | Active family wants to continue favourite activities (hiking) together. | FAMILY, FUN |

| Environmental Factors | Physical, social, attitudinal environments | Understand the child’s learning environments (e.g., attending childcare, family engagement and interaction style). | Build parent capacity through training and coaching. | Develop parent capacity so that parents feel empowered and have new skills to support their child’s development. | FAMILY |

| Personal Factors | Characteristics of the individual (child) | Assess interests, attention, behaviours, motivation; consider age. | Improve attention or self-regulation skills during soccer. | Improve attention and self-regulation to help the child successfully engage in a favourite activity. | FUN, FITNESS |

* S.M.A.R.T. goals should be developed based on example treatment goals identified: S= specific, M = measurable, A = attainable; R = realistic/relevant (meaningful); T = time-based (e.g., X will attend to 5 min of soccer instructions with minimal support by the end of the season).

Appendix 4: Wait Management Evidence-Informed Strategies

There is no one way to address wait times and service providers are continually making operational decisions and implementing innovative approaches to use their resources more efficiently, manage service pressures, and reduce wait times at various points in the service delivery model or through the service system. Service providers have much to learn from each other and are encouraged to seek out innovations from other partners within and across sectors and to share their own successes in wait management so that efficiencies that have been realized are translated and/or adapted in other communities.

Families who are waiting for services can be supported through various strategies focused on increasing access, improving service experiences, and improving functional outcomes for children and youth.

The following describes some practices outlined in the guidelines that can help manage waiting experiences:

| Increasing Access | Improving Family Experience | Enhancing Functional Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

Early universal supports and connections to timely services means needs are addressed sooner and more appropriately. This reduces the number of children on waitlists and the wait times for those who continue to wait. | Earlier and regular engagement sets clear expectations, helps families build skills to foster development at home, reduces anxiety, and strengthens relationships with service providers in preparation for additional service. | Early identification and intervention results in better functional outcomes, especially at critical stages of development, and prevents the need for more intensive services later in life. |

Evidence-informed Strategies

There is much to learn from the research evidence and from practice in Ontario and other jurisdictions. Some strategies for improving the wait experience, adapted from current practice and various evidence-informed models and sources,

Selection of Strategies for Managing Wait Experiences

Table 2: Strategies for managing wait experiences

| Strategy | Description |

|---|---|

| Seek Consent Early and Optimize Intake |

|

| Provide Information and Skill Building Supports |

|

| Coordinate Prioritization and Triage |

|

| Implement Tiered Services |

|

| Hold Clinics to Build Family Skills |

|

| Stay in Touch |

|

| Maintain Equity |

|

| Implement Staffing Efficiencies |

|

| Measure Progress and Set Targets |

|

Appendix 5: Tiered Services and Case Examples

Tier 1/Universal Resources and Supports for Families in the Service Pathway

Resources may include fact sheets, milestone charts, videos, e-learning modules, or webinars where the focus of the learning is on the family such as:

- An e-learning module on communication may show parents how to use strategies (e.g., gestures, waiting, repeating) to support communication during everyday routines and activities such as playing, reading, singing.

- A fact sheet available online may share parenting tips and tricks to support early literacy, speech sound or vocabulary development, toileting, printing, or sensory sensitivities that may include making changes to a child’s routine and/or environment.

- A online resource with milestones for motor development may raise caregivers’ awareness about the ages at which they can start encouraging certain motor skills (e.g., stair climbing, holding a utensil, jumping) or raising concerns if skills are not developed.

The table below lists some of the high quality MCCSS-funded resources for families to access information before or after intake. These can also be used to increase awareness and knowledge among community, health, and education partners.

Table 3: Tier 1/Universal Resources for Families and Community Partners

| Resource | Website Address |

|---|---|

| Partners for Planning (P4P) | Resources for Planning: Resources and tools for families that aim to empower them to plan for and create a full life and secure future (e.g., Early-Years Toolkit, Planning Tip Sheets, Introduction to Registered Disabilities Savings Plan). |

| F-words for Child Development | Training: https://www.canchild.ca/en/research-in-practice/f-words-in-childhood-disability/f-words-training CanChild has developed self-paced, online training to help parents and service providers learn about the F-words for Child Development and explore ways in which they can be used. The content includes:

The training is available free of charge, and participants receive a certificate following completion of the program to confirm their participation. The aim of this training is to provide parents and service providers information that will help them work together to develop a vision for services and identify individualized goals that are meaningful to the child and family. Tools and Resources are available through the Knowledge Hub: https://www.canchild.ca/en/research-in-practice/f-words-in-childhood-disability |

| Resource | Website Address |

|---|---|

| Enhanced 18-Month Well-Baby Visit | Enhanced 18-Month Well-Baby Visit | ontario.ca |

| Early Years Check-In | Parent Tool and Resources to foster/monitor development: https://eyci.healthhq.ca/en Professional Portal: https://eyci.healthhq.ca/en/professionals |

| Play & Learn Activities | Website with 80+ activities for parents/caregivers to foster development at home: https://playandlearn.healthhq.ca/en Activity Discovery Subscription Service: https://playandlearn.healthhq.ca/en/activity-discovery |

PSL Interventions Classified by Tier 2 or Tier 3

The table below provides general guidance for conceptualizing PSL interventions by Tier 2 and Tier 3. See PSL HCD-ISCIS Data Tracking Manual for intervention definitions.

Table 4: PSL Interventions Classified by Tier 2 and Tier 3

| Tiers by PSL Intervention Type |

|---|

TIER 2 – additional supports beyond Tier 1/Universal intervention necessary for some

|

TIER 3 – individualized, specialized intervention beyond Tier 2 essential for a few Individual Treatment-SLP (IT) Individual Treatment-Mediator (IM) |

PSL Clinical Case Examples

Example #1: Language Needs

A 19-month-old child is referred to the PSL program by their parent due to concerns that their child is not using many words. For Tier 1/Universal Intervention, the parents are provided digital resources by email shortly after intake (e.g., communication milestones, language-facilitation activities). Before booking the initial assessment, the parents will identify whether further services are required. The child will be scheduled for an initial assessment if ongoing concerns are identified or will be removed from the waitlist if no further needs exist (discharge).

Example #2: Speech and Language Needs

A family refers their 21-month-old child due to concerns about their small vocabulary. For Tier 1/Universal Intervention, general information was provided to the family at intake. At the time of booking the initial assessment, the family confirms they would like to proceed with the initial assessment because their child has made limited progress. At initial assessment, their 24-month-old child presents with speech and language difficulties characterized by limited consonant inventory and vocabulary. In consultation with the family, Tier 2 parent training is offered (e.g., Target Word, parent coaching) and the family attends regularly. Depending on the child’s response to the Tier 2 intervention and in discussion with the family, next steps may include: (a) discharge if no further needs are identified, (b) access to another Tier 2 intervention (e.g., group therapy or home program) if some additional needs are identified, or (c) move to Tier 3 if needs identified require more specialized, intensive intervention (e.g., the child is found to have a significant motor speech disorder). In the case of identified motor speech difficulties, intervention should be aligned with the Motor Speech pathway.

Example #3: Language and Social Communication Needs

A family refers their 3 year and 5-month-old child. Through the intake process, the family identifies communication and motor concerns. With consent, the family is connected to the local SmartStart Hub to explore their developmental concerns. For Tier 1/Universal Intervention, the family also receives general resources at intake. At the time of booking the initial assessment, the family confirms they would like to proceed with the initial assessment because significant needs are still present. At the initial assessment, the child is 3 years, 8 months and presents with severe receptive, expressive, and social communication difficulties. The child also has difficulty with self-regulation. This child may require individualized, specialized services at Tier 3 (e.g., 1-1 visits to implement augmentative supports) as a first intervention, based on their age and significant communication and self-regulation needs as well as connections to other programs and services if connections have not already happened through the SmartStart Hubs (e.g., ASD Diagnostic Hub, Infant & Child Development Program). Given the complexity of concerns, a multi-disciplinary initial assessment may be planned in some regions, depending on local agreements and locally developed clinical service pathways. Services across disciplines and programs should be coordinated and integrated to best support this child and family through their service journey.

Rehabilitation Clinical Case Examples

Example #1: Occupational Therapy – Handwriting Concerns

An occupational therapist in a grade 2 classroom observes three children with different handwriting challenges. The OT works with the teacher to incorporate strategies (e.g., modelling writing posture, improving paper position and stability and experimenting with different pencil grasps) with the entire class as a Tier 1 intervention.

Example #2: Speech-Language Pathology – Articulation

In a grade 1 classroom, the teacher and SLP jointly identify some children with mild articulation problems. As a Tier 1 intervention, the SLP supports the teacher to plan games for the whole class that are fun and engaging and rely on correctly pronouncing target sounds and words to improve the children’s articulation skills.

Example #3: Occupational Therapy – Self-Regulation

A grade 5 teacher asks the school-based OT to provide some strategies for students who have trouble regulating their emotions and behaviors. After consulting with the teacher, the OT recommends the following Tier 1 interventions to incorporate into the classroom routine to promote students’ self-regulation:

- Practicing deep breathing exercises.

- Leading guided visualizations as students relax with eyes closed.

- Incorporating quick movement breaks into the classroom routine.

One student is identified for further support and the OT works with the teacher and the OTA to incorporate Tier 2 supports. Adults at the school, including the teacher and other staff, are taught to use specific positive behavioural support strategies with this student.

Example #4: Occupational Therapy – Developmental Milestones

A family approaches their local SmartStart Hub expressing concern that their 4 year old is not meeting developmental milestones for self-care skills (i.e., toileting). After connecting with the SmartStart Hub, the family is provided with web-based resources (e.g., Caring for Kids website) to support their child at home while waiting for an assessment. Based on the results of a clinical assessment, the family is referred to a group program as a Tier 2 support. Following the six-week play group, the child is identified as needing additional support and is placed on the waitlist for Tier 3 rehabilitation services (1-1 interventions).

Appendix 6: PSL Program Outcome Measurement and Monitoring

Outcome measurement and monitoring can be used to capture change over time, assess response to intervention,

For children without permanent hearing loss, the focus of outcome measurement is on communicative function and participation. Although communicative function and participation are as important for children with permanent hearing loss, spoken

Outcome Measurement Tools for Children Without Permanent Hearing Loss

Children with speech, language, and communication needs (who do not also have permanent hearing loss) must be assessed at regular, clinically meaningful intervals using the Focus on the Outcomes of Communication Under Six (FOCUS-34)

Monitoring tools for children with permanent hearing loss

Spoken Language

Spoken language outcome monitoring for children with permanent hearing loss must be conducted using the Preschool Language Scales, 5th ed. (PSL-5)

For these children, Speech-Language Pathologists should administer the MBCDI-2 (up to 18 months) or the PSL-5 (19 months and older) every 6 months until the child is 3 years old, and annually thereafter until school start (Figure 8). This measurement schedule is recommended regardless of whether children score within normal limits on either test as children in this population remain at risk and require ongoing monitoring.

Figure 8: Measurement schedule for the MBCDI-2 and PSL-5

Signed Language

Signed language outcome monitoring for children with permanent hearing loss is conducted as part to the Infant Hearing Program. The Visual Communication and Sign Language Checklist

PSL Program Clinical Tools and Guidance: Next Steps

In addition to the current PSL measurement and monitoring tools, the development of other PSL clinical tools and guidance is in progress to further enhance clinical decision making by SLPs at the individual and program-levels.

Profile of Preschool Communication (PPC)

Along with measuring outcomes using valid and reliable tools, it is important to gather information about factors that are known to be associated with children’s communication outcomes to provide a more detailed description of the child and the population served. Over time, this information could be used clinically as well as for program planning and delivery, such as developing clinical service pathways and determining resource allocation.

To support collection of information, the ministry is preparing to introduce the Profile of Preschool Communication (PPC),

Individual Vulnerability Testing (IVT)

Children with permanent hearing loss developing spoken language are at increased risk for delays in specific areas of speech and language including vocalization, articulation, vocabulary, grammar, and early literacy, even when they score within age expectations on program-level language monitoring tools (i.e., MBCDI-2 and PSL-5 in the PSL program).

Ministry resources are being developed to support individual vulnerability testing (IVT) for this group of children. A set of standardized tests have been identified, and should be administered to inform clinical practice, based on SLP clinical judgement. Pilot studies implemented by some PSL Programs in 2018-2020 found recommended IVT to be challenging to complete with some children. As a result, only program-level spoken language outcome monitoring is mandatory (i.e., the MBCDI-2/PSL-5).

Appendix 7: Elements of Intervention Intensity and Evidence to Support Clinical Decision-Making

Intervention intensity is determined by multiple factors and decisions should be informed by best available research evidence for populations, child and family factors,

While monitoring the child’s progress towards success criteria for a meaningful goal, intervention intensity should be at a high enough level to realize benefits while recognizing that more intervention is not always better. Intervention should be changed, paused, or ended when success criteria are met or progress has plateaued.

Table 5: Elements within Intervention Intensity

| Element | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Dose | The number of teaching episodes within one intervention session that is directly linked to the child’s goal. | 60 trials per session |

| Dose form | The task activity in which the teaching episodes are delivered. | play, snack time, shared book reading |

| Dose frequency | Number of times the intervention is provided per week or month. | 1 session per week |

| Intervention frequency | Time over which a specified intervention is provided. | 8 weeks |

| Cumulative intervention | The product of: dose X dose frequency X intervention frequency | 60 trials/session X 1 session/week X 8 weeks = 480 trials |

Intervention intensity can be achieved or increased when coordinated and integrated with other programs and home-based services such as the Infant and Child Development Program. For example, a home-visiting provider could support the parents to incorporate trials or strategies into daily interactions. Regular communication between service providers is strongly encouraged to collaborate on goals and support implementation along with the family.

Though not exhaustive, the following evidence should be considered when making clinical decisions regarding intervention intensity. Future versions of the PSL Program Guidelines may expand on this evidence to inform clinical service pathways, as research continues to emerge.

Parent-implemented intervention

Parent-implemented intervention for children with expressive language difficulties/disorders can be effective in supporting children’s communication development when provided at an appropriate level of intensity.

Speech sound disorders (SSD)

- Children with speech sound disorders (SSD) require intensive intervention and more significant SSD needs tend to require greater intervention intensity, (i.e., more trials per session and more sessions),

footnote 89 especially those with apraxia of speech.footnote 90 - A greater number of sessions per week (dosage frequency) over a shorter period of time has been found to lead to faster phonological gains in children with SSD compared to fewer sessions per week over a longer period of time.

footnote 91

Language Disorders

- For children with language difficulties or developmental language disorder (DLD), providing intervention in either more frequent, shorter doses (e.g., 5 min., 2-3 times/week- “little and often”) or less frequent, higher doses (e.g., 20 min., 1 time/week) can both be effective approaches as long as the dosage (number of teaching episodes of the target during the session) is high, especially for morphosyntax.

- A model that is short in duration and high in frequency (e.g., 5 min., 2-3 times/week) lends itself to a parent or educator-mediated model, rather than clinic visits with a service provider.

Appendix 8: HCD-ISCIS and IRSS – Training Overview and Resources

What is HCD-ISCIS?

HCD-ISCIS (Healthy Child Development – Integrated Service for Children Information System) is an internally developed application that supports case management, data collection, and program management for four Healthy Child Development programs:

- Preschool Speech and Language (PSL)

- Healthy Babies Healthy Children (HBHC)

- Infant Hearing (IHP); and

- Blind Low Vision (BLV).

Lead agencies delivering the HBHC, PSL, IHP and/or BLV programs enter demographic and service data, such as assessment and intervention types/dates (recommended, accessed, finished), and outcome measurement tools into HCD-ISCIS. Lead agencies establish their own business processes related to the collection of and entry of data into HCD-ISCIS based on their local circumstances and delivery structures. This may include processes associated with the collection of data from and/or sharing of information with subcontracted partners who are delivering PSL services on behalf of lead agencies.

What is HCD-IRSS?

HCD-ISCIS Reporting Sub-System (HCD-IRSS) is a web-based decision support system that consolidates, transforms, and summarizes the data entered into HCD-ISCIS for the purpose of producing analytical reports to support program management. Within HCD-IRSS there are pre-defined reports currently used by PSL lead agencies, including:

- PSL Annual and Quarterly Reports: These reports provide aggregate service delivery statistics on referrals into the program, assessment, intervention, and wait times.

- PSL Program Activity Report: This report provides aggregate service delivery statistics, specifically reporting performance against the PSL program targets.

- FOCUS-34 Pre-Defined Reports: These reports provide aggregate statistics on the use of the FOCUS-34 outcome measurement tool in PSL, including information about visits, scores, and associated recommendations, as well as individual provider reports and a lifecycle report for individual children.

- Query studios (also known as “datamarts”) are also available to HCD-IRSS users, to run custom queries in response to targeted research questions.

Data Entry and Reporting Requirements

Service and financial data is to be reported by PSL lead agencies into Transfer Payment Ontario (TPON) at an interim (end of Q2) and final (year-end) period, informed by key indicators from the PSL Monitoring Report in HCD-IRSS. By submitting their service and financial data in TPON, lead agencies are indicating to the ministry that their HCD-ISCIS data entry is completed. Lead agencies are to refer to their final Transfer Payment Agreement with MCCSS for more details on reporting requirements in TPON, including reporting due dates.

HCD-ISCIS Privacy Framework

A System Access Agreement (SAA) exists between MCCSS and PSL lead agencies, which outlines the privacy and security responsibilities of the ministry as the Health Information Network Provider (HINP) for HCD-ISCIS, as well as the responsibilities of the Lead Agencies as the users of the application and as Health Information Custodians (HICs).

Both a Privacy Impact Assessment (PIA) and Threat Risk Assessment (TRA) have been conducted on HCD-ISCIS, with regular updates as required.

As detailed in the SAA, PSL lead agencies are expected to implement policies and procedures to handle sensitive information and act according to the safeguards outlined in the Personal Health Information Protection Act, 2004.

HCD-ISCIS/IRSS Training and Technical Support

MCCSS does not offer formal training for HCD-ISCIS and HCD-IRSS. For support with data entry, online help is available within the HCD-ISCIS application. The following online materials are also available to users, that outline how to enter data in HCD-ISCIS and how to create, run and interpret the reports available in HCD-IRSS.

Please note that while the listed documents are the most current versions, there is some outdated information within, due to changes to the PSL program and the HCD-ISCIS and HCD-IRSS applications in recent years

| Document Name | Description |

|---|---|

| HCD-ISCIS Data Entry Training Manual | A detailed manual providing instructions on key data entry activities, including logging into HCD-ISCIS, exercises for entering key service data, business rules, and technical support. |

| HCD-ISCIS Training Slide Deck | A presentation deck providing helpful tips for data entry in HCD-ISCIS, including the navigating the application interface (menus and icons), the search function, shared consent, handling duplicates, inter-agency transfers, and working within the Case Activity Period (CAP). |

| HCD-ISCIS PSL User Guide | A detailed HCD-ISCIS manual specifically for PSL users, providing instructions on key data entry activities. |

| PSL Field Definitions and Business Rules | Field Definitions and business rules for PSL program clinical staff when using HCD-ISCIS. |

| HCD-ISCIS Overview for PSL/IHP/ Users | A high-level instruction manual for PSL/IHP/PSL users, with instructions on using HCD-ISCIS for reporting, including monitoring and pre-defined reports, custom (ad hoc) reports, and query studio basics. |

| HCD-IRSS User Guide for PSL/IHP/ Users | A detailed manual for PSL/IHP/ users providing instructions on using HCD-IRSS, including working with advanced report options, report samples, and a data dictionary. |

| HCD-IRSS Cognos 11 Training Video | A training video providing instructions on how to navigate HCD-IRSS using the Cognos 11 interface. |

Additional questions about data entry into HCD-ISCIS or reporting in HCD-IRSS can be directed to the OPS IT Service Desk, which can be reached at opssd@ontario.ca or

Footnotes

- footnote[50] Back to paragraph Dear Everybody, Holland-Bloorview, https://deareverybody.hollandbloorview.ca/

- footnote[51] Back to paragraph Wabano Centre for Aboriginal Health. Creating Cultural Safety. Creating Cultural Safety (ontariomidwives.ca)

- footnote[52] Back to paragraph https://www.publichealthontario.ca/en/health-topics/health-equity

- footnote[53] Back to paragraph National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health, https://nccdh.ca/glossary/entry/marginalized-populations.

- footnote[54] Back to paragraph Dr. Imran Awan and Dr Irene Zempi, A Working Definition of Islamophobia. https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Religion/Islamophobia-AntiMuslim/Civil%20Society%20or%20Individuals/ProfAwan-2.pdf

- footnote[55] Back to paragraph Ontario Human Rights Commission, http://www.ohrc.on.ca/en/racial-discrimination-race-and-racism-fact-sheet

- footnote[45] Back to paragraph Bexelius, A., Brogren Carlber, E., & Löwing, K. (2018). Quality of goal setting in pediatric rehabilitation- a SMART approach. Child: Care, Health and Development, 44(6), 850-856. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12609

- footnote[56] Back to paragraph Social Work Network. Solution Focused Practice. https://www.socialworkers.net/post/what-is-solution-focused-practice

- footnote[57] Back to paragraph Social Care Institute for Excellence. Strengths-based approaches. Strengths-based approaches | SCIE

- footnote[58] Back to paragraph Merriam-Webster. Xenophobia. https://www.merriam-webster.com/words-at-play/xenophobia-and-racism-difference

- footnote[59] Back to paragraph See Appendix 1:Key Terms for definitions of terms used in this section.

- footnote[60] Back to paragraph ibid.

- footnote[61] Back to paragraph There is an inherent power imbalance between a service provider, clinician, and/or professional working with a child and their family, and this power imbalance can be compounded by the intersection of additional factors such as race, religion, disability, sexual orientation, and gender.

- footnote[62] Back to paragraph First Nations Health Authority, https://www.fnha.ca/wellness/wellness-and-the-first-nations-health-authority/cultural-safety-and-humility

- footnote[64] Back to paragraph Example provided by CHEO. See more at CHEO Preschool helps kick-start Malakai’s soccer career - CHEO.

- footnote[65] Back to paragraph Example provided by CHEO in which OT liased with PT and family regarding adapted biking equipment and PT investigated different adaptive seating systems that can be pulled behind a bike, liaised with OT and family to try to obtain equipment for hiking season. Example used with permission.

- footnote[66] Back to paragraph Sources include: Canadian Wait Time Alliance, Canchild, Children’s Mental Health Ontario, Ministry of Health, Health Quality Ontario, and PSL and CTC service providers across the province.

- footnote[67] Back to paragraph Rosenbaum, P. (2015). The ABCs of clinical measures. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 57(6), 496-496. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.12735

- footnote[68] Back to paragraph Year 2019 Position Statement: Principles and Guidelines for Early Hearing Detection and Intervention Programs (2019).The Journal of early Hearing Detection and Intervention, 4(2),1-44.

- footnote[69] Back to paragraph Simms, L., Baker, S., and Clark, M.D. (2013). Visual Communication and Sign Language Checklist. Sign Language Studies. 14(1), 101-124. Simms_Baker_Clark-VCSL-SLS-2013.pdf (gallaudet.edu)

- footnote[70] Back to paragraph Oddson, B., Thomas-Stonell, N., Robertson, B., and Rosenbaum, P. (2019). Validity of a streamlined version of the Focus on the Outcomes of Communication Under Six: Process and outcome. Child: Care, Health and Development, 45(4), 600–605. https://doi.org/10.1111/CCH.12669

- footnote[71] Back to paragraph Hidecker, M. J. C., Paneth, N., Rosenbaum, P. L., Kent, R. D., Lillie, J., Eulenberg, J. B., Chester, K., Johnson, B., Michalsen, L., Evatt, M., and Taylor, K. (2011). Developing and validating the Communication Function Classification System for individuals with cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 53(8), 704–710. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8749.2011.03996.x

- footnote[72] Back to paragraph Zimmerman, I. L., Steiner, V. G., nd Pond, R. E. (2011). Preschool Language Scale (5th ed.). Pearson

- footnote[73] Back to paragraph Fenson, L., Marchman, V. A., Thal, D. J., Dale, P. S., Reznick, J. S., nd Bates, E. (2006). MacArthur-Bates Communication Development Inventory (2nd ed.). Brookes Publishing Co.

- footnote[74] Back to paragraph Daub, O., nd Oram Cardy, J. (2021). Developing a spoken language outcome monitoring procedure for a Canadian early hearing detection and intervention program: Process and Recommendations. The Journal of Early Hearing Detection and Intervention, 6(1), 12–31. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/7917/

- footnote[75] Back to paragraph Daub, O., Cunningham, B.J., Bagatto, M., nd Oram Cardy, J. (2022). Usability and feasibility of a spoken language outcome monitoring procedure in a Canadian Early Detection and Intervention Program: Results of a 12-month pilot. Journal of Early Hearing Detection and Intervention, 7(1), 67-100. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/jehdi/vol7/iss1/8

- footnote[76] Back to paragraph Cunningham, B. J., Daub, O. and Oram Cardy, J. (2021). Implementing evidence-based assessment practices for the monitoring of spoken language outcomes in children who are Deaf or hard of hearing in a large community program. Canadian Journal of Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology, 45(1), 41-58. https://cjslpa.ca/files/2021_CJSLPA_Vol_45/CJSLPA_Vol_45_No_1_2021_1204.pdf

- footnote[77] Back to paragraph Cunningham, B. J., Daub, O. and Oram Cardy, J. (2019). Barriers to implementing evidence-based assessment procedures: Perspectives from the front lines in speech-language pathology. Journal of Communication Disorders, 80, 66-80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2019.05.001

- footnote[78] Back to paragraph The PPC is aligned with the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF).

- footnote[79] Back to paragraph Cunningham, B. J., Cermak, C., Head, J., and Oram Cardy, J. (2022). Developing the Profile of Preschool Communication (PPC): A tool for the collection of comprehensive clinical and outcome data in preschool speech-language service systems. Journal of Communication Disorders, 98, 106232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2022.106232

- footnote[80] Back to paragraph Cunningham, B. J., and Oram Cardy, J. (2021). Reliability of speech-language pathologists’ categorizations of preschoolers’ communication impairments in practice. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 30, 734–739. https://doi.org/10.1044/2020_AJSLP-20-00239

- footnote[81] Back to paragraph Cunningham, B. J., Kwok, E. L., Turkstra, L. and Oram Cardy, J. (2019). Establishing consensus about preschoolers’ speech-language impairments in a large-scale community program. Journal of Communication Disorders, 82, 105925. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2019.105925

- footnote[82] Back to paragraph Cunningham, B. J., Daub, O. and Oram Cardy, J. (2021). Implementing evidence-based assessment practices for the monitoring of spoken language outcomes in children who are Deaf or hard of hearing in a large community program. Canadian Journal of Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology, 45(1), 41-58. https://cjslpa.ca/files/2021_CJSLPA_Vol_45/CJSLPA_Vol_45_No_1_2021_1204.pdf

- footnote[83] Back to paragraph Moeller, M. P., Tomblin, J. B., Yoshinaga-Itano, C., Connor, C. M., and Jerger, S. (2007). Current state of knowledge: Language and literacy of children with hearing impairment. Ear and Hearing, 28(6), 740–753. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0b013e318157f07f

- footnote[84] Back to paragraph Moeller, M. P., Tomblin, J. B., Yoshinaga-Itano, C., Connor, C. M., and Jerger, S. (2007). Current state of knowledge: Language and literacy of children with hearing impairment. Ear and Hearing, 28(6), 740–753. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0b013e318157f07f

- footnote[85] Back to paragraph Zeng, B., Law, J., and Lindsay, G. (2012). Characterizing optimal intervention intensity: The relationship between dosage and effect size in interventions for children with developmental speech and language difficulties. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 14(5), 471–477. https://doi.org/10.3109/17549507.2012.720281

- footnote[86] Back to paragraph Frizelle, P., Tolonen, A.-K., Tulip, J., Murphy, C.-A., Saldana, D., and Mckean, C. (2021). The influence of quantitative intervention dosage on oral language outcomes for children with developmental language disorder: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 52, 738–754. https://doi.org/10.23641/asha

- footnote[87] Back to paragraph Warren, S. F., Fey, M. E., and Yoder, P. J. (2007). Differential treatment intensity research: A missing link to creating optimally effective communication interventions. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 13, 70–77. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrdd.20139

- footnote[88] Back to paragraph Tosh, R., Arnott, W., & Scarinci, N. (2107). Parent-implemented home therapy programmes for speech and language: A systematic review. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 52(3), 253-269. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12280

- footnote[89] Back to paragraph Williams, A. L. (2012). Intensity in phonological intervention: Is there a prescribed amount? International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 14(5), 456–461. https://doi.org/10.3109/17549507.2012.688866

- footnote[90] Back to paragraph Edeal, D. M., & Gildersleeve-Neumann, C. E. (2011). The importance of production frequency in therapy for childhood apraxia of speech. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20, 95–110. https://doi.org/10.1044/1058-0360(2011/09-0005)

- footnote[91] Back to paragraph Cummings, A., Giesbrecht, K., & Hallgrimson, J. (2021). Intervention dose frequency: Phonological generalization is similar regardless of schedule. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 37(1), 99–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265659020960766