Foundational program elements

Overview

The information that follows includes clinical evidence and best practices to support the delivery of the required program elements. Where examples in the Ontario context are available, these have been shared to help service provider organizations implement these guidelines.

Figure 2: Foundational Program Elements for PSL and Children's Rehabilitation Services

Image displays four different coloured boxes that are side by side and connected with a double-ended arrow labeled system level.

Foundational Program Elements:

- Child and Family-Centred: Families are supported through strengths-based and culturally safer services

- Seamless Service Delivery: Families experience integrated and equitable services

- Collaboration and Partnerships: Partners work collaboratively to support families

- Performance Measurement: Families experience high quality evidence-based services that are informed by data and outcome measurement

Child and family-centred, strengths-based and culturally safer services

Family-centred care

Family-centred care is an approach to care where the family is considered the expert on their child and is involved as an equal member of the care team. The family is also the driver of care based on their preferences, needs, and resources.

Family-centred care is grounded in the assumptions that parents know their children best, that each family is unique, that children’s abilities and functioning can be dependent on the family unit as a whole, and that early intervention services are key to building family and provider capacity.

PSL Lead Agencies and CTCs will be leaders and drivers of change, both within the organization and with service partners, towards a service culture that is:

- child- and family-centred

- strengths-based and solution-focused, and

- trauma-informed

and that promotes:

- equity

- anti-oppression

- anti-ableism, and

- anti-racism, including dismantling anti-Black and anti-Indigenous racism

See Appendix 2: Cultural Change Leadership for a description of requirements, consistent with those outlined in the SmartStart Hubs Policy and Practice Guidelines.

Strength-based F-words for child development

The F-words for Child Development

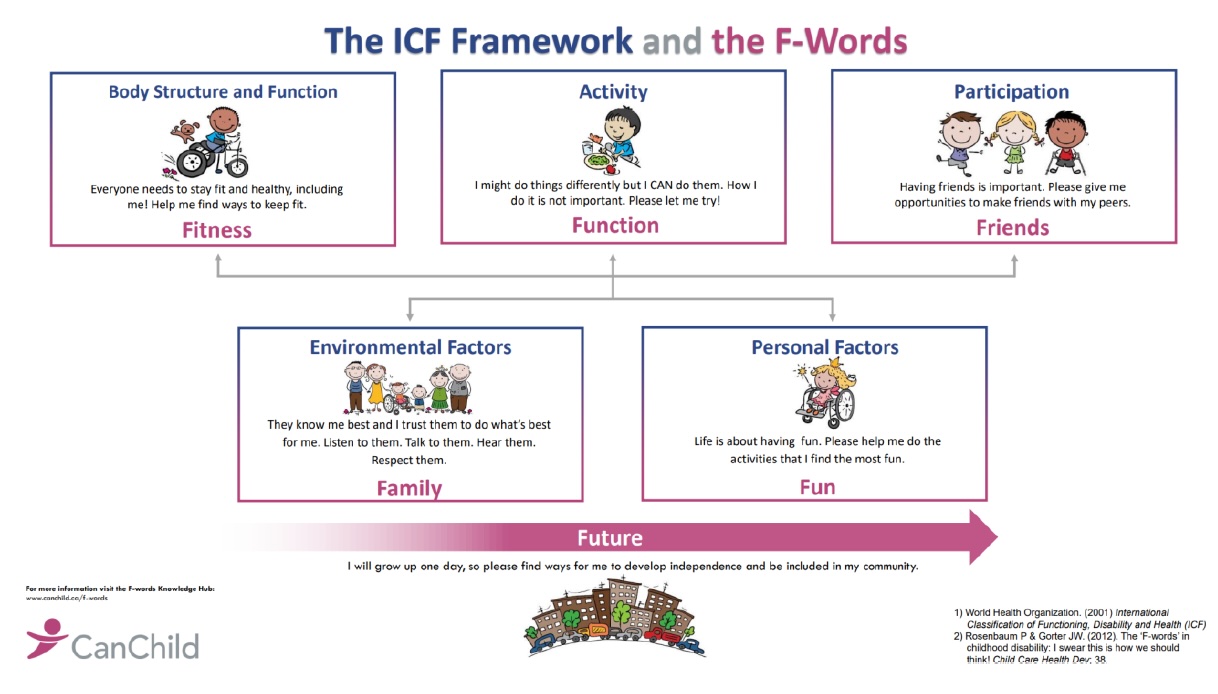

Figure 3: ICF Framework and the F-Words

Graphic provided by CanChild.

Fitness: Body Structure and Function - Everyone needs to stay fit and healthy, including me! Help me find ways to keep fit

Function: Activity - I might do things differently but I CAN do them. How I do it is not important. Please let me try!

Friends: Participation – Having friends is important. Please give me opportunities to make friends with my peers

Family: Environmental Factors – They know me best and I trust them to do what’s best for me. Listen to them. Talk to them. Hear them. Respect them

Fun: Personal Factors – Life is about having fun. Please help me do the activities that I find the most fun

Factors/Family, Personal Factors/Fun with an arrow depicting movement to the future.

- World health Organization. (2001) International Classification of Functioning. Disability and Health (ICF)

- Rosenbaum P & Gorter JW (2012). The ‘F-words’ in childhood disability: I swear this is how we should think! Child Care Health Dec; 38.

The F-words can be applied across all ages and developmental stages to promote a strengths-based, family-centred, holistic approach to service delivery by helping everyone focus on meaningful, functional goals and outcomes. Implementing the F-Words into practice supports family-centred planning and goal setting as well as collaboration with partners. Using the F-words for Child Development, service providers and families work together to take:

- A strengths-based approach that

- celebrates the ‘can do’ rather than the ‘cannot do’;

- addresses concerns and challenges, with children, youth, families, and service providers focused on positives and what is working well; and

- recognizes and leverages strengths to achieve goals.

- A family-centred focus that recognizes the needs and perspectives of both children and families, who are the ‘essential environment’ of all children.

- A holistic approach to child development and wellbeing that emphasizes the importance of looking at the full picture of a child and family (i.e., considering all components of the ICF/F-words and the connections between them).

- A focus on meaningful goal setting in which family participation is prioritized.

What’s happening in Ontario?

Many regions are already using F-words for Child Development to support goal setting and to develop care plans and other tools and resources. Several service providers have developed tools that are available for download.

Culturally safer services

Service providers are expected to develop supportive relationships in equity-deserving communities to build or strengthen all aspects of service delivery, and help families access other programs and services in their communities by supporting connections to the SmartStart Hubs and other agencies, as needed.

In addition to developing the supportive relationships with communities to promote dialogue about service systems and delivery, service providers should understand the demographics and the intersections of identities of the populations they serve (e.g., culture, language, geographic location, socio-economic factors) and be responsive to the linguistic and cultural needs of their communities.

One way to learn about communities is to gather information from available data sources or agencies, such as Statistics Canada, Ontario Demographics (including regional population projections by age) regional Early Development Instrument scores, local municipalities, or local Public Health Units. Another way is to identify and build relationships with local, grassroots and community-based organizations that serve equity-deserving groups.

Service provider organizations are encouraged to work with local First Nations, Métis, Inuit and urban Indigenous community organizations to discuss mechanisms to support self-identification for program planning and delivery of culturally safer and responsive services for children and families who are Indigenous. Service providers should consider working with organizations that have developed relationships with the local communities to leverage and build on the existing relationships to improve service delivery.

Health equity

Equity is created when everyone has a fair opportunity to reach their fullest potential. Evidence-informed tools and resources such as Ontario Health’s Equity, Inclusion, Diversity and Anti-Racism Framework, or the Ministry of Health’s Health Equity Impact Assessment (HEIA) can be used to identify how program implementation or program changes will impact population groups in different ways. This information can then be used when program planning to maximize positive impacts and reduce unintended negative impacts that could potentially widen health disparities between population groups.

Professional development and training

Professional development and training are essential to realizing a child- and family-centred approach. As outlined in Appendix 2: Cultural Change Leadership, service providers are required to provide specific staff training to support cultural change leadership, including anti-racism, bias awareness training, Indigenous cultural competency, F-words for Child Development training, solution-focused coaching, and trauma-informed service delivery approaches.

Service providers are expected to meet all professional college practice standards and guidelines from the College of Audiologists and Speech-Language Pathologists (CASLPO) or their respective Ontario professional college’s scope of practice, resource requirements, risk management, information management, privacy, competencies and procedures

Training and supports are provided through the ministry to build the capacity of service providers to better serve families and children throughout their service journey (e.g., online training for PSL professionals to deliver parent training supports in their communities, such as those provided by the Hanen Centre and Speech and Stuttering Institute). Other training and development requirements may be in place by service provider organizations.

As part of orientation, a training plan should be developed with new individual service providers to enable all required training to be completed in a timely manner. All regulated providers and supportive personnel should complete ministry training for service providers.

At a minimum, orientation training and supports should include all ministry resources for the following topic areas: program guidelines, Healthy Child Development-Integrated Services for Children Information System (HCD- ISCIS) and Healthy Child Development-ISCIS Reporting Sub-System (HCD-IRSS) for PSL providers, relevant outcome measures, and clinical guidance/pathways (e.g., Fluency, Motor Speech).

Service provider organizations are responsible for performance reviews, including reviews of clinical competency.

Seamless, streamlined, and integrated service delivery pathways

All families should experience equitable access to services through seamless, streamlined, and integrated pathways and feel supported and connected through their journey regardless of the local service system configuration for PSL programming and/or Children’s Rehabilitation Services.

To achieve this, the following need to be considered:

- Families experience seamless service delivery regardless of which provider in the system is approached first, and service gaps are minimized.

- Families experience streamlined service delivery where the number of steps is limited and the need for families to repeat key details of their story is minimized or eliminated.

- Families experience integrated service delivery when a continuum of services is available across programs and sectors that build on one another and service providers and families work together as a team to develop and support meaningful goals in a variety of contexts.

A service delivery pathway that uses a response to intervention (RTI) approach supports families and their child/youth to receive the right services at the right time. For more information on a RTI approach, see Assessment.

Clinical Service Pathways

Clinical service pathways, sometimes called clinical care pathways, are tools that support quality and seamless service delivery by outlining expectations and standardization for clinical practice, prioritization, and collaboration, as well as consideration of the family experience, for specific needs/populations.

Implementation Expectations:

Service providers should consider the following to meet ministry requirements when implementing clinical service pathways:

- Alignment within catchments to support consistency throughout the entire service delivery pathway (from intake to transition/discharge).

- Provision of flexible and responsive services to enable individual providers to meet the unique needs of children and families.

- Use of a tiered approach to service delivery (see Response to Intervention Approach – Tiered Service Model).

- Use of common definitions for needs/populations, developed collaboratively in local catchments, especially when service pathways include streaming needs/populations to a specific service provider.

- Coordination with other programs across the service system, for example at intake and transition/discharge, including education and health partners.

- Collaboration extends to other MCCSS-funded services for children with disabilities and/or with risk (e.g., Infant and Child Development Program, Healthy Babies Healthy Children, and Ontario Autism Program) as well as other rehabilitation support providers (e.g., District School Boards and Home and Community Care Services).

For PSL Service Providers

Types of Pathways

The following six broad clinical service pathways are recommended as a starting point in the development of local clinical service pathways for the PSL program and build on existing protocols as well as a tiered approach to service delivery:

- Permanent hearing loss (PHL) pathway

- Language difficulty/disorder pathway (includes expressive and receptive language)

- Social communication pathway

- Articulation/phonology pathway

- Motor speech pathway

- Fluency pathway

See Preschool Speech and Language Outcome Measure Guide, 2015 - page 5 for clinical definitions to support these pathways.

Emergent literacy skills, including phonological awareness, print knowledge, and story grammar have not been included as a separate clinical pathway and should be integrated into all other pathways, as appropriate.

Since specific clinical needs must be identified to stream children to an appropriate clinical service pathway, pathways often begin after assessment but could occur as early as intake, when possible. Children may move between pathways as needs are identified and prioritized.

- In these cases, intervention options across both clinical service pathways should be considered and prioritized according to the needs of the child and preferences of the family.

For example, though children with permanent hearing loss will be streamed to the permanent hearing loss (PHL) clinical service pathway as soon as hearing loss is identified, another clinical need may also be identified (e.g., social communication).

Age-based interventions

Services for children under 30 months should focus on building parent and caregiver capacity through a variety of Tier 2 interventions, such as monitoring, home programs, parent training and caregiver consultation.

For some young children, Tier 3 individual therapy sessions are required. For example, children with permanent hearing loss may receive Tier 3 services as infants/toddlers, given the risk of speech and language difficulties among children who are D/deaf or hard of hearing.

Once children are over 30 months, intervention options within clinical service pathways may include child-based interventions as well as parent- and caregiver-focused interventions depending on needs.

Managing wait experiences

Some families may experience waits in their service journey, which can be stressful, frustrating, and disruptive, both for families and service providers. It is essential that needs are identified and addressed as early as possible to optimize the key developmental windows of opportunity, as well as to set the foundation upon which improved functioning and participation can be achieved through the life course. It is also important that families who are waiting for services continue to be supported by helping them to build on existing skills.

Implementation expectations

Service providers are expected to provide an equitable and integrated wait management approach, with the following operational considerations:

- Wait experiences are measured, monitored, and managed across service locations, and service providers and disciplines so some families are not waiting longer than others within the same catchment for similar types of services.

- Tiered services are provided so families access the right services at the right time, depending on needs.

- Consistent strategies are used for prioritization within the catchment.

Service providers should plan together, identify bottlenecks in the service flow, and implement strategies to manage wait times across service providers, locations, or intervention type (including assessments) to better serve families within the catchment. When families require services from more than one provider or discipline (e.g. speech-language pathology services from PSL partner and occupational therapy services from a CTC) or transfer from one provider to another at key transition points (e.g. at school start), wait list management is encouraged to support consistent triaging and to mitigate circumstances in which families are on several waitlists or need to restart waitlist processes.

Service providers should continuously implement innovative approaches and make operational decisions to use their resources more efficiently, manage service pressures and reduce wait times at various points in their service delivery model or through the service system. CanChild’s Family-Centred Strategies for Waiting Lists

Virtual service delivery

Whenever possible, service provider organizations are encouraged to maintain a hybrid model of both virtual and in-person services to support a flexible, child- and family-centred approach to service delivery.

For PSL service providers

Research shows virtual intervention to be comparable in effectiveness to in-person therapy for speech outcomes in children as young as 4 years,

When determining whether to offer intervention services virtually or in-person, service providers should consider the best available research evidence, family choice, and clinical factors.

- The service provider’s knowledge, skills and experience and availability of technical support.

- The reason for the visit (e.g. parent coaching or consultation vs. hands-on direct therapy with the child).

- Family factors (e.g. comfort with technology, who will be involved), and child factors (e.g., comfort in clinic environment).

- Logistical factors (e.g. setting, access to technology).

footnote 32 ,footnote 33 ,footnote 34

Planning may be needed to address logistical factors, such as specific setting requirements. For example, with respect to school-based delivery of Children’s Rehabilitation Services, CTCs should engage the principal or designate to ensure the model of virtual service delivery can be supported by the school (e.g., space, technology, and supervision).

Collaboration and partnerships

Service providers play an essential role in coordinated early identification and intervention supports for children and youth who may have developmental difficulties. Interprofessional collaboration is a foundational element among regulated health professionals, educators, and other children’s services providers, irrespective of the settings in which they operate.

The ministry expects service providers to engage as leaders and collaborators with broader service system partners in the planning and delivery of child-centred services and supports as early as possible. This approach ensures that services are wrapped around the needs of children and families and provided through streamlined clinical service pathways as early as possible to optimize children’s health, wellbeing, and capacity.

Many communities have planning tables and formal partnership agreements that help them work together on key priorities. Establishing formal mechanisms for community planning and defining roles and responsibilities with community partners is an effective best practice. Formal agreements can also be leveraged and built upon to establish additional clarity on roles and responsibilities as needed.

Early identification and intervention system leadership

To support early identification and intervention, service provider organizations must work collaboratively across sectors to raise awareness, build capacity and support alignment among related sectors and services.

The following section references various sectors and partners with whom service providers may have agreements and/or collaborate in local planning and service delivery. It is not meant to be an exhaustive list, and other service providers may also be engaged depending on local circumstances.

Community early years and family supports

Service providers should be aware of and maintain connections with child- and family-serving partners to enable timely referrals to additional supports or specialized services, e.g., infant and children’s mental health services, child protection, EarlyON Child and Family Centres, specialized pediatric and primary care, and other programs and services in the community.

Service providers should consider the use of early identification tools and connections to primary health care providers delivering the Enhanced 18-Month Well-Baby Visit and public health units that provide Healthy Babies Healthy Children, parenting supports and other population-based programs in order to strengthen early identification opportunities and pathways.

There are also opportunities for collaboration with Infant and Child Development (ICDP) providers to support coordinated service delivery, particularly for the delivery of Tier 2 and 3 services.

Indigenous service providers

Building relationships with First Nations, Métis, Inuit and urban Indigenous communities will be critical to providing culturally safer services to First Nations, Métis, Inuit and urban Indigenous children, youth, and their families.

Aligned with expectations outlined in the SmartStart Hubs Policy and Practice Guidelines, service provider organizations will be expected to work with local Indigenous communities and local urban Indigenous service providers. See Appendix 2: Cultural Change Leadership for a description of requirements.

Inclusive of this collaborative work, service provider organizations and representatives from local First Nations, Métis, Inuit, and urban Indigenous communities are encouraged to discuss mechanisms to support Indigenous self-identification.

SmartStart hubs

CTCs and PSL Lead Agencies have specific responsibilities as defined through the SmartStart Hubs Policy and Practice Guidelines and PSLs are expected to enter into formal agreements to define processes and protocols for information sharing and supporting seamless and timely connections for families. See Access and Intake for further details.

Coordinated Service Planning (CSP)

Service provider organizations will partner with Coordinating Agencies in delivering Coordinated Service Planning (CSP) in accordance with locally developed formal agreements.

This includes supporting clear referral processes and information sharing among relevant providers and may include reporting requirements to support performance measurement and participation in cross-sectoral steering mechanisms.

CTCs and PSL service providers are expected to participate in a CSP team for families receiving CSP services who have requested their participation. For more information see Coordinated Service Planning: Policy and Program Guidelines 2017.

Ontario Autism Program

PSL and Rehabilitation Services are often provided to families prior to a diagnosis of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), enabling service providers to play a key role in supporting families to access ASD Diagnostic Hubs, AccessOAP and OAP services.

In some regions, PSL service provider organizations also provide OAP services, such as caregiver-mediated early years programs, the entry to school program, and urgent response services. PSL Lead Agencies will work collaboratively with OAP providers to coordinate services when families access services delivered by multiple programs. For more information about the OAP, see Ontario Autism Program.

Collaboration with district school boards for services in schools

Service providers are expected to collaborate to develop an approach to warmly transition children to school-based services at school start, and/or to meet the needs of students through the delivery of a continuum of children’s rehabilitation services. See Supportive Transitions for details.

In areas where more than one organization is providing services, such as a PSL provider and a District School Board (DSB), wherever possible and appropriate, students should receive a single intervention from a single therapist, in alignment with best practices and in support of service continuity, achievement of goals for students, and coordination of their clinical service plan and Individual Education Plan. For example, one speech-language pathologist would support speech and language services.

The Ministry of Education provides additional guidance to DSBs regarding delivery of services in school settings in applicable Policy & Program Memoranda, including PPM 81 and PPM 149. In catchments where DSBs directly deliver speech-language pathology, occupational therapy, and physical therapy services, collaboration between service providers and DSBs is expected in accordance with existing EDU Policy/Program Memoranda and legislation, as applicable.

Collaboration includes alignment with transition processes and service delivery expectations as outlined by the Ministry of Education with respect to Provincial and Demonstration Schools as required.

What’s happening in Ontario

PSL providers have emphasized the importance of system level integration and planning to maximize efficiencies, e.g. coordination of service delivery with the OAP.

Joint transition-to-school committees between PSLs, CTCs and District School Boards can support the development of transition protocols to enable smooth transitions for children entering junior kindergarten, continuity in service provision, and information sharing among partners and families.

For example, Calling all Three Year Olds is a collaborative network of early years providers who come together to help prepare children and their parents to start school.

Performance measurement and reporting

Performance measurement framework

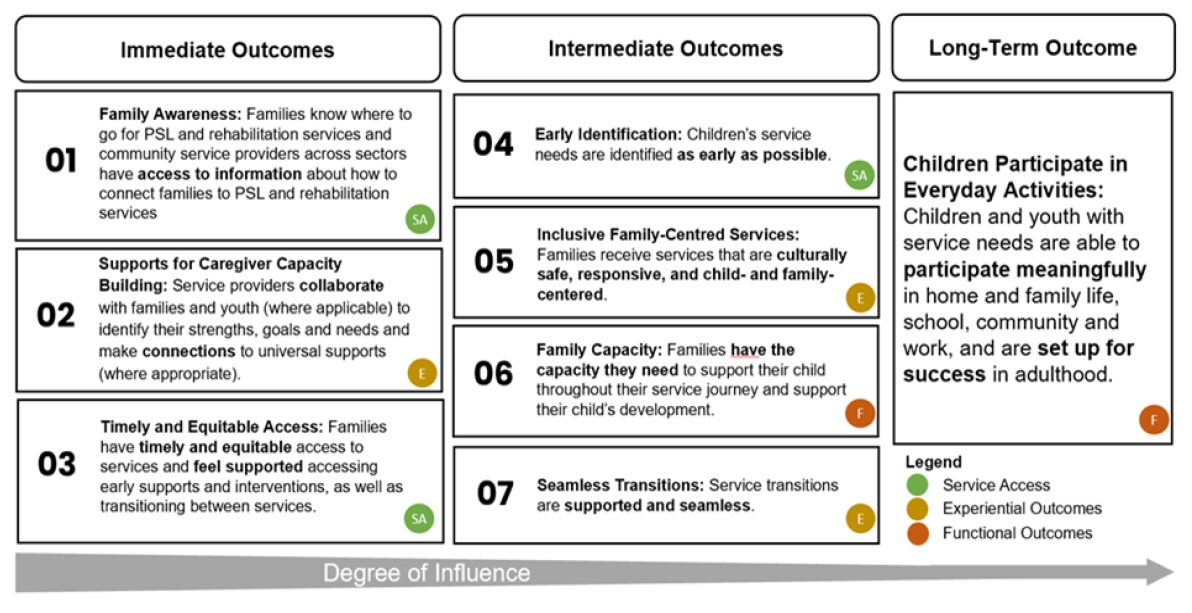

Measuring the outcomes and impact of services is crucial to supporting service providers and the ministry to determine the extent to which the intended goals of programs are being met. Building on measures and indicators currently collected across early intervention and special needs programs, the ministry is pursuing greater alignment across programs by identifying common measures related to service access, experiential, and functional outcomes, as illustrated in Figure 4.

Through regular data reporting by service provider organizations, the ministry will continue to lead the implementation and measurement of common outcomes in the following three outcome domains:

Figure 4: Intended Outcomes for PSL and Rehabilitation services

Image contains the following text: From larger to smaller degree of influence:

Immediate Outcomes:

- Family Awareness: Families know where to go for PSL and rehabilitation services and community service providers across sectors have access to information about how to connect families to PSL and rehabilitation services. (Service Access)

- Supports for Caregiver Capacity Building: Service providers collaborate with families and youth (where applicable) to identify their strengths, goals and needs and make connections to universal supports (where appropriate). (Experiential Outcomes)

- Timely and Equitable Access: Families have timely and equitable access to services and feel supported accessing early supports and interventions, as well as transitioning between services. (Service Access)

Intermediate Outcomes:

- Early Identification: Chidren’s service needs are identified as early as possible. (Service Access)

- Inclusive Family-Centred Services: Families receive services that are culturally safe, responsive, and child- and family-centred. (Experiential Outcomes)

- Family Capacity: Families have the capacity they need to support their child throughout their service journey and support their child’s development. (Functional Outcomes)

- Seamless Transitions: Service transitions are supported and seamless. (Experiential Outcomes)

Long-term Outcome:

- Children Participate in Everyday Activities: Children and youth with service needs are able to participate meaningfully in home and family life, school, community and work, and are set up for success in adulthood. (Functional Outcomes)

For Children’s Rehabilitation Services: The performance measurement approach described in this section, together with the performance measurement approach described in the SmartStart Hubs Policy and Practice Guidelines (2022), will enable the ministry to monitor performance of Children’s Rehabilitation services in an integrated way.

Roles and responsibilities

Performance measurement is a shared responsibility of service providers and the ministry.

The ministry is committed to fostering a culture of continuous quality improvement where:

- performance is assessed using a range of qualitative and quantitative measures

- improvements are continuous and incremental

- service providers can identify and implement opportunities for improvement in response to their data and front-line service experience

- quality improvement plans are aligned to the goals of the Performance Measurement Framework; and

- effective and efficient use of resources can be demonstrated

The ministry will continue to develop and refine reporting requirements to monitor performance that supports common outcome measurement across the sector. Where possible, provincial data will be shared with service providers to demonstrate collective achievements of program and service system outcomes.

Within this framework, the ministry will be developing a strategy to identify and address inequities to accessing early intervention and special needs services using an intersectional lens. Service providers implementing identity-based data collection are encouraged to review Ontario’s Data Standards for the Identification and Monitoring of Systemic Racism.

Ministry expectations for performance monitoring

The ministry expects service providers to report on selected service data (including targets), experiential and functional outcomes, and to provide contextual information through supplementary narrative reports where required.

Service providers are responsible for reporting data in accordance with provincial expectations outlined in Service Agreements with the ministry. Service providers are expected to use data to inform continuous quality improvement including improvements to internal processes and policies, in keeping with the parameters of these guidelines, other protocols, contractual requirements, and other ministry guidance.

Service data

Quantitative service data related to clients served, demand, utilization and wait times for service provision will be reported to the ministry by service providers of both programs. These foundational measures enable the ministry to quantify demand and capacity in the system, identify trends, and evaluate the impact of investments.

Children’s Rehabilitation Services: Service providers will report Children’s Rehabilitation Services data to the ministry through Transfer Payment Ontario (TPON) at regular reporting periods and as defined by the ministry.

Please refer to the Services Objectives Document in TPON for reporting requirements and data element descriptions.

Preschool Speech and Language Program: Early Intervention programs including PSL are monitored through service data entered into the Healthy Child Development-Integrated Services for Children Information System (HCD-ISCIS). Select PSL service data elements are also reported in TPON from the Program Monitoring Report. Please refer to the Services Objectives Document in TPON for reporting requirements and data element descriptions.

See Appendix 8: HCD-ISCIS and IRSS- Training Overview and Resources

Performance measurement is a continuous and incremental process of improvement to achieve the objectives within the Early Intervention and Special Needs Performance Measurement Framework. Priorities include monitoring trends associated with access to services for equity-deserving populations, understanding families’ experience of programs to inform quality improvement, measuring resource intensity and system efficiency, and measuring the provision of Tier 1/Universal supports in schools and communities and the impact on waitlists.

Targets

Standardized targets support consistent service delivery experiences for families and enable performance measurement by the ministry and service providers for continuous quality improvement.

In alignment with other Early Intervention and Special Needs programs, provincial service targets for Rehabilitation Services will be established for the number of days waiting from (1) referral to initial assessment and (2) initial assessment to service initiation. Additional targets will include those associated with improving family experiences for those receiving or waiting for services, and other priorities as identified through the Early Intervention and Special Needs Performance Measurement Framework that supports continuous quality improvement.

The PSL program is currently monitored through service targets in the following core areas:

- Wait times from referral to initial assessment

- Wait times from referral to first intervention

- Delivery of parent training

- Completion and frequency of outcome measures

Additional details about service targets, as applicable, are reflected in Service Agreements with the ministry.

Additional targets may include those associated with improving family experiences for those receiving or waiting for services, and other priorities as identified through the Performance Measurement Framework that supports continuous quality improvement.

Family experience data

Service providers are expected to actively solicit information from families to help understand their service experience. When doing so, they will obtain informed consent by clearly explaining how the data will be handled, shared, and used and addressing any concerns regarding potential risks (privacy) and benefits (supporting planning and continuous quality improvement).

As part of the experiential component of the Early Intervention and Special Needs Performance Measurement Framework (Figure 4), the ministry will be developing an approach to collect standardized family experience data across early intervention and special needs programs and services to improve experiential outcomes for families. Family experience data will help the ministry to better understand program delivery, help ensure consistency in how services are delivered, and monitor service quality across the province.

Functional outcome measurement

The ministry expects service providers to select and utilize appropriate tools and to work with families to help identify goals and inform interventions that will optimize participation of children and youth at home, in school, and in the community. The ministry will work with service providers to develop a consistent approach to monitor the perception and achievement of goals and/or functional improvement in various functional domains for children receiving rehabilitation services.

Functional outcome measurement for children without permanent hearing loss

PSL providers are required to use the Focus on the Outcomes of Communication Under Six (FOCUS-34) tool to evaluate change in communicative participation in preschool children (without permanent hearing loss) who access services. The FOCUS tool captures ‘real world’ changes in children’s communication skills following speech and language treatment. More specifically, the FOCUS assesses how children use their communication to participate at home, school, and in the community in alignment with the participation component of the ICF framework. PSL providers are also required to use the Communication Function Classification System (CFCS) to describe children’s functional communication level. Together, data from the FOCUS-34 and CFCS can be used to better understand children’s functional outcomes.

See Appendix 6: PSL Outcome measurement and monitoring

Program-level outcome monitoring for children with permanent hearing loss

PSL providers are expected to use the Preschool Language Scale, 5th Edition (PLS-5) and MacArthur-Bates Communication Development Inventories, 2nd Edition (MBCDI-2). These are standardized tests that are used for program-level outcome monitoring for children with permanent hearing loss who are accessing spoken language services. The PLS-5 assesses children’s developmental language. The MBCDI-2 captures information about children’s early language (e.g., expressive and receptive vocabulary). These tools are focused on measurement within the Body Functions and Structures and Activity components of the ICF framework and may be used to compare children’s skills to those of their same age peers.

See Appendix 6: PSL Outcome measurement and monitoring

Supplementary reporting

Service providers are expected to submit supplementary narrative reports to the ministry where required. Qualitative information collected through supplementary reports enables service provider organizations to reflect on the services delivered over the prior year and explain and/or supplement the quantitative service data submitted to provide a holistic view of the organization’s performance and implementation of the guidelines. The ministry uses these reports to support regional program oversight, to identify key trends across the province, and inform program policy and performance measurement. Through supplementary reports, service providers may be asked to report on implementation progress in key areas, quality improvement plans and/or mitigation strategies for measuring performance against program-level targets, and to provide additional context as appropriate.

Footnotes

- footnote[16] Back to paragraph Paul, D., & Roth, F. P. (2011). Guiding principles and clinical applications for Speech-Language Pathology practice in early intervention Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 42, 320–330.

- footnote[17] Back to paragraph Law, M., Rosenbaum, P., King, G., King, S., Burke-Gaffney, J., Moning-Szkut, T., Kertoy, M., Pollock, N., Viscardis, L., & Teplicky, R. (2003). What is Family-Centred Service?

- footnote[18] Back to paragraph Cunningham, B. J. & Rosenbaum, P. L. (2014). Measure of processes of care: A review of 20 years of research. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 56(5), 445-452.

- footnote[19] Back to paragraph Originally named the F-words in Childhood Disability in 2011, renamed in 2021.

- footnote[20] Back to paragraph World Health Organization. (2001). International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) (who.int)

- footnote[21] Back to paragraph Practice Standards and Guidelines for the Assessment of Children by Speech-Language Pathologists (2018). The College of Audiologists and Speech-Language Pathologists of Ontario. PSG_EN_Assessment_Children_by_SLPs.pdf (caslpo.com)

- footnote[22] Back to paragraph Could include multiple providers in a regional consortia, such as Consortium pour les élèves du nord de l'Ontario (CÉNO) which serves six Francophone school boards and their communities in the provision of specialized French-language services to support students with special needs.

- footnote[23] Back to paragraph Rotter T., de Jong R.B., Lacko S.E., Ronellenfitsch, U., & Kinsman, L. (2019). Clinical pathways as a quality strategy. In: Busse R, Klazinga N, Panteli D, et al., editors. Improving healthcare quality in Europe: Characteristics, effectiveness and implementation of different strategies [Internet]. Copenhagen (Denmark): European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies 53(12). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549262/

- footnote[24] Back to paragraph Law M., Rosenbaum, P., King G., King, S., Burke-Gaffney, J., Moning-Szkut, T., Kertoy, M., Pollock, N., Viscardis, L. & Teplicky, R. (2003). Facts, concepts, strategies sheets: Family-centred strategies for waiting lists. CanChild Centre for Childhood Disability Research, McMaster University

- footnote[25] Back to paragraph Kollia, B., & Tsiamtsiouris, J. (2021). Influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on telepractice in speech-language pathology. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 49(2), 152–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/10852352.2021.1908210

- footnote[26] Back to paragraph Standards for Virtual Care In Ontario by CASLPO Audiologists and Speech-Language Pathologists. (2020). College of Audiologists and Speech-Language Pathologist of Ontario.

- footnote[27] Back to paragraph Adopting and Integrating Virtual Visits into Care: Draft Clinical Guidance. For Health Care Providers in Ontario (2020). Health Quality Ontario

- footnote[28] Back to paragraph Grogan-Johnson, S., Alvares, R., Rowan, L., & Creaghead, N. (2010). A pilot study comparing the effectiveness of speech language therapy provided by telemedicine with conventional on-site therapy. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 16, 134–139. https://doi.org/10.1258/jtt.2009.090608

- footnote[29] Back to paragraph Ganek, H., & Oram Cardy, J. (2021). Exploring speech and language intervention for preschoolers who are deaf and hard of hearing: A scoping review. The Journal of Early Hearing Detection and Intervention, 6(2), 87–100. https://doi.org/10.26077/0e75-07f0

- footnote[30] Back to paragraph Hao, Y., Franco, J. H., Sundarrajan, M., & Chen, Y. (2021). A pilot study comparing tele-therapy and in-person therapy: Perspectives from parent-mediated intervention for children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51(1), 129–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04439-x

- footnote[31] Back to paragraph Sackett, D. L., Rosenberg, W. M., Gray, J. A., Haynes, R. B., & Richardson, W. S. (1996). Evidence based medicine: What it is and what it isn’t. British Medical Journal, 312, 71–72. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71

- footnote[32] Back to paragraph Camden, C., & Silva, M. (2021). Pediatric telehealth: Opportunities created by the COVID-19 and suggestions to sustain its use to support families of children with disabilities. Physical and Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics, 41(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01942638.2020.1825032

- footnote[33] Back to paragraph Rosenbaum, P., Silva, M., & Camden, C. (2021). Let’s not go back to ’normal’! lessons from COVID-19 for professionals working in childhood disability. Disability and Rehabilitation, 43(7), 1022–1028. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1862925

- footnote[34] Back to paragraph Kwok, E. Y. L., Pozniak, K., Cunningham, B. J., & Rosenbaum, P. (2022). Factors influencing the success of telepractice during the COVID-19 pandemic and preferences for post-pandemic services: An interview study with clinicians and parents. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 57(6), 1354-1367. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12760