Nitrogen dioxide

Nitrogen dioxide is a reddish-brown gas with a pungent odour, which transforms in the atmosphere to form gaseous nitric acid and nitrates. It plays a major role in atmospheric reactions that produce ground-level ozone, a major component of smog. Nitrogen dioxide also reacts in the air and contributes to the formation of PM2.5 (Seinfeld and Pandis, 2006). Combustion or burning in air produces nitrogen oxides (NOx), of which NO2 is a component. Major sources of NOx emissions include the transportation sector, industrial processes and electric power generation.

In addition to its role in the formation of ground-level ozone, nitrogen dioxide can irritate the lungs and lower resistance to respiratory infection. People with asthma and bronchitis have increased sensitivity to NO2. Nitrogen dioxide chemically transforms into nitric acid in the atmosphere and, when deposited, contributes to the acidification of lakes and soils in Ontario. Nitric acid can also corrode metals, fade fabrics, degrade rubber, and damage trees and crops.

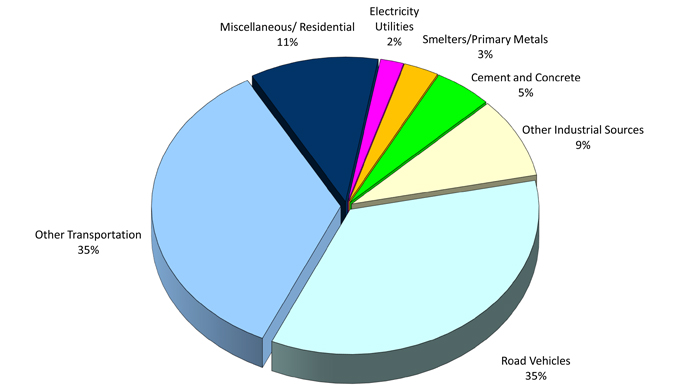

Figure 1 shows the estimates for Ontario’s NOx emissions from point, area and transportation sources for 2017. The transportation sectors accounted for approximately 70% of NOx emissions (Air Pollutant Emission Inventory 1990-2017, 2019).

Figure 1: Ontario nitrogen oxides emissions by sector (2017 estimates for point/area/transportation sources)

Road vehicles: 35%, other transportation: 35%, miscellaneous/residential: 11%, other industrial sources: 9%, cement and concrete: 5%, smelters/primary metals: 3%, electricity utilities: 2%

Note: Excludes emissions from open and natural sources.

There were no exceedances of the provincial one-hour and 24-hour AAQC for NO2, 200 ppb and 100 ppb, respectively, at any of the Ministry’s AQHI air monitoring stations in Ontario during 2017. The Toronto West air monitoring station, located in an area of Toronto influenced by significant vehicular traffic, recorded the highest NO2 annual mean (15.0 ppb) during 2017; whereas rural sites Port Stanley and Parry Sound recorded the lowest NO2 annual mean (2.7 ppb). The highest NO2 means were recorded in large urbanized areas, such as the Greater Toronto Area of southern Ontario. The Barrie station recorded the highest one-hour NO2 concentration (64 ppb), and Toronto West recorded the highest 24-hour NO2 concentration (41 ppb). A summary of the 2017 NO2 annual statistics for individual AQHI air monitoring stations in Ontario are presented in Table A3 of the Appendix.

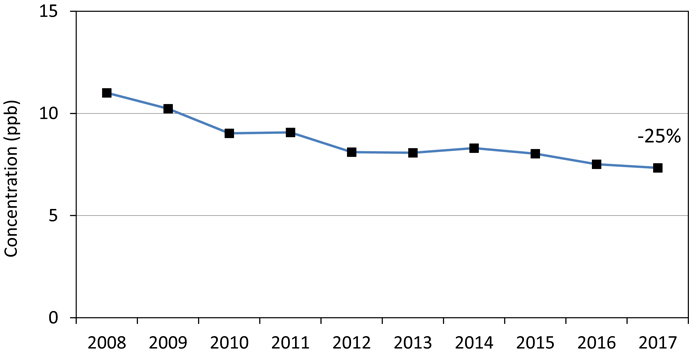

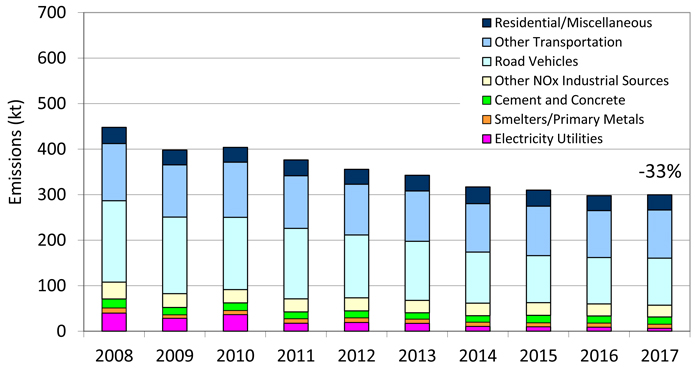

The NO2 annual mean concentrations across Ontario have decreased 25% from 2008 to 2017, as displayed in Figure 2. NO2 10-year trends for individual AQHI air monitoring stations in Ontario are presented in Table A11 of the Appendix. The NOx emission trend from 2008 to 2017 indicates a decrease of approximately 33% as shown in Figure 3 (Air Pollutant Emission Inventory 1990-2017, 2019).

Figure 2: Trend of NO2 annual means across Ontario (2008-2017)

The nitrogen dioxide annual mean concentrations across Ontario have decreased 25% from 2008 to 2017.

Note:

10-year trend based on data from 31 ambient air monitoring stations.

Ontario does not have an annual AAQC for NO2

Figure 3: Ontario NOx emission trend (2008-2017)

The nitrogen oxides emission trend from 2008 to 2017 indicates a decrease of approximately 33%.

Note: Excludes emissions from open and natural sources.

Ontario’s emissions trading regulations on sulphur dioxide and nitrogen oxides (O. Reg. 397/01 and O. Reg. 194/05) introduced in the early 2000s have contributed to the reduction in nitrogen oxides emissions, particularly in the early years of the program. Nitrogen oxides emissions from on-road vehicles have also decreased due to the phase-in of new vehicles having more stringent emission standards. While the implementation of Drive Clean helped reduce the NOx emissions from passenger vehicles, after 20 years, it was no longer effective and no longer provided value for tax payers. As a result, the program has been discontinued for passenger vehicles.

Emissions from heavy-duty vehicles however have not decreased as rapidly. Heavy-duty vehicles remain a significant source of nitrogen oxides, a pollutant that contributes to smog formation, and fine particulate matter. Ontario is developing an enhanced and redesigned emissions testing program to target heavy-duty vehicles to further reduce pollutants in our air.