2023 Apiculture winter loss report

2023 honey bee colony winter mortality

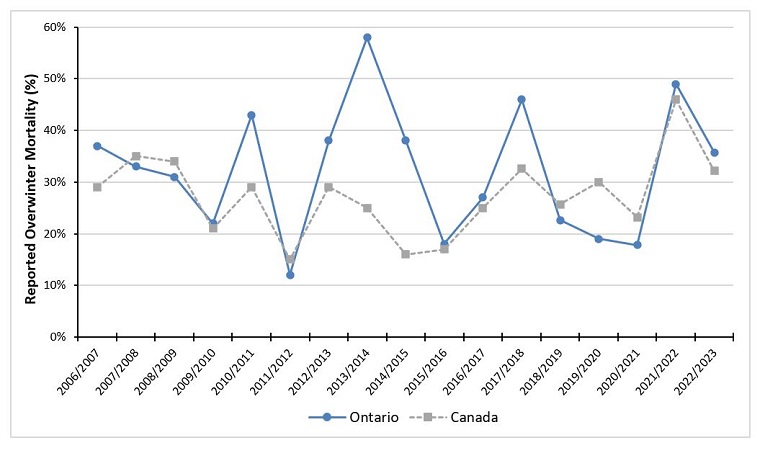

Overwinter mortality for 2022-2023 for commercial beekeepers operating in Ontario was estimated to be 36%, down from the 49% estimated for the winter of 2021-2022. The response from a single commercial beekeeper significantly influenced the final winter loss statistic for commercial beekeepers. Excluding this response, the overwinter mortality for commercial beekeepers drops to 17%.

The estimate for commercial beekeepers in Ontario was approximately 10% more than the estimated loss reported for small-scale beekeepers (26%).

The 2023 estimation for honey bee loss averaged between all of Canada was 32%.

Who we surveyed

In the spring of 2023, the survey was distributed via email to:

- 208 registered commercial beekeepers (defined as operating 50 or greater colonies)

- 2,550 registered small-scale beekeepers (defined as operating 49 or fewer colonies)

The survey was sent electronically to all registered beekeepers (commercial and small-scale) who provided the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA) with their email address.

The survey is voluntary and all responses are self-reported by beekeepers. Data is not verified by OMAFRA or any other independent body, though it is reported to the Canadian Association of Professional Apiculturists (CAPA), along with the data of other provinces for consolidation into a national report.

Responses were received from 72 commercial beekeepers and 488 small-scale beekeepers, which represents 20% of beekeepers who received the survey.

Of the beekeepers who were registered in Ontario as of December 31, 2022, responses were received from 35% of commercial beekeepers representing 35,276 colonies and from 19% of small-scale beekeepers representing 3,693 colonies (Tables 1 and 2). Combined, the responses represent 38% of the total number of colonies registered in 2022.

| Beekeeping regions | # of commercial beekeeper respondents | % of commercial beekeeper respondents | # of small-scale beekeeper respondents | % of small-scale beekeeper respondents |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central | 22 | 31% | 162 | 33% |

| East | 15 | 21% | 140 | 29% |

| North | 6 | 8% | 64 | 13% |

| South | 22 | 31% | 97 | 20% |

| Southwest | 7 | 10% | 25 | 5% |

| Beekeeper type | # of full-sized colonies put into winter in fall 2022 | # of viable overwintered colonies as of May 15, 2023 | # of non-viable colonies as of May 15, 2023 | Overwinter mortality (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial | 35,276 | 22,690 | 12,586 | 35.7% |

| Small-scale | 3,693 | 2,747 | 946 | 25.6% |

Results

The estimated overwinter honey bee mortality and the number of respondents varied by beekeeping region (Table 3). The majority of commercial beekeepers who responded to the survey were from the central and south beekeeping regions. These areas are known to have the greatest number of honey bee colonies in Ontario. Responses from small-scale beekeepers were largely from the central and east beekeeping regions (Table 1).

Commercial beekeepers reported the greatest losses in the south region while small-scale beekeepers reported the highest losses in the southwest region (Table 3). Mortality during the 2022-2023 winter differed between the beekeeper groups, with the commercial beekeepers being 10.1 percentage points higher than small-scale beekeepers (Table 2).

| Beekeeping region | # of commercial beekeeper respondents | Commercial beekeeper overwinter mortality (%) | # of small-scale beekeeper respondents | Small-scale beekeeper overwinter mortality (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central | 22 | 16.1% | 162 | 24.1% |

| East | 15 | 21.5% | 140 | 29.8% |

| North | 6 | 23.8% | 64 | 20.1% |

| South | 22 | 46.5% | 97 | 23.7% |

| Southwest | 7 | 13.4% | 25 | 32.2% |

| Total | 72 | 35.7% | 488 | 25.6% |

When respondents were grouped by operation size (number of colonies managed), the honey bee mortality during the winter of 2022-2023 ranged from 15.1% to 47.9% (Table 4). Beekeepers operating 501-1,000 colonies reported fewer honey bee colony losses (15.1%) than all other beekeeping operation sizes. Beekeepers with >1,000 colonies had the highest losses (47.9%), however, if the response from the one commercial beekeeper who significantly influenced the final winter loss statistic was excluded, the overwinter mortality for beekeepers operating >1,000 colonies decreases from 47.9% to 14.5%. Beekeepers with <10, 10-49, 50-200, and 201-500 colonies had moderately high losses, with 28.5%, 24.1%, 21.3%, and 20.4% overwinter mortality respectively.

| # of respondents | # of colonies reported in the fall of 2022 | Overwinter mortality (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 376 | <10 | 28.5% |

| 112 | 10-49 | 24.1% |

| 46 | 50-200 | 21.3% |

| 13 | 201-500 | 20.4% |

| 9 | 501-1,000 | 15.1% |

| 4 | >1,000 | 47.9% |

Main factors of bee mortality

Beekeepers were asked to report on what they believed were the main factors contributing to their overwinter honey bee mortalities; they were able to select as many reasons as they felt were applicable. These opinions may be based on observable symptoms or beekeeper experience, judgement or best estimate.

The most commonly reported factors influencing overwinter mortality (Table 5) by commercial beekeepers included:

- starvation

- weak colonies

- varroa (and associated viruses)

The most commonly reported factors influencing overwinter mortality (Table 5) by small-scale beekeepers included:

- weak colonies

- weather/climate

- starvation

28% of commercial beekeepers and 8% of small-scale beekeepers selected “other” for their suspected cause of colony loss. It is noted that 65% and 22% of the “other” responses were attributed to suspected pesticide poisonings by commercial and small-scale beekeepers, respectively.

In 2022, OMAFRA received 0 in-season honey bee mortality incident reports so it is surprising to see the number of survey respondents who reported suspected pesticide poisoning as a contributing factor to honey bee colony mortality during the winter. Either beekeepers experienced a noticeable pesticide or spraying incident and did not report it to OMAFRA or beekeepers may be citing unfounded events or assumptions that pesticides are the cause for their honey bee mortality.

While it is important to acknowledge concerns about suspected pesticide poisoning, it is vital that these incidents are reported to OMAFRA using the online form to report a significant honey bee mortality incident experienced during the active beekeeping season.

| Suspected cause(s) of colony loss | % of commercial beekeepers reporting | % of small-scale beekeepers reporting |

|---|---|---|

| Poor queens | 29% | 12% |

| Weak colonies | 35% | 23% |

| Weather/climate | 25% | 20% |

| Starvation | 40% | 15% |

| Varroa (and associated viruses) | 32% | 14% |

| Other* | 28% | 8% |

| Don’t know | 13% | 10% |

| Nosema | 8% | 2% |

*Some beekeepers who reported "other" provided multiple suspected causes of death in their response. Each beekeeper who reported "other" is only counted once.

Management practices for pests and disease

Varroa mites (Varroa destructor)

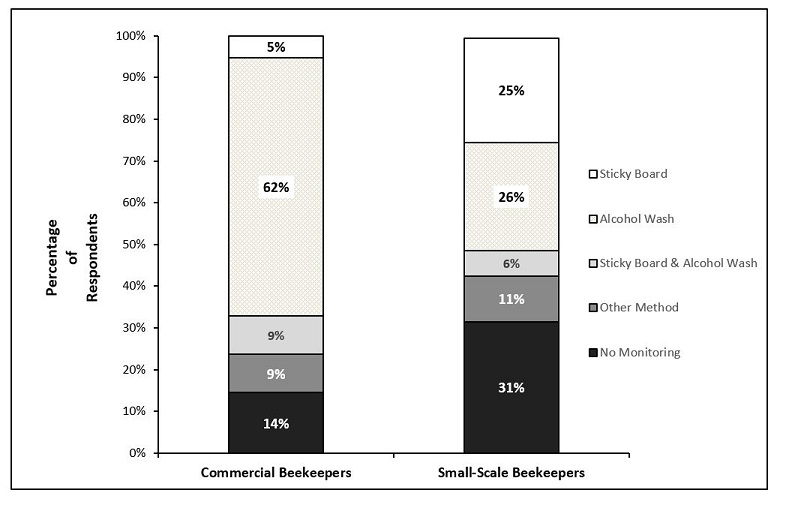

In this survey beekeepers were asked how they monitored for varroa mite infestations (Figure 1) and which treatments were used at the beginning (spring), mid-season and the end (late summer/fall) of the 2022 beekeeping season (Table 6).

Accessible description for Figure 1

Proportion of beekeepers monitoring for varroa mites

Of the beekeepers who responded to the varroa mite monitoring question, 86% of commercial beekeepers and 69% of small-scale beekeepers stated they monitor for varroa mite infestation in their colonies. Of those, several monitoring methods were used, the most common being either an alcohol wash or a sticky board.

Some beekeepers used more than 1 method to monitor for varroa mites. When the response “other” was selected, some beekeepers reported that they visually checked their colonies for varroa mites, 3% used the “sugar shake” method and 3% used the “CO2 roll” method. However, none of these methods are recommended or recognized as effective, as visually checking for mites is not proven to yield usable information, and the sugar shake and CO2 roll methods can be unreliable and are not tied to established thresholds for Ontario.

From the data, it appears that most (86%) of the commercial beekeepers represented by this survey are monitoring for varroa mites. This figure is up from the 79% of commercial beekeepers who reported they were monitoring for varroa mites in the 2021-2022 season. Compared to the 2021-2022 survey, the number of commercial beekeepers who do not monitor for varroa mites decreased by 7%. Likewise, most small-scale beekeepers (69%) reported monitoring for varroa mites in 2022-2023, which is more than the 62% of small-scale beekeepers who reported monitoring for varroa mites in the previous survey year (2021-2022).

It is encouraging that the proportion of responding beekeepers who sampled for varroa mites has increased since 2022. However, it is still concerning that a high percentage (14% commercial and 31% small-scale) of beekeepers who responded to the survey reported no monitoring for varroa mites at all. These numbers represent too high a proportion of beekeepers who are not monitoring for varroa mites, given the threat they pose to the industry overall. Ideally, 100% of beekeepers should monitor for varroa mites as monitoring, along with application of a treatment, is crucial for the management of this honey bee pest. Without the management of varroa mites, colonies are at a high risk of death and/or spreading varroa mites to other nearby colonies. Furthermore, research has demonstrated that inadequate varroa mite control is the primary cause of winter mortality in honey bee colonies in Ontario

These results demonstrate the need for further education/training of beekeepers and further messaging on best management practices and integrated pest management. Beekeeper monitoring for varroa mites needs to improve as this is a key practice to assess colony health and to improve the survival of colonies going into the winter. It is not enough that beekeepers simply treat their colonies without knowing their varroa mite levels.

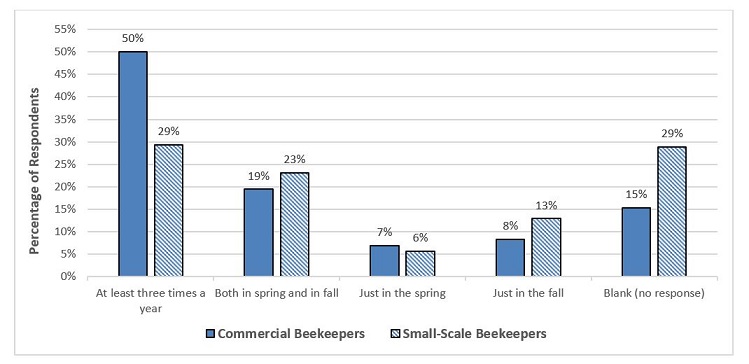

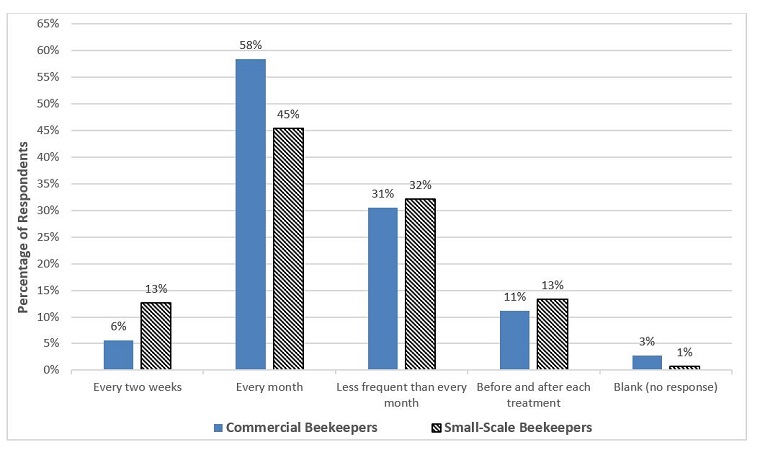

Frequency of monitoring for varroa mites

It is encouraging to see from the survey data that a good proportion of both commercial and small-scale beekeepers are sampling at least twice per season, and it is even more encouraging to see that there are both commercial and small-scale beekeepers sampling even more frequently at 3 times per year (Figure 2). A more detailed analysis of those beekeepers who sampled more than 3 times per year shows that 58% and 45% of commercial and small-scale beekeepers respectively sampled for varroa mites every month (Figure 3). At the same time there is room for improvement for both categories of beekeepers. Monitoring frequently, particularly as the beekeeping season progresses, is one of the most important management practices beekeepers can perform to ensure they are applying their varroa treatments in a timely manner and ultimately preventing damaging levels of varroa from occurring.

Accessible description for Figure 2

Accessible description for Figure 3

Treatments used to control varroa mites

Ontario beekeepers use a variety of treatment options to manage varroa mites (Table 6). The survey asked beekeepers to report their use of varroa mite treatment options during 3 periods in 2022: spring, mid-season and late summer/fall. These periods are defined as:

- Spring – from the end of winter to the start of the honey flow

- Mid-season – from the start to the end of the honey flow

- Late summer/fall – when the last supers were removed for honey production to when colonies were managed for winter

In spring of 2022, the most common method of varroa mite treatment reported by commercial beekeepers was use of Apivar® (39%), while in late summer/fall of 2022 both oxalic acid (53%) and Apivar® (50%) were most commonly used. The most common method of spring varroa mite treatment reported by small-scale beekeepers was use of Apivar® (24%) and Formic Pro (22%), while in late summer/fall of 2022 oxalic acid (32%) and Apivar® (29%) were the most common treatments used. The survey showed that 26% of small-scale beekeepers surveyed are not treating for varroa mites in the spring. This is concerning as spring is a very important time for beekeepers to control their varroa populations (by treating) so that they can prevent damage caused by varroa and the growth of varroa mite populations throughout the beekeeping season.

During the mid-season of 2022, a large proportion of commercial (47%) and small-scale beekeepers (62%) reported that they did not treat for varroa mites. Of the commercial and small-scale beekeepers who treated for varroa mites during the mid-season, the most common treatment method used by both groups was use of Formic Pro. The use of mid-season treatments has become an important part of the strategy to prevent varroa mite population growth and damage. This type and timing of treatment is likely a new concept for many beekeepers in Ontario, however, it is one that beekeepers will have to consider incorporating into their seasonal management to stay ahead of varroa mite growth.

The least commonly used treatments by both commercial and small-scale beekeepers were:

- CheckMite+™

- Bayvarol®

- ApiLifeVar

- Hopguard II

ApiLifeVar and Hopguard II are relatively newer treatments that have been registered for use in Canada.

These results are encouraging as it demonstrates that Ontario beekeepers are likely rotating their miticides, which is an important strategy for delaying the onset of resistant populations of varroa mites. However, there may be some cause for concern from the data as some responses supplied in the “other” response option indicated the use of treatments mid-season that may not be registered for use during a honey flow.

That being said, unregistered, mid-season treatments may have been used by beekeepers who had removed their honey supers or were managing their colonies whereby they were not producing honey (such as nucleus colonies or pollination units). Of note, the industry appears to be quite reliant on Apivar® as a control method for varroa mites. Should the Ontario industry see development of varroa mite resistance to amitraz (the active ingredient in Apivar®), it may seriously restrict beekeepers’ ability to control varroa mites, resulting in increased mortality of colonies in Ontario. While other chemical options are available many of them are temperature dependent (such as formic acid), which may factor in the timing and choice of treatment depending on the weather conditions during a particular season in Ontario.

As amitraz resistance has been documented in varroa mite populations in the United States, it is important to monitor its status in Canada. New compounds will be needed for varroa mite control to ensure there is a robust set of options available to beekeepers and to offer the opportunity to rotate treatments so that beekeepers can continue to incorporate effective integrated pest management practices in their beekeeping operation.

It should be noted that varroa mites in Ontario have established resistance (or reduced efficacy) to other compounds (for example, coumaphos, fluvalinate, flumethrin).

| Varroa mite treatment (active ingredient) | Spring 2022 % of commercial beekeepers | Spring 2022 % of small-scale beekeepers | Mid-season 2022 % of commercial beekeepers | Mid-season 2022 % of small-scale beekeepers | Late summer/fall 2022 % of commercial beekeepers | Late summer/fall 2022 % of small-scale beekeepers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apistan® (fluvalinate) | 7% | 3% | N/A | N/A | 7% | 6% |

| CheckMite+™ (coumaphos) | 0% | 0% | N/A | N/A | 0% | 0% |

| Apivar® (amitraz) | 39% | 24% | N/A | N/A | 50% | 29% |

| Thymovar (thymol) | 6% | 3% | N/A | N/A | 3% | 3% |

| ApiLifeVar (thymol and essential oils) | 0% | 0% | N/A | N/A | 0% | 0% |

| Bayvarol® (flumethrin) | 0% | 0% | N/A | N/A | 0% | 0% |

| 65% formic acid – 40 mL multiple application | 17% | 5% | N/A | N/A | 15% | 4% |

| 65% formic acid – 250 mL single application | 3% | 3% | N/A | N/A | 1% | 2% |

| Mite Away Quick Strips™ (formic acid) | 3% | 5% | 7% | 6% | 4% | 5% |

| Formic Pro (formic acid) | 17% | 22% | 33% | 21% | 24% | 17% |

| Oxalic Acid | 26% | 16% | N/A | N/A | 53% | 32% |

| Hopguard II (hop compounds) | 0% | 2% | 0% | 1% | 0% | 1% |

| Other | 6% | 2% | 10% | 6% | 6% | 2% |

| None | 14% | 26% | 47% | 62% | 0% | 14% |

Nosema spp. (N. apis and N. ceranae)

92% of commercial and 89% of small-scale survey respondents indicated that nosema treatment was not applied in the spring of 2022, while 89% of commercial and 79% of small-scale survey respondents did not treat for nosema in the fall of 2022 (Table 7). Nosema is a disease that has been identified to delay the development of honey bee colonies in spring and reduce the lifespan of individual honey bees, but has not been identified as a factor in colony mortality over winter

| Nosema treatment | Spring 2022 % of commercial beekeepers | Spring 2022 % of small-scale beekeepers | Fall 2022 % of commercial beekeepers | Fall 2022 % of small-scale beekeepers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fumagillin | 6% | 6% | 6% | 5% |

| Other | 3% | 1% | 0% | 1% |

| None | 92% | 89% | 89% | 79% |

American foulbrood (Paenibacillus larvae)

A little more than half of commercial beekeepers who responded to this survey question had treated for American foulbrood (AFB) during spring 2022 (58%) and during fall 2022 (54%) with oxytetracycline. By comparison, 19% of small-scale beekeepers reported treating for AFB in the spring and 17% treated for AFB in the fall (Table 8).

| American foulbrood treatment | Spring 2022 % of commercial beekeepers | Spring 2022 % of small-scale beekeepers | Fall 2022 % of commercial beekeepers | Fall 2022 % of small-scale beekeepers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxytetracycline | 58% | 19% | 54% | 17% |

| Tylosin | 0% | 0% | 1% | 0% |

| Lincomycin | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Other | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| None | 39% | 75% | 44% | 70% |

Ontario’s overwinter mortality

The Canadian Association of Professional Apiculturists compiles overwinter mortality data provided by each province and publishes an annual report on national honey bee colony losses. Figure 4 compares Ontario’s overwinter mortality levels to that of Canada’s. The 2023 estimate for commercial beekeepers in Ontario (35.7%) was approximately 3.5% more than the estimation for bee loss averaged between all of Canada (32.2%).

Accessible description for Figure 4

Accessible image descriptions

Figure 1. Type of varroa mite monitoring method used by commercial and small-scale beekeepers in 2022.

Figure 1 shows the type of varroa mite monitoring method used by commercial and small-scale beekeepers in 2022. 5% of commercial beekeepers reported using the sticky board method, 62% used the alcohol wash method, 9% used both sticky board and alcohol wash, 9% used other methods, and 14% reported no monitoring for varroa mites. 25% of small-scale beekeepers reported using the sticky board method, 26% used the alcohol wash method, 6% used both sticky board and alcohol wash, 11% used other methods, and 31% reported no monitoring for varroa mites.

Figure 2. Frequency of varroa mite monitoring by commercial and small-scale beekeepers in 2022.

Figure 2 shows the frequency of varroa mite monitoring by commercial and small-scale beekeepers in 2022. Commercial beekeepers – 50% at least 3 times a year, 19% both in spring and in fall, 7% just in the spring, 8% just in the fall, and 15% did not respond to this question. Small-scale beekeepers – 29% at least 3 times a year, 23% both in spring and in fall, 6% just in the spring, 13% just in the fall, and 29% did not respond to this question.

Figure 3. Frequency of varroa mite monitoring by commercial and small-scale beekeepers in 2022 who reported monitoring at least 3 times a year. Survey respondents could select more than one answer.

Figure 3 shows the frequency of varroa mite monitoring by commercial and small-scale beekeepers in 2022 who reported monitoring at least 3 times a year. Commercial beekeepers – 6% every 2 weeks, 58% every month, 31% less frequent than every month, 11% before and after each treatment, and 3% did not respond to this question. Small-scale beekeepers – 13% every 2 weeks, 45% every month, 32% less frequent than every month, 13% before and after each treatment, and 1% did not respond to this question.

Figure 4. Overwinter mortality (%) reported by commercial beekeepers in Ontario (blue) and Canada (grey) from 2006-2007 to 2022-2023.

Figure 4 shows the percentage of overwinter mortality reported by beekeepers in both Ontario and Canada from 2007 to 2023. The reported overwinter mortality in Ontario and Canada (respectively) was the following: 2007 – 37% and 29%; 2008 – 33% and 35%; 2009 – 31% and 34%; 2010 – 22% and 21%; 2011 – 43% and 29%; 2012 – 12% and 15%; 2013 – 38% and 29%; 2014 – 58% and 25%; 2015 – 38% and 16%; 2016 – 18% and 17%; 2017 – 27% and 25%; 2018 – 46% and 33%; 2019 – 23% and 26%; 2020 – 19% and 30%; 2021 – 18% and 23%; 2022 – 49% and 46%; 2023 – 36% and 32%.

Footnotes

- footnote[1] Back to paragraph Guzmán-Novoa, E., L. Eccles, Y. Calvete, J. McGowan, P. Kelly and A. Correa-Benítez (2010). Varroa destructor is the main culprit for the death and reduced populations of overwintered honey bee (Apis mellifera) colonies in Ontario, Canada. Apidologie 41(4): 443-450.

- footnote[2] Back to paragraph Emsen, B., E. Guzman-Novoa, M. M. Hamiduzzaman, L. Eccles, B. Lacey, R. A. Ruiz-Pérez and M. Nasr (2016). Higher prevalence and levels of Nosema ceranae than Nosema apis infections in Canadian honey bee colonies. Parasitol Res 115(1): 175-181.

- footnote[3] Back to paragraph Emsen, B., A. De la Mora, B. Lacey, L. Eccles, P. G. Kelly, C. A. Medina-Flores, T. Petukhova, N. Morfin and E. Guzman-Novoa (2020). Seasonality of Nosema ceranae infections and their relationship with honey bee populations, food stores, and survivorship in a North American region" Veterinary Sciences 7(3): 131.