2021 Provincial Apiarist report

2021 Season highlights

The Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs’ (OMAFRA) Apiary Program conducted regular and targeted inspections.

Approximately 35,000 honey bee colonies were shipped outside of Ontario for the pollination of blueberry and cranberry crops in eastern Canada.

Ontario beekeepers reported an overall overwinter honey bee mortality of 18% for the winter of 2020–2021. This was lower than the overwinter mortality reported in the previous year (19%).

Notable statistics about the 2021 Ontario beekeeping industry include:

- number of registered beekeepers: 3,227

- number of registered colonies: 102,328

- average honey yield/colony: 28 kg (63 lb) per colony

- total estimated honey crop: 2.9 million kg (6.4 million lb)

- overwinter honey bee losses reported by commercial beekeepers: 18%

Pest and disease levels

During the 2021 beekeeping season, OMAFRA inspected a total of 471 bee yards. The presence of common apiary pests and diseases was assessed by ministry apiary inspectors through the brood nest inspection of 5,440 colonies. Inspectors checked for varroa mites in 1,189 of the colonies receiving brood nest inspections and checked for small hive beetle in an additional 9,647 colonies through top bar inspections. The prevalence of the following diseases among inspected colonies were:

- American foulbrood: 0.48%

- European foulbrood: 0.59%

- sacbrood virus: 0.15%

The data represents the colonies inspected in 2021 and is not necessarily reflective of the beekeeping industry across the province.

American foulbrood (Paenibacillus larvae)

American foulbrood (AFB), a bacterial disease of honey bees, was detected in 26 honey bee colonies or 0.48% of the colonies inspected in Ontario. These colonies represented 11 bee yards positive for AFB or 2.14% of the yards inspected. The 2021 data represents an increase in AFB from 2020 when AFB was observed in 0.09% of colonies. While any increase in a disease as serious as AFB merits some attention it is not clear if this is the start of a larger trend as this represents a snapshot in time and the inspections were not randomly assigned. Furthermore, it should be recognized that apiary inspectors work with beekeepers to ensure that AFB-infected colonies are destroyed and the infection is controlled.

Sample analysis continues to confirm that the strains of AFB circulating in Ontario remain susceptible to oxytetracycline.

Small hive beetle (Aethina tumida)

Small hive beetle (SHB) is an insect pest of honey bees. A total of 49 apiaries, both commercial (operating 50 or more colonies) and small-scale (operating 49 or fewer colonies), tested positive for SHB in Ontario. This represents an increase in new detections in 2021 when compared to 2020 (n=38). Positive findings of SHB may be overrepresented in inspection results due to the high rate of inspection of colonies in the Niagara region to allow for the movement of colonies for out of province pollination. Colonies in this region make up a large proportion of apiary inspections.

The presence of larvae, which is the main cause of SHB damage to colonies, is documented during apiary inspections. Reports continue to demonstrate that there have been very few instances of SHB creating damage to colonies in the province and the impact of this pest in Ontario remains limited to date.

The ministry has an online map showing the number of SHB-positive bee yards confirmed in each township. This map not only provides current data to other jurisdictions that import Ontario honey bees, but also informs beekeepers about where SHB has been detected in Ontario, which helps them to manage the risk to their beekeeping activities.

Varroa mites (Varroa destructor)

Ministry apiary inspectors sampling for varroa mites, a common and very serious pest of honey bees, during regular apiary inspections typically documented low levels of infestation early in the beekeeping season for both commercial and small-scale beekeepers and extending into summer for many commercial beekeepers. Across the province, 1,189 (758 commercial, 431 small-scale) colonies were inspected for varroa mites using a standard alcohol wash (a sample of approximately 300 bees collected from the brood nest, washed in alcohol and the varroa mites filtered and quantified).

As varroa mites are widely distributed across the province, the prevalence of these mites is not as informative as the degree of infestation. Guzman et al. (2010) established treatment thresholds for varroa mite infestations. Colonies should be treated for varroa mites in:

- May if the infestation is greater than 2%

- August if the infestation is greater than 3%

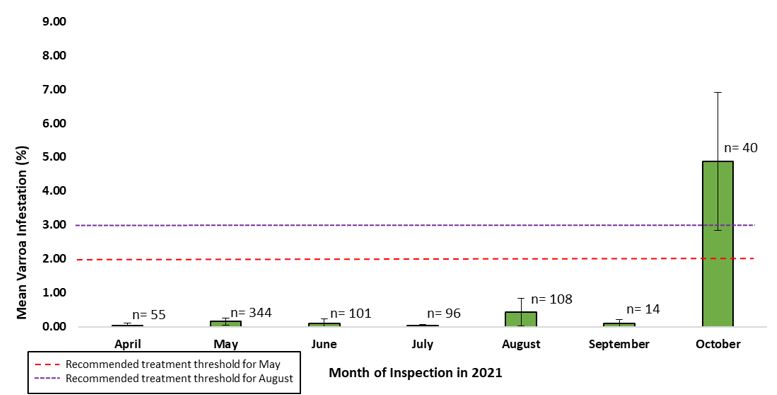

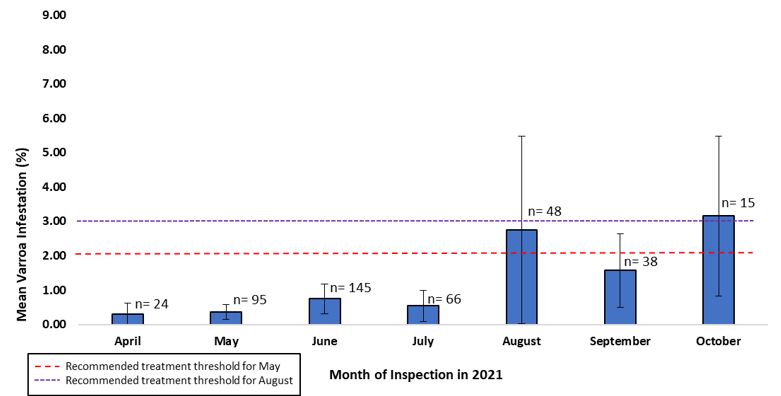

Among commercial operations, the mean varroa mite infestation remained below treatment thresholds and ranged from a low of 0.03% in July to a high of 4.88% in October (Figure 1). The degree of varroa mite infestation among small-scale operations was higher during the season (particularly from August to October) in comparison to commercial beekeepers and ranged from a low of 0.31% in April to a high of 3.16% in October (Figure 2).

While most of the colonies sampled (represented by mean) during inspection for varroa mites were below the treatment threshold in late summer and fall (3 varroa mites per 100 bees), there were colonies that were above the threshold. This demonstrates that colonies were likely heading into the winter with damaging levels of varroa mite infestation.

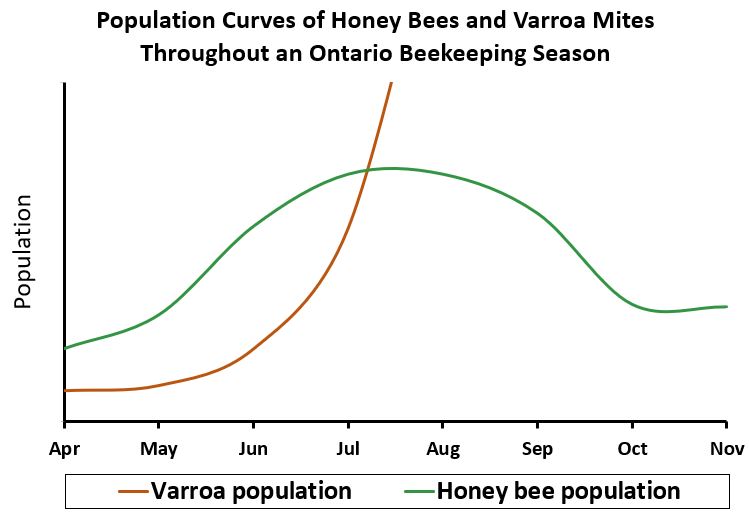

In the 2021 season, multiple commercial beekeeping operations reported colonies “crashing” (that is colonies with a large proportion of the bees in the colony abruptly dying) with “noticeably” high varroa mite levels in mid-to-late summer. This is particularly concerning as it is not typical for colonies to succumb to varroa mite damage this early in the season. Typically, colonies with high varroa mites will die during winter, or if truly severe, in the fall. Reports of this very early damage is an indication that varroa mite levels increased earlier than usual in the 2021 beekeeping season.

The life cycle of varroa mites is linked to and dependent on the life cycle of honey bees as varroa mites cannot reproduce independent of developing honey bees. If reproduction of honey bees takes place earlier in the season, then varroa mites are increasing their levels earlier and reaching peak populations earlier. As soon as honey bee brood is produced, varroa mites begin to reproduce and increase their population (Figure 3). Additionally, varroa mites have an exponential population growth whereby an increase in levels accelerates with progressive intensity. This is important to note because once varroa mites begin to reach a certain level they may become difficult to manage due to the sheer number present in the colony. The spring of 2021 began uncharacteristically early with many colonies in Ontario beginning to produce honey bee brood and build-up in population much earlier (3 to 4 weeks) than typical years. This is supported by the fact that beekeeping operations reported a large number of swarming events throughout Ontario, as swarming is an indication of accelerated colony development.

This underscores the importance of regularly monitoring for varroa mite levels throughout the beekeeping season as it can be easy to miss early population peaks, especially when growth falls outside of a typical years’ pattern. Furthermore, if beekeepers do not sample at numerous times throughout the season, to know definitively if their varroa mite levels are low, then it becomes very difficult to dismiss varroa mites as a major factor of overwinter colony loss. Ultimately, it is important for beekeepers to understand that weather and seasonal conditions have an influence on varroa mite levels and that they have to adapt their management practices accordingly, especially as earlier springs and warmer weather lasting longer into the fall are becoming more and more common with climate change.

Consistent with previous years, commercial beekeepers demonstrated a lower degree of infestation compared to small-scale beekeepers and this may confirm some success this group of beekeepers is having with the management of varroa mites. However, the fact that fewer colonies operated by both commercial and small-scale beekeepers were inspected in the fall and that sample sizes were small may have contributed to the observed increase in mean varroa mite infestation for beekeeping operations in the fall. As this data is gathered through inspections and as inspections are not random, high varroa mite infestations may be missed within the honey bee population. Both of these gaps in data collection could be considered for improvement in the future.

Overall, the available data demonstrates that both regular monitoring throughout the season and late season monitoring for varroa mites are important. In particular, late season sampling in September and in October, after varroa mite treatment has been applied, is important to ensure that the treatment used was effective at lowering the level of infestation and that reinfestation with varroa mites from nearby apiaries is not occurring.

One factor that may have impacted the management of colonies for some of the larger commercial beekeeping operations in 2021 was issues with accessing migrant labour in a timely manner due to the COVID‑19 pandemic. Large commercial beekeeping operations, like many other sectors of agriculture, rely on highly trained staff returning from other countries to carry out important field management within the beekeeping operation. While commercial beekeepers can do some of this on their own, a delay in the arrival of trained staff may result in some tasks, particularly management tasks, being delayed and completed at a later time when staff are available (for example, varroa treatments or sampling), thus impacting the longer-term survival of colonies.

Learn more about varroa mites.

Treatments for varroa mites

As part of a robust and sustainable integrated pest management strategy for varroa mites (and other pests and diseases) it is important that beekeepers have access to multiple types of treatments with different active ingredients. This allows for rotation of treatments with different active ingredients to delay the onset of pest resistance to such treatments and for use of formulations under different conditions (as timing and weather may vary). The Ontario Beekeepers’ Association is pursuing the registration for 2 new varroa mite treatments. The Canadian Association of Professional Apiculturists, OMAFRA, and the Canadian Honey Council are assisting in different parts of the registration process. The province has also highlighted this as a priority for the health and sustainability of honey bees.

Honey production

Honey survey questionnaires were mailed to registered Ontario commercial beekeepers to estimate the average honey production in the province. Responses were received from 28% of commercial beekeepers, representing approximately 13,000 colonies across the province.

Based on the responses, the estimated average honey production in Ontario was 28.4 kg (62.6 lb) per colony. This is a major decrease in honey production from 2020 (37.9 kg or 83.6 lb per colony) driven by weather unfavourable for nectar-producing conditions in many parts of Ontario.

Pollination services

Ontario honey bee colonies are sent to pollinate berry crops in eastern Canada (Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island). Approximately 35,000 honey bee colonies were moved from Ontario to eastern Canada in 2021 for the purpose of pollination. This number is down from the 39,231 honey bee colonies that left the province in 2020 for pollination services. This decrease in colony numbers may reflect the decrease in demand in pollination services required from the blueberry sector in eastern Canada as well as the decrease in available colonies managed by Ontario beekeepers who provide pollination services, as both may fluctuate from year to year.

As is now set practice, Ontario and the eastern Canadian provinces worked collaboratively to define pre-transportation inspection requirements before colonies were shipped across provincial borders. The spread of small hive beetle from regions in Ontario to eastern Canada remained a concern for inspection requirements in 2021.

Honey bee mortality

Overwinter honey bee mortality

During the spring of 2021, a survey was used to estimate overwinter honey bee colony losses. The survey was distributed to 252 registered commercial beekeepers. Responses were received from 36% of the commercial beekeepers surveyed representing 42,467 colonies across the province. Based on the results of the survey, commercial beekeepers reported an approximate 18% overall honey bee colony loss during the 2020–2021 winter. This was a decrease from the 19% winter loss reported in the previous year (2019–2020). Small-scale beekeepers reported a higher winter loss (37%) than that of the commercial sector.

See the full report on 2021 overwinter losses.

In-season honey bee mortality

A honey bee incident is defined as atypical effects characterized by bee mortality, or sub-lethal effects observed in a honey bee colony and suspected by a beekeeper to be related to pesticide exposure. OMAFRA’s Agriculture Information Contact Centre receives reports of honey bee incidents in Ontario. These are shared with the Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks (MECP) and Health Canada’s (HC) Pesticide Management Regulatory Agency (PMRA).

Upon review of the information provided for a reported incident, an inspection may be conducted of the reported yard(s) by either OMAFRA (for a honey bee health issue) or by MECP or HC (for a pesticide related issue). In 2021, OMAFRA received 10 in-season honey bee mortality incident reports.

Pesticides

Pesticides, under certain circumstances, can pose further challenges to honey bees and other pollinator populations. If a beekeeper suspects that their bees have been impacted by a pesticide during the regular beekeeping season it is important that the beekeeper report this in a timely manner to OMAFRA by contacting the Agricultural Information Contact Center (AICC) by phone at

Researchers are also actively looking into chronic and long-term pesticide exposure in honey bees. Honey bee colonies have been found with pesticides (insecticides, fungicides and herbicides). Whether these are at damaging levels or not needs to be determined by research, scientists and pesticide specialists.

Placement of honey bee colonies

In recent years, the 2021 beekeeping season being no exception, the Apiary Program has seen an increase in the number of complaints related to the placement of honey bee colonies. As directed by the Bees Act, colonies cannot be located or placed within:

- 30 m of a property line separating the land on which the hives are placed from land occupied by a dwelling or used for a community center, public park or other space used for public assembly or recreation

- 10 m of a highway

Given the rising interest in beekeeping in Ontario there are new beekeepers setting-up their hives in urban or suburban areas (backyard beekeeping). The Apiary Program expects landowners and beekeepers to be diligent in ensuring the Bees Act location requirements are met and encourages beekeepers to consider the appropriateness of the location and the risks to the public (for example, negative human-bee interactions such as stinging incidents, allergies and close proximity to neighbours) with the placement of colonies at any location. It should be noted that many beekeepers have sought out landowner permission to place their honey bee colonies on another person’s property after ensuring the location is suitable for honey bees (that is, an abundance of forage and a water source). These locations are most often in rural settings.