We've moved this content over from an older government website. We'll align this page with the ontario.ca style guide in future updates.

Focusing on middle childhood

The middle years refer to the period in life between early childhood and adolescence. Generally, child development experts consider children between the ages of 6–12 as being in their middle years.

The importance of the middle years

Today’s middle years children

Ontario is home to more than one million children ages 6–12. This number is expected to increase to 1.26 million in the next 20 years.

Middle years children in Ontario today are different from any generation before them. They are growing up in a dynamic time of rapid change. Technology plays an increasingly prominent role in children’s lives, and brings with it many new opportunities as well as challenges.

Ontario’s middle years children are very diverse, with 32% identified as being a visible minority and 45.5% identified as first or second generation Canadians.

A distinct and important stage of development

There is new and emerging research that sheds greater light on this important developmental stage. The middle years are now understood as a key developmental turning point that set the foundation for personal identity, lifelong skills, habits and values.

Middle childhood is a period when children are exploring who they are and who they want to be, establishing basic skills and health habits, grappling with puberty, physical changes and gender roles, making friendships and forming attitudes about the world they live in, and taking first steps toward independence. This is a time of challenge as well as opportunity for children and for the people caring for them. Families, extended families, and caring communities all play a central role in supporting children throughout the middle years.

The middle years are also a time when early indicators of mental health and behavioural and learning challenges become more visible, and when early interventions can make a significant impact on long-term outcomes. Parents, caregivers and other caring adults can support children during this critical window by providing them with the opportunities and resources to help them thrive, and by identifying "early warning signs" of mental health, behavioural, and learning challenges.

Bridging the early years and youth

On MY Way: A Guide to Support Middle Years Child Development bridges the existing early years and youth developmental frameworks. Resources for the early years include How Does Learning Happen? Ontario’s Pedagogy for the Early Years, which provides a resource to guide programming and pedagogy in early years programs; and Early Learning for Every Child Today, which includes a developmental continuum for children from infancy to school-age.

To support youth development, the Ontario government released Stepping Stones: A Resource on Youth Development to guide supports and services for young people between the ages of 12 and 25.

Together, these developmental frameworks form a continuum of resources to support optimal development and improve outcomes for children and youth from birth to age 25, along the life course.

How this resource was developed

Research on middle childhood development: Thirteen new research papers were developed by leading Canadian researchers to compile current evidence on middle childhood development.

Researcher think tank: A research forum was held with approximately 35 leading child development researchers on key topics related to health middle years development.

Discussions with families: Focus group discussions and one-on-one interviews were conducted with approximately 100 parents and caregivers to hear their stories and perspectives.

Middle years parent/caregiver experience survey:A survey asked more than 1,400 parents and caregivers about their experiences raising middle years children, including the challenges they face and the supports they receive.

Community workshops: A series of workshops across the province engaged 165 community partners and service providers to gain insights on supporting middle years child and family wellbeing.

Strategic roundtable: A roundtable was held with more than 60 provincial partners and stakeholders to discuss strategic priorities and outcomes for middle years children.

Premier’s Council on Youth Opportunities: The Premier’s Council on Youth Opportunities provided valuable insights on priorities, outcomes and opportunities to improve the wellbeing of all middle years children.

Indigenous partners: The provincial government worked closely with Indigenous partners through the Ontario Indigenous Children and Youth Strategy Technical Tables and through a review of Indigenous partners’ submissions for the Ontario Indigenous Children and Youth Strategy and changes to the Child and Youth Family Services Act to ensure that the perspectives of First Nations, Métis, Inuit and urban Indigenous partners were integrated into this resource.

A balanced and wholistic view of development

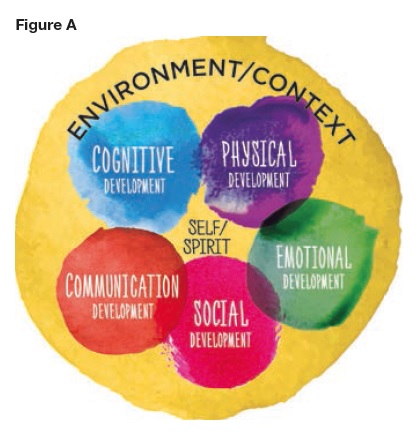

This resource provides an overview of the core skills, competencies and developmental milestones that children typically attain during middle childhood. Development can be seen through five domains (see Figure A):

Development is interdependent

Development does not occur along a straight line. We have identified five domains or areas of development — cognitive, emotional, social, physical, and communication — that are constantly at work influencing and building upon one another. Developmental domains are interdependent, and progress in one supports progress in others. Promoting optimal development involves encouragement and support to achieve balance and growth across all of these domains.

A way of looking at this is to consider how a child’s brain development may begin to enable them to recognize others, and become aware of others’ perspectives. This in turn, enables them to have more connected social interactions, and as a result further develop their social skills, as well as practice their growing communication skills.

Similarly, when a child experiences challenges across one developmental domain, this will impact other aspects of their development.

If this is the case, why do we break child development into different domains? The answer is that they are an entry point.

Thinking in terms of the different domains allows us to break down and understand all of the different changes that are taking place. This is useful in understanding developmental "events" or what is happening in children, their influences, and how we support optimal outcomes as children develop through their middle years.

Influences and context are key

Children in the middle years are seeking independence, exploring a dynamic and influential new world of friends, teachers, school staff, coaches and traditional knowledge keepers, and establishing new social identities in what is to them an increasingly broad community.

At the same time, middle years children are dependent on the care and support they receive at home, in their schools and in their communities. From giving children a sense of comfort and safety to guiding their emotional and cognitive development, parents and caregivers and other caring adults in the community have a very important role to play. The positive influence of caring adults on the development of children is an essential component of Ontario’s Middle Years Strategy.

The best way for children to grow and develop successfully is for all of the significant influencers in their lives to be working together to support them. This includes families and extended families, schools, after-school programs, service providers and other caring adults in the community.

Every child is unique and develops at their own pace

Children of all abilities and from all backgrounds develop physically, socially, emotionally and cognitively, and they all develop communication skills. However, the ways that children develop across these domains differs widely. Each child is unique and develops at their own pace. A child’s developmental journey occurs along a path shaped by their own experience, context, social and environmental factors.

Because of these differences, it is important to avoid the concept of "normal" development. No one developmental pathway can be generalized to include all children.

Valuing all children equally means respecting the diversity of their developmental journeys. This resource takes an inclusive view of child development, so that all children can see themselves reflected in it.

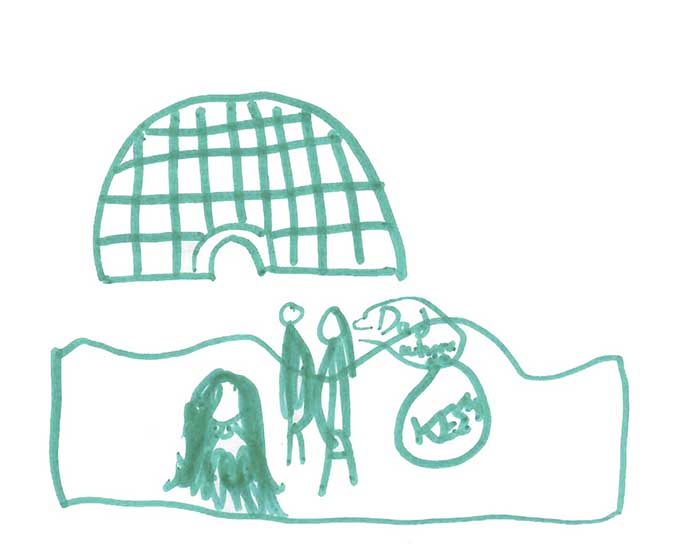

Families matter

Families and extended families play a critical role in supporting middle years child development. Children live in many different types of families, including those that are led by one parent, multiple parents, grandparent(s), foster parent(s) or other caregiver(s). Some families are large and extended, while others are small. Friends and neighbours may also be a part of the extended family support network. There is no single way to be a family. Every type of family can be a source of strength for middle years children.

Parents and caregivers are often a child’s best support and champion. The most effective supports for children are those that have the overall child and family wellbeing in mind. The Ontario government acknowledges that supporting our children means supporting families. Children don’t exist and grow in isolation. Parents and caregivers are the experts on their children.

However, parents and caregivers sometimes need help. While most families in Ontario are thriving, some face significant pressures and challenges. Poverty, intergenerational and colonial trauma, special needs, language barriers, settlement challenges, racism and discrimination are all factors that can affect the needs and resilience of parents and caregivers. Supporting families and creating the conditions for all families to thrive is the best way to support optimal child development and ensure a promising future for all Ontario children.

Respecting Indigenous perspectives on wellbeing

Indigenous people in Ontario include many First Nations, Inuit, Métis and urban Indigenous communities. There is a rich diversity within and across Indigenous cultures. This diversity extends to where Indigenous peoples live, the languages that they speak, each community’s system of governance, cultural traditions and practices (including child rearing practices and norms), and how services are accessed and delivered.

Indigenous families

When considering Indigenous perspectives on wellbeing and child development, it is important to understand the traumatic impact of colonization on Indigenous families and communities. Colonial trauma continues to impact the wellbeing of Indigenous families and communities to this day. The roots of this trauma stem from policies and practices that specifically sought to disrupt and destroy Indigenous cultural traditions, family and community structures and child rearing practices.

The residential school system forcibly removed children from nourishing, loving families and communities; placed them in institutions that prohibited them from practicing their cultural traditions and speaking their Indigenous languages; and left them vulnerable to violence, abuse and isolation.

Colonial policies have resulted in widespread intergenerational impacts, including the disruption of traditional Indigenous parenting styles.

Many Indigenous families in Ontario today are led by vulnerable parents facing a range of challenges. Twelve per cent of Indigenous families are headed by parents under the age of 25 years, and 27 per cent are headed by single mothers.

Despite these issues, the rich cultural knowledge systems and child rearing practices of Indigenous peoples are being widely practiced and transmitted by Indigenous families today.

Indigenous wellbeing

A common element across Indigenous cultures is an understanding that wellbeing is interdependent, and involves individual, family, extended family and community wellbeing.

The stages of life are celebrated as each person brings forward different gifts and has a role in contributing to the wellbeing of the whole community. The life cycle reflects the interdependency of individuals, families and communities and their responsibilities to each other.

Belonging within a family and community is one of the most important indicators of Indigenous wellbeing.

Cultural learning and development

It is crucial for the wellbeing of Indigenous children, families and communities to preserve the culture and identity of Indigenous children. Cultural learning and development of one’s self and spirit is a core developmental need for Indigenous children and cuts across all of the developmental domains. First Nations and Inuit youth have indicated that culture provides them with balance and healthy relationships.

Cultural structures and methods of cultural learning differ across and within First Nations, Métis and Inuit cultures. These examples of cultural structures highlight the range of opportunities to promote cultural learning for Indigenous middle years children.

Elders, Senators and traditional knowledge keepers and community leaders also play a key role in mentoring Indigenous young people, passing on traditional knowledge, and supporting children and youth to build confidence and a strong sense of self.

Examples of Cultural Structures

Transformed relationships

First Nations, Métis and Inuit families and communities are in the best position to define their own needs and identify the supports they require to help their children and families thrive. First Nations, Métis and Inuit services are best when they are designed and delivered by and for First Nations, Métis or Inuit communities.

The right to Indigenous self-determination must be respected by anyone seeking to support an Indigenous child. Each First Nations, Métis and Inuit community has a unique cultural, social, historical and political context. Perspectives or cultural traditions should never be generalized across all First Nations, Métis and Inuit groups. Service providers should make contact and work in partnership with the relevant Indigenous organizations and communities, particularly when they are considering providing support and services to Indigenous children and families.

Working toward reconciliation and transformed relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous families, communities and partners is a shared responsibility. The middle years provide a rich opportunity to reinforce, teach and support all children— including those who are Indigenous and those who are not—to participate as knowledgeable, respectful and active partners in reconciliation.

Middle childhood is a crucial period to support identity formation, cultural learning and spirit development. For Indigenous middle years children and their families and communities, this period presents an important opportunity to reinforce a strong foundation in family and community, and a lifelong connection to self, spirit and culture, which cuts across all domains of development and equips Indigenous children to thrive.

Footnotes

- footnote[1] Back to paragraph Ontario Ministry of Finance. (2017). Ontario Population Projections Update, 2016-2041. Ontario, Canada: Ministry of Finance. Retrieved from http://www.fin.gov.on.ca/en/economy/demographics/projections/projections2016-2041.pdf.

- footnote[2] Back to paragraph Statistics Canada. (2013). Canada (Code 01) (table). National Household Survey (NHS) Profile. 2011 National Household Survey. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 99-004-XWE. Ottawa.

- footnote[3] Back to paragraph Métis Nation of Ontario, Ontario Federation of Indigenous Friendship Centres, Ontario Native Women’s Association. (2014). A Collaborative Submission Regarding a Provincial Aboriginal Children and Youth Strategy. Ontario, Canada: Metis Nation of Ontario, Ontario Federation of Indigenous Friendship Centres, Ontario Native Women’s Association. Retrieved from http://ofifc.org/sites/default/files/contentfiles/ACYS-Submission%202014-09-17.pdf.

- footnote[4] Back to paragraph Muir, N. & Bohr, Y. (2014). Contemporary practice of traditional Aboriginal child rearing: A review. First Peoples Child and Family Review, 9(1), 66–79.

- footnote[5] Back to paragraph Métis Nation of Ontario, Ontario Federation of Indigenous Friendship Centres, Ontario Native Women’s Association. (2014). Submission to Ontario’s Minister of Children and Youth Services Regarding a Provincial Aboriginal Children and Youth Strategy. Ontario, Canada.

- footnote[6] Back to paragraph Ontario Coalition of Aboriginal People, (2014)(OCAP). OCAP Summary Note on Ministry of Children and Youth (MCYS) Strategy Engagement. Ontario, Canada.

- footnote[7] Back to paragraph Muir, N. & Bohr, Y. (2014). "Contemporary practice of traditional Aboriginal child rearing: A review." First Peoples Child and Family Review 9(1), 66–79.

- footnote[8] Back to paragraph Simard, E. (2017). Indigenous Wellbeing in the "Middle Years": A Thematic Outline. Ontario, Canada: Institute for Culturally Restorative Practices.

- footnote[9] Back to paragraph Simard, E. (2017). Indigenous Wellbeing in the "Middle Years": A Thematic Outline. Ontario, Canada: Institute for Culturally Restorative Practices.

- footnote[10] Back to paragraph Healey, G. K., Noah, J., & Mearns, C. (2016). The Eight Ujarait (Rocks) Model: Supporting Inuit Adolescent Mental Health With an Intervention Model Based on Inuit Ways of Knowing. International Journal of Indigenous Health, 11(1), 92-110.

- footnote[11] Back to paragraph Ontario Native Women’s Association; Ontario Federation of Indigenous Friendship Centres. (2017). Definitions of Indigenous Health and Wellbeing. Ontario, Canada: Ontario Native Women’s Association.

- footnote[12] Back to paragraph Métis Nation of Ontario, Ontario Federation of Indigenous Friendship Centres, Ontario Native Women’s Association. (2014). A Collaborative Submission Regarding a Provincial Aboriginal Children and Youth Strategy. Ontario, Canada: Metis Nation of Ontario, Ontario Federation of Indigenous Friendship Centres, Ontario Native Women’s Association. Retrieved from http://ofifc.org/sites/default/files/content-files/ACYS-Submission%202014-09-17.pdf.

- footnote[13] Back to paragraph Chiefs of Ontario and the Ontario First Nations Young Peoples Council. (2014) Submission for the Child and Family Services Act, Review 2014/15 and Aboriginal Children and Youth Strategy. Ontario, Canada: Chiefs of Ontario.

- footnote[14] Back to paragraph Blanchet-Cohen, N., & Elliot, E. (2011). Young Children and Educators Engagement and Learning Outdoors: A Basis for Rights-Based Programming. Early Education & Development, 22(5), 757-777.

- footnote[15] Back to paragraph Métis Nation of Ontario, Ontario Federation of Indigenous Friendship Centres, Ontario Native Women’s Association. (2014). A Collaborative Submission Regarding a Provincial Aboriginal Children and Youth Strategy. Ontario, Canada: Metis Nation of Ontario, Ontario Federation of Indigenous Friendship Centres, Ontario Native Women’s Association. Retrieved from http://ofifc.org/sites/default/files/content-files/ACYS-Submission%202014-09-17.pdf.

- footnote[16] Back to paragraph United Nations. (2008). United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. New York: United Nations Economic and Social Council. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/DRIPS_en.pdf.

- footnote[17] Back to paragraph Simard, E. (2017). Indigenous Wellbeing in the "Middle Years": A Thematic Outline. Ontario, Canada: Institute for Culturally Restorative Practices.