4. Concept of operations

4.1. Overview

A concept of operations is a component of an emergency plan that clarifies the overall approach to responding to an emergency. This concept of operations describes the conceptual approach to provincial-level coordination in an emergency.

It forms the basis for the organization and activities described in Sections 5 and 6.

4.2. The graduated approach to emergency response

4.2.1. Individuals, families and organizations

The most basic level of response and recovery consists of individuals, families, and organizations dealing with an emergency that directly affects them. Impacted people and organizations may or may not need emergency support from the government, depending on the scale and nature of the emergency, and the resilience of those impacted (see section 3.5 for more information on resilience).

Individuals, families, and organizations that are impacted by an emergency lead their own response and recovery efforts, and they connect with government services on an as-needed basis. Individuals, families, and organizations impacted by emergencies do not have specific responsibilities under the Provincial Emergency Response Plan (PERP).

4.2.2. Multi-jurisdictional response

Individuals and organizations that are impacted by an emergency initiate their own emergency response actions where they are able to, focused on their own needs and responsibilities.

Formal government coordination of response and recovery efforts begins with the government with primary jurisdiction.

For many emergencies that occur in Ontario, there are overlapping jurisdictions, including community and political boundaries as well as layers of legislated responsibility or authority. Services from many levels of government could respond simultaneously to an emergency, each with jurisdiction for different responsibilities and aspects of the event. In addition, specific Ontario ministries have legislated emergency management responsibilities to make plans with respect to a type of emergency (see the OIC 1157/2009 that assigns these responsibilities in Appendix C).

An example of how all these different organizations come together during the response is a spill of a chemical from an industrial facility to the environment, which includes but is not limited to the organizations listed in Table 4-1.

Table 4-1: Example - organizations responding to an industrial chemical spill

| Organization | Level of response | Role |

|---|---|---|

|

Owner of chemical |

Individual/ Organization |

Report spill, initiate response efforts, trigger insurance claim. |

|

Fire and rescue, hazardous materials (HazMat) teams, police, and paramedic services |

Municipal government |

Life-safety response, containment. |

|

Hospitals |

Local Health System |

Treating injuries. |

|

Municipal Emergency Operations Centres |

Municipal government |

Coordination of municipal response activities. |

|

Public health units |

Municipal government |

Assess impacts to local population health and making recommendations. |

|

Reception centre |

Municipal government |

Emergency social services supports |

|

Spills Action Centre (Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks) |

Provincial government |

Assess environmental and health impacts, monitor and ensure response proceeds per legislative responsibility. |

|

Ontario Provincial Police, Ministry of Transportation |

Provincial government |

Emergency highway traffic control measures. |

|

Environment and Climate Change Canada |

Federal government |

Assess remediation and, if necessary, require that additional actions under applicable legislation. |

|

Ministry of Labour |

Provincial Government |

Worker safety. |

4.2.3. Capacity thresholds

It is possible that the needs of the responding organization(s) will exceed their capacity to effectively respond to some or all impacts of an emergency. This does not necessarily mean that these organizations have become overwhelmed, but that coordination efforts and resources must grow to appropriately respond to or recover from an emergency.

Existing additional arrangements can enhance response efforts, including but not limited to contractual agreements for specific services, bi-lateral agreements, and mutual assistance agreements with neighboring municipalities and/or upper tier municipalities, if applicable. At the provincial level, Ontario has made arrangements with neighbouring provinces and states for mutual assistance (refer to section 6.7.3.1 for details on provincial-level agreements).

If the emergency exceeds part or all of the capacity of an organization to respond, it can request support from the next level of government, as needed. For example, the Government of Ontario could request assistance from the Government of Canada to address gaps resulting from a provincial capacity being exceeded. The identified gaps could be addressed with any number of federal assets including, for example, the Canadian Coast Guard, Transport Canada, or the Canadian Armed Forces.

4.2.4. Large and widespread emergencies

In extraordinary circumstances, emergencies can occur where wide areas, large numbers of people, or significant critical infrastructure systems are affected. The impacts of large and widespread emergencies can vary significantly, depending on the resilience of the affected organizations and communities. In cases where these impacts are significant, normal service and resource arrangements may not be sufficient to meet the needs for response and recovery.

Coordinating organizations may need to prioritize the use of limited resources in large and widespread emergencies. The availability of staff and resources may be stretched to the point that organizations with continuity of operations plans may need to activate them to ensure that they may continue to respond to the emergency (see section 6.16 for more details on continuity of operations).

4.2.5. Requesting assistance

When one or more organizations have reached the limit of their response capabilities, or when an event happens that requires a capability that the organization does not have, extra assistance is needed. Requests for assistance are frequently consolidated through dedicated emergency management organizations.

There may be instances where emergency resources or coordination are provided to other jurisdictions though a mutual assistance agreement, federal request for assistance or other mechanism (this is separate from non-emergency foreign aid, which is a federal responsibility).

Individual ministries may provide assistance to other regions outside the scope of the PERP, through their own arrangements and agreements. The PERP may be used in the event that further coordination between provincial organizations is required. The PERP guides the actions of the provincial emergency response organization (provincial ERO) where such assistance is given as part of a coordinated provincial response, even if it is provided outside of the geographic limits of the province.

Example: A severe train derailment that leads to a large spill of a dangerous chemical (e.g., chlorine) into a community. That community's HazMat capacity is exceeded, and so the community's emergency operations centre makes a request to the province through the Provincial Emergency Operations Centre (PEOC) to deploy a provincial HazMat team. Other provincial ministries also become involved according to their jurisdiction, for example, the Ministry of Environment, Conservation and Parks would assist with drinking water issues and with air monitoring support.

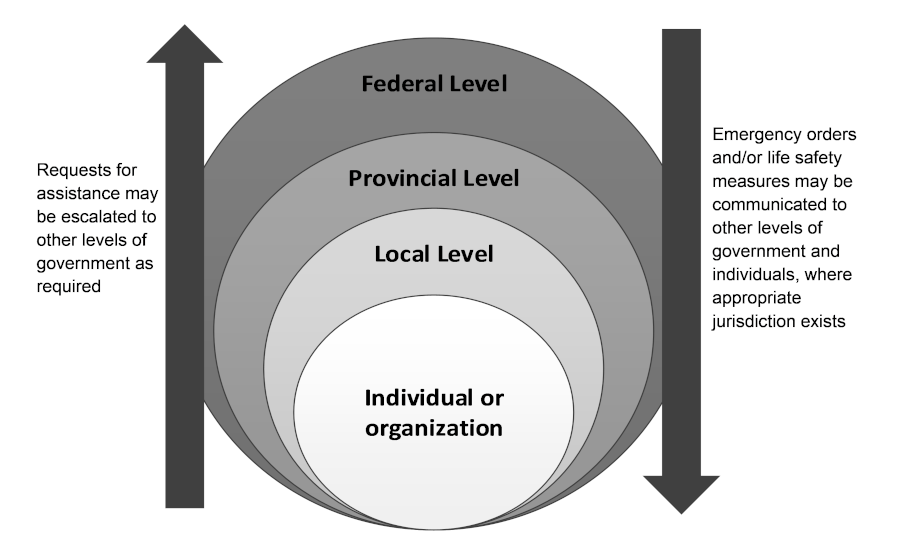

4.2.6. Graduated approach

The requests for assistance between levels of government generally follow a structure from the "bottom-up": from community, to provincial, to federal levels of government. All levels of this hierarchy work on different types of tasks and activities, with many jurisdictions and organizations working together in partnership through emergency management structures.

The "bottom-up" approach does not necessarily mean that emergency management must begin at the local level. Rather, it references the fact that efforts are often coordinated starting at the local level of government, and proceeding to the provincial and then the national level as more coordination of provincial and national resources are needed.

There are some exceptions to this rule. This includes requests for assistance under the Joint Emergency Management Steering Committee (JEMS) Service Level Evacuation Standards, where requests for assistance can pass from a First Nation to the PEOC and Indigenous Services Canada simultaneously, and response follows a consensus-based model. Similarly, a "top-down" approach might be found in incidents with specific provincial or federal government authorities, or where the provincial / federal governments need to request help from a municipality or province respectively.

Example: In a communicable disease outbreak similar to the 2003 SARS outbreak, the province through the Chief Medical Officer of Health could issue directives under the Health Protection and Promotion Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. H.7, to any health care provider or health care entity respecting precautions and procedures to be followed to protect the health of persons anywhere in Ontario.

In all cases where there is a need for coordination between provincial organizations, the provincial ERO facilitates Ontario's efforts in response, and helps coordinate between and across these different layers of government involvement.

4.3. Coordination

Coordination is a process designed to ensure that different and complex activities can work together effectively.

In the context of a response under the PERP, coordination encompasses three key components:

- Establishing a common understanding of roles and responsibilities as they relate to a particular response.

- Facilitating the activities of all relevant stakeholders to work towards common or complementary objectives.

- Sharing information in a timely and structured manner so that all stakeholders have a common understanding of the situation.

Most government organizations have a coordination centre to ensure that emergency response activities are effectively managed within its jurisdiction. In Ontario, all municipalities and ministries have emergency operations centres. The federal government employs a system of coordination centres and regional offices. More details on coordination centres for different levels of government can be found in section 5.

4.3.1. Community coordination

As an emergency grows in severity, and community resources become committed to response efforts, a dedicated coordinating organization is activated:

- In Ontario municipalities, a municipal emergency operations centre is activated, led by the Municipal Emergency Control Group (MECG)

footnote 11 . - On First Nation reserves, the coordination mechanism can vary, but is generally led by a combination of the fire chief and/or a dedicated emergency coordinator, under the direction of the Chief and Council.

Through its coordinating organization, the community manages its own resources to respond to and recover from emergencies. The community also coordinates with individuals, businesses and organizations, such as volunteers, non-governmental organizations, contractors, suppliers, and critical infrastructure owners.

Communities may rely on mutual aid agreements with adjacent communities to augment their emergency response.

There is no formal mechanism for emergency coordination for unincorporated communities under the Emergency Management and Civil Protection Act (EMCPA). In some cases, provincial staff may need to be deployed to assist unincorporated communities with the coordination of provincial emergency response activities.

4.3.2. Provincial coordination

There are potentially dozens of organizations involved in a response at the provincial level. While each individual organization works to coordinate its own response with that of its stakeholders, the number of ongoing activities in a widespread emergency requires a central hub to coordinate the overall response.

The PEOC is this central hub for provincial emergency response coordination. The PEOC coordinates overall response efforts between provincial organizations. The PEOC coordinates with organizations that are not part of the provincial government, including affected communities, the Government of Canada, neighbouring jurisdictions, private industry and non-governmental organizations. The specific mechanisms for this coordination are described in further detail in Section 6.8.

Ministries and other provincial organizations involved in a response may activate their own EOCs in order to coordinate their own response efforts.

Although the PEOC performs a coordination role for communications, it does not take control of every line of communication. The ministries and other provincial organizations should still communicate directly with other organizations in order to carry out their response activities.

The PEOC, actively involved ministries, and other involved provincial organizations together comprise the overall provincial ERO.

4.3.3. Federal coordination

The Government Operations Centre serves as the coordination centre for the federal response, providing regular situation reports as well as briefing and decision-making support materials for Ministers and Senior Officials.

Federal government institution-specific operations centres support their institutional roles and mandates and contribute to the integrated Government of Canada response through the Government Operations Centre.

When an emergency requires an integrated Government of Canada response, the Public Safety Canada Regional Director coordinates the response on behalf of federal government institutions in the region.

The Federal Coordination Centre, stood up by the Public Safety Canada Regional Office, coordinates the federal response during an emergency and the national Emergency Response System forms the basis for that coordination. The Federal Coordination Centre also becomes the single point of contact for the PEOC during a major response within Ontario.

4.4. Information management

4.4.1. Information management principles

Information management is a set of processes that directs and supports the coordination and use of information in an organization. It includes efforts to:

- Standardize terminology.

- Create credible and reliable information products.

- Perform analysis to inform decision-making.

Information management practices help improve situational awareness across responding organizations, and directly support emergency public information activities.

The information management process used by the provincial ERO facilitates effective decision-making and allows for a common and shared understanding of the:

- Status of the incident.

- Status of incident response and recovery activities.

- Status of resources.

- Plan of action.

Information management applies to, but is not limited to, the following types of data and communications:

- Telecommunications (voice and data).

- Geospatial Information Systems (GIS).

- Reports and other written products.

- In-person meetings and interactions.

4.4.2. Information management process

There are four phases in the information management process, which support effective and efficient coordination and use of information (see Figure 4-2).

During emergency response operations, the provincial ERO should move through this process at least once every operational period.

- Collect

- Identifying information requirements, including intended audience.

- Identifying sources of information.

- Gathering of information from all available sources.

- Organizing and storing information in a central, accessible place.

- Confirm

- Checking the accuracy of collected information, including evaluation of source trustworthiness, and verification against secondary sources. Where inaccurate or misinformation is identified, it should be flagged to the source to be corrected.

- Analyse

- Determining what information is important for the current operation.

- Determining who needs what information.

- Sorting out unimportant details.

- Identify any remaining information gaps.

- Organizing the relevant information to make it easy to understand.

- Creating information products (reports, maps, etc.) that can be used by responders and decision makers.

- Share

- Distributing information and analysis to the people and organizations who need it in an appropriate format and in a timely manner.

4.4.3. Emergency public information

Information management should include consideration for managing emergency public information.

The public needs up-to-date and accurate emergency public information through a variety of communications methods, including social and traditional media. In complex incidents several organizations may work together to coordinate their messages or may work together in a Joint Information Centre – refer to section 6.15.

4.4.4. Recordkeeping

All organizations involved in emergency response should make every reasonable effort to make accurate records of all emergency response activities. This includes proper filing and storage of all incoming and outgoing communications, information products, the completion of personal logs.

Having these records helps inform post-emergency reviews. Recordkeeping is critical in ensuring that best practices are captured, and mistakes are not repeated.

In addition to this general guidance, provincial organizations are subject to the Archives and Record Keeping Act S.O. 2006, Chapter 34, and the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act R.S.O. 1990, Chapter F.31. Specific organizations may be subject to other recordkeeping requirements under other legislation (e.g., the Personal Health Information Protection Act, S.O. 2004 Chapter 3). Operational record keeping procedures should be developed in consultation with legal counsel.

Refer to section 6.9.3 for details on protection of information.

4.5. Priorities

The PERP provides standardized response goals for the prioritization of response actions. The standardized response goals should be used to help guide all decisions made by the Government of Ontario in the response to any emergency. While the standardized response goals are intended to provide guidance on prioritization, they can and should be pursued concurrently where sufficient resources exist.

The standardized response goals are as follows, presented in descending order, and include examples of key actions for each (not an exhaustive list):

- Protect the safety of all responders

- Provision for physical and mental health.

- Protect and preserve life

- Provision of urgent emergency needs including rescue and emergency medical triage and care, issuing of information and warnings.

- Treat the sick and injured

- Medical care to those affected.

- Trauma management and mental health crisis intervention.

- Care for immediate needs

- Provision of immediate emergency needs, food, shelter, and clothing.

- Provision of immediate emergency needs of affected pets and livestock.

- Protection of community member's safety (including visitors and tourists).

- Protect public health

- Protection of community members' continuing health.

- Ensure the continuity of essential services & government

- Protection of critical infrastructure and community assets that are essential to the health, safety, and welfare of people, and that support community resilience.

- Protect property

- Protection of property from imminent threats.

- Protection of residential property as a place of primary residence.

- Protect the environment

- Protection of the environment from imminent threats.

- Prevent or reduce economic and social losses

- Reduction of economic and social losses.

4.6. Equitable service

Emergencies vary in intensity and complexity. Prioritization of actions is partly determined by the characteristics of the affected population(s) or assets, which are inconsistent across Ontario.

Ontario consists of diverse communities and groups. There are groups in Ontario that require special consideration from the provincial government in emergency response and recovery. These include patients in hospitals or long-term care, crown wards, inmates, persons with disabilities or other barriers to access services, and those who are otherwise more vulnerable than the rest of the population.

All response under the PERP should consider barriers to access services and the potential vulnerability of those affected by emergencies, to facilitate response with equitable outcomes. This includes work to identify equity-related issues and create approaches to address gaps.

4.7. Declaration of an emergency

Declared emergencies are a formal mechanism under the EMCPA that permits heads of government to take actions and make orders to protect the health, safety and welfare of the people, and to protect property and the environment in the emergency area. Similarly, the federal government can declare an emergency

First Nations can declare emergencies that triggers the implementation of the federal/provincial bilateral agreement for emergency response.

Unincorporated communities do not have the ability to declare emergencies, because no person or entity within an unorganized territory has the authority to declare an emergency under the municipal declarations provision of the EMCPA (4.). A provincial declaration of emergency can still be made by the Premier or Lieutenant Governor in Council to cover an unorganized territory. Refer to Section 6.6.5 for guidance on provincial declarations of emergency covering unorganized territories.

A declaration of emergency is not typically required in order to implement an emergency plan. Similarly, requests for assistance can be made with or without a formal declaration, by issuing a request to the next level of government. Provincial declarations of emergency are made when extraordinary legal powers are required. See section 6.6 for more details on declarations of emergency, and Appendix D for specific criteria for a provincial declaration of emergency.

4.8. Improvement planning

The improvement planning process is an aspect of quality management that aims to evaluate tasks or processes after they have been used and identify areas for improvement.

After action reports consist of analysis of actions undertaken during the response phase, inclusive of any activities or agency within the emergency response organization.

Ontario uses the improvement planning process as a key mechanism to link response and recovery to prevention, mitigation, and preparedness. After action reports and improvement plans identify and then address important gaps in prevention, mitigation, and preparedness.

Figure description

Figure 4-1: The graduated approach to emergency management

Requests for assistance may be escalated "upward" to other levels of government as necessary. This generally proceeds from an affected individual or organization, to the local government, then the provincial government, and finally the federal government.

Emergency orders and life safety measures may be communicated "downward" to other levels of government and individuals. This occurs where the “higher” level of government has a clear jurisdiction.

Footnotes

- footnote[11] Back to paragraph Some MECGs adopt a different name, particularly in two-tiered municipalities, to help distinguish them from each other. They are still performing the role of the MECG as required by O. Reg. 380/04.

- footnote[12] Back to paragraph There are four types of emergencies under the Emergencies Act: public welfare emergency, public order emergency, international emergency, and war emergency. Refer to the Emergencies Act for further details.