Part one: The foundations for our review and recommendations

A. Understanding the current realities of provincial custody in Ontario

For most Ontarians, the images we have formed about incarceration have likely derived from popular media, movies, television and books. Such depictions typically feature stories of hardened criminals serving lengthy sentences, many for unspeakable crimes. Some settle on themes of fear and conflict. Some manage to convey a sort of closed community, highlighting the long-term camaraderie among prisoners, and between prisoners and their familiar guards. Others might showcase institutional efforts to provide meaningful work programs, to support the development of new skills, to restore spiritual and emotional well-being, and to sustain hopes for a smooth transition to independent and crime-free lives.

The situation in our provincial correctional facilities is an entirely different reality. To begin with, the majority of residents have not been convicted of the crime or offense for which they are being held. Only about a quarter of the population on any given day may already be serving a court-determined sentence ranging from a few days to two years less a day, or they may ultimately be convicted of the crimes and provincial offences that brought them into custody. Many will not. Many will be in custody for less than a month.

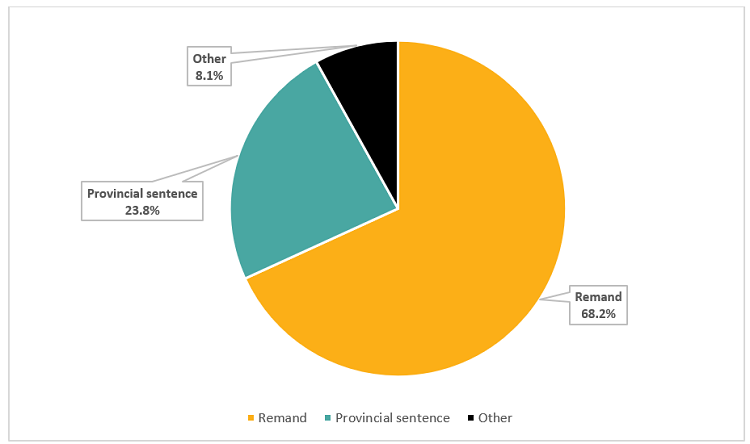

Figure 1 presents the percent of all persons-in-custody in Ontario, broken down by their hold status (see Glossary for definitions). The percentages presented are based on average daily counts and are presented for the combined period 2014 through 2021. Individuals on remand make up the largest proportion of the population (68.2%).

Almost all of them across Ontario will be held in maximum security. While in custody, they most commonly will be referred to as offenders.

There is no single prototype by which these individuals might be more accurately described. In this report, we have chosen to avoid the offender label. The residents can alternately be called persons-in-custody, but to be clear, for the duration of their stay, they are prisoners of the state. Their needs and their life experiences are complex and diverse. Many have ongoing substance use disorders. Many have been periodically or chronically unhoused or living in unstable circumstances. Many have suspected and/or diagnosed mental health conditions. Many have been victims of crime, abuse and trauma. Some have done terrible things. Some have exhibited erratic or unpleasant behaviours deemed to be a threat to public safety. Some have merely nowhere else to go. For the most part, all of them will be housed together, but some will spend long periods in isolation if they are deemed to be at risk from others, a threat to others, a threat to themselves, or at their own request.

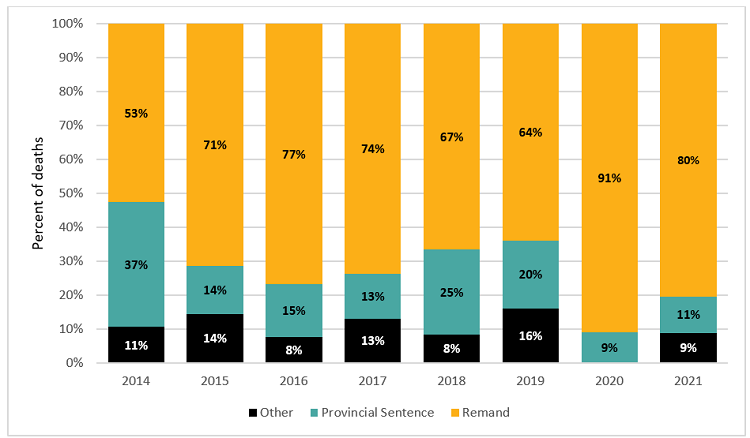

Figure 2 presents the proportion of deaths by hold status. In each year, individuals on remand made up the largest proportion of deaths among persons-in-custody, with the highest proportion in 2020 (91%).

Our panel learned that the catchphrase that is meant to define the duties and responsibilities for most of the staff is care, custody and control. By necessity, for the safety of everyone involved, it is control that will mostly define the in-custody experience. Under the current patterns of remand in the Ontario courts, it is care that most of these persons-in-custody require. Under current conditions in Ontario’s facilities, we learned that it is care that remains the most elusive, despite the commitment, skills and best efforts of those who are meant to provide it.

We also learned that the dominant term that underpins this sad reality is the term lockdown.In those popular prison images we have come to know, lockdowns are usually depicted as an emergency response to unruly behaviour. Only a very small fraction of Ontario’s lockdowns are triggered by such events. The vast majority of lockdowns are initiated in response to inadequate staffing. In recent years, the frequency of such events is alarming. The negative consequences are wide ranging for persons-in-custody and their families, and also for correctional officers, health care providers and the essential spiritual, cultural and community supports that are meant to bring care into the custody equation.

In Part two of this report, we will expand on these conditions and others as we outline actionable factors leading to the prevention of deaths and a safer and healthier environment in Ontario’s custodial facilities. But we would be remiss if we did not first point out a fundamental misalignment that should be a critical concern to everyone in Ontario.

As it stands, our human services system has all but defaulted to the criminal justice system as the primary path of choice to address persons with complex needs. More specifically, when such individuals act out, or merely present in a manner that is deemed anti-social, disruptive to the public peace, or merely unpleasant to encounter, we expect the police to intervene for everybody’s immediate safety. Too often, when other options do not exist, or may exist but in such limited capacity to be of no immediate assistance, the individual is charged and taken to court to answer for their offending behaviour, or in some effort to curtail that behaviour, or simply to remove their offending presence from the community. Very often, it is the same complexity of their needs that renders these individuals ineligible for immediate bail release conditions, and as result, an ever-increasing number are remanded into provincial custody. Many will be released back into the community within a few days, some a bit longer. But, as precluded by the current conditions in our facilities, most will depart with few supports provided in the interim that might have improved their ability to resume healthier and safer lives in the community. Many will return, again and again.

For more than two decades, remand has accounted for all growth in provincial custody numbers, and now represents almost 70% of the in-custody population. The dominant profile of the population has become one of complex needs that require health care, mental health care, addictions treatment and recovery, and transition supports that can facilitate continuity of care and success at living in the community. Almost none of these things can be provided to the required degree in any of our prisons, and most certainly not in a prison where lockdowns due to capacity limitations have become the norm.

It is beyond the scope of our review to resolve such systemic challenges. However, we would offer to those who can, to consider this question. If we are to continue using the criminal justice system to manage people in this manner, is it not incumbent on us all to at least do it well? Or, perhaps more to the point, if all evidence says we cannot do this well, we cannot do it economically and we cannot do this safely, then perhaps the entire system needs to stop thinking we can.

The increasing adoption across Ontario of collaborative models for community safety and well-being represent significant promise for alternative solutions. Such models routinely bring together both the available data and the qualified professionals from health, mental health, addictions support, housing, education, social services, community-based organizations and police working in a more supportive rather than enforcement manner. Under the demonstrated promise of such models, more individuals can be helped in the community and more equitable services can be made accessible and more effective. At the same time, collaborative and proactive solutions can also reduce risks to public and personal safety, clear backlogs in the courts and ultimately, achieve lasting reductions in the temporary custody arrangements that have grown to unmanageable levels in Ontario’s prisons. We know that many practitioners in each of these sectors have embraced these opportunities to do things better. We encourage senior policy makers to continue to amplify the importance of these forms of systemic reform.

Within the scope of this review and in this report, our panel will address itself to how corrections officials at all levels can save lives and promote health, well-being and greater humanity to Ontario’s correctional facilities, for the benefit of those in custody, and also for the deserving professionals charged with their care, custody and control.

B. Understanding the deaths in provincial custody 2014–2021

This review was initiated in January 2022 by the Chief Coroner for Ontario, Dr. Dirk Huyer. Among the triggering factors was, of course, two years of the COVID‑19 pandemic, and questions about how this may have contributed to in-custody deaths. At the same time, an initial analysis showed that the increasing pattern in death rates was already evident in the years before the pandemic struck, and very few of the deaths in 2020 and 2021 had any directly evident connection to the illness. Between January and September, the Correctional Services Death Review (CSDR) team framed out the study to span from 2014 to 2021, and they set out to source the necessary data that might provide insights into any patterns and evident contributing factors. This turned out to be a very difficult task, and that fact alone forms some of our findings and recommendations in Part two and Part three.

It is important to note that coroners across the province have already pronounced on the cause and manner of death in almost all cases in our sample. This review applies a collective lens and seeks answers to one very important question that remains. Why were these deaths not prevented?

Our diverse, nine-member Expert Panel was formed by late September, and we benefitted considerably from the information produced expertly by the CSDR team. Each member was presented with over 150-pages in a briefing package in advance of our working sessions, a package that included a wide variety of analysis dimensions and graphic illustrations, along with a rich narrative built upon seven themes as observed and interpreted by the research team.

The quantitative data components provided a comprehensive analysis of the 186 in-scope deaths across 25 institutions of varying size and character. The panel was able to examine such dimensions as age, length of custody before death, manner of death, proximity between each death and family visits, programming and health supports in place at the time, and the relative timing of lockdown conditions, among others. Some of the graphics and tables found most useful to the panel’s work are recreated throughout this report.

The qualitative data and the resulting CSDR insights were derived from almost 70 interviews with survivors who had lost a loved one, SOLGEN officials, and correctional staff including correctional officers (COs) and health care providers. The panel greatly appreciated the inclusion of personalized commentaries in the briefing package, each highlighting available details of the individuals who lost their lives while in custody. This set the tone for our opening discussions. It became evident that the panel was not solely committed to the policy and procedural aspects of our analysis. Even more so, we pledged to re-humanize the persons who suffered and died as much as possible, to do the same for all current and future persons-in-custody, and to similarly respect the needs of COs, health professionals and others who have been traumatized by every loss.

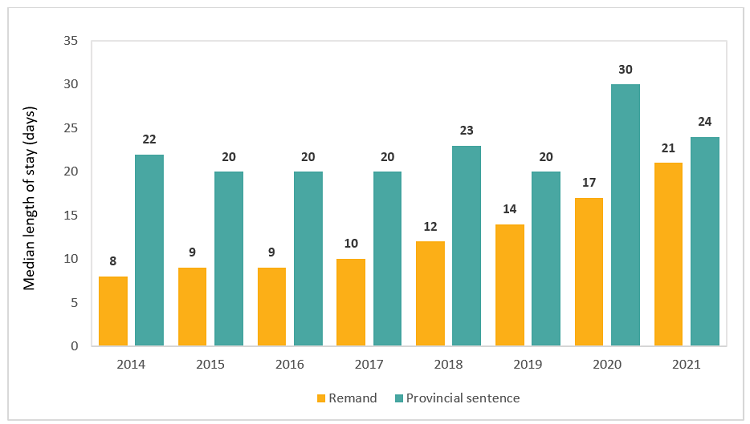

Figure 3 presents the median length of stay in custody (number of days), by hold status. In 2021, for example, the median provincial sentence served was 24 days, meaning that half of the persons-in-custody serving a provincial sentence stayed 24 days or less, and half stayed 24 days or more. The median length of stay for those on remand steadily increased from eight days in 2014 to 21 days in 2021. The median provincial sentence served was relatively stable over the eight-year period with the exception of 2020, when the median was notably higher (30 days).

To build upon the available data and deepen our insights, the panel moderator and the CSDR team worked together through the month of September to identify and schedule a total of 21 delegations who would be invited to provide their informed perspectives to the panel’s deliberations. The delegations included (not presented in order of appearance):

- family survivors;

- prisoner advocates;

- ministry officials knowledgeable in health care, prisoner transfer, inquests, finance, information technologies and infrastructure;

- specialists in CO recruitment and training;

- policy specialists;

- investigators;

- health care providers;

- community-based service providers;

- human resource and labour officials;

- labour representatives; and,

- correctional officers.

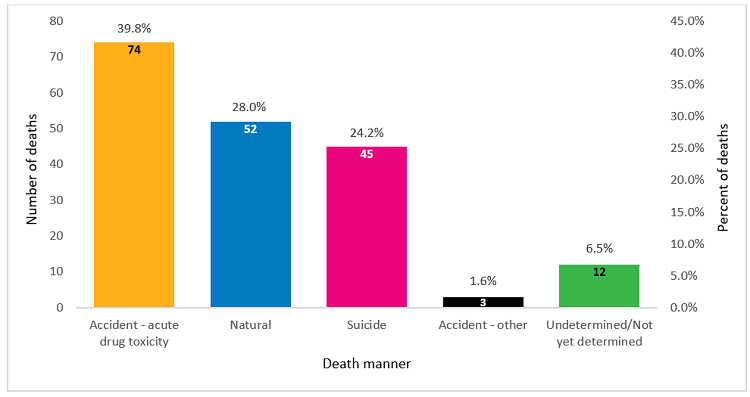

Figure 4 presents the number and percent of deaths, by death manner (see Glossary for definitions). Over the 2014–2021 period, acute drug toxicity deaths accounted for nearly 40% of deaths; natural deaths accounted for 28%, and suicides accounted for 24%.

We would not diminish the importance and value derived from every one of these contributors. However, the panel members all agree that the most impactful for us were the family survivors, and the correctional officers, for some notable reasons.

First, due to a continuing backlog in inquests — which are mandatory upon the death of a person in custody, with some exceptions in the case of natural deaths — and a host of other factors, some of which we bring forth in Part II, families and survivors have generally suffered through a vacuum of information since the deaths of their loved ones. In their conversations with the panel their emotions ran from hurt, to disbelief, to anger, and back. Said one, “Some of Canada’s worst criminals are still alive in prison after 30 years. Our son acted out from a drug problem, and he was deceased within 24 hours of being remanded to your facility. We still don’t know how or why he died.” Said another, “Everyone along the chain knew our daughter had expressed suicidal intentions right up to her transfer and admission. Why was she left alone and unwatched in a cell that included the ready means to end her own life?”

And one more said, “Our loved one had been exonerated by the courts and scheduled for release within hours of his overdose death. How and why was he able to access these toxic drugs after several weeks in custody?” Second, the many collateral impacts of the current conditions in most facilities were finely drawn by the COs with whom we met, who echoed and brought into sharper relief many similar observations provided in the earlier CSDR interviews. We learned of a work environment plagued by absenteeism, low morale, a competitive drive to avoid blame, a severely restricted ability to perform the most important and most career-gratifying aspects of the job, and a prevailing dark cloud of mistrust. Said one, “I can take prisoner interactions all day long, they are why I still like the job. It is my interactions with my colleagues and managers that is destroying me.” Said all of them as their time with our panel ended, “Help us, please.”

From our CSDR briefing materials and from our many hours of candid conversations with our delegations, something came very clearly into focus for us as a group. While the central purpose of our work remains focused on a review of the deaths that have occurred, and on the prevention of any further fatal tragedies, there is the potential for us to deliver a much wider scope of impact. The circumstances that have contributed to the in-scope deaths are the same circumstances that are placing every resident and every staff member in an unhealthy and unsafe environment every day. We submit that the extent of the harm from these enduring circumstances is much, much wider and it shows no sign of easing.

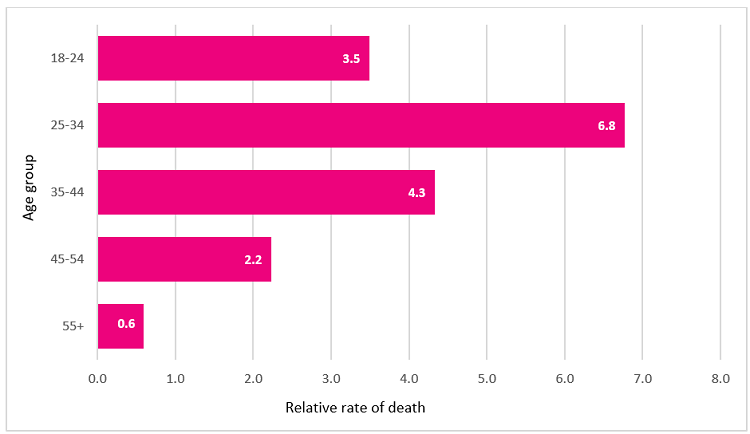

Figure 5 presents the relative rate of death among individuals in custody compared to the general Ontario population, by age group. Among individuals aged 25 to 34 years, those in custody are nearly seven times more likely to die; those 18 to 24 years are 3.5 times more likely to die in custody, and those aged 35 to 44 are 4.3 times more likely to die in custody.

On the other hand, this also means that the dividends and benefits that could derive from actionable solutions are significant and compelling. In Part II, we will discuss the key factors we identified as the most evident contributors to these circumstances. In Part III, we offer several direct recommendations for action. They are not all equal in their scope or complexity, but they are all equivalent in their urgency.

Figure 1 long description

Figure 1 presents the percent of all persons-in-custody in Ontario, broken down by their hold status (see Glossary for definitions). The percentages presented are based on average daily counts and are presented for the combined period of 2014 through 2021. Individuals on remand make up the largest proportion of the population at 68.2%. Individuals with a provincial sentence make up the second largest proportion of the population with 23.8%, while other make up 8.1% of the population.

Figure 2 long description

Figure 2 presents the proportion of deaths by hold status. In each year, individuals on remand made up the largest proportion of deaths among persons-in-custody, with the highest proportion in 2020 (91%).

In 2014, individuals on remand made up 53% of deaths in custody, individuals serving a provincial sentence made up 37% of deaths and individuals held in custody for other reasons made up 11% of deaths. In 2015, 53% of deaths in custody were among individuals on remand, 37% were among individuals serving a provincial sentence and 11% were among Other. In 2016, 77% of deaths were among individuals on remand, 15% were among individuals serving a provincial sentence and 8% were among Other. In 2017, 74% of deaths were among individuals on remand, 13% were among individuals serving a provincial sentence and 13% were among Other. In 2018, 67% of deaths were among individuals on remand, 25% were among individuals serving a provincial sentence and 8% were among Other. In 2019, 64% of deaths were among individuals on remand, 20% were among individuals serving a provincial sentence and 16% were among Other. In 2020, 91% of deaths were among individuals on remand, 9% were among individuals serving a provincial sentence and there were zero deaths among other hold statuses. In 2021, 80% of deaths were among individuals on remand, 11% were among individuals serving a provincial sentence and 9% were among Other.

Figure 3 long description

Figure 3 presents the median length of stay in custody (number of days), by hold status. In 2021, for example, the median provincial sentence served was 24 days, meaning that half of the persons-in-custody serving a provincial sentence stayed 24 days or less, and half stayed 24 days or more. The median length of stay for those on remand steadily increased from eight days in 2014 to 21 days in 2021. The median provincial sentence served was relatively stable over the eight-year period with the exception of 2020, when the median was notably higher (30 days).

- In 2014, the median length of stay for those on remand was eight days, and 22 days for those serving a provincial sentence.

- In 2015, the median length of stay for those on remand was 9 days, and 20 days for those serving a provincial sentence.

- In 2016, the median length of stay for those on remand was 9 days, and 20 days for those serving a provincial sentence.

- In 2017, the median length of stay for those on remand was 10 days, and 20 days for those serving a provincial sentence.

- In 2018, the median length of stay for those on remand was 12 days, and 23 days for those serving a provincial sentence.

- In 2019, the median length of stay for those on remand was 14 days, and 20 days for those serving a provincial sentence.

- In 2020, the median length of stay for those on remand was 17 days, and 30 days for those serving a provincial sentence.

- In 2021, the median length of stay for those on remand was 21 days, and 24 days for those serving a provincial sentence.

Figure 4 long description

Figure 4 presents the number and percent of deaths, by death manner (see Glossary for definitions). Over the 2014–2021 period, acute drug toxicity deaths accounted for nearly 40% of deaths (74 total deaths); natural deaths accounted for 28% (52 total deaths), suicide deaths accounted for 24% (45 total deaths), accidental deaths accounted for 1.6% (3 total deaths) and undetermined/not yet determined deaths accounted for 6.5% (12 total deaths).

Figure 5 long description

Figure 5 presents the relative rate of death among individuals in custody compared to the general Ontario population, by age group. Among individuals aged 25 to 34 years, those in custody are nearly seven times more likely to die; those 18 to 24 years are 3.5 times more likely to die in custody; those aged 35 to 44 years are 4.3 times more likely to die in custody; those aged 45 to 54 years are 2.2 times more likely to die in custody, and those aged 55 and older are 0.6 times more likely to die in custody.