Part two: Actionable factors contributing to unsafe conditions in Ontario corrections custody facilities

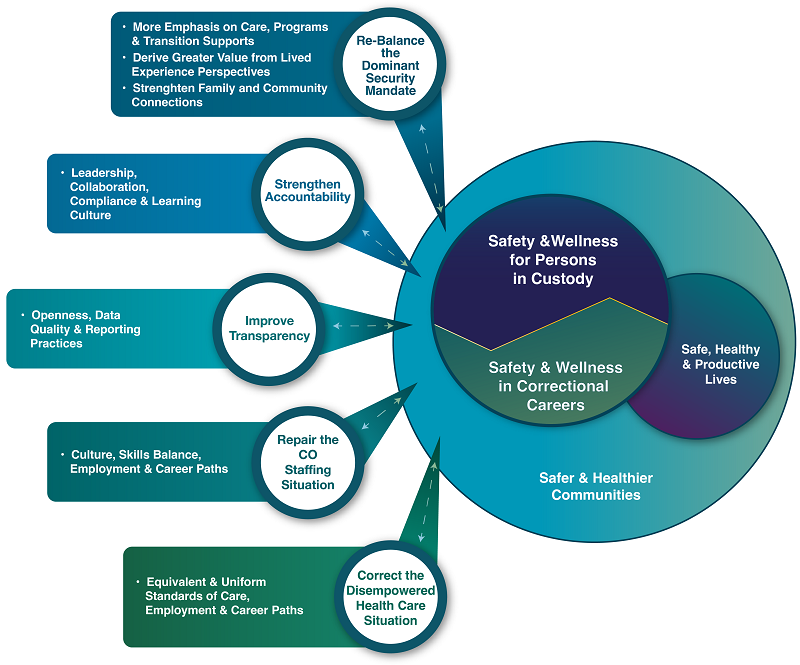

We have organized our observations into five themes as depicted in the illustration below. It is important to stress the interactive nature of these themes, and several of our resulting recommendations will address more than one. Collectively in our view, the conditions described in the following narratives have coalesced to create a corrections environment in Ontario that is fundamentally unsafe, outmoded and misaligned with the aims and modern needs it is intended to serve and support. By addressing each theme separately in the narrative, we hope to make specific actionable conditions clear to everyone with a role to play.

Figure 6 depicts a range of factors currently contributing to reduced safety in Ontario custodial facilities, where key opportunities exist to prevent deaths and serious injuries to persons-in-custody, to improve the safety and well-being of correctional staff, and to support better outcomes across the criminal justice system.

We believe that action is urgently required in every area we have identified. We are grateful to the CSDR team and to all of our contributing delegations for the candor and constructive suggestions that have brought this urgency into clear focus. Among staff and stakeholders, we encountered a common willingness to learn and a shared commitment to act. As such, we are optimistic that with greater clarity and illumination of these issues and concerns, actionable remedies exist and are realistically achievable in the short and medium term.

A. The mission: An urgent need to re-balance the apparent mandate for security and control

As is the case with many of our long-standing institutions, today’s public service professionals have effectively inherited systems and workplace cultures with long and deep origins. Such cultures can be reflected in everything from decades-old infrastructure, prevailing language and the myths that help to shape everyday interactions. In turn, they can manifest in the decision-making reflexes of everyone in the system. In corrections practice, Ontario has long pursued more progressive policies, new structural choices and corporate-level decisions designed to reflect evidence-based correctional practice, as has our entire criminal justice apparatus to a large degree. Much progress has been achieved, and this was clearly reflected in the knowledge and attitudes our panel encountered. However, it also appears that too many artifacts of the past continue to dominate the day-to-day reality in Ontario’s 25 correctional facilities.

In many ways, fully embracing modern practices is a luxury that can be easily denied to any system that is operating at a breaking point. With little capacity available to managers and staff, systems will often default to a more apparent and so-called mission-critical mandate. This appears to be the case for Ontario corrections, and that apparent historical mandate for custody and control is all but silencing the alternative: a progressive emphasis on care, wellness, supportive programs and effective transitions to living in the community. Unfortunately, this is occurring at a time in our society where these more progressive practices are required more than ever before, and if applied fully, they would be much more compatible with the realities and needs of today’s prison population.

We found clear and repetitive evidence of this phenomenon revealed in many ways, just some of which are highlighted below:

The default to maximum security

The facilities in Ontario are almost completely configured for maximum security custody, despite the fact that only a small percentage of persons-in-custody have been charged with crimes of violence. This alone transmits a culture where control is the apparent and dominant priority. We were encouraged to learn of the Security Assessment for Evaluating Risk (SAFER), an innovative tool for evaluating a person’s risk for misconduct at the time of admission and throughout their term of incarceration. This tool supports staff in anticipating and mitigating improper behaviour. Some noted the risks of inequities in its applications, and this is an area deserving of attention and improvement.

Isolation and de facto segregation

We understand the infrastructure challenges in changing facility design in short order. But we were deeply concerned to learn that it is actually front-line decisions that can often override even the best attempts to provide the most risk-commensurate environments. Undoubtedly for a host of reasons, the CO staffing levels have fallen to such a critical state that frequent lockdowns are the routine response. When lockdowns occur, programming cannot take place, and health care and spiritual supports as well visitations may also be canceled or interrupted. In addition, capacity limitations often require isolation simply due to over-crowding, for example, when there is no alternate safe space for women or gender diverse individuals introduced into a facility with a general population dominated by men. As noted in the sidebar above, the COVID‑19 situation certainly accounted for a sharp increase in similar conditions out of public health necessity. We also learned that the recently updated segregation policy is often circumvented by lockdowns and other short-term operational reasons. This policy is designed to limit and track placements of persons-in-custody in highly restricted conditions for 22 to 24 hours or persons-in-custody that do not receive a minimum of two hours of meaningful social interaction each day.

An imbalance in CO training priorities

To the extent that we were able to learn about curriculum, it was evident that the dominant language tends strongly toward control. Certainly, COs and others fully deserve to put safety at the top, and to acquire the necessary knowledge, skills and abilities (KSAs) required for the management of the most risky and dangerous circumstances. But, absent a broader competency model, and with insufficient capacity and rigour in achieving in-service training compliance, it appears that most COs have only cursory development in the aspects of emergency care, mental health, trauma and violence-informed practices, and other supportive aspects of their modern role requirements. Alarmingly, there also seemed to be little appetite to date to address these learning gaps, and training appeared to us tomerita generally low priority across the system. For unknown reasons, there is little transparency to the entire staff development processes that currently exist, and very little opportunity for others to engage outside of those with direct responsibility for the current training regimes.

A consistent devaluation of lived experience, family and community perspectives

When our panel inquired about the active involvement of individuals with lived experience in the scenario-based components of CO training, it appeared we were speaking a foreign language. This occurred again and again in our discussions with delegations and revealed a prevailing attitude that places low priority on including anyone outside of the officials who operate the system. It was evident again in the long information gaps that have frustrated and isolated family survivors, although we were very encouraged by the recent introduction of the Family Support Liaison position (we offer more on that below). It was evident in the lack of feedback provided from investigations, beyond that which is obligatory and typically restricted to superintendents and their regional directors. It was also evident in the denial of any form of spiritual commemoration of lost lives, inside or outside of the facilities.

The unofficial abandonment of supportive programming

It would be unfair for us to assert that programming does not exist. We learned of many valiant efforts to bring supportive programs to persons-in-custody, often in creative and adaptive ways. Much of this programming is delivered by community-based agencies with strong reputations and metrics that validate the quality of their services. However, interruptions to access due to lockdowns, general staff unavailability, fiercely competitive access to suitable gathering spaces, have conspired to reduce program consistency in the extreme. We learned from lived experience contributors that this results in a prevailing experience of boredom. We also learned of a direct connection between that dispiriting monotony and the growing and unrelenting demand for potentially toxic substance use, and we know that the connections between isolation and suicide are already well documented. This extends to include the all-important transition planning that can connect departing persons-in-custody with appropriate community supports and health care continuity. Again, due to capacity limits, these vital connections are routinely sacrificed.

Punishing disconnections from family, community and professional supports

Collectively, the policies, facility designs and current capacity limits have limited both inside and temporary absence visitation and humane family and social connections to a degree that is completely out of step with the expectations of a modern and caring approach to incarceration. While the reasons may be complex, the message this sends to everyone involved is that social interactions and connected relationships simply do not matter. Again, the evidence with respect to suicide, accidental deaths by toxicity and the general unwellness that can lead to early natural deaths overwhelmingly says that this matters a lot. Connections to family, friends and supports are well documented factors that can protect against exacerbating mental health conditions while promoting greater wellness and supporting reintegration. When these connections are as tenuous as they have become in our prisons, health conditions can worsen, and the lack of connection can play into the boredom cycle with tragic results.

In our recommendations in Part three, we identify several immediate steps that if taken together, could solidly establish a new concept-of-operations for Ontario corrections, one that will both improve individual and community outcomes and save many lives in the process. In turn, the broad enculturation of this renewed and re-balanced concept will drive different decisions at every level, from the micro to the macro. As evidenced in other systems and business sectors, this can spur a new level of innovation and creative adaptation, both of which will be required to ensure that long established infrastructure does not remain the sole defining symbol of what matters to us in 21st century Ontario.

B. Accountability: An urgent need for more assertive and collaborative leadership, rigorous policy compliance and a learning culture

It is always challenging to direct specific observations toward any identified sub-set of the system. We acknowledge from the outset that the individuals who occupy the positions of greatest influence are themselves committed to achieving the best outcomes, and often find themselves restricted by history, by bureaucratic inertia and by the more complex interconnections between their own span of control and other parts of the broader system. It is our hope that our observations and recommendations under this theme might grant greater license to those executives and managers, and perhaps amplify and accelerate the improvements and innovations they have already attempted to advance.

For reasons unknown to the panel, the current model of corrections in Ontario appears to have been left in a somewhat isolated state, where almost all evident accountability is internally focused. While the system accounts for a significant portion of the provincial public service, it seems fair to observe that it receives from senior government only a small fraction of the attention it requires. We view this Coroner’s review, as unfortunate as it is, as an opportunity to ensure these lost lives receive the response from the full system that they deserve.

We have identified many aspects of accountability that can and must be strengthened, just some of which are as follows:

Policy and practice gaps

The isolated state of the corrections system within government as described above appears to be replicated within, much like a set of those decorative nesting dolls, at the ministry level, the regional level, by single institution, and all the way to the level of the range. The data from Correctional Services Oversight and Investigations (CSOI) on deaths and other critical incident investigations reveals astonishing levels of non-compliance with long-established and well documented policies. We were left to wonder if this points to an epidemic of ‘going rogue’, or if perhaps too many of the policies cited are out of step with operational realities. We also discovered an interesting dichotomy, in which senior executives cite local and regional autonomy as an explanation for non-compliance, or at least varied interpretations of compliance, while local and regional managers commonly cite strict system-wide uniformity as a reason for not implementing creative and innovative solutions. At the front-line levels, this has contributed to a prevailing atmosphere of fear, where no CO wants to be the last doll to be unpacked, the one to whom a policy or standing order breach can be attached, and thus the one left to take sole career responsibility for a long chain of uncertainty and confusion. It would appear that such consequences at the front line can often be immediately career limiting ones. Further up the line, we were unable to detect any notable pattern of consequence, even amid the disturbing pattern of deaths being experienced in recent years. We can only conclude that this is largely due to the diffuse state of accountability that exists.

Learning gaps

Among a number of concerns with the foregoing, perhaps the most troubling is the lost opportunity to learn. Within a prevailing fear of blame at the front line, and a prevailing deference to regional and local autonomy at the top, it appears that rarely is anyone engaging in the collaborative deconstructions of critically important events sufficiently to discover and apply valuable learning across the system. We note that, to the extent that learning is being considered, there appears to be a pattern of independent analysis at the Superintendent level, or at most, some accountability at each Regional Director’s scope of responsibility. From our consultations, we did not discover any real pattern of system-wide learning, including in the face of CSOI investigations and even Coroner’s Inquest results. It does appear that periodically, institutions of similar size and character might share experiences and outcomes, but this also appears to be ad hoc and at the discretion of those managers involved. Ultimately, there is no doubt that important opportunities to improve the safety, care and support to persons-in-custody are being lost. Conversely, a deliberate and coordinated pattern of collaboration across the 25 institutions could unleash a continuous improvement environment, and likely reveal the most intractable barriers to change that are being experienced by the staff and managers in every facility.

The role of leaders in setting the tone

Several of the recommendations that are principally connected to our first theme also have direct relevance here. If the system is to embrace and reflect a re-balanced mandate, it will be incumbent on every leader, at each successive level of responsibility, to ensure that this is reflected in their everyday interactions with those who report to them. If a new set of framing principles can be developed, with the benefit of an inclusive approach as we propose in Recommendation# 1 below, then those principles should remain top of mind in every decision and interaction that occurs in the normal operations of each facility.

C. The data situation: An urgent need for greater transparency with consistent, open and reliable reporting throughout

Our review’s insights into this theme emerged well before our panel began its work. The CSDR research team struggled to access, interpret and apply data sources that ranged from archaic paper methods, to incomplete electronic records, and often illogical reporting patterns. They also encountered organizational units whose responses to their information requests ranged from eagerly cooperative to only tacitly willing. Our visiting delegations helped to further illuminate why some of this might occur. The data quality across the system is well below modern expectations, and it appears that just about everyone involved is aware of this condition.

Beyond the availability and application of quality information, it also became very clear to the panel that across the entire system, there is an evident reluctance to share information.

For the most part, we detected simply a self-protecting or system-protecting need-to-know culture, coupled with an evident attitude that very few deserve to know. Again, this appears to extend from senior policy maker levels, to regional and facility mid-managers, and to the front line where COs can serve as open or closed gateways of information, however they might choose. Unfortunately for persons-in-custody, this is a dangerous environment where it has been demonstrated far too many times that what other people don’t know, can kill them.

Jointly with the CSDR team, our panel has identified several of the most urgent opportunities for improvement in transparency, data quality and general reporting behaviours, highlighted as follows:

The acute vulnerability of silenced individuals

For disempowered individuals, the difference between being heard or silenced rests with others in positions of power and control. In addition, the ability to be heard without fear of retribution, including sometimes violent retribution, is similarly in the control of others. The most cynical reasons we heard for blocking voices from the range is that control and order might necessitate tempering complainers and disrupters. Fair enough, we understand that such situations can apply. But there is still only one gateway available to most, and what if the information being silenced at that gate could contribute to deteriorating health or safety, for the individual and/or for others? Under the current information regimes, it is impossible for us or anyone to provide empirical evidence that blocked information has contributed to deaths, or to what specific degree a more open flow might have saved a life. We can offer with certainty that we encountered a striking gap between what is said to occur on the range, in official records or notes when available, and what is actually happening, based on insights gained from our lived experience and family or advocate sources. To avoid further harm, this gap demands the immediate design and adoption of more reliable and failsafe systems and practices to support the safe flow of information from persons-in-custody to those who need to hear their voices, and those with the ability to act in protection of their health and well-being.

Information gaps at time and place of transfer

With a high proportion of the in-scope deaths occurring within hours or days of admission, it is essential that the hand-off from courts to prisoner transport, and onward to the Admissions and Discharge (A&D) units be both seamless and as free from human error as much as possible. Current systems do not rise to these standards. We learned of free-form paper notes which may or may not be sufficiently complete or accurate, which may or may not survive the transfer process, and which may or may not be read on receipt with sufficient diligence.

Investigations and the application of outcomes and intelligence

Our panel was encouraged by the continuing investments in the Correctional Services Oversight and Investigations (CSOI) division over the past several years. This is a vitally important function. To date CSOI, which also includes the Ontario Corrections Intelligence Unit (OCIU), has yet to achieve the capacity and scope required. The combined units currently lack sufficient ability to provide data-based evidence to identify trends and deliver analysis, to address gaps in policy and identify training needs, and to provide strategic support to management to mitigate identified risks to safety and security in the 25 institutional settings. Limited CSOI resources are spread thin as they must currently serve both the custodial facilities and the community parole and probation operations of the correctional system. In addition, CSOI does not currently have the necessary access to all relevant corrections databases to support efficient and relevant intelligence dissemination, or to ensure the broadest depth and application of investigative outcomes.

CSOI reports a growing reliance among operational leaders on its findings and data related to such urgent issues as deaths in custody, contraband trafficking, prisoner on prisoner assaults and use-of-force situations. However, the unit requires expanded analytic capabilities and updated technology and information systems to ensure that investigations and intelligence outcomes will lead to improved application of policy and practice in real time and across all facilities. Given the alarming patterns of harm identified through this review, our panel believes that priority consideration should be given to expanding these capacities, and perhaps raising CSOI to the level of a full Inspectorate identity and functionality as recently adopted in the provincial policing system.

Expanded capability in the Offender Tracking Information System (OTIS)

It is a reasonable expectation that once an individual enters a provincial correctional facility, at minimum, records of their institutional location, placement and experience in custody will be adequately kept and recorded. Although this is currently viable through the Offender Tracking Information System (OTIS) — the main electronic database used by Ontario Corrections to track individuals in custody — our panel learned from the review team and the delegations that this is not always how it is applied in practice. Due to a mix of issues stemming from technological limitations to operational and procedural barriers, including a lack of access to OTIS for institutional staff and an absence of quality standards guiding data inputs, information is often incomplete, unverified or otherwise omitted in the electronic database. This jeopardizes the integrity of the information collected and unnecessarily contributes to unsafe situations, for both staff and persons-in-custody.

One gap that was particularly concerning to our panel, raised repeatedly by institutional staff, was the lack of access to OTIS for all staff involved in a person’s care (e.g., NILOs, chaplains, etc.) and the alarming level of data that is carelessly omitted as a result. Without consistent access to OTIS to accurately record all provider interactions and program delivery, the benefits and opportunities of OTIS as an information management system are not being sufficiently leveraged. Without a complete picture or understanding of a person’s unique situation, it is almost impossible to adequately meet and address their needs. A database such as OTIS can only be an effective information tool if all necessary staff are able to access it consistently and reliably.

For those who do have access to the electronic system, the panel also heard concerns not just regarding the limited information that is available in OTIS, but also regarding the quality of the data that is captured. Quoting one interviewee, “The suicide flag can be pretty vague. It might say ‘2001 previous attempt’, but it won’t have any details. It depends on who is admitting the person, the documents or updates in OTIS, and whether they have more experience with the individual as far as their charges or their medical history.” Our visiting delegations further echoed this by describing an environment in which staff are pressured to adopt a ‘less is more’ approach when inputting data into the system, and where information sharing among staff is often determined by rank within the institution.

As the main electronic data source for Ontario Corrections, there is an expectation that this system should be as reliable and free from human error to the greatest extent possible. However, much like the information gaps noted above during transfers, the current electronic database does not rise to the level of quality record-keeping or data standards required for reliable information sharing, analysis or operational management.

It would be beneficial to expand access to OTIS for all front-line staff so that data currently recorded in physical logs can be archived digitally. While there may be issues around data protection to be resolved, OTIS could be utilized to record medical records, with access given to staff under strict confidentiality protocols. In addition, the panel believes that this primary data system must also reflect the balanced mission discussed above, and in that regard, the term ‘offender’ should be removed from use in its title.

Open access performance metrics

Our panel was surprised by the lack of openly available metrics and basic performance and incident data, as discovered throughout the research phase and as further revealed in our deliberations. We note that this apparent bias to not disclose information appears to be out of alignment with the open data philosophies and practices adopted across the Ontario Public Service. An evident reluctance for transparency, whether by policy, implicit policy, or simply out of historical habit, risks undermining both public trust and employee confidence in the correctional system.

Conversely, as is being exhibited in other spheres including health, public health, education and policing, public-facing information can drive system improvement and innovation in response to concerns and opportunities raised by more widely informed voices. A full analysis of how a more open data posture, and the degrees to which openness can be applied, is beyond the scope of our panel. However, we believe the contributing factors outlined in each of our identified themes would benefit from higher degrees of visibility and from the corresponding drivers for change that such information can generate, and we strongly encourage Ministry action in this direction.

D. Correctional officer staffing and employment: An urgent need to restore capacity and advance a culture for safety, care and employee wellness

We begin our observations in this section with an acknowledgement that no report of this nature could ever do justice to the complexity and diversity of daily and career-long workplace experience for correctional employees across 25 different institutions. These are careers that require courage, compassion and dedication, attributes that were consistently identified in CSDR interviews, in questionnaires, and in our panel discussions with COs, their labour representatives and the Ministry officials most informed about staffing, training, labour relations and human resources management. Further evidence from the tenure patterns of current officers reveals that many spend the majority if not all of their career within the Corrections system. This indicates their commitment to the mandate and the importance they see in their role in the justice system.

Collectively, they described a lot of positive change that is underway and made it clear that staff are generally proud of their careers and the work they do. As one delegate phrased it, “There is a lot of work left to be done, but we are on a good road by acknowledging the importance of focusing on opportunities, not deficiencies.” To quote another, “Systemically, it is hard to do the job to the level we would like to. Correctional officers have the same goals as this Expert Panel: to address the unsafe environment and aspects of harm involved in the system. We would like to see recommendations that can address these concerns.”

Our panel learned again and again that it is impossible to separate the tragic impacts of in-custody deaths. They are tragedies for individuals and their families, and every such event is another traumatic experience for the employees, sadly punctuating their everyday awareness of the risks faced by persons-in-custody and staff in these environments.

For the purpose of this review, we have identified what the panel regards as the most apparent and urgent areas related to staffing, employment and workplace culture, areas where opportunities for greater safety and well-being can be pursued for the benefit of everyone involved. These include:

Ongoing short-staffed conditions are undermining morale, staff wellness and safety, staff effectiveness and safety for those in custody

Our panel encountered a litany of causes and potential remedies related to the chronic inadequate staffing conditions, but ultimately, the message was that this pattern represents a clear and present danger to everyone, and it is likely among the primary contributing factors to the alarming rise in deaths in custody.

| Lockdown type | 2014 % |

2015 % |

2016 % |

2017 % |

2018 % |

2019 % |

2020 % |

2021 % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staff shortage | 75.0 | 95.8 | 88.6 | 81.0 | 64.9 | 82.1 | 82.4 | 92.9 |

| Search | 25.0 | 3.2 | 5.8 | 10.6 | 20.3 | 11.4 | 8.2 | 3.1 |

| Health care | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.8 | 1.2 |

| Administrative maintenance | 0.0 | 1.0 | 4.4 | 8.2 | 12.4 | 6.5 | 6.8 | 2.2 |

| Inmate behaviour | 0.0 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 2.4 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.6 |

| Local investigation | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 2.7 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.4 |

Note: Data are incomplete for 2014 and 2021. Incidents are self-reported, and results should be interpreted with caution. Variations may be the result of incomplete reporting.

Figure 7 shows the various causes that have triggered lockdown conditions across all custodial facilities in Ontario. In the eight years studied, the percentage of lockdowns due to staffing shortages has averaged above 82%.

We note that there are two levers available to senior decision makers, and by extension, to their partners across the criminal justice system and in senior government. One or both of these levers will need to be acted upon, or the unsafe conditions in Ontario custody facilities will most certainly continue, with a high potential to worsen in the years ahead.

The most directly actionable of these levers for the Ministry alone would be to increase staffing levels. There are a host of barriers and counter-indications to relying solely or even primarily on this option. It is already difficult to manage adequate attraction, recruitment, training and deployment at current staffing levels. At the same time, most of the physical environments are similarly stretched beyond capacity. There are few if any indications of an appetite for increasing the correctional services capital or operating budgets. Perhaps most importantly, adding further custodial infrastructure would run counter to emerging best practices in criminal justice and community safety and well-being.

The much more promising option is to act on the demand side of the equation. The second lever would be to systematically reduce the reliance on correctional custody as an over-used solution to those persons who present with complex needs but who also represent minimal and/or otherwise manageable risk to the community.

The panel also recognizes that individuals successfully diverted from incarceration will require adequate community supports and sufficient human service investments across the social determinants of health and well-being. The panel is confident that the literature and experience indicates that such supports can offer significantly more efficiency and effectiveness, wherever the operating criminogenic factors are minimal enough to ensure safe living in the community.

Permanent versus fixed-term employment arrangement fosters competitive dynamics and increased turnover

Even without increasing staffing levels, there are additional conditions that can be addressed to increase safety. Notable among these is to place greater urgency on restoring a healthy workplace environment for all employees. The panel determined that the current stratified employment model is contributing to a stressful and unhealthy work environment, and thus heightening operational gaps that can translate to unsafe conditions for persons-in-custody.

We learned of an evident hierarchy and power imbalance that exists at the front-line between permanent employees and fixed-term employees, the latter often existing in a precarious state for several years, and far more vulnerable to punitive action by management as a result. In addition, we learned that the mixing of these two classes of employees on the same range raises risks of inconsistent practice and a significant blame-avoidance scenario where opportunities for important learning are suppressed.

We heard from employees, labour and human resources representatives that unravelling this staffing model is a complex challenge. But at the same time, all of them indicated it is a defining negative factor in the current CO culture.

Employee and labour perspectives (among others) are excluded from active partnership in systemic improvements

Our panel found that from our own experience, when compared to other public service sectors, the custodial corrections system appears to be out of step with cooperative management models that have emerged in the past few decades. First, two separate domains appear to exist, with one representing ‘corporate’ functional units, and the other being the vast operational environment where the bulk of employees are. There is a sense that these domains often act in isolation from one another. Secondly, within that operational domain, we discovered little evidence of structured engagement arrangements, other than the joint health and safety committee that is a mandated practice in Ontario. Employees and their labour representatives described being isolated from decisions, from information about critical incidents from which learning could derive, and from opportunities to contribute their direct front-line experience to systemic improvements and innovations. Labour representatives have concerns they are viewed by management almost exclusively as a barrier, and not as a willing partner, despite their assertion that any systemic improvements that could benefit the effectiveness and wellness of their members are among their highest priorities.

This is not a universal problem, as we also heard from executives and front-line COs of managers who are open to trying new approaches and who exemplify highly engaged and empowering practices. On a systemic level, however, one employee may have summed it up best, with, “There is almost never a teaching moment.”

Training models defy constructive review

Our panel was not provided with sufficient information about the current training regimes to offer conclusions with any degree of confidence about their scope, effectiveness or appropriateness to the roles of all employees and managers. We have described the general prevailing lack of transparency elsewhere in this report. Nowhere was this more evident than in our attempts to decipher current training and staff development practices. In the research phase of the review, the CSDR team struggled to access and understand the fragmented records that exist, but at best, they were able to determine that significant gaps appear to exist in the compliance and completion levels for in-service learning programs.

In discussions with our delegations, the panel learned that there is a shared awareness of the need for an increased emphasis on mental health, crisis prevention and informed responses to substance use situations. However, it seems that little traction has been achieved to date. As well, we learned of a system that appears to operate without much evaluation of outcomes, feedback loops from the workplace realities, or simple debriefs in the course of learning completion. There is currently no lived experience that we could identify, including in the design and execution of new experiential and simulation components being recently introduced. Moreover, while the ministry retains responsibility for applied learning in the basic training for COs, theoretical aspects of training have been outsourced to a third-party provider with some oversight provided by the ministry.

Throughout the foregoing section, we have avoided commenting on the routine operational behaviour and practices of COs and other corrections employees. We recognize that toxic attitudes and errant behaviours can and do arise in any workplace. When they arise in the context of a significant power imbalance, there is no doubt that the consequences for persons-in-custody can be inhumane and dangerous. However, we also learned that many COs and their representatives are committed to addressing unprofessional behaviour in the workplace. They are indeed proud of their work, and their commitment and endurance are reflected in an above-normal retention and tenure in corrections careers, as compared to many other sectors. We found the balance of care and security to be genuine in their self-concept, combined with a self-awareness that has staff eager to benefit from higher degrees of training in all aspects of care and harm reduction on the range. In our view, and for the most part at least, staff are trying to do all of these things to the best of their abilities under the very difficult circumstances that surround them.

E. The health care situation: An urgent need to correct the disempowerment and establish stronger connections to uniform standards of care

This theme is presented last in our report, certainly not because it is the least important, but because in many ways it flips the script on our discussion thus far. Much of the foregoing has examined how custody and control can be managed with greater care. In this section, we examine how that all important care might be better managed within the unique context of provincial custody.

The citizens of Ontario benefit from one of the most progressive and available health care systems in the world. Like all systems it has its imperfections, but most of us have come to recognize and expect a consistently high standard of care. For decades in Canada, this presumptive expectation has become an enduring source of national pride. Persons entering provincial custody do not forfeit their right to health care. Especially today, amid the varied reasons for which we are placing many of these persons into custody, they and their families have every reason to expect that they will continue to have access to excellent, and equitable, health care in custody.

Within the broader scope of this care discussion are the nurses, doctors, psychiatrists, psychologists and social workers, as well as the spiritual and cultural advisors, who collectively represent more than eight percent of correctional staffing and contractual employment. Each of these professionals brings to their work the same standards of practice, ethical guidelines and personal commitment to excellence that they share with their counterparts working in hospitals, clinics, offices and places of worship elsewhere in Ontario. When working inside, their professional roles and effectiveness may be compromised due to the peculiarities and unique challenges of operating in an environment where security and control are usually the dominant considerations.

Our panel heard evidence of many such challenges which have undoubtedly contributed to tragic outcomes, and on which action must be taken if further tragedies are to be prevented. We feature below some of the most apparent and critical opportunities that have shaped our recommendations for action:

Health care is an imperative too often denied

We have discussed the significant impact of lockdowns earlier in this report, and lockdowns are not the only situations that are impeding health care workers from doing their jobs. Often, due to staffing shortages in a particular range, or the emergence of an unsafe incident that has yet to be resolved to everyone’s satisfaction, or simply procedural delays in the admissions process, COs may make decisions that restrict access to treatment and supports. These resulting access restrictions can extend to hours, or even to several days. They may also extend to restrictions on off-site medical and professional visits, which may be frequently denied due to similar decisions.

Across our varying delegations, our panel was dismayed to learn of an alarming culture of mistrust between correctional officers and health care staff. Captured succinctly by one delegation, “We all have one common goal to provide care, but everyone is against each other. We need to be one team. Staff need to be aware of each other’s roles and how we work together.” While disentangling this culture is certainly complex, it is a priority that cannot be ignored.

The risk of confusion stemming from mistrust argues strongly for a review of decision-making authorities. Such authorities may be essential to providing expedient health care, more comprehensive and appropriate health assessments at intake, attention to health and well-being challenges for those in isolation, and early access to essential mental health supports. The panel recognizes that some situations may always require decisions in favour of security for the safety of everyone involved, but the evidence suggests that the line between safety and operational convenience is currently difficult to discern, and undoubtedly difficult to navigate. The situations that have resulted in tragedies cry out for much greater clarity in this regard.

The nursing employment problem

Not unlike the stratified employment problem amongst fixed-term and permanent correctional officers, similar difficulties in retention, recruitment and compensation are contributing to significant staff shortages within correctional health care. Time and again from our delegations and the CSDR team’s interviews with staff, health care staffing vacancies and a lack of institutionally based staff were cited as common issues impeding the delivery of health care within provincial institutions. This is a critical issue for a multitude of reasons. Without adequate staffing levels to maintain optimal operations, it is not uncommon for persons-in-custody to experience longer wait times to see health care providers, delays in prescription medication access while awaiting assessment, and an overall level of deteriorating care for people in custody due to large staff caseloads. Correctional health care staff are being stretched thin beyond their institutional capacity.

Nurses have long been in high demand across the entire health care system in Ontario, contributing to a highly competitive market for hiring and retention. Rates of pay, benefits and working conditions differ across the many workplaces that employ nurses. Employment practices range from full-length careers to often-precarious contract terms and agency-based engagements; the latter nonetheless sometimes preferred by nurses for professional and personal reasons.

When both employment and contract arrangements are mixed within a single organizational environment, this can lead to inconsistencies in practice, challenge reliability in staffing levels and introduce unforeseen consequences in the quality and safety of everyone involved — this is the case in Ontario’s custodial facilities. Our panel learned of variations in the level of training between employed and agency-based nursing staff, variations in their real and perceived authorities to make health care decisions, and a continuing challenge to maintain the required complement of the most qualified nurses, including those with adequate knowledge in mental health nursing, in each facility and across the full system.

When asked to consider what might be contributing to the lack of health care staff, we received the same answer, without hesitation, every time: a lack of competitive wages between corrections-based positions and other health environments. Quite simply, compensation and employment conditions within corrections are failing to compete with other health care environments outside of the corrections sphere. Until this competitive disadvantage is resolved, it is reasonable to expect that the issue of health care staffing is unlikely to improve.

The misalignment with provincial health practices and standards of care

Health care in provincial correctional facilities is overseen and delivered by the Ministry of the Solicitor General. Rather than a model in which health care in provincial custodial facilities is fully integrated with health care in the community, health care in provincial correctional facilities operates in a separate silo. Progressive provincial and local health care initiatives often fail to include correctional facilities in their planning and implementation. Correctional facilities bear their own burden of establishing relationships and procedures with community practitioners and organizations. As a result, health care quality and accessibility are often substandard, and there is a lack of continuity of care for people entering incarceration and upon release.

Like all others across Ontario, persons-in-custody should reasonably expect:

- timely evaluation of medical and/or psychiatric concerns;

- prompt institution of treatment and continuity of care at the currently accepted,evidence-based standards for this province;

- regular and appropriate monitoring for identified conditions — noting that in particular, mental health problems are almost universally chronic and often demanding of care in perpetuity;

- that referralsbe made when outside expertise is necessary;

- assistance with anticipated transition to the community (i.e., continuity of care).

Explicit attention is urgently needed to achieve and sustain equity in health care and to align standards of care in custody with community standards. To prevent further tragedies, the mandate of custody and control must never be allowed to diminish or interfere with standards of care, or to undermine the professional obligations and independence of health care providers. There is no provision in any professional regulatory body thatallows for, or in any way tolerates, the provision of differing levels of quality or adequacy of health care.

This applies equally to general health care, mental health care and addiction services for persons-in-custody.

As with the previous section, we did not elect to focus this health care discussion on the specific performance and behaviours of health care staff as they undertake their roles to the best of their abilities. The evidence available to our panel raised no concerns with the professional knowledge, skills or personal attributes with which correctional health care staff endeavor to perform their duties. With other career options available to them, there can be no question of the dedication, commitment and compassion that inspires them to choose to apply their expertise in service of persons-in-custody, and to work in environments with such unique and often frustrating challenges.

Summary of part two: Distinguishing prevention from cause

Throughout this section we have sought to distill and present a broad range of factors on which our panel believes action can and must be taken. They are presented in five distinct themes for ease of understanding, but it is important to note that none of these themes stands in isolation of the others. Our recommendations, which follow in Part III, are designed to guide a system-wide response on several fronts.

We also believe it is important to note that no single factor, nor any specific combination of these factors, can be said to have caused any specific death, nor any group of deaths. In this, our mandate differs from an inquest. Our mandate is to help us all to understand how these factors contributed, collectively, to an overall custodial environment in which these deaths were not avoided. In this, our shared obligation is to prevent.

Figure 6 long description

Figure 6 depicts a range of factors currently contributing to reduced safety in Ontario custodial facilities, where key opportunities exist to prevent deaths and serious injuries to persons-in-custody, to improve the safety and well-being of correctional staff, and to support better outcomes across the criminal justice system. The five themes depicted in the illustration are discussed throughout the following subsection and include: Re-Balance the Dominant Security Mandate, Strengthen Accountability, Improve Transparency, Repair the Correctional Officer Staffing Situation, and Correct the Disempowered Health Care Situation.

Figure 7 long description

Figure 7 shows the various causes that have triggered lockdown conditions across all custodial facilities in Ontario. Lockdown types are categorized as being due to a staff shortage, a search, health care, administrative maintenance, inmate behaviour or a local investigation. In the eight years studied, the percentage of lockdowns due to staffing shortages has averaged about 82%. Note: data are incomplete for 2014 and 2021. Incidents are self-reported, and results should be interpreted with caution. Variations may be the result of incomplete reporting.

In 2014, 75% of lockdown conditions across all custodial facilities in Ontario were due to staffing shortages and 25% were due to searches. In 2015, 95.8% of lockdown conditions were due to staffing shortages, 3.2% were due to searches, 1.0% were due to administrative maintenance and 0.3% were due to inmate behaviour. In 2016, 88.6% of lockdown conditions were due to staffing shortages, 5.8% were due to searches, 4.4% were due to administrative maintenance, 1.1% were due to inmate behaviour and 0.6% were due to local investigations. In 2017, 81% of lockdowns were due to staffing shortages, 10.6% were due to searches, 8.2% were due to administrative maintenance, 1.4% were due to inmate behaviour and 1.0% were due to local investigations. In 2018, 64.9% of lockdowns were due to staffing shortages, 20.3% were due to searches, 12.4% were due to administrative maintenance, 2.7% were due to local investigations and 2.4% were due to inmate behaviour. In 2019, 82.1% of lockdowns were due to staffing shortages, 11.4% were due to searches, 6.5% were due to administrative maintenance, 0.7% were due to inmate behaviour and 0.2% were due to local investigations. In 2020, 82.4% of lockdowns were due to staffing shortages, 8.2% were due to searches, 6.8% were due to administrative maintenance, 1.8% were due to health care, 0.9% were due to inmate behaviour and 0.7% were due to local investigations. In 2021, 92.9% of lockdowns were due to staffing shortages, 3.1% were due to searches, 2.2% were due to administrative maintenance, 1.2% were due to health care, 0.6% were due to inmate behaviour and 0.4% were due to local investigations.