Protect, conserve, enhance and wisely use natural resources

The Growth Plan works in collaboration with the Greenbelt Plan and other provincial policies and plans to protect, conserve and wisely use natural resources. The policies in the Growth Plan call for the development of more compact and complete communities, which will use land more efficiently and reduce development pressures on important natural areas outside of settlement areas. Natural areas not only protect our natural heritage, but help to mitigate climate change removing and storing carbon. They also help to filter and store water improving water quality and reducing the impact of rain storm events.

Land consumption

The supporting indicator

Ratio of percentage change in size of settlement area to percentage change in planned population and employment.

Why it matters

The Growth Plan aims to reduce sprawl and support the wise use of land and resources by requiring intensification and a more compact urban form, and by establishing rigorous requirements for settlement area expansions. It is expected that municipalities will make sure that any expansions to settlement areas are as small as possible, to make the most efficient use of land. By tracking the size of any new settlement area expansions compared to the forecasted population increase, this indicator will help determine whether municipalities are planning to use land more efficiently.

How was it measured?

This indicator will be measured in the future only when, or if, there is a settlement area expansion beyond the settlement area boundaries set during the process of bringing official plans into conformity with the Growth Plan. At that time, the ministry will calculate the ratio of the percentage change in the size of settlement area, and the percentage change in planned population and employment. This ratio will then be calculated for each subsequent boundary expansion, if any. Over time, the indicator will show if there is a trend towards more efficient use of land in expanded areas.

Results

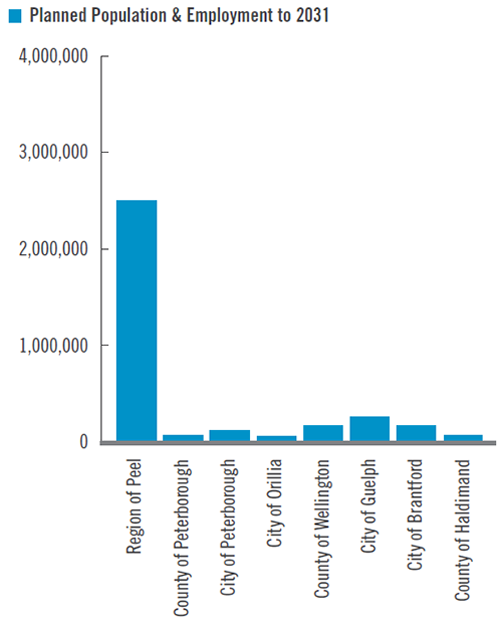

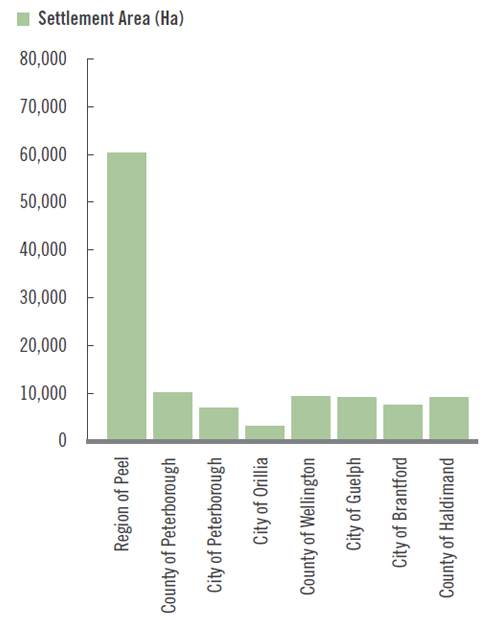

There are no results for the indicator at this time. The table shows the planned population and employment and the size of the settlement areas for the official plans that are now in effect and in conformity with the Growth Plan. This provides context against which future results can be compared.

Planned population and employment

Settlement area

*Official plans for the Regions of Durham, York, Halton, Waterloo and Niagara, the cities of Toronto, Hamilton, Kawartha Lakes and Barrie, and the counties of Northumberland, Simcoe, Dufferin and Brant are not yet in effect, either because they have not yet been approved or because they have been appealed in whole or in part to the Ontario Municipal Board. Information for these municipalities will become available as the settlement area designations and related population and employment forecasts are approved.

Considerations

The contextual information on planned population, employment and settlement area does not include official plans that have been adopted by council but not yet approved by the Province, or official plans that are before the Ontario Municipal Board. As the rest of the official plans are brought into conformity with the Growth Plan and are approved and in effect, the settlement area sizes and planned population and employment will be added to this contextual information.

Because this indicator can only be calculated after approval of settlement boundary expansions, it will take many years before a trend can be determined. Municipalities will also review and update their official plans at different times. Therefore, this indicator will not be updated for all municipalities across the region at the same time.

Watershed conditions

The supporting indicator

The percentage of hardened/impervious surfaces, natural cover, wetland features, and woodland features in watersheds in the Greater Golden Horseshoe.

Why it matters

Several policies in the Growth Plan encourage planning for water and wastewater services and stormwater management at a watershed scale to ensure that water quality and quantity are maintained, improved or conserved.

The amount of hardened surfaces and natural cover can affect water quality and quantity by impacting groundwater recharge and water storage, the amount and speed of surface runoff, erosion and flooding; and the amount of pollutants and nutrients entering water bodies. The amount of hardened surfaces and natural cover can also provide an indication of our ability to mitigate and adapt to climate change. Natural areas are particularly important in terms of their ability to absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Carbon sinks can also be created or engineered at the community scale to offset emissions from buildings or subdivisions.

The absence or presence of wetland and woodland features provides a more specific assessment of natural cover and impacts to water quality and quantity. Growth and development patterns can impact natural cover and increase hardened/impervious surfaces. Good growth planning and management can minimize the loss of natural cover and reduce the amount of new impervious surfaces.

How was it measured?

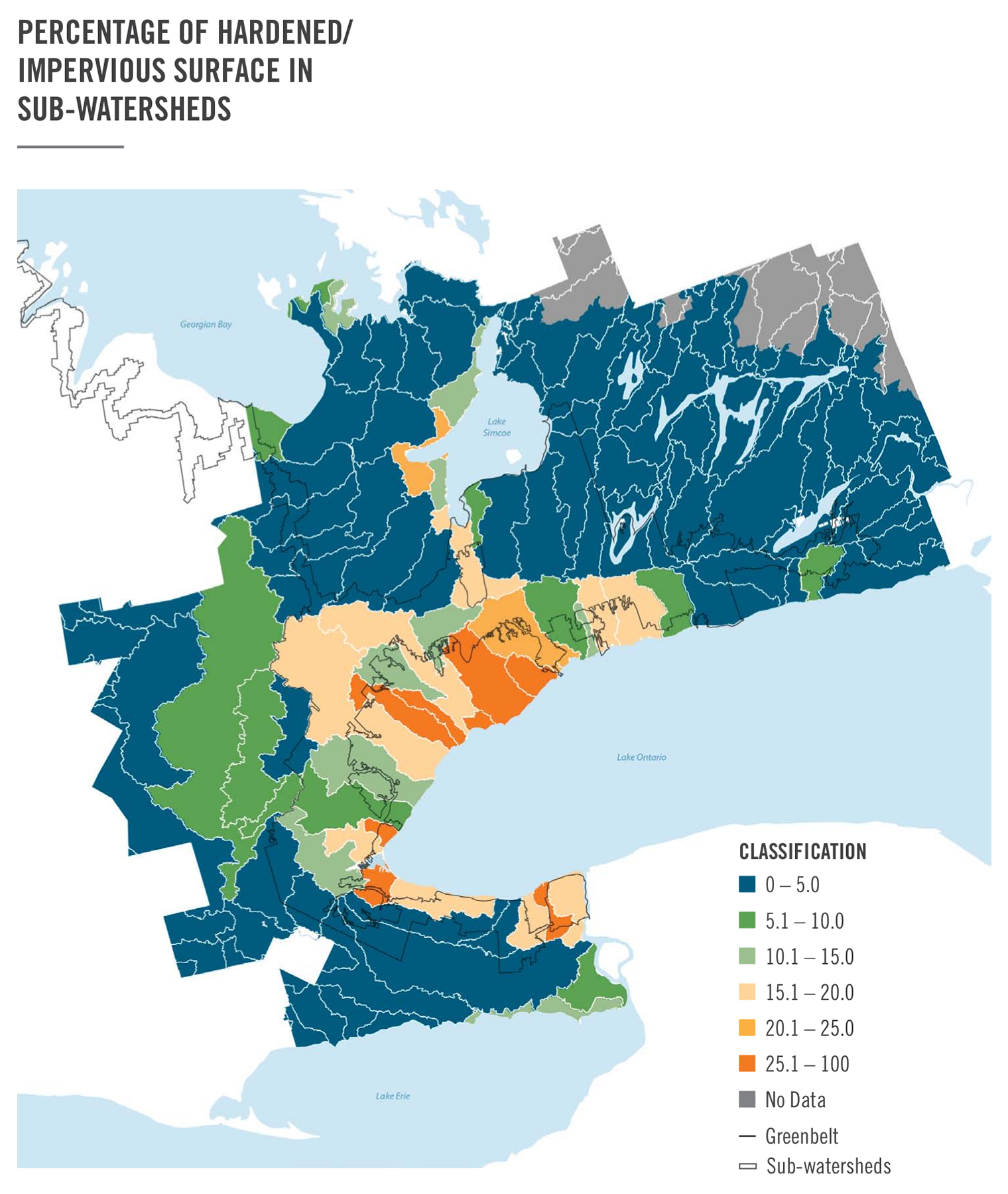

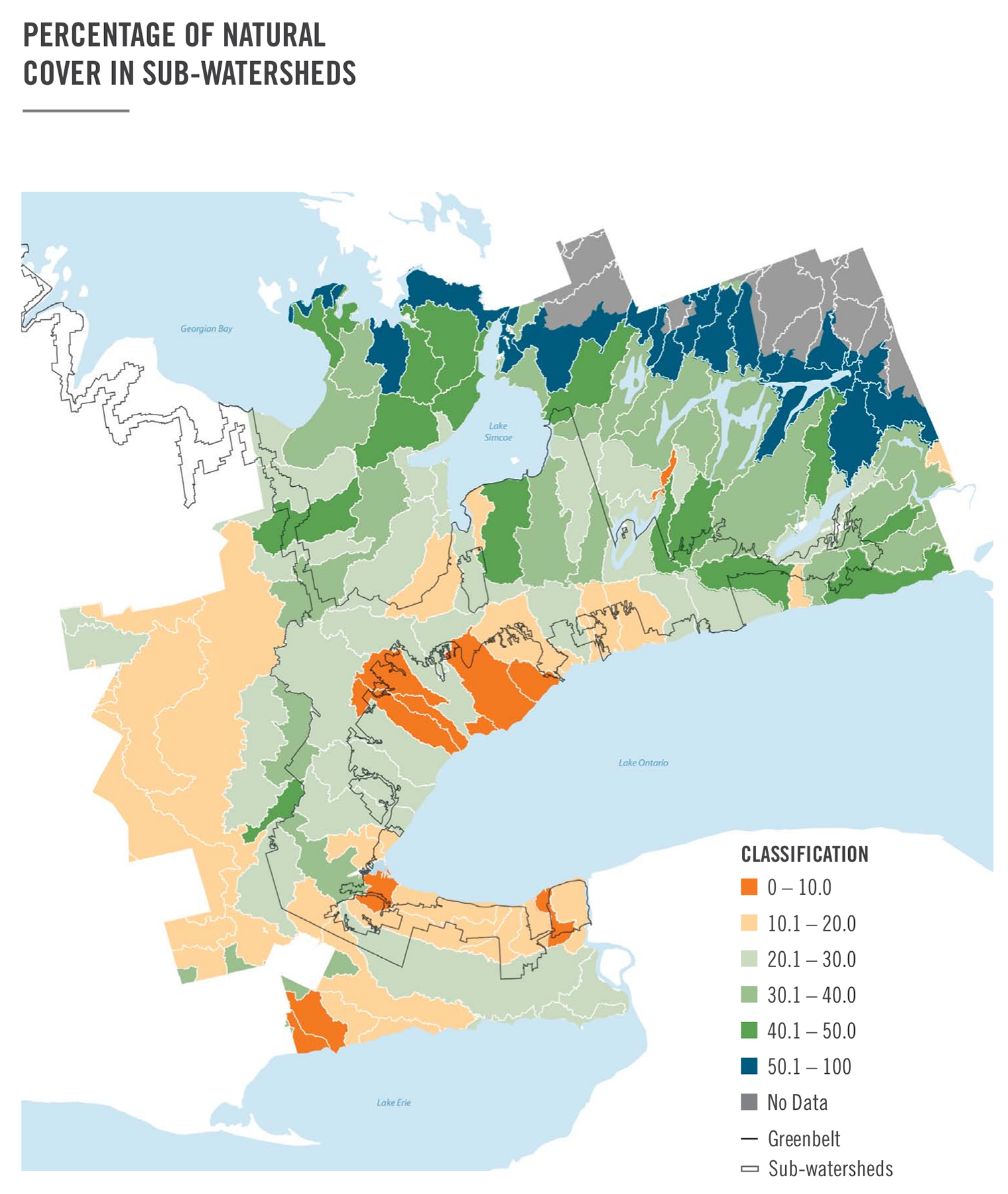

This indicator was developed using Southern Ontario Land Resource Information System (SOLRIS), Version 1.2, released in April 2008 and based on satellite imagery from 2000 to 2002. The SOLRIS data was broken down into 124 sub-watersheds across the Greater Golden Horseshoe and measured at a one-half-hectare grid resolution.

Hardened/impervious surfaces include paved surfaces and roofs that water cannot soak into. Natural cover consists of woodlands, wetlands, prairies, savannahs and sand barrens.

Results

The results provide baseline information against which future changes in watershed conditions can be assessed. The maps on page 40 provide some summary data on these results. Many watersheds have significant natural cover and small amounts of impervious surface; however in watersheds where that is not the case, management may be needed to mitigate impacts on water quality and quantity.

Summary results are presented in relation to minimum guidelines for watershed coverage outlined by Environment Canada. These guidelines provide a starting point to inform planning efforts to maintain the ecological and hydrological integrity in watersheds.

- 10 per cent or less hardened / impermeable surfaces for newly urbanizing watersheds

- 10 per cent or more wetland cover

- 30 per cent or more forest cover

There are no universally agreed goals for the amount of natural cover or hardened surface in a watershed; and planning authorities should use the guidelines to set coverage goals based on local circumstances.

| Sub-watershed | Number of Sub-watersheds | Percentage of Sub-watersheds |

|---|---|---|

| Sub-watersheds with less than 10% hardened/impervious surfaces | 95 | 77% |

| Sub-watersheds with more than 40% natural cover | 35 | 28% |

| Sub-watersheds with more than 10% wetland cover | 81 | 65% |

| Sub-watersheds with more than 30% woodland cover | 17 | 14% |

| Characteristic | Area (Ha) | Percentage of Entire Region |

|---|---|---|

| Hardened/impervious surfaces | 208,062 | 6.8% |

| Natural Cover | 908,855 | 29% |

| Wetland Cover | 441,834 | 14% |

| Woodland Cover | 466,933 | 15% |

Note: Other natural cover features such as prairies, savannahs and sand barrens, are not reported separately.

Considerations

The SOLRIS inventory is a compilation of data from various sources, including topographic maps, aerial photos and satellite imagery. Computer modelling, visual interpretation and field validation were used to create a seamless inventory for Southern Ontario.

No distinction was made between significant and non-significant wetlands and woodlands for the purposes of this indicator, since all woodlands and wetlands contribute to water quality and quantity. Agricultural lands were not included in these numbers.

View a larger version of this map (PNG).

View a larger version of this map (PNG).

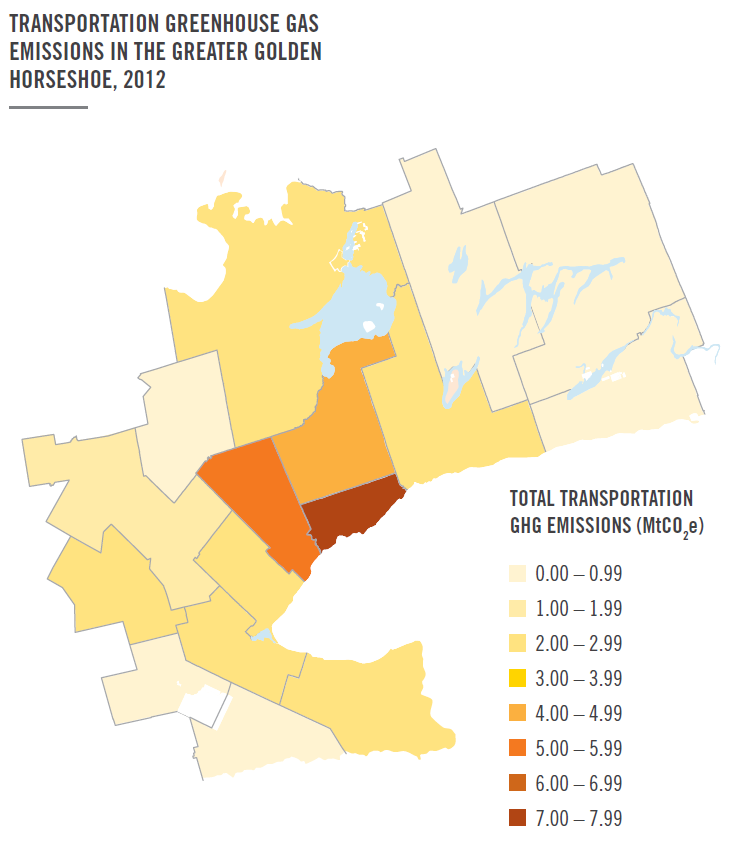

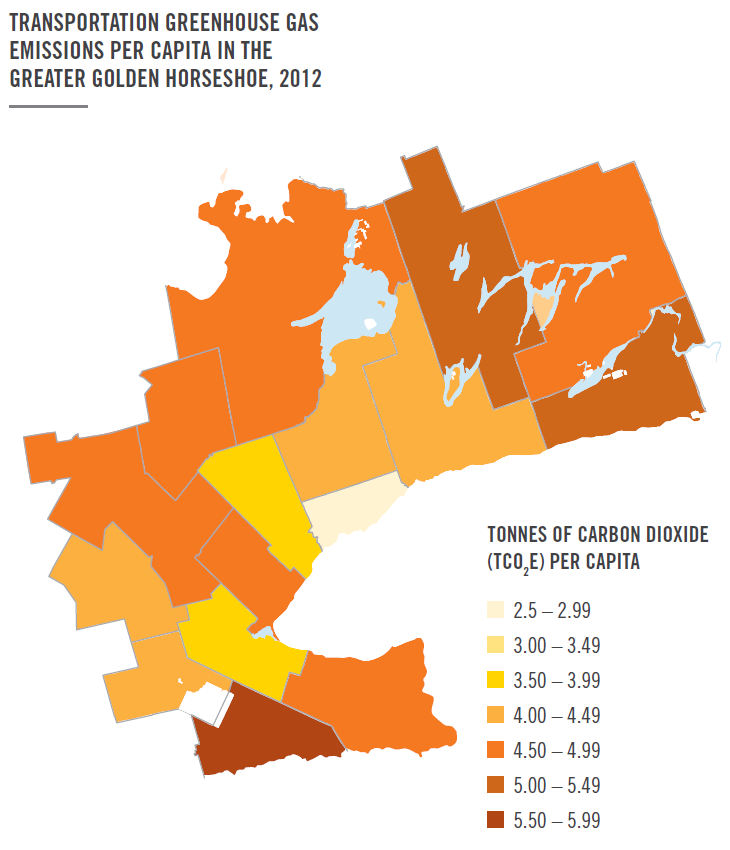

Transportation greenhouse gas emissions

The supporting indicator

Total and per capita greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (CO2 equivalent emissions in tonnes) estimated for the transportation sector by census division.

Why it matters

The implementation of Growth Plan policies on increasing density, improving transit, creating a more compact urban form, and improving energy efficiency, all have the potential to reduce GHG emissions in a municipality. Through good planning, municipalities can play a big role in curbing emissions.

This indicator provides a baseline to inform policy discussions about how planning can guide or support municipal efforts to reduce emissions.

Compact urban form and complete communities enable people to drive less, which can reduce congestion, and decrease per capita vehicle GHG emissions.

How was it measured?

Greenhouse gas emissions for private vehicles were calculated based on private transportation fuel consumption data for all of Ontario from Statistics Canada. The amount of fuel consumed per municipality was derived by dividing the number of private vehicles registered in the municipality by the number of private vehicles registered in the province, and then multiplying this ratio by the fuel consumption data for all of Ontario. For example, if a municipality had 15 per cent of the total provincial vehicle registrations, it was attributed 15 per cent of the fuel consumption. The GHG emissions were then projected by applying an emission factor to this quantity of fuel.

For public transportation, emissions were estimated based on fuel usage data obtained from the Canadian Urban Transit Association’s Ontario Urban Transit Factbook (2012).

Results

The results provide a baseline of information that will allow for comparison over time. It is expected that over time, more compact, transit supportive communities, and more fuel efficient vehicles, will result in an overall decrease in transportation GHG emissions. Three notable transportation patterns emerged in the baseline information:

- The City of Toronto was attributed the greatest amount of total transportation GHG emissions of any single municipality, at 7.5 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalents (MtCO2e), but had the lowest per-capita transportation GHG emissions, at 2.8 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalents (tCO2e) per capita.

- Upper- and single-tier municipalities in the remainder of the inner ring were attributed a combined total transportation GHG emissions of 16.8 MtCO2e, and an overall average

footnote 6 of 4.1 tCO2e per capita with a range of 3.8 to 4.6 tCO2e per capita. - Upper- and single-tier municipalities in the outer ring were attributed a combined total transportation GHG emissions of 10.1 MtCO2e, and had the highest per-capita transportation GHG emissions, at 4.7 tCO2e per capita with a range of 4.4 to 5.5 tCO2e per capita.

The maps show the total and per-capita GHG emissions from the transportation sector, by census division.

Considerations

The indicator assumes a standard rate of vehicle kilometres travelled and fuel consumed for each vehicle in the province. The indicator does not take into account driver behaviour (e.g., how far and how often people drive their car), the cost of driving or vehicle efficiency.

Lower per-capita vehicle ownership rates in some census divisions may, in part, reflect the fact that alternative forms of travel – by bike or transit for example – are more viable. In this way per-capita GHG emissions may be a proxy for urban form.

The approach to calculating this indicator has been used elsewhere and was found to provide results that are within 5 per cent of other accepted methods for estimating transportation GHG emissions in large urban areas.

However, due to limitations with this approach, other methods will continue to be considered in the future. There is a strong potential for the policies of the Growth Plan to influence transportation need and GHG emissions. Further refinements to the indicator could draw a better linkage between urban form and GHG emissions, e.g., to show directly how the integration of home location, work location, and access to public and alternative forms of transportation can reduce travel time, automobile usage and GHG emissions.

In the future, the province will seek to refine the current indicator by exploring access to point-of-sale fuel data and data on vehicle kilometres travelled (VKT). Access to this information would facilitate a more direct analysis of the relationship between urban density and transportation GHG emissions.

Footnotes

- footnote[6] Back to paragraph In this context, the overall average of the rest of the inner ring is calculated as the total emissions in this area divided by the total population in this area. The same calculation was used for the outer-ring per-capita estimates.