Part B: Observations and recommendations

Caregivers and caregiver supports In Ontario

Caregivers

Who are Ontario’s caregivers?

Caregivers provide unpaid care to their family, friends and neighbours of any age who have physical and/ or mental health care needs

Many caregivers attended our consultations. It was abundantly clear that caregivers are not a homogeneous group; rather, each one is unique with unique experiences. For example, I met:

- A young woman who quit work and cares full-time for her older mother.

- A middle-aged parent who provides specialized care for her autistic son.

- A middle-aged man who cares for his aging parents.

- An older man who cares for his wife with dementia.

- An older woman who supported her husband when he was alive and now helps a friend and neighbour who needs support to remain in her own home.

A caregiver is an individual as well as a member of a unit or dyad that includes the care recipient. Some caregivers live with those they care for whereas others routinely travel – sometimes long distances – to provide support. All caregivers are in constant contact with those they support. I was struck by the fact that the caregivers I met are deeply committed to fulfilling their caregiving responsibilities, however stressful and challenging they may be. Some do so willingly and consider it a part of life; whereas others are compelled by family expectations or an inability to find what they consider to be sufficient supports.

A number of caregivers pointed out that their relationship is characterized by an unequal give-and-take. Research has shown that caregiving has major impacts on the lives of caregivers including significant negative impacts on their emotional well-being (Lin et al. 2016), increased levels of stress and distress, financial hardship, an inability to concentrate at work, job instability (such as leaving jobs voluntarily or involuntarily), and so on. (The Change Foundation 2016)

I listened to caregivers talk about the high levels of stress they feel. A number of them commented that they cannot quit their roles – and do not want to quit – even though they may feel frustrated, tired, discouraged, resentful, and even afraid of what the future will bring when the person they care for ages, gets sicker, has a health crisis or passes on. Everyone I listened to agreed that caregivers need support to be able to continue caring.

What contribution do caregivers make?

The Change Foundation estimated that 3.3 million Ontarians – or 29 per cent of the provincial population – provide support and care to a chronically ill, disabled, or aging family member, friend or neighbour (2016)

It has been further estimated that it would cost upwards of $26 billion annually to replace the work of Canadians caring for seniors with paid equivalent care (Hollander et al. 2009). This cost would be higher when caring for family, friends and neighbours of all ages.

I believe that caregivers’ contributions and their value will continue to increase substantially in the future. Ontarians have benefitted from many significant trends such as higher life expectancies, technological advances that save and prolong lives, effective management of chronic illnesses, and shifts from inpatient to outpatient care and from hospital to home and community-based care, to name a few.

Although these trends are highly positive, they have placed higher expectations on caregivers to support their loved ones who now survive, live longer, experience age-related illnesses, are technology dependent, need ongoing therapies, need help getting to and from medical appointments and procedures, and need help functioning on a daily basis. These trends have also placed higher expectations on children and youth who may be helping to care for their siblings, parents and grandparents.

Societal trends have also exacerbated the pressure on caregivers. The shift from larger extended families to smaller families, increased mobility where adult children may live further from their parents, and greater participation of women in the paid workforce mean that responsibility for family caregiving may fall on fewer adult children who may live at a distance and have workplace and other family obligations.

It is well recognized that our tax-funded health care system and its paid providers make a highly valued and substantial contribution to meeting the care needs of Ontarians. What is less well recognized, valued and, indeed, included in economic equations is the significant contribution that unpaid caregivers make. They augment our taxpayer-funded services, are an intrinsic part of Ontario’s health care system, and contribute significantly to the health and well-being of its citizens.

Caregiver supports in Ontario

Many organizations provide highly valued services in focused areas of expertise and with various sources of funding

The consultations highlighted the fact that many organizations provide highly valued caregiver supports in Ontario. These organizations play a critical role and have a strong track record of supporting care recipients and caregivers either directly or indirectly. In the latter instance, for example, organizations may provide services such as respite care which helps support the caregiver while attending to the care recipient’s needs.

These organizations - and the services they provide - vary widely in terms of focus and funding.

The majority of organizations focus on selected areas of expertise such as:

- A disease, condition or issue (e.g., cancer, heart and stroke, Alzheimer’s, multiple sclerosis, schizophrenia, bereaved families, etc.).

- Particular ages (e.g., infants, children, youth, older persons, etc.).

- Type of service (e.g., healthy living, helping people stay in their homes, etc.).

The focus on selected areas of expertise can be very challenging for caregivers. During the consultations, one caregiver noted that their needs did not fall cleanly into any existing disease or age-oriented organizations:

“I just care for my 26 year old son who cannot be left alone.”

An additional challenge is that caregivers may not find supports in certain areas and may become confused about what they can expect and depend upon. One caregiver commented that she was supported very well when her mother was diagnosed with dementia; however, when her father was debilitated with another illness, she found little to no support.

There are commonalities among organizations with a specific focus. Typically they provide caregiver support services such as information and education. Some also help caregivers navigate services, and may engage in research and advocacy on behalf of caregivers.

Funding for caregiver supports varies widely. Organizations and services may be:

- Publicly-funded such as programs through the LHINs, Community Care Access Centres (CCACs), hospitals and primary care

footnote 3 . - Privately-funded by for-profit or not-for-profit companies such as organizations that offer supplemental home care or home support.

- Funded through charitable donations and foundations.

The funding source tends to influence the caregiver supports that are developed and where they are locally available. For example, a LHIN’s priorities will directly influence whether it allocates funds for caregiver supports. As well, for-profit organizations may prefer to develop selected services that have defendable business cases, whereas philanthropic funding may focus on supports that have a personal or emotional connection to donors.

There is inequitable and ineffective access to caregiver supports

Ontario has some superb caregiver support initiatives. Regretfully, they tend to exist in pockets or focused areas that may not meet the needs of all caregivers. The result is inequitable and ineffective access to appropriate caregiver supports across the province. Typically, caregivers discover these gaps when they try to find needed supports.

Examples from the consultations include:

- One LHIN participant described a program of caregiver education that they had recently purchased and how positively it was being received, yet participants from other LHINs were either unaware of the program or did not have any plans to adopt such a program.

- A representative of a disease-focused organization believed that their regional model worked very well, with many caregivers in the consultations agreeing; however, other caregivers stated that this support was not available in remote areas where they lived.

- A caregiver commented that the services for her husband were terrific in one area but when they moved to another LHIN, he could not access the same supports or level of support. The expectations and demands on the wife to provide care increased.

Generally, I observed that organizations that focused on diseases or were in selected areas of the province appeared to think they were doing an effective job of meeting caregiver needs. In comparison, caregivers were more likely to identify gaps and limitations in the supports available. For me, this highlighted the importance of validating the caregiver’s experience and taking the caregiver’s perspective.

Caregiver supports in other jurisdictions

It was very useful to examine the experiences and models of other jurisdictions that have more formalized approaches to caregiver support. These included:

- Nova Scotia

- Alberta

- Sweden

- United Kingdom

Additional information on these jurisdictions can be found in Appendix D.

A made-in-Ontario approach to supporting caregivers

Introduction

I believe that an appropriate made-in-Ontario approach to supporting caregivers has to articulate clearly what caregivers need. One of my primary focuses was to obtain consensus on what this would be. The review of background documents helped to identify a long list of potential caregiver supports. These documents – along with an assessment of caregiver organizations in other jurisdictions – were also used to identify potential options for a structure.

All this information was presented to those I consulted with for discussion, debate and improvement. This grassroots input was invaluable for guiding and shaping my final advice and recommendations on caregiver supports and a structure to provide these supports.

Caregiver supports

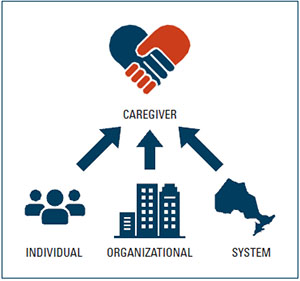

There is a tendency to assume that individual level supports are sufficient to sustain effective caregiving. I believe that effective caregiver support needs to include initiatives at the individual, organizational and system levels. There was very strong agreement on these three levels of support throughout our consultations, along with wide-spread agreement on the specific supports needed at each of these levels.

Level of caregiver support

Individual level supports

The consultations highlighted the fact that caregivers struggle trying to access information and supports for various reasons. They:

- Do not know where they are.

- Do not know how to access them.

- Find supports that are too specialized and unable to meet their needs.

- Cannot find general supports relevant to all caregivers.

In addition, caregivers reported having gaps in knowledge and needing information on how to fulfill their caregiving role. A number of caregivers stressed the importance of information that is relevant to the phase of caregiving they are in. The caregiver’s role evolves over time in relation to the changing needs of the care recipient.

Caregiver supports at the individual level need to include the following two initiatives:

1. Establish one access point

Individual caregivers need one access point to connect to regardless of where they live, the resources they have, or any communication challenges they may face. A number of stakeholders noted that having a one-number-to-call when they faced critical caregiving challenges and needed immediate connection would go a long way towards supporting them and keeping the care recipient at home longer.

One access point should have the capacity to:

- Provide consistent information on caregiving and the services and supports that are available to the caregiver

footnote 4 . - Advise caregivers on the most appropriate services to meet their needs, with sufficient details on the type of service, who provides it, how it can be accessed, and cost.

- Link caregivers to the services and organizations that would meet their needs. This active navigation could include linking caregivers to specific services or programs (such as being a caregiver; giving medications; moving someone without hurting them and yourself; when to call for help or go to the hospital; the trajectory of a disease, illness or impairment; and so on).

There was overwhelming support for a “warm connection to a person and a warm handoff to another person.” There was also widespread agreement that one access point should be equitable for everyone across the province, and that it should be sensitive to the unique needs of caregivers of various cultures, orientations, languages, ages and other factors (e.g., Indigenous Peoples (First Nation, Métis, Inuit), French Language, LGBQ, and other groups).

2. Offer education and support programs

These programs should focus on meeting the general needs of all caregivers. Examples from the consultations include but are not limited to how to juggle multiple priorities when caregiving, re-entering the workforce after caregiving, and coping with no longer being a caregiver.

Organizational level supports

The consultations highlighted the fact that although Ontario has many valuable caregiver supports, organizations have different foci and reflect pockets of excellence in selected areas. This leads to variable access depending on where caregivers live and what problems they face. It was also suggested in the consultations that many organizations would benefit from knowing what each other is doing while respecting their competitive advantages from a philanthropic perspective.

There was widespread agreement that caregiver supports at the organizational level need to include the following two initiatives:

1. Address gaps in caregiver services and supports within and between LHINs

This would involve identifying gaps and advising on opportunities to address these gaps, standardize services, expand excellent programs, and improve equitable access to caregiver supports.

2. Facilitate caregiver organizations to collaborate on addressing gaps and maximizing their impact

This would involve inviting caregiver organizations to come together to:

- Identify and close service gaps.

- Share ideas and successful approaches.

- Make better use of their collective resources by minimizing duplication.

- Expand excellent programs.

- Improve equitable access to caregiver supports.

System level supports

The consultations highlighted the fact that there are broad caregiver support issues that cannot be effectively addressed at an individual or organizational level. These include wider public issues as well as those that involve multiple provincial ministries – such as health, community and social services, education, housing and transportation – and involve various levels of government such as provincial, municipal and federal.

There was widespread agreement that caregiver supports at the system level need to include the following four initiatives:

1. Conduct public education and awareness programs

These programs should focus on the value, importance and challenges of caregiving. Some key messages that were suggested include: the impact of caregiving on caregivers, and the rights of caregivers to have healthy lives themselves.

2. Increase knowledge among health care and other service providers about the role, value and active engagement of caregivers

Caregivers in the consultations gave examples of being with their families, friends or neighbours, and being ignored or overlooked by service providers (such as physicians, nurses, emergency medical services, police, and others). Typically, caregivers can provide valuable information and assistance in these situations (e.g., calming down an overly anxious child or parent, communicating information that may be hard to understand).

It was suggested that in the short term, organizations – such as hospitals, clinics, emergency service, police – could train their staff. In the longer term, this type of training could be included in the curriculum of education programs.

3. Advise on improved caregiver support policies and legislation

This advice may address as well as align policies and legislation at the municipal, provincial and federal levels. For example, caregiver needs must be considered in provincial health system reform such as primary care. Another example is education reform where individuals who leave the workforce to be full-time caregivers could receive educational credits for the skills they have developed.

4. Advise on and participate in caregiver research

This research could focus on caregivers, their needs, and caregiver support best practices. There is increasing interest in studying caregiving from many perspectives. Caregiver research – including design, conduct and implementation – should increase our understanding of, and improve, the caregiving experience. There is a need to avoid research or survey fatigue among caregivers and care recipients.

A structure to provide supports

There was widespread agreement throughout the consultations that existing organizations play a critical role supporting care recipients and caregivers. These include organizations focused on particular diseases, home and community care provider organizations, patient and caregiver associations, and taxpayer-funded health care services. Everyone agreed that this important support needs to continue.

There also appeared to be agreement that currently Ontario has no organization or entity that:

- Focuses solely on caregivers and their multiple diverse needs;

- Reflects the broad culture of caregiving as opposed to caregiving within a focused area(s); and

- Can deliver and coordinate the full-range of caregiver supports set out in Recommendation 1.

In the consultations, caregivers supported creating an organization dedicated to meeting their broad needs. Representatives of existing organizations were generally supportive and could see the value of a caregiver organization. They expressed some concerns about the ability of an organization to catch up to existing systems of support, and wondered where such an organization would fit in the current system. Existing organizations also cautioned against duplicating caregiver services that are already available.

There was general agreement on the underlying principles to guide a caregiver organization; however, opinions varied widely on the best structure to deliver and coordinate caregiver supports.

Underlying principles for a caregiver organization

The following principles emerged through the consultation process. A made-in-Ontario caregiver support organization must:

- Partner with caregivers in designing, creating and governing the organization while avoiding doing this work “on the backs of caregivers.”

- Add value for caregivers by improving their caregiving experiences.

- Focus on general supports that all caregivers may need regardless of the disease, condition and/or age of the care recipient.

- Be able to cross government ministries to support the multiple needs of caregivers – such as education, transportation, housing, employment, social services – as care recipients transition across different levels of care.

- Avoid taking on the responsibilities of other organizations or government (e.g., mediating home care services provided through the LHINs; funding individual services, etc.).

- Partner with existing provincial, regional and local organizations, programs and services to maximize supports, minimize duplication, and expand what currently exists more broadly across the province.

- Recognize and provide caregiver supports to French Language caregivers in French.

- Ensure that the organization’s structure and all its activities support diversity, equity, inclusivity and cultural competence (i.e., the ability to understand, communicate and effectively interact with people across cultures). This includes being sensitive and responsive to the unique caregiver support needs of Ontario’s population including but not limited to:

- Indigenous Peoples (First Nation, Inuit, Métis). The unique needs of Indigenous Peoples were not explored in depth. Further engagement to co-design and co-develop appropriate caregiver supports is required.

- LGBQ Communities. The consultations identified unique caregiving issues, including caregivers and care recipients who may hide their gender identities to avoid mistreatment, harassment, and refusal of health services and support.

- Be cost responsible and maximize system effectiveness by leveraging current systems and databases that are appropriate and relevant.

Options for a caregiver support organization

Based on previous reports, studies and consultations on the needs of caregivers – as well as additional consultations with over 200 individuals – I believe that caregivers would benefit from a formalized provincial approach to caregiver support. I considered a number of options all of which were suggested in one form or another through the consultations.

One option was to create a caregiver support organization as a provincial government agency. An Ontario agency would be established by and accountable to government but not actually be part of a government ministry. An agency would have the authority and responsibility to perform a public function or service. Generally, government appoints the individuals who sit on the agency or its governing body. Although this option would give the caregiver organization a high provincial profile, it may be seen as being too closely aligned to government to reflect the unique culture of caregiving. As well, a provincial agency may not be perceived as an objective voice of caregivers when it comes to addressing issues that include multiple provincial ministries (such as health, community and social services, education, housing and transportation) and various levels of government (such as provincial, municipal and federal). For these reasons, this option was regarded as unacceptable.

A second option was to make a caregiver support organization a department or program within the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Caregiver support would become a government service which would make it difficult to involve caregivers in governance other than as advisers. Ultimately, government would have the authority to make decisions about the service. Other organizations may perceive the service as getting preferential treatment for funding since it is within government. It would also be difficult for the service to reflect the unique culture of caregiving. Furthermore, since the service would be within the health ministry, it would be difficult to address issues that cross multiple ministries and various levels of government. This option was not accepted.

A third option was to create a caregiver support organization run by the collective group of 14 LHINs. Individual LHINs are knowledgeable about their local populations and local health and community services. They would be able to use this knowledge to provide individual level supports. However, since LHINs are now responsible for providing home care services, caregivers may not regard a LHIN-run organization as an objective voice for caregivers. Although there is merit to LHINs bringing a regional perspective, it could be challenging for LHINs to address organizational and system level supports. Finally, if the caregiver support organization is to succeed, an unrelenting focus on development and implementation is needed now. At this time, LHINs are undergoing significant organizational changes and, by necessity, must focus their efforts on successfully executing these changes. This option was not accepted.

A fourth option – and one which I regard as doable, practical and most appropriate – is to establish a stand- alone caregiver support organization. Such an organization would be able to focus on the full range of individual, organizational and system level supports recommended earlier (Recommendation 1). In addition, it would be perceived as arms-length from government, involve caregivers in governance, embrace a regional caregiver support model under a provincial umbrella, be sensitive and responsive to the unique caregiver support needs of Ontario’s population, and be cost responsible.

The characteristics of this option – which needs to be continuously evaluated and modified, as required with the evolving health care system – should include the following elements:

Governance leadership

- Governance provided by a volunteer Board of Directors who have the appropriate skills and expertise. The Board would be representative of Ontario’s diverse population, and seek to balance experience in areas such as caregiving, policy, finance, legal, business and other areas.

Management leadership

- A staff secretariat at a central location and at regional locations strengthened by local volunteer networks.

Location

- Central and regional locations. Ideally, these regional locations would be aligned with and co-located within each of the 14 LHINs; however, it would be important to have an arms-length relationship from the LHINs to avoid confusion and any disputes related to home care support.

Staffing

- Staffing at the central location would include a Chief Executive Officer (CEO), administrative support, and selected central staff to oversee key functions (e.g., one-number-to-call, education programs, information systems, marketing and communications, and other functions).

- Staffing at the regional locations would include at least one local area caregiver support lead in each region, augmented by a team of volunteers.

Corporate status

- The organization would have non-profit charitable status to enable research and other grant opportunities. The organization would not compete in fundraising but could receive donations from grateful participants or foundations.

Funding

- There would be multi-year government funding linked to goals and deliverables. Back office functions could be provided by another organization to minimize overhead costs.

Accountability

- All staff would be accountable to the CEO.

- Organizational accountability would be to the Minister of Health and Long-Term Care or their designate.

- Accountability for performance would include performance indicators that measure both process and outcomes at the individual, organizational and system levels. These could include but not be limited to: caregiver satisfaction with supports; successful links between caregivers and the supports they need (i.e., removal of silos); satisfaction with information and education received; organizational collaborations; etc.

Regional / local activities

- Staff would provide management and operational support at the central location with community outreach and engagement at regional locations.

- There would be ongoing two-way communications between the central office and regional locations to identify and address common issues, gaps and duplications, standardize programs, and ensure that programs are delivered and evaluated locally. Issues unique to some regions would benefit from discussions with, and the support of, the other regions.

- Local program delivery would include strategies related to: self-help; caregiver to caregiver outreach; engagement of local teams and individuals (e.g., pharmacists, physiotherapists, lifestyle coaches; local spiritual/religious leaders; etc.); coaching; compassionate community initiatives; virtual support groups; and active partnering with local organizations that currently deliver programs.

- Staff would ensure that French language caregivers are served in French.

- Staff would engage Indigenous Peoples to co-design and co-develop appropriate supports to meet their unique caregiving philosophy.

- Staff would work with members of the LGBQ communities to further understand and develop appropriate caregiver supports.

The following vision and mandate for the organization are proposed for consideration and further development:

Vision: That all caregivers feel supported and valued.

Mandate: To use information, support and respect to enhance the caregiving experience in Ontario.

I believe it will be important to respect the critical role played by existing organizations that have a strong track record supporting care recipients and caregivers, such as those that focus on particular diseases, home and community care provider organizations, patient and caregiver associations, and the other parts of the health care system. Their input has been invaluable and, going forward, we need to draw on their experience and expertise, and leave room for their continued support to caregivers.

See Appendix E for additional details of the recommended model.

A commitment to implement

I believe that a strong commitment to implement is needed to ensure success. Given that it will take time and effort to plan, confirm and/or strengthen the proposed characteristics of the model, and begin to develop the organization, the ministry should consider appointing an Implementation Lead in the short term to begin this important work.

In closing, a great deal will be expected of a made-in-Ontario caregiver organization. It will be essential to pace the implementation which means that some initiatives will be addressed sooner than others. I believe that caregiver engagement, genuine communication at multiple levels, ongoing feedback and patience will help this evolving organization deliver what Ontarians need.

Footnotes

- footnote[1] Back to paragraph Other terms used to describe individuals who provide unpaid care to their family, friends and neighbours include carers and informal caregivers.

- footnote[2] Back to paragraph The Change Foundation analyzed Statistics Canada’s 2012 General Social Survey Data specific to Ontario.

- footnote[3] Back to paragraph The mandate of the LHINs – as the single point of accountability for integrated home and community care – is being expanded to include home care services from the CCACs. The transfer from the CCACs to the LHINs was completed in June 2017.

- footnote[4] Back to paragraph This could include general information such as the availability of financial programs and relief programs and how to access them.